CHAPTER 8

Isaiah 40–55

“We all, like sheep, have gone astray, each of us has turned to his own way; and Yahweh has laid on him the iniquity of us all.”

(Isa. 53:6)

CHARACTERISTICS OF ISAIAH 40–66

Although we will discuss Isaiah 40–55 and Isaiah 56–66 in separate chapters, the two sections are related and need to be introduced briefly as a unit. As discussed in the overview of Isaiah in chapter 6, the second half of Isaiah (chapters 40–66) is a bit different from the first half. Here are some of the characteristics of Isaiah 40–66:

1. The primary people whom Isaiah addresses are those in the exile.

2. No specific historical events are mentioned, and there are no words addressed to specific kings or individuals (like Ahaz, Hezekiah, Sennacherib, etc., as in Isaiah 1–39).

3. “Fear not!” is a major theme, often accompanied with words of comfort.

4. Israel is still being charged with covenant violation, as in Isaiah 1–39.

5. Salvation is promised (as in Isaiah 1–39) both in the near sense and in the far sense, often expressed in terms of a “new exodus,” one that even includes Gentiles.

6. Yahweh refers to his people in personal, intimate terms.

7. Yahweh is praised for his many awesome attributes (holiness, sovereignty, power, control of history, etc.).

8. As in Isaiah 1–39, there are strong polemics against the idols and the nations.

9. Cyrus (king of Persia) is presented as Yahweh’s instrument for judgment (on Babylon) and for deliverance (for Israel).

10. Deliverance focuses on the role of the Servant, presented in four Servant Songs (42:1–9; 49:1–13; 50:4–11; 52:13–53:12). Uniquely, the coming Servant will bring salvation through suffering.1

The Great Scroll of Isaiah (1QIsa9), one of the best preserved of the Dead Sea Scrolls, is almost totally intact.

NT Connection

All four gospels cite Isaiah 40:3–5 (“the voice of one calling in the desert”), identifying John the Baptist as the “voice in the desert” and identifying Jesus as the Coming One prophesied in this passage (Matt. 3:3; Mark 1:3; Luke 3:4–6; John 1:23).

OVERVIEW OF ISAIAH 40–55

While Isaiah 1–39 focuses on the first two points of the prophetic message (broken covenant and judgment), Isaiah 40–55 centers on the third point—future hope and restoration for Israel and the nations. At the heart of this section is Yahweh’s saving grace.

ISAIAH 40—BE COMFORTED AND SOAR LIKE AN EAGLE

Just as Isaiah 1 introduces 1–39, so Isaiah 40 introduces 40–66. Furthermore, these two introductory chapters are related through the use of many similar words, themes, and images. Terminology from Isaiah 1 that refers to sin and judgment reappear in Isaiah 40, but in the context of comfort and restoration. In effect, while in chapter 1 the punishments prophesied have already taken place, chapter 40 shifts the focus toward the glorious restoration.

In essence, Isaiah 40 serves not only as introduction but also as a summary of many of the major themes of 40–66. In 40:1–2 comfort is proclaimed to Jerusalem, and an end to her punishment is announced. Next the prophet orders that preparations be made, for the glory of Yahweh is coming and will be revealed to all (40:3–5). This is in accordance with the word of Yahweh, which stands firm forever, unlike frail humanity, which perishes quickly (40:6–8). After the preparation and in accordance with his word, sovereign Yahweh comes, combining strong, victorious power with kind, gentle compassion (40:9–11). This is beyond our understanding because mere mortals cannot comprehend Yahweh or his plans (40:12–14). All of the nations that have caused so much consternation and suffering for Yahweh’s people are nothing before him; indeed, they are like drops in a bucket (40:15–17). Yahweh, on the other hand, is everything, the supreme all-powerful being. The idols cannot compare to him, for they are like the nations—nothing (40:18–26). Therefore, and in conclusion, Yahweh’s people should not despair, but rather soar like eagles (40:27–31).

ISAIAH 41:1–44:23—FEAR NOT, FOR I AM WITH YOU

Isaiah 41 continues the theme of Yahweh’s power over the nations and the idols. Yahweh declares that he is the one who will raise up Cyrus to subdue many of the nations. Although Cyrus is not specifically named yet, later passages make clear that Isaiah is referring to Cyrus in 41:2–3 and in 41:25. Likewise, this chapter includes comforting words for the Israelites (41:8–10), words that will be repeated frequently in the chapters to come. Yahweh reminds them that they are very special (“my servant, whom I have chosen, seed of Abraham”). In Isaiah 41:10 Yahweh exhorts his people not to fear, because he is with them. This is a statement of Yahweh’s powerful and empowering presence, a major theme in the prophets—and, indeed, throughout the entire Old Testament.

As mentioned above, Isaiah 40–55 contains four passages that focus on a very unique and special Servant of Yahweh (42:1–7; 49:1–6; 50:4–10; 52:13–53:12). These passages are filled with messianic references, and the New Testament frequently connects Jesus to these Servant Songs. Isaiah 42:1–7, the first Servant Song, stresses that this coming Servant will have the Spirit of Yahweh and will establish justice on the earth for all the nations (note the repetition of justice in 42:1, 3, and 4). Uniquely, though, and in contrast to most conquerors, the Servant will be quiet and meek (42:2–3). Yahweh reminds the audience that he is the creator of all life (42:5) and also the one who proclaims what is going to happen before it happens (42:9). Yahweh tells the Servant that he has called him in righteousness and will make him a “covenant for the people and a light for the Gentiles [or nations], to open eyes that are blind, to free captives from prison and to release from the dungeon those who sit in darkness” (42:6–7). Thus the Servant is presented as one who will be a mediator of a (new?) covenant as well as the one who delivers the nations and opens their eyes to the truth.

The New Exodus

The exodus is without doubt one of the most significant theological events in the Old Testament. Yahweh miraculously and powerfully delivers his people from slavery in Egypt. He leads them through the Red Sea, across the desert, through the Jordan River, and victoriously into the Promised Land, defeating all nations who dared to oppose them. In the Old Testament the exodus event becomes the paradigm or model of what salvation is all about. In a sense, one could say that the exodus is to the Old Testament as the cross is to the New Testament.

The prophets draw heavily from the events of the exodus, frequently using the images associated with that great deliverance. Occasionally, the prophets will describe the coming judgment in terms of an exodus reversal, that is, a reversal of their great salvation history (e.g., Jeremiah 41–43). But most frequently, the prophets use the imagery of the exodus to describe the coming messianic age. When the prophets proclaim the coming glorious restoration, they will often describe it poetically and figuratively in terms of a great New Exodus. Isaiah, in particular, speaks colorfully of a coming time when Yahweh will once again gather his shattered people, deliver them from their oppressors, and lead them into the Promised Land. In this New Exodus, Yahweh will dry up waters and rivers to allow his people to cross safely (Isa. 11:15; 19:5; 43:2), just as he had led Israel through the Red Sea and the Jordan River in the first exodus.

A striking development in the prophets’ exodus imagery, however, is that they proclaim quite clearly that the New Exodus will be even more glorious than the original exodus. For example, in the original exodus, Yahweh gathered up the Hebrew slaves from Egypt, but in the New Exodus, he now includes the lame, the blind, and other weak people (Mic. 4:6–7; Isa. 40:11; 42:16; Jer. 31:8). In the New Exodus these regathered people will come not only from Egypt but from all nations, north, south, east, and west (Isa. 43:5–6). In addition, the New Exodus will not be limited to the deliverance of Israel, but it will extend to the nations as well, including even Israel’s old adversary, Egypt herself (Isa. 11:10–16; 19:19–25). The New Testament continues this theme, identifying Jesus as the one who brings about the New Exodus prophesied by the Old Testament prophets.

NT Connection: Jesus Quietly Withdraws

In Matthew 12:15–16 Jesus withdraws from the crowd, warning those who followed him and have been healed to be quiet about who he is. Matthew cites this quiet withdrawal of Jesus as a fulfillment of Isaiah 42:1–4 (Matt. 12:17–21).

Isaiah 43:1–7 once again encourages the people in exile to “fear not!” In this passage Yahweh stresses the close, intimate relationship he has with his people. Because he has created them, redeemed them, and called them by name, they belong to him (43:1). He also refers to them as sons and daughters and tells them how precious they are to him and how he loves them (43:4–6). In 43:5 Yahweh repeats, “Fear not, for I am with you,” comforting them with his powerful presence.

In Isaiah 43:14–21 Yahweh promises deliverance from the Babylonians. In 43:16–17 he alludes to the exodus event, which was perhaps the central salvation event in Israel’s history so far. Yet Yahweh states in 43:18–19 that the “new thing” he is doing (the deliverance and restoration brought about by the Servant and proclaimed throughout Isaiah) will overshadow the “former things” (even the exodus!).

Isaiah 44:1–6 repeats again, “Do not be afraid!” Yahweh promises a time of refreshing that culminates in his pouring out his Spirit on the people of Israel (44:3). As the prophets look forward to the new, better reestablished relationship with Yahweh, one of the spectacular new features mentioned by Isaiah, Joel, and Ezekiel is the gift of Yahweh’s Spirit to people. Joel 2:28–29 and Ezekiel 36:26–27 expound on this phenomenon in more detail than Isaiah does, but all three passages point to the future outpouring of Yahweh’s Spirit that was fulfilled in the New Testament at Pentecost (Acts 2).

Isaiah 44:6–20 is a polemic against the idols. The prophet’s tone is sarcastic, and his diatribe is filled with ironic humor. A man cuts down a tree. Half of the tree he puts in the fire to warm himself, and half of the tree he uses to fashion an idol to which he bows down to worship (44:14–17). Isaiah proclaims that to worship and to trust in such idols is ridiculous.

ISAIAH 44:24–48:22—CYRUS

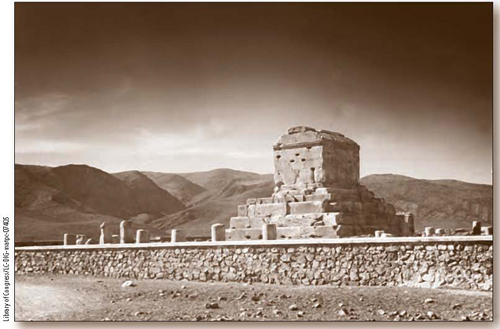

As discussed in chapter 2, Cyrus came to the throne of Persia in 559 BC, and in 539 BC he conquered the Babylonian Empire, thus controlling the Jewish exiles that were in Babylon. In 538 BC he issued a decree that allowed the Jewish exiles to return home.

Earlier in Isaiah, the prophet referred to Cyrus simply as “the one from the north” or “the one from the east” (the Persian Empire stretched far enough across Mesopotamia that it was both to the east and to the north). Several times Isaiah refers to Cyrus explicitly by name (44:28; 45:1, 13) and a few times implicitly and unnamed (46:11; 48:14–15). As a demonstration of his ability to control history, predict the future, and bring events into being that had been foretold, Yahweh raises up Cyrus to judge Babylon. Yahweh thus stresses his incomparability. The idol gods, even those of Babylon, cannot do this (Isaiah 46). In fact, through Cyrus, Babylon will fall (Isaiah 47).

In Isaiah 48 Yahweh calls upon Israel to pay attention and to acknowledge that the idols simply cannot compare with him and his actions in history. Then Yahweh orders the Israelites to “leave Babylon,” thus announcing the end of the exile (48:20).

ISAIAH 49–55—THE SERVANT AND ZION

This unit contains three of the four Servant Songs (49:1–6; 50:4–10; 52:13–53:12). Although in Isaiah 44–45 Cyrus, king of Persia, was to play a leading role in Yahweh’s unfolding plan, now the future focus moves beyond Cyrus (who fades away) to the Servant of Yahweh. The Servant will be the crucial character in bringing about the future restoration and all of the “new things” that Yahweh has planned. The other major theme in this unit is the restoration and renewal of Zion (Jerusalem). These two themes—the Servant and the restored Zion—intertwine throughout this unit.

NT Connection: Simeon

In Luke 2:22–32, when Jesus is still a baby, his parents take him to the temple for the traditional consecration ceremony. Simeon, a righteous man “waiting for the consolation of Israel,” takes the baby in his arms and praises God. Simeon, obviously immersed in the prophecies of Isaiah, identifies the child as “a light for revelation to the Gentiles and for glory to your people Israel,” a twofold aspect very similar to the task assigned to the Servant in Isaiah 49:5–6.

Isaiah 49:1–6 contains the second Servant Song. In 49:1–4 the Servant describes his calling from Yahweh. Next he describes his mission (49:5–6). Yahweh has given the Servant a twofold task: the restoration of Israel, and salvation for the nations (Gentiles). Once again. the Servant is proclaimed to be “a light for the Gentiles [nations].”

Using imagery from the exodus and implying a comparison between the coming Servant and Moses, Isaiah 49:8–12 once again describes the coming restoration of Israel. Isaiah 49:13 calls for shouts of joy and singing in response to the glorious salvation of Yahweh, a theme running throughout the prophets. The personified Zioncries out in the next section (49:14–50:3) that Yahweh has forsaken her, but Yahweh answers with intimate compassionate words of reassurance that the restoration will truly happen.

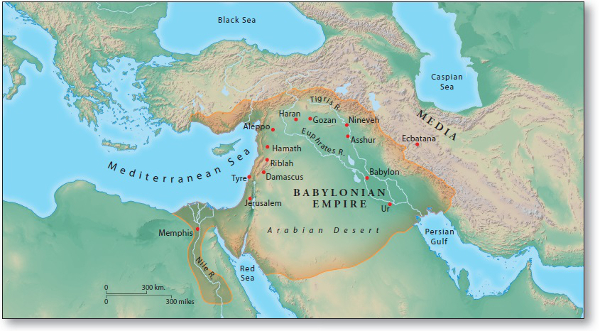

A map of the Babylonian Empire in the early 6th century BC. Isaiah prophesies the fall of Babylon.

The third Servant Song appears in 50:4–9. In this song the Servant declares his trust in Yahweh during difficult times of persecution and ridicule. The following section (Isa. 50:10–52:12) centers again on the restoration of Zion (Jerusalem). Numerous earlier themes reappear: New Exodus motifs, justice and righteousness, comfort for Jerusalem, Yahweh as powerful creator, the eternal nature of Yahweh’s salvation in contrast to humanity’s temporary nature, judgment on the oppressors, and joy and singing in response to Yahweh’s salvation.

The final and climactic Servant Song appears in Isaiah 52:13–53:12. Some scholars have dubbed this passage “the high-water mark of Old Testament prophecy.” Without doubt, this passage is the most famous of the Servant Songs because of its strong messianic prophecies and the many aspects of this text that were fulfilled during the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

Like many other poetic units of prophetic literature, this one has clear structural features. There are five main stanzas, each consisting of three verses (52:13–15; 53:1–3, 4–6, 7–9, 10–12). The first and the fifth stanzas—the opening and the closing of the unit—describe the exaltation of the Servant. This is in strong contrast to the middle three stanzas, which detail the humiliation and suffering of the Servant. Indeed, this contrast is one of the central themes of the poem. Interconnected with this is the irony of the peoples’ misperception of the Servant. Their negative view of him is contrasted with the reality of who he is and what he really will do for them.2

Who is the Servant of Yahweh?

Throughout history there has been much discussion about the identity of the Servant of Yahweh. Recall the puzzlement of the Ethiopian eunuch in Acts 8:32–34 regarding the identity of the Servant in the fourth Servant Song (Isa. 52:13–53:12). The Ethiopian asks of Philip, “Who is the prophet talking about, himself or someone else?”

This is a valid question because Isaiah presents us with some confusing data. Several times Isaiah refers to the people Israel (or Jacob) as Yahweh’s servant (41:8; 44:1; 49:3; implied in 42:18–22). In these texts the term “Servant” seems to have a corporate sense. On the other hand, many of the texts in the Servant Songs clearly refer to the Servant as an individual (e.g., 49:5–6).

Apparently, the people of Israel had been called to be Yahweh’s servant; that is, ones who should obey him and carry out his plan. But in this they failed. The Coming One (i.e., Jesus the Messiah), on the other hand, will be the true or ideal “Israel” in the sense that he will be and do all that Israel failed to be and do. Thus, in response to the Ethiopian’s question, Philip “began with that very passage of Scripture and told him the good news about Jesus” (Acts 8:35). The New Testament clearly identifies Jesus as the Servant who fulfills the tasks assigned to the Servant in Isaiah.

Mount Zion today.

Who would expect that one so lowly and persecuted could ever be so exalted as to sit on the very throne of Yahweh?

In Isaiah 52:13–15 Yahweh speaks, declaring that although the Servant was “disfigured” and people were horrified by his appearance, nonetheless he will be exalted above kings. The second half of 52:15 expresses a certain puzzlement that later finds clarification (“what they have not heard, they will understand”). The startling reality explained in the rest of the passage is that no one ever expected that one so lowly and persecuted could ever be so exalted as to sit on the very throne of Yahweh, having played the crucial role in Yahweh’s great deliverance. In the Gospels, the humble origins of Jesus (from Nazareth and Galilee) frequently led many Jews to doubt that he could be God’s great deliverer.

Isaiah is most likely the speaker of the next three stanzas (53:1–3, 4–6, 7–9). He seems to speak from a time when the suffering of the Servant has been completed but before the actual coming exaltation takes place. Picking up on the contrast of the previous section, Isaiah likewise underscores the contrast between the obscure origins of the Servant (“like a tender shoot, a root out of dry ground”) and the role he will play as the “arm of Yahweh.” “Arm” is a figure of speech that usually refers to great conquering military power (Isa. 40:10; 48:14; 51:5, 9; 52:10; 63:5–6). Not only were the Servant’s origins obscure, the prophet proclaims, but there was nothing majestic about him to attract followers. Most monarchs of the day dressed in elaborate, beautiful clothes and rode spectacular, powerful horses in order to impress the people. This Servant did not come in this fashion. Ironically, he was a “man of sorrows, and familiar with suffering,” and thus he was rejected and despised. How could this one be an exalted conqueror?

“How beautiful on the mountains are the feet of those who bring good news” (Isa. 52:7).

“We all, like sheep, have gone astray” (Isa. 53:6).

Isaiah 53:4–6 proclaims the greatest irony in history. The very one who was despised and persecuted was the one who would bear their suffering and sorrows (the Hebrew words translated as “infirmities” and “sorrows” in 53:4a are identical to those translated as “suffering” and “sorrows” in 53:3a) and provide them with peace and forgiveness. The significance of this passage cannot be overstressed. Isaiah points to one of the most important theological truths of Scripture—one that is not fully explained until the New Testament but that is at the very heart of Christianity: The coming Servant (i.e., the Messiah) will suffer and die as a substitute for those who have sinned. The irony of 53:6 is incredible. “We all,” Isaiah states, “like sheep, have gone astray.” Sheep have a propensity to wander off, but remember that sheep are also the primary animal of sacrifice! Isaiah seems to be saying that we are the sheep, but that the Servant will be the one who dies in our place. This suffering and death of the Servant will bring peace (with God), forgiveness, righteousness (see 53:11), and healing (in a figurative sense).

The coming Servant will suffer and die as a substitute for those who have sinned.

The suffering of the Servant, Isaiah explains, will lead to his death, described in 53:7–9. The Servant is innocent, but he goes quietly and willingly to his death in obedience to Yahweh’s will (53:10–11). In fact, Yahweh breaks in to speak in 53:11, announcing that “my righteous servant will justify [Heb. ‘cause to be righteous,’ i.e., acquit] many.” Then in 53:12, Yahweh speaks of the Servant’s final exaltation because of his obedient death.

Much of Jesus’ life and death as portrayed in the Gospels can be read as a fulfillment of the fourth Servant Song.

The discussion in Isaiah 54 returns to the bright future of Zion. Isaiah uses the marriage analogy, an image frequently employed by the prophets. Zion is the bride, and Yahweh is the husband. She is barren and distraught, but her husband will take her back; she will have many children, and she will know peace.

A Bedouin tent. Isaiah 54:2 uses the imagery of stretching out the cords and enlarging the tent to represent restoration.

“Come, all you who are thirsty, come to the waters” (Isa. 55:1). The Spring of Banias forms the headwaters of the Jordan River.

Isaiah 55 calls the weary, hungry, and thirsty exiles to a great feast. This is the figurative imagery used of the great restoration that is coming. This restoration, this great feast, is a result of the new everlasting covenant, based on the Davidic covenant of 2 Samuel 7, that Yahweh will inaugurate (55:3). Sinners are called upon to repent and be saved (55:7). This is astonishing, but Yahweh reminds them that his ways and his understanding are above the ways and understanding of people (55:8–9). Yahweh’s word is powerful and effective (55:11), leading to the great deliverance that produces joy within his people (55:12).

» FURTHER READING «

Childs, Brevard S. Isaiah. The Old Testament Library. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001.

Goldingay, John, and David Payne. Isaiah 40–55. International Critical Commentary. 2 vols. London and New York: T. & T. Clark, 2006.

Oswalt, John N. The Book of Isaiah: Chapters 40–66. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998.

Smith, Gary V. Isaiah 40–66. New American Commentary. Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2009.

Westermann, Claus. Isaiah 40–66. The Old Testament Library. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1969.

» DISCUSSION QUESTIONS «

- Isaiah frequently ridicules the worship of idols and the fact that people who worship idols are putting their trust in something that they themselves created out of wood or stone. Discuss things that people today trust in that are really their own creations.

- Discuss the irony in Isaiah of referring to the coming deliverer as both Davidic king and suffering servant. How does Jesus fulfill both of these seemingly contradictory images?

» WRITING ASSIGNMENTS «

- Isaiah 42:7 states that the Servant of Yahweh will open eyes that are blind. Discuss how Jesus fulfills this, both literally and symbolically. Be sure to address how the literal healing of blind people often symbolized “seeing” the truth. Look particularly at Mark 8:14–30 and John 9.

- Discuss how the historical details (the arrest, trial, beatings, crucifixion) and the theological significance (substitutionary atonement) of Jesus fulfills specific verses of the fourth Servant Song (Isa. 52:13–53:12).

1These characteristics have been developed from those suggested by Claus Westermann, Isaiah 40–66, Old Testament Library (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1969), 11–21.

2John Oswalt, The Book of Isaiah: Chapters 40–66, New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 376.