Number Seventeen: the chase sequence.

Though these were facilities that I had never enjoyed myself, Van Druten turned the proposition down. I was never able to figure out why. Meanwhile, I was also considering a story written by Countess Russell. The story was about a princess who steals away from the court and has two weeks of fun and adventure with a commoner. Does that sound familiar to you?

F.T. Of course. It’s Roman Holiday.

A.H. Well, we never made it. Then I embarked on a Bulldog Drummond story, with two writers. It was a very good script, and the producer, John Maxwell . . .

F.T. Maxwell is the man who had produced all of your movies since The Ring, in 1927?

A.H. Yes. Maxwell sent me a letter saying: “It’s a brilliant scenario, a tour de force, but I don’t want to produce it.” I have a hunch that a critic whom I had brought into the studio and recommended as story editor was intriguing against me and the picture. So it was never made. And that was the end of my period with British International Pictures.

F.T. Which brings us to 1933. Things were not going too well for you at this time. I can’t believe Waltzes from Vienna was your own choice.

A.H. It was a musical without music, made very cheaply. It had no relation to my usual work. In fact, at this time my reputation wasn’t very good, but luckily I was unaware of this.

Nothing to do with conceit; it was merely an inner conviction that I was a film-maker. I don’t ever remember saying to myself, “You’re finished; your career is at its lowest ebb.” And yet outwardly, to other people, I believe it was.

Rich and Strange had been a disappointment, and Number Seventeen reflected a careless approach to my work. There was no careful analysis of what I was doing. Since those days I’ve learned to be very self-critical, to step back and take a second look. And never to embark on a project unless there’s an inner feeling of comfort about it, a conviction that something good will come of it. It’s as if you were about to put up a building. You have to see the steel structure first. I’m not talking about the story structure, but about the concept of the film as a whole. If the basic concept is solid, things will work out. What happens to the film, of course, becomes a matter of degree, but there should be no question that the concept is a sound one. My mistake with Rich and Strange was my failure to make sure that the two leading players would be attractive to the critics and audience alike. With a story that good, I should not have allowed indifferent casting.

Sir Gerald du Maurier in Lord Cambers Ladies.

While we were shooting Waltzes from Vienna, at this low ebb of my career, Michael Balcon came to see me working at the studio. He had given me my first chance to become a director. He said: “What are you doing after this picture?” I said, “I have a script that was written some time ago; it’s in a drawer, somewhere.” I brought in the scenario; he liked it and offered to buy it. So I went to my former producer, John Maxwell, and bought it from him for two hundred and fifty pounds. I sold it to the new Gaumont-British company, which was headed by Balcon, for five hundred pounds. But I was so ashamed of the hundred per cent profit that I had the sculptor Jacob Epstein do a bust of Balcon with the money. And I presented Balcon with Epstein’s bust of him.

F.T. And that was the scenario of The Man Who Knew Too Much?II

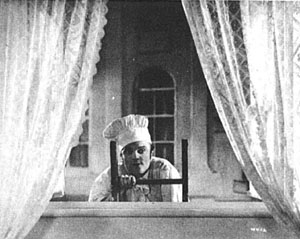

The cook as voyeur in Waltzes from Vienna (1933).

A.H. That’s right. It was based on an original Bulldog Drummond story by “Sapper” and adapted by Charles Bennett, with a newspaper columnist, D. B. Wyndham-Lewis, doing the dialogue. So actually, it’s to the credit of Michael Balcon that he originally started me as a director and later gave me a second chance. Of course, he was always very possessive of me, and that’s why he was very angry, later on, when I left for Hollywood. But before talking about The Man Who Knew Too Much, I want to make a point. And that is that whatever happens in the course of your career, your talent is always there. To all appearances, I seemed to have gone into a creative decline in 1933 when I made Waltzes from Vienna, which was very bad. And yet the talent must have been there all along since I had already conceived the project for The Man Who Knew Too Much, the picture that re-established my creative prestige.

Anyway, to get back to 1934. First, there’s a thoroughly sobering self-examination. And now, I’m ready to go to work on The Man Who Knew Too Much.

I. The story is too long to be properly summed up. It takes place during the Dublin uprising and tells about the eccentric goings on of an impoverished family that’s about to inherit some money. The prospect of the inheritance unbalances the head of the family, the self-appointed “Captain” Boyle (the Paycock), whereas his plump wife, Juno, is solid and down to earth. In the end, when it turns out there is no inheritance, the family is disgraced, with the daughter expecting an illegitimate child and the son shot as an informer.

II. In accordance with the chronological arrangement of these conversations, the above-mentioned picture is the original British version of The Man Who Knew Too Much, made in 1954. Twenty-two years later, in 1956, Alfred Hitchcock directed a remake of the picture, co-starring James Stewart and Doris Day.