19 Technology and interpretation: aspects of ‘modernism’

In the course of the twentieth century, various technological advances had as radical an effect on the art of opera as the changes associated with ‘modernism’ had on the character of musical composition. Opera at the start of the twenty-first century has become at the same time both more popular and, in a particular but important sense, less popular. The music of the operas of the past is more familiar to the public than ever before – thanks to the invention and refinement of broadcasting and mechanical recording, both aural and visual. The words of operas are better understood by opera-goers than they have ever been, thanks to the introduction during the 1990s of surtitles or supertitles providing simultaneous versions of the text in opera-house auditoria.

Meanwhile, the taste of the public for classical music seems to have been growing ever more retrogressive. In an era when so-called ‘serious’ music broke away from the familiarly melodious and became far more theoretical and experimental, the popularity of new music steadily reduced and music lovers grew less and less amenable to genuine innovation, though new forms of lyrical expression in jazz and rock singing may offer qualification for this verdict. In colour, rhythm and harmony, modern orchestral music has tended to be far more adventurous, and the vocal lines of opera far more unpredictable, than ever before. Yet, contrary to the previous rule (until c. 1900) that the main attraction in operatic repertoires would be new or recently composed works, the rule now is that the public invariably prefers familiar operas – or operas disinterred from the distant past, never before part of the regular repertoire. The latter of course are mostly composed in the highly accessible language of baroque music. The revival of interest in the past which became such a vital factor in the field of commercial recording, and the concern for ‘authentic’ performance practice, have together compensated in part for the popular rejection of contemporary or avant-garde novelty. For the classical record-buying public, the performances of yesteryear are a constant challenge to the achievements of performers today .

Formerly, impresarios knew that commissioning and presenting new works would be the secret to the success of the seasons they mounted, which would often be the leading attraction of the local carnival preceding Lent. In 1900, the Dresden Opera was run by the brilliantly adventurous Generalmusikdirektor Ernst von Schuch, whose long reign in charge from 1872 to 1914 saw a total of 34 world premieres and five German first performances (including Tosca ). In those 42 years, 123 new works were introduced to Dresden audiences, of which a mere 32 would be familiar now. Patrons from Dresden’s well-established English-speaking community could buy a guide to the stories of all operas in the Dresden repertoire: The Standard Operaglass , by Charles Annesley. This was revised and reprinted almost every year from 1887 until the eve of the Second World War. The series includes encouraging critical responses to new operas (in 1897/8, for example, Goldmark’s The Cricket on the Hearth , based on the story by Dickens). A high proportion of these novelties did not remain in the repertoire after the First World War. But a surprising number resurfaced at Wexford after 1972, when that idiosyncratic Irish festival started more consciously to present historical ‘failures’ – the artistic policy for which it became famous. The extremely limited facilities of Wexford’s Theatre Royal, very unlike Dresden’s Semper Opera, seldom enabled justice to be done to these lost works. The ‘judgment of history’ is unreliable.

But in the related fields of operatic production, interpretation and repertoire the modern age has been unlike any previous period in the 400 years of European operatic history. The opera public have been voting with their feet, providing clear commercial evidence (especially in seasons without subscription schemes) that contemporary operas are a taste they are reluctant to acquire. As a result, in the current era which some define or decry as postmodern, what changes from year to year in the opera repertoire commonly encountered is how the works are staged and look, and how their design context relates to and promotes the philosophical themes on which their stories throw dramatic light.

An expensive singers’ market

Another central factor in operatic life at the opening of the twenty-first century is the commercial exploitation of a handful of vocal stars on a worldwide international scale made much easier by modern means of transport. The benefits (and disadvantages) of focused marketing are no different in opera than in any other industry. Enormous sums can be earned by a few artists whose particular capability and expressiveness suit recording. The level of reward otherwise in the world of opera is generally modest, though significantly higher than it was a century ago for such ancillary skills as tailoring, carpentry, wig-making and scene-shifting. However, the disproportionate emphasis on the musical abilities of the greatest stars which is encouraged by modern communications media has a seriously distorting effect on popular taste at the ‘local’ level. Thanks to the increasingly sophisticated technology of the editing suite, there are now inevitably high expectations of accomplishment throughout the population, not just among metropolitan cognoscenti – a by-product of the universal availability of immaculately polished recordings of singers of genius, present and past, in the various entertainment media. Isn’t it wonderful that those dependent on recordings and radio can have such elevated artistry on tap? Altered expectations may have dubious side effects. Live performance is not the same as a recording, of course, but even the greatest stars may be unable regularly to compete with their best edited work – and such assured high-quality interpretation is only occasionally to be encountered among the lower tiers of performers who supply the mass on which the pyramid of excellent accomplishment is necessarily based. As a result, everyday audiences may be increasingly unready to accept everyday standards. That could lead to an increase in the number of sublime performances – but equally it might just reduce the overall size of the live audience prepared to support more homespun endeavour in opera performed live. How much do those dependent on the artifice of recording appreciate the crucial wisdom of Shakespeare’s encomium supplied by Theseus in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (V.1.213): ‘The best in this kind are but shadows and the worst are no worse if imagination amend them’? The reality of twentieth-century technology has long been undermining the whole imaginative ‘culture of amendment’ on which live performance should be able to count .

Opera as theatre

Before the invention of the phonograph there could be no doubt in the mind of the audience that opera was a theatrical art. Wagner was just as self-conscious a theatrical reformer as he was a musical revolutionary. Before the modern age the only way for people to become familiar with an opera away from the theatre was to read its score silently or to play its music on the piano – perhaps accompanying a partial vocal realization. Though many did their ‘homework’ this way, opera was a theatrical experience. The idea of concert performances of opera was almost unknown – though Berlioz’s Trojans , of which the composer conducted extracts at Baden-Baden in 1859, was a rare exception. Thanks to records and recording, during the twentieth century opera escaped from the opera house and became, for many enthusiasts, a purely musical experience – something as private and domestic as reading a novel. That privatization of the operatic experience has been very significant – and thoroughly reflected in the development of operatic taste, or lack of development, in the course of the twentieth century.

Interpretation is no longer a matter of following the dramatic instructions or stage directions suitable to the era when the opera was created. The understanding of the stage as a representation of reality has given way increasingly to a recognition that the purpose of theatrical presentation is not just to tell a story but to employ the live figures and the context as an effective space to focus on the ideas with which the narrative, poetic text and music are concerned. This shift in approach is exactly comparable to the changes in artistic style and objective that can be seen in the development from early nineteenth-century representational painting, through the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists to modern art in its various forms. Interpretation in opera is however constrained by the concern among performers and interpreters involved in stage design and production for the autonomy and content of the work being performed. The popularity of the cinema from the 1920s onwards, with its triumphant ability to represent photographic reality, inevitably made even the most minute attempt at realism in the opera-house, substituting solid sets for the previously predominant painted cloths, seem by comparison like a mere design convention. The conventions of opera are not realistic. The choral singing and confessional solos encourage audiences to develop an objective understanding. Brecht’s desire for telling ‘alienation’ in the theatre had, in fact, just the same motive as Schiller’s wish to restore the chorus from ancient Greek drama to the neo-classical stage. Opera audiences need little prompting to remember that meaningfulness is the fundamental objective.

All these different factors are connected, of course. Exactly which is responsible for what evident unarguable consequences is harder to establish. One thing is not in doubt. The well of new hit operas has run dry since the death of Benjamin Britten in 1976 (his operatic swansong, Death in Venice , was premiered in 1973), and few would disagree that this, partly, reflects the complicated relationship between popular operatic taste and the kinds of non-melodic musical language available to ambitious and creative ‘serious’ composers. There is evidence of a dysfunction exacerbated by the technologies of recording and the ever-increasing mechanization of memory. Live performance no longer fades in the memory of the cultured element of the population – or indeed at all – as it inevitably did before the twentieth century, and that fact has had a large effect on taste.

Decline of the professional opera composer

The crucial question that needs to be posed in any operatic history of the twentieth century must surely be why an era of such progressive development and enhanced musical expressiveness witnessed the disappearance of both the hit opera and the professional opera composer. No twentieth-century composer was as prodigious as

Donizetti (65 operas),

Rossini (39) and

Verdi (28); among the more prolific in modern times were

Britten and Richard

Strauss (15),

Henze (14),

Zandonai (13),

Puccini (12),

Janá ek (9),

Prokofiev and

Schreker (8). The change was gradual, no doubt, but after 1976 it was beyond denial. Is the art of opera therefore doomed to vanish as a result? Is the new obsession with reinterpretation and re-evaluation of operas from the past a sign of decadence or just another stage in the history of ‘reception’? Is song unsullied by mechanical amplification no longer a language and a resource in so-called ‘classical’ or ‘serious’ music for those refined and sometimes challenging composers from whom the ranks of opera makers have always sprung?

ek (9),

Prokofiev and

Schreker (8). The change was gradual, no doubt, but after 1976 it was beyond denial. Is the art of opera therefore doomed to vanish as a result? Is the new obsession with reinterpretation and re-evaluation of operas from the past a sign of decadence or just another stage in the history of ‘reception’? Is song unsullied by mechanical amplification no longer a language and a resource in so-called ‘classical’ or ‘serious’ music for those refined and sometimes challenging composers from whom the ranks of opera makers have always sprung?

The fact that opera audiences supplied with surtitles are in no doubt about the text they are supposed to be hearing has a number of consequences. Composers have never in the past been able to assume that all the text they were setting would be audible. The variable acoustics of different opera-houses have meant that even when a composer had taken pains to adjust the scoring of the instrumental accompaniment to assist singers’ audibility, the text would still not readily be heard in all parts of the house.

Surtitles can translate operas that are being performed in a foreign language, and sometimes even provide a written-out version of text being sung in the audience’s vernacular. The balance between the elements that make up a satisfying operatic experience is consequently altered, with results as yet unmeasurable. In the past not being so accurately supplied with the text did make for a special kind of audience responsiveness to the overall effect an opera could achieve. So one result of surtitles is to constrain the audience’s licence to imagine and be inspired – drawing on other communicative factors of the operatic and theatrical manifestation coming to them from the stage. Surtitles are a potent new technology and may be a dangerously two-edged sword. They compensate for the declining ability of ageing audiences to listen to and hear the words being sung. They make up for the regrettable difficulty singers face – frequently required to perform in a language whose nuances they do not understand properly and whose sound patterns they have had to learn parrot-fashion – in getting the sung text to communicate as language should. In Handel’s London the opera-house auditorium was candle-lit throughout the performance. English word-books of Italian libretti were on sale to help the public cope with the language barrier. The facility of simultaneous translation therefore satisfies a not unprecedented audience desire, hitherto technologically impossible to fulfil, to understand perfectly the experience being witnessed. Naturally surtitles are overwhelmingly popular, though they may lower the theatrical temperature, and they certainly do alter the way audiences listen to the text being sung – with meaning filtered through a written medium that inevitably lacks the subjective expressive qualification supplied by a subtle, sensitive singer-actor.

Original-language performance

Another likely result may be greater internationalization of opera as a live theatrical experience, and confirmation of the primacy of original-language performances. This is already observable in Germany and Italy, where large native repertoires of opera existed for centuries and some companies until the last decade of the twentieth century generally performed most of their repertoire in translation. In April 2004, the Leipzig Opera gave Jonathan Dove’s Flight its first production sung in German. But the French-Swiss Intendant of the newly built and much smaller 800-seat Erfurt Opera (opened in September 2003 at a cost of 60 million Euros), nearby in Thuringia, launched a new policy of performing always in the original language using surtitles – a major change for what was formerly the German Democratic Republic, where Walter Felsenstein’s commitment to prominent theatrical values at the Berlin Komische Oper had always set a powerful example. For language-cultures or nations which have not already created a native operatic repertoire, the availability of surtitles is likely to make it much harder for the art of opera to be naturalized and incorporated into the native repertoire as Shakespeare in the eighteenth century was accepted and recognized in Germany because contemporary translation into German had made him a part of German literature and theatre. Considering the role played by the Reformation and vernacular Bible in European culture, the promotion and almost universal acceptance of the principle that opera is best performed in the composer’s original language seems both ironical and perhaps in need of robust questioning.

The existence of Lilian Baylis’s London opera company committed to performance in English, first at the Old Vic and then at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, without doubt helped to sustain a climate in England favourable to English-language opera, without which Britten’s genius might not have been so easily able to flower. Baylis was following a path already well-trodden by the Carl Rosa company. The ecology on which new opera depends is complex. The idea that operas are composed in one language and should not ideally be displaced from that language into another runs counter to the clearly expressed preference over the centuries of many great opera composers of the past (Mozart and Verdi, for instance). It undermines an understanding of opera as a collaborative theatrical art-form demanding in performance various creative compromises. Surtitles reinforce the impression created by opera on CD, DVD and video, that opera should be idealized as a museum art-form, something to be appreciated and worshipped rather than adapted and used.

A pantheon of geniuses

In 1800 the idea of an international operatic repertoire containing a pantheon of masterpieces was just starting to emerge. By 1900, Mozart, Verdi and Wagner were universally recognized as the presiding deities of a mature art-form to which a limited roster of composers based in five distinct European language-cultures had contributed what appeared indestructible classics. Bizet’s

Carmen

was one of the most outstandingly popular works.

Puccini’s

Bohème

was just entering the firmament. A century later, in 2000, little had changed in the established operatic pantheon. The popularity of Puccini is inextinguishable. His operas still define basic popular taste a century after their creation. That ironical and significant indicator says much about the history of the art-form. As a generator of modern repertoire masterpieces, Puccini has been joined by perhaps four other composers capable of making a substantial impact: Strauss, Janá ek, Britten and Prokofiev. In terms of audience rating and commercial viability Puccini reigns supreme, as he has done ever since 1926 when he died leaving

Turandot

unfinished. The twentieth century saw many opera composers submit themselves for public approval, like Turandot’s suitors, but none displaced the achievement of Puccini – however regrettable if not disgraceful that fact has appeared to some academics and progressive impresarios. Joseph

Kerman’s dismissal of

Tosca

in his seminal Opera as Drama

(1956, 13–16) was later echoed in Gerard

Mortier’s refusal to programme a single work by Puccini during his twenty consecutive years at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels and then at the

Salzburg Festival

.

ek, Britten and Prokofiev. In terms of audience rating and commercial viability Puccini reigns supreme, as he has done ever since 1926 when he died leaving

Turandot

unfinished. The twentieth century saw many opera composers submit themselves for public approval, like Turandot’s suitors, but none displaced the achievement of Puccini – however regrettable if not disgraceful that fact has appeared to some academics and progressive impresarios. Joseph

Kerman’s dismissal of

Tosca

in his seminal Opera as Drama

(1956, 13–16) was later echoed in Gerard

Mortier’s refusal to programme a single work by Puccini during his twenty consecutive years at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels and then at the

Salzburg Festival

.

The contemporary composer is free to write anything, since there is no common ‘serious’ musical language. Yet freedom can be a burden. Those composers who have been drawn to opera or music theatre lately have had to find for themselves a personal but appropriate lyrical language – not an easy task considering the limited contemporary market for songs or song-cycles. Song is the fundamental tool of opera, because the song or aria conveys in a unique way both the intimacy and the interiorness that are paradoxically the special core of operatic theatricality. Human song is the emotional arrow that reaches each member of the operatic audience – conveying an implacable truth of feeling. The aria supplies the equivalent in communicated intimacy to the cinematic close-up. Britten notably wrote many songs, as well as operas. Stravinsky, too, often composed for the voice, though he wrote few conventional operatic works. Both possessed a strikingly distinctive yet completely different lyrical voice. To be effective as a composer of opera requires an ability to create an effective single musical line. Line drawing is not a discipline in which every successful modern painter can excel. Lyrical specialization is equally something particular that requires a certain ear and a desire, qualities that are not necessarily relevant assets for the contemporary composer writing for instrumental ensemble or keyboard. As the common lyrical language of earlier times grew more and more distant and faint, many new operas have simply not registered in the memory as an experience of song: Richard Rodney Bennett and Stephen Oliver, for example, each had a flair for light music (night-club songs and theatre incidental music that recollected the accessible popular-song language of thirty years earlier), but each suffered significant lyrical inhibition when tackling ‘serious’ work. Yet, if the last quarter of the twentieth century was the least fertile period of successful operatic composition in operatic history, that does not mean all is over for the art-form. Opera has always had far more failures than successes in the ranks of newly composed works. The potential of music theatre has always been problematic.

Meanwhile, many new operas have continued to be written. The twentieth century was rich in singleton masterpieces of which Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s

Die Soldaten

(1960) is a prime example, and the development of the art-form in terms of musical language and new subject-matter has been as intriguing as the observable switch in production style from more or less dutiful naturalism to a kind of morally loaded surrealism. Instead of pursuing basic narrative, many opera productions nowadays are led by a governing concept. However, the circumstances of composition have changed radically, and this change in the industry of opera-making has come about at widely different times in each of those few language-cultures that formerly were the operatic factories of the world. Though

Janá ek was properly recognized in his native Czechoslovakia only in his old age, it was some decades after his death before he became truly popular in, for example, Britain and Belgium.

(In the Brussels Opera,

Mortier placed Janá

ek was properly recognized in his native Czechoslovakia only in his old age, it was some decades after his death before he became truly popular in, for example, Britain and Belgium.

(In the Brussels Opera,

Mortier placed Janá ek’s name in the redecorated auditorium alongside those of Mozart and Wagner when the house was totally refurbished in 1985–6.)

Britten’s status and achievement began to be accepted in Germany very soon after his works achieved widespread recognition and popularity in Britain in the 1960s. But he was not properly acknowledged in France until another quarter of a century had passed.

Henze is prolific but has scarcely become a popular operatic composer even within the German-language opera world with its enviable total of more than eighty opera companies. The most obvious reason for that is probably Henze’s difficulty creating memorable melodic material that can be attached to the individual character.

ek’s name in the redecorated auditorium alongside those of Mozart and Wagner when the house was totally refurbished in 1985–6.)

Britten’s status and achievement began to be accepted in Germany very soon after his works achieved widespread recognition and popularity in Britain in the 1960s. But he was not properly acknowledged in France until another quarter of a century had passed.

Henze is prolific but has scarcely become a popular operatic composer even within the German-language opera world with its enviable total of more than eighty opera companies. The most obvious reason for that is probably Henze’s difficulty creating memorable melodic material that can be attached to the individual character.

It is not that the public cannot respond to the idiosyncratic but wonderfully expressive song-language of Berg’s Wozzeck and Lulu , or of Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron . Critics in the 1950s and 1960s, when serial composition was seen as the best way forwards, often attacked the melodious and highly accessible musical languages of Strauss and Prokofiev – though both coexisted with Berg and Schoenberg in the esteem of professionals quite happily until around 1950. The issues of memorability and singability were both consciously confronted by Prokofiev, as part of his attempt to perform a creative duty to his native Russia. Later in the 1950s, by contrast, Stravinsky consciously adopted dodecaphonic techniques in place of his previous neo-classicism. Would The Rake’s Progress have been possible at all, if Stravinsky had changed his language earlier? Pastiche was not artistically respectable in the twentieth century. Yet progress, or at least advancing, often depends on being able to retrace steps. There are kinds of melodiousness that affect the public and kinds that do not – and melody is not all, as the composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim has suggested, a matter of familiarity with the specific notes. In an interview with the author in London in 1973, Sondheim explained about Leonard Bernstein’s songs in West Side Story , which he claimed were originally considered untuneful, and for which he wrote the lyrics: ‘the movie came out [in 1961], and the movie company wanting to protect their investment put many thousands of dollars into the promotion. Soon as the public started to hear the songs more than once, lo and behold they could suddenly whistle them . . . Tunes are a matter of hearing, of familiarity. You can whistle or hum anything if you hear it enough times. That’s all .’

Perhaps precisely because of the melodic handicap with which the modernist and avant-garde movements fettered the language of lyricism, there was a premium on operatic originality and creative responsibility and a readiness to accept that the operatic form could pursue different objectives and function in different ways. The popularity of the youthful

Shostakovich’s remarkable

Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

(1934) was highly unusual and was proved by the 200 performances to cheering Soviet audiences during the two years after its premiere before Stalin banned it. In the 1920s and 1930s a popular market for new opera still existed in those language-cultures where opera had been pioneered – Germany and Italy.

Britten’s achievement in creating a repertoire of masterpieces for an English culture barely used to opera as a popular form was remarkable. The English-speaking world entered the opera business at almost the last moment when it was possible to do so – when the language of song was still available, and when in Britain and the USA there was an audience for new work. Both in dramatic structure and in subject matter some twentieth-century operas broke away from traditional models, and tackled unprecedented subjects. But critics of course mostly shared the taste of the public they served, rejecting avant-garde modernism. Unsurprisingly, the appetite of impresarios and companies for newly composed work and risky financial novelty declined rapidly after the 1950s. In the final quarter of the century John Adams’s

Nixon in China

was almost the only opera that looked likely to enter the popular repertoire – a status confirmed by the decision of English National Opera to re-open the refurbished Coliseum with it in February 2004. The musical languages of Britten and Janá ek were still considered challenging and inaccessible in the 1980s by ordinary opera-goers. Yet both Schoenberg and Berg in the 1920s and 1930s had shown that expressive melody need not be vocally graceful in a traditional sense. Right through the twentieth century operas were being successfully premiered that had distinctive individuality and achieved some recognition – from Debussy’s

Pelléas et Mélisande

(1902) onwards.

Wozzeck

was rapidly recognized as original, confident and economical, both musically and dramatically, yet its composer famously declared (Berg

1927

) that it should not to be regarded as setting a new path for operatic composers.

ek were still considered challenging and inaccessible in the 1980s by ordinary opera-goers. Yet both Schoenberg and Berg in the 1920s and 1930s had shown that expressive melody need not be vocally graceful in a traditional sense. Right through the twentieth century operas were being successfully premiered that had distinctive individuality and achieved some recognition – from Debussy’s

Pelléas et Mélisande

(1902) onwards.

Wozzeck

was rapidly recognized as original, confident and economical, both musically and dramatically, yet its composer famously declared (Berg

1927

) that it should not to be regarded as setting a new path for operatic composers.

The question of modernist musical language dominated the business of new opera until the onset of minimalism, which at least restored a recognizable and variable melodic option for composers, though not quite the old techniques of conscious tuneful variation that characterized classical music until the advent of strict serialism. The problem for opera composers has always been to adapt their personal musical language to the definition of individual character through specific arias. At all stages of operatic history it has been true that characterization has depended on the confessional role of the aria. An insufficiently graspable melodic language is not a good tool for developing characterization. The respective musical palettes of Berio, Ligeti, Nono and Dallapiccola have found various beautiful solutions to the problem. But Britten and Tippett (and a few others) in the 1950s and 1960s were increasingly isolated because of their commitment to melody. What a character in opera can and should sing, and what a character in spoken drama can and should say, are similar creative issues. Recognition of precisely who the role is on the stage has always depended on a linear musical language that can underpin and qualify text adaptably and on the composer’s skill at moulding memorable musical statements with the capacity to be conversationally variable. But thereafter the modernist agenda associated with Darmstadt and Donaueschingen helped create and sustain an anti-melodic conformism: diatonic methods were seen as totally outdated, and many opera composers felt obliged to try and be ‘modern’ – in other words, dodecaphonic. When he was composing his opera Clarissa in August 1974, Robin Holloway wrote (in a letter to the author) of ‘the prohibitions of my musical education . . . those implied by a particular climate – whose nature I indicated by quoting the widely-held (at that time) dismissal of Berg as “12-note Puccini” . . . The “modern” (that is, the current state of music, the consensus, the orthodoxy) forms, the modern modes, don’t allow enough to be expressed.’ When Clarissa (which Holloway wrote uncommissioned, so passionate was he about the subject) was premiered in 1990 at English National Opera, the problem with lyrical projection to which he was referring here was crystallized in the difficulty he had finding a suitably melodic and singable manifestation for Loveless’s dubious romantic seductiveness .

Popular interest in new opera continued to wane throughout the twentieth century – though in the USA the end of the century saw a sea change in support for new work, reflecting the New World’s sense of identification with modern endeavour. After 1950 no new professional opera composers entered the market, no bankable names turning out a succession of popular and recognized achievements. In previous centuries there always were a few composers with the gifts of melody and theatrical timing who successfully took up operatic composition. Today there is no obvious Donizetti, though perhaps Dove has shown signs of a potentially prolific lyrical language. Philip Glass’s operas are singable and depend on ghosts of diatonicism, but they create atmosphere more than memorable or characterful arias. Since the death in 1981 of American composer Samuel Barber, with his unforgettable contributions to the corpus of poetic English art-song, no composer in any language-culture seems to have made a mark as being able to compose expressive and genuinely singable songs in music that could be taken seriously – in other words in material that was not merely a reproduction of the style of tunes from the past. André Previn’s opera A Streetcar Named Desire (1998) suffers from an overwhelming sense that it is the musical equivalent of reproduction furniture – it feels fake.

New themes and contemporary problems

The emphasis in nineteenth-century opera plots on romantic tragedy as it affected various levels of society was developed thematically in two main directions in the twentieth century.

Britten in most of his operas, for example, touched delicately on the hitherto unmentionable topic of

homosexuality – though the issue was seldom overtly raised.

Janá ek’s operas shared a concern with women’s position in society. And once the real seriousness of opera seria

had been recognized, and baroque operas generally were being taken seriously on their own terms rather than disparaged for not being as modern or cinematic as Puccini’s operas or some nineteenth-century works, it was possible to see how obsessive the theme of the nature of power and the inability of the powerful to rule the heart was to the eighteenth century. Thus, while Puccini reigned supreme, an alternative history was at the same time increasingly honoured thanks to the early-music movement – and to the effect of authentic musical performance on the modern popularity of great, historically significant figures like Lully, Rameau, Handel, Hasse and Jommelli.

ek’s operas shared a concern with women’s position in society. And once the real seriousness of opera seria

had been recognized, and baroque operas generally were being taken seriously on their own terms rather than disparaged for not being as modern or cinematic as Puccini’s operas or some nineteenth-century works, it was possible to see how obsessive the theme of the nature of power and the inability of the powerful to rule the heart was to the eighteenth century. Thus, while Puccini reigned supreme, an alternative history was at the same time increasingly honoured thanks to the early-music movement – and to the effect of authentic musical performance on the modern popularity of great, historically significant figures like Lully, Rameau, Handel, Hasse and Jommelli.

The new radically different attitude towards past performance practice tempered any temporary triumph of serialism after 1950. There had been scholarly historical research for a century, of course. The obsession of opera before 1900 with new work was not shared by the Roman Church, for instance, whose musical policies ensured Palestrina never vanished from the current repertoire in the way Bach did, until revived by Mendelssohn. Chrysander’s Händel-Gesellschaft edition of Handel’s operas (1868–85) preceded by many decades the performances staged at Göttingen and Halle in the 1920s. But it was the arrival of Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea at Aix-en-Provence, Glyndebourne and La Scala, Milan, in the 1960s that really set the seal on the process of opening up the long-abandoned seam of old operatic works which has turned out to contain many treasures, including some indubitable masterpieces. This could have increased the sense of opera as being stuck with a ‘museum’ repertoire, but instead the rediscovered old works invited and merited theatrical treatment as if they were new and ‘contemporary’ – partly because their music and text, not always fully preserved or defined, is of unstable provenance. These are works history really forgot. Older operatic forms have often proved especially well suited to non-naturalistic and surrealistic stagings – which seem to release their theatrical quality even more convincingly. Theatre history is cyclical. Monteverdi is closer to Shakespeare and Ben Jonson and certainly a long way from the well-made play of the early twentieth century. The relocation, updating and transportation of mythical and classical material into contemporary garb which became commonplace in opera staging after 1976 were not unprecedented. Costumes in the theatre before the nineteenth century’s concern for historical reality became paramount were usually contemporary, though outlandish or classical characters or clowns (especially the stock and beloved figures of commedia dell’arte ) were dressed in a way that indicated their nature or role, as well as their different and foreign origin. A 1709 print shows the Ghost of Hamlet’s father in medieval armour, but the prince himself in a periwig. David Garrick’s mid-eighteenth-century performances of Shakespearean tragedy used contemporary dress, with perhaps a stronger realistic intent than would have concerned actors in Shakespeare’s day. Like modern painters and sculptors, modern composers have been drawn to ethnic examples – writing music whose rhythm and dissonance initially seemed to relate to alien models.

Unpredictable benefits of deconstruction

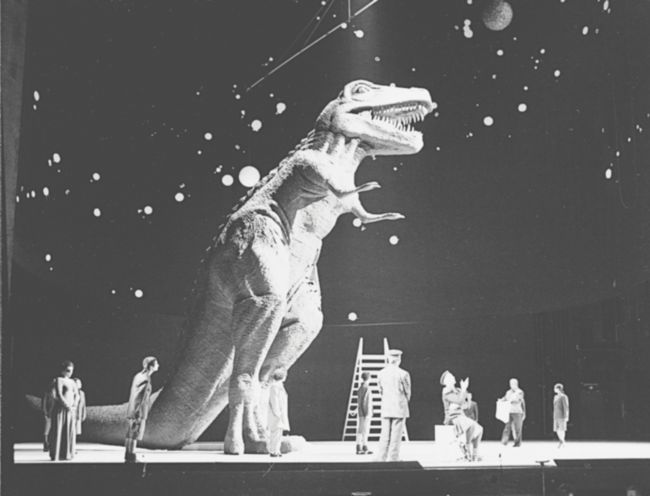

Early attempts to revive Handel’s operas treated their staging as if they were unsatisfactory attempts at verismo . Only when daring live productions played conceptual postmodern jokes with the material could Handel’s and Monteverdi’s innate theatricality be fully recognized in design contexts unembarrassed by their non-naturalistic emphasis on ‘confessional’ material. Hence the giant toy dinosaurs in Richard Jones’s and Nigel Lowery’s hit Munich 1994 production of Giulio Cesare in Egitto (see Figure 19.1 ). Arias in the opera seria need a backdrop, not a narrative moment: they are just as effective at energizing the drama as the business of a through-composed operatic scene. Aspects of operatic interpretation affected by ‘modernist’ changes include singing styles (Sprechstimme ), scenery (cubism and constructivism) and acting (the Stanislavsky ‘method’ with its emphasis on truthful psychological naturalism, and the cinema with its rejection of emphatic overstatement often previously common in theatrical performance). ‘Modernism’ has imposed tough responsibilities on the creators of the genuinely new in the world of opera.

Figure 19.1 Handel’s Giulio Cesare in Egitto , directed by Richard Jones and designed by Nigel Lowery (Bayerische Staatsoper, 1994). Photo: Anne Kirkbach, reproduced by permission of Wilfried Hösl.

Naturally the appetite of opera audiences had to be titillated in new ways once the decline in successful and popular newly composed operas became overwhelmingly evident. In fact, new operas have always been a gamble, though new performers have often quite rapidly become bankable assets for impresarios. The Age of the Director is how the last quarter of the twentieth century has been defined by most commentators – whether they were deploring or praising the fact – and the rise of directors has certainly enabled a significant section of the opera public to appreciate being provided with novelty in a number of ways. Operas subject to ‘interventionist’ stagings have revealed depths and shadows not always recognized earlier. The encounter with Handel’s operas and oratorios in the theatre was strikingly popular and successful in the 1980s and 1990s, progressing into an inventive, irreverent, even farcical theatricality that endorsed the genius of the works in brand-new ways. Stagings like Nicholas Hytner’s and David Fielding’s Xerxes at English National Opera (1985) were based fundamentally on the revaluation of how Handel’s operas actually function in dramatic context. The newly extended operatic repertoire at the end of the twentieth century embraced operas generally ignored for centuries from before the age of Gluck and Mozart, new but old, as well as defamiliarized new productions of never-fading popular works, old but new. This reflected the emphasis opera companies typically were now placing on reinterpretative staging and conceptual revaluation, together with the value of defamiliarization as an interpretative discipline.

It is a significant coincidence that the year in which Britten died also saw the unveiling of Patrice Chéreau’s centenary production of Wagner’s Ring at Bayreuth, designed by Richard Peduzzi and Jacques Schmidt. This was conducted by the leading guru and intellectual of the musical avant-garde in Europe, Pierre Boulez, who only a few years earlier had called for opera houses everywhere to be blown up in an orgy of revolutionary fervour (though Boulez would not have wanted the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, where he in 1965 conducted Wieland Wagner’s influential 1951 staging of Parsifal , to go up in flames). Chéreau’s radical and, at the time, ferociously controversial deconstruction of Wagner’s Tetralogy along Shavian-cum-Marxist lines ushered in a period in which opera staging was considered by many to be the most interesting and rewarding factor in the whole operatic experience.

Concern for meaningful representation of operas in the theatre has gone beyond the basic desire for convincing naturalism and dramatic truthfulness associated with the Vienna Opera reforms of Gustav Mahler and Alfred Roller. Anton Webern described Roller’s Tristan und Isolde in his (unpublished) diary on 21 February 1903:

The orange-yellow of Isolde’s tent creates a lightness which contrasts wonderfully with the bright blue light shining on the sea in the distance. The second act decor is fascinating. A warm summer night, very dark blue, lit by the moon, breathes its magic onto your face. Violet shadows slip over the terrace and the house walls. The stone parapets of the terrace are entwined with superb flowers which surround the bench where the lovers are to sit . . . The whole setting of the last act is full of endless sadness and despair. Under the great knotted limetree the hero lies suffering. The ground slopes, with the castle gate lower down at the back. Scattered stones and the debris of crumbling walls lie about.

(Moldenhauer archives, Spokane, Washington, DC)

Roller’s point, as elaborated in the almanac Thespis: Das Theaterbuch ( 1930 ), was that ‘The stage does not provide a “picture”; it provides spaces, appropriate to the playwright’s work and to the actors’ words and gestures . . .’ Earlier, in an article entitled ‘Bühnenreform’ (1909), he wrote:

Production is, after all, the art of presentation, never an end in itself . . . ‘Do you favour stylization or illusion?’ one is continually asked, ‘three-dimensional sets or backdrops?’ – just as at table one is asked, ‘Would you like white wine or red?’. . . Each work of art carries within itself the principles of its production. – Rules and methods established today can be stood on their head by a poet who comes along and creates a work tomorrow. Should he be prevented? In Shakespeare they speak the scenery. Genius can look after itself.

(Sutcliffe 1996 , 429)

The Sezession architect and designer Adolf Loos, as he reminisced in his diary-memoirs ( 1931/2 ), found the opening act of the famous Mahler–Roller Tristan so lavishly detailed and obtrusively familiar that he could not bear to stay for the rest, conscious that ‘The carpet is Rudniker (Prague). I’ve used them too. For the entrance hall. All those cushions look nice .’

Defining the limits of naturalism

In modern times, stage representation has developed in broadly two directions, towards abstracted purification on the one hand or surreal intensification on the other. Neither displaced the desire to give opera as much theatrical credibility and lifelike potency as possible: very necessarily, since opera is in itself such an essentially unreal and non-naturalistic form of theatre where what is sung is the most important and effective element. During the first decades of the century, the conviction was crystallized by the writings and limited practice of Adolphe Appia and Edward Gordon Craig that the focus of any theatrical and operatic experience would be strengthened if the trappings of naturalism were replaced by epic architectural set-designs combining platform-like monumental spaces with expressive, carefully coloured and shaded lighting. Appia only had the chance to apply his theories in Milan and Basel in the 1920s. Doing without the overt imitation of naturalistic designs can emphasize the human relationships – enhancing the focus on the individual character’s singing of arias and duets which is already apparent in opera. Experimenters in Moscow (both before and after the Communist Revolution) and elsewhere demonstrated both the benefits and the disadvantages of non-realism to those few pioneers who were interested. After staging Tristan und Isolde at the Mariinsky, Meyerhold wrote: ‘The better the acting, the more naive the very convention of opera appears; the situation of people behaving in a lifelike manner on the stage and then suddenly breaking into song is bound to seem absurd’ ( 1910 ). Max Reinhardt’s devotion to theatrical realism was not about imitating life in a cinematic way but seeming truthful and convincing and imaginatively diverting – in other words mobilizing the ‘magic’ of the theatre. Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danchenko took little notice of Appia at the Moscow Art Theatre or at the Bolshoi’s opera studio.

An engine of innovation in Germany

Otto Klemperer’s innovative but not very popular Berlin regime at the Kroll Opera achieved some telling collaborations with avant-garde artists as designers. If the scene was structural in layout rather than representational, that would concentrate the audience’s attention and avoid the distraction of inessential detail. Ewald Dülberg designed a set for Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer with platforms and ramps, rather than anything very shipshape, and Jürgen Fehling was a theatre director making his debut in opera, and no Wagnerian. Paul Schwers, critic of the Allgemeine Musikzeitung , wrote on 25 January 1929: ‘The Dutchman, naturally beardless, looks like a Bolshevist agitator, Senta like a fanatical . . . Communist harridan, Erik . . . a pimp. Daland’s crew resemble port vagabonds of recent times, the wretched spinning chamber a workshop in a women’s prison.’ The staging was ‘a total destruction of Wagner’s work, a basic falsification of his creative intentions.’ László Moholy-Nagy, a month later, offered geometrical constructivist sets for The Tales of Hoffmann that were intended to ‘create space out of light and shadow . . . an elaborate pattern of shapes’ ( 1929 , 219). Ernst Bloch loved the identification of Hoffmann’s eerie, ghostly world with machinery (Der Querschnitt , March 1929).

The greatest demonstration of the benefits of non-naturalism came in the 1950s with Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner’s ‘New Bayreuth’ productions of their grandfather’s operas. A noble simplicity swept away many of what seemed undesirable Nazi associations. But once opera stories were freed from the mundane needs of narrative realism, and their philosophical themes were more nakedly exposed, it was only a short step to deconstruction – combined with a playful, surrealistic and sometimes satirical exploration of the ideas within operas. Opera productions associated with the new generation of directors from the 1970s onwards recognized how variations in location and period, and other kinds of subtextual association, could radically change the design environment and deepen the complexity of the theatrical process of interpretation.

Attempts to trace a coherent line of development in twentieth-century operatic staging – notably in the New Grove Dictionary of Opera (Sadie 1992 ) – have comparatively little to go on. Of course the history of opera and theatre design is well illustrated. What is harder to establish from the early decades of the century, before visual recording became more commonplace, is evidence of change, and the nature of the differences, in the acting of the best operatic performers. The drawing of conclusions is thus rather an artificial game which ignores how few experiments that were written about were either carried off successfully or imitated widely. However, changes in theatrical style that became commonplace during the last quarter of the twentieth century, and not only in Wagner or at Bayreuth, were not unprecedented. Theories about ‘illusionism’, ‘naturalism’, ‘symbolism’ and ‘expressionism’ tend to ignore the common practice, which was overwhelmingly conservative. Photographs and critical response demonstrate this. Thanks to the power of operatic music, especially when its narrative context was tragic, a desire for emotional truth and narrative realism usually went along with a sense of epic dignity. Directors like Visconti, Strehler and Felsenstein pursued good acting and psychological realism on the opera stage and saw the benefit of a degree of pictorialism. Although Dali, De Chirico and Picasso designed ballet sets, the surrealism of Magritte was not an influence on stage sets in opera until the 1980s and 1990s.

The decline in the quantity of successful new work emphasized the sense that opera was a finite resource – involving a pantheon of significant masterpieces. A necessary repertoire for the student and enthusiast was already recognized and largely established at the end of the nineteenth century. It has been further developed since the Second World War, with substantial representation from before the time of Gluck and a good number of twentieth-century works. This material was well served in the last twenty-five years of the century by a great number of ‘interventionist’ productions, re-interpreting and re-evaluating.

Chéreau’s Ring at Bayreuth in 1976 was in many ways a romantic approach – though not in the nineteenth-century sense. It preserved and emphasized the heroic status of Siegfried in a glamorous way. It did not update the story in a precise fashion to any particular era, but in its costumes and sets it referred the audience to the period of the work’s first performance (this being a celebration of the centenary of that event) and to subsequent decades when conflicting theories about economic power lay behind major wars and politics generally. In Das Rheingold and Die Walküre , Wotan wore a frock coat. In Götterdämmerung , Siegfried wore a dinner suit. As a follower of Strehler, Chéreau took pains to achieve an unforgettable metaphysical atmosphere for the Todesverkundigung scene with ominously dim lighting. Partly because of Wagner’s status as a theatrical revolutionary, and because of the attention paid to the ‘New Bayreuth’ ethos after the war, different productions of The Ring at the time of the centenary and afterwards provided a broad spectrum of the ways that operatic staging was changing. It would be absurd to define an opera production merely in terms of the unusual costumes it contained. But productions of The Ring by Ruth Berghaus designed by Axel Manthey in Frankfurt (1985–7), by Herbert Wernicke in Brussels (1991) and by Richard Jones in London (1994–5) concurred in visualizing Siegfried for his scenes with Mime in shorts or lederhosen, then had him smartening up into a suit of sorts for Götterdämmerung . Jones’s Wotan (as created by Nigel Lowery, perhaps the most unusual and visually accomplished of postwar British stage designers) was a sort of lollipop man, carrying a road sign instead of a spear (as if he were providing oversight and safe passage for ‘schoolchildren’ crossing the road) . Directors such as Christoph Marthaler and Jossi Wieler were inclined at the end of the century to relocate every opera they staged in a present-day office environment or on a contemporary housing estate. The tyranny of the single set was theatrically frustrating sometimes – though it may have made sense financially. It was a fact of operatic life at a time of declining subsidies that it would be cheaper to fit out a whole chorus in contemporary clothes than in newly made period costumes. Peter Sellars usually put his opera productions in some often telling contemporary American context, though he did not help The Rake’s Progress by setting it in a modern-day American penitentiary (1996). Jonathan Miller’s Rigoletto at English National Opera (1983) was transposed to New York’s Little Italy and became a tale of a lecherous but charming mafia boss.

Recycling the design tradition

Freedom to choose an environment entirely different in period and in location from that conceived originally by the composer and librettist is not such a break with tradition. If Verdi could move Un ballo in maschera from Stockholm to New England in order to satisfy the censors, it is hard to see what fault he would find with Miller’s mafia spin on Rigoletto . For designers, directors, conductors and dramaturgs, variation in where and when the story is being unfolded is much less significant than the opportunities for revealing focus and unusual theatrical dynamics provided by the permitted or tolerated new approaches to interpretation. Different is by no means always better, but defamiliarization can often be a fertile way of shining new shafts of light into the heart of a familiar work. Familiar is after all only a comparative term. New operas in the twentieth century have not so often needed reinterpretation. Yet even a work like Peter Grimes proved to hold far more ambiguity than might have been suspected when staged by Willy Decker at the Monnaie in Brussels in 1994 (see Sutcliffe 1996 , 406–12). The purpose of opera and of operatic interpretation in the theatre is to make the audience inhabit the material in a new way and think freshly about what the music and drama mean. The choices that interpreters may now make without constraint are also liberating for those trying to compose new operas with serious subjects and staying power. Opera has in a way much greater freedom in its staging precisely because it is not primarily a realistic or straightforwardly narrative form. In a sense, in opera, every production is a footnote to the musical definition of a community of characters engaged in mutual confession. The issue of how much sense a production makes partly depends on the readiness of the audience to lend imaginative consent to what is on offer.

An obsessive respect for the works of the past may have created a more debilitated operatic world. But it is hard to see audiences doing without the repertoire of masterpieces on which they now feed, even if a new era of creativity and fresh operatic composition ensues. A past that belongs to Handel, Mozart, Puccini, Rossini, Tchaikovsky, Verdi and Wagner – not to mention such modern masters as Adams, Adès, Barber, Barry, Bartók, Birtwistle, Bliss, Blitzstein, Britten, Busoni, Copland, Dallapiccola, Maxwell Davies, Dessau, Dukas, Enescu, Fall, de Falla, Fauré, Floyd, Gerhard, Gershwin, Goehr, Hindemith, Holst, Kalman, Knussen, K enek, Korngold, Lehár, Martin

enek, Korngold, Lehár, Martin , Messiaen, Milhaud, Osborne, Poulenc, Ravel, Respighi, Rota, Schreker, Thomson, Tippett, Turnage, Walton, Weill, Weir, Wolf-Ferrari and Zemlinsky (to name just a few) – is unlikely to be displaced by future novelty.

, Messiaen, Milhaud, Osborne, Poulenc, Ravel, Respighi, Rota, Schreker, Thomson, Tippett, Turnage, Walton, Weill, Weir, Wolf-Ferrari and Zemlinsky (to name just a few) – is unlikely to be displaced by future novelty.