Since the horrifying terrorist attacks, things have been different … I’ve seen people whispering to each other as they eye my salwar kameez, and I know that to some of them the loose pants and long tunic seem just like the clothes of the Palestinian women we all saw on T.V. rejoicing after the attacks. Well-meaning friends have emailed warnings that I should wear only western attire, not go anywhere alone, and even buy a gun. I want to laugh off these suggestions, but I can’t. Since the attacks, too many people have faced verbal or physical abuse, been ordered off airplanes, been beaten—or even been shot to death. The other day, as I was walking into the local grocery with my sons, a man shouted, “F***ing Ay-rabs, why don’t you go home?” I hurried my children into the store, my face burning. “Mommy,” asked my younger son, “Why was that man so angry? Was he talking to us?” “What did he mean ‘go home’?” asked my older one. “We are from right here.” I had no words with which to answer them.

—Chitra Divakaruni (2002, 89)

As I write this, the tenth anniversary of 9/11 is upon us. In the decade following the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, much has changed in the United States, particularly for South Asian Americans. As Divakaruni’s quote suggests, while South Asian American community members mourned the terrible events, for many their horror was mixed with fear. In this crisis, an unfortunate number of South Asian Americans became the target of verbal insults and physical threats from both strangers and neighbors, sometimes despite lifetimes spent participating in civic activities, building local relationships, or creating community connections. Indeed, while it is certainly true that many people tried to forestall retaliatory attacks by publicly making calls for peace and community building, it is also the case that there were more than one thousand incidents of hate violence reported in the United States after September 11 that range from murder and mosque bombings to everyday harassment in public venues (Volpp 2009, 78). Most recently, on August 5, 2012, in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, a gunman with ties to white supremacist groups murdered six women and men worshiping at a Sikh temple. Clearly, the aftermath of 9/11 still resonates today, from small midwestern towns to large urban landscapes. In all these spaces, relations require repair as people struggle, among other things, to feel safe in their communities, navigate the political discourse of “home” and “foreigner,” and acknowledge one another as fellow human beings.

Here at home, South Asian Americans have responded in a variety of ways to the xenophobic rhetoric and hate crimes following 9/11. Some have taken to the streets, protesting through mass demonstrations that demand media attention. For example, in Illinois the Chicago Coalition Against War and Racism organized South Asian American activists from the Devon Avenue community to launch a multiracial peace march that drew thousands of participants. Others have protested by producing public texts that carefully document hate crimes, xenophobic rhetoric, and government programs that promote ethnic profiling.

In Washington, D.C., for instance, the South Asian Americans Leading Together has composed several documents recording hate crimes following 9/11. They then used these documents as the basis for their testimony to groups like the House Subcommittee on Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties who met to discuss the rise in racial profiling of South Asian community members. In addition, they also produced a documentary called Raising Our Voices that focuses on anti-immigration rhetoric and hate crimes pre- and post-9/11 and promoted its use on college campuses and in community groups across the country (Garlough 2011). On a more individual level, some South Asian American activists have protested on the Internet by writing blogs that reflect their personal experiences of discrimination, such as the popular New York City site politicalpoet(ry). Still other South Asian Americans have addressed the exigencies facing their communities by using theater performances, though less attention has been paid to this mode in both public media forums and academic discourse.

It also is important to remember that 9/11 was an event that resonated globally. This is evident, for example, in Frank J. Korom’s fieldwork in West Bengal, India. Here, Korom (2006) vividly describes how a popular theater group (jantra) staged a five-hour show about the 9/11 tragedy titled “America is Burning.” This performance, culminating in pyrotechnics and “a sensationalistic crashing of two cardboard airplanes … into cardboard and wood replicas of the Twin Towers” brought together Hindus and Muslims in a small town to engage with the disaster from local, transnational, and global perspectives (17). Even more interesting are the ways that this performance generated further deliberation and artistic commentary in this small community, inspiring, for instance, a local group of scroll painters (Patuas) to produce scrolls and songs about 9/11 using a traditional repertoire that reaches back centuries.

What the map cuts up, the story cuts across.

—Michel de Certeau (1984, 129)

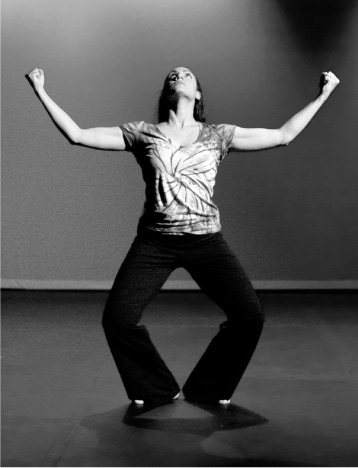

In this chapter I consider this mode of political protest, providing an ethnographic analysis of a semiautobiographical performance called Rise. This event took place at the Overture Center in Madison, Wisconsin, on a cold October night in 2005. Wielding a plunger and dancing on top of a porcelain toilet seat, Shyamala Moorty invoked the figure of the goddess in this narrated dance performance to address issues of racial profiling, xenophobic rhetoric, and hate crimes post-9/11. The theater—filled to the point of people sitting in the aisles—hosted a diverse audience from the local community that included South Asian Americans, American war veterans, UW students and faculty, as well as participants in an annual conference on South Asia.

Shyamala performing Rise. Photo credited to David Flores.

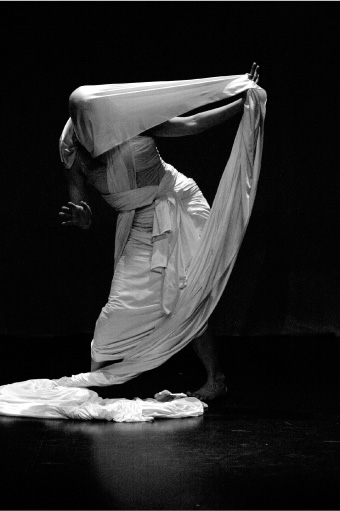

Post Natyam Dance Collective, Shyamala Moorty, Anjali Tata-Hudson, Sangita Shresthova, and Sandra Chatterjee. Photo credited to Lilian Wu.

The performance, told from Shyamala’s situated perspective as a biracial South Asian American, combined ballet and contemporary dance with a variety of dance forms important within South Asian American communities encompassing traditional folk dance, Bharatanatyam, and Bollywood styles. Shyamala’s inventive approach grows out of her membership in Post Natyam, a Web-based grassroots performance collective of South Asian American women. So, this chapter begins with a background about Shyamala’s involvement with this group and what they hope to accomplish. Together, these young women use multiple dance forms to create sites of progressive political activism through performances that simultaneously address local, national, transnational, and global contexts and concerns.

Next, I consider the political and cultural backdrop for Shyamala’s calls for acknowledgment regarding the American public sphere post-9/11. Particularly, I am interested in how and why she chooses to draw parallels between racism against South Asian Americans in the days following September 11 and a second set of violent events much less known to mainstream American audiences—the 2002 riots between Hindus and Muslims in Gujarat, India. These violent riots between Hindus and Muslims were closely followed in the international media by many South Asian Americans who watched their TVs in horror as thousands of Indian individuals were massacred or displaced from their homes. Read together and through Shyamala’s situated perspective as a second-generation, biracial South Asian American woman, the events of 9/11 and the Gujarati 2002 riots are explored in a performance that raises calls for acknowledgment as it plays with and effectively blurs the lines between “here and there,” “home and exile,” “self and Other,” as well as folk, popular, and classical culture from diverse cultural contexts.

To consider this, I reflect upon how Shyamala’s acknowledgment of her own positioning as a diasporic, biracial woman enables her to explore her lived relation to the racial, class, sexual, and national scripts embedded in both U.S. and South Asian culture. In the process, I argue that Shyamala’s performance seems to engage in an exploration of what Chandra Mohanty calls “feminism without borders.” As Mohanty (2003) notes,

Feminism without borders is not the same as border-less feminism. It acknowledges the fault lines, conflicts, differences, fears, and containment that borders represent. It acknowledges that there is no one sense of a border and that the lines between and through nations, races, classes, sexualities, religions and disabilities, are real—and that a feminism without borders must envision change and social justice work across these lines of demarcation and division. (2)

The fact that these borders both invite and prohibit potential relations is reflected in Shyamala’s artistic choices. Her performance engages her experiences of living in a world where people and art forms constantly challenge national lines.

In this process, her diasporic performance negotiates exigencies in ways that are marked by hybridity, polysemy, or incommensurability. Consequently, in my reading, I pay close attention to the ways Shyamala presents both her narrative and her body eclectically, as a transcultural site of exploration. Appropriating and transfiguring Indian and American cultural forms—from folk dances to religious narratives—Shyamala simultaneously recognizes and refuses borders in order to enact a feminist critique of violence and an ethic of care. As I reflect upon Shyamala’s work, I draw upon the feminist concept of “intersectional praxis” in order to understand how the rhetorical potential for acknowledgment is expressed through critical performances of difference (Townsend-Bell 2009).

With this in mind, my analysis of this performance then turns toward questions about the viability of “representations of suffering” in political performances. What potential lies in Shyamala’s representations beyond voyeurism? What is the relationship between truth and invention in her semiautobiographical performance testimony? In reflecting upon these questions, I consider how representations of suffering may move us to action and renew our sense of collective responsibility for the lives of others, especially those whom we view as foreigners. I also contend that the viability of representation may lead to a concern about the limits of acknowledgment. That is, if I cannot know the pain of the Other, what is it to relate to such suffering? Does our personal experience of traumatic images and stories encourage acts of identification or illuminate encounters with ourselves? What would it mean to endure the suffering of others—to hold them in our minds and remain open to the suffering—to let them haunt us and move us toward compassion toward the Other? How might Rise enact calls for acknowledgment that simultaneously awaken awareness, communicate care, and make claims for justice? To ask for such acknowledgment is to solicit a future in relation to the Other in a way that affirms the viability of difference—accounting for the fault lines that run through nations, races, religions, classes, and sexualities.

Finally, I pay particular attention to the Madison audience for this performance. To do so, I draw upon discourse from the discussion session that took place at the conclusion of the performance where audience members were given the opportunity to ask Shyamala questions about the performance and engage in a discussion about the issues at stake. Here, I am particularly interested in the ways in which Shyamala explicitly asks the audience to take upon the role of witness and participate in the political work of ethical listening and dialogue.

This request for audience participation is enacted throughout the performance, through a series of scripted inquiries and interactive dance choreography. However, it is the most apparent at the conclusion of her performance when Shyamala engages the audience in a question-and-answer session about the issues at hand, the ways that her performance addressed them, and the potential of social change and compassion. This is a critical performance technique quite similar to those used by feminist groups in South Asia at the conclusion of political street plays (Garlough 2007). Taking all of these aspects into account, I contend that the piece invites the audience into a space characterized by acknowledgment that remains open to new understandings of justice and care.

As the preface to this book describes, Shyamala and I met for the first time in San Francisco at a feminist event called “Day of Dialogue” that was organized by the San Francisco feminist group, South Asian Sisters. At this function, Shyamala performed a piece that explored the challenges facing women of color who seek to negotiate biracial diasporic identities in contemporary mainstream American society. I was deeply moved by her narrative, as were many others in the audience. I was also intrigued by her eagerness to engage the audience in a dialogue about these social issues at the conclusion of the performance, her openness to different perspectives, and the potential for compassion this seemed to create.

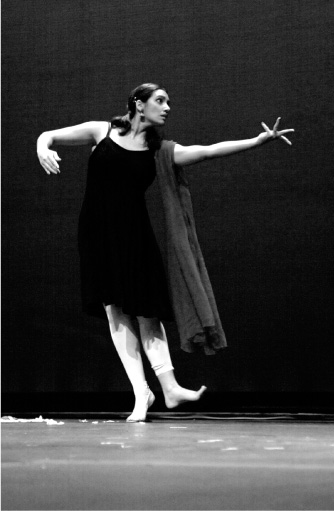

Shyamala as Artesia Strong. Photo credited to by Jen Cleary.

Over the years, Shyamala and I remained in contact, over the phone, by e-mail, and meetings at performance events, due to our mutual interest in performance and grassroots activism by women in Indian and the United States. I watched with great interest as she developed performances like Balance, Sensitize, Emblem, Potty Talk, and Carrie’s Web that challenged audiences to think carefully about feminist politics from a diasporic perspective that emphasized South Asian traditional movements, narratives, and figures. In recent years, we have read and cited each other’s academic work and visited each other’s performance rehearsals and classrooms.

Through our conversations, I learned more about her biracial background, and how she engaged with her Indian heritage through cultural forms like dance:

I grew up in the Monterey Peninsula in CA. My father was one of the few South Asians around and there were only two other families in the area that spoke Telugu (his native language from Andhra Pradesh, India). My father didn’t speak Telugu at home because my mom, and later my stepmother, were American. The few things that marked our Indianness were being vegetarian, eating South Indian food, having Indian decorations, listening to Indian music, reading Indian comic books, and visiting India a couple of times. We were not religious (my father is a philosopher), nor did we have any strong cultural practices. So, I had culture shock when I met many other South Asians in college and I learned what many other South Asian families were like. For example, I thought that arranged marriages had ended in the 1800s, and yet, I was suddenly surrounded by friends who were expected to have them.

Also in college, I started studying Bharata Natyam as a way to find a connection to my heritage. It took quite some time (many years) to appreciate the dance form and understand its beauty, which is so different from ballet (my first training and love in dance). My piece “Balance,” made in graduate school, was the first time I creatively looked at the two dance forms, their aesthetic differences, and their historic power imbalances as metaphors for both my personal identity and post-colonial politics. (S. Moorty, personal communication, January 13, 2012)

Indeed, along with a growing group of second- and third-generation South Asian American performers, Shyamala has cultivated a diverse expertise in both traditional and contemporary movement as an embodied way to understand herself from gendered, multicultural, global, and transnational perspectives. While earning an MFA in dance from UCLA’s Department of World Arts and Cultures, she trained in Indian folk dance, ballet, Bharatanatyam (where she was a disciple of Malathi Iyengar and Medha Yodh), contemporary Western dance, theater, visual art, and yoga. As such, her work situates her within a movement of women exploring the “choreography of women of color.”

Shyamala has performed as a soloist and principle dancer with the Aman International Music and Dance Ensemble (1997–2004) and the Malathi Iyengar Rangoli Dance Company (since 1994). In addition, she and Sandra Chatterjee produced a commissioned dance performance by the Brigham Young’s Folk Ensemble. As a dance instructor, she teaches courses like “Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Performance” and “Culture Jam: Theoretical and Artistic Explorations of Mixed Heritage.” Her advocacy work, which is extensive, includes being the first executive director of Women and Youth Supporting Each Other (WYSE)—a national mentorship program for young women of color to be matched with university women (www.Wyse.Org)—and serving as a volunteer with a domestic abuse NGO called SAN, the South Asian Network. Shaymala shared that her life experiences inform almost all aspects of her dance activism:

Many life experiences become a part of my work: “Balance” tells the story of my parents meeting, falling in love, separating, and in the process creating me—a hybrid. “Potty Talk” is a satirical piece where my teenage self carries her Western expectations of hygiene to India and is shocked to find that people often use water instead of toilet paper. This point of view is counter-acted by a Dalit woman character, that I researched to create, who complains about Westerners and all their paper waste that she has to clean up. Often in my work, my life events or someone else’s story lays a foundation of detail and experience, while research shapes those experiences, adding social-political context and purpose.

Much of the community work I have done is with South Asian American communities, where I simultaneously feel like an outsider and yet strangely at home. These communities include South Asian survivors of domestic violence, a Muslim American youth group and the diverse artistic community Artwallah and their arts mentorship program Youthwallah.

As all of this suggests, Shyamala’s dance performances blend traditional aesthetics with contemporary political concerns.1 That is, while the question of “authenticity” speaks in particular ways to issues of “cultural authenticity,” it also engages deeply with issues related to an “authenticity of self” (Foucault 1986). Regarding her choice to mix these elements, she offered the following in one of our interviews:

I’m not sure if I have a choice, partially because just dancing or just doing those things isn’t enough. I don’t feel interested in them, like I just used to. I felt like I was faking it. Sort of like a clown. Here I was doing these Hindu, religious dances and I wasn’t a Hindu. It didn’t feel genuine. I love dancing and it feels good. But I guess I just feel driven internally somehow, that for me as a performer, I have a sense of purpose. And for me as a performer, that purpose is driven by the things I care about. In the case of Rise, 9/11 and the riots in Gujarat hit me so hard. I thought about it for so long. I mean, I thought about for so long. I think I thought about it for a year before I did anything. It just lived in me and kind of tore me apart inside. It was my way of coming to terms with it. Or to figuring it out. Or having a dialogue with myself by performing. Or by creating work around it that was my way of figuring out what my relationship was to it. Other people might write, or journal, or paint or whatever it is. For me, this is what is going to come out now. (S. Moorty, personal communication, January 13, 2012)

Of course, Shyamala has been met with some resistance from South Asian American community members over her performance activism. Yet, there has been a great deal of support to sustain her as well. Her most significant support system in recent years has been Post Natyam—a grassroots arts collective that she helped to found in 2005. The members of this group met at the Department of World Arts and Cultures at UCLA, where they bonded through their shared experience of delving into contemporary Indian dance, theater, and video/multimedia.2 The members’ decision to form a collective grew out of many concerns. Certainly, there are always the practical ones, such as sharing administrative responsibilities that making the organization more sustainable. However, there are philosophical reasons as well.

For example, the group has a strong desire to oppose “a single orthodox approach to South Asian contemporary dance” (http://www.postnatyam.net/). Rather, the Post Natyam Collective “strives to acknowledge the complex diversity of South Asian movement forms and their migrations to multiple performance contexts, geographical locations, and bodies.” Post Natyam’s core concern involves developing a transnational choreographic process that critically and creatively engages with South Asian dance forms and aesthetic concepts. In doing so, they aspire to have “their interdisciplinary cutting edge explorations break through gender stereotypes, refuse exotification, disrupt strict dichotomies between East and West” and engage with folk and traditional arts. As Shyamala put it:

Post Natyam is a home for my hybridity. In Post Natyam I can combine post modern ideas with South Asian aesthetics and social issue topics and share them with a community that understands them all and thus can push me to make stronger work. When we first started working together (Sandra and I in 2001, and with Anjali in 2004) there were so few contemporary Indian choreographers that we had access to. We often felt pulled in opposite directions by the Western postmodern perspectives of some of our professors at UCLA vs. the more traditional stances of our classical South Asian dance teachers. Post Natyam gave us a safe laboratory to make work together that addressed our unique hyphenated realities. (S. Moorty, personal communication, January 13, 2012)

In terms of their scholarly interests, they believe, like many others, that performance and dance studies are uniquely poised to contribute to migration and global studies, as well as related topics like citizenship, territory wars, labor refugees, religions, and political occupation. Their work is related closely with that of other immigrant choreographers like Jose Limon, Pearl Primos, Hanya Holm, and Geoffrey Holder, who transform folk forms in the service of art and politics.

The mission of Shyamala and her colleagues is complex. The Post Natyam Collective seeks a transnational presence for contemporary South Asian aesthetics. The goals of the group as outlined on their Web site (http://www.postnatyam.net/) include:

1. Developing creative works, including dance, scholarship, and interdisciplinary works, that challenge aesthetic, geographic and cultural boundaries.

2. Creating and documenting new approaches to dance education.

3. Fostering an international community of artists, scholars and supporters of the arts to encourage exchange and dialogue about contemporary South Asian arts and aesthetics.

The collective’s ability to fulfill this mission grows from their diverse life experiences within the South Asian diasporic communities. It also is facilitated by the informal and formal training these women received in diverse folk and classical South Asian dance styles. Certainly cultural performances, like dance, are often an important part of everyday life as ethnic groups develop and grow. In this process, traditional culture works as a community builder—bringing people together for important events or holidays, and sometimes helping to form relationships across regional or class divides. Early in the immigration process, when local groups are small, these functions are typically organized by women and take place in home settings. Here, folk dances, rituals, and food preparation for the event are taught informally by family and friends. As the community expands, festival celebrations are often held in larger venues like community halls, school facilities, or temples and can draw up to several hundred people.

In contrast, learning traditional classical dance seems to play a different role, much more closely tied to markers of identity status or “authentic” cultural belonging. As Katu Katrak (2008) observes, “For immigrants, especially first-generation parents, the dance is a repository of cultural knowledge to be imparted to their children growing up in the United States where there exist many assimilative imperatives enticing for youth” (221). These Indian dance academies offer training not only in classical Bharatanatyam, but also diverse regional folk dances and choreography from popular Hindi movies. Depending upon the diversity of the community, participants can range from South Asian Hindus, Christians, Jains, and Muslims to girls whose families come from locations like South Africa, Pakistan, the Caribbean, Sri Lanka, or South Asia, to mainstream Americans (Leonard 1997, 135). As Karen Leonard remarks, women also play a crucial role in this context by training and costuming young women, as well as in sponsoring these performances. Typically “the performances inculcate proper South Asian female behavior, but they also express the sexuality of daughter and expand the parameters for permitted behavior in public for young women” (Leonard 1997, 136). For some families, dance is just another extracurricular activity; for others, it provides an opportunity for an extravagant, culturally appropriate public display of “eligible” daughters.

However, these early training spaces develop more than skills; they can be generative sites for artistic invention and self-discovery. Moreover, these early experiences with body movement and cultural exploration open up an understanding of dance, in general, as medium for personal development, as well as cultural discovery and creativity. As Cynthia noted,

I was born in Framingham, Massachusetts, and grew up in Houston and Southern California. Many of my childhood summers were spent with my grandparents and extended family in Taiwan. Being the child of immigrants, I constantly straddled different languages and cultures while growing up. Often I felt that I was unable to belong fully to either culture, though I have made more peace with my status as border-crosser as an adult. In fact, I often feel most at home in communities of people who have multiple, diverse belongings ….

More than anything, the “double-consciousness” of being bicultural fed an interest in dance as a way to engage with cultural difference. Nearly every piece of choreography that I have created lives in between dance forms, disciplines, cultures, or collaborators. I have also created works that draw explicitly on my cultural background: fish hook tongue investigates Taiwan’s history of linguistic colonization, while Meet me here, now—I’ll bring my then and there draws on the personal stories and cultural histories of my collaborator, Jose Reynoso, and myself. Autobiographical biographical material often finds its way into my work …

When I started to learn kathak, my discomfort with the form’s representation of gender—particularly what I perceived to be a hyperfeminine, coy, submissive representation of women—sent my radical American feminism into crisis. I found myself torn between my feminist beliefs and wanting to challenge myself to understand another worldview from the inside out. I draw on this conflict in my solo, “Learning to Walk Like Radha,” which you saw as part of SUNOH! Tell Me, Sister.

This conflict was the first step in a long, complex road of grappling with gender in Indian dance, which usefully challenged several tenets of my largely Western feminism. First, I came to understand that I had excised the performance of femininity from both my choreography and my daily life in favor of a more gender-neutral embodiment. Kathak revealed that embodying femininity can be pleasurable. I realized that not being able to perform femininity is, in fact, as oppressive as being forced to perform femininity. I learned that the technique of abhinaya enables a performer to switch between different gendered characters, allowing for a certain range of gendered performance. It also gives the performer the freedom to inflect poetic lines with multiple emotional interpretations, allowing for a degree of agency in her or his interpretation of a given script or character. Initially, my gateway to performing femininity was through the lens of bhakti, which is rooted in a spiritual movement that historically overturned caste hierarchies in favor of direct engagement with the divine. How does the submission of the female to the male resonate differently when it is understood as the surrender of the human soul to the divine? How does the performance of gender shift when the gaze between performer and spectator is reciprocal and mutually transformative, as in darshan, rather than a Mulveyian male objectifying gaze? Later, I realized that my turn to bhakti was complicit with an erasure of the secular Muslim history of the tawaif, or courtesan, causing me to question the ways I had, as a Western feminist, developed resistance to performing the erotic out of a fear of sexual objectification. This sparked curiosity about how I could perform eroticism from a position of power and agency. (Personal Correspondence)

These many worlds, however, are sometimes challenging to manage. For example, as Anjali Tata, a member of Post Natyam, noted, “When I began training in modern dance and other dance forms in college, it expanded my experience of what dance could be and prompted my initial explorations into contemporary ventures. Also, at the college level here in the U.S., my experience was that I was not considered a true ‘dancer’ because I was an ‘ethnic’ dancer and not trained in the mainstream concert forms of Modern or Ballet.”3

Sandra Chatterjee, another member of the collective, takes this desire for fusion and invention a step further. She states, “I think it was primarily audience reactions to Kuchipudi performances outside India, where I felt exotified, that encouraged me to respond to the audience reactions through dance itself. I began studying Western contemporary dance, but I soon realized that simply fusing Western contemporary dance with classical Indian dance did not solve my dilemma. Studying Polynesian dance while at the University of Hawaii, I fundamentally changed the way I perceived my own body. That experience in addition to intellectual engagements prompted my first ventures into contemporary choreography.”4

Sangita Shresthova, a fourth of the five members of Post Natyam, concurs when reflecting, “While I value and cherish my classical training (in Bharatanatyam and Charya Nritya), I have always felt a disjuncture between my own fractured cultural experiences as a Czech/Nepali, my life defined by a state of permanent in-betweenness, and the world of completeness perpetuated in my dance training. My ‘contemporary’ work grew out of a necessity to reconcile these schisms.”5 Similarly, Shyamala’s approach to diasporic dance performance is significantly informed and also complicated by her biracial identity. In an interview she commented, “The fact that I have both South Asian and European heritages generally gives me fairly comfortable inclusion into both groups on the surface, until I am called out and made unwelcome for not being enough of one or the other.” Such demands for “authenticity” in performance or displays of “cultural competence” are not uncommon, and this is what makes Post Natyam a particularly important space.

Certainly, Post Natyam is a unique organization in many ways. Most striking, however, given their transnational focus, may be their “location” in the virtual. As members of the group are currently living across the globe, from Los Angeles to Munich, getting together to collaborate is difficult. To find a solution, the members decided to attempt working together via the Internet. As Cynthia notes, “Because we are physically scattered across continents and are not often able to gather in a studio, the Post Natyam Collective decided to experiment with using the Internet to collaborate artistically towards the end of 2008.” This online collaborative process, which has included giving assignments to one another, posting videos, and providing feedback, is centralized on this blog in the hopes of “inviting a larger public dialogue into our process” (personal interview, January 2012). Throughout the year, these performance pieces are staged in diverse international locations. In this way, local, global, and transnational concerns are “launched into dialogue” as different audiences respond to the situated events.6 In addition, the group presents their work in other forms that “travel” such as dance-for-camera-videos, scholarly articles, art books, and installations.

Post Natyam on Skype, left to right, from top, is Anjali Tata-Hudson, Cynthia Ling Lee, Sandra Chatterjee, and Shyamala Moorty. Photo courtesy of the Post Natyam Collective.

This inventive arrangement has been the type of work that sometimes escapes the notice of folklore scholars, particularly those who are not as interested in exploring the ways that folklore intersects with fields like cultural studies or communications studies. As Trevor J. Blank (2009) notes, “When the World Wide Web took off in the 1990s, the allied disciples of anthropology, sociology, and communication studies began paying careful attention to various sociocultural dimensions of the Internet, but amid this dialogue only a small handful of thoughtful folkloristic articles on the burgeoning Internet culture appeared (Baym 1993; Dorst 1990; Howard 1997; Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1995, 1996; Rouch 1997)” (3). While the Internet is often considered from the perspective of mass culture, it also is an important storehouse and a vital system for the transmission and creation of folklore in small groups (Bronner 2002; Dundes 1980). In my opinion, I believe it is crucial that this work continue to deepen as it provides new ways to understand folklore’s disciplinary givens, contemporary subjects, and increasingly transcultural texture. It opens up new ways to understand performances like Shyamala’s that are collaboratively produced, are global in nature, and can be productively approached from several disciplinary standpoints.

Post Natyam’s collective structure and communication over the Internet also allows members to share teaching methodologies and offers an inventive South Asian contemporary dance curriculum. Within their lectures, master classes, workshops, and residencies, members focus on a diverse set of traditional and contemporary South Asian technique, including Bharatanatyam, Abhinaya, Navarasas, Kathak, and Kuchipudi, as well as Contemporary Indian Dance, Dance-Theater, Music-Dance Collaboration, and Text-Movement Improvisation. In addition, the collective offers theme-based courses that are linked to current Post Natyam projects such as “The Politics of Femininity,” “Meet the Goddess,” “Erotics Rerouted,” “Indian Dance in Transnational Contexts,” or “Hybridity as a Creative and Theoretical Perspective.”7 For example, in terms of “Meet the Goddess,” Shyamala notes:

To me the idea of the goddess is an iconic image that needs to be questioned even as it is invoked. In our show “Meet the Goddess” the Post Natyam Collective members each examined our relationship as real women to iconic femininity in Hindu mythology. Powerful figures like Durga, Parvathi, Kali, and Saraswati are given a power and reverence that contrasts hugely with how real women are treated under the patriarchal values of mainstream Hindu society.

The section of Meet the Goddess that I created, “Sensitize,” was about female desire, acknowledging it and giving it a space to flourish. I was making woman the subject rather then the object of the male’s gaze as Laura Mulvey has theorized in her ground-breaking article “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” For this piece, I was drawn to the image of ardhanarishvara, the half male, half female god/dess. But even as it reaches toward equality, it isn’t always the ideal—what if the couple is same sex, or if there is more than one partner? In “Sensitize,” the issue remains unresolved and the woman’s desiren is left unsatisfied when the temporary union is over too soon. (S. Moorty, personal communication, January 13, 2012)

Most recently, their online work has focused upon a central project that contains three major threads: (1) the use of Internet-age technologies; (2) the figure of the courtesan in the Indian subcontinent; and (3) community work with survivors of domestic violence. As Shyamala notes,

Shyamala in SUNOH! Tell Me, Sister. Photo credited to Michael Burr.

While we’re interested in the courtesans of the past, we’re also interested in the stories of real women today, especially stories of resistance and healing. Cynthia and I have been honored to be a part of such women’s experiences through the South Asian Network (SAN). I have been facilitating workshops for their support group for women who have faced emotional and physical violence or sexual abuse. In these workshops, I have concentrated on stress relief through yoga and self-expression through writing. (S. Moorty, personal communication, January 13, 2012)

In the process, she has worked with individual survivors of physical and sexual violence to create performances using dance as a therapeutic or creative rite to witness the abuse they have undergone.

Shyamala in SUNOH! Tell Me, Sister. Photo credited to Michael Burr.

Along these lines, in the spring of 2011, Shyamala and Cynthia did a national tour to perform material from SUNOH! Tell Me, Sister that features new multimedia collaborations. The performance uses multimedia and contemporary Indian dance theater to bring to life “women’s stories of being silenced, finding voice, and the importance of sisterly community. The work draws on the stories of contemporary South Asian survivors of domestic violence, the performers’ own experiences as contemporary women artists struggling with tradition, and images surrounding the courtesan/dancing girl of the Indian subcontinent” (http://www.narthaki.com). The show reflects Post Natyam’s long-term community work with AWAZ, the South Asian Network’s support group for women survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, or harassment. Using dance “on a continuum of tradition and innovation, theory and aesthetics, art and activism,” this latest performance showcases the potential of performance as powerful politics (http://www.narthaki.com).

Without question, Shyamala understands her artistic performances as practices of political intervention that create public forums, inviting discussion and encouraging deliberation. This is the case both when her performances contain overtly political content and when the political material is more covertly delivered and simply engenders a critical stance from the audience. To her, cultural performance is understood as a critical practice and agenda-setting tool that provides an opportunity to recognize silenced voices. Of course, all this political work does not necessarily lead to progressive change, regardless of intent. Each event only holds potential. Nevertheless, like other performance activists, she believes the stage serves as a powerful site for political action, even if the changes are small.

Shyamala has performed Rise in a variety of settings, both in the United States and abroad. And in each new context, she strategically varies the form and content to meet the demands of the cultural, social, and political backdrop, as well as the audience composition. Rise is a one-woman show that tells the story of an Indian American woman, Shakti. While her husband is visiting Gujarat, India, riots between the Hindus and Muslims erupt and Shakti becomes increasingly anxious about his well-being. The situation also has deeper resonance because Shakti is Hindu and her husband is Muslim and their families have had disagreements in the past regarding religious issues. To compound her upset, Shakti turns on the TV and is bombarded by news stories about 9/11. Overwhelmed, she sits on her toilet, only to find it is plugged. In the rest of the performance, a series of characters “rise” out of Shakti’s toilet to tell their stories of violence and comment upon the pollution of humanity due to political and religious divisions. To answer these exigencies, a secular goddess emerges—symbolized by the River Ganga—to mourn the dead and cleanse the world of this violence.

Not surprisingly, Rise was a successful endeavor from the first performance and acclaimed a “Tour du force” by the Los Angeles Times. Consequently, in 2005, as the chairperson for the thirty-fourth “Annual Conference on South Asia” I was pleased to have an opportunity to bring Rise to the UW Madison campus. Typically, the conference’s evening entertainment is comprised of folk and classical performances by internationally renowned musicians. However, this year I was interested in providing a performance with a focus on social justice. One that took into account human rights concerns related to gender, generation, religious affinity, economic class, and immigration—one that would offer our community, and conference members interested in South Asia performance and politics, a chance to explore together the issue of 9/11 and the Gujarati riots.

Shyamala. Photo credited to David Flores.

Certainly, the horror of September 11 and the subsequent U.S. bombings in Afghanistan have led to difficulties for South Asian and Middle-Eastern people.8 Indeed, even model-minority South Asians have been subject to “racial profiling.”9 Consequently, many post-9/11 South Asians have found themselves in a difficult position—wanting to mourn the terrorists’ victims, while simultaneously denouncing the violence against South Asians.10 In the midst of national crisis, public mourning often provides the grounds for nation building. By mourning the dead together, we affirm our civic connectedness—constituting our “we.” As Derrida (2001) argues, mourning is not only related to the political, but arises out of the political because through its rites and rituals it opens up the possibility of a political space and relationality (19). However, while many Americans were able to publicly mourn the losses of 9/11, many South Asian Americans felt they were denied civic participation, because they were figured as “the Other.” Thus, for many South Asian Americans, the loss of 9/11 became a double loss. Moreover, in the years following the attacks, many South Asians—particularly Muslims—reported feeling “unsafe and insecure” in the United States because they feared incarceration en masse in internment camps (like those that held the Japanese after Pearl Harbor) or expulsion from the country. As Cainkar aptly notes, “These fears did not seem unfounded as communities watched thousands of Muslim noncitizens deported for visa violations, nearly a thousand jailed for long periods of time without charge and tens of thousands interviewed by the FBI and hundreds of thousands watched” (3).11

Sadly, not long after 9/11, another set of violent events rocked the South Asian American community. In 2002, between February 28 and March 2, the Sabarmati Express train was stopped at Godhra, a town in the Panchmahal district of Gujarat (Dugger 2002). This town has suffered from a long history of communal (i.e., religious) tensions. During the stop, a fire broke out in Coach S-6 of the train. This resulted in the death of fifty-nine people. Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi, and others belonging to conservative Hindu nationalist organizations, alleged that the Godhra tragedy had been a preplanned Muslim conspiracy to attack Hindus, weaken the economy, and undermine the state (Coalition against Genocide 2005).

In response, Hindu nationalists called for a bandh (a general strike), to take place on the following day. This act was condemned by human rights organizations because bandhs are frequently associated with violence, and consequently have been made illegal. However, the Government of Gujarat, led by Modi, endorsed the strike. The attacks that followed prompted retaliatory massacres against Muslims on a large scale. Between February 28 and March 2, thousands of people, mostly Muslims, were killed in Gujarat. Following this, thousands more were internally displaced. According to independent human rights observers, the events in Gujarat “meet the legal definition of genocide” and a climate of uncertainty permeates civil society in Gujarat even today (Coalition against Genocide 2005).

The response from South Asian communities around the United States was complicated. Many “anti-communal” NRI organizations from New York to San Francisco rallied to decry the violence and the government’s response in terms of the murder and displacement of thousands of Indian Muslims and Hindus. Other NRIs supported the Hindu nationalistic government of Gujarat. As Gayatri Gopinath notes, this situation provided “a stark illustration of the double-sided character of the diaspora” (2005, 196).

For Shyamala and I, these two events, taking place oceans apart, were connected by religious fundamentalism, acts of terror, and community disintegration. The script and choreography of Rise were meant to address these exigencies and invite the audience to consider these events from alternative vantage points.

That night the Madison performance of Rise took place on the Rotunda Stage at the Overture Center on Saturday, October 8, 2005. The performance space was overflowing and audience for the event was diverse, as advertisements had been sent to many different South Asian organizations, posted in Indian grocery stores, and advertised with student organizations, as well as publicized in the South Asian Conference literature. More interesting was the unexpected inclusion of American war veterans who, by chance, became a part of the audience after attending an event at the Wisconsin Veteran’s Museum located near to the Overture Center.

Before the performance began, Shyamala walked around the auditorium talking to audience members distributing flyers that described her background as a public intellectual, educator, and performance artist. The flyer also included notes and references for the audience regarding the material that inspired that show. For example, Shyamala explains that her character of a Dalit cleaning woman was partially inspired by the article “The Stink of Untouchability and How Those Most Affected Are Trying to Remove It” by Mari Marcel Thekaekara (2005) in the New Internationalist Magazine. In addition, a portion of the Hindu politician’s discourse is partially quoted from the former chief of the R.S.S. (Rashtriya Swayamsevek Sangh, a Hindu nationalist organization) and the Muslim politician’s text is partially inspired from the poem “Waa Ahl Gujarataah” by Ha Moslimat Hodi. Shyamala also reveals that the sound bites of the American politician are from George W. Bush, taken from CNN broadcasts. Providing this context to the audience is part of her “critical approach” to performance advocacy.

The performance begins with a blank stage. A single spotlight appears, illuminating Shyamala sitting on a toilet while reading a newspaper. Her hands shake as an audio montage blares out political and religious rhetoric from American and Indian media sources. Media that serves to fuel divisiveness and terror. The rhetorical force of this montage lies in the eclecticism of its parts. Through it, Shyamala directs the audience’s attention to the work of managing public meaning and memory as they focus on her choice, assembly, and unexpected juxtapositions of media fragments. In doing so, she foregrounds complicated relationships between peace and war, friend and enemy, citizen and stranger, or victim and attacker. The force of this eclectic play with images lies precisely in its incongruity, its deviance, and the tensions integral to the relationships it proposes. In this process, political discourses and representations are brought into conflict, so that contradictory relationships (or incommensurabilities) are foregrounded and made visible.

In this way, the play of this montage can be understood through the notion of “hermeneutical rhetoric” (Jost and Hyde 1997). Put simply, by this I mean “hermeneutical rhetoric” involves the ways idioms, styles, and premises from the past are made meaningful in cultural practices, offering up emotional values that function as rhetorical capacities and constraints. As Eric King Watts (2002) argues, “The emotions attune us to the character of communal relations and to the significance of others and of their pursuits. Practical wisdom requires more than calculative thinking; it demands a sort of reflexive openness to the possibility of placing oneself in a productive relation to the other … it works through an aesthetic praxis that moves people to the places in which to find the right words to touch others” (22). It is the site where the ideas and aesthetics of past discourse are interpreted for contemporary rhetorical situations (Garlough 2007). Through this media compilation, Shyamala signals to the audience that her performance is entering into a dialogue with popular discourses in the public sphere (Bakhtin 1990; Garlough 1997). In doing so, she makes us hear the words differently.

In the next scene, Shyamala gracefully dances with the American flag, simultaneously honoring it, evoking predatory eagles, and wrapping it around herself to suggest a loving caress. It also suggests the ways that many South Asian Americans in towns all across the country, like Madison, struggled against racism by performing signs of allegiance to the nation, such as displaying the American flag. This served both as a protective device and also, for some, as an “affirmation of their future in the United States” (Grewal 2005, 212). As Robert Hariman and John Lucaites (2002) point out, abstract forms of civic life—citizenship or patriotism—have to be filled in with vernacular signs of social membership to provide some basis for identification (365). It is not surprising then that during the aftermath of 9/11 many South Asian Americans chose to display the flag as a sign of their civic engagement and love for their country.

Yet for others, such a display felt disconcerting. As Chitra Divakaruni, a popular South Asian American journalist, writes: “I’ve been advised to display the American flag prominently on my house and car. This upsets me in a strange way. I love the flag, just as I love America and its commitment to liberty, equality and justice. But it bothers me that my patriotism is suspect unless I put up a flag to demonstrate it. And why? Because I don’t fit the public’s notion of what a ‘good American’ looks like” (2002, 89). Divakaruni’s ambivalence about publicly performing “good” citizenship and displaying the symbols of American patriotism calls attention to the violence of having one’s home made foreign to us (Das 2007).

This sentiment seems to resonate in the closing moments of the dance as Shyamala rips the flag off her body and plunges it down the toilet—the singular prop placed center stage. This leaves many audience members shocked, particularly the American war veterans who are watching from the balcony above. At the very least, most audience members seem to struggle as they attempt to interpret these acts. On the one hand, they seem to function as a rhetorical means of addressing a diasporic experience of alienation and disacknowledgment. How can one express the experience of being made to feel a stranger in one’s home or a foreigner even when one has American citizenship papers?

On the other hand, Shyamala also seems to propose that the toilet and the waste inside symbolizes the waste of fundamentalist rhetoric—both religious and political. The flag becomes part of the abject horror of death infecting life (Kristeva 1982, 3). Her performative act challenges audiences and draws attention to the deep rules of citizenship that prescribe specific interactions among citizens in public spaces. It is a moment in the performance that resonates with both potential and threat. It provokes. For many, seeing the American flag in a toilet is an incommensurable image. Thus, through this dance, she raises a radical set of questions. They are questions that maintain a disruptive force and embrace uncertainty. And, in allowing the question to remain there, she accepts a certain amount of risk—the risk of being wrongly understood, wrongly interpreted, demonized, or interpreted too soon. In an interview, I asked her to comment on this choice:

CG: When you envisioned the plunger and the flag for your performance, what did you want those images to evoke for your audience?

S: I did realize when I made it that it was a pretty intense statement. Originally, I had everything coming out of the toilet only and my director asked why does the toilet overflow in the first place? What is all the garbage and the mental waste and the rhetoric that causes it in the first place? And that’s how the flag came to be pushed into the toilet. It was about rhetoric. It was about these huge statements that are being made and the way the nationalism and patriotism, in the case of Iraq and in particular 9/11, are a part of that. The moment (the flag) gets tossed in the toilet, the main character asks what is that nationalism used for? For her, she just can’t deal with it. So what does she do? She flushes it down the toilet.

The whole dance with the flag is about an eagle, a predator. But also there is a moment where I hide in the flag or take refuge in it and evolve to other things. And the Katrina image is what I had in mind.

CG: That’s what is really useful about images. They can be recycled. Different people use them for different reasons. That particular image has been used over and over again.

(S. Moorty, personal communication, August 16, 2007)

Next, as described in the introduction of this book, Shyamala engages the audience with a personal testimony—the story of a hate crime that happened to her after 9/11. She was walking down a local street when she encountered a man watering his lawn. Although she smiled at him warmly, he gestured and angrily aimed his gardening hose at her, attempted to douse her with water. Humiliated and afraid, she left feeling like a stranger in her own community. As Hartman (2006, 254) writes, personal testimonies like these provide “histories from below,” filling in the gaps of mainstream discourse in the public sphere. Not only does testimony provide accounts of violence, but it attempts to put us in the individual’s place, or at least in their presence, drawing the listener in to the experience of suffering and fear. In this way, these testimonies remain personal and subjective, even while they are shared.

Shyamala uses this narrative to point toward a question. Why did hate crimes against South Asian Americans soar by 1,600 percent immediately following the disaster—as a barrage of media images and stories directed our gaze toward a devastated lower Manhattan, the bodies of victims, the testimony of witnesses, and the grief of those who lost loved ones? Across the United States, South Asian Americans, misrecognized as “terrorists,” were beaten with baseball bats studded with nails, attacked in their places of work and worship, violated verbally with racial epithets, and frightened by death threats (http://www.saalt.org/). Moreover, given the “rally around the flag” phenomena that characterized most mainstream discourse, reports of this violence were not prevalent in the public sphere, and were generally unacknowledged by the wider American population, even by many South Asian Americans.

The deeply personal character of these life stories allows them to “touch heart as well as mind [appealing] to a human commonality that does not imply uniformity” (Hartman 2006, 254). Further, the testimony Shyamala offers is deeply relational. As she speaks to audiences about the ways in which she has been wounded, the wound itself bears witness. Consequently, this testimony is addressed to a double recipient. That is, this testimony is addressed not only the audience of listeners but also to Shyamala—the survivor/narrator who is providing testimony, whose sense of identity has been shaken, and who must relive her victimization through her performance of the initial experience of violence. As audience members see Shyamala slip into “back there,” the emphasis shifts from the perpetrator’s behavior to the humanity of the victim (Hartman 2006, 257), thereby encouraging us to acknowledge the victimization they have experienced.

Of course, not everyone wants to hear this story or feel her pain. She is performing as a parrhesiastes—speaking at great risk, in front of an audience where power relations are unbalanced, freely confessing the truth of her experience, although the threat of retribution is quite real. In doing so, she discloses something of herself and the truth of what she believes (Foucault 2001). The everydayness of such personal stories makes apparent the relation between violence and the humanity of the Other (Levinas 1981). It communicates what is precious and injurable and enacts calls for acknowledgment. To ask for such acknowledgment is to solicit a future in relation to the Other. That is, Shyamala’s testimony evokes a pathos of pain, calling attention to the ways that performances of suffering may inform acknowledgment (Das 2007).

Next, in Shyamala’s performance, she explodes into a dance that combines both ballet and Bharatanatyam simultaneously, demanding from the audience recognition for multiple ways of realizing a South Asian American identity.

Shyamala, Half Ballet, Half Bharatanatyam. Photo credited to David Flores.

Split down the middle, her right side presents a graceful ballet form, her left side artfully displays traditional Bharatanatyam dance movements. Here, gestures have complex and layered uses, expressing the ntta vocabulary (and movements that also traditionally convey stories and legends from the Indian epics and folktales). In addition, gestures render the emotional states of the characters being represented (Katrak 2004). As Katrak (2008) observes, “A solo female dancer (in the traditional form) communicates stories and emotions via a wide range of gestures: expressive, representative, and emblematic” (218).12 Shyamala combines these styles to explore her own biracial identity and create an awareness of diversity within the South Asian American community. As the dance grows to a fevered pitch, Shyamala begins to eclectically mix these movements and deliberately falls off balance. Shyamala’s combination of disparate traditions requires a multifaceted fluency—a cultural competence that combines “East” and “West” in complicated ways and widens the category of South Asian diaspora from within. It is both a personal and political commentary on strategic identity presentation.

In each of these scenes, Shyamala’s performance engages in intersectional praxis. Intersectionality—first coined by Kimberle Crenshaw (1989)—is a feminist approach to political discourse and research that at its most basic level suggests the ways that race oppression and gender oppression interact in women of color’s lives (Knudsen 2005, 61). Scholars employing this approach focus upon analyzing how social and cultural categories of discrimination—based on gender, race, ethnicity, age, disability, sexuality, class, religious orientation, immigration status, and nationality—interact on multiple and simultaneous levels. The outcome of this interaction is systemic inequality.13 By evoking the image of streets cutting through one another, intersectionality calls attention to the ways individuals live with multilayered identities and may be members of many communities simultaneously. These identities, derived from social relations, history, and the operations of power, may sometimes be at odds. Consequently, people may simultaneously experience oppression and privilege.

While intersectionality was originally guided by liberalism and Marxism, more recently it has been influenced by postmodern theoretical approaches that range from discourse theory, deconstruction, queer theory, and post-colonialism (Feree 2009). Consequently, intersectionality has been adopted by a range of disciplines from anthropology to sociology. Feminist scholars interested in folklore, for example, have found this approach useful when studying the everyday practices and performances of women through the intersections of social and political forces, as well as personal, psychological, emotional, and physical characteristics that undergird the relationships and values they communicate through folklore (Garlough 2007, 2008; Mills 1991; Sawin 2002). As Martha C. Sims and Martine Stephens (2005) point out, “Scholars who are interested in intersectionality frequently focus on oppressed or under-represented individuals or groups, those who have been excluded, ignored, or discriminated against by mainstream groups—in other words, those who have been pushed to the margins” (199). This perspective provides a framework for folklorists to discuss the dialogic interplay between performance contexts, as well as the ways power within social contexts operates to influence those texts and performances.14

However, scholars are not the only ones who have used the concept of intersectionalty in their work. Activist efforts by women, like Shyamala, who are interested in social justice issues also often display an “intersectional praxis” (Townsend-Bell 2009). These grassroots activists use intersectionality to provide a critical lens for bringing awareness to social justice endeavors and interventions on the ground. For instance, this might occur when grassroots activists are involved in a case where ethnicity, gender, and class work together to limit access to social goods such as employment or fair immigration.

Erica E. Townsend-Bell (2009), drawing from a political science perspective, argues that intersectional praxis, like Shyamala’s has two requirements. The first is a commitment to a politics of accountability that would assist in the elimination of oppressive relations (2–3). The second requirement is that activists should pay attention to the impact and role of difference in their political work. She labels this “intersectional recognition.” Intersectional recognition, she believes, should grow from the group’s own experiences. It also should provide the grounding for continuing education on what differences are relevant to the problem at hand and an acknowledgment of the ways these differences relate to each other.

When applying this framework to Shyamala’s performance, we see something interesting about the form this recognition takes. That is, certain acts of recognition perpetuate beliefs that a collective identity is fixed. These identities, often based upon notions of “authenticity,” emphasize differences between groups and the homogeneity within them. They are identities that reference their own stereotypes and classify people in reductive ways (Phillips 2007, 31). These representations often are not emancipatory, even when used by in-group members, because they work, sometimes inadvertently, to constrain individuals and keep them on the margins of society (Hall 1997).

In contrast, Shyamala’s dance resonates well with something Greta Snyder (2011)—drawing from cultural studies literature—has called a politics of “multivalent recognition.” Here, participants demand recognition for multiple ways of realizing a collective identity. Put differently, actors engaged in the politics of multivalent recognition use demands for recognition to create an awareness of the diversity within a category (Schiappa 2008, 114). This type of recognition does the critical work of calling attention to the ways that recognized identities can sometimes reinforce reductive visions of collective identity. Snyder (2011) argues that four features of this type of recognition are (1) it works to highlight the visibility of marginalized groups; (2) it tries to widen the category from within; (3) it is a strategic identity presentation developed with the awareness that this representation is political and with a sense of the historical backdrop against which the representations are interpreted; and (4) calls for the cultivation of different and contradictory visions of this identity (15–16).

Critical play with recognition is an important part of the intersectional praxis that occurs in activist performances, like Shyamala’s, particularly when interrogating the complicated and sometimes contradictory representations advanced by diasporic activists in political contexts. However, I believe simply focusing upon the impact, role, relevance, and relationships between identity differences does not do justice to the sort of activist performances that Shyamala works to invent and facilitate. Rather, her approach takes into account more than recognition of identities and their complex interrelationships. It goes beyond focusing simply on claims for individual or abstract rights and the consistent application of the latter to the former. Her choice of medium is based on a desire to develop a context that also places a premium on valuing attentiveness and responsiveness, as well as the building of trust and an ethic of care.

For this reason, I believe that Townsend-Bell’s second requirement—intersectional recognition—would benefit from being reconceptualized, so that recognition and acknowledgment are not used interchangeably. Instead, I would like to deepen the ways that acknowledgment is conceptualized in order to understand the ways it may work to generate the potential for an ethic of justice and care in activist performance contexts. That is, chapter 1 provided readers with a sense of what acknowledgment is. In this chapter, I am most concerned with illustrating how acknowledgment operates rhetorically in performances. Most specifically, how the performers’ intersecting “ways of being” argue for caring relations within communities, as well as with distant others. How might performances encourage self-care? How might performances persuade audience to more ethically acknowledge those who are strangers or very different from themselves? How might an audience be encouraged to acknowledge their own need for moral responsiveness in their communities and the world at large? How might these performances serve the goals of citizenship in ways that exceed the goals of recognition and inspire careful judgment?

For example, reflecting further on intersectionality in an interview with me, Shyamala stated,

S: I put together this dance piece in Rise out of my own physical confusion and that physical confusion being a metaphor of course for who I am.

CG: How are you feeling when you do it?

S: When I did it in the beginning when I first created it, it was very difficult for my body to do and I was really trying to figure out the energy. There is a real energetic difference between the two. With the downward energy versus the upward energy and in the beginning I really felt the confusion and the difficulty and it was more of a stressful piece to do in the beginning and now it’s easy.

CG: So when you do it, does one sort of take over the other or is it balanced?

S: I work to keep them at a pretty good balance; it’s interesting because I feel that ballet is more in my past than in my present. So there is definitely more of a sense of ease, or a sense that it’s okay for me to be doing this movement, and that’s what my body does now. Versus when I do ballet, there is a little more insecurity there.

(S. Moorty, personal communication, August 16, 2007)

This multivalent representation works through eclecticism, rather than synthesis, cultural syncretism, or pastiche (Delgado, 1998; McGee 1990) in order to juxtapose apparently unrelated fragments. At its core, the notion of eclecticism directs our attention to the work of managing meaning. As a method of creating discourse, eclecticism addresses such epistemological concerns by directing the choice, assembly, and rearrangement of elements into texts, such that they manifest unexpected juxtapositions and disjunctions. In this process, culturally accessible forms and logics are carefully organized so that a contradictory relationship is foregrounded. Indeed, the force of the eclecticism lies precisely in its incongruity, its deviance, and the tensions integral to the relationships proposed. As such, eclecticism, I argue here, should be understood as a deeply rooted type of hermeneutic and rhetorical strategy and practice where the ideas and aesthetics of past discourse are interpreted for contemporary uses in rhetorical situations.15 Eclecticism provides diasporic individuals in these complex social conditions a means for flexible transformation that has facilitated the coexistence of rich and historically diverse cultural traditions.

Shyamala’s performance is extremely reflexive—drawing attention to itself as art, deferring meaning, and challenging assumptions of an easily consumable “multiculturalism.” Her body in this performance presents a diasporic way of being through a refusal to speak or communicate within a single cultural or rhetorical competence. Through eclecticism, this performance calls attention to the ways that hybridity—though fashionable in cultural theory—is not always easy to live. As Sunaina Maira (2009) suggests, “social institutions and networks continue to demand loyalty to sometimes competing cultural ideals that second generation youth may find difficult to manage. For many, liminality is an ongoing daily condition of being betwixt and between cultural categories.” She goes on to argue, “The performance of a visibly hybrid ethnicity occurs in specific contexts and is not always optional; it belongs to a range of performances and cultural scripts in everyday life” (Maira 2009, 301). Shyamala echoed these concerns in an interview with me, stating:

CG: The question of responsibility and representation … How do you negotiate that?

S: It’s interesting because in the making of this piece, at some points I was tempted to make it more simple, and just represent a Hindu. My director, who is also of a mixed background, was like, “no way.” It’s so important that that existed and, and was part of the equation and dialogue. That’s what was so difficult.

CG: Why was it so difficult?

S: It felt like her identity was so confusing in the first place and I didn’t want that to take over the piece because it was about all these other things.

CG: What helped you to negotiate the sticky spots?

S: I guess I do identify with the words like hybridity, multiplicity, and multiple heritage. I don’t like to think of it as biracial so much because I feel like there aren’t just two things in there anyway … I feel like if you’re thinking about hybridity or multiple heritages, it really expands into a whole other group of people, nearly everyone in one sense or another. Because I’m living in a society where you can get Italian food on one block and the hybrid version on another. And we’re all affected so much by each other, whether we know it not, that I think I like a more open term like that.

(S. Moorty, personal communication, August 16, 2007)

Clearly, Shyamala’s performance transgresses expectations by not conforming to traditional categories. Moreover, the fusion represents for the audience how she is kept off balance by her identity. In the process, Shyamala’s critical play with dance calls into question the constitutive power of stereotypes and makes visible how these stereotypes work to exclude South Asian Americans. It strategically performs the uniqueness of a diasporic identity and uses that distinctiveness to make claims for an intersectional recognition that embraces diversity within the broader group constituted as South Asian American. Again, as I mentioned previously, these acts of testimony shift the focus of attention from “what” people are (i.e., immigrant, citizen, American, South Asian) to “who” they are. When humanized, each person’s story is understood as unique, thus contesting simplistic representations.

In refusing to make essentialized claims about recognition, the dance works not by telling people what to think, but by asking them to think. It accepts the risk of being wrongly interpreted and addresses the questions of recognition in a way that suggests South Asian American identity is not a puzzle that can be resolved definitively one way or another. South Asian American identity, like all diasporic identity, is more or less permanent aporia—an undecidable within diasporic and national discourse. Her dance performance suggests to audiences that we must live within the uncertainty that these questions pose. We must learn to develop a heightened sensitivity to the complexity and undecidability that haunt and disturb reflections upon South Asian American identity, while maintaining our vigilance about the particular ways this aporiatic identity may threaten the groups’ ability to act collectively. This dance also raises the question of who may be included in the category of a 9/11 victim, opening the limits of a publicly acknowledged field of appearance.

I am an ocean of sorrow,

a cool stream to rinse away the hate,

a drop of hope,

I am a watery grave …

where all will, and must

find peace.

—Line in Rise spoken by the Goddess

So, given these critiques, what can be done in the name of care and social justice? Throughout this performance, Shyamala makes claims for the potential of the figure of “the goddess” to heal our communities and work toward peace. Indeed, one of the first dance pieces in Rise gestures toward folkloric aspects of a daily puja—one dedicated to a universal manifestation of the goddess. In an offering of welcome, Shyamala scatters red flower petals on the stage. It is a public form of devotion and dedication that can be read as a traditional “womanly” manifestation of care.

Interestingly, this call to the goddess is later evoked by Shyamala as she plays the part of a little Muslim girl whose mother has died violently in the Gujarati riots. The goddess takes the form of the child’s favorite doll. And the girl explains to the audience, “My doll’s name is Ganga. I call her that after the river Ganges. Isn’t she perfect for a river goddess, all dressed in blue? I read about her in a comic book. She heals and purifies.” Certainly, this turn in the plot is not intuitive, given what the performance has just revealed about the complexities of communal violence. However, as Shyamala demonstrates, the meaning of “goddess” is not fixed. Rather, the goddess is a multivalent symbol associated with a rich set of meanings that might be strategically employed for rhetorical purposes. Through this surplus of meaning, Shyamala advocates peace and a women’s centered spirituality. Here Ganga is refigured as a universal force of nature—a purifying force that cleanses the pollution of humanity. As Shyamala puts it, “The innocence of a young girl has allowed her to embrace the goddess anyway. It is her determination and hope that can help to create a transformative force beyond our human tendencies for revenge. The goddess is merely a symbol of higher consciousness or a natural force beyond humanity or a revolutionary state of mind. It is not that I think a Hindu goddess is the universe.” At the conclusion of the performance, Shyamala transforms into this “fierce goddess.” This entity seeks to help the audience mourn the nonsensical violence, embrace social justice, and begin the work of repairing the communities and lives that have been torn apart.

Many South Asian feminist scholars, like Elizabeth Gross, have argued that the Hindu pantheon may offer powerful resources to reimagine and connect with a female power for women in religious traditions that do not have goddess figures (Gross 1983, 217). Conversely, others, such as Rachel McDermott and Cynthia Eller contend that it is not only difficult but sometimes culturally insensitive to appropriate goddess traditions. Shaymala, aware of these concerns, disclosed in an interview:

In making Rise, when the idea for using the goddess arose, I was interested in what Ganga/the Ganges can represent: cleansing, or literally plunging, away the filth of human prejudice and intolerance. Of course, using a Hindu goddess is tricky when dealing with religious conflict, and yet developing tolerance and justice doesn’t mean erasing religion or religious differences. So, in Rise I call on the goddess but bring up her contradictions and adapt her to allow space for other interpretations. She rises out of the toilet, so the intrinsic idea of purity is questioned right away. Her weapon is a plunger, which is slightly humorous as it brings her heroism to the mundane realm of literally cleaning up the shit that clogs our brains in the form of rhetoric, pride, and the painful never-ending cycle of retaliation. The way she wears the sari pullu, or end, over her head references a Muslim style instead of a Hindu one, thus she stands in solidarity with her Muslim sisters. The goddess is invoked, but not as an icon of Hindu nationalism—which has happened with other Hindu deities, especially Lord Rama. Rather, I hope that she creates an alternative space for empathy, humanity, dialogue, and clarity. She is the energy of transformation amidst tragedy. (S. Moorty, personal communication, January 13, 2012)

In this performance, the goddess for Shyamala is a rhetorical and hermeneutic endeavor that does not draw on an authoritative sacred text or primary revelation. Rather, it is a representation that refuses the identitarian—instead choosing a middle space. In this figure, a feminist ethos is invoked—one that conceives of a sacred deity through the metaphor of “nature,” where nature is understood as all that exists. This figure has a political focus and is used to provide a simultaneously new and old space from which to speak about violence. The eclecticism within this representation helps the audience put into play an alternative notion of religion or spirituality and consequently suggests a different way of thinking about being with an “other.”