Cultural Performance, Acknowledgment, and Social Justice

Violence is not merely killing another. It is violence when we use a sharp word, when we make a gesture to brush away a person, when we obey because there is fear. So violence isn’t merely organized butchery in the name of God, in the name of society or country. Violence is much more subtle, much deeper …

—Jiddu Krishnamurti (1969, 51)

As part of the human condition, innumerable manifestations of violence challenge us during the course of our lives. Around the world, people struggle daily to respond with dignity as they are subjected to terrorist acts, war crimes, racist speeches in public forums, physical and sexual abuse in the home, or deafening silence in response to requests for acknowledgment. Diverse as they are, these forms are undeniably interrelated. As I argued in the initial chapters of this book, hate speech performed in everyday contexts has often made exceptional violence—like religious genocide—appear reasoned or just (Das 2007). At the same time, even the threat of exceptional violence raises apprehension that is real and can constitute a climate of fear in daily life that forecloses the promise of relationality and community.

Sometimes, in our struggle to respond to such problems with dignity and ethical awareness, we make a decision to put ourselves at risk. Perhaps we share our own experiences of violence in public forums and make calls for acknowledgment to an unknown audience. Or maybe we risk ourselves by engaging with another’s experience of violence, with another’s pain. At a certain point, when we are simultaneously confronted by violence and yet free to keep silent, we must ask ourselves difficult questions: Will I speak out publicly? Would I say something that compromises my own well-being if I felt it was true? Could I open my heart and mind in front of potentially hostile audience members? Should I risk my reputation in front of an audience of people with whom I already have relationships—family, friends, and community members—in order to provide or support a critical counternarrative? When community activists answer yes to these questions, they not only answer a call of conscience, they also work toward their own freedom and that of others (Hyde 2006).

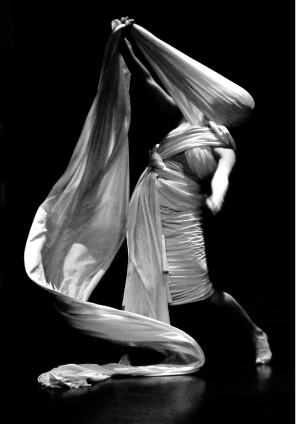

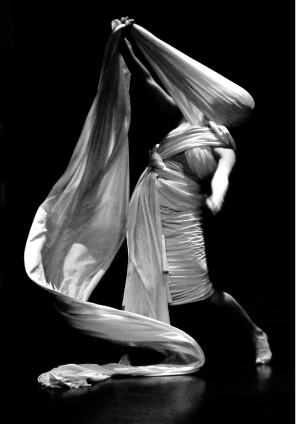

My Silent Cry. Photo credited to Amish Desai.

In this book, I have illustrated the diverse ways in which some contemporary, progressive South Asian American groups endeavor to do just this. Grassroots advocacy groups grounded in the South Asian American community have responded to disparate forms of violence in diverse ways, from political speeches to community forums. This book considers a less conventional, but no less important, means of political activism: community performance. These performances—found within documentaries, progressive community theater, and cultural festivals, among other places—are used to witness transgressions, encourage discussion about contentious issues, and argue for changes in the social environment.

Viewed this way, performances can be understood as “political and ethical means of putting the critical sociological imagination to work” (Denzin and Lincoln 2000, 335). As you have seen, the performances in this book, based on South Asian American women’s personal testimony, play with local, national, and transnational cultural forms as they take up key diasporic concerns, including those of memory and cultural loss, violence and exploitation, social justice, and personal healing. Seen as an intervention and embodied struggle, these performances are meant to broaden consciousness. In doing so, they are not necessarily interested in providing information or answers for audiences, although they sometimes do. Instead, they are more concerned with asking questions or requesting acknowledgment from a desired audience.

These performances are distinctive not only in their cultural form but also in the ways that they critically engage issues of oppression. These activists undertake this risky task despite the personal sacrifice and potential for social censure in order to keep trauma visible, testify to the suffering of others, and engage in the rhetorical work of speaking, listening, and deliberating about important social exigencies facing their communities. This diasporic discourse performs important functions, adding to our social knowledge, shaping interpretations of historic events and periods, and influencing political action among immigrant communities throughout the world.

Consequently, my attention in this book has focused upon the autobiographical and semiautobiographical narratives often embedded within diasporic folk performance as a means of political activism. These performances, found within folk festivals, political blogs, and Web sites, as well as progressive community theater, among others, are used to witness transgressions, encourage discussion about contentious issues, and argue for social change. Many grassroots organizations utilize performances of “narratives of personal experience” or “autobiographical testimonials” to advance calls for acknowledgment. These claims are based in oppositional interpretations of identities, histories, and experiences, both in terms of political and cultural struggles within mainstream society and their struggles for diversity and equality within South Asian American communities and families. This book has sought to explore the contours of these competing struggles as part of broader research being done on testimony, witnessing, social justice, and diasporic rhetoric—focusing on the ways that testimonies can be embedded and intertwined within more artistic cultural performances. Taken together, the performances explored in this book—all of which are performed by women—also open a window into the concerns and aspirations of diasporic South Asians exploring issues of gender and justice through appeals to an ethic of care.

I have suggested that this sense of “care” should be conceptualized as a political concept—as a means of working toward a society in which individuals help one another develop and sustain their basic and innate capabilities, their aesthetic appreciation, their pursuit of knowledge, and their opportunities to associate and organize. We can see this manifestation of care in local and international contexts, from community school involvement to global relief activities to activist performances. In my interest in the critical labor of caring, I find myself particularly aligned with and interested in expanding aspects of Robinson (1999) and Sevenhuijsen’s (1998) work as described in chapter 1. For Robinson, a critical ethic of care is understood as a way of reflecting on morality and moral responsiveness in our communities and in the world at large. In contexts rife with conflict, an ethic of care becomes a way to examine social structures of power within the activities of caring that are taking place. For example, she argues that international relations depend heavily upon citizens caring about potential victims, wanting to prevent their suffering, and understanding what needs to be done.

Held (2006, 18) also puts it well when she argues that this political conception of care goes beyond simply “caring about” a problem experienced by distant others and toward an orientation in which we bring the same attentiveness, responsiveness, and empathy to those distant others that we would to those near to us. Without question, an ethic of care should take the well-being of all humanity into consideration. But “to be concerned for a friend or for a community with which one is closely identified and of which one is a member is to reach out not to someone or something wholly other than oneself but to what shares a part of one’s own self and is implicated in one’s own sense of identity. They are caring relations” (Blum 1980, 42).

I have used this sense of an ethic of care to understand the ways various performance forms enable South Asian Americans to protest violence and request acknowledgment in a manner that invites connection with their fellow citizens and community members. In the process, I have sought to tease out the links between the political performance, diasporic rhetoric, the ethic of care, and acknowledgment. It is through the lens of these theoretical concepts that I believe we can gain new understanding of how some South Asian American women are adding their perspectives to the public sphere and responding to violence directed at them from both outside and inside their communities using artistic means.

Specifically, these performances seem to display the following components:

a. Addressing Problems: Through rhetorical acts of acknowledgment, performers address the problems of others and self in ways that exhibit care. They show audiences how to respond to others’ needs and why they should. Performers point toward how to build trust, mutual concern, and connectedness between people. They encourage people to focus upon their humanity as they make judgments about pressing social matters.

b. Displaying Competency: Acknowledgment in performance requires a rhetorically competent performer—someone whom Hyde (2006) would call a “linguistic architect” whose symbolic constructions “both imagine and invite others into a place where they can feel at home while thinking about and discussing the truth of some matter” (86). To accomplish this task, it is generally considered useful to draw upon familiar topoi or figures, for example. The more people feel at home with another’s arguments and worldviews the more likely they are to open to the other’s viewpoint. In this way, a performance both undertakes an epideictic function and displays a communal character (ethos).

c. Dwelling with Difference: Although rhetorical competence is a key element of acknowledgment, one must also take into consideration what it means to live in a community characterized by deep difference. Within inhospitable dwelling places, individuals with complicated worldviews and identities must strategize with rhetorical competency in order to give a compelling account of themselves, while considering conflicting expectations for “well done” public discourse. In this sense, calls for acknowledgment in performance might appear as a much more open-ended and transgressive act—something not so immediately deducible or intelligible to audience members for the purposes of inviting inquiry.1 Or perhaps, it might be an artistic declaration of personal experience offered by someone who, despite social and cultural taboos, has the courage to speak out and seek acknowledgment of their difference.

2. Creating Caring Communities:

a. Being-For-Others: The act of acknowledgment in performance is a way of “being-for-others.” Within performance contexts, acknowledgment (in discursive and nondiscursive modes) creates a context in which audiences engage in ethical listening (i) to allow performers to tell about the truth of their existence and (ii) to allow audiences to witness the problems of others. At a basic level, this sense of presence is an expression of acknowledgment.

b. Being-With-Others: In performances, rhetorical acts of acknowledgment invoke a sense of communal relationships—a “being-with-others” that shows concern for how people are doing in their everyday relationships with others and in relation to issues of importance. Acts of positive acknowledgment in performance exhibit a profound wakefulness toward others, the challenges they face, and the suffering they have experienced. This acknowledgment involves lingering-with-others.

c. Hospitality-For-Others: Acknowledgment in performance is also a form of hospitality. It is a matter of giving of oneself in order to extend to the audience an invitation to inquire. The aporia of hospitality requires risk in that “to be hospitable is to let oneself be overtaken, surprised, and unprepared” (Derrida 2000, 361). Through acts of acknowledgment, care may appear in the direct interaction that takes place in performances. Here, the feelings of self and Other and connections between people are explored and expressed.

3. Caring for Oneself

a. Performers perform acts for the benefit of others but also for themselves. In this sense, acknowledgment is also a form of self-care. Indeed, sometimes caring for oneself in a performance trumps caring for others; for example, traumatic witnessing of sexual violence may necessitate moments of self-care and reflection, and the seeking of support from the audience.

Given this framework, as I conclude this book, I want to emphasize the need for scholars to focus on the ways local rhetorical practices and vernacular or traditional culture often intertwine. Roger Abrahams’s 1968 article, “Introductory Remarks to a Rhetorical Theory of Folklore,” motivated a generation of folklorists to consider the connections between folklore and rhetoric. These scholars have investigated how folk performances create time and space for deliberations about matters of public and personal importance, raise political consciousness, or constitute identity through critical play with a rich heritage of folk forms, figures, or practices, drawing from philosophers such as Aristotle, Kenneth Burke, or Mikhail Bakhtin (Garlough 2008; Howard 2008; Oring 2008). In this book, I have been interested in building upon this work. Other scholars with human-rights-centered agendas are drawn to exploring the social contexts in which injustice or indifference arise due to conflicts over difference, identity, and sovereignty (Fraser 2000; Markell 2003; Povinelli 2002; Ricoeur 2005). However, given common interests in issues of nationalism, identity politics, ethnic community development, to name only a few, folklore scholars, for the most part, have remained unusually quiet regarding these topics. In addition, calls for acknowledgment in performances by South Asian Americans have gone relatively unnoticed by scholars in fields of communication, such as rhetoric. Perhaps this should come as no surprise, because—despite signs of improvement in recent years—comparatively there has been a dearth of research that addresses non-Western rhetorical performances or those of racial and ethnic minority communities and individuals in the United States (Garlough 2007; Garrett 1997; Hegde 2005; Oliver 1971; Ono and Sloop 2002; Shome 1996; Watts 2002).2

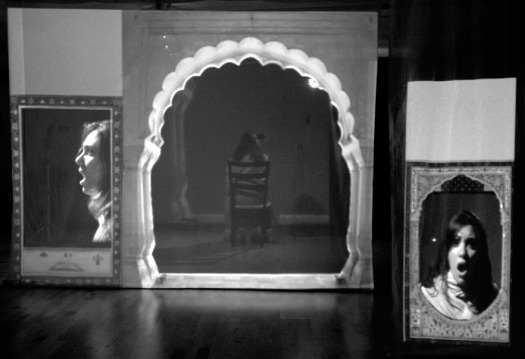

Post Natyam Collective. Photo credited to Andrei Andreev.

To begin, I believe that in order to better research and understand minority, transnational, and global rhetoric, a renewed commitment to interdisciplinary approaches is necessary. Necessary interdisciplinarity goes beyond simply inserting relevant references from related fields. It means engaging in ongoing conversations with experts in other disciplines in order to draw upon their insights and reconfigure them in novel ways to address the questions at hand. Indeed, Elizabeth and Jay Mechling argue that at its core interdisciplinarity has much to do with our ability to play (Mechling and Mechling 1999). It would seem that as a discipline we risk isolation, if not irrelevance, by not recognizing the connections we have and the scholarly contributions we can make, not only to our own field but to those of others as well.

In my own work, I am interested in forging connections with disciplines that deal with culture, particularly folklore. In doing so, I take Thomas B. Farrell’s charge seriously when he argues:

When one is immersed within a cultural “lifeworld,” whether it be that of an urban East Coast street person or that of a Japanese peasant, the rhetorical characteristics of ongoing cultural activities are likely to go unnoticed. This does not mean that they are absent or unimportant, but only that our practices themselves are taken for granted in a way that withholds their partisanship … We are drawn into a more public awareness of rhetoric, when the different activities of others must have an impact upon our needs, priorities, and practices. Rhetoric, in its venerable sense of an art form, emerges when we have recognized features of our activities as directional choices from among an array of options … this means that rhetorical phronesis (practical reason) cannot be enacted without at least a partial intuition of what is appropriate in each historically specific setting. (Farrell 1993, 279)

Certainly, working within this set of assumptions, excellent research has emerged, particularly with regard to the vernacular and popular culture (Brummett 1994; Cloud 2004; Hauser 1999; Ono and Sloop 2002). Yet in the literature that discusses non-Western, ethnic, or immigrant rhetoric, rarely do we see the discipline of folklore engaged. Many are unclear about what folklore is or why it may constitute an important area of inquiry, despite its 150-year history. Perhaps this is because, as the cliché goes, there are as many definitions of folklore as there are folklorists. Folklore is not simply something that is old fashioned or rooted in rural communities. In sometimes unforeseen ways, we throughout our lives participate in vernacular folk culture, whether we live in an isolated farming town or a crowded urban environment.

To be sure, for many decades, there have been folklorists interested in exploring the ways vernacular culture can be used for persuasive purposes, perhaps as potential resources in mobilizing social or political action. However, most are more likely to refer to such communicative forms as strategic or resistive discourse than as rhetoric specifically (Garlough 2008).

For the handful of folklore scholars who have directly engaged with rhetoric, a diverse set of theoretical perspectives has been utilized. Roger Abrahams has focused upon conceptualizing a “rhetorical theory of folklore” that has functionalist undertones but also draws upon Kenneth Burkes’s discussion of symbolic form (Abrahams 1968). Others such as Elliot Oring have applied a neo-Aristotelian approach to reimagine the potential of ethos, pathos, and logos for folklore studies (Oring 2008). My colleague Robert Howard has drawn upon Burke and speech act theory to explore the use of vernacular culture by marginalized groups in online environments (Howard 2008). My own work has tapped into hermeneutic, critical, and performance theory to think through the ways South Asian folklore can be used to invent grassroots political rhetoric (Garlough 2007, 2008). Here, culture is not conceptualized as a set of laws or rules that transform chaos into order, and folklore is not merely a way to construct meaning embedded in public symbols (Burke 1931; Geertz 1973). Instead, folklore is viewed as a way of doing—and the work and play of folklore is rhetorical (Oliver 1971).

Folk forms are considered to be potentially powerful rhetorical forms because they are highly iconic and multidimensional, promote self-reflection and identity formation, create ties to other members of the group, define boundaries, and, ultimately, are readily put to use in defense of an in-group against threats by an out-group. Also, due to their performative quality, these forms can be used to reach out to all members of a community, including individuals who are typically disenfranchised (Kumar 1994). Individuals involved in social organizations and movements can engage in the strategic use of folk forms to confront social issues and to persuade others to ascribe to a particular perspective and act upon it. Many folklore scholars focus attention on the emergence of verbal art in social interaction, rather than the study of a text as a reified object. They have shifted their attention away from issues of classification to those of strategic use (Bauman 1977, 1990, 1992, 1993b). This, I believe, is where rhetoric and folklore has much to say to one another.

Finally, I would like to pause and reflect for a moment upon what I call “critical play”—its characteristics and its potential as a rhetorical concept. Challenging demands to demonstrate total immersion into American culture or exclusive connections to an ethnic community, I have sought to show in this book the ways performers often display a notable cultural and rhetorical competence in critically playing with cultural and institutional discourses and practices in inventive ways that challenge normative thought or practice. For example, in her autobiographical performance titled Rise, Post Natyam performer Shyamala Moorty critically plays with classical Indian Bharatanatyam with ballet and modern dance, along with a toilet plunger, to make visible the ways her diasporic identity puts her at risk for hate crimes immediately following 9/11, while simultaneously drawing parallels to communal violence between Hindus and Muslims in the Indian state of Gujarat. Her work combines a number of the ideas considered in this book—religious divisions, intolerance, and eclectic performances—to challenge norms and preconceptions in inventive ways. Her performance shows the ways that critical play can be conceptualized as an ethical endeavor—one that seeks to facilitate the recovery of a human voice.

In these performances, words and images also work to create the possibility for moments of ethical play between people. Through this play, community identities might be constituted, coalitions might be built, and the limits of community might be explored. Indeed, this play between self and an Other encourages a consideration of the stranger at the borders of the spaces to which we belong. It facilitates reflection upon the ways community can be torn apart by the refusal to acknowledge or recognize others as an integral part of the social fabric. It also shows us the potential connections that can be drawn between everyday folk practices and political performances.

Of course, play is by no means a new concept. In classical Greece, Plato wrote expansively upon the connection between everyday life and play (Krentz 1983). He was one of the first philosophers of rhetoric to observe the importance of play in relationship to the health of the public sphere, civic life, and the creation of a “just city.” In fact, in Plato’s Republic alone, more than sixty citations to play in reference to education can be found (Brandwood 1976). Play, however, is not simply a Western concept. Indeed, Indian classical philosophy is replete with discussions of play (lila), although this play takes place on a more transcendental plane (Hansen 1992; Hatcher 1999).3 Johan Huizinga, the Dutch historian, and one of the founders of modern cultural history also identifies humans as fundamentally playful beings. His work, focusing upon art and spectacle’s role in public life, grew from a background in comparative linguistics and Sanskrit, and culminated in his doctoral thesis on the role of the jester in Indian drama. Later, he extended this understanding in his influential book Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (Huizinga 1950) where he argues that play is the core of every human expression. Indeed, he contended that play is the central component of human culture.

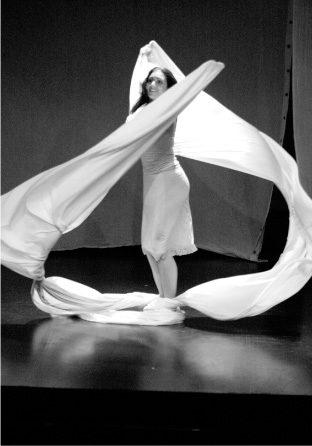

Shyamala Moorty. Photo credited to Michael Burr.

In modern and postmodern scholarship, many scholars have focused upon play as an inventive activity. This sense of invention can be understood in a variety of senses, from the invention of self and culture to rhetorical invention within a text, to the invention that creates space and time for the performance of subjectivity (Conquergood 1989; Sutton-Smith 1997). Victor Turner in From Ritual to Theater: The Human Seriousness of Play (1982) argues that the ludic or play is the essence of invention. Through play with symbols and meanings in performance, ritual, and narrative, individuals can generate multiple alternative models for living, that are able to influence the behavior of those in mainstream social and political roles in the direction of radical change.

For this reason, many folklorists have found play to be a productive concept to consider, as can be seen in the work of Mechling (1980) and Abrahams. For example, in Everyday Life: A Poetics of Vernacular Practice, Abrahams (2005) picks up this thread, asserting that play is a vital dimension of community activity, particularly celebratory gatherings or epideictic events, such as parades, festivals, or commemorative functions with a strong ceremonial component, such as a Fourth of July event. In these events, people assemble to display themselves, often in customary or conventional ways. Abrahams argues that, “from a pragmatic perspective, participants in these shows, displays, and performance events seldom have any problem recognizing and interpreting that something beyond the everyday is taking place” (106). Although these experiences generally rely heavily upon playful mimetic behavior, they also draw considerably upon the vernacular, mimicking it, and then returning participants to the real world. In this vernacular play, participation is key. The greater the involvement, the more potential exists for being carried away by a shared activity. This involves what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990) has called “flow.” Abrahams further contends that, in performance events, this play may consume everyone in its presence, so even if we are not performing ourselves, we are affected sympathetically by body memory or sensations (2005, 110).

Hans Georg Gadamer, building upon the work of Heidegger, also argues that play is such a fundamental function of human life that culture is inconceivable without it. In Truth and Method (1977), Gadamer explores play as a hermeneutical phenomenon of interpretation—the play of understanding. He maintains that, in our lives, understanding is continually in play and, like Freud, notes that this play is characterized by movement. Understanding is endlessly replenished through play—a rhythmic movement in which past meanings influence our everyday lives. This flow surrounds us and we are part of it from the moment of our existence. Each day, in order to create understanding in a chaotic world, our practices, including those that are rhetorical, are invented from our communities’ traditions, histories, norms, and customs. Such hermeneutic rhetorical practice opens us to the imaginary and plays with the always renewable reservoir of memory, history, myth, and desire (Gadamer 2004). Such play extends outward and creates space and time for the potential of dialogue in conversation, literature, speeches, artwork, festivals, ritual practices, and so on. The success of this dialogue relies on the willingness of participants to “give in” to the flow of communication for the “purpose of letting meaning emerge in an ‘event’ of mutual understanding” (Michelfelder and Palmer 1989, 1). Play requires a “playing along” and so even a spectator is more than just an observer. She is one who takes part (Gadamer 1977). In this exchange between self and Other, Gadamer argues that hermeneutics offers a pathway to speaking and listening ethically by finding a common language so that the speaker can be heard by the Other (Watts 2002).

I have found this approach to play helpful in my own thinking about the ways that diasporic individuals and communities negotiate cultural identity and national/transnational belonging. With this in mind, I would like to extend this scholarship to explore play in diasporic performance as a rhetorical concept, especially its critical potential. I wonder, in what ways can we describe critical play as a mode of rhetorical hermeneutics? What comprises its philosophical character, as well as its practical strategies? How can critical play provide conditions for understanding and show where understanding is productively denied? How does it point to where power unfolds?

To begin, I would argue that the concept of critical play calls attention both to questions of power in play and the ways we can play with power. All play is inevitably implicated by power dynamics; in play, there are always rules, no matter where it falls on the continuum between freedom from and duty toward recognized cultural practices (Huizinga 1950). Critical play, more specifically, engages with traditional figures and representations, institutional frameworks, and cultural norms to make a rhetorical point. In the case of this book, the play in these performances is critical and rhetorical because it engages the limits and conditions and consequences of truth-telling. In doing so, it contributes to the formation of subjects. It may help people to reinterpret and appropriate signs of violence, perhaps in gestures of defiance. Through discursive and nondiscursive means, it may voice the pain that has been felt. In doing so, it participates in moral acts of acknowledgment and recognition in ways that evoke an awakening and an unsettling, providing an interruption of discourse and sometimes helps to engender, as Jean-Luc Nancy (2002, 78) says, the “we in us.”

In addition, I believe critical play is intimately related to rhetorical practices of invention, opening the speaker and the audience to the presence of what is expressive and artful. This requires, in most cases, the display of rhetorical competencies. However, it may also necessitate the refusal of this display in rhetorical situations in order to remain committed (in varying degrees) to engagement, speculation, experimentation, and curiosity. In these performances, rhetors may make language and images foreign for audiences to get at what is difficult, puzzling, or distressing and move toward an embodied affective experience. Critical play asks audiences to participate actively—to read into, follow along, imagine, establish independent flights of thought and offer divergent perspectives. They are performances that often foreground the power of the uncanny.

Beyond this, critical play in performance has much to do with kairos—making moments—during which words, images, and bodies interact to create time and space for reflection and deliberation. Critical play is about making the time and space not always available (or welcome) in the public sphere. As the examples in this book illustrate, critical play can take place in a liminal space, at some remove from the mundane in which we live our lives (Turner 1969, 1982; Turner and Schechner 1987). However, I contend that it also can be experienced in the everyday within the vernacular practices. Indeed, in some cases the point of critical play may, in fact, be to challenge the boundaries of the liminal. It contests the power dynamics of social rituals and ceremonies, in order to bring what is supposed to remain in the boundaries into the everyday. In other cases, as we have seen in chapter 2 of this book, critical play makes the flow of time in performance uneven in order to create possibility of understanding.

Drawing upon Gadamer, among others, critical play allows for a way of moving beyond interrogation to a question. In this respect, critical play may do the work of rendering performativity contingent (Doxtader 2011). That is, play is an opening of contingency that blurs the lines between recognizing and acknowledging in contexts of “truth-telling.” In this sense, play embodies the work of discovery. This critical play is related to a hermeneutics that is not necessarily based upon understanding or interpreting. Rather, sometimes it has more to do with simply attending to the Other (Seinlassen) and of letting others come near or creating an opening for questions to emerge. In this way, critical play is a gift—a means of giving and receiving through rhetorical performances.

In sum, in order to understand how this functions in diasporic rhetorical performances, particularly personal experience stories in festivals, documentaries, and progressive theater productions, it seems important to attend to the ways that critical play in diasporic performances may pose important problems of interpretation. This is particularly the case in contexts driven by concern for authenticity, traditional rhetorical competence, and synthesis. In addition, it appears crucial to reflect upon the ways in which critical play within these performances is constrained by cultural translation, appropriateness, and appropriation. Here I am concerned with how and where constitutive power unfolds within performances and how this is achieved through certain rhetorical strategies. Along these lines, I am interested in the ways that such power might function as a form of violence itself.

This framework responds to the longstanding conception of rhetoric as the art of informing, explaining, and entertaining, and reconceives of it as a way of exploring. Performers play through their performances, learning about themselves at the same time as they are connecting with their audiences. The question is what pushes such play to its limits? When does play as meaning making become challenged by the limits of knowing? How can we understand play as a rhetorical means of addressing not-knowing, including not-knowing oneself? How might critical play engage in the ethical? Examining these issues through a series of illustrative cases, this book traces the range and strategies of critical play in diasporic performance. It also further develops the notion of play as an important rhetorical concept, crucial for understanding the political work of marginalized groups.

This book, then, hopes to contribute to the fields of folklore, women’s studies, and rhetoric in numerous ways. It explores how South Asians have responded to the threat and reality of violence, especially since 9/11, during which time a growing number have found themselves the target of prejudice and hate crimes. At the same time, incidents of exclusion, oppression, and abuse remain evident in the South Asian American community, dividing Hindus from Muslims, first generation from second generation, and men from women. As this book documents, South Asian Americans have responded to these challenges by using rhetorical performances to make calls of conscience and invite recognition and acknowledgment from audiences. Emphasizing a politics of difference, the three case studies comprising the core of this book—the development and presentation of a cultural booth at the Minnesota Festival of Nations, the production and content of an eclectic performance drawing attention to hate crimes, and the performance of a feminist spoken-word poetry reading concerning sexual violence within the home—provide a set of portraits of emergent modes of political engagement.

Some employ performance within contexts of conventional engagement, such as large-scale community events like the Minnesota Festival of Nations, events which serve as sites of collective activity and locations of strategic self-presentation. Others emphasize the advocacy work of feminists like the South Asian Sisters. Here, the complexities of a bicultural identity are expressed and demands for tolerance are made through political performances that use everyday culture as a tool for contestation and negotiation. Striving to make the invisible visible, and to foster conversation and deliberation within the South Asian community, these types of performances emanate from the margins of the margins, and offer new ways of understanding the social justice and human rights work of South Asian Americans.

These case studies, then, provide a portrait of contemporary rhetorical practices within the South Asian community, updating a hidden history of immigrant rhetoric in America. This focus on grassroots activism and performance growing out of the borders of a diaspora seeks to trouble essentialized representations of South Asian Americans, redirect attention to intercommunity diversity, and understand the conditions for ethical communication.