CHAPTER 25

Zephaniah

“Be silent before the Sovereign LORD, for the day of the LORD is near.”

(Zeph. 1:7)

OVERVIEW OF ZEPHANIAH

Setting

Zephaniah is one of the six prophetic books in the Book of the Twelve that opens with a historical superscription. His ministry is placed during the reign of Josiah, one of the few good kings of Judah (640 – 609 BC). Thus Zephaniah overlaps with the beginning of Jeremiah’s ministry. Not surprisingly, much of the language of Zephaniah is very similar to Jeremiah’s. Also, remember that Josiah was quite an exception to the rule; the kings before him (primarily Manasseh, 687 – 642 BC) and the kings after him (Jehoiakim and Zedekiah) all turned away from Yahweh. Zephaniah’s message of judgment, like Jeremiah’s, appears directed at disobedient Jerusalem—there is no mention of Josiah’s short-lived reforms in Zephaniah.

The word of Yahweh comes to Zephaniah toward the end of the Neo-Assyrian era. For much of the first half of the seventh century BC, the two main powers in the Ancient Near East were Assyria (the most powerful) and Cush (rulers of Egypt and challengers of Assyrian power). The Cushites ruled Egypt from 710 BC until 663 BC, during which time relations between Egypt and Judah were close, both commercially and militarily. Indeed, throughout the first half of the seventh century BC, the Cushites maintained a strong presence throughout Palestine. The end of Cushite rule in Egypt was marked by the tumultuous destruction of Thebes by the Assyrians in 663 BC, a scant thirty years or so before the prophetic ministry of Zephaniah began. This significant event marked the high point of Assyrian expansion and, ironically, the beginning of the Assyrian decline. Zephaniah prophesies in this context.

Message

Zephaniah’s message is typical of the preexilic prophets and follows the standard three-point pattern: (1) You (Judah) have broken the covenant; you had better repent! (2) No repentance? Then judgment! (3) Yet there is hope beyond the judgment for a glorious future restoration. Zephaniah’s indictments against Judah are likewise the common prophetic indictments: idolatry, social injustice, and religious ritualism. The stress in Zephaniah is on judgment and restoration.

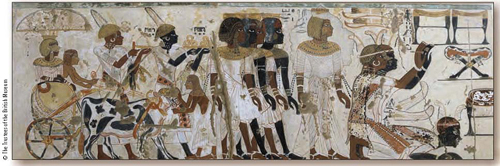

A wall painting from Thebes depicting Cushite princes bowing to the Egyptian king. In the late eighth century BC, however, the Cushites conquered and ruled over Egypt.

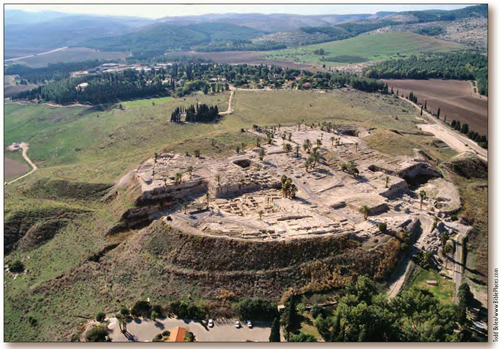

An aerial view of Megiddo. King Josiah was killed in battle by the Egyptians near here as the Egyptian army marched north to fight the Babylonians (609 BC).

Within the Book of the Twelve, Zephaniah closes out the subunit of Nahum-Habakkuk-Zephaniah, which focuses on judgment. Zephaniah emphasizes the day of Yahweh—a central theme in the Book of the Twelve—more than any of the other prophets. Zephaniah clearly ties the day of Yahweh to two quite different aspects. This coming day will be a time of judgment on rebellious Judah as well as on the surrounding haughty nations that defy Yahweh. Yet it will also be a time of blessing on the faithful remnant of Judah along with those Gentiles from among the nations who come to worship Yahweh. Thus the day of Yahweh is linked to judgment and to restoration, both for Judah and for the nations.

At the end of Habakkuk, the prophet declares, “Yahweh is in his holy temple; let all the earth be silent before him” (Hab. 2:20). The book of Zephaniah, which follows in the Book of the Twelve, apparently connects to this phrase by stating near the beginning, “Be silent before Yahweh the Lord” (Zeph. 1:7). In connection to his central theme, however, Zephaniah drives home the ominous reason for this silence: “for the day of Yahweh is near.”

There is no consensus among scholars regarding how to outline the prophecies of Zephaniah. As has been noted several times, the prophetic books are more like anthologies than modern essays and thus are often not easy to outline. Likewise, between the various identifiable units in Zephaniah are complex transitional passages that can connect with both the preceding and the following sections, adding to the difficulty of determining when units start and stop. One of the more traditional ways to outline Zephaniah is as follows:

1:1 Superscription

1:2 – 2:3 The day of Yahweh will bring judgment

2:4 – 15 Judgment on the nations

3:1 – 8 Judgment on Jerusalem

3: 9– 13 Restoration of Jerusalem and the nations

3:14 – 20 Rejoicing in Yahweh’s salvation

ZEPHANIAH 1:1—THE SUPERSCRIPTION

Within the prophetic literature, the genealogy of Zephaniah is very unusual.

The book of Zephaniah opens with an unusual superscription: “The word of Yahweh that came to Zephaniah son of Cushi, the son of Gedaliah, the son of Amariah, the son of Hezekiah, during the reign of Josiah son of Amon king of Judah.” In addition to the fact that Zephaniah’s father was named Cushi (“Cushite”), the genealogy of Zephaniah is unusual in the prophetic literature because it goes back four generations, a feature unique among the identifying lineages of the prophets. Scholars are divided on the reason.

Those who identify the Hezekiah of Zephaniah’s lineage with King Hezekiah see the royal connection as a reason for the extralong genealogy. It is possible that the reforms of Hezekiah may be implicitly connected to the upcoming reforms of Josiah, thus giving a reason for connecting Zephaniah back to his royal ancestor. Also, note that Hezekiah was the king during the great Assyrian/Cushite collision (715 – 687 BC), the events of which provide much of the background for the oracle in Zephaniah 2:1 – 3:13.

On the other hand, several scholars question whether this Hezekiah is to be identified with the famous king. They suggest that the citing of four generations of ancestors was required in order to establish Zephaniah’s legitimate Judahite heritage, a legitimating that was required precisely because his father was named “Cushite.” The evidence, however, appears to weigh in favor of identifying Zephaniah’s ancestor Hezekiah with the earlier king.

ZEPHANIAH 1:2 – 2:3—THE DAY OF YAHWEH WILL BRING JUDGMENT

Unlike Jeremiah, Zephaniah skips over any call to repentance and opens with an extended description of the terrible wrath of Yahweh that will accompany the coming day of Yahweh. Zephaniah uses the term “that day” in reference to the day of Yahweh throughout this section (the term occurs 17 times in 1:2 – 2:3). In the opening verses (1:2 – 3), Yahweh declares that his judgment will be on the entire creation; indeed, as in the flood judgment during the time of Noah, this day of Yahweh will entail a reversal of the creation story. Yahweh will sweep away men and animals (created on day 6) as well as birds of the air and fish of the sea (created on day 5). Likewise, in the wordplay of the final half of 1:3, Yahweh alludes to reversing creation when he states that he will cut off adam (mankind) from the face of the adamah (earth, dirt, ground, the substance that Adam was created from). The severity of this imagery is similar to Jeremiah 4:23, in which the prophet declares, “I looked at the earth, and it was formless and empty; and at the heavens, and their light was gone.” The day of Yahweh is not going to be some minor disciplinary action, but rather an earthshaking event comparable to the Genesis flood.

Zephaniah the Son of Cushi, “the Cushite”

For several generations prior to Zephaniah, the geopolitical world of the Ancient Near East was dominated by the struggle between the Assyrians and the Cushites (who ruled Egypt). In light of this historical context, it is perhaps not all that surprising that Zephaniah mentions Cushites three times in his three short chapters.

However, it is perhaps unusual to be informed at the beginning of the book that Zephaniah’s father is named “Cushi,” or “the Cushite.” In light of the important role that genealogies usually play throughout the Ancient Near East and certainly in the Old Testament, it is valid to explore the implications of Zephaniah being the son of a man named Cushi. The Hebrew term Cushi (lit. “Cushite”) clearly refers to the kingdom of Cush, an African kingdom located on the Nile to the south of Egypt. It is logical to suppose that the owner of the name Cushi would be related to Cush in some manner. This is even more pertinent when a date for the birth of Zephaniah’s father is estimated (perhaps around 685 BC). At that time, Cush was one of the two major world powers.

Recall from chapter 2 that in 701 BC Sennacherib, the Assyrian king, drove the Cushites out of Israel and down into Egypt. However, the Assyrians did not completely subdue the Cushites at that time, and the African kingdom subsequently quickly reemerged as a significant power in the region, routing the Assyrians in 674 BC and sending the proud army of Esarhaddon back to Assyria in defeat. Soon after, however, the Assyrians returned and, led by Ashurbanipal, marched into Egypt to finally subdue the Cushites. On this campaign, Ashurbanipal took numerous vassal kings with him, including Manasseh, the king of Judah and the grandfather of Josiah.

It was during this tumultuous time, when the Cushites were extremely involved in the commercial, diplomatic and military affairs of Judah, that Zephaniah’s father was born and given the name “Cushite.” It is interesting to note that Jeremiah 36:14 refers to an official in Jerusalem with a great-grandfather named “Cushi.” This individual would probably have lived at about the same time period as Zephaniah’s father. Thus we know of two Israelites living in Jerusalem around the turn of the seventh century that have the name “Cushi.” Perhaps it was a popular name.

Scholars have suggested four plausible reasons why someone might be named Cushi: (1) the person was actually an ethnic Cushite; (2) the person had dark skin and looked like a Cushite; he may even have had a Cushite mother, father, or grandparent; (3) he was born in Cush, even if he had Judahite parents; or (4) he was given the name Cush in honor of the Cushites, recognizing the importance of Cush as an ally against the Assyrians. The historical context suggests that Cushite soldiers, diplomats, and traders would have been in Judah frequently during this time; thus, any of the four scenarios described above would have been possible.1

1J. Daniel Hays, From Every People and Nation: A Biblical Theology of Race, New Studies in Biblical Theology (Downers Grove, IL: Inter Varsity Press, 2003), 121 – 27.

The focus of this section is judgment on Jerusalem and Judah, especially because of their blatant idolatry (1:4 – 6). Zephaniah stresses that the day of Yahweh is near (1:7, 14) and that the accompanying judgment will fall on the nobility (1:8), the corrupt priests (1:4, 6, 9), and the wealthy (1:10 – 13, 18), including those who are merely complacent (1:12). However, the final line of 1:18 indicates (at least poetically) that the entire world will be consumed by Yahweh’s jealous wrath.

Zephaniah 2:4 – 15 moves around the points of the compass: Philistia to the west, Moab and Ammon to the east, Cush to the south, and Assyria to the north.

Zephaniah 2:1 – 3, however, inserts a warning and an exhortation to “seek Yahweh.” In contrast to the destruction of the arrogant and haughty leaders of Judah, Zephaniah calls on humble and obedient people to seek Yahweh. This exhortation closes with a call to seek righteousness and humility in order to find shelter from Yahweh’s wrath.

ZEPHANIAH 2:4 – 15—JUDGMENT ON THE NATIONS

The judgment oracle in Zephaniah 2:4 – 15 covers the four points on the compass—Philistia to the west (2:4 – 7), Moab and Ammon to the east (2:8 – 11), and then the two most powerful nations in the region, Cush to the south (2:12), and Assyria to the north (2:13 – 15). The connection between Cush and Assyria is important. The final defeat of the Cushites by the Assyrians and the accompanying destruction of the Cushite power center in the Egyptian city of Thebes in 663 BC marked the height of Assyrian expansion. Ironically, as mentioned above, this event also marked the beginning of the downfall of Assyria, for Yahweh proclaims judgment on the Assyrians for such violence.1

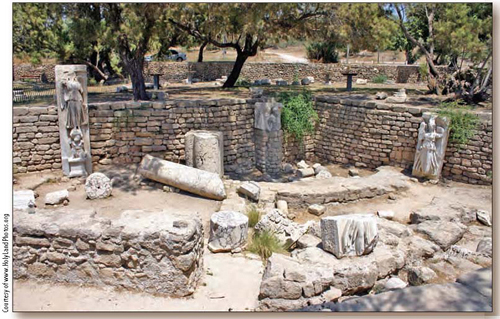

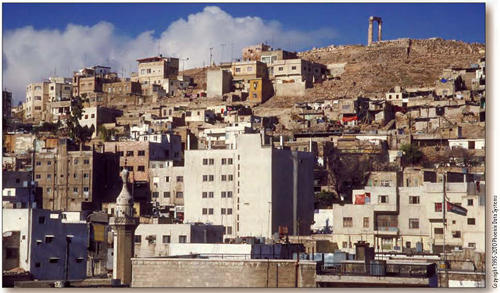

The citadel of Rabbah Ammon, capital of the Ammonites, was located on this hill, now in the middle of modern Amman, capital of Jordan. Several of the prophets prophesied judgment on the Ammonites.

The NIV translates Zephaniah 2:12 as follows: “You too, O Cushites, will be slain by my sword.” What is puzzling about this translation is that the expansion in the following verses (2:13 – 15) pronounces judgment quite clearly on Assyria, not Cush. The solution to this puzzle lies in the questionable translation that the NIV follows in this verse. There is no future tense verb (imperfect) in the Hebrew of 2:12, but only a verbless clause with a pronoun (even though there are numerous imperfect verbs in the verses that follow dealing with the judgment on the Assyrians). Literally, then, Zephaniah 2:12 would read: “You also, O Cushites; slain of my sword are they.” Grammatically and contextually, it is probably preferable to translate and understand 2:12 as a current statement of fact, describing the Assyrian sack and devastation of Thebes in 663 BC, rather than a prophecy of coming judgment.2

Thus, as in Isaiah, the Cushites as an imperial Gentile power that did not acknowledge Yahweh fell under the same judgment of Yahweh that the other powers experienced. Yahweh judged Cush through the Assyrians, whom he had raised up. But then Yahweh likewise used that action by the Assyrians as the basis for pronouncing and predicting judgment on the Assyrian empire as well.

ZEPHANIAH 3:1 – 8—JUDGMENT ON JERUSALEM

In Zephaniah 3:1 – 8 Yahweh returns to proclaiming judgment on Jerusalem. The stress of this unit is that Jerusalem will not accept any discipline or correction from anyone, including Yahweh, even in spite of Yahweh’s judgment on the nations (3:6) and his faithfulness to Israel throughout the years (3:5). Like Jeremiah, Zephaniah lists as the culprits the very leaders of Jerusalem—nobility/officials, false prophets, and priests (3:3 – 4). At the end of this unit, however, Zephaniah confronts the faithful (probably the same group called humble and obedient in 2:3) with an exhortation to “wait” (in faith) for the day of Yahweh to come. This is similar to Habakkuk’s conclusion, “Yet I will wait patiently for the day of calamity” (Hab. 3:16).

ZEPHANIAH 3:9 – 13—RESTORATION OF JERUSALEM AND THE NATIONS

The nation of Cush reappears for the third time in Zephaniah 3:9 – 10, in a passage describing the future ingathering of Yahweh’s people:

Then will I purify the lips of the peoples, that all of them may call on the name of Yahweh and serve him shoulder to shoulder. From beyond the rivers of Cush my worshipers, my scattered people, will bring me offerings (Zeph. 3:9 – 10).

Following a typical pattern in the prophets, Zephaniah shifts from proclaiming destruction to prophesying restoration. Just as he had been announcing destruction on both Jerusalem and on the nations, he now declares restoration for both groups. In 3:9 – 10 Zephaniah delivers a promise of salvation for all the peoples of the earth. Then in 3:11 – 13 he briefly describes salvation for the people of Israel. Interestingly, 3:9 – 10 contains numerous allusions and connections to the Tower of Babel story in Genesis 11.

Just as the languages (lit. “lips”) of the peoples are confused in Genesis 11, so the “lips” are purified in Zephaniah 3:9. The implication is that the effects of the Tower of Babel are being reversed. In a similar fashion, Zephaniah refers to “my scattered people” (lit. “daughter of my scattering”), perhaps an allusion to the scattered people in Genesis 11, where the judgment of Yahweh brought about the breakdown and destruction of international order (resulting in the scattered situation of Genesis 10). In contrast, Zephaniah paints a future picture of salvation, depicting a dramatic restructuring of the entire world order (alliances, enemies, etc.) in which the nations and Judah join together to worship Yahweh. To typify those foreign nations that stream to worship Yahweh, Zephaniah refers to the area “beyond the rivers of Cush” (3:10), a clear reference to the African kingdom of Cush and the southern regions beyond. In a role similar to that which Ebedmelech plays in the book of Jeremiah, the Cushites in the book of Zephaniah are depicted as a paradigm representing the inclusion of the nations (Gentiles) into the people of God.

Throughout the Old Testament the nations enter into the covenant or the “people of God” in two different ways. The first way is historical, as individual foreigners (like Ruth, Rahab, E bedmelech, etc.) become part of Israel/Judah through faith, intermarriage, naming, and so forth. The other avenue of entrance into the people of God is eschatological. As we have seen throughout the prophets, Yahweh points to a glorious time in the future when the nations will join his people in worshipping him. The short book of Zephaniah includes both aspects, focusing on the foreign Cushites as the paradigm. The first aspect is seen through Zephaniah’s physical father named Cushi, introduced in the opening verse of the book, and the second a spect is revealed through his typical prophetic picture of the great restoration, when Yahweh gathers together all peoples, even those from beyond the rivers of Cush.3

ZEPHANIAH 3:14 – 20—REJOICING IN YAHWEH’S SALVATION

The final unit in Zephaniah ends on a positive note. One feature of the day of Yahweh is that at that time Yahweh will bless both Jerusalem and the nations. Yahweh will restore his scattered people and reside with them as King of Israel (3:15). Part of the punishment of Israel/Judah was the loss of Yahweh’s presence, but in the deliverance of 3:15–17, Yahweh declares that he will be with them to protect them and save them.

Zion (Jerusalem) is thus called upon to rejoice at this future promise (3:14). This salvation is so spectacular that Yahweh himself joins in the happy singing (3:17).

Thus Zephaniah ends with a wonderful picture of restoration. Yahweh is reigning as king, having subdued all enemies. There is no longer any reason to be afraid, and all oppression has been ended. His people are rejoicing in the streets in celebration, and Yahweh himself, in loving care, so delights in his people that he breaks out in joyous singing as well.

» FURTHER READING «

Bruckner, James. Jonah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah. NIV Application Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2004.

Floyd, Michael H. Minor Prophets, Part 2. The Forms of the Old Testament Literature. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000.

Hays, J. Daniel. From Every People and Nation: A Biblical Theology of Race. New Studies in Biblical Theology. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2003.

Robertson, O. Palmer. The Books of Nahum, Habakkuk and Zephaniah. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1990.

Smith, Ralph L. Micah-Malachi. Word Biblical Commentary. Waco, TX: Word Books, 1984.

» DISCUSSION QUESTIONS «

1. Zephaniah 3:17 states of Yahweh that “he will rejoice over you with singing.” First discuss the context and meaning of 3:17. Then discuss whether the reference to the singing of Yahweh is literal or figurative. That is, does God really sing? Give reasons for your answer.

2. Both Isaiah and Zephaniah portray the Cushites (Black Africans) as part of the Gentile inclusion that becomes the people of God. Likewise, it appears that Zephaniah’s father was connected in some way to Cush. How does this affect our theology regarding race?

» WRITING ASSIGNMENTS «

1. In the context of Zephaniah 2:3, discuss the relationship between humility, obedience, and righteousness. Also, how does this verse relate to Habakkuk 2:4 – 5?

2. Explain the difference in how amillennialists and premillennialists would interpret the fulfillment of Zephaniah 3:14 – 20.

11. Michael Floyd, Minor Prophets, Part 2, The Forms of the Old Testament Literature (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), 212–13.

2Hays, From Every People and Nation, 127 – 28; Floyd, Minor Prophets, 212 – 13.

3Hays, From Every People and Nation, 129 – 30.