F.T. That was a very nice touch. There were many other visual innovations in the picture. The story was about a triangle, with frequent references to original sin, and I still remember that you used a snakelike bracelet as a symbol in several different ways.II

A.H. These things were noticed by the reviewers and the picture had a succès d’estime, but it was not a commercial hit. This is also the film in which I introduced a few notions that were widely adopted later on. For instance, to show the progress of a prize fighter’s career, we showed large posters on the street, with his name on the bottom. We show different seasons—summer, autumn, winter—and the name is printed in bigger and bigger letters on each of the posters. I took great care to illustrate the changing seasons: blossoming trees for the spring, snow for the winter, and so on.

F.T. Your next picture, The Farmer’s Wife, was adapted from a light play about a widower who lives on a farm with a housekeeper and is combing the countryside for a new wife. After some disappointing experiences with three matrimonial prospects, he realizes that his housekeeper, who naturally has been secretly in love with him all along, is the ideal choice and so they get married.

A.H. Yes, that was a comedy that ran on the London stage for something like fourteen hundred performances. There was too much dialogue. It was largely a title film.

F.T. As a matter of fact, some of the best scenes were probably the screen additions to the original play. Among the highlights I remember is one sequence in which the servants in the pantry gorge themselves on food intended for the guests at a reception. And Gordon Harker was particularly funny as the old farm hand. I might add that the setting recalls the Murnau films. The photography also suggests the German influence.

A.H. It’s possible. When the chief cameraman got sick, I handled the camera myself. I arranged the lighting, but since I wasn’t too sure of myself, I sent a test over to the lab. While waiting for the results, we would rehearse the scene. I did what I could, but it wasn’t actually very cinematic.

F.T. Just the same, the way in which you handled the adaptation from stage to screen reflects a tenacious effort to create pure cinema. At no time, for instance, is the camera placed where the audience would be if the shooting had been done from the stage, but rather as if the camera had been set up in the wings. The characters never move sideways; they move straight toward the camera, more systematically than in your other pictures. It’s filmed like a thriller.

A.H. What you mean is that the camera is inside the action. Well, the idea of photographing actions and stories came about with the development of techniques proper to film. The most significant of these, you know, occurred when D. W. Griffith took the camera away from the proscenium arch, where his predecessors used to place it, and moved it as close as possible to the actors. The next major step was when Griffith, improving on the earlier efforts of the British G. A. Smith and the American Edwin S. Porter, began to get the strips of film together in sequence. This was the beginning of cinematographic rhythm through the use of montage. I don’t remember too much about The Farmer’s Wife, but I know that filming that play stimulated my wish to express myself in purely cinematic terms.

What comes after The Farmer’s Wife?

F.T. The next one was Champagne.

A.H. That was probably the lowest ebb in my output.

F.T. That’s not fair. I enjoyed it. Some of the scenes have the lively quality of the Griffith comedies.

It can be summed up in a few words: A millionaire father objects to the man his daughter is in love with and the girl leaves home and sails to France. To teach her a lesson her father allows her to think he’s bankrupt, so that she will have to make her own living. The heroine goes to work in a cabaret, where her job consists of encouraging the clientele to drink the very same champagne to which the family owes its fortune. Eventually, the father, who’s had a detective keeping an eye on her all along, realizes that he’s gone too far, and he finally agrees to her marriage to the man she loves. That’s the story.

A.H. That’s just the trouble. There is no story!

F.T. I see that you’re not very much interested in talking about Champagne. could you just answer one question: Was the film an assignment from the company or was it your own idea?

A.H. What happened, I think, is that someone said, “Let’s do a picture with the title Champagne,” and I thought of beginning it in a certain way, which was rather old-fashioned and a little like that very old picture of Griffith’s, Way Down East. The story of a young girl going to the big city.

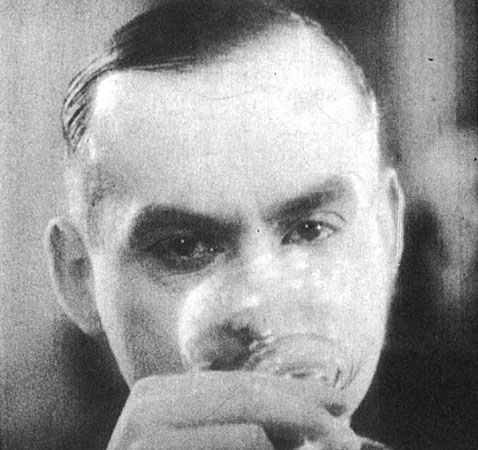

On the set of Champagne. From right to left: E. A. Dupont (director of Variety), Monty Banks. John Maxwell (producer), Prince Aage, J. Thorpe, Betty Balfour, J. Grossman (studio manager) and Hitchcock.

My idea was to show a girl, working in Reims, whose job is to nail down the crates of champagne. And always, the champagne is put on the train. She never drinks any—just looks at it. But eventually she would go to the city herself, and she would follow the route of the champagne—the night clubs, the parties. And naturally she would get to drink some. In the end, thoroughly disillusioned, she would return to her old job at Reims, by then hating champagne. I dropped the whole idea—probably because of the moralizing aspect.

F.T. There were lots of sight gags in the version I saw.

A.H. The nicest one, I think, was the drunkard who’s staggering down the ship’s corridor and swaying from side to side when the ship is steady, but when it is rolling like hell and everyone else is having a hard time trying to keep his balance, he walks in a perfectly straight line.

F.T. I also remember the dish that starts out from the kitchen looking very messy, with everybody putting his filthy fingers in it. As it is carried to the dining room, refining touches are added en route. And what has started out as a revolting-looking mess in the kitchen becomes very elegant and grand by the time it reaches the customer. The picture was full of these humorous inventions.

F.T. The Manxman, in contrast with Champagne, is a very serious picture.III

A.H. The only point of interest about that movie is that it was my last silent one.

F.T. Another point of interest is that it suggested the talkies. I remember that at one moment the heroine says, “I’m expecting a baby.” She articulates the phrase so clearly that one can read her lips. In fact, you dispensed with a title.

A.H. That’s true, but it was a very banal picture.

F.T. True, it was fairly humorless, yet, the story, in some respects, bears a resemblance to Under Capricorn or I Confess. One feels you really believed in this film.

A.H. It’s not a matter of conviction, but the picture was the adaptation of a very well-known book by Sir Hall Caine. The novel had quite a reputation and it belonged to a tradition. We had to respect that reputation and that tradition. It was not a Hitchcock movie, whereas Blackmail . . .

F.T. Before going on to Blackmail, which is your first talking picture, I would like a few words on silent films, in general.

A.H. Well, the silent pictures were the purest form of cinema; the only thing they lacked was the sound of people talking and the noises. But this slight imperfection did not warrant the major changes that sound brought in. In other words, since all that was missing was simply natural sound, there was no need to go to the other extreme and completely abandon the technique of the pure motion picture, the way they did when sound came in.

F.T. I agree. In the final era of silent movies, the great film-makers—in fact, almost the whole of production—had reached something near perfection. The introduction of sound, in a way, jeopardized that perfection. I mean that this was precisely the time when the high screen standards of so many brilliant directors showed up the woeful inadequacy of the others, and the lesser talents were gradually being eliminated from the field. In this sense one might say that mediocrity came back into its own with the advent of sound.

A.H. I agree absolutely. In my opinion, that’s true even today. In many of the films now being made, there is very little cinema: they are mostly what I call “photographs of people talking.” When we tell a story in cinema, we should resort to dialogue only when it’s impossible to do otherwise. I always try first to tell a story in the cinematic way, through a succession of shots and bits of film in between.

It seems unfortunate that with the arrival of sound the motion picture, overnight, assumed a theatrical form. The mobility of the camera doesn’t alter this fact. Even though the camera may move along the sidewalk, it’s still theater. One result of this is the loss of cinematic style, and another is the loss of fantasy.

In writing a screenplay, it is essential to separate clearly the dialogue from the visual elements and, whenever possible, to rely more on the visual than on the dialogue. Whichever way you choose to stage the action, your main concern is to hold the audience’s fullest attention. Summing it up, one might say that the screen rectangle must be charged with emotion.

I. Alfred Hitchcock can also be recognized in a later sequence of the picture, in which, wearing a cap and leaning against a railing, he is one of the bystanders looking on as Ivor Novello is captured by the police.

II. After becoming champion, the Australian Falls in love with the heroine and presents her with a serpentine bracelet. As they embrace, the girl moves the bracelet high up on her arm, above the elbow. When her fiancé, Jack, arrives on the scene, the girl hastily drops the bracelet down to her wrist, concealing it with her other hand To embarrass her in front of Jack, the Australian deliberately holds out his hand to say good-by. The girl, intent on concealing the bracelet, fails to respond, and Jack takes this seeming rejection as evidence of her loyalty to him.

In another scene, while the girl and Jack are together near a river, she accidentally drops the bracelet into the water. After retrieving it. Jack asks for an explanation. The Australian, she explains, gave it to her because he didn’t want to spend the money won in a fight against his rival on himself. "So, it’s really mine." Jack says, taking the bracelet from her and winding it around her finger, like a wedding band.

In this, and several other ways, the sinuous bracelet weaves its wav through the theme and winds up being twisted around itself, like a snake. The film’s title, The Ring, may be taken in its dual sense, referring both to a boxing arena and a wedding band.

III. The action takes place on the Isle of Man. The plot centers around three characters: Peter, a poor fisherman, and Philip, a lawyer, are both in love with Kate. When Peter’s proposal of marriage is rejected by the girl’s father on the grounds that he can’t support her, he leaves the island, telling Kate he will return for her after he has made a fortune. When they hear a report that Peter has died, Kate discovers that Philip has been in love with her and she admits her feelings for him. But one day Peter unexpectedly turns up again, and Kate, faithful to her promise, marries him. When she gives birth to Philip’s child, she realizes she cannot continue living with Peter and asks Philip to run away with her. When he refuses, she attempts suicide. Since suicide is considered a crime on the island, she is summoned before a tribunal, where she and Philip are forced into a public confession. The story winds up with Kate and Philip leaving the isle with their child.