Care in Diasporic Performances

Shyamala Moorty sits on a cold, white toilet in the center of a bare stage. Her eyes move slowly across an audience that includes mainstream and South Asian American community members, war veterans, as well as university students and faculty. This diverse group has come together on a cold October night in Madison, Wisconsin, to participate in a 2005 performance called Rise. Hands shaking as she holds a newspaper, Shyamala listens to a cacophony of local and national media reports. Playing one over the other, each details the terrorist destruction of the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. Picking up a carefully folded American flag from the stage floor, she slowly opens it up for the audience to view and places her hand over her heart. Next, she begins to tell a story. It is an incident that occurred immediately after 9/11, while walking in her California neighborhood. She recalls:

I walked through my neighborhood passing lawns bordered by the flags of blue with white stars and stripes of red. I came upon a plain white house and I saw a middle-aged white man with glasses watering his lawn. I prepared my friendly stranger smile, only to be met with a grotesque scowl making a gargoyle statue out of his still body. Suddenly, his arm jerked, spraying the water at me. I was far enough away that the droplets didn’t physically touch me but I felt them pour down inside, flooding my lungs with shock. I struggled to breathe but he did it again. I turned to go in confusion. Only to see the same stars, brighter now against the red of anger. Watching me. Lining the street like a regiment. Watching me. Monitoring me. Ushering me into the future of Homeland Security.

Of course, Shyamala’s experience was not uncommon. Immediately following 9/11, South Asians experienced a record increase in incidences of bias, hate crimes, profiling, and discrimination. Indeed, in the first week following 9/11, hundreds of incidences of bias or violence against South Asians were reported in the United States (http://www.saalt.org).

However, what does make Shyamala’s testimony in this public forum unique is its artistic and inventive form. While wondering aloud about the politics of “home” and identity politics within contexts that are characterized by violence, Shyamala enacts the outlines of her bicultural ethnicity, as her body gracefully combines ballet, a traditional Indian dance called Bharatanatyam, and contemporary dance movements. Moments later she plunges the newspaper and the American flag down the toilet.

In her performance of Rise, this South Asian American activist and feminist performance artist extends an invitation—a call for acknowledgment. Asking for more than mere tolerance or simple recognition, she weaves together personal testimony and traditional cultural forms in inventive ways, with the hope of generating concern, care, and compassion among her audience. In doing so, Shyamala adds a meaningful perspective to the public sphere in an alternative fashion. Politics, of course, has always had an element of performance, though attention toward its importance has arguably increased in recent years (Alexander 2010). However, what interests me about Shyamala’s presentation is precisely the means by which her political performance persuades in unconventional ways. She relies less upon claims for recognition and more upon calls for acknowledgment that intertwine justice and care. She also embeds her testimony in traditional cultural forms to invite reflection and connection among those who gathered to witness it. That process encourages her audience to not merely think differently about citizenship, violence, and belonging, but also to feel differently about the plight of the South Asians she dramatized.

She uses this approach to explore a question that defines post-9/11 America: “What happens to a nation of individuals engrossed by constant ever-present threats to the home?” In doing so, she evokes inquiry into the experience of hate crimes and human rights offenses. How can people—citizens and immigrants, women and men, people of differing cultures and faithsdwell together in ways that address the complicated politics of our time, while simultaneously acknowledging that those marginalized and isolated by these complexities have disproportionately been victims of violence in their neighborhoods and their homes? These issues have been examined in political speeches and social protests; rational arguments have been made, and anger and outrage expressed. Yet when Shyamala invited consideration of them through the careful presentation of an eclectic mix of folk forms, classical dance, and dramatic narrative, she injected a new set of considerations into the public sphere. These considerations call for an emotional connection grounded in a “politics of care.”

As the concerns of our local communities intertwine with those of our national or global existence, it seems crucial to ask how people can “be-with-others” in ways that reflect a concurrent political commitment to justice and care. Shyamala’s questions point toward her specific experiences as a South Asian American woman, while also drawing attention to the problems of others who are situated in various ways across border lines. Her performance opens her audience to witness the challenges of diasporic life for those who are made to feel less than welcome while participating in the public sphere. This use of culture, or cultural politics as some have called it (Darnovsky, Epstein, and Flacks 1995), makes this sort of engagement more inviting for both the performer and the audience, enabling participation in policy debates, attempts at persuasion, and involvement in social protest.

Desi Divas is about performances, like Shyamala’s, that are a form of grassroots activism. This book offers a multisited ethnographic account of contemporary South Asian American women who participate in progressive politics and local community engagement. These women, in connection with feminist groups, human rights organizations, ethnic culture schools, and transnational art collectives, engage in the heart of contemporary controversies. Working through a variety of artistic media, they enter a dialogue and explore pressing questions related to immigration rights, ethnic stereotyping in the media, hate crimes, religious violence, educational policy, sex positivity, and gender identity. In doing so, they insert an often-marginalized diasporic perspective on current events—one that accounts for the ways in which the local and global intermesh in today’s transnational world.

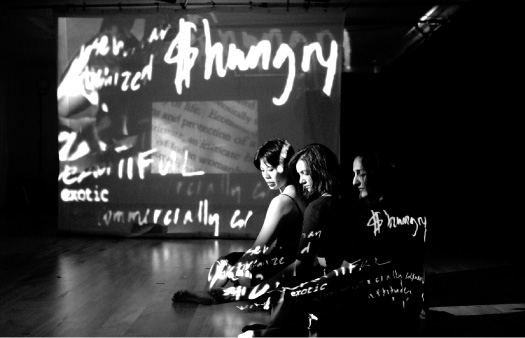

Post Natyam Collective members Shyamala Moorty, Cynthia Lee Ling, and Anjali Tata-Hudson. Photo credited to Andrei Andreev.

These South Asian American women are committed to arguing on behalf of social justice issues and the care for victims of violence—both social and domestic—and this is apparent in venues ranging from community theater spaces, folk festivals, poetry readings, to public blogs. Their performances often offer a social critique that risks public censure in the hope of spurring acknowledgment—for a chance to create a connection with others through a sharing of struggles and suffering. The use of political performance to engage with concerns and controversies is not exclusive to South Asian women in the diaspora, as illustrated by Kulich’s (1998) research on Brazilian travesti and Rupp and Taylor’s (2003) consideration of drag queens; nonetheless, immigrants from India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh also use performance as a political tool.

Accordingly, in this book, I strive to understand the ways women from diverse South Asian communities in the United States offer personal testimonies and narratives in culturally inventive ways that grow from their experiences in the diaspora. Since 1990, the South Asian community has been one of the fastest growing immigrant groups in the United States, with a population of over two million. The South Asian community in America includes individuals whose familial heritage originates in countries such as India, Pakistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal, as well as other diasporic communities in the Middle East, Tibet, Afghanistan, Trinidad, Kenya, and beyond. Although the War on Terror has certainly increased suspicion and prejudice toward South Asian immigrants, violence against and within South Asian American communities has a long history, extending back to the turn of the twentieth century—a history that connects to complex debates surrounding labor, race, nationalism, and religion. South Asian Americans were the focus of intolerance in 1907, when mobs forced nearly seven hundred people of South Asian decent to flee across the Canadian border, and in 1923 when the Asiatic Exclusion League successfully pressured the Supreme Court to revoke the citizenship rights of South Asians. Today, a large majority of U.S. citizens indicate that they favor policies that restrict or curtail immigration from certain non-Western countries. Moreover, within the mainstream there is, of course, the hate speech, hate crimes, and social intolerance that had taken root in the “dot busting” climate of 1980s and has once again found fruit in the “fifth column” suspicions following 9/11.

Within this group, women face particular sets of challenges. Significant disparities are evident along several variables such as immigrant status, population size, English proficiency, presence in the workforce, and education level. Moreover, feminist scholars such as Shamita Dasgupta (2007) and Grace Poore (2007) concur that issues like domestic abuse, sexual assault, and incest become particularly problematic in diasporic contexts for a variety of reasons.

Here, I foreground how, through cultural performances, South Asian women raise awareness in their communities about these problems, advocate for civil and human rights, and enter into political partnerships with other marginalized people. These performances invite audiences to understand local and national rhetoric, as well as the challenges of negotiating self and Other in an increasingly transcultural world. Their performances, I argue, inquire into pressing contemporary social questions by creating opportunities for ethical listening and the possibility of social action on the part of diverse audiences. In the process, many of these performances appropriate, transform, and juxtapose texts from popular, folk, and high culture, gathering together fragments to articulate a gendered diasporic perspective.

To understand the South Asian women’s performances at hand, I weave together two disciplinary lines of thinking—one in feminist theory and the other in communication theory—that point to the political legitimacy of using performance to seek a sense of connection and mutual understanding with others (Butler 2004; Dolan 2005; Hamera 2002; Madison and Hamera 2006; Hyde 2006; Noddings 2000; Oliver 2001; Robinson 1999; Sevenhuijsen 1998; Tronto 1993). At the most basic level, this perspective critiques the Habermasian view that the only legitimate speech in the public sphere is based on unemotional, neutral argumentation, as opposed to communication that employs sentiment and persuasion to achieve a goal. As Pajnik (2006, 394) argues, “the separation of the rational from the irrational in Habermas pushes aside emotion, imagination, and playful forms of action, which are regarded as not worthy of attention.” Political performance and the opportunity for acknowledgment that it creates counters this Habermasian view with the feminist critique of communicative rationality and other tenets of his public sphere theories (Fraiser 1990).

This perspective is grounded on the belief of the interdependence and relationality of all individuals, and thus, the moral obligation to advocate on behalf of those who are vulnerable. It also raises a series of deeper questions and intriguing possibilities for those interested in the intersection of politics and performance: What happens when an ethic of care puts compassion, empathy and presence into dialogue with the civic values of rights, duties, and justice (Sevenhuijsen 1998)? Moving beyond colloquial and romanticized notions of “care,” how can we understand care as a critical social practice? How might an ethic of care that manifests in performance contexts serve as “an act of acknowledgment”—a communicative effort that encourages a sense of connection and compassion? How might the act of acknowledgment provide an ethical response to suffering or injustice and lead us to perceive and judge political problems in innovative ways? In asking these questions, I am not simply calling attention to the ways everyday citizens engage in public debates in culturally inventive or artistic ways. Instead, I invite readers to look closely at the conditions under which care is provided when performers and audiences interact with each other.

The book, then, is concerned with engaging with debates over what constitutes legitimate discourse in the public sphere, and providing a feminist communicative perspective that centers on the ethics of care and acts of acknowledgment. As noted above, my examples that exemplify this approach focus on South Asian American women’s performances. I approach them as a form of grassroots advocacy that grows from public acts of acknowledgment. These small South Asian American community organizations and their critical use of cultural forms are a counterpoint to large nationally recognized groups and their conventional use of platform oratory. By paying attention to the ways in which political performance groups engage in the public sphere, I turn attention from political centers to peripheries, looking at critical communication from the margins of the margins.

This book also attends to the movements between ethnic and diasporic communities, publics and counterpublics, vernacular and high culture, as well as national and transnational ways of being. In short, this focus on political discourse, grassroots activism and cultural acts seeks to engage with discussions about the public sphere, question essentialized representations of South Asian Americans (especially women), redirect attention to intercommunity diversity, and offer a critical analysis of the conditions for ethical speaking and listening that exist in performance.

To understand the significance of these performances, this book takes a decidedly interdisciplinary approach. The topic—grassroots progressive performances by South Asian American women—has required me to draw upon and extend a well-developed body of scholarship that makes many important connections between performance and politics. The multisited fieldwork method I have used to gather material for this project grows primarily from the disciplines of anthropology and folklore.

To complement this approach, my readings of these performances combine theory from the areas of women’s studies, folklore studies, performance studies, political science, and communication. This decision to take a multidisciplinary approach signals a broader commitment to critically theorizing connections between art, inquiry, and activism across academic boundaries (Bauman 1977a; Conquergood 1992; Dolan 2005; Mills 1993; Pezzullo 2007; Pollock 1999; Rupp and Taylor 2003).

Scholars from these disciplines share a common interest in testimony, oral history, community building, citizenship, and social transformation. Whether through popular, folk, or high cultural forms, or an eclectic mix of the three, there is a growing appreciation of the ways that people can construct and participate in public life through voicing a critical perspective in cultural performances. Since the eighties, many scholars in communications and performance studies have found points of commonality through work in cultural studies (Brummett 1991; Gronbeck 1979; Madison and Hamera 2006; Rosteck 1999). Recent work has attempted to explicitly theorize connections between communications, the study of folk or vernacular culture, and performance studies (Abrahams 2005; Del Negro 2004; Dolan 2005; Garlough 2007; Hauser 1999; Howard 2005; Oring 2008; Pezzullo 2007). When studying women’s political performances, these connections are precisely what concern me the most.

Within this book, I understand performance in two intersecting ways. First, it is conceived of as theatrical practice, even though the political performances I focus on do not necessarily occur within a formal theatrical space. In particular, I am interested in exploring performances as a communal experience. It is both an embodied practice and a process of critical inquiry through which individuals engage in imaginative acts of social change. Moreover, I understand performance to be an intrinsic element of the customs, rituals, and practices of everyday culture—a part of the vernacular.

In this sense, performance is both a way of being and of becoming in social contexts (Madison and Hamera 2006; Markell 2003; Pollock 2005). It is relational, and arises in the stories we tell one another around the dinner table, on a community stage, or on internationally available Web sites. It is also potentially transformational and can move performers and audiences closer to a sense of “emancipatory potential” (Zipes 1983). The transformational power of performances includes, yet goes beyond, theater productions. Puberty rituals, ethnic festivals, folk dramas, inauguration ceremonies, holiday parades, storytelling—as well as everyday symbolic acts—all fall under the category of performance (Bauman and Briggs 1990; Madison and Hamera 2006; Richman 1991; Turner and Schechner 1987). Focusing on the political and democratic potential of these performances, I illustrate the ways they may hold the possibility for facilitating deliberation and debate, constituting identities, and broadening critical consciousness. I suggest that performances are a powerful means of community and political participation that encourage a range of conventional and progressive forms of engagement in the public sphere. Consequently, building upon the work of Abrahams (1968), Conquergood (2002), and Dolan (2005), among others (Garlough 2008; Oring 2005; Richman 1991), I trace new connections between performance and politics.1

Shah family sangeet at wedding. Author photo.

In this book, I explore performances that invite audience members to participate with one another and the topic at hand—to sing, dance, listen, discuss, and imagine together. As forms of historical intervention, they sometimes ask us to critically engage with the ways the past has been represented. They also address the politics of including marginalized narratives. These performances, each particularly situated within contexts of power, are characterized by an atmosphere of debate and offer a diverse range of strategies for civic engagement in local and global politics. They often offer oppositional or resistive perspectives or make the misuse of institutional power visible. They are rhetorical, seeking to influence or persuade audiences about an exigence as much as to entertain. These performances provide audiences ways of being together and create what Jill Dolan (2005) has called “audiences as participatory publics” (10).

South Asian American women from diverse backgrounds and cultural contexts have responded to experiences of violence, exclusion, and prejudice through such critical performances in the public sphere. These performances share a fundamental feature: they are political in nature. By this I mean that these performances artistically address and guide judgments about matters of civic importance, often encouraging engagement on these topics and participation in the public sphere. In some ways all politics is performative, yet not all political performances center on the use of art for political ends. When art is deployed in this way, the potential appears for broaching issues that would otherwise go unacknowledged in ways that engage cultural traditions in innovative and imaginative ways.

The performers and performances considered in the pages that follow speak to the possibility of dissent within climates of fear, where social differences challenge the limits of what can be said and the ways South Asian American women can appear as speaking subjects. In this and the following chapters, I explore how experiences of social intolerance and suffering can be expressed through performance in ways that represent the very differences that put diasporic individuals at risk. In doing so, I inquire into the cultural barriers and political challenges of protesting violence and loss—especially when there is pressure to stay silent or to voice one’s opinion in a solitary political idiom, shared community perspective, or singular epistemological account (Butler 2004).

These pressures are particularly acute in times of crisis. In such moments, minority voices are often deterred from publicly denouncing injurious, hateful, and harmful practices and policies. This problem directly speaks to debates concerning what constitutes nation and citizen, home and foreign, self and Other, and sparks related questions. Who should feel “at home” speaking about violence? Who has the right to speak and in what mode? What is one’s ethical responsibility, despite the costs, to participate in critical discussion and debate about violence in civil society?

And there are often costs to the expression of dissenting views in climates of fear. As Michel Foucault (2001) argued in Fearless Speech, artistic opposition requires the courage of a parrhesiastes—the ancient Greek name for one who speaks her mind and heart, despite social censure and the potential of physical retribution. In the tradition of Antigone, such citizens put themselves at risk in order to publicly protest in the face of hegemonic national and community unity. To a great extent, their strength resides in the ways in which they make themselves vulnerable to others, as they open a space for the questioning of law, cultural norms, and established reified social practices.

The use of artistic means to engage in acts of parrhesia embraces the obligation to speak the truth, even at great personal risk, on behalf of the greater good. Unlike such expression in political speeches and protests, the deliberate presentation of these arguments through cultural forms, movements, and narrative invites attention to a new set of considerations, ones that encourage an emotional connection to the issues.

Understanding performance in this way counters the view that the public sphere should be characterized by dispassionate, balanced exchanges (Pajnik 2006). Performance, by employing sentiment and relationality to evoke emotion and a sense of emancipation, provides a feminist critique of conventional notions of the public sphere (Fraiser 1990). As Pollock (2005) astutely notes,

Performance—whether we are talking about the everyday act of telling a story or the staged reiterations of stories—is an especially charged, contingent, reflexive space of encountering the complex web of our respective histories. It may consequently engage participants in new and renewed understandings of the past. It may introduce alternative voices into public debate. It may help to identify systemic problems and to engage a sense of need, hope, and vision. As live representation, performance may in effect bring imagined worlds into being and becoming, moving performers and audiences alike into palpable recognition of possibilities for change. (1)

For many years, minority leaders and activists have reminded their communities that such oppositional political performance may take a variety of forms. Today, the use of traditional cultural forms as potential vehicles for persuasive messages is apparent in the work of Chicano/as, Native American, African American, and Asian American groups. Indeed, anthropologists, folklorists, and communications scholars have spent decades documenting the innumerable ways in which community members use culture to persuade one another. This phenomenon, which I term “cultural action,” is a powerful means of social change.

For example, folklorists have developed a lasting interest in the power of strategic interpretation and appropriation to sustain, revitalize, and critically transform cultural traditions and communities. The work of Richard Bauman (1977, 1990, 1992, 1993), Giovanna P. Del Negro (2004), Deborah Kapchan (1996), Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett (1983), Wolfgang Mieder (1987), John Radner and Susan S. Lanser (1993), and Jack Zipes (1983) all speak to the ways that individuals purposively (re)make socially accepted folk forms to communicate marginalized or potentially threatening social perspectives. Indeed, it has been many decades since folklore has been conceptualized as a set of timeless, static traditions or remnants of a long vanished past. This we know: on an everyday basis, people in all corners of the globe work to create communities, think through their problems, make sense of their lives, and find new meaning through folk practices and performances.2

This work clearly demonstrates the need for scholars, government agents, business people, and others to enhance their understanding of other cultures and their methods of effective expression and communication. It also highlights the importance of understanding cultural forms found within particular ethnic groups. While some communications scholars focused on oratorical performances (Balgooyen 1968; Camp 1978; Ek 1966; Jones 1965; Prosser 1978; Smith 1971; and Starosta 1979) others are more firmly grounded in cultural ritual (Abbott 1987, 1989, 1996; Bahr 1988; Blythin 1990; Flores 1996; Hammerback and Jensen 1994), whereas others provide extensive research upon the historical significance of performative acts (Kaiser 1987; Lyons 1997; Morris and Wander 1990; Suleri 1992).

Research related specifically to women’s political performance also is robust. Feminist researchers, including Sue- Ellen Case (1990), Elin Diamond (1997), Jill Dolan (2005), Lynda Hart and Peggy Phelan (1993), and Vivian Patraka (1993) explore issues of gender, sexuality, feminism and patriarchy through the performances of everyday women. Some cases focused on the connection between performance and political demonstrations, considering the explicitly partisan aims of some performances. For example, as Case (2001, 146) notes, in the 1970s:

Even the protests themselves were theatrical. As Abbie Hoffman, one of the leaders of the Free Speech Movement, put it: “Free speech is the right to shout theatre in a crowded fire.” Campus protests joined other protests in the streets to represent rebellion against dominant codes of citizenship, national policy, and oppressive morality through activism and acting. Costumes visualized issues: the bathing suit composed of slabs of raw meat, which was worn in protest against the Miss California beauty contest, literalized the sense of the display of women’s bodies as meat. The burning of bras staged a revolt against restrictive fashion. A woman in an evening dress sitting in the midst of a garbage heap imaged the discounting of her body through the fashion of objectifying gowns. These political events were not functional so much as theatrical in their efficacy. “Demonstration” came to mean a performance of oppression and liberation through gesture and deed, forming both political action, through disruption, and a pedagogical device.

This can be seen in my research in Gujarat, India, where I have worked with grassroots feminist groups that conduct political outreach campaigns through street plays that use familiar cultural forms, such as songs, dance, and street theater, as a means to raise critical consciousness and mobilize groups of women.3

The performances that are the center of this book—whether in everyday life or on the stage—hold the potential to create a public forum for audiences to come together for a moment in time, feel allied with one another, and find a place to scrutinize public meanings important to the community (Farrell 1993). In some cases, performances also show audiences how they might become more active citizens by portraying potential means of participation to audiences who might not see themselves as agents in their own lives or political systems (Dolan 2005). As such, they are not simply ceremonial spectacles but demonstrate a “radical performance pedagogy” that create profoundly deliberative occasions and model the ways one might engage in a participatory democracy through attentive listening and dialogic reciprocity (Denzin 2006).

Sahiyar’s street play on sex-selection abortion. Author photo.

These performances are intensely reflective. They serve as mirrors for individuals and communities to view themselves, enacting narratives that create social solidarity, provide a place for critique that widens community borders, and make public what has been veiled (Conquergood 2006). Certainly, as Pollock (2005) notes, this approach does not always work.

As oriented as performance may be toward change, performance does not work instrumentally. In the symbolic field of representation, effects are unpredictable, even uncontrollable. They may be fleeting or burrow deeply, only to emerge in an unexpected place, at another time. They may unfurl slowly, even invisibly, on affective currents that may compete with what we think a given performance is or should be doing. Or they may refuse to come out altogether, preferring instead to rest in the discourses of “mere” entertainment or passing pleasure. (2)

Yet, the potential exists. In performing a desire for acknowledgment and by making claims of vulnerability, a petition for future relations and a stake in one’s own being is made. These diasporic performances by South Asian American women—what I will call diasporic performances—keep trauma visible and testify to the suffering of others. They participate in the rhetorical work of listening, speaking, deliberating, and knowing together. They “offer an opening for talk (or meaningful silence)—a creation of space and time that is personal, interpersonal, and significantly political” (Garlough 2008, 369).

I conceptualize “diasporic performance” as the practices and aesthetic acts of migrant, immigrant, and exiled peoples that address rhetorical situations from global, transnational, and postcolonial perspectives and negotiate exigencies in ways that are marked by hybridity and polysemy. To understand what I mean by diasporic performances, it seems fruitful to explore the boundaries of the concept “diaspora.” In recent years, diaspora has been a hotly debated concept in disciplines like anthropology, English, folklore, and cultural studies. Generally it refers to communities of individuals who have been displaced from their indigenous homeland due to colonial expansion, immigration, migration, or exile.4 In this way, diaspora suggests an awareness of belonging that is global or transnational in nature. However, as Janna Evans Braziel and Anita Mannur (2003) observe in their influential research in this area, while diaspora certainly may be characterized as transnationalist, it is not synonymous with transnationalism:

Diaspora refers specifically to the movement—forced or voluntary—of people from one or more nation-states to another. Transnationalism speaks to larger, more impersonal forces—specifically those of globalization and global capitalism. Where diaspora addresses migration and displacements of subjects, transnationalism also includes the movements of information through cybernetics, as well as the traffic in goods, products, and capital across geopolitical terrains through multinational corporations. While diaspora may be regarded as concomitant with transnationalism, or even in some cases consequent of transnational forces, it may not be reduced to such macroeconomic and technical flows. It remains, above all, a human phenomenon—lived and experienced. (8)

Diaspora describes experiences of living across borders, within diverse cultural traditions, and through disparate desires that complicate processes of translation and understanding. Yet it also attends to the ways immigrants cultivate and nourish social relations that connect places of settlement to places of origin. Taken together, it denotes a way of life, a hybrid culture, or perhaps, a third space between home and somewhere new that characterizes the diasporic experience.

Like all other aesthetic forms, diasporic performances offer an interpretive understanding of the world, mining its materials from the everyday lives of people. Appearing as public speeches, as well as stories, songs, dance, corporeal presentation, poetry, and material art, it deals with matters that are contingent, contestable, and multiply situated. Consequently, this book stresses rhetorical performances where South Asian Americans are actively engaged in their marginality by “protesting, reinterpreting, and embellishing their exclusion” (Tsing 1993, 5). Drawing from the work of anthropologists like R. K. Narayan (1993) and Anna Tsing (1993), my approach employs ways of thinking that are responsive to particularities, oddities, discontinuities, and contrasts; that is, to the “deep diversity” that characterizes these diasporic lives. As Clifford Geertz (2001) rightly noted, this creates “a plurality of ways of belonging and being, that yet can draw from them—from it—a sense of connectedness, a connectedness that is neither comprehensive nor uniform, primal nor changeless, but nonetheless real” (224).

Accordingly, I focus on the diversity of perspectives articulated by South Asian American women that relate to differences in religion, region, caste, and class, while recognizing women as individual commentators of their culture. In this way, my work draws heavily on and extends the body of feminist scholarship in folklore and anthropology that focused on the everyday resistance of South Asian women (Raheja and Gold 1994; Hansen 1992; Mills 1985; Narayan 1986; Richman 1991). Rather than focusing on women in positions of power—the exemplary women in history books or female political leaders—I look to everyday women and their vernacular ways of engaging politically. In doing so, I draw my cases from a variety of contemporary performance genres and locations. This allows me to explore the features and functions of diasporic performances that demand rhetorical acts of acknowledgment. In particular, it permits me to consider how calls for care and justice appear in these artistic renderings.

In Desi Divas, I am particularly interested in reflecting on how diasporic performances, like Post Natyam’s, make calls for acknowledgment that grow from an “ethic of care.” So just what is an “ethic of care?” For the past few decades, “ethics of care” has been an important focus of theory and method for feminists, moral philosophers, communication studies scholars, and political scientists (Engster 2007; Gilligan 1993; Held 2006; Tronto 1993). These scholars draw from a range of philosophers, including Aristotle, Heiddeger, Arendt, Levinas, Foucault, and Ricoeur, to make a varied set of claims about how we might understand the concept of care, its function, scope, practical manifestations, and political purposes in public spheres.

At its core, this body of scholarship argues that care is important to everyone (Clement 1996; Held 2006; Larrabee 1993; Robinson 1999; Sevenhuijsen 1998; Slote 2007; and Tronto 1993). It is a fundamental social good. In our daily lives, “care is both a value and a practice” (Held 2006, 9). That is, care is more than a moral ideal; rather, it is a moral orientation that guides individuals toward considering people’s needs and finding ways those needs may be addressed. As a value, care relates to issues of morality, focusing on aspects such as responsibility, vulnerability, and trust. As a practice, caring, in all its stages, entails relationality (Tronto 1993). As Held (2006) observes, “Even when one is just beginning to understand another’s needs and to decide how to respond to them, empathy and involvement are called for” (34).

Post Natyam members Cynthia Lee Ling, Shyamala Moorty, and Anjali Tata Hudson. Photo credited to Andrei Andreev.

For many scholars, their interest in an ethic of care reflects a concern with the traditional distinctions made between the concepts of “care” and “justice.” As Virginia Held (2006) remarks, an ethic of justice, such as Kant’s moral theory, often “focuses on questions of fairness, equality, individual rights, abstract principles, and the consistent application of them” (16). In contrast, an ethic of care often concentrates on “attentiveness, trust and responsiveness to need” (Held 2006, 15). Working from this set of oppositions, care seldom figures into a conceptualization of citizenship that is most understood in the terms of justice, rights, and judgment associated with distance and impartiality.5

Put another way, care is more than a moral concept. It is a political concept as well. The ethic of care calls into question the universalistic and abstract rules of dominant moral theories, in order to revalue emotion and relationality when confronted by the claims of others in the public sphere. Care helps us to understand humans as fundamentally interdependent beings. Caring relations extend to the social ties that bind groups together and include the foundation on which political and social institutions can be built. It touches upon even global concerns that citizens of the world can share.6

Robinson suggests that a critical ethics of care:

[This conception] starts from the premise that people live in and perceive the world within social relationships; moreover, this approach recognizes that these relationships are both a source of moral motivation and moral responsiveness and a basis for the construction and expression of power and knowledge. The moral values of an approach to international ethics based on care, then, are centered on the maintenance and promotion of good personal and social relations among concrete persons, both within and across existing communities. These values, I argue, are relevant not only to small-scale or existing personal attachments but to all levels of social relations and, thus, to international or global relations. (2)

A critical ethics of care, in the context of social and political relationships, aims to reveal the relationships that exist among and within groups. At the same time, it maintains a critical stance toward those relations. Understood this way, the ethics of care can be seen to relate not only to personal relationships among particular individuals. It also extends to a diverse set of institutional and structural relations in and across societies.

Selma Sevenhuijsen (1998), for example, also conceptualizes care as a critical practice that serves the goals of citizenship. Her work addresses what happens when we “entangle values derived from an ethic of care (attentiveness, responsiveness, responsibility) into concepts of citizenship” (iii). In this process, we reach toward a concept of citizenship that is enriched and better able to cope with diversity and plurality. Care is de-romanticized, enabling us to consider its political virtues. In particular, Sevenhuijsen argues that care is a form of social agency that can inspire careful judgment—and judging is a principle task of citizenship and collective action within a democracy.

Building from this theoretical base, the question Robinson (1999) and Sevenhuijsen (1998) approach but do not answer is what communicative strategies might such a critical ethic of care entail? I argue that one such communicative strategy is the act of acknowledgment. This leads me to explore three key questions within performance contexts characterized by an ethic of care. Through acknowledgment, how might one “judge with care” in performance contexts? How might performers facilitate the creation of participatory publics through an ethic of care in performance? Moreover, how does self-care manifest in performance? We take up these questions through an explication of the notion of “acts of acknowledgment,” the synthesis of these perspectives.

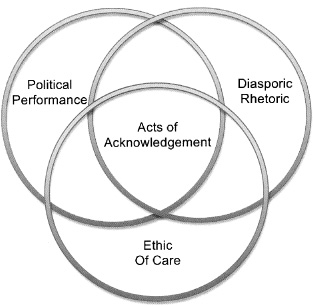

These three dominant strands of theorizing—the first, which expands and politicizes the notion of performance; the second, which connects this to rhetoric from the margins and the issues of hybridity; and the third, which considers the moral and political conceptions of an ethic of care—can be wound together to situate the rhetorical performances of South Asian American women considered in these pages. Indeed, I contend that it is at these concepts’ intersection that the notion of acknowledgment resides, a rhetorical manifestation of the ethic of care in a performative context.

To illustrate this, I offer the following visualization while at the same time recognizing that doing so simplifies a complex set of interrelationships. Nonetheless, it is important to understand how these three strands, and the three field spaces that they represent, come together. Contemporary research on the concept of “acknowledgment” often appears in literature at the intersections of rhetoric and philosophy, specifically ethics. It also is typically referenced in conjunction with a substantial and growing body of literature on recognition studies (Cavell 1987, 2005; Markell 2003).

For example, in the disciplinary area of rhetorical studies, Michael J. Hyde (2006) recently published an influential book, The Life-giving Gift of Acknowledgment. Hyde’s orientation on acknowledgment grows from an engagement with the work of Heidegger and Levinas, with an eye toward Aristotle and the Sophists (Garlough 2007). He offers a rhetorical orientation toward acknowledgment that reflects an abiding concern with human contingency, civic responsibility, rhetorical competence, and social wellbeing. Here, Hyde argues that acknowledgment is a way of “being-for-others.” It is deeply relational, a means of giving attention to others in our lives. It is a form of communicating care. For this reason, he explores a phenomenology of acknowledgment, not only to understand the existential nature, but also its connection to rhetorical performances in heightened moments of crisis and in the realm of the everyday.

Acknowledgment, Hyde (2006) argues, embraces both humanity’s vulnerability and our strength as individuals to address that fragility. In acknowledgment, there is the potential for healing and hope essential to communal spirit, social activism, and the moral well-being of humankind. Conversely, a lack of acknowledgment is a fundamental precondition for suffering. The result is often a social state of being marginalized, ignored, or forgotten. There are, of course, innumerable local, national, and global ramifications for such a lack—all of them forms of “social death,” according to Hyde. This state of being appears, for example, in institutionalized forms of negative acknowledgment like racism or sexism. In particular, Hyde’s Levinasian sense of acknowledgment and “the Other” lays the groundwork for how we might more ethically acknowledge those who are “foreign” or “a stranger” to us in increasingly globalized contexts.

In these moments, Hyde (2006) argues, acknowledgment, as a way of being-for-others, shows itself to be “more than recognition.” This statement gestures toward a larger scholarly debate, spanning across disciplines, that has attempted to differentiate the connections and distinctions between the terms “recognition” and “acknowledgment.” That is, although etymologically both sets of terms find their root in the concepts of anerkennung or anerkennen/erkennon, many believe that the conflation of the two in everyday language is deeply problematic. Indeed, Calvin O. Schrag (2002) argues that “the blurring of the grammar of acknowledgment with the grammar of recognition is one of the most glaring misdirections of modern epistemology” (117–18).

So what characterizes the distinction between the two? Patchen Markell (2003, 1), in Bound by Recognition, suggests that,

Life is given texture by countless acts of recognition. From everyday interactions to the far-reaching deliberations of legislatures and courts, people are constantly asking the interconnected questions: Who are you? Who am I? Who are we? In answering these questions, we locate ourselves and others in social space, simultaneously taking notice of and reproducing relations of identity and difference. And in this way, we orient ourselves practically: we decide what to do and how to treat others, at least partially on the basis of who we take ourselves, and them, to be.

This accords with Paul Ricoeur’s (2005) sense of recognition, in The Course of Recognition, where he outlines three major senses of the word: “(1) To grasp (an object) with the mind, through thought, in joining together images, perceptions, having to do with it; to distinguish or identify the judgment or action, know it by memory; (2) To accept, take to be true (or take as such); and (3) To bear witness through gratitude that one is indebted to someone for (something, an act)” (12). Recognition involves the difficult practice of seeing something within the terms of something else. We recognize a thing as a thing (Markell 2003). We attempt to recognize the strange, so that it becomes identifiable. And as Gadamer (2004) aptly notes, there is a joy in recognition—in making meaningful associations, even when regarding unpleasant subjects of the association (17). In sum, recognition provides our lives “depth and continuity” (Markell 2003, 2). Without markers of identity, we would be unable to find our way in such a complicated and chaotic world.

Some would assert that such recognition is a matter of discourse. That is, when recognition is at stake, justice is provided when people are well represented in print, in media, and in everyday speech. That is why, in educative settings, “through literature, art, pictures, historical accounts, food, dress, student genealogies, days of cultural recognition and many other practices, teachers embrace the folk paradigm of recognition either implicitly or explicitly” (Bingham 2006, 328). However, there also can be significant costs associated with struggles for recognition. As scholars like Arjun Appadurai (2003), Homi Bhabha (1980), and Charles Taylor (1994) have argued, recognition also serves to institute and then sustain relations that are characterized by inequity, prejudice, or discrimination. Building from this scholarship Markell (2003) contends, “If recognition makes the social world intelligible, it often does so by stratifying it, subordinating some people and elevating others to positions of privilege or dominance” (2–3). In this sense, recognition may be a “medium of injustice,” as seen in acts such as racial profiling.7 Kelly Oliver (2001) argues that the very emphasis upon “struggle” is the problem. She says within the “pathology of recognition” the struggle to become objectified, in order to be recognized by the sovereign subject, is part and parcel of the dehumanizing practices of the dominant culture. Perhaps we should, as a first step, refuse to “struggle.”8 Alternatively, it may be that we need to move beyond the language of recognition to the more promising and meaningful term of acknowledgment and the acts that call for it.

Theorized in this way, acknowledgment is not interchangeable with recognition. Rather, I would suggest that it refers to a related but distinct set of behaviors and practices. To begin, building from the work of Michael J. Inwood (1992), it is important to note that often recognition may be private—as when one realizes one’s error or a truth. When recognition is private, the concept of acknowledgment cannot be substituted because one may recognize an error but not acknowledge it publicly (245). Also, when we identify a thing or a person as a particular individual, recognition is not necessarily replaceable by acknowledgment. That is, one can recognize someone without acknowledging them (erkennon). In contrast, acknowledgment (anerkennon) goes further to include the following practices: “(1) To admit, concede, confess a thing or person to be something, (2) to endorse, ratify, sanction, approve or take notice of something or a person, and (3) to take notice of someone in a special way or to honor them” (Inwood 245). This exceeds my intellectual identification of a thing or a person. The bigger question is how I should behave toward others. All this goes beyond simply seeing the other as a person; instead, one must become aware of and confirm the other. As Hyde (2006) states, “the act of acknowledgment is a communicative behavior that grants attention to others and thereby makes room for them in our lives …. There is hope to be found with this transformation of space and time as people of conscience opt to go out of their way to make us feel wanted and needed, to praise our presence and actions, and thus to acknowledge the worthiness of our existence. Offering positive acknowledgment is a moral thing to do when approaching the Other” (1).

I believe a focus on acts of acknowledgment is significant to understanding the diasporic performances of South Asian American women featured in this book. I would argue that the concept of acknowledgment may be useful precisely because it highlights where the feminist debates on care and justice intersect. Put differently, through a feminist reading of the performances in this book, it becomes clear how especially in times of crisis an “ethic of care” and the “ethic of justice” are fundamentally interlaced within acts of acknowledgment. These performances inspire moments in which audiences begin to care for and feel themselves allied with one another, as well as with a wider, more diverse sense of a public.

This seems particularly important with respect to critical scholarship that seeks to understand subaltern and counterpublic spheres and modes of enacting resistance and citizen exchange. As Raka Shome (1996) noted more than a decade ago, we need more critical scholarship that addresses “how rhetoric functions in hybrid borderlands and cultural spaces, as well as how rhetoric aids in the creation of diasporic disjunctured identities” (601). There is very little work of this kind in rhetoric or performance studies that focuses specifically on South Asian Americans, let alone South Asian American women. In most cases, research on South Asian Americans’ political performances tend to grow out of the disciplines of anthropology, folklore, or political science (Mills 1985; Mohanty 1993; Shukla 2003). These scholars are more likely to draw on postcolonial theory or work in recognition studies to construct their analyses (Hegde 2005; Mookherjee 2005; Shome 1996).

My insights in this book are informed by these perspectives as well. However, I also hope to contribute to these discussions by focusing specifically on the rhetorical work that acknowledgment accomplishes for particular South Asian American women who engage with issues of social justice, violence, and suffering. In taking this approach to the study of acknowledgment in diasporic performance, I am able to look closely at the intersection between gender and wider political relations, particularly transcommunal and global/local connections. This allows exploration of the cultural heterogeneity within and relationships among South Asian American communities, in terms of religion, regionality, nationality, caste, and class differences.

My understanding of the diasporic performances explored in this book grows from a decade of interviews and ethnographic fieldwork with a diverse range of South Asian American community groups, from feminist collectives in San Francisco to secular ethnic schools in Minneapolis. In this sense, Desi Divas is a multisited feminist ethnography. I use traditional fieldwork methodology in a variety of locations both spatially and temporally to follow exigencies and conflicts related to women’s issues that transcend boundaries (Behar 1995; Marcus 1995; Minh-ha 1989; Visweswaran 1994).

Without question, it has been a humbling experience. In these contexts, these women often operate in a volunteer capacity with few economic resources. Consequently, they strategically use the cultural resources they have at hand in order to raise awareness, form alliances, and create constituencies. They make impressive personal sacrifices, in terms of time, economic gain, and personal risk, to create valuable opportunities for people in need, from women who have experienced domestic abuse to communities torn apart by religious intolerance.

My methodological approach for this research was triangulated. It included arranging focus groups after performances and conducting surveys with organizational members. To uncover “lost” documents about early South Asian and South Asian American performance, I engaged in archival research at the British Library, U.C. Berkeley’s South Asian Library, Wisconsin and Minnesota’s Historical Societies, the University of Iowa’s Redpath archive, and the International Institute of Minnesota. With an eye toward online presence, I studied the blogs and Web sites associated with the performers and activists and corresponded regularly with them over e-mail.9

In addition, so that I could understand their efforts, these women generously included me in their grassroots activities and performances, sharing their sense of the world around them. In the process, I have had the opportunity to speak, listen, and learn with women from diverse backgrounds—all positioned differently with regard to nationality, immigration status, sexual orientation, age, education, and economic privilege. We asked difficult questions of one another and shared personal stories. We sat in silence and thought together. We wrote together. There were conversations that twisted and turned. Some led to understanding, others not. All required trust. And, as such, trust became a topic of conversation to be continually revisited.

In my experience, trust often emerged from exchanges in which I acknowledged my own privilege and positionality. Consequently, I believe discussions of privilege or positionality should not come after six months of interviews or as a brief aside within a personal conversation. They should not happen as one is writing up the ethnography, to function as context for the reader. Moreover, they should not appear as an apology for difference, for we are all positioned in particular ways along axes of power. Rather, they should be a means of honestly addressing power within relationships, while simultaneously communicating care. They are a way to acknowledge the risk people take when sharing with another. These discussions can be messy, uncomfortable, and even unpleasant, as well as filled with moments of connection and self-reflection. Most important, they provide the potential for acknowledgment that exceeds intellectual recognition.

I had a good deal in common with the women I worked with—sharing a passion for grassroots volunteerism and activism, theater, and dance. However, with each unique person, there were power issues to consider that included privilege associated with race, class, academic positioning, and so on. Consequently, in my account of our interactions I take very seriously feminist critiques regarding antiessentialism and endeavor to pay close attention to historical and social context, as well as intersectionality. Yet, in my writing I certainly can’t escape my own positionality, as well as the tasks of evaluation and interpretation (Behar 1995). This text is written in my voice and structured to address my own research interests. We are colleagues, friends, and allies—and our dialogues together have taken a form that was co-created and bound by ethics that have been explicitly discussed over many years. But, of course, sometimes words fail. Sometimes people fail us or we fail others. However, I believe by disclosing something of ourselves and openly addressing the exploitation that is possible within the fieldwork and ethnographic process there is a will to hope.

Does such acknowledgment overcome all the concerns about ethnography that feminists have highlighted (Stacey 1988)? I’m sure it does not. But then again, I’m not sure that any relationship can overcome such potentialities. Fieldwork is inevitably risky business. People may reveal things they wish they had not. People may be disappointed when what they have revealed is not published. But oftentimes there is potential for good as well. We can learn to care about each other’s lives in long-term ways and maintain relationships across time and space. We can listen attentively when one person offers a delicate performance of the self—a sense of self that is multiple, shifting, messy, contradictory, and relational. We can keep promises about secrets, even at cost to ourselves. We can bear witness to loss. We can decide not to give up because there are issues of privilege to address or power dynamics to negotiate. I believe it is in these relationships where our humanity emerges—when we care even though we will never care perfectly.

In these ways, my role as a researcher has been characterized not just by observation or participation (although these are important parts of my approach), but also by conversation. At the center of this approach is an abiding dialogue with the people I have collaborated with over the years. In sharing time and space with others, this dialogic approach is, in many ways, an exercise in mutual acknowledgment. That is, I have strived in each encounter to do ethnography with the people at field sites and not of them (Conquergood 1992; Das 2007; Fabian 1983; Madison 2005).

I believe strongly in the ethical potential of these conversations among researchers and those with whom they collaborate. Such dialogue “involves participants in a heightened encounter with each other and with the past, even as each participant and the past seem to be called toward a future that suddenly seems open before them, a future to be made in talk, in the mutual embedding of one’s vision of the world in the other’s” (Pollock 2005, 3). Careful fieldwork conversations have provided opportunities for me to “bewith-others” in ways that allow for a puzzling through of what is known, not known, and may never be understood.

In this process, I pay particular attention to the silences, as well as the inconsistencies and gaps that gesture toward a nuanced sense of individuals and their everyday lives. The ethical potential of ethnography, to me, has a good deal to do with how we struggle together to make ourselves known to others. This is sometimes characterized by playful ways of thinking and speaking, a movement that nurtures understanding and creates, for a time, a sense of connection among participants. The idea here is not necessarily to gain information, but to experience together the movement of words in a genuine dialogue. What continues to interest me about these moments is the heightened awareness of giving itself—the rising up and flowing of thought, an experience of revealing and concealing. The value of this process, fraught as it can be with confusion and misunderstanding, is the intersubjective struggle—the communication that occurs among people engaged in a process of giving. Such moments elevate observers and participants above the present and add to a deep and abiding dialogue that creates meaning. To my mind what this means, above all, is that we must embrace our own and other’s vulnerability within this fieldwork process and attend to this with the appropriate care and ethical considerations.

As must be clear, this book is strongly influenced by feminist critiques of ethnography, although I certainly do not take feminism as a stable referent for my readings of these performances (Abu-Lughod 1986; Tsing 1993). Women everywhere are not the same. Nor do women always speak from the gender identity of “woman.” The task of this book is to attend to local critiques of prevalent gender norms and work to expose the gender dynamics in which “official stories” of culture are told, invoking and criticizing dominant representations of culture. To do so, I focus upon men and women as individual commentators of their culture(s). As a consequence, this book resembles critical ethnographies found in anthropology, while providing the deep textual analysis typical of many critical rhetorical studies. In each chapter, I weave together rhetorical theory, performance and folklore studies theory, and critical feminist theory with interviews and thick description of political cultural performances by South Asian women. Like many other rhetorical scholars and critical ethnographers, I share with the sophists “a commitment to particular practices, pluralism, unpredictability, local performances, playfulness, and partial truths” (Schiappa 2001). I attempt to foreground many voices to provide a complex sense of the South Asian American community, to ensure their performances live beyond the immediate moment, and to “preserve the pleasure of the affective gifts these moments share” (Dolan 2005, 9).

This approach to research is rooted in my own positionality as a researcher, as my interest in South Asian American communities and women’s performance is both scholarly and personal. That is, although I am not South Asian American, in a sense, I am implicated in the diasporic experiences I describe. My early experiences growing up in a small Protestant family, in a house next to a cornfield and across a gravel road from a rock quarry in rural Illinois, certainly limited my early sense of the global. For my early schooling, I walked to a six-room schoolhouse that lacked a library, gym, cafeteria, music or art room, as well as diversity.

However, when my family moved to Madison, Wisconsin, I began a relationship with Dhavan Shah, a first-generation South Asian American whose parents had immigrated from Gujarat, India, in the late 1960s to work as scientists at the University of Wisconsin. His suburban home—often filled to capacity with aunties, uncles, cousins, and close family friends—was a vibrant place that smelled of turmeric and peppers and was filled with engaging conversations spoken in Gujarati. This was my first long-term experience with another culture. When I reflect on it, this experience also provided my first informal “training” in ethnographic methods. In many ways, I was “hanging out” in the Geertzian sense (Geertz 1973): watching the ways cultural practices changed over time and in different contexts, depending on the positionality of the performer—be it auntie, sister, cousin, or friend; learning to listen closely and quietly in an engaged way to what I did not understand and to what some might not explain to me.

Family photo of wedding in Houston, Texas. Author photo.

The Garlough-Shah family. Author photos.

Eventually, Dhavan and I traveled to India together. There, I began working with two South Asian feminist organizations in Gujarat, studying the ways women appropriate folk practices and use them in street theater performances and political protest contexts (Garlough 2007).

My daughter with her cousins. Author photo.

Some years later, we began our own family, in which we have tried to maintain a dynamic interplay between cultural traditions. We live in a small town in Wisconsin, and from the outside, our life together likely appears somewhat provincial, filled as it is with soccer games, fishing, dance lessons, and family trips to the Wisconsin Dells. However, sometimes people simply are not what they initially appear to be in the local grocery store aisle or academic conference. And in the latter case, I am often surprised at how quickly the jump is made to conclusions about my positionality. Although it is not immediately visible, I also am embedded in tight networks that tie me to a home in Gujarat, India, nearly 7,800 miles away. We travel regularly to this place in India, participate in ethnic schools, take part in South Asian American community organizations, support local cultural events, and worry greatly about racism, hate speech, and other forms of violence after the Gulf War and 9/11.

My children have grown up with their grandfather living just a few miles away and our luck is such that he enjoys cooking homemade Gujarati meals for us each week. Large family events and holidays with relatives provide my children with opportunities to be at home with diverse ways of being “Indian American.” It is in these same familial and larger community networks, I first learned about women’s performances in India. At wedding celebrations—including my own—Dhavan’s aunts took the time to teach me women’s folk songs, folk dance, and rituals for luck in the future. Today, when I complain of a sore throat, friends in the community ply me with folk remedies using ghee, warm milk turmeric, and other herbs. I offer these examples, as a way of making clear that these performances have become an important part of my daily life.

In this way, though my positionality is “Other” (Abu-Lughod 1986), I have been close to the experiences and events that I explore in this book. I trace an exploration that has spanned more than twenty years and deepened my understanding of South Asians in America as much as it has contributed to a changing understanding of rhetoric, ethnography, gender studies, and folklore. In a sense, doing fieldwork for this book was not so much a trip to an exotic location but a trip homeward.

My interest in acknowledgment began during fieldwork with the San Francisco feminist collective called South Asian Sisters. In particular, it was after witnessing a spoken-word performance by Shyamala Moorty at an event called a Day of Dialogue that I began thinking through these issues. As I watched her performance, I was fascinated by her eclectic approach to addressing the social problems facing her community—locally, globally, and transculturally. Her performance was generous and emotionally open, as well as aesthetically and intersubjectively powerful. It connected diverse audience members and challenged them to acknowledge not only issues of violence, but also her experience of suffering.

Here, the power of bearing witness through such testimony was not simply located in the “proof” that Shyamala provided. Rather, it came from a sense of “singularity” that her words evoked, the sense of presence, of having experienced it yourself (Derrida 2005). Such a process of witnessing is often painful, requiring one to relive moments of suffering, creating a sense of isolation (Nancy 2002). Yet, at the same time, to know oneself through this pain is to be in relation to the Other—to all others who have suffered and are still suffering. In this sense, she is both an eyewitness to historical facts and a witness to a truth about humanity and suffering that transcends those facts (Oliver 2004). Her testimony is a poetic and deeply personal account of the issues of the day. It is the first of many accounts that will appear in this book concerning the feminist performances imagined and enacted within contemporary South Asian American communities as acts of acknowledgment.

I recount this performance to illustrate at the outset what is at stake in this book and what I hope to accomplish by its end. To begin, this personal account demonstrates the wide swath of discourse and performance I consider important to attend to for scholars interested in South Asian American activism by women. It also provides evidence of my conviction that performance studies, folklore studies, and women’s studies have something crucial to contribute to one another. My sense of the important connections among these disciplines will become clearer in the chapters to come, as I explore the political and playful dimensions of South Asian American performances in cultural festivals, performance art events, Web pages, and spoken-word pieces. In these performances, I trace how violence against South Asian Americans relates to naturalized notions of the American “nation.” I consider how the interplay between “foreign” and “home” bears on our willingness to embrace those unlike ourselves—the Other. I explore how essentialism and stereotyping—especially within the context of identity politics—work to marginalize individuals not only within mainstream society, but also within their own communities.

The aim of this book is not to offer a complete presentation of community identity. Rather, it showcases South Asian American women’s performances that are not readily categorized and, indeed, may be characterized by self-contradiction. The burden of this book is to maintain the complexity of these performances, as well as the exigencies, contexts, and South Asian American communities they represent. Doing so also involves bringing these performances together and critically examining each of them in relation to the Other. The subsequent chapters take the form of overlapping conversations that seek to understand the interrelationship of acts of acknowledgment, exceptional violence, and the subtle forms of hostility perpetrated by institutions.

Performance has always held a prominent place in political movements for social justice. From AFL-CIO ballads about the burning of textile mills to the use of satirical anecdotes in soapbox speeches by the NAACP, everyday people have used the cultural resources available to them in order to comment upon the political, social, and economic issues they face. Like other marginalized groups before them, South Asian Americans have performed their desire for social justice and compassion in the public sphere through many different modes, from folk songs and speeches at political protest rallies to ethnic pride parades. Protest performances often take on elements of the “theatrical” as diasporic community members addressing exigencies within their communities through both words and bodies. Indeed, there is a long tradition of political performances by South Asian American grassroots actors, although some of the early history is not well documented. This chapter seeks to fill this gap and provide context for the ideas that will guide my ethnographic cases of “acts of acknowledgment” that are a part of art and not always sought out or allowed in politics.

From platform speeches to theater pieces, South Asian Americans have addressed issues such as immigration, citizenship rights, and human rights violations in a variety of ways over the last two centuries. Some of these early examples provide instances of more explicitly political performances in the service of issue advocacy. Understanding this overlooked activism offers a crucial context for understanding the contemporary women’s performances discussed in later chapters. For example, few know the work of Indian activist and early feminist Pandita Ramabai Saraswati, who traveled in the United States in 1886 to raise awareness and money to build homes for child widows in India. By contrast, more people are familiar with the oratorical performances by her contemporary Swami Vivekananda at Chicago’s 1883 Parliament of World’s Religions. Yet few are aware of the controversies that ensued over his speeches, due to their perceived “erotic” effect on white, female audience members.

There are, of course, other important examples of political performances by women and men throughout the early decades of South Asian American immigration, particularly within the highly controversial Gadar movement (1912–1919). Individuals involved in this grassroots movement for Indian independence worked from American shores to support fledgling nationalist struggles against British colonialism. To support this effort, activists wrote protest songs based on Indian folk music and performed them at political events, a practice similar to many marginalized groups in American history, such as African Americans during the civil rights movement or union laborers with the AFL-CIO. Twenty years later, South Asian American political activists, like Sudhindra Bose, performed on the popular Chautauqua circuit across the Midwest to speak about Indian cultural heritage and immigration rights in response to anti-Indian sentiments stirred up by critics, like Katherine Mayo, who were supporters of the Asian Exclusion Acts.

These early performances offer an interesting contrast with the contemporary political performances that are the focus of this book. Yet they also contain elements that herald what was to follow. After the “brain drain” in the 1960s, a new influx of immigrants organized ethnic parades and cultural heritage events to rally against hate crimes like “dot busting” in their neighborhoods. Soon after, women’s activism emerged from within local South Asian American communities that grew out of broader national, transnational, and global contexts. Today, a second generation of South Asian immigrants is voicing its political opinions through popular culture forms like Bhangra and hip-hop, spoken-word poetry, or political blogs (Sharma 2010). Understanding this history provides the background for appreciating the three case studies this book highlights and the acts of acknowledgment of featured performers.

Public expressions of ethnic culture, such as parades, pageants, and festivals, are often enjoyed by mainstream citizens as a way of consuming symbolic aspects of multiculturalism. Certainly, they provide a means of virtual tourism and an opportunity to experience the carnivalesque. However, between the performance of folk songs or dancing, there are always exigencies to be addressed, social critiques to be explored, as well as constraints and limitations to be negotiated based on mainstream or in-group values and norms (Prasad 2000; Purkayastha 2005; Sharma 2010). Chapter 3 presents the first of three ethnographic case studies that grow out of my decade of fieldwork studying such artistic political performances. Here, I explore “ethnic cultural performances” by progressive South Asian American activists at the Minnesota Festival of Nations in 1999 and the resulting tensions between acknowledgment and recognition at this event. Folk festivals have long been understood as important sites for performances that constitute local and national community identities, as well as political agendas. This is undoubtedly true of the Festival of Nations, one of the largest annual folk festivals in the world.

This event was originally imagined by Alice Sickels, who served as the director of the International Institute of St. Paul, Minnesota, from 1931 to 1944 and was a nationally renowned grassroots community activist for immigrant rights. Unlike proponents of more conservative “Americanization” efforts who sought to expunge “ethnicity” and encourage total immersion into mainstream society, Alice emphatically argued for the value of cultural differences. Consequently, as part of her grassroots political efforts, she created a public festival to bring together strangers from different ethnic communities to celebrate what a tolerant and inclusive America might look like—simultaneously supportive of both American citizenship and ethnic cultural heritage. This folk festival, she believed, needed to be characterized by an “acknowledgment” that supported a politics of difference, while addressing the challenges of national solidarity and the rise of immigration. Rather than putting ethnic identities on display for the consumption of a disengaged public, she argued that the festival should be organized in ways that encouraged interaction, dialogue, and friendship among individuals from different cultural groups.

I examine the legacy of Alice Sickel’s commitment to the potential of acknowledgment, focusing on specific South Asian American folk performances that take place within the context of an “India” cultural booth designed to appear as a “village home” by volunteers from the School for Indian Languages and Cultures (SILC). I argue that the progressive political potential of this performance becomes complicated when SILC’s commitment to educating people about India’s internal cultural, religious, and linguistic diversity or its colonial, global, and transnational histories is put into dialogue with the American nationalist agenda of the Festival of Nations. The conflict emerged when, in order to demonstrate the ways “India” and “Indian immigrants” fit into the American mosaic, the performers from SILC were enjoined to enact cultural practices in ways that foreground a reified sense of “Indian-ness” that was at odds with the multicultural vision of their progressive grassroots school. Given this, I engage with the work of Elizabeth A. Povinelli (2002) and Colin Bingham (2006) to ask how liberal discourses of multiculturalism may become forms of domination by calling on South Asian Americans to perform an “authentic” and recognizable difference in exchange for the good will of their fellow citizens. I argue that these sorts of demands for recognition—for the recognizable—impede acts of acknowledgment that may require more complex, contradictory understandings.

At the same time, I offer a parallel feminist reading of this performance that points toward the ways acknowledgment might surpass these demands for recognition. To do so, I examine the ways that the booth produces yet another set of tensions—those between performances of “high” Brahmin culture and local women’s “folk” culture. These tensions, I argue, become visibly productive in the performance by one particular South Asian American woman—Sheela Roy. Sitting on the floor of the “village home,” Sheela performs a daily ritual of creating rangoli, a folk art form of sand painting typically done in the doorways and courtyards of Indian homes. As she uses colored powder to make the geometric designs, she weaves for festival audiences a life-narrative. In the process, she engages particular audience members in conversation about her early experiences learning “women’s folklore,” the ways her folk practices have changed as a result of immigration, and the limitations of performing them within the festival context. In doing so she creates a women’s space for performance. This performance, I contend, is one characterized by an act of acknowledgment—creating a performance both dialogical and intimately political. I argue that through these claims for acknowledgment, Sheela refuses the constitutive and identitarian violence of the festival discourse. Her encounter with the audience creates space and time that allow the performance to exceed recognition. This case provides the first evidence that the language of actors and agency, of communicative rationality, and traditional notions of the public sphere are insufficient to encompass the political work of those whose messages are artistic and cultural, those who employ acts of acknowledgment in their efforts.