CHAPTER 10

Jeremiah 1–10

“If you really change your ways…and deal with each other justly…and if you do not follow other gods…then I will let you live in this place.”

(Jer. 7:5–7)

OVERVIEW OF JEREMIAH

Setting

Isaiah lives and prophesies in Jerusalem during the time of Assyrian expansion and domination. Although Jeremiah also lives and preaches in Jerusalem, his ministry takes place during the time of the Babylonian empire. Perhaps more than any other prophet, Jeremiah repeatedly ties his message firmly into historical events. He begins his ministry in 627 BC during the reign of Josiah (the last good king of Judah), and he prophesies throughout the reigns of Jehoahaz, Jehoiakim, Jehoiachin, and Zedekiah. Most of Jeremiah’s confrontations and conflicts are with Jehoiakim and Zedekiah. Jeremiah experiences the terrible siege and destruction of Jerusalem in 587/586 BC. He continues to prophesy to those who remain in Judah under the governor, Gedaliah, after the destruction and exile, but then he is forced to go to Egypt with those Jews who are fleeing from Babylonian wrath for foolishly assassinating Gedaliah. For a review of this time period, reread chapter 2, “The Prophets in History,” especially the part from King Manasseh’s reign in Judah (687–642 BC) to the fall of Jerusalem (587–586 BC). This history provides important background material for understanding the message of Jeremiah.

Although the spoken messages of Jeremiah and the events portrayed in the book take place just before and after the fall of Jerusalem, the final compilation of the book probably took place a short time later. Jeremiah 1:2–3 describes the duration of Jeremiah’s ministry, which continues into the time “when the people of Jerusalem went into exile.” This reveals to us the final point of view of the book. While Jeremiah’s preached verbal message was “Repent! The Babylonians are coming!” the written final form of the message is probably targeted at the people in exile, providing an explanation for the tragedy: “Look at what happened because you didn’t repent and trust in Yahweh!” Moreover, the fall of Jerusalem and the Babylonian exile exonerated Jeremiah, proving him to be the true prophet of Yahweh with the true word of Yahweh for his people, thus adding great weight to his promise of future restoration and blessing.

Message

The three-point standard preexilic prophetic message discussed in chapter 4 is an excellent synthesis of Jeremiah. Thus Jeremiah’s message can be summarized as follows:

- You (Judah) have broken the covenant; you had better repent!

- No repentance? Then judgment! Judgment will also come on the nations.

- Yet there is hope beyond the judgment for a glorious future restoration both for Israel/Judah and for the nations.

Like many of the other prophets, Jeremiah focuses on the three central indictments that underscore how seriously Judah has broken the covenant. These indictments (sins or infractions against the covenant) are idolatry, social injustice, and religious ritualism. These three will surface time and time again in Jeremiah. Furthermore, like most of the other prophets, Jeremiah draws heavily from the book of Deuteronomy.

The book of Jeremiah provides more insight into the prophet himself than does any other prophetic book. We are provided with glimpses into his internal fears and struggles through a series of “laments” or “confessions.” Because of his “lamenting,” scholars have often labeled Jeremiah “the weeping prophet.” However, it may be more appropriate to call him the “Dirty Harry” of the Old Testament. As in the case of policeman Harry Callahan in the old Clint Eastwood movies, Jeremiah is given a very tough job that no one else would want. Throughout the book, Jeremiah is engaged in serious (and dangerous) conflict with the political powers in Jerusalem—the king, the king’s prophets, the nobles, and the priests.

The Nature of the Book of Jeremiah

Ironically, even though the book of Jeremiah has numerous references to kings and other historical events, only Jeremiah 37–44 is in chronological order. The rest of the book hops back and forth from one king to another. The structure and order seem to be based on thematic elements or even on word repetitions rather than chronological sequence. Also, in general, Jeremiah is like an anthology, a collection of poetic oracles and proclamations, narrative events, and dialogues. It is very difficult if not impossible to outline the book in detail, and often the connection between literary units is unclear. However, the overall message as discussed above is very clear, and Jeremiah repeats the three indictments (idolatry, social injustice, religious ritualism) and the three main points (broken covenant, judgment, restoration) over and over. Likewise, while tight logical connections between small sections are not always discernible, the book can be broken down into larger sections that are unified by broad, general themes:

Jeremiah 1–29—The Broken Covenant and Imminent Judgment

Jeremiah 30–33—Restoration and the New Covenant

Jeremiah 34–45—The Final Days of Jerusalem and Judah

Jeremiah 46–51—Oracles Against the Nations

Jeremiah 52—Postscript

An interesting problem in the book of Jeremiah is the textual issue. The Old Testament portion of our English Bibles is largely translated from Hebrew manuscripts that are referred to as the Masoretic Text (MT). Prior to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1948, the earliest MT manuscript of Jeremiah dated to around AD 900. Another important ancient manuscript is the Septuagint, often referred to as the LXX. The LXX is a Greek translation made from the Hebrew Old Testament around 200–150 BC. The LXX was the primary Old Testament used by the early church until the fourth and fifth centuries AD. In Jeremiah, the MT and the LXX differ in several significant ways. First of all, the LXX is one-eighth shorter than the MT; that is, numerous passages and phrases in the MT are missing from the LXX. Significant passages that are in the MT but not in the LXX include Jeremiah 33:14–26; 39:4–13; 51:44b–49a; and 52:27b–30. In addition, some verses have a different word order or vary slightly in the words included. Furthermore, in the LXX, the text of Jeremiah 46–51 (the oracles against the nations) does not follow after Jeremiah 45, but follows Jeremiah 25:13, and before Jeremiah 26.

The Septuagint version of Jeremiah is one-eighth shorter than that in the Masoretic Text.

For much of the twentieth century it was thought that the MT was a better reflection of the original than the LXX. However, when the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, one of the ancient Hebrew fragments of Jeremiah reflected the reading of the LXX rather than the MT, suggesting that the LXX was an accurate translation of an ancient Hebrew text that was older than the MT. Some other fragments, however, followed the MT.

Scholars disagree as to how we should view these differences. Some argue that the MT is the superior text and thus it should be followed. On the other hand, some argue that the LXX reflects an earlier tradition and thus is superior to the MT. Others suggest that perhaps two different editions of Jeremiah were composed, one in Babylon (the basis of the MT) and one in Egypt (the basis of the LXX). Thus both editions could be viewed as the inspired word of God.1 At any rate, while the textual differences are significant, there are no significant theological differences between the two versions, and the central message of Jeremiah is clear in both traditions.

Another unique feature of Jeremiah is the detail given in regard to its writing. Unlike the other prophetic books, the book of Jeremiah mentions several times the actual writing down of the prophet’s words onto a scroll. For example, Jeremiah 36:4, 28, 32 indicates that Jeremiah dictated a fairly large portion of the book to Baruch (his colleague and scribe), who wrote the material down. Based on the time references given in the text, the scroll mentioned in Jeremiah 36:32 may have included most of Jeremiah 1–25. At the end of Jeremiah 36:32 are the words: “And many similar words were added to them,” indicating an expansion of the scroll that Jehoiakim had burned in Jeremiah 36:20–26. But even if one concludes that Jeremiah was responsible for the writing and composition of the book, it is improbable that he wrote the last chapter. At the end of Jeremiah 51 the text reads, “The words of Jeremiah end here.” So the book itself indicates that someone other than Jeremiah wrote Jeremiah 52.

JEREMIAH 1—YAHWEH CALLS A RELUCTANT PROPHET

Unlike Isaiah, the book of Jeremiah starts with the prophet’s divine call. Significant aspects of Jeremiah’s call include the following: (1) Yahweh is the one who calls; (2) Yahweh chose him for this task before he was even born; (3) the call centers on the proclamation of the word of Yahweh; (4) Yahweh will empower the young Jeremiah to speak this word; (5) opposition, even persecution, is promised; and (6) Yahweh promises his empowering presence (“I am with you”). There is no “health and wealth” promise in Jeremiah’s call.

In Jeremiah 1:9–10 Yahweh informs the young prophet that he has been appointed “over nations and kingdoms to uproot and tear down, to destroy and overthrow.” This imagery will occur frequently in Jeremiah, especially in the first 29 chapters, for they focus on judgment. However, Yahweh also promises Jeremiah that by the power of his word he will “build and plant,” the opposite images of “uproot and tear down.” The figurative imagery of building and planting will also be used frequently throughout the book of Jeremiah, especially in restoration passages such as Jeremiah 30–33.

Jeremiah sees an almond tree like this one. The Hebrew word for “almond tree” sounds similar to the Hebrew word for “watching.”

Yahweh then shows Jeremiah two significant visions (1:11–14). First the prophet sees an almond tree. The Hebrew word for “almond tree” (shākēd) sounds very similar to the Hebrew word for “watching” (shōkēd). The vision of the almond tree (shākēd) indicates that Yahweh is certainly watching (shōkēd) to be sure that his word is indeed fulfilled. Thus Yahweh declares the certainty of his prophetic word. Then Jeremiah sees a vision of a boiling pot, tilted away from the north, apparently about to tumble over and spill boiling water over the area to the south of it. This is a reference to the coming Babylonian invasion. Yahweh then declares, “Their kings will come and set up their thrones in the entrance of the gates of Jerusalem” (1:15), stating very clearly from the beginning that Jerusalem will fall to the Babylonians.

JEREMIAH 2—THE INDICTMENTS AGAINST JUDAH

Jeremiah 2 stresses the personal, intimate injury against Yahweh that Judah has inflicted through their idolatrous behavior.

Jeremiah 2 presents the formal indictments against Judah; that is, Jeremiah immediately proclaims the central sins of Judah. In this chapter the sin that is stressed is idolatry, although social injustice is mentioned briefly at the end. While there are formal, legal aspects of covenant violation, this chapter stresses the personal, intimate injury against Yahweh that Judah has inflicted through their idolatrous behavior. Three times Yahweh declares that they have “forsaken” him (2:13, 17, 19). Throughout this chapter, as well as throughout the book, Jeremiah uses the common prophetic motif of Judah/Israel as the unfaithful, adulterous wife and Yahweh as the wronged husband. Chasing after foreign gods is paralleled to a wife having adulterous affairs with other men. Yahweh recalls the good days at the beginning of the “marriage” (i.e., during the exodus) (2:2), and how he loved them and blessed them. “What fault did your fathers find in me?” Yahweh asks (2:5), seemingly puzzled at why Israel should abandon him after all the good things he has done for them. Yahweh’s criticism of Israel’s unfaithfulness is scathing in this chapter. In 2:24 he compares them to a wild female donkey in heat.

JEREMIAH 3:1–4:4—THE CALL TO REPENTANCE

Throughout this unit Yahweh repeatedly calls on the people to turn back to him (3:12, 14, 22; 4:1). Moving beyond the image of the adulterous wife, in 3:2–5 Yahweh states that Israel has become like a hardened prostitute who no longer blushes with shame at her actions. That is, Israel no longer even acknowledges her sin as sin. “Acknowledge your guilt,” Yahweh pleads with his people (3:13).

In 3:6–11 Jeremiah describes Israel and Judah as two sisters. The older sister (Israel) committed adultery and was sent away (i.e., conquered by the Assyrians). Therefore, certainly the younger sister Judah should take heed and learn from the mistakes of her sister. But of course she doesn’t. Ezekiel will use this same analogy and even develop it further.

In the midst of this call to repentance is a glimpse of the future restoration (Jer. 3:14–18). Yahweh describes a time when the ark of the covenant (the symbol of the old Mosaic covenant) will be gone and not even missed anymore. As the book of Isaiah also describes, this future time will be characterized by the presence of Yahweh in Jerusalem and by the gathering of the nations there to worship him.

Shūv! Shūv! Shūv!

The Hebrew word shūv is one of Jeremiah’s favorite words, occurring more than one hundred times in the book. Theologically, it lies at the heart of his message. The basic meaning of shūv is “to turn.” However, it can mean “to turn to,” “to turn back,” or “to turn away.” Thus Jeremiah uses shūv as his central word for “repent” (i.e., a turning away from sin and a turning to Yahweh). On the other hand, Jeremiah also uses shūv for turning away from Yahweh. So shūv can refer either to true repentance or to apostasy. Jeremiah is fond of wordplay, and he employs the multiple meanings possible for this word in numerous ways. In Jeremiah 3:1–4:4 (the call to repentance) shūv occurs eleven times. In Hebrew, Jeremiah 3:22 only has five words, and three of the words are forms of shūv. The English text reads, “Return, faithless people; I will cure you of backsliding.” If we are allowed to mix the Hebrew and English word forms a bit, the text would literally read, “Shūv, sons of shūving, I will cure you of your shūvings.” Likewise, note the repeated use of shūv in Jeremiah 8:4b–5: “When a man turns away [shūv] does he not return [shūv]? Why then have these people turned away [shūv]? Why does Jerusalem always turn away [shūv]? They cling to deceit; they refuse to return [shūv].” Both the proclamation of apostasy (turning away from Yahweh) and the call to repentance (turning to Yahweh) are central themes in Jeremiah, and they both center on the word shūv.

NT Connection: The Spring of Living Water

Jesus is probably drawing from Jeremiah 2:13 when he talks to the Samaritan woman about drinking from the “spring of living water” in John 4.

JEREMIAH 4:4-6:30—INEVITABLE AND TERRIBLE JUDGMENT

The prophet Jeremiah charges the nation with serious sin in Jeremiah 2 and then calls on them to repent in Jeremiah 3. Judah, however, is obstinate and rebellious, refusing even to acknowledge her sin, much less to repent and turn back to Yahweh. Thus in Jeremiah 4:4–6:30 the prophet describes the horrific judgment that is coming—an invasion by the Babylonian army. The alarm trumpets are sounded and signals sent. Everyone is fleeing to fortified cities before the invaders (4:5–6). The Babylonians come rapidly, with swift horses and chariots (4:13). The enemy comes from the north and moves south across Israel and Judah toward Jerusalem (4:15; from Dan in the far north to Ephraim in the middle, etc.). In Jeremiah 4:19–21 the prophet seems to actually see the coming destruction and all of the terrible things that will happen.

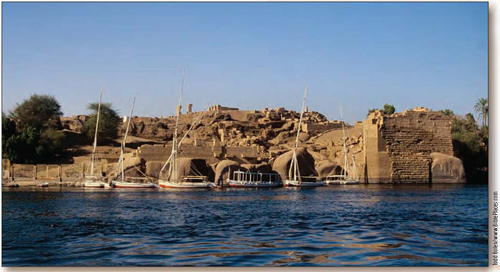

Elephantine Island, located on the Nile River in Egypt. A significant Jewish settlement was here during the Persian Era.

What Happened to the Ark of the Covenant?

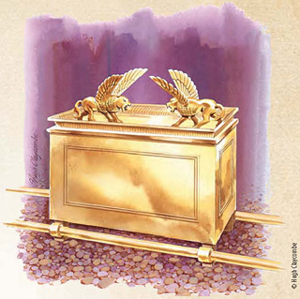

Yahweh describes a time when the ark of the covenant will be gone but not even missed anymore.

During the exodus, Yahweh gave instructions to Moses regarding how to build the ark of the covenant (Exodus 25). The ark was a rectangular box (approx. 4’ x 21/2’ x 21/2’), covered with gold inside and out. On top of the ark was a golden cover, shaped into the “mercy seat,” with gold cherubim on either side. The ark of the covenant played a critical role in the early history of Israel; indeed, it was the focal point for the very presence of Yahweh, and it was thus also associated with Yahweh’s great power. The ark was an integral part of the Holy of Holies, first in the tabernacle and later in the temple.

In Jeremiah 3:16, the prophet Jeremiah makes the audacious proclamation that in the future the ark of the covenant will cease to exist. What’s more, Jeremiah announces, no one will even miss it, and a replacement will not be built. As Jeremiah predicts, due to the continued apostasy of Judah and Jerusalem, the Babylonians eventually conquer Judah and destroy Jerusalem completely. No mention is made in Jeremiah or in 2 Kings about the fate of the ark as Jerusalem falls to the Babylonians. In all likelihood the Babylonian army melted the ark down and carried the gold back to Babylon along with the other treasures they captured.1

However, numerous legends, rumors, and speculations about what actually happened to the ark have emerged and have continued to circulate for centuries. One dubious Jewish tradition postulates that Jeremiah himself took the ark of the covenant and secreted it beneath the Temple Mount just before the Babylonians captured Jerusalem. Most Old Testament scholars find this to be quite unlikely.

Another account of what happened comes from Ethiopia. According to national folk legend, the Queen of Sheba, who ruled the area now known as Ethiopia, visited King Solomon in Jerusalem and later gave birth to Solomon’s son. When he grew older, the son, named Menilek, visited Jerusalem to see Solomon, but then stole the ark of the covenant from the temple and carried it back to his home. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church claims that the ark remains to this day in a special, guarded church in the ancient city of Aksum (which was the center of Menilek’s kingdom and the seat of the Aksumite dynasty for many years). Unfortunately for scholars, church authorities will not let outsiders enter the supposed resting place of the ark.

The major problem with this account is that the details of the story do not accord well with history. King Solomon’s reign in Israel predates the Aksumite kingdom of Menilek by about one thousand years. Thus it is highly unlikely that Solomon was Menilek’s father. On the other hand, the Ethiopian legend cannot be totally dismissed. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church does apparently have something in that guarded church in Aksum that is very, very old and yet related to the ark in some way. In addition, the religious festivals of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church incorporate models of the ark into their ritual processions, a tradition that can be traced back hundreds of years. How did such a custom get started? Why does the ark of the covenant play such an important and significant role in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church when no other branch of Christianity uses it in such a manner?

An artist’s rendition of the ark of the covenant.

One explanation that has been offered relates to a Jewish colony in Upper Egypt. Near the beginning of the sixth century BC, Jewish mercenaries were hired by the Egyptians to build and defend a fortress on the island of Elephantine in the Nile. A Jewish community thus grew up around this fortress in Upper Egypt. However, after around two hundred years, this Jewish community disappeared from history. During the twentieth century, archaeological excavations on the island of Elephantine discovered the ruins of the settlement that these Jewish mercenaries had built, including what appears to be the ruins of a model of the Jewish temple in Jerusalem. Some scholars have suggested that if these Jews in Egypt built a model of the temple, then they probably also built a model of the ark of the covenant to place in the temple. What happened to these Jewish settlers? No one knows for certain, but some scholars have posited that these Jewish mercenaries may have migrated east into Ethiopia and settled there, carrying their replica of the ark with them. This theory at least provides a plausible explanation of how the Jewish ark of the covenant came to be so central to the festivals and worship ceremonies of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. If this explanation is correct, the Ethiopians have a very old (and significant) religious box in Aksum, but not the original ark of the covenant.

As mentioned above, however, the most probable fate of the ark is that it was captured and destroyed by the Babylonians. Whatever really happened to the ark of the covenant, it did indeed disappear, in accordance with Jeremiah’s prophecy.

The point that Jeremiah is stressing in Jeremiah 3:16 is that in the future the presence of Yahweh will no longer be located in the temple; thus the ark of the covenant will no longer have a central role to play. Highlighting the irony of Jeremiah’s prophecy is the fact that the inhabitants of Jerusalem were superstitiously relying on the ark of the covenant to magically protect them from the Babylonians. Jeremiah tells them that the ark itself will soon disappear (and not be needed in the new covenant era). The fulfillment of Jeremiah’s prophecy begins with the disappearance of the ark after the Babylonians capture Jerusalem. Ultimately, Jeremiah’s prophecy finds fulfillment in the New Testament era when God’s presence dwells within each believer through the Holy Spirit rather than in the temple around the ark. As Jeremiah predicted, God’s people today have God’s presence dwelling directly within them through the Holy Spirit, and they have direct access to God through Jesus Christ. Thus no one even misses the ark.

1K. A. Kitchen, “Ark of the Covenant,” in New Bible Dictionary, 3rd ed., ed. I. H. Marshall et al. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVar sity Press, 1996), 81.

In Jeremiah 5:1, Yahweh challenges Jeremiah to search the streets of Jerusalem and find even one person who is honest and who seeks the truth. Find one, Yahweh states, and Jerusalem will be forgiven. This is an obvious allusion to Genesis 18:16–33, where Abraham negotiates with Yahweh over how many righteous people need to be in Sodom to avert the judgment. There Abraham argues God down to ten people. Here Yahweh suggests that Jerusalem does not have any, making the startling suggestion that Jerusalem is worse than Sodom and certainly worthy of the imminent judgment. In 5:3–5 Jeremiah searches among the poor and among the leaders, but comes up empty-handed.

Throughout Jeremiah, wounds and sickness will be used figuratively for sin, with healing used as a symbol for forgiveness and restoration.

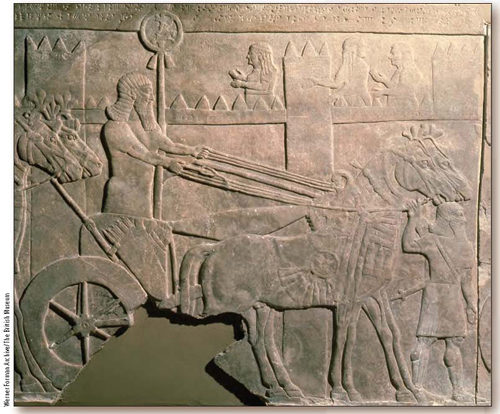

An Assyrian relief depicting the king in his chariot. The prophets refer frequently to the chariots of the invaders (e.g., Jer. 4:13).

NT Connection: A Den of Robbers

When Jesus finds the market and moneychangers in the temple, he quotes directly from Jeremiah 7:11, stating that they have made the temple into a “den of robbers” (Matt. 21:13; Mark 11:17; Luke 19:46). The irony of Jeremiah 7 is that the robbers come to the temple for safety (a den of robbers would be a safe resting place, their hideout). They come right before the holy and powerful presence of Yahweh, the very one they have offended, and the one who is bringing punishment on them. The judgment context of Jeremiah 7 is an important background to understanding Jesus’ comment. He is implying the same thing that Jeremiah states clearly—the sin and disobedience in Jerusalem will lead to its destruction. For Jeremiah’s audience, this occurred in 587/586 BC, and for Jesus’ audience this occurred in AD 70, when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem and the temple.

Other significant themes appear in this unit. The concept of the “remnant” is introduced into Jeremiah as Yahweh states that he will not destroy everyone in the judgment (5:10, 18). The charge of social injustice is made, especially against the wealthy and the leaders (5:26–31). Likewise, in light of their profound sin, Yahweh dismisses their religious rituals (6:19 – 20).

Another motif introduced in this section is that of sickness and healing (6:7, 14). Wounds and sickness will be used figuratively for sin throughout Jeremiah (and the other prophets), with healing used as a symbol for forgiveness and restoration. Another common theme introduced here is that the theological leaders of Judah (court prophets and priests) declare that Jeremiah is wrong about the judgment. Everything is all right, they counter: the people are not really sinning. These leaders continually predict peace, while Jeremiah predicts death and destruction (6:13–15).

JEREMIAH 7 – 10—FALSE RELIGION AND ITS PUNISHMENT

Jeremiah 7–10 focuses on the particularly serious sin of idolatry within Jerusalem. Coupled with this is Yahweh’s rejection of their syncretistic religious rituals. In 7:1–15 Jeremiah delivers a message in the temple (called the “Temple Sermon”). The actual results of this sermon are chronicled in Jeremiah 26. If they will really change their ways, Jeremiah tells them, and if they will truly care for the orphans, widows, and foreigners, and if they will abandon their idolatry, then Yahweh will avert the coming judgment and they can stay in Jerusalem (7:2–11). The people, however, continue to break the Ten Commandments habitually, especially in regard to idolatry (7:9), and then they have the audacity to come to the temple expecting Yahweh to give them safety. Yahweh responds with incredulity. Look at what happened to Shiloh, Yahweh points out, where the tabernacle once was housed. Just as Shiloh was destroyed, so will be Jerusalem (7:12–15).

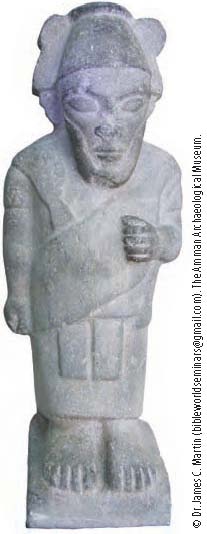

A Canaanite idol, perhaps Chemesh, associated with the Moabites and Ammonites and often associated with child sacrifice.

Jeremiah 7:30–34 describes what is perhaps the most horrific and disgusting sin of Jerusalem. The prophets often mention the abhorrent worship of Molech and Chemesh, usually adding a comment such as “those detestable gods of the Ammonites and Moabites.” What was particularly abhorrent about worshipping these idols was that it required child sacrifice. At the time of Jeremiah, the people of Jerusalem had built “high places” (sacrificial sites) at which they sacrificed their children, in the Valley of Ben Hinnom, which was right outside the walls of Jerusalem! Yahweh declares that in the coming judgment this valley will be filled with the dead bodies of those who have perpetrated such terrible sins (7:30–34).

Throughout Jeremiah 7, Yahweh underscores that the people have not listened to him or obeyed him (the same word in Hebrew is used for both nuances). Jeremiah 8 focuses on the lies and deceit that they have been listening to instead, all of which will lead them astray. One of the main motifs in Jeremiah 9 is wailing, a phenomenon in the ancient world that normally accompanied tragedies (like a horrific invasion). The message of Jeremiah 8:4–9:25 appears to connect these two themes, stating that because the nation has foolishly listened to lies rather than to the voice of Yahweh, what they will hear next is wailing, the sound of judgment.

The people had built “jhigh places” in the Valley of Ben Hinnom, where they practiced child sacrifice right outside the walls of Jerusalem.

The ruins of ancient Shiloh. Yahweh said that if the could destroy Shiloh because of her wickedness, then he could likewise destroy Jerusalem (Jer. 7:12–15).

Because the people of Judah have foolishly listened to lies rather than to the voice of Yahweh, what they will hear next is wailing, the sound of judgment.

A Canaanite god, perhaps El.

Jeremiah 10:1–16 sounds very much like Isaiah. Yahweh ridicules the idols and those who worship them. The idols are “like a scarecrow in a melon patch,” Yahweh declares. They can’t walk or talk; thus they can’t help you or hurt you either (10:5). Yahweh, on the other hand, is the all-powerful, all-wise creator of heaven and earth with control over all the nations and all creation (10:6–15). His judgment and his wrath are to be feared, not those of the idols.

» FURTHER READING «

Clements, R. E. Jeremiah. Interpretation. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1988.

Craigie, Peter C., Page H. Kelley, and Joel F. Drinkard Jr. Jeremiah 1–25. Word Biblical Commentary. Dallas: Word Books, 1991.

Dearman, J. Andrew. Jeremiah/Lamentations. NIV Application Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2002.

Hays, J. Daniel. “Jeremiah, the Septuagint, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and Inerrancy: Just What Exactly Do We Mean by the ‘Original Autographs’?” In Vincent Bacote et al., Evangelicals and Scripture: Tradition, Authority and Hermeneutics. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2004.

Fretheim, Terence E. Jeremiah, Smith & Helwys Bible Commentary. Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys, 2002.

Holladay, William L. Jeremiah, Vol. 1. Hermeneia. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986.

Longman, Tremper. Jeremiah, Lamentations. New International Biblical Commentary. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2008.

McConville, J. Gordon. Judgment and Promise: An Interpretation of the Book of Jeremiah. Winona Lake, IN and Leicester, UK: Eisenbrauns and Apollos, 1993.

McKane, William. Jeremiah, Vol. 1. International Critical Commentary. Edinburgh and New York: T. & T. Clark, 1986.

Thompson, J. A. The Book of Jeremiah. The New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980.

» DISCUSSION QUESTIONS «

- Discuss the relevance of Jeremiah 6:13–15 for the church today.

- What are the differences between the text of Jeremiah in the Septuagint and in the Masoretic Text?

- Discuss the meaning of Jeremiah 9:23–24 in its relation to the prophetic message. How do kindness, justice, and righteousness relate to the prophetic message? How does this passage relate to today?

» WRITING ASSIGNMENTS «

- Compare and contrast the call of Jeremiah with the call of Isaiah (Isaiah 6). Include a discussion of what kind of success and what kind of opposition Yahweh promises each of them. What relevance does this have for being called into ministry today?

- Read 4:5–31. (a) Discuss the sequence of events and identify the invader that Jeremiah sees in: 4:5–6; 4:13–17; and 4:29. (b) Describe the actions of the individual in 4:30. How is her response to the invasion different from those in 4:29? Explain the reason for her approach to the invaders. What happens to her (4:31)? (c) Which other scripture passage is Jeremiah referring to in 4:23? What is the point of 4:23?

- Read 5:1 – 5. Which patriarchal story is the background for 5:1? Briefly compare and contrast that story with the situation Jeremiah addresses. What are the charges that Jeremiah makes in 5:26–31? Who are the charges against?

- Trace the theme regarding the leaders (especially the king, priests, prophets) of Judah in Jeremiah 1-10.

1See the discussion by J. Daniel Hays, “Jeremiah, the Septuagint, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and Inerrancy: Just What Exactly Do We Mean by the ‘Original Autographs’?” in Vincent Bacote, et al., Evangelicals and Scripture: Tradition, Authority and Hermeneutics (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004), 133–49.