And if it is good to be recognized, it is better to be welcomed, precisely because this is something we can neither earn nor deserve.

—Hannah Arendt (1969, Speech to American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1)

Performances at folk festivals have long encouraged community members to engage in imaginary travel, drawing attention to the tension between us/ them, here/there, and then/now, while also collapsing these divides (Bauman and Sawin 1991; Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1991). Growing out of colonial discourses of the eighteenth century, they implicitly address questions such as: what does “foreign” or “foreigner” mean? Where is home? Or, who are strangers or aliens? In this way, festivals like the Festival of Nations have always broadly involved “struggles for recognition.” These struggles center around how people make cultural, political, or social claims that involve gaining equal respect for diverse identities within a pluralistic society. Moreover, these struggles for recognition are most often grounded in concepts of justice that place a strong emphasis on mutual dignity and appreciation.

Through folk performances in festival contexts, ethnic groups hope to gain positive recognition for what their heritage has contributed to the “American tapestry.” Implicitly, their involvement also addresses concerns about the social outcome of continuous “misrepresentation.” As Charles Taylor argued, “Our identity is partially shaped by recognition or its absence, often by misrecognition of others, and so a person or group of people can suffer real damage, real distortion, if the people or society mirror back to them a confining or demeaning or contemptible picture of themselves. Nonrecognition or misrecognition can inflict harm, can be a form of oppression, imprisoning someone in a false, distorted, and reduced mode of being” (Taylor 1992, 25). Within community festival contexts, the question becomes: “are ‘we’ fellow community members, or, are ‘we’ alien to one another?”

Festival of Nations banner. Author photo.

Scholars studying such struggles for recognition have typically focused upon discourses that can be seen in courtrooms, mass media, cultural centers, political speeches, and school curriculum that celebrate the traditional dress, food, art, and local histories of students (Bingham 2006, 327–28). I believe this emphasis upon discourses of social justice and recognition has overshadowed how cultural performances, characterized by rhetorical claims for acknowledgment, may facilitate an ethic of care. These performances, I argue, must be attended to as we parse out the tensions between recognition and acknowledgment that I have outlined in chapter 1.

To explore these issues, I focus on women’s folk performances at an “India” culture booth at the Festival of Nations in 2000. This booth, designed to replicate an idealized “village home” was created by members of the School for Indian Languages and Cultures, a grassroots nonprofit ethnic school that provides secular education about India and its diverse multicultural population. My understanding of the performances at this event grows from nearly two years of fieldwork with SILC that included participant-observation, interviews, formal and informal interviews, surveys, and archival research at the Minnesota Historical Society and the International Institute of Minnesota.

The Festival of Nations offers a myriad of folk demonstrations, from African American doll making to Iranian rug weaving. It is a rich fieldsite that has provided me opportunities in the past to think and write about issues of immigration and ethnicity and engage with scholarly critiques of multiculturalism in festival contexts. I have also interpreted performances at this site through a postcolonial feminist critique, focusing on the ways that women have often been constructed through ideas of family and home, within Indian nationalist discourses (Garlough 2011). In this chapter, however, I revisit this site to reflect upon a previously unexplored question. Through the enactment of women’s folk art, how did SILC’s “village home” emerge as a women’s performative space that facilitated acknowledgment?1 I argue that through spontaneous conversations within this gendered space, an invitation for meaningful interaction emerged. This playful discourse—fueled by the dynamic interactions between audience members and performers—allowed for the performers to strategically represent themselves in ways that transgressed the essentialized representations of “ethnic people” that festival goers have come to expect. Instead, the booth drew together a diverse group of women who offered personal narratives that provided a more complex understanding of the opportunities and challenges facing Indian American women as “tradition keepers” in their communities. Audience members responded to these more complex representations in ways that exceeded intellectual recognition; instead, they engaged in public acts of acknowledgment that took special notice of the performers, their personal narratives, and the folk practices that were shared.

I believe that it was not serendipity that this women’s performative space facilitated the potential for acknowledgment; indeed, the Festival of Nations was designed, from the very first, to create occasions for such social intervention. The brainchild of Alice Sickels—a progressive community advocate for immigrants in the 1930s, social critic, and the first director of the International Institute of Minnesota—the festival was never meant to be simply entertaining or merely informative of Midwestern immigrant culture. Responding to the twentieth-century “Americanization” movement (an effort by both government agencies and private citizen organizations to coerce immigrants into adopting the English language and abandoning the cultural practices of “foreign places”), Alice envisioned the Festival of Nations as a means to counter prejudice against immigrants and advocate pluralism within American culture. In the process, she argued something quite innovative: in the public sphere, meaningful recognition often begins with practices of “acknowledgment” (Sickels 1945, 183–84).

In taking this perspective, Alice’s progressive notions about the role of acknowledgment in folk festivals and the political ends they might accomplish seem to foreshadow the very arguments Fiona Robinson and Selma Sevenhuijsen (as described in chapter 1) advanced regarding the importance of establishing caring relations “with not so distant others” (Robinson 1999; Sevenhuijsen 1998). Within the Festival of Nations context, Alice hoped that preparations for the performances at the cultural booths might inspire conversation among diverse ethnic participants that would act as rehearsals for democratic discussion in the public sphere. Interestingly, from its inception in 1932, women played a prominent role in this effort. According to Festival of Nations records and Alice’s writings, activities were primarily managed by local women who organized and inspired people in their communities to design and construct exhibits, donate local folk items to display, sew ethnic clothing, choreograph dances, and cook traditional foods. Women from different communities—initially strangers to one another—would spend the days leading up to the festival helping one another to set up booths and to prepare the event arena for audiences. In the process, they engaged in conversation, gained knowledge about one another’s cultural traditions, and made friendships that transcended the festival boundaries and overflowed into everyday life.

Alice also hoped this “ethic of care” that characterized the preparation for the festival would then manifest in the performance context as well, as ethnic performers interacted with festival audiences and engaged in rhetorical acts of acknowledgment (Sickels 1945). This chapter considers the possibility that even within today’s more complicated performance setting, Alice’s commitment to the rhetorical potential of acknowledgment might still effectively facilitate community work toward liberal democratic goals. This exploration begins with a discussion of two specific ethnographic sites: the School of Indian Languages and Cultures and their work at the Festival of Nations.

SILC, a “Saturday only” ethnic school, was founded by five women—Neena Gada, Usha Kumar, Rita Mustaphi, Rujuta Pathre, and Prabha Nair—in 1979. An offshoot of the Bharat School, established in the late 1970s by K. P. S. Menon, these women designed SILC to be a non-for-profit grassroots community project. This volunteer organization immediately caught my attention because of its reputation in the South Asian American community as an unusually progressive place for young people to learn about South Asian history, language, folklore, and classical culture. Ethnic schools have a distinguished history in American cultural life. Since the early colonial period, these schools have played a vital role in ethnic community creation and maintenance, communicating a group’s conscious perception of itself and providing a cultural legacy to be given to subsequent generations (Mohl 1981). As Joshua A. Fishman notes, “we’re dealing with an old and deservedly proud American tradition in education … the ethnic community school is American from the very beginning of the country and a constant theme in the history” (1980, 10). Yet, aside from the pioneering study conducted by the American Folklife Center in 1982, very little research has been done to explore the role these schools play in constituting identities for participants or the importance of community-based ethnic schools in helping the United States retain its multicultural profile. To some, it may seem unlikely that these schools have remained a permanent part of our educational landscape. In the past when immigrant neighborhoods disintegrated, ethnic schools often were disbanded as well; however, today it seems that they do not disappear easily. In fact, modern advances in transportation and communication technology—like the Internet—seem to be facilitating the development of these institutions, despite the challenges of grassroots organizing. Indeed, as ethnic communities continue to grow and coalesce, voluntary organizing efforts and grassroots subsistence for these institutions have intensified. Like most forms of grassroots social action, these ethnic schools arise when an underprivileged section of the local population becomes organized around specific issues and demands a more equitable distribution of power or resources for decision making. As Neena, a former SILC principal stated, “In other parts of the USA, many Indian provincial language and culture groups had been started and are working well toward limited objectives. However, we felt the need for an organization which can maintain an overall Indian cultural identity through the strength of our regional languages and cultures.”2

In comparison to many language or culture schools for Indians in America it was envisioned as a progressive grassroots organization that would support the needs of South Asian American kids and parents from diverse social classes and regions, from Gujarat to Kerala. For SILC volunteers, this commitment goes beyond mere multiculturalism. Rather, its secular orientation speaks to a commitment to keeping the heterogeneity of their Indian American community visible and active. Consequently, SILC is open to all people, regardless of race, religion, or ethnicity and, as such, it provides a unique space in which to voice opinions, impart values, and teach cultural practices. It is not only a space of care where I saw examples of teachers interacting with students patiently, attentively, and empathetically. It is also an enclave in which community members can informally discuss frustrations and deliberate upon issues and exigencies within the local South Asian American community, mainstream America, or international contexts. Students here are enabled to develop a multicultural voice through which they can express their lived experience (Darder 1991).

The School for Indian Languages and Cultures is located in Minnesota, a state known more for its German, French, Norwegian, Swedish, or even Ukrainian immigrant communities. Indeed, for many people, Minnesota still epitomizes the culturally homogeneous or “white” agricultural interior of the United States, despite sizable diasporic movements of Mexican and Hmong individuals, and indigenous populations of Native Americans. The first substantial group of Indians in Minnesota did not arrive until the 1950s—primarily a group of professors, scientists, and graduate students enrolled at the University of Minnesota. Indeed, the bulk of the Minneapolis Indian immigrant community was created primarily as a consequence of the brain-drain 1965 immigration legislation.3 Like many of the larger South Asian communities in the United States located in urban centers, such as New York, Chicago, Houston, or San Francisco, the Twin Cities community began as a small and regionally diverse group. As Neena Gada has commented, “Actually, for quite a few years it was just ‘you were Indian’; you weren’t Gujarati or Marathi and there weren’t that many people. And in those days we did a lot of dinner parties, because people were homesick, so you would have dinner parties. And you were walking in the shopping center and you see someone from India, you will just go up to that person and say hi and introduce yourself and get their name and exchange telephone numbers and have them to the next party you have. Because there weren’t that many people so everybody sought out everybody else.”4 However, today the cities contain plentiful Indian regional concentrations and is heterogeneous in terms of religious and ethnic traditions, as well as social class, education, occupation, and linguistic groupings.

I began my fieldwork at the School for Indian Languages and Cultures on a chilly Saturday morning in the fall of 1997. As I walked up the sidewalk to Como Park High School, I watched groups of South Asian American parents, teachers, and students make their way into the main hallway and heard Preeti—SILC’s principal—ringing her handbell to signal the beginning of the school day. I wondered to myself, as I heard the general assembly of students singing “Jana Gana Mana,” “Vande Mataram,” and then the “Star Spangled Banner,” how, I could balance the roles I hoped to play at this site.

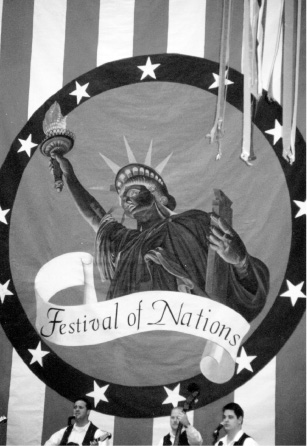

Garlough and husband at an SILC dinner event. Author photo.

A month before, I had met Preeti for the first time in the hopes of gaining permission to do ethnographic research at SILC. At the time, I was not sure how she would react to my proposal to participate in more than one capacity. First, as a scholar, I was interested in understanding how this grassroots ethnic school had developed within the broader context of the Minnesota South Asian American community. On first glance, it seemed to me to be unique in comparison to the rest of the South Asian American schools in the area that featured a rigorous religious or specifically regional emphasis. In particular, I was curious about the educational philosophy that fueled their mission and the grassroots volunteers whose efforts drove the activities. I wondered how this school might support members of the South Asian American communities by connecting local, global, and transnational concerns. In addition, I wondered whether this school and their performances, operating from outside of mainstream educational institutions, was part of broader grassroots struggles for recognition and justice. These concerns grew from my experiences as a teacher in alternative educational contexts, as well as my interest in the work of educational theorists such as Paolo Freiere and John Dewey. My research methods, I told Preeti, would be ethnographic—including formal and informal interviews, focus groups, surveys, and participant-observation in various classrooms and the school cafeteria. While I would schedule times for longer, more private conversations, there was much to be learned by simply “hanging out” in the hallway between classes with students and listening to them talk about their lives or chatting with the parents at a lunchroom table while they waited for their children. Indeed, I knew that from the earliest days of SILC, the “waiting area” for parents had been an important and vibrant site for interpersonal community building.

By frequently being available and open to conversations in these spaces, I hoped that, over time, a trust would develop between myself and the SILC members, our talk would deepen, and I would begin to understand how individuals within this context struggled and strategized with the cultural traditions that connected them and the interests that divided them. I wanted to get past the polite formalities that often characterize the early months of forming relationships and learn about their struggles as well as their successes. And, in the process, I wanted to share my own struggles and successes, so that something more than a “working relationship” might develop.

Given this desire, the second request was somewhat easier to ask of Preeti, yet harder for me to imagine carrying out. As a first-time parent, and the mother of a biracial child of Indian American origins, I was hoping to participate in SILC as a parent as well. Gabe, my first child, was growing up far away from grandparents, aunties, uncles, cousins, and friends who could help us to raise him within a rich set of Indian—specifically Gujarati—family traditions. As a small family unit of three, we were finding it difficult to create the everyday context for living through and within the Indian American culture we wanted Gabe to experience. Nevertheless, I also felt uneasy about bringing Gabe, afraid that it might compromise my role as a researcher. That is, ironically, I was concerned about being misrecognized as simply a parent and not as a professional as well. Preeti, who was herself pursuing a graduate degree and had children attending SILC, offered good advice about how to balance roles within the SILC content and was enthusiastic about Gabe attending. Indeed, many of the women I encountered at SILC had experience with this “balancing act” and found that this space provided not simply a site for student learning but also a valuable support system for parents’ care-giving responsibilities. As Preeti has noted, “I feel like my ‘Indianness’ is something like a springboard from which I have to feel my sense, my place in this world. You can’t deny your heritage, so SILC allowed me to embrace my Indian heritage. It kind of affirmed it, and it helped me with raising my kids. Like when I had my daughter’s graduation. I had a big board with pictures of all the friends who helped me raise her. You know, I said, ‘It takes a village to raise a kid’ and to me, SILC in some ways, was a village really. I felt it strongly.”5

Gabriel and friends at SILC. Author photo.

And to my surprise and pleasure, in responding to all my requests, Preeti also added a third role that she wanted me to play on occasion—SILC volunteer teacher. In this capacity, she asked me to lecture on the subject of folklore, substitute for her art class, assist in other classrooms, and participate on the Festival of Nations committee. Not surprisingly, over the course of time it became clear that in many ways Gabe’s weekly attendance actually helped me to do my job as a researcher. At the time, SILC did not have preschool for children his age and he was too young to attend classes. Nevertheless, Gabe bonded with the older kids, aunties, and uncles, as they helped to take care of him during class time. With the help of the teenage students, Gabe was also able to participate in school performances such as SILC Day.

Indeed, my dual roles as researcher and parent became a crucial part of how I was welcomed into this school context. It is through this lens that I began to understand the role of care in this ethnic school and the need for acknowledgment when you are initially in a position to be misrecognized in a social space.

SILC is a nonprofit grassroots project and consequently has never had its own facilities. It runs entirely on the efforts of its staff of approximately thirty that is still composed exclusively of volunteers who are willing to make the significant time commitment required to attend teacher-administrative meetings, prepare curriculum, instruct class each Saturday, organize and facilitate field trips, or coordinate other extracurricular activities.6 As Preeti Mathur, SILC’s former president, wrote in the Twentieth Anniversary Commemorative Yearbook, “SILC has had and continues to draw some very dedicated volunteers who are its backbone. It is their hard work and diligence that sowed the seeds and nurtured it to where it is today. Many individuals put in countless hours and through their selfless service and enthusiasm have created an environment that has taught our students something no textbook could ever cover” (1997, 9).

The staff and students possess very diverse cultural backgrounds and there are representatives from many parts of India (Kerala, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, etc.), as well as other South Asian diasporic locations. The teachers display a range of economic levels and education, although most are middle class and college educated. However recently, as the community itself begins to diversify and highly educated first- and second-generation Indian Americans help their less educated relatives immigrate, the teachers are beginning to show a greater degree of occupational and educational diversity. This influx of new participants, recently arrived from India, has provided the school with important perspectives upon what cultural or linguistic practices are currently in vogue in India. For individuals who have immigrated thirty years or more ago, or perhaps have never lived in India for an extended period of time, this information is quite valuable.

Clearly SILC provides a “dwelling place” that supports a particular Indian American ethos—one that creates a pluralistic understanding of what it might mean to be Indian American. Thus, according to former principal Chitra, “SILC has been a bridge to connect first-generation Indian-American children to their Indian heritage. It has been a center for education and knowledge over the past twenty years. It has been a link between two worlds that are so very different” (SILC Yearbook 1997, 9). Moreover, it is a transnational venture that takes into account that many South Asians live their lives across borders and maintain their ties to home, even when their countries of origin and settlements are geographically separate.

According to many of the teachers and parents I spoke with each week, SILC’s focus upon creating an Indian American community school “unified in diversity” not only addresses the potential for regional fragmentation within the Indian American community, it also called attention to the problems resulting from fragmentation in India as well. This fragmentation, of course, is not surprising given the fact that India was composed of separate princely states prior to and during British colonization and did not become a nation until just fifty years ago. Indeed, India is still developing a sense of what it means to be “Indian.” Most individuals connect much more closely with regional or religious identities, rather than some national loyalty. Given this, it is relatively easy to understand how developing an Indian American identity might be challenging for some immigrants, particularly those in the first generation.

Consequently, during my time at SILC, I observed and participated in many performance events that address the delicate balance of the regional with the national. For example, students begin each school session by singing the American and Indian national anthems, but they also celebrate their regional Indian identities through language and cultural activities, such as regional folk dancing performances, storytelling performances that feature regional folk tales, or the regional dress pageant where students exhibit the traditional apparel from their Indian state. As Vishant, a SILC school student noted, “I think the beauty of SILC is that you go to school with kids from all around India. It is an experience that you could not easily have in India because of conflicts and tension. At SILC you work with people who come from many parts of India” (SILC Yearbook 1997, 9). Indeed, unlike other Indian American community groups I have worked with over the years, the very composition of the student body simply makes it impossible to forget the heterogeneity of India’s citizenry. Needa Gada adds, “a lot of times—at least I remember twice—two different ambassadors visited over the years. And they told us that they didn’t even think there’s something like this in India, but in the United States, wherever they visited, they have not seen an experiment of something like this happening anywhere else, under one roof, all these languages. See usually, people have a tendency to have a Gujarati school or a Marathi school or religious school but nothing like actually having all different languages under one roof. That credit really goes to Dr. Menon for coming up with the whole concept.”7

SILC’s commitment to represent the diverse regional cultures of India is also apparent in their curriculum design. While some teachers base their curriculum choices upon students’ interests, others focus upon their own areas of expertise. Over the years, offerings in languages have included Hindi, Kannada, Malaylam, and Gujarati—an impressive representation of the twenty-three languages and sixteen hundred dialects of India, especially given that many university campuses are unable to offer such a variety. In recent years, electives have included instruction on instruments like the tabla, regional Indian cooking, vocal performance, folk and classical dance, yoga, and folk art. These electives tend to focus upon “hands-on learning” that is then enriched by short lectures about the historical or cultural significance of the topic. The regular curriculum focuses upon subjects such as history, geography, philosophy, politics, literature, and popular culture.

Folk performance and narrative is also an important and embedded part of the curriculum. This, of course, is not surprising, as folklore often plays a large role in the curriculum of schools with a multicultural emphasis. Through folklore—meaning the daily expressive culture or traditional activities of a particular group of people—students learn new ways to understand the practices, performances, and material art forms they encounter in their community and homes, but often are seemingly invisible to them in their everyday lives. For instance, in some classes students read folk stories to complement their study of historical events in India. In others, students wrote plays about current social issues in the United States drawing upon Indian narratives, characters, and motifs. During my time at SILC, I was often asked to help facilitate classroom activities, from guiding the creation of folk art projects to teaching longer “special sessions” on traditional Indian folklore and storytelling practices.

For extracurricular events, like the Festival of Nations, students and teachers often mix genres, combining mythology, fables, and classical texts to create dynamic displays for mainstream audiences. As Rama Padamnashan has recalled, at one Festival of Nations, “we depicted three different scenes from three different time frames of Indian mythology. We chose the Ramayana, a scene from the Ramayana. We chose a scene from the animal fables, the Panchatantra, and we also chose a scene from the Sanskrit classical play, Shakuntala. These three depicted three different types, three different styles of legends and myths that India is quite well known for.”8

Such cultural performances were an important part of school life.9 These performances, along with the relationships they fostered, were meaningful to many of the students I spoke with each week. As Shruti Mathur wrote in the twentieth anniversary yearbook, “Attending SILC helped me know that there are other kids “like me.” I’m not the only kid whose parents won’t let them date, or who come down hard on the issue of school or other such things. My house isn’t the only house that smells like curry, pipe smoke, and incense. I’m not the only one who is ‘American’ at school and ‘Indian’ at home. Lastly, it has made me realize the fact that I don’t mind being ‘Indian at home.’ I feel like I have more than some others. I can speak and understand (to a point) two languages, I’ve tried many more foods, and seen many more places, and I can say why August 15th is an important date in Indian history. I’ve been involved at the Festival of Nations and other events since I was little, dancing or being at the exhibit booth, something most people are only experiencing now for the first time. Sure, American may be the melting pot of the world, but I still managed to come out with a little bit more spice than others do” (86).

Indeed, organizing and participating in the Indian performances at this festival takes up a significant amount of SILC teachers’ and students’ time each year; though most viewed participating in the Festival of Nations as an important opportunity, as it provides a public forum for the grassroots organization to showcase the multicultural Indian activities that the students learn each year. Moreover, it offers an opportunity to gain positive recognition not only from mainstream Americans, but also from fellow members of the Indian American community with whom they may want to coalition-build. Appreciation for these opportunities is often tempered by caution, as the process of creating these emblematic performances and texts is fraught with potentially problematic issues of representation about the histories of India and Indian American communities, as well as rhetorical constraints and exigencies of festival events.

During my fieldwork at SILC, I was asked to serve on the Festival of Nations committee and help to design a booth around the theme on “Indian Temple Art,” and this opportunity gave me unique insight into the process, from beginning to end. To be sure, this was no small task. The process began with meetings to discuss the festival theme, design architectural plans, and buy building supplies. In addition, people gathered props for the booth. Neena Gada has remembered, “this was my chance to educate people … half of my things in my house were used in all these kinds of Festival of Nations exhibitions and things. We didn’t spend money in those days, you know, because we couldn’t afford it, so we used what we had or borrowed from someone we knew.”10 In this process, many different, and sometimes opposing, concerns are weighed. How should “India” be represented? What is “Indian folklore?” What will be aesthetically pleasing and intellectually interesting to a diverse group of audience members? What performances and practices will best showcase Indian folk culture? In the next phase of the process, I was sent along with another SILC teacher to a meeting the Festival of Nations sponsored for participants. Here, they outlined the policies and procedures of the festival. Finally, as the days before the event unfolded, a group assembled to physically build the booth, decorate it, and set up whatever was necessary for the cultural performance.

1998 SILC Festival of Nations booth on “Temple Art.” Author photo.

This experience of helping to plan a cultural booth for the Festival of Nations was such an interesting one for me during my fieldwork that I made a decision to return to this site each year. In 2000, I moved from St. Paul to Madison, but came back regularly to visit friends. That same year I decided to make a trip to attend the SILC Festival of Nations, an event that took place from Thursday, May 4, to Sunday, May 7. That weekend, as I entered the Saint Paul River Center amid throngs of other visitors the mood was festive. Folk music played by a small Scandinavian band wafted through the air and crowds of people consulted their guidebooks to decide what they wanted to experience first. Some wanted to visit the Hall of Flags, while others chose to participate in folk art demonstrations or buy items at the folk bazaar. Newly immigrated families seemed interested in the flag ceremony or naturalization ceremony for new citizens. Still others wanted to attend free mini-language classes offered by the International Institute Education Department.

In the liminal space and time of the Festival of Nations, visitors encountered cultural displays that playfully mimicked the experience of tourism. “Learning guides” led hundreds of tour groups through halls of cultural exhibits, explained ethnic performances, and facilitated “treasure hunts” for the adventurous. Many of the visitors who attended the event also carried an “interactive passport” to be stamped at the cultural booths. In keeping with this theme, the festival brochure replicated the form of a travel destination pamphlet, promising that on their “trip” participants would enjoy folk art demonstrations where “ethnic artisans demonstrate unique skills passed down from generation to generation,” cafes with “a whole world of tantalizing ethnic foods available for purchase,” and an ethnic bazaar in which “unique items for your home, yourself, or someone special” can be found.

Ethnic booths. Author photo.

As I slowly made my through the crowds, I was immediately struck by the enormous red, white, and blue banner in the main hall. On it, Lady Liberty—wrapped in a “Festival of Nations” scroll—looked down at the throngs of people. This piece of visual rhetoric served multiple purposes that included reminding visitors about America’s history as “a country of immigrants” to constructing contemporary civic attitudes about immigration and democracy. The banner also enacted a constitutive function—evoking positive feelings of “oneness” before visitors were challenged by the “diversity” the ethnic groups represented. That is, the artwork interpolated the audience—a body of strangers—into citizens who together constitute a nation.

While the other visitors mulled over their festival choices, some gave in to the smells of the cafe and feasted on Native American fry bread, Armenian baklava, and Filipino lumpia or Indian chicken curry, tandoori chicken, rice pilaf, chole, salad, samosa, papad, and mango shakes.

Cafe. Author photo.

Meanwhile, on the cafe stage, audiences were entertained by a continuous stream of vocal performers, from French Canadian singers, a Mexican Mariachi band, and a Polish choir. Not far away, dancers, storytellers, and musicians in the huge village square held the attention of hundreds of visitors.

According to International Institute of Minnesota records, the first “East Indian” group to perform at the Festival of Nations was in 1961 (Festival archival material). By 1964, records reveal the presence of an Indian food booth in the International Cafe. Over time, the “East Indians” expanded their involvement to include performances and a cultural booth. Later, in the mid-1970s, the Bharat School (renamed the School for Indian Languages and Cultures) began their work at the festival at the behest of local Indian Association of Minnesota leaders. In past years, SILC booths had featured “Cuisine of India,” “Indian Weddings,” “The Festival of Lights,” “Textiles of India,” and “Storytelling in India—Myths and Legends,” to name but a few. These booths tend to be one of the most popular attractions perhaps because, as Kirshenblatt-Gimblett (1991) explains: “Public and spectacular, festivals have the potential advantage of offering in a concentrated form and at a designated time and place what the tourist would otherwise search out in the diffuseness of everyday life, with no guarantee of ever finding it” (418). While visitors appear to appreciate this immediacy, many critics of festivals have rightly cautioned people to remember that these performances of everyday experience, in stories, dance, music, art, and food, are just that—performances. Here, the mundane is reimagined so that everyday use is sacrificed for a choreographed audience aesthetic; one that has dramatic form and emotional attraction. In this process, these performances often make implicit reference to social assumptions, values, and culturally appropriate behaviors. Moreover, as many cultural critics have noted, the cultural performances and exhibitions also perform problematic claims of authenticity related to gender, national, or ethnic identity (Prashad 2001).

The 2012 SILC booth was positioned near other national booths featuring folk art demonstrations such as Hmong needlework, Iranian rug weaving, Scandinavian folk carving, or African American doll making. The festival theme was “Seasons of Childhood” and in accordance, SILC’s booth centered around recreating an idealized “family moment” within the red-brick courtyard of an Indian village home. Volunteers, performing as family members, appeared to be sitting underneath a grass roof or in doorways outlined with green, red, yellow, and white triangular shapes. With the use of various puja items, from a kalash, to dharapatras, to devos, the performers enacted or explained aspects of traditional folk and Vedic “childhood” rituals drawn from the Vedas.

Not surprisingly, these performances, by and large, upheld traditional gender roles evoking a history of gendered Indian nationalist rhetoric regarding the family home as the site of India’s authentic identity. At the same time, it attempted to also point toward how “home” transcends place and time; how it is understood as a potential site of care and hospitality for humanity. For example, the performers played out aspects of the Grihya Sutras that celebrate significant milestones in a man’s life. Out of forty sacraments, SILC chose to highlight only five related to childhood: Jata Karman (Birth ceremony), Nama Karanam (Naming the baby), Anna Prasham (First feeding of solid food), Moondan/Chuda Karanam (Tonsure of hair ceremony), and Vidyarambham (Commencement of education). These performances often made appeals to “tradition” or an idealized sense of the past. This was, to my mind, an odd choice for SILC, which emphasized a secular, Gandhian approach in representing India in the classroom. To select such a decidedly Hindu set of sacraments, and to focus on formal religious practices, seemed both potentially exclusionary and overly prescribed.

The SILC booth for the 2000 Festival of Nations. Author photo.

In contrast, it was the smaller, more intimate performances that typified the principles and precepts of SILC. These everyday folk performances made the “home” come alive for audiences, and were traditionally performed by women. Sheela, who gave a demonstration of how to create a rangoli—a powered floor painting—provides an excellent example of this type of women’s folk performance. Her performance, embedded within her personal narrative of creating rangoli in both India and U.S. contexts, presented her audience with more than one set of critical discourses regarding gender norms in India and the diaspora. In addition, through conversations with audience members that were interwoven throughout her rangoli performance, Sheela contested the potentially atemporal or homogenizing discourses of the festival by engaging people in a playful exchange that sought acknowledgment within a context of difference.

A finished rangoli. Author photo.

So, what is rangoli and why is it typically a women’s folk art form? Rangoli, a type of ground rice or stone sand painting, is a popular women’s folk practice in India. Performed by women during festivals, auspicious occasions, or as an everyday ceremonial activity, rangoli is a means by which to beautify and welcome guests and deities into the home (Huyler 1994). In a culture where guests and visitors hold a special place, rangoli is an expression of hospitality and understood as an invitation, a gift, and a traditional form of greeting that brings good luck to the house. To say that rangoli is a hereditary folk art means that it is learned without any formal training. Rather, rangoli designs are often passed down through generations of women, with some designs hundreds of years old. While these are sometimes drawn with attention to traditionalism, other times they are the basis of innovative contemporary patterns. For example, today in India one can even find “rangoli groups” who engage in grassroots activism by creating designs that call attention to social and political issues and displaying them in public exhibitions.

In some ways bearing a resemblance to hex signs on Pennsylvania Dutch barns, rangolis are a means of protecting the home from ill will and caring for those who dwell within it; this includes the union of man and wife, their fertility, the nurturing of children, and family relationships. Households, it is understood, do not always remain in balance. There are many dangers to guard against, including natural disasters, accidents, violence, disease, and the malice of others. Through rangolis and pujas, women are in charge of acknowledging, invoking, and honoring the manifestation of the goddess and, in the process, caring for those they love (Huyler 1994, 15). In doing so, the designs do more than beautify; they pay tribute and perform visual prayers to secure blessings. In addition, as I learned during my fieldwork in Gujarat, women often use rangoli in celebrations of important occasions. This could include holy festivals for particular gods and goddesses, astrological phases, or seasonal rituals that accompany the first rain or planting of crops. It also is done to pay special attention to notable events in families, such as birth, puberty, marriage, pregnancy, death, or the arrival of a special guest (Huyler 1994, 15).

As Huyler notes, “Until recently in India, folk art was considered inferior, hardly worthy of mention when compared to classical urban or royal art. Because these wall and floor decorations were created in the domestic sphere by women rather than professional craftsmen, they were, for the most part, ignored. However, it is clear that they serve an important purpose in the social and cultural contexts in which they are found” (Huyler 1994, 15). Rangolis not only link mother and daughters, they link together women of past generations in every kind of family, community, and class. They also connect women from diverse religions and castes, for “although it originated as a Hindu custom, the practice … is now popular among Christians and Muslims” (Huyler 1994, 164). If rangoli is performed as a daily activity, as it often is in eastern and southern India, women begin early in the morning, typically taking about thirty minutes in the process. In contrast, during important festivals, rangoli can take about an hour. Each rangoli painting is unique. Each region and group of communities has its own artistic style and each household creates its own innovations. Using finely ground powder, women create floor and wall designs that feature geometric figures with lines, dots, squares, circles, triangles, or swastikas. Within these patterns no line should be broken, as it may allow evil to enter. Sometimes these designs take on a three-dimensional form by shading the traditional two-dimensional designs. Often motifs featured are taken from nature, such as mangos, peacocks, elephants, sun, moon, trees, the sea, or flowers.

Traditionally, the colors for the designs are made from natural dyes, barks of trees, or vegetables. Today, however, bright synthetic colored powders are the norm. This colored powder is usually applied freehand by letting it run from the gap formed by pinching the thumb and forefinger. If the rice powder is used to craft the images, it is considered particularly auspicious because the substance sustains the lives of birds and insects. In addition, powder can be made from sand, crushed bricks, or marble dust that is dyed naturally using leaves or bark. Similar to Buddhist and Hindu mandalas, using powder or sand as a medium for creating rangoli is sometimes thought to symbolize the fragility or transient nature of life in that they do not last. “The designs are smudged as the sun rises and people move in and out of the house. Within an hour or two no trace of them remains. It is the moment of creation, the intent of the heart, that is important. Art, like life, is considered transitory. Swept away each day, the paintings are newly created before the following dawn … as they have been for centuries” (Huyler 1994, 14–15).

Sheela entered the “stage” for her rangoli performance dressed in a royal blue and gold-trimmed sari. Her gold bangles and earrings shimmered in the stark lighting as she sat on the floor of the “village home.” Her elegant and traditional dress stood in contrast to other Indian Americans gathering around the performance space in casual clothes like jeans and T-shirts. Indeed, her appearance had much more in common with the girls from SILC who had come to folk dance in the arena and were waiting with their parents near the culture booth.

Sheela, glancing at the crowds, the idealized culture booth, and the other ethnic exhibits, paused for a moment and then smiled while shaking her head. Her bemusement at the festival context seemed to have much to do with her hesitation about representing herself as some sort of ideal, “traditional” Indian woman. It raised difficult questions about what “being Indian” in an “authentic” sense even means. Consequently, in this gap between the ideal and the real, she began to construct a space of contestation by articulating cultural difference in a more complicated way.

On the floor of the “village home,” she began by carefully laying out the materials for her design, brightly colored finely ground powder in zippered baggies. Using her fingers to pinch the powder, she began to sketch the outline of a star. With a delicate touch, she placed a single dot in the middle and then drew lotus petals around the points of the star. Slowly, curling vines were drawn from the lotus flower petals. This woman, on the floor of an imaginary home, enacted an artistic practice that she had done a hundred times before. Her performance called attention to echoes of the past, while also addressing the specific context of the festival.

As the design emerged, three older Indian American women and one Indian woman standing to the side of the booth began to comment on the quality of the powder and the choice of design, while sharing some of their own life experiences with rangoli in the process. One of the women spoke extensively about how hard it is to get good materials here and what you might have to substitute. I turned to speak with them about how my aunties had brought me a rangoli-making set from Vadodara a few years prior.

Meanwhile, the circle around Sheela was now growing larger and tighter. A group of young local schoolgirls made their way to the front and sat on the ground next to her. Next to me, an Indian American woman began to describe to her daughter the artful and complex designs her mother used to make during Diwali festivals in their village. Overhearing this conversation, one SILC teacher turned to her and described a few of the intricate rangoli designs she had seen her cousin create at weddings that featured flower petals and devos. I chimed in that I knew a woman who had immigrated to Kenya from India two generations before and she often used these embellishments as well.

Two African American women joined in and began to compare their experiences of designing quilting squares within their own communities to Indian rangoli patterns, remembering family designs and the women’s culture that surrounded this folk practice. The other audience members outside of the main circle (both men and women) seemed interested in listening to these various conversations unfolding around the performance. It was a moment, out of many fieldwork moments, that I will never forget. Slowly, and without conscious intent, a women’s space had been created. These personal narratives drew lines of connection back through generations and across the globe—connecting the diverse group of women in ways that had not been visible moments before. Moreover, through this sense of presence, this group of women had become more than mere spectators. In lingering with one another and engaging in these small interpersonal acts, they enacted an ethic of care within this public space. And it is just these types of small acts that Sickels, Sevenhuijsen, and Noddings all believe are at the center of love for our neighbor.

Throughout the performance, Sheela glanced up to share information with various audience members, reflecting upon her own experiences of doing rangoli in the United States as opposed to India, as well as regional, local, and ethnic variations in rangoli art from Gujarat to Kerala. In response, another Indian American woman began to tell the story of a relative who had made a rangoli design on her front doorstep in America that featured the religious image of a Hindu swastika, only to be told later that a neighbor thought she was invoking Nazi symbolism. Sheela agreed that cultural awareness about such issues was always an important issue in public spaces and self-reflexively called the audience’s attention to the context in which she was performing and the constraints of her performance.

In doing so, she began breaking down the boundaries between herself and her audience, as their questions and stories played off one another, creating a more dynamic sense of the women’s practices being represented in the booth. It became clear that rangoli was an important part of everyday women’s history, a craft that required artistic expertise, cultural competence, and local sensitivity. The narratives that these women offered showed the ways women’s folk practice are integral to daily life—one that honored women, their relationships, their labor, and their communities. These narratives put this gendered perspective at the center of this booth’s performance and took into account the ways gender and kinship identities are implicated in these practices.

As Sheela spoke, she filled in the petals of her design with purple, pink, gold, blue, and green powder. Children and adults alike began to suggest that more colors to be used, Sheela laughed and asked the audience members which materials they would like for her to use next. In the midst of this play, Sheela was intent upon drawing her audience close and creating interpersonal relationships within this festival context. In the process, she made it clear that she wasn’t performing a generic Mother, Wife, Sister, or Daughter-in law in this imaginary “Indian house.” In doing so, she sounded a call of conscience and asked for others to listen as she spoke about her life and the reasons none of these roles defined the limits of her self-understanding in this context. Rather, she used her personal narrative to encourage subtle but subversive conversations that demonstrated her subjectivity.

For example, one part of the encounter unfolded as follows:

JAN (Mother of child adopted from India): “What is your name?”

SHEELA: “I’m Sheela.” (Looking up and then continuing to draw.)

JAN (turning to her child): “That looks like mendhi done on the floor, doesn’t it?” (to Sheela) “Are the colors natural colors? That looks like turmeric.”

SHEELA: “Yes, it is turmeric.” (Looking up and happily surprised.)

JAN: “Do you usually do this outside of the door for special occasions (in India)?” (Looking at the posters hanging in the booth that explain the childhood rituals for Hindu males.)

SHEELA: (Sheela looks at the posters, too, and hesitates before replying.) “No. In my home every day we used to do. Every morning, early morning, we clean our floor outside of the front door and then we put this. Because it is a tradition for us … a family tradition. Not everyone. You know? Some in India do it and some don’t. Even some Hindus don’t.” (Long silence, looking at audience members.)

JAN: “Now, at festival time, would men and wome work on the same one?”

SHEELA: “No, at each house the women do it.”

JAN: “Do they still teach the young girls now how to do this?”

SHEELA: “Sure.”

JAN: “Do they do this in India in the big cities and not just the villages?

SHEELA: “Yes, they do it there. I do it here, too, in the U.S. You know, I do it here in the U.S. It is different but I do it here, too. I do it but most people don’t know why.” (Big burst of laughter.)

JAN: “Are there books that show you how to do this?”

SHEELA: “Oh, yes, so many books. So many designs there are. But you know …”

JAN: “Oh, so you have it in your head.” (Laughter between the two.)

SHEELA: “Yes. We don’t need books or to follow those designs (looking at the posters) … we have imagination. We can draw any designs. (Pause.) It is different.” (She begins to expand upon her drawing.)

JAN: “Sure. I know what you mean.” (Garlough 2011)

Analyzing such dialogue as “performance” has a long and prominent history in cultural studies and performance theory. Dwight Conquergood, in particular, has been influential in this area, lending insight into how conversational performances bring “self and Other” together to question, debate, and challenge one another. He felt these performances are significant because they emphasize a “living communion of felt-sensing, embodied interplay, engagement between human beings.” Within these moments, there is the potential for reciprocal giving and taking. Moreover, as Thomas Farrell astutely notes, conversations, such as this one, hold valuable rhetorical dimensions, particularly due to their situatedness within a larger public performance event (Farrell 1993). I would add that conversational performances, like the one that took place within SILC’s booth, go beyond simple acts of recognition or celebration of difference and identity politics. Rather, many functioned as rhetorical acts of acknowledgment.

In doing so, these conversations performed an ethic of care through which audience members and performers addressed the issues of others, showed mutual concern, and demonstrated attentiveness. Within the festival context, these conversations were a way of being-with-others. They were not only characterized by talk but by a deliberate listening, such that the audience created a sense of presence that was palpable. Indeed, for many scholars—including Charles Bingham, Emmanuel Levinas, John D. Caputo, and Sharon Todd—such listening is a practice that occurs before recognition (Todd in Bingham 2003, 336). Bingham argues that “listening has the potential to happen before recognition if the listener, in receiving the speech of the speaker, honors the aspects of the speech that go beyond comprehension, the aspects of speech that need not be understood completely in order to be heard … listening to another person should not be understood solely in terms of the meaning of that other person’s words … there are many times when listening is about making a communicative connection rather than understanding the other’s words themselves” (Bingham 2006, 336). In this way, listening is a form of care that manifests rhetorically as acknowledgment.

Notice, of course, that these conversations are often brief. The potential for engrossed attention may last only a few moments and may not be repeated in future encounters. Consequently, we may ask how can we have a “relation” with people who will forever be strangers. To be sure, strangers may stay strangers. Yet, they can have this lived experience together, facilitated by the performances. In listening attentively and responding, the encounter is a form of care. Although it is not a mature relationship like those that develop over time, it is a caring relation nonetheless (Noddings 2000).

There is an important part for visitors to play at the festival. Strangers offer opportunities to respect those different from ourselves. Moreover, they help us to define ourselves in the process. And in a nation that is characterized by diversity, they call upon us to defend our differences. When scholars like Nel Noddings and Paolo Friere discuss the importance of such conversation in educational contexts, they are quick to point out that dialogue involves respect. It is not one person acting on another, but people working with one another. Rather than a monologic argument, dialogue is open-ended. “Neither party knows at the outset what the outcome will be” (Noddings 2000, 253). In the search for understanding, empathy, or appreciation, conversations can be serious or playful, imaginative or goal oriented. In the process of connecting us to others, there is always the risk of being misunderstood, misinterpreted, or even interrupted. Yet, the potential also exists for conversation to be a means by which acknowledgment and mutual appreciation may flourish.

Interestingly, due to the fact that they are simultaneously pervasive and typically taken to be inconsequential, such conversations often go unnoticed. They are the “small change” of everyday life (Hawes 2006, 25). Indeed, through their imperceptibility their ideological power is brought into play. While conversations can work as a medium of hegemonic control, they also may function as a powerful means of agency and subversion (Schechner 1985, 117). That is, while conversations often appear to be effortless or improvisational, rituals and customs—such as traditional greetings, terms of address, politenesses, and so forth—are a means of negotiating potential situations of risk for strangers, acquaintances, and friends (Bourdieu 1991; Turner 1987). These conversations, as acts of acknowledgment, bring people together in moments that create caring contexts of testimony and witnessing that take notice and honor others.

Moreover, Sheela’s performance offered an opportunity for performers and audience members to exist in relation to one another, making them coeval. That is, her critical play made time for both her and audience members to consider what it means to dwell in a deeply multicultural context like India or America. As Sheela’s performance continued, her stories provoked inquiries from the audience. In return, she asked questions. The play between these various actors created, in this moment, a sense of presence that was obvious. Visitors to the festival were able to come together, in a sense, and cultivate a feeling of acknowledgment that held the potential for an ethical set of relations, not only as Americans, but also as human beings. These exchanges reflected the type of acknowledgment that Alice Sickels had imagined.

As I indicated earlier, it seems to me that the acknowledgment that occurred through the conversations within the SILC booth were not chance. This is not to suggest that every interaction at the Festival of Nations culture booths would have such an outcome. Such moments are only a possibility. It is easy to imagine the ways that everyday realities inherent to any public performance (overwhelming crowds, fatigue, boredom, or power dynamics to name but a few) might preclude such possibilities. Yet, Alice’s unique design, growing out of a critique of the “Americanization” movement, hoped otherwise. Responding to the influx of immigrants in the first two decades of the last century—more than 15 million people—Americanization’s primary goal was to speed up the assimilation process. State-sponsored organizations and local community groups promoting Americanization pushed immigrants to speak only English or wear American attire. During this time many immigrant children were taught to be ashamed of their parents’ background. Parents hid their cultural history from their children, leaving a generation with questions about their family’s heritage. Documents in the Minnesota International Institute archives suggest that the Minnesota Festival of Nations’ beginnings were closely related to the “immigration work” started in 1919 by the local board of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA). Without the benefit of significant financial resources, this group offered citizenship classes, casework, services, and activities for immigrant women in an abandoned saloon called Jake’s Place in the city of St. Paul. By the 1930s, the International Institute broke off from the YWCA and began to define itself as a nonpolitical, interfaith, interracial social agency. In addition to group work services, it also began offering community members opportunities like foreign film features, foreign food lunches, the Street Party, the Pan-American Fiesta, folk dance classes, and, the most important, the Festival of Nations. As she wrote in her book, titled Around the World in St. Paul, “Although there had been programs of folk songs, dances and exhibits on a small scale all through the years since the International Institute was founded in 1919, the 1932 Folk Festival was the first attempt at a complete three-day festival” (75).

Of course, in some senses, the Festival of Nations has always been comparable to many other large-scale festival events supported by city, state, or federal organizations during the beginning of the last century. These festivals have often been credited with creating a way in which ethnic cultures can be preserved, revitalized, and valued in community life. Within these festival contexts, individuals often bond more strongly with their ethnic culture, allowing for them to satisfy a basic need for group belonging (Stoeltje 1992, 262). Consequently, ethnic groups are often pushed to feature the most “traditional” pieces of their heritage through means that reveal both cultural and rhetorical competence. In this process, the folk arts—be it dance, art, food, or song—provide a “sought-for common ground” where people can join together around “the interest that everyone felt in his own background” (Sickels 1945).

Certainly, this may have positive effects. For example, disenfranchised individuals may come to feel as though they are viewed and accepted as publicly committed members of the participating group. Experiences such as this one may have long-term effects for the individual, strengthening loyalty to their ethnic group and raising self-esteem. Moreover, ethnic festivals have been successfully used to bring back to life struggling ethnic communities by highlighting ethnic distinctions in the face of acculturation.

However, there are also serious concerns to take into account. Scholars responding to critical theory have, in recent years, considered the ways that festivals promote particular nationalist ideologies and histories, as well as facilitate the objectification of minority participants, despite the good intentions of organizers.11 Kirshenblatt-Gimblett (1990, 432) argues that “the danger here is what Stuart Hall calls self-enclosed approaches, which ‘valuing tradition’ for its own sake and treating it in an ahistorical manner, analyze cultural forms as if they contained within themselves from their moment of origin some fixed and unchanging meaning or value. The pressure is there to do just this.” Scholars, such as Elizabeth A. Povinelli (2002), also charge that in festival situations ethnic groups may feel forced to identify with liberal multiculturalism in order to gain access to public sympathy and recognition, thus pressuring subaltern and minority subjects to identify with the impossible object of an authentic self-identity—one that is traditional, domesticated, and nonconflicting. As argued by Povinelli (2002), this call inspires impossible desires to be an impossible object forcing diasporic subjects to attempt to perform an authentic “Other”—an essentialized presentation of self—in exchange for the “good feelings” of the nation.

In this scenario, it becomes the responsibility of minority subjects to make themselves recognizable. In many festival contexts, cultural exhibits exacerbate this problem by featuring stage appearances that convert everyday practices into “artifacts” that are alien to the ways in which they are encountered and produced when embedded in the flow of life (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1991). Separated from the complexity of the everyday, these cultural performances are often reduced to simplistic claims of authenticity and treated in an ahistorical manner. Therefore, while festivals do make visible traditions that would otherwise not have a public venue, it is also the case that those who perform those traditions tend to be represented in fixed terms. That is, despite organizers’ intentions of “making good” through the festival context, it is also clear that there are ways in which acknowledgment could potentially be compromised by the tourist discourses and practices that frame this event.

Alice hoped to overcome these constraints by designing a festival that “put a value on difference and encouraged people to be themselves” (Sickels 1945, 186). However, what, more specifically, distinguishes the Festival of Nations from other similar festivals is the great commitment and attention devoted to the relational process of inventing each year’s festival event. Alice contended, “All of them, old and new Americans alike, need first of all an opportunity to know one another, and in order to get acquainted, people must do something together. The Festival gives them a chance to work and play together” (Sickels 1945, 182–83). What was needed was a festival—founded on an ethic of care—that built in opportunities for acknowledgment. For Alice, such acknowledgment was a type of advocacy that potentially contributed to ideals of democracy and integrated attentiveness, responsiveness, and responsibility into a concept of citizenship. In this way, she envisioned the Festival of Nations as a “people’s festival.” As she stated: “The initiating and sustaining force behind the Festival is a clear conviction that firsthand experience in the democratic method and the feeling of actually being accepted as copartners in a democratic undertaking are more useful methods of helping people to become effective citizens of a democracy than formal instructions, preachments … Every person needs the experience of belonging—of the we feeling” (Sickels 1945). Sheela’s performance within the context of the India culture booth typified this “we feeling” by both inviting audience members into her artistic production and seeking acknowledgment for her complex position of being Indian in America. In this way, her performance, and the festival that hosted it, supported liberal multiculturalism and democratic discourse, but did so by presenting grassroots advocacy work as art. This innovative approach to a festival event piqued the curiosity of many leading social activists and politicians of the time. As the success of the festival grew, Alice was asked to advise government committees on immigration issues and act as a mentor for other folklorists and festival organizers. In particular, Alice’s focus upon the potential of acknowledgment within the festival context did not go unnoticed, and, as a result, many public figures visited the festival. One important example is Louis Adamic, who wrote Native’s Return, Thirty Million New Americans, From Many Lands, What’s Your Name? and hundreds of articles and speeches on the topic of immigration and assimilation.

Over the years, the Minnesota Festival of Nations has continued to grow, with Alice’s philosophy of acknowledgment continuing to inform the event. As one of the largest and oldest international festivals in the country, it has often been used as a model by other cites. Selected by the American Bus Association as one of the “Top 100 Events in North America,” and chosen by Discover America as one of the top two hundred events in America, it generally attracts over eighty thousand people to St. Paul’s River Center annually, including many organized tour groups from surrounding states. On specially designed student days, more than thirty thousand youth from a five-state area come to visit the Festival of Nations with their teachers. As the festival Web site notes, “Since 1932, the Festival of Nations has been committed to providing a hands-on learning opportunity for students to share the ties with our past and take pride in the riches of diverse cultures in our community.”

This festival performance context also provides such audiences time and space for reflecting upon important political questions: Who is welcomed in this national imagination that the Festival of Nations represents? What is the relation between the citizen and foreigner in the eyes of the nation, and how is that relation performed? As these questions and counternarratives emerge, the illusions of cultural and political transparency fade and complexities related to immigration and identity become more apparent. In cultural booths and their attending performances, these questions grow from conversations—some of which begin as idle chatter and evolve into friendly exchange. As Hans Georg Gadamer has shown, the success of such friendly dialogue is directly related to the enthusiasm participants show toward lingering and “giving in” to the conversation to gain mutual understanding and form relations. This “giving” between the self and the other grow from a shared desire to hear and acknowledge each other. In the festival context, such acknowledgment manifests as attention—attention that has at its center the notion of care. This acknowledgment may point toward a beginning. It seems there is promise in the ways that acknowledgment and its attending relations, like care and hospitality, may extend beyond institutional discourse and law. As Alice Sickels, Nel Noddings, and Selma Sevenhuijsen have all noted, these are political as well as moral concepts that help us to conceptualize humans as interdependent beings. They offer an enhanced sense of citizenship that foregrounds the values of attentiveness, responsibility, responsiveness, and an attitude of solicitousness toward others. In this process, acknowledgment is a gift performed in the name of potential relationality.