12

Frequency-based accounts of

second language acquisition

Nick C. Ellis

Historical discussion

Linguistic background

Language acts as an intermediary between thought and sound in such a way that the combination of both necessarily produces a mutually complementary delimitation of units. Thought, chaotic by nature, is made precise by this process of segmentation. But what happens is neither a transformation of thought into matter, nor a transformation of sound into ideas. What takes place is a somewhat mysterious process by which “thought-sound” evolves divisions, and a language takes place with its linguistic units in between these two amorphous masses.

(Saussure, 1916, pp. 110–111)

Saussure (1916) characterized language as thought organized in sound, and the units of language as linguistic signs, the signifiers of linguistic form and their associated signifieds, the functions, concepts or meanings. In Saussure's view:

(1) Linguistic signs arise from the dynamic interactions of thought and sound—from patterns of usage: “Everything depends on relations .... [1] Words as used in discourse, strung together one after another, enter into relations based on the linear character of languages ... Combinations based on sequentiality may be called syntagmas .... [2] Outside of the context of discourse, words having something [meaningful] in common are associated together in memory. This kind of connection between words is of quite a different order. It is not based on linear sequence. It is a connection in the brain. Such connections are part of that accumulated store which is the form the language takes in an individual's brain. We shall call these associative relations” (pp. 120–121).

(2) Linguistic structure emerges from patterns of usage that are automatically memorized by individual speakers, and these representations and associations collaborate in subsequent language processing: “The whole set of phonetic and conceptual differences which constitute a language are thus the product of two kinds of comparison, associative and syntagmatic. Groups of both kinds are in large part established by the language. This set of habitual relations is what constitutes linguistic structure and determines how the language functions ...” (p. 126). “Any [linguistic] creation must be preceded by an unconscious comparison of the material deposited in the storehouse of language, where productive forms are arranged according to their relations.” (p. 164).

(3) Regular schematic structures are frequency-weighted abstractions across concrete patterns of like-types. “To the language and not to speech, must be attributed all types of syntagmas constructed on regular patterns, ... such types will not exist unless sufficiently numerous examples do indeed occur” (pp. 120–121). “Abstract entities are based ultimately upon concrete entities. No grammatical abstraction is possible unless it has a foundation in the form of some series of material elements, and these are the elements one must come back to finally” (p. 137).

Thus began Structural Linguistics, the study of language as a relational structure, whose elemental constructions derive their forms and functions from their distributions in texts and discourse. This approach had significant impact upon applied linguistics and SLA too. Fries (1952) argued that language acquisition is the learning of an inventory of patterns as arrangements of words with their associated meanings. His (1952) Structure of English presented an analysis of these patterns, Roberts’ (1956) Patterns of English was a textbook presentation of Fries's system for classroom use, and English Pattern Practices, Establishing the Patterns as Habits (Fries et al., 1958) taught beginning and intermediate EFL students English as patterns using audio-lingual drills. Harris (1955, 1968), founder of the first US linguistics department at the University of Pennsylvania, developed rigorous discovery procedures for phonemes and morphemes, based on the distributional properties of these units. For Harris too, form and information (grammar and semantics) were inseparable. He proposed that each human language is a self-organizing system in which both the syntactic and semantic properties of a word are established purely in relation to other words, and that the patterns of a language are learned through exposure to usage in social participation (Harris, 1982, 1991).

Structuralism was the dominant approach in linguistics for the earlier part of the twentieth century. It was overtaken in the 1960s by Generative approaches. Harris's student, Chomsky (1965, 1981) abandoned structure-specific rules and developed the Principles-and-Parameters approach, the general grammatical rules and principles of Universal Grammar. Grammar became top-down and rule-governed, rather than bottom-up and emergent. Structures and functional patterns were no longer interesting for such theories of syntax—instead they were epiphenomena arising from the interaction of more fundamental and universal principles. Chomsky (1981) classified grammatical phenomena into the “core” of the grammar and a “periphery,” where the core phenomena were those describable by the parameterized principles of Universal Grammar, and peripheral phenomena were those marked elements and constructions that are not widespread. Grammar was modularized, encapsulated, and divorced from performance, lexis, social usage, and the rest of cognition. Patterns, structures, constructions, formulaic language, phraseology, all were peripheral. Since Universal Grammar was innate, Linguistics was no longer interested in frequency or learning.

Psychological background

Perception is of definite and probable things.

(James, 1890, p. 82)

From its very beginnings, psychological research has recognized three major experiential factors that affect cognition: frequency, recency, and context (e.g., Anderson, 2010; Bartlett, 1932/ 1967; Ebbinghaus, 1885). Learning, memory and perception are all affected by frequency of usage: the more times we experience something, the stronger our memory of it, and the more fluently it is accessed. The more recently we have experienced something, the stronger our memory of it, and the more fluently it is accessed. The more times we experience conjunctions of features, the more they become associated in our minds and the more these subsequently affect perception and categorization; so a stimulus becomes associated to a context and we become more likely to perceive it in that context. The power law of learning (Anderson, 1982; Ellis and Schmidt, 1998; Newell, 1990) describes the relationships between practice and performance in the acquisition of a wide range of cognitive skills—the greater the practice, the greater the performance, although effects of practice are largest at early stages of learning, thereafter diminishing and eventually reaching asymptote. The power function relating probability of recall (or recall latency) and recency is known as the forgetting curve (Baddeley, 1997; Ebbinghaus, 1885).

William James’ words which begin this section concern the effects of frequency upon perception. There is a lot more to perception than meets the eye, or ear. A percept is a complex state of consciousness in which antecedent sensation is supplemented by consequent ideas which are closely combined to it by association. The cerebral conditions of the perception of things are thus the paths of association irradiating from them. If a certain sensation is strongly associated with the attributes of a certain thing, that thing is almost sure to be perceived when we get that sensation. But where the sensation is associated with more than one reality, unconscious processes weigh the odds, and we perceive the most probable thing: “all brain-processes are such as give rise to what we may call FIGURED consciousness” (James, 1890, p. 82). Accurate and fluent perception thus rests on the perceiver having acquired the appropriately weighted range of associations for each element of the language input.

It is human categorization ability which provides the most persuasive testament to our incessant unconscious figuring or “tallying” (Ellis, 2002a). We know that natural categories are fuzzy rather than monothetic. Wittgenstein's (1953) consideration of the concept game showed that no set of features that we can list covers all the things that we call games, ranging as the exemplars do from soccer, through chess, bridge, and poker, to solitaire. Instead, what organizes these exemplars into the game category is a set of family resemblances among these members—son may be like mother, and mother like sister, but in a very different way. And we learn about these families, like our own, from experience. Exemplars are similar if they have many features in common and few distinctive attributes (features belonging to one but not the other); the more similar are two objects on these quantitative grounds, the faster are people at judging them to be similar (Tversky, 1977). Prototypes, exemplars which are most typical of a category, are those which are similar to many members of that category and not similar to members of other categories. Again, the operationalization of this criterion predicts the speed of human categorization performance—people more quickly classify as birds sparrows (or other average-sized, average-colored, average-beaked, average-featured specimens) than they do birds with less common features or feature combinations like geese or albatrosses (Rosch and Mervis, 1975; Rosch et al., 1976. Prototypes are judged faster and more accurately, even if they themselves have never been seen before—someone who has never seen a sparrow, yet who has experienced the rest of the run of the avian mill, will still be fast and accurate in judging it to be a bird (Posner and Keele, 1970) Such effects make it very clear that although people do not go around consciously counting features, they nevertheless have very accurate knowledge of the underlying frequency distributions and their central tendencies. Cognitive theories of categorization and generalization show how schematic constructions are abstracted over less schematic ones that are inferred inductively by the learner in acquisition (Harnad, 1987; Lakoff, 1987; Taylor, 1998). So Psychology has remained committed to studying these processes of cognition.

Core issues

Although, as we have seen, much of Linguistics post 1960 studiously ignored issues of learning and frequency, the last 50 years of Psycholinguistic research has demonstrated language processing to be exquisitely sensitive to usage frequency at all levels of language representation: phonology and phonotactics, reading, spelling, lexis, morphosyntax, formulaic language, language comprehension, grammaticality, sentence production, and syntax (Ellis, 2002a). Language knowledge involves statistical knowledge, so humans learn more easily and process more fluently high frequency forms and “regular” patterns which are exemplified by many types and which have few competitors. Psycholinguistic perspectives thus hold that language learning is the associative learning of representations that reflect the probabilities of occurrence of form-function mappings. Frequency is a key determinant of acquisition because “rules” of language, at all levels of analysis from phonology, through syntax, to discourse, are structural regularities which emerge from learners’ lifetime analysis of the distributional characteristics of the language input. In James’ terms, learners have to FIGURE language out.

It is these ideas which underpin the last 30 years of investigations of language cognition using connectionist and statistical models (Christiansen and Chater, 2001; Elman et al., 1996; Rumelhart and McClelland, 1986), the competition model of language learning and processing (Bates and MacWhinney, 1987; MacWhinney, 1987b, 1997), the recent re-emergence of interest in how frequency and repetition bring about form in language (Bybee and Hopper, 2001) and how probabilistic knowledge drives language comprehension and production (Bod et al., 2003; Ellis, 2002a, b; Jurafsky and Martin, 2000), and proper empirical investigations of the structure of language by means of corpus analysis (Biber et al., 1999; Sinclair, 1991).

Frequency, learning, and language are now back together, no more so than in Usage-based approaches (Barlow and Kemmer, 2000) which hold that we learn constructions while engaging in communication, the “interpersonal communicative and cognitive processes that everywhere and always shape language” (Slobin, 1997, p. 267). Such beliefs, increasingly influential in the study of child language acquisition, have turned upside-down generative assumptions of innate language acquisition devices, the continuity hypothesis, and top-down, rule-governed, processing, bringing back data-driven, emergent accounts of linguistic systematicities. Constructionist theories of child language acquisition use dense longitudinal corpora to chart the emergence of creative linguistic competence from children's analyses of the utterances in their usage history and from their abstraction of regularities within them (Goldberg, 1995, 2006; Tomasello, 1998, 2003). Children typically begin with phrases and they are initially fairly conservative in extending the use of the particular verb within them to other structures. The usual developmental sequence is from formula to low-scope slot-and-frame pattern to creative construction.1

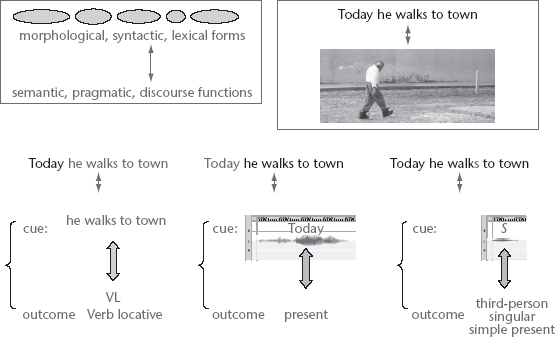

What in the 1950s were known as structural patterns would today also be referred to by other names—“constructions” or “phraseologisms.” Constructions, a term used in Cognitive Linguistic circles, are form-meaning mappings, conventionalized in the speech community, and entrenched as language knowledge in the learner's mind. They are the symbolic units of language relating the defining properties of their morphological, syntactic, and lexical form with particular semantic, pragmatic, and discourse functions (Croft, 2001; Croft and Cruise, 2004; Goldberg, 1995, 2006; Langacker, 1987; Robinson and Ellis, 2008b; Tomasello, 2003). The term phraseologism, more the currency of Corpus Linguistics, adds an additional statistical emphasis to its definition as the co-occurrence of a lexical item and one or more additional linguistic elements which functions as one semantic unit in a clause or sentence and whose frequency of co-occurrence is larger than expected on the basis of chance (Gries, 2008; Howarth, 1998).

Goldberg's (1995, 2003) Construction Grammar argues that all grammatical phenomena can be understood as learned pairings of form (from morphemes, words, idioms, to partially lexically filled and fully general phrasal patterns) and their associated semantic or discourse functions: “the network of constructions captures our grammatical knowledge in toto, i.e., It's constructions all the way down” (Goldberg, 2006, p. 18). There are close relations here with Functional linguistic descriptions of the associations between particular lexico-grammatical patterns and their systemic functions (their propositional, interpersonal, and textual semantics) (Halliday, 1985; Langacker, 1987, 2000). Related developments with a typological perspective, Croft's Radical Construction Grammar (2001; Croft and Cruise, 2004) reject the idea that syntactic categories and relations are universal and argue instead that they are both language- and construction-specific, being induced from particular local frequencies of usage of thought-sound relations. What are universal are the patterns of ways that meanings map onto form.2

What of SLA? Language learners, L1 and L2 both, share the goal of understanding language and how it works. Since they achieve this based upon their experience of language usage, there are many commonalities between first and second language acquisition that can be understood from corpus analyses of input and cognitive- and psycho- linguistic analyses of constructions acquisition following associative and cognitive principles of learning and categorization. Thus usage-based approaches, Cognitive Linguistics and Corpus Linguistics are becoming increasingly influential in SLA research, too (Collins and Ellis, 2009; Ellis, 1998, 2003; Ellis and Cadierno, 2009; Robinson and Ellis, 2008b), albeit with the twist that since L2 learners have previously devoted considerable resources to the estimation of the characteristics of another language—the native tongue in which they have considerable fluency—their computations and inductions are often affected by transfer, with L1-tuned expectations and selective attention (Ellis, 2006b) blinding the acquisition system to aspects of the L2 sample, thus biasing their estimation from naturalistic usage and producing the limited attainment typical of adult L2 acquisition. Thus SLA involves processes of construction and reconstruction.

Data and common elicitation measures

Understanding the mysterious process by which “thought-sound” evolves divisions and a (second) language takes place with its linguistic units in between these two amorphous masses is a hugely interdisciplinary enterprise. As the diverse research cited in this chapter illustrates, it requires the full range of techniques of cognitive science: psycholinguistics, cognitive linguistics, corpus linguistics, connectionism, dynamic systems theory, educational evaluation, child language acquisition, psychology, and computational modeling. Language is a complex adaptive system involving interactions at all levels, and we need to measure these processes and try to understand its emergence thence (Ellis and Larsen-Freeman, 2006b, 2009b; Larsen-Freeman and Cameron, 2008; MacWhinney, 1999). The studies cited in more detail in the next section and elsewhere in this chapter illustrate some of the relevant techniques.

Empirical verification

Figure 12.1 tries to put some illustrative detail to Saussure's thought-sound interface by illustrating a variety of constructions as form-function mappings. If these are the units of language, then language acquisition involves learners infer these associations from their experience of language usage. Psychological analyses of the learning of constructions as form-meaning pairs is informed by the literature on the associative learning of cue-outcome contingencies where the usual determinants include: factors relating to the form such as frequency and salience; factors relating to the interpretation such as significance in the comprehension of the overall utterance, prototypicality, generality, redundancy, and surprise value; factors relating to the contingency of form and function; and factors relating to learner attention, such as automaticity, transfer, overshadowing, and blocking (Ellis, 2002a, 2003, 2006a, 2008c). These various psycholinguistic factors conspire in the acquisition and use of any linguistic construction. Constructionist accounts of language acquisition thus involve the distributional analysis of the language stream and the parallel analysis of contingent perceptual activity, with abstract constructions being learned from the conspiracy of concrete exemplars of usage following statistical learning mechanisms (Christiansen and Chater, 2001) relating input and learner cognition.

The determinants of learning include (1) input frequency (construction frequency, type-token frequency, Zipfian distribution, recency), (2) form (salience and perception), (3) function (prototypicality of meaning, importance of form for message comprehension, redundancy), and (4) interactions between these (contingency of form-function mapping). We will briefly consider each in turn, along with studies demonstrating their applicability:

(1) Input frequency (construction frequency, type-token frequency, Zipfian distribution, recency)

Construction frequency

Frequency of exposure promotes learning. Ellis’ (2002a) review illustrates how frequency effects the processing of phonology and phonotactics, reading, spelling, lexis, morphosyntax, formulaic language, language comprehension, grammaticality, sentence production, and syntax. That language users are sensitive to the input frequencies of these patterns entails that they must have registered their occurrence in processing. These frequency effects are thus compelling evidence for usage-based models of language acquisition which emphasize the role of input.

Type and token frequency

Token frequency counts how often a particular form appears in the input. Type frequency, on the other hand, refers to the number of distinct lexical items that can be substituted in a given slot in a construction, whether it is a word-level construction for inflection or a syntactic construction specifying the relation among words. For example, the “regular” English past tense -ed has a very high type frequency because it applies to thousands of different types of verbs, whereas the vowel change exemplified in swam and rang has much lower type frequency. The productivity of phonological, morphological, and syntactic patterns is a function of type rather than token frequency (Bybee and Hopper, 2001). This is because: (a) the more lexical items that are heard in a certain position in a construction, the less likely it is that the construction is associated with a particular lexical item and the more likely it is that a general category is formed over the items that occur in that position; (b) the more items the category must cover, the more general are its criterial features and the more likely it is to extend to new items; and (c) high type frequency ensures that a construction is used frequently, thus strengthening its representational schema and making it more accessible for further use with new items (Bybee and Thompson, 2000). In contrast, high token frequency promotes the entrenchment or conservation of irregular forms and idioms; the irregular forms only survive because they occur with high frequency. These findings support language's place at the center of cognitive research into human categorization, which also emphasizes the importance of type frequency in classification.

Figure 12.1 Constructions as form-function mappings. Any utterance comprises multiple nested constructions. Some aspects of form are more salient than others—the amount of energy in today far exceeds that in s

Zipfian distribution

In the early stages of learning categories from exemplars, acquisition is optimized by the introduction of an initial, low-variance sample centered upon prototypical exemplars (Elio and Anderson, 1981, 1984). This low variance sample allows learners to get a fix on what will account for most of the category members. The bounds of the category are defined later by experience of the full breadth of exemplar types. Goldberg et al. (2004) demonstrated that in samples of child language acquisition, for a variety of verb-argument constructions (VACs), there is a strong tendency for one single verb to occur with very high frequency in comparison to other verbs used, a profile which closely mirrors that of the mothers’ speech to these children. In natural language, Zipf's law (Zipf, 1935) describes how the highest frequency words account for the most linguistic tokens. Goldberg et al.(2004)show that Zipf's law applies within VACs too, and they argue that this promotes acquisition: tokens of one particular verb account for the lion's share of instances of each particular argument frame; this pathbreaking verb also is the one with the prototypical meaning from which the construction is derived (see also Ninio, 1999, 2006).

Ellis and Ferreira-Junior (2009a, b) investigate effects upon naturalistic second language acquisition of type/token distributions in the islands comprising the linguistic form of English VACs : VL verb locative, VOL verb object locative, VOO ditransitive) in the European Science Foundation corpus (Perdue, 1993). They show that in the naturalistic L2 acquisition of English, VAC verb type/token distribution in the input is Zipfian and learners first acquire the most frequent, prototypical and generic exemplar (e.g., put in VOL, give in VOO, etc.). Their work further illustrates how acquisition is affected by the frequency and frequency distribution of exemplars within each island of the construction (e.g., [Subj V Obj Oblpath/loc]), by their prototypicality, and, using a variety of psychological and corpus linguistic association metrics, by their contingency of form-function mapping. Ellis and Larsen-Freeman (2009a) describe computational (emergent connectionist) serial-recurrent network models of these various factors as they play out in the emergence of constructions as generalized linguistic schema from their frequency distributions in the input.

Recency

Cognitive psychological research shows that three key factors determine the activation of memory schemata: frequency, recency, and context (Anderson, 1989; Anderson and Schooler, 2000). Language processing also reflects recency effects (Segalowitz and Trofimovich, Chapter 11, this volume). This phenomenon is known as priming and may be observed in phonology, conceptual representations, lexical choice, and syntax (McDonough and Trofimovich, 2008). Syntactic priming refers to the phenomenon of using a particular syntactic structure given prior exposure to the same structure. This behavior has been observed when speakers hear, speak, read, or write sentences (Bock, 1986; Pickering, 2006; Pickering and Garrod, 2006). For SLA, Gries and Wulff (2005) showed (i) that advanced L2 learners of English showed syntactic priming for ditransitive (e.g., The racing driver showed the helpful mechanic) and prepositional dative (e.g., The racing driver showed the torn overall ...) argument structure constructions in a sentence completion task, (ii) that their semantic knowledge of argument structure constructions affected their grouping of sentences in a sorting task, and (iii) that their priming effects closely resembled those of native speakers of English in that they were very highly correlated with native speakers’ verbal subcategorization preferences whilst completely uncorrelated with the subcategorization preferences of the German translation equivalents of these verbs. There is now a growing body of research demonstrating such L2 syntactic priming effects (McDonough and Mackey, 2006; McDonough, 2006)

(2) Form (salience and perception)

The general perceived strength of stimuli is commonly referred to as their salience. Low salience cues tend to be less readily learned. Ellis (2006a, b) summarized the associative learning research demonstrating that selective attention, salience, expectation, and surprise are key elements in the analysis of all learning, animal and human alike. As the Rescorla-Wagner (1972) model encapsulates, the amount of learning induced from an experience of a cue-outcome association depends crucially upon the salience of the cue and the importance of the outcome.

Many grammatical meaning-form relationships, particularly those that are notoriously difficult for second language learners like grammatical particles and inflections such as the third-person singular –s of English, are of low salience in the language stream. For example, some forms are more salient: “today” is a stronger psychophysical form in the input than is the morpheme “-s” marking third-person singular present tense, thus while both provide cues to present time, today is much more likely to be perceived, and -s can thus become overshadowed and blocked, making it difficult for second language learners of English to acquire (Ellis, 2006b, 2008a; Goldschneider and DeKeyser, 2001).

(3) Function (prototypicality of meaning, importance of form for message comprehension, redundancy)

Prototypicality of meaning

Categories have graded structure, with some members being better exemplars than others. In the prototype theory of concepts (Rosch and Mervis, 1975; Rosch et al., 1976), the prototype as an idealized central description is the best example of the category, appropriately summarizing the most representative attributes of a category. As the typical instance of a category, it serves as the benchmark against which surrounding, less representative instances are classified. The greater the token frequency of an exemplar, the more it contributes to defining the category, and the greater the likelihood it will be considered the prototype. The best way to teach a concept is to show an example of it. So the best way to introduce a category is to show a prototypical example.

Ellis and Ferreira-Junior (2009a) show that the verbs that second language learners first used in particular VACs are prototypical and generic in function (go for VL, put for VOL, and give for VOO). The same has been shown for child language acquisition, where a small group of semantically general verbs, often referred to as light verbs (e.g., go, do, make, come) are learned early (Clark, 1978; Ninio, 1999; Pinker, 1989). Ninio argues that, because most of their semantics consist of some schematic notion of transitivity with the addition of a minimum specific element, such verbs are semantically suitable, salient, and frequent; hence, learners start transitive word combinations with these generic verbs. Thereafter, as Clark describes, “many uses of these verbs are replaced, as children get older, by more specific terms .... General purpose verbs, of course, continue to be used but become proportionately less frequent as children acquire more words for specific categories of actions” (p. 53).

Redundancy

The Rescorla-Wagner model (1972) also summarizes how redundant cues tend not to be acquired. Not only are many grammatical meaning-form relationships low in salience, but they can also be redundant in the understanding of the meaning of an utterance. For example, it is often unnecessary to interpret inflections marking grammatical meanings such as tense because they are usually accompanied by adverbs that indicate the temporal reference. Second language learners’ reliance upon adverbial over inflectional cues to tense has been extensively documented in longitudinal studies of naturalistic acquisition (Bardovi-Harlig, 2000; Dietrich et al., 1995), training experiments (Ellis, 2007; Ellis and Sagarra, 2010), and studies of L2 language processing (VanPatten, 2006).

(4) Interactions between these (contingency of form-function mapping)

Psychological research into associative learning has long recognized that while frequency of form is important, so too is contingency of mapping (Shanks, 1995). Consider how, in the learning of the category of birds, while eyes and wings are equally frequently experienced features in the exemplars, it is wings which are distinctive in differentiating birds from other animals. Wings are important features to learning the category of birds because they are reliably associated with class membership, eyes are not. Raw frequency of occurrence is less important than the contingency between cue and interpretation. Distinctiveness or reliability of form-function mapping is a driving force of all associative learning, to the degree that the field of its study has been known as “contingency learning” since Rescorla (1968) showed that for classical conditioning, if one removed the contingency between the conditioned stimulus (CS) and the unconditioned (US), preserving the temporal pairing between CS and US but adding additional trials where the US appeared on its own, then animals did not develop a conditioned response to the CS. This result was a milestone in the development of learning theory because it implied that it was contingency, not temporal pairing, that generated conditioned responding. Contingency, and its associated aspects of predictive value, information gain, and statistical association, have been at the core of learning theory ever since. It is central in psycholinguistic theories of language acquisition, too (Ellis, 2006a, b, 2008c; Gries and Wulff, 2005; MacWhinney, 1987b), with the most developed account for second language acquisition being that of the Competition model (MacWhinney, 1987a, 1997, 2001). Ellis and Ferreira-Junior (2009b) use Delta P (ΔP) and collostructional analysis measures (Gries and Stefanowitsch, 2004; Stefanowitsch and Gries, 2003) to investigate effects of form-function contingency upon L2 VAC acquisition. Wulff et al. (2009) use multiple distinctive collexeme analyses to investigate effects of reliability of form-function mapping in the second language acquisition of tense and aspect. Boyd and Goldberg (2009) use conditional probabilities to investigate contingency effects in VAC acquisition. This is still an active area of inquiry, and more research is required before we know which statistical measures of form-function contingency are more predictive of acquisition and processing.

There is thus a range of frequency-related factors that influence the acquisition of linguistic constructions. For the example of verb-argument constructions illustrated to the left of Figure 12.1, there is:

(1) the frequency, the frequency distribution, and the salience of the form types,

(2) the frequency, the frequency distribution, the prototypicality and generality of the semantic types, and their importance in interpreting the overall construction,

(3) the reliabilities of the mapping between 1 and 2, and,

(4) the degree to which the different elements in the VAC sequence (such as Subj V Obj Obl) are mutually informative and form predictable chunks.

There are many factors involved, and research to date has tended to look at each hypothesis, variable by variable, one at a time. But they interact. And what we really want is a model of usage and its effects upon acquisition. We can measure these factors individually. But such counts are vague indicators of how the demands of human interaction affect the content and ongoing co-adaptation of discourse, how this is perceived and interpreted, how usage episodes are assimilated into the learner's system, and how the system reacts accordingly. We need a model of learning, development, and emergence that takes these factors into account dynamically. I will return to this prospect in the final section of this chapter.

Applications

Language learners have to acquire the constructions of their language from usage. Learning is dynamic, it takes place during processing, as Hebb (1949), Craik and Lockhart (1972), Elman et al. (1996) and Bybee and Hopper (2001) have variously emphasized from their neural, cognitive, connectionist, and linguistic perspectives, and the units of learning are thus the units of language processing episodes. Before learners can use constructions productively, they have to encounter useful exemplars and analyze them to identify their linguistic form, their meaning, and the mapping between these. Since every stimulus is ambiguous, forms, meanings, and their mappings have to be tallied—probabilistic statistical information is an inherent part of the representation of every construction. The tallying that provides this information takes place implicitly during processing. Implicit learning supplies a distributional analysis of the problem space: Frequency of usage determines availability of representation according to the power law of learning, and this process tallies the likelihoods of occurrence of constructions and the relative probabilities of their mappings between aspects of form and interpretations, with generalizations arising from conspiracies of memorized utterances collaborating in productive schematic linguistic constructions. Every language comprises very many constructions. It is no wonder then that the accomplishment of native levels of attainment involve thousands of hours on the task of language usage. There is no substitute for this. Learners’ cognitive systems have to be allowed sufficient exposure to allow Saussure's somewhat mysterious process by which “thought-sound” evolves divisions, and language to take place with its linguistic units in between these two amorphous masses.

A language is not a fixed system. It varies in usage over speakers, places, and time. Yet despite the fact that no two speakers own an identical language, communication is possible to the degree that they share constructions (form-meaning correspondences) relevant to their discourse. Learners have to enter into communication from experience of a very limited number of tokens. Their limited exposure poses them the task of estimating how linguistic constructions work from an input sample that is incomplete, uncertain, and noisy. Native-like fluency, idiomaticity, and selection are another level of difficulty again. For a good fit, every utterance has to be chosen, from a wide range of possible expressions, to be appropriate for that idea, for that speaker, for that place, and for that time. And again, learners can only estimate this from their finite experience.

Language, a moving target then, can neither be described nor experienced comprehensively, and so, in essence, language learning is estimation from sample. Like other estimation problems, successful determination of the population characteristics is a matter of statistical sampling, description, and inference. For language learning the estimations include: What is the range of constructions in the language? What are their major types? Which are the really useful ones? What is their relative frequency distribution? How do they map function and form, and how reliably so? How can this information best be organized to allow its appropriate and fluent access in recognition and production? Are there variable ways of expressing similar meanings? How are they distributed across different contexts? And so on.

There are three fundamental instructional aspects of this conception of language learning as statistical sampling and estimation.

(1) The first and foremost concerns sample size: As in all surveys, the bigger the sample, the more accurate the estimates, but also the greater the costs. Native speakers estimate their language over a lifespan of usage. L2 and foreign language (FL) learners just don't have that much time or resource. Thus, they are faced with a task of optimizing their estimates of language from a limited sample of exposure. Broadly, power analysis dictates that attaining native-like fluency and idiomaticity requires much larger usage samples than does basic interpersonal communicative competence in predictable contexts. But for the particulars, the instructor must ask what sort of sample is needed to adequately assess the workings of constructions of, respectively, high, medium, and low base occurrence rates, of more categorical versus more fuzzy patterns, of regular vs. irregular systems, of simple vs. complex “rules,” of dense versus sparse neighborhoods?

Corpus and Cognitive Linguistic analyses are essential to the determination of which constructions of differing degrees of schematicity are worthy of instruction, their relative frequency, and their best (= central and most frequent) examples for instruction and assessment (Biber et al., 1998; 1999). Gries (2007) describes how the three basic methods of corpus linguistics (frequency lists, concordances, and collocations) inform the instruction of L2 constructions. Achard (2008), Tyler (2008), Robinson and Ellis (2008a) and other readings in Robinson and Ellis (2008b) show how an understanding of the item-based nature of construction learning inspires the creation and evaluation of instructional tasks, materials, and syllabi, and how cognitive linguistic analyses can be used to inform learners how constructions are conventionalized ways of matching certain expressions to specific situations and to guide instructors in precisely isolating and clearly presenting the various conditions that motivate speaker choice.

(2) The second concerns sample selection: Principles of survey design dictate that a sample must properly represent the strata of the population of greatest concern. Thus, Needs Analysis is relevant to all L2 learners. Thus, too, the truism that FL learners, who have much more limited access to the authentic natural source language than L2 learners, are going to have greater problems of adequate description. But what about learning particular constructions? What is the best sample of experience to support this? How many examples do we need? In what proportion of types and tokens? Are there better sequences of experience to optimize estimation? I will briefly consider the identification of the patterns to teach, and then suggestions for ordering exemplars to optimize schematic construction learning.

Corpus linguistics, genre analysis, and needs analysis have a large role to play in identifying the linguistic constructions of most relevance to particular learners. For example, every genre of English for Academic Purposes and English for Special Purposes has its own phraseology, and learning to be effective in the genre involves learning this (Swales, 1990). Lexicographers develop their learner dictionaries upon relevant corpora (Hunston and Francis, 1996; Ooi, 1998) and dictionaries focus upon examples of usage as much as definitions, or even more so. Good grammars are now frequency informed (Biber et al., 1999). Corpus linguistic analysis techniques have been used to identify the words relevant to academic English (the Academic Word List, Coxhead, 2000) and this, together with knowledge of lexical acquisition and cognition, informs vocabulary instruction programs (Nation, 2001; Schmitt, 2000). Similarly, corpus techniques have been used to identify formulaic phrases that are of special relevance to academic discourse and to inform their instruction (the Academic Formulas List, Ellis et al., 2008; Simpson-Vlach and Ellis, in preparation).

Cognitive linguistics and psycholinguistics have a role to play in informing the ordering of exemplars for optimal acquisition of a schematic construction. Current work in cognitive linguistics and child language acquisition (e.g., Bybee, 2008; Goldberg, 2008; Lieven and Tomasello, 2008) suggests that for the initial acquisition of a productive schematic construction, optimal acquisition should occur when the central members of the category are presented early and often. This initial, low-variance sample centered upon prototypical exemplars should allow learners to get a “fix” on the central tendency that will account for most of the category members. Tokens that are more frequent have stronger representations in memory and serve as the analogical basis for forming novel instances of the category. Then more diverse exemplars should be introduced in order for learners to be able to determine the full range and bounds of the category. It is type frequency which drives productivity of pattern. It seems that Zipfian distributions in the constructions of natural language naturally provide learners with such samples in natural language. As a general instructional heuristic then, this is probably a good rule-of-thumb, although further work is needed to determine its applicability in L2 acquisition to the full range of constructions, and to particular learners and their L1s (Collins and Ellis, 2009; Ellis and Cadierno, 2009).

(3) A final implication of language acquisition as estimation concerns sampling history: How does knowledge of some cues and constructions affect estimation of the function of others? What is the best sequence of language to promote learning new constructions? And what is the best processing orientation to make this sample of language the appropriate sample of usage?

Cognitive Linguistics is the analysis of these mechanisms and processes that underpin what Slobin (1996) called “thinking for speaking.” But learning an L2 requires “rethinking for speaking.” In order to counteract the L1 biases to allow estimation procedures to optimize induction, all of the L2 input needs to be made to count (as it does in L1 acquisition), not just the restricted sample typical of the biased intake of L2 acquisition. Reviews of the experimental and quasi-experimental investigations into the effectiveness of L2 instruction (e.g., Doughty and Williams, 1998; Ellis and Laporte, 1997; Hulstijn and DeKeyser, 1997; Lightbown et al., 1993; Long, 1983; Spada, 1997), particularly the comprehensive meta-analysis of Norris and Ortega (2000), demonstrate that focused L2 instruction results in substantial target-oriented gains, that explicit types of instruction are more effective than implicit types, and that the effectiveness of L2 instruction is durable. Form-focused instruction can help to achieve this by recruiting learners’ explicit, conscious processing to allow them to consolidate unitized form-function bindings of novel L2 constructions (Ellis, 2005). Once a construction has been represented in this way, so its use in subsequent processing can update the statistical tallying of its frequency of usage and probabilities of form-function mapping.

Future directions

The intuitions of Ferdinand de Saussure and William James were basically correct—we can count on that. Saussure (1916) said, “To speak of a ‘linguistic law’ in general is like trying to lay hands on a ghost ... Synchronic laws are general, but not imperative ... [they] are imposed upon speakers by the constraints of common usage ... In short, when one speaks of a synchronic law, one is speaking of an arrangement, or a principle of regularity” (pp. 90–91). The frequencies of common usage count in the emergence of regularity in SLA. Usage is rich in latent linguistic structure.

Nevertheless, as Einstein observed, “Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; everything that counts cannot necessarily be counted.” Corpus Linguistics provides the proper empirical means whereby everything in language texts can be counted. But counts on the page are not the same as counts in the head. Cognitive Linguistics, mindful of research on categorization, recognizes frequency as a force in linguistic representation, processing, and change, and psycholinguistic demonstrations of language users’ sensitivity to the frequencies of occurrence of a wide range of different linguistic constructions suggests an influence of usage events upon the user's system. But not everything that we can count in language counts in language cognition and acquisition.

The study of SLA from corpus linguistic and cognitive linguistic perspectives is a two-limbed stool without triangulation from an understanding of the psychology of cognition, learning, attention, and development. Sensation is not perception, and the psychophysical relations mapping physical onto psychological scales are complex. The world of conscious experience is not the world itself but a perception crucially determined by attentional limitations, prior knowledge, and context. Not every experience is equal—effects of practice are greatest at early stages but eventually reach asymptote. The associative learning of constructions as form-meaning pairs is affected by: factors relating to the form such as frequency and salience; factors relating to the interpretation such as significance in the comprehension of the overall utterance, prototypicality, generality, redundancy, and surprise value; factors relating to the contingency of form and function; and factors relating to learner attention, such as automaticity, transfer, and blocking.

Even a three-limbed stool does not make much sense without an appreciation of its social use. The connectionist networks that compute these associations are embodied, attentionally and socially gated, conscious, dialogic, interactive, situated, and cultured (Ellis, 2008b). Language usage, social roles, language learning, and conscious experience are all socially situated, negotiated, scaffolded, and guided. They emerge in the play of social intercourse. All these factors conspire dynamically in the acquisition and use of any linguistic construction. The future lies in trying to understand the component dynamic interactions at all levels, and the consequent emergence of the complex adaptive system of language itself (Ellis and Larsen-Freeman, 2006a, 2009b).

Notes

1 Remember Saussure's “abstract entities are based ultimately upon concrete entities. No grammatical abstraction is possible unless it has a foundation in the form of some series of material elements, and these are the elements one must come back to finally.”

2 Remember Saussure's “somewhat mysterious process by which ‘thought-sound’ evolves divisions, and a language takes place with its linguistic units in between these two amorphous masses.”

References

Achard, M. (2008). Cognitive pedagogical grammar. In P. Robinson and N. C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition. London: Routledge.

Anderson, J. R. (1982). Acquisition of cognitive skill. Psychological Review, 89(4), 369–406.

Anderson, J. R. (1989). A rational analysis of human memory. In H. L. I. Roediger and F. I. M. Craik (Eds.), Varieties of memory and consciousness: Essays in honour of Endel Tulving (pp. 195–210). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Anderson, J. R. (2010). Cognitive psychology and its implications (Seventh Edition). New York: Worth Publishers.

Anderson, J. R. and Schooler, L. J. (2000). The adaptive nature of memory. In E. Tulving and F. I. M. Craik (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of memory (pp. 557–570). London: Oxford University Press.

Baddeley, A. D. (1997). Human memory: Theory and practice Revised Edition. Hove: Psychology Press.

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2000). Tense and aspect in second language acquisition: Form, meaning, and use. Oxford: Blackwell.

Barlow, M., and Kemmer, S. (Eds.). (2000). Usage based models of language. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Bartlett, F. C. ([1932] 1967). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bates, E. and MacWhinney, B. (1987). Competition, variation, and language learning. In B. MacWhinney (Ed.), Mechanisms of language acquisition (pp. 157–193). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Biber, D., Conrad, S., and Reppen, R. (1998). Corpus linguistics: Investigating language structure and use. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., and Finegan, E. (1999). Longman grammar of spoken and written English. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education.

Bock, J. K. (1986). Syntactic persistence in language production. Cognitive Psychology, 18, 355–387.

Bod, R., Hay, J., and Jannedy, S. (Eds.) (2003). Probabilistic linguistics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Boyd, J. K. and Goldberg, A. E. (2009). Input effects within a constructionist framework. The Modern Language Journal, 93(2), 418–429.

Bybee, J. (2008). Usage-based grammar and second language acquisition. In P. Robinson and N. C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition. London: Routledge.

Bybee, J. and Hopper, P. (Eds.) (2001). Frequency and the emergence of linguistic structure. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bybee, J. and Thompson, S. (2000). Three frequency effects in syntax. Berkeley Linguistic Society, 23, 65–85.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Christiansen, M. H. and Chater, N. (Eds.). (2001). Connectionist psycholinguistics. Westport, CO: Ablex.

Clark, E. V. (1978). Discovering what words can do. In D. Farkas, W. M. Jacobsen, and K. W. Todrys (Eds.), Papers from the parasession on the lexicon, Chicago Linguistics Society April 14–15, 1978 (pp. 34–57). Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society.

Collins, L. and Ellis, N. C. (2009). Input and second language construction learning: Frequency, form, and function. The Modern Language Journal, 93(2), Whole issue.

Coxhead, A. (2000). A new Academic Word List. TESOL Quarterly, 34, 213–238.

Craik, F. I. M. and Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11, 671–684.

Croft, W. (2001). Radical construction grammar: Syntactic theory in typological perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Croft, W. and Cruise, A. (2004). Cognitive linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dietrich, R., Klein, W., and Noyau, C. (Eds.) (1995). The acquisition of temporality in a second language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Doughty, C. and Williams, J. (Eds.) (1998). Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology (H. A. R. C. E. B. (1913), Trans.). New York: Teachers College, Columbia.

Elio, R. and Anderson, J. R. (1981). The effects of category generalizations and instance similarity on schema abstraction. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 7(6), 397–417.

Elio, R. and Anderson, J. R. (1984). The effects of information order and learning mode on schema abstraction. Memory and Cognition, 12(1), 20–30.

Ellis, N. C. (1998). Emergentism, connectionism and language learning. Language Learning, 48(4), 631–664.

Ellis, N. C. (2002a). Frequency effects in language processing: A review with implications for theories of implicit and explicit language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24(2), 143–188.

Ellis, N. C. (2002b). Reflections on frequency effects in language processing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24(2), 297–339.

Ellis, N. C. (2003). Constructions, chunking, and connectionism: The emergence of second language structure. In C. Doughty and M. H. Long (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ellis, N. C. (2005). At the interface: Dynamic interactions of explicit and implicit language knowledge. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27, 305–352.

Ellis, N. C. (2006a). Language acquisition as rational contingency learning. Applied Linguistics, 27(1), 1–24.

Ellis, N. C. (2006b). Selective attention and transfer phenomena in SLA: Contingency, cue competition, salience, interference, overshadowing, blocking, and perceptual learning. Applied Linguistics, 27(2), 1–31.

Ellis, N. C. (2007). Blocking and learned attention in language acquisition. CogSci 2007, Proceedings of the twenty ninth cognitive science conference. Nashville, Tennesse, August 1–4.

Ellis, N. C. (2008a). The dynamics of language use, language change, and first and second language acquisition. The Modern Language Journal, 41(3), 232–249.

Ellis, N. C. (2008b). The psycholinguistics of the interaction hypothesis. In A. Mackey and C. Polio (Eds.), Multiple perspectives on interaction in SLA: Second language research in honor of Susan M. Gass (pp. 11–40). New York: Routledge.

Ellis, N. C. (2008c). Usage-based and form-focused language acquisition: The associative learning of constructions, learned-attention, and the limited L2 endstate. In P. Robinson and N. C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition. London: Routledge.

Ellis, N. C. and Cadierno, T. (2009). Constructing a second language. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 7(Special section), 111–290.

Ellis, N. C. and Ferreira-Junior, F. (2009a). Construction learning as a function of frequency, frequency distribution, and function. The Modern Language Journal, 93, 370–386.

Ellis, N. C. and Ferreira-Junior, F. (2009b). Constructions and their acquisition: Islands and the distinctiveness of their occupancy. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 7, 188–221.

Ellis, N. C. and Laporte, N. (1997). Contexts of acquisition: Effects of formal instruction and naturalistic exposure on second language acquisition. In A. M. DeGroot and J. F. Kroll (Eds.), Tutorials in bilingualism: Psycholinguistic perspectives (pp. 53–83). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ellis, N. C. and Larsen Freeman, D. (2006a). Language emergence: Implications for Applied Linguistics. Applied Linguistics, 27(4), whole issue.

Ellis, N. C. and Larsen Freeman, D. (2006b). Language emergence: Implications for applied linguistics (introduction to the special issue). Applied Linguistics, 27(4), 558–589.

Ellis, N. C. and Larsen-Freeman, D. (2009a). Constructing a second language: Analyses and computational simulations of the emergence of linguistic constructions from usage. Language Learning, 59 (Supplement 1), 93–128.

Ellis, N. C. and Larsen-Freeman, D. (2009b). Language as a complex adaptive system [Special issue]. Language Learning, 59 (Supplement 1).

Ellis, N. C. and Sagarra, N. (2010). The bounds of adult language acquisition: Blocking and learned attention. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 32(4), 553–580.

Ellis, N. C. and Schmidt, R. (1998). Rules or associations in the acquisition of morphology? The frequency by regularity interaction in human and PDP learning of morphosyntax. Language and Cognitive Processes, 13(2and3), 307–336.

Ellis, N. C., Simpson-Vlach, R., and Maynard, C. (2008). Formulaic language in native and second-language speakers: Psycholinguistics, corpus linguistics, and TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 42(3), 375–396.

Elman, J. L., Bates, E. A., Johnson, M. H., Karmiloff-Smith, A., Parisi, D., and Plunkett, K. (1996). Rethinking innateness: A connectionist perspective on development. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fries, C. C. (1952). The structure of English. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

Fries, C. C. and Lado, R. and the Staff of the Michigan English Language Institute (1958). English pattern practices: Establishing the patterns as habits. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Goldberg, A. E. (1995). Constructions: A construction grammar approach to argument structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Goldberg, A. E. (2003). Constructions: A new theoretical approach to language. Trends in Cognitive Science, 7, 219–224.

Goldberg, A. E. (2006). Constructions at work: The nature of generalization in language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goldberg, A. E. (2008). The language of constructions. In P. Robinson and N. C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition. London: Routledge.

Goldberg, A. E., Casenhiser, D. M., and Sethuraman, N. (2004). Learning argument structure generalizations. Cognitive Linguistics, 15, 289–316.

Goldschneider, J. M. and DeKeyser, R. (2001). Explaining the “natural order of L2 morpheme acquisition” in English: A meta-analysis of multiple determinants. Language Learning, 51, 1–50.

Gries, S. T. (2007). Corpus-based methods in analyses of SLA data. In P. Robinson and N. C. Ellis (Eds.), A handbook of cognitive linguistics and SLA. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gries, S. T. (2008). Phraseology and linguistic theory: A brief survey. In S. Granger and F. Meunier (Eds.), Phraseology: An interdisciplinary perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Gries, S. T. and Stefanowitsch, A. (2004). Extending collostructional analysis: A corpus-based perspective on “alternations”. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 9, 97–129.

Gries, S. T. and Wulff, S. (2005). Do foreign language learners also have constructions? Evidence from priming, sorting, and corpora. Annual Review of Cognitive Linguistics, 3, 182–200.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1985). An introduction to functional grammar. London: E. Arnold.

Harnad,S.(Ed.).(1987). Categorical perception: The groundwork of cognition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Harris, Z. (1955). From phoneme to morpheme. Language, 31, 190–222.

Harris, Z. (1968). Mathematical structures of language. New York: Wiley and Sons.

Harris, Z. (1982). A grammar of English on mathematical principles. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Harris, Z. (1991). A theory of language and information: A mathematical approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hebb, D. O. (1949). The organization of behaviour. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Howarth, P. (1998). Phraseology and second language proficiency. Applied Linguistics, 19(1), 24–44.

Hulstijn, J. and DeKeyser, R. (Eds.) (1997). Testing SLA theory in the research laboratory. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19, 2 [Special issue].

Hunston, S. and Francis, G. (1996). Pattern grammar: A corpus driven approach to the lexical grammar of English. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology (Vol. 1). New York: Holt.

Jurafsky, D. and Martin, J. H. (2000). Speech and language processing: An introduction to natural language processing, speech recognition, and computational linguistics. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Langacker, R. W. (1987). Foundations of cognitive grammar: Vol. 1. Theoretical prerequisites. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Langacker, R. W. (2000). A dynamic usage-based model. In M. Barlow and S. Kemmer (Eds.), Usage-based models of language (pp. 1–63). Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Larsen-Freeman, D. and Cameron, L. (2008). Complex systems and applied linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lieven, E. and Tomasello, M. (2008). Children's first language acquisition from a usage-based perspective. In P. Robinson and N. C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition. New York and London: Routledge.

Lightbown, P. M., Spada, N., and White, L. (1993). The role of instruction in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 15 [Special issue].

Long, M. H. (1983). Does second language instruction make a difference? A review of research. TESOL Quarterly, 17, 359–382.

MacWhinney, B. (1987a). Applying the Competition Model to bilingualism. Applied Psycholinguistics, 8(4), 315–327.

MacWhinney, B. (1987b). The Competition Model. In B. MacWhinney (Ed.), Mechanisms of language acquisition (pp. 249–308). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

MacWhinney, B. (1997). Second language acquisition and the Competition Model. In A. M. B. De Groot and J. F. Kroll (Eds.), Tutorials in bilingualism: Psycholinguistic perspectives (pp. 113–142). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

MacWhinney, B. (Ed.) (1999). The emergence of language. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

MacWhinney, B. (2001). The competition model: The input, the context, and the brain. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 69–90). New York: Cambridge University Press.

McDonough, K. (2006). Interaction and syntactic priming: English L2 speakers’ production of dative constructions. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28, 179–207.

McDonough, K. and Mackey, A. (2006). Responses to recasts: Repetitions, primed production and linguistic development. Language Learning, 56, 693–720.

McDonough, K. and Trofimovich, P. (2008). Using priming methods in second language research. London: Routledge.

Nation, P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Newell, A. (1990). Unified theories of cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ninio, A. (1999). Pathbreaking verbs in syntactic development and the question of prototypical transitivity. Journal of Child Language, 26, 619–653.

Ninio, A. (2006). Language and the learning curve: A new theory of syntactic development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norris, J. and Ortega, L. (2000). Effectiveness of L2 instruction: A research synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis. Language Learning, 50, 417–528.

Ooi, V. B. Y. (1998). Computer corpus lexicography. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Perdue, C. (Ed.) (1993). Adult language acquisition: Crosslinguistic perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pickering, M. J. (2006). The dance of dialogue. The Psychologist, 19, 734–737.

Pickering, M. J. and Garrod, S. C. (2006). Alignment as the basis for successful communication. Research on Language and Computation, 4, 203–228.

Pinker, S. (1989). Learnability and cognition: The acquisition of argument structure. Cambridge, MA: Bradford Books.

Posner, M. I. and Keele, S. W. (1970). Retention of abstract ideas. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 83, 304–308.

Rescorla, R. A. (1968). Probability of shock in the presence and absence of CS in fear conditioning. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 66, 1–5.

Rescorla, R. A. and Wagner, A. R. (1972). A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. In A. H. Black and W. F. Prokasy (Eds.), Classical conditioning II: Current theory and research (pp. 64–99). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Roberts, P. (1956). Patterns of English. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World.

Robinson, P. and Ellis, N. C. (2008a). Conclusion: Cognitive linguistics, Second language acquisition and L2 instruction—issues for research. In P. Robinson and N. C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition. London: Routledge.

Robinson, P. and Ellis, N. C. (Eds.) (2008b). A handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition. London: Routledge.

Rosch, E. and Mervis, C. B. (1975). Cognitive representations of semantic categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104, 192–233.

Rosch, E., Mervis, C. B., Gray, W. D., Johnson, D. M., and Boyes-Braem, P. (1976). Basic objects in natural categories. Cognitive Psychology, 8, 382–439.

Rumelhart, D. E. and McClelland, J. L. (Eds.) (1986). Parallel distributed processing: Explorations in the microstructure of cognition (Vol. 2, Psychological and biological models) Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Saussure, F. D. (1916). Cours de linguistique générale (Roy Harris, Trans.). London: Duckworth.

Schmitt, N. (2000). Vocabulary in language teaching. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shanks, D. R. (1995). The psychology of associative learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Simpson-Vlach, R. and Ellis, N. C. (2010). An Academic Formulas List (AFL). Applied Linguistics, 31, 487–512.

Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Slobin, D. I. (1996). From “thought and language” to “thinking for speaking”. In J. J. Gumperz and S. C. Levinson (Eds.), Rethinking linguistic relativity (pp. 70–96). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Slobin, D. I. (1997). The origins of grammaticizable notions: Beyond the individual mind. In D. I. Slobin (Ed.), The crosslinguistic study of language acquisition (Vol. 5, pp. 265–323). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Spada, N. (1997). Form-focused instruction and second language acquisition: A review of classroom and laboratory research. Language Teaching Research, 30, 73–87.

Stefanowitsch, A. and Gries, S. T. (2003). Collostructions: Investigating the interaction between words and constructions. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 8, 209–243.

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, J. R. (1998). Syntactic constructions as prototype categories. In M. Tomasello (Ed.), The new psychology of language: Cognitive and functional approaches to language structure (pp. 177–202). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Tomasello, M. (Ed.) (1998). The new psychology of language: Cognitive and functional approaches to language structure. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Tomasello, M. (2003). Constructing a language. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tversky, A. (1977). Features of similarity. Psychological Review, 84, 327–352.

Tyler, A. (2008). Cognitive linguistics and second language instruction. In P. Robinson and N. C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition. London: Routledge.

VanPatten, B. (2006). Input processing. In B. VanPatten and J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical investigations (G. E. M. Anscombe, Trans.). Oxford: Blackwell.

Wulff, S., Ellis, N. C., Römer, U., Bardovi-Harlig, K., and LeBlanc, C. (2009). The acquisition of tense-aspect: Converging evidence from corpora and telicity ratings. The Modern Language Journal, 93, 354–369.

Zipf, G. K. (1935). The psycho-biology of language: An introduction to dynamic philology. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press.