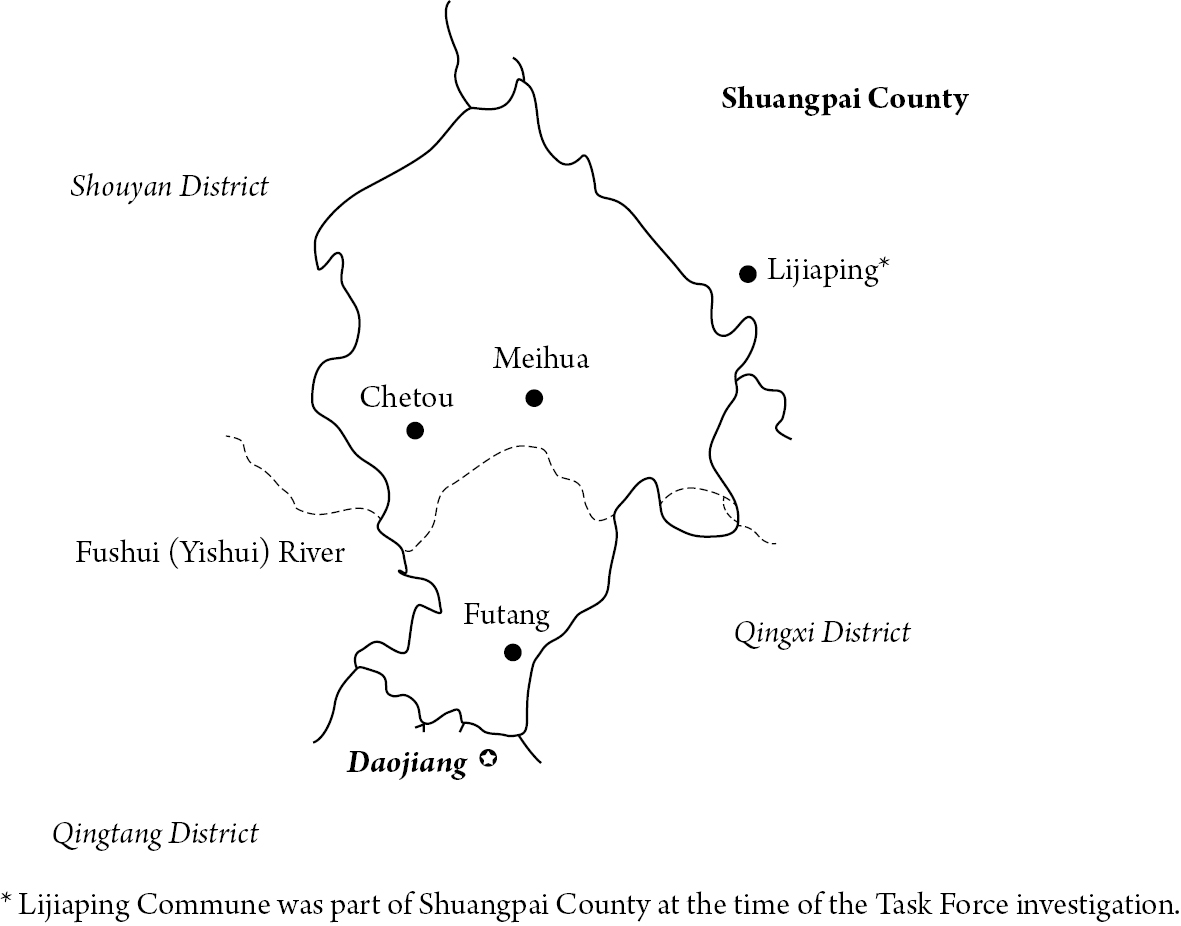

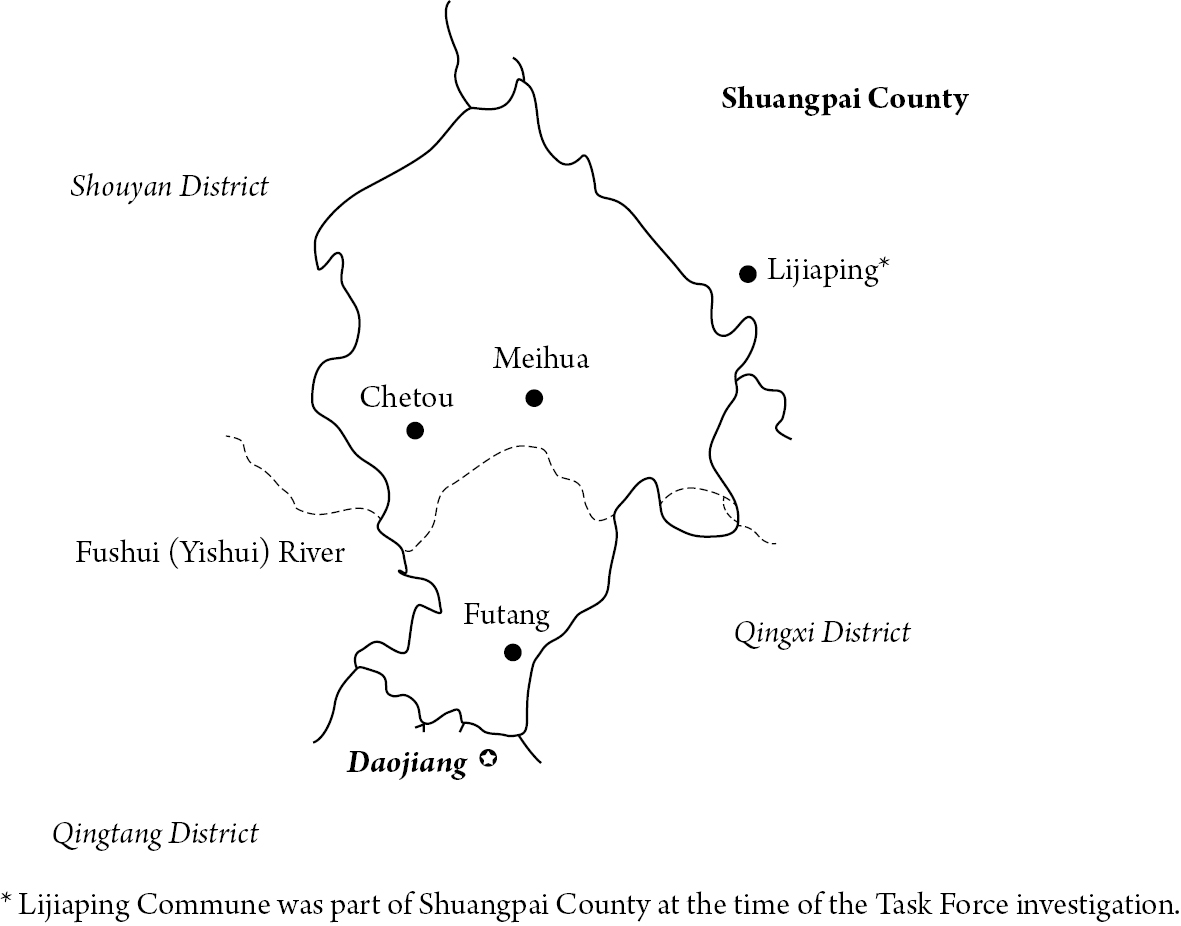

Map 4 Communes of Chetou (Meihua) District

When during the August 21 Yingjiang reporting meeting, Chetou District People’s Armed Forces Department (PAFD) commander Zhong Changyou reported to Military Subdistrict deputy commander Zhao Erchang and the others on the situation of class enemies staging a revolt, seizing the PAFD’s weapons and hiding in the hills, what was he referring to? He’d made no mention of this matter two days earlier, when the Yingjiang Frontline Command Post was established, so how had he come across such a major piece of intelligence overnight?

After the inaugural meeting to establish the Yingjiang Frontline Command Post, Zhong Changyou found time to hurry back to Chetou District on August 19. For all his insistence on focusing on the “big picture,” Zhong was head of his district’s seize-and-push group and felt compelled to monitor what was happening in the district.

(I previously noted that the administrative reorganization of Daoxian after the Cultural Revolution led to Chetou District being renamed Meihua District1 and losing Lijiaping Commune to Shuangpai County while retaining Meihua, Chetou, and Futang Communes under its jurisdiction (See Map 4). As in other cases, this somewhat muddied the waters when the Task Force subsequently tried to establish cause and effect in the Daoxian massacre.)

Yingjiang was only around 7 kilometers from Chetou, and traveling this route was a routine matter for a veteran grassroots cadre such as Zhong Changyou. Crossing the Lianxi and Fushui Rivers slowed things down, however, so Zhong didn’t reach Chetou until midafternoon. By then, public-security deputy He Tian and others had been waiting for him in the district office for quite some time. He Tian quickly called Zhong Changyou into his office and grilled him on how the Cultural Revolution was progressing in the county, and about the establishment of the Frontline Command Post in Yingjiang. After answering He Tian’s questions as concisely as possible, Zhong Changyou said gravely, “The current situation is very tense. It’s by no means certain whether the Red Alliance or the Revolutionary Alliance will prevail in the end, and black elements are preparing to make trouble all over the county. According to Zheng Youzhi, the Liao clan’s landlords and rich peasants staged a rebellion in their district, but fortunately the poor and lower-middle peasants quickly discovered it and suppressed six of them.”

Map 4 Communes of Chetou (Meihua) District

He Tian responded sympathetically, “We hear a dozen or so black elements are active in the hills of Xiganqiao.”

When Zhong Changyou heard this, he became very anxious and said, “He Tian, you need to send people right away to look into this. If it turns out to be true, we have to arrest them immediately. For now we’ll organize a militia to keep an eye on the black elements. If any cause trouble or try to settle old scores, the masses need to arrest them and kill the ones they think should be killed. We can’t allow any lingering threat.”

He Tian said, “Don’t worry, Commander Zhong, we’re on the case.”

After speaking with He Tian, Zhong Changyou arranged for the next stage of operations in the district and then hurried back to Yingjiang. Zheng Youzhi had telephoned to chase Zhong back to Yingjiang as soon as he had arrived in Chetou; with the Frontline Command Post just established, there was much to do, and Zhong couldn’t be spared.

As soon as Zhong Changyou set off, an “enemy situation” occurred in Meihua Commune. While the Shewan production brigade militia was carrying out routine checks on August 20, it came across a man around 50 years old, whose arms bore bruises and scars from being tied and beaten. When detained and interrogated, the man revealed that this name was Tang Linxian, and that he was a pre-Liberation counterrevolutionary from Lijiaping Commune’s Lijiaping brigade. Although from a middle peasant family, he had served as a policeman under the Kuomintang regime, which meant he was no good. It turned out that on August 9, Tang Linxian had gotten into a dispute with his nephew’s wife over some trivial matter. Tang felt that as a member of the older generation, he should get his way, but the nephew’s wife saw things differently, saying that since he was a class enemy and she was a poor peasant, he should submit to her supervision and control. The production brigade had decided in favor of the woman and tied up Tang Linxian in preparation for puncturing the arrogance of the class enemy. Tang Linxian had managed to loosen the ropes and escape, but lacking a certificate from his production brigade, he could only roam around and support himself through odd jobs until he was finally captured on August 20.

The Lijiaping brigade was notified to fetch Tang Linxian, and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) secretary Wang Huanliang rushed off to Shewan with public-security deputy Wang Tianqing and core militia member Tang Liqiang, who happened to be Tang Linxian’s nephew. Because Tang Linxian had “received counterrevolutionary training” as a puppet police officer, Wang Huangliang and the others were on their guard, and upon reaching Shewan, they hogtied Tang Linxian before taking him back to Lijiaping. Wang Huanliang later said, “We didn’t intend to kill Tang Linxian, but only to take him back to the production brigade and request instructions from the commune on how to deal with him.” However, on the way back, Tang Linxian misbehaved, pulling various stunts and dragging his feet instead of following along obediently, sometimes acting pitiful and claiming to have done nothing wrong and begging for mercy and other times complaining that the rope was too tight and demanding that it be loosened. His nephew Tang Liqiang finally lost his temper, snatched the gun Wang Tianqing was carrying, and aimed it at Tang Linxian. It went off, and Tang Linxian dropped to the ground. Wang Huanliang examined him and found he was dead.

At that moment, the three men panicked. Although by then some black elements and offspring had been killed during struggle sessions or had killed themselves, this was the first time someone had been shot in broad daylight, and Daoxian’s “killing wind” hadn’t yet reached the point where someone could be killed without worrying about the consequences. Wang Tianqing, the smartest of the group, told Tang Liqiang, “We’ll say your uncle was shot while trying to grab the gun.” Everyone thought this was a great idea, and that’s what they reported to He Tian after hurrying back to the district. He Tian said, “It’s intolerable for a class enemy to seize arms from the militia! He deserved to be killed.”

This is the closest version to the truth regarding what later circulated throughout the county as “class enemies snatching militia weapons in District 2 to mount an insurrection.” During the August 21 Yingjiang reporting meeting, Zhong Changyou and others passed on this rumor to Lingling Military Subdistrict deputy commander Zhou Erchang and the 47th Army as an example of how black elements were mounting insurrections.

At one point we asked a Task Force comrade, “It seems that this kind of counterrevolutionary gun-snatching case should have been a major incident at that time. The scene of the crime was less than an hour from the district office, even by sedan chair, so why didn’t He Tian go there and investigate the matter himself? Wouldn’t an experienced politics and law cadre like him think there was something fishy about the claim that a hogtied old fellow in his 50s could snatch a gun from three armed militiamen?”

The Task Force comrade said, “You can’t view the matter from our current perspective. As soon as we went there to carry out our inquiries, people talked about Tang Linxian being shot in a gun-snatching attempt, and we immediately knew it was a lie. But at that time, if there were no cases of class enemies mounting an insurrection, they had to be invented. He Tian had come to take a nap, and when someone provided him with a pillow, he naturally put his head down and snored away.”

An old Daoxian cadre said, “Class struggle was easy because it could be fabricated, but also hard because it must be fabricated.”

Back in Yingjiang, Zhong Changyou continued to obsess over what was happening in his district, and on the afternoon of August 20, he telephoned Chetou to ask how things were going. He Tian wasn’t there, but the head of the district women’s association, Zhang Gui’e, answered the phone, and she told Zhong of the Tang Linxian incident. That night, He Tian himself telephoned Yingjiang to report the matter to Zhong Changyou. Zhong said, “The black element brought this upon himself. It’s a good thing, not a bad thing. Quickly pull together the information, and I’ll report it to Deputy Commander Zhao and the 47th Army comrade tomorrow.” He added, “Have every production brigade carry out inspections to see if there are more of these miscreants around. Every brigade should kill two of the worst ones.”

A Task Force comrade who investigated this case observed that Zhong Changyou had always been on good terms with He Tian, but once the Task Force began its work, the two of them had a falling out. He Tian said, “Zhong Changyou is always accusing me of killing people and still refuses to admit his errors.” Zhong Changyou said, “He was the one who pushed for killing people, and now he’s trying to put the responsibility on me. He’s such a liar.” Between the two of them, they turned a family quarrel into a counterrevolutionary incident.

Tan Linxian was the first victim of the Cultural Revolution’s “killing wind” in Chetou (Meihua) District. Influenced by this incident, Chetou Commune’s Shewan brigade obtained commune-level permission to kill a 50-year-old landlord element named Wu Zhicheng on August 21.

On August 22, Chetou District called a Cultural Revolution Committee (CRC) meeting presided over by district CCP secretary Yang Jifu to discuss and implement the spirit of a telephone conference by the county seize-and-push leading group. During this meeting the “enemy situation” was greatly exaggerated.

The next day (August 23) at noon, a mobilization meeting was called for the district’s administrative cadres, with district public-security deputy He Tian presiding and a speech by Wu Ronggao, the district head and deputy CCP secretary. In his speech, Wu played up various bogus reports of enemy activity and encouraged killings: “In Lijiaping, a counterrevolutionary seized a weapon to mount an insurrection but was suppressed by the poor and lower-middle peasants. This shows that in our district the masses have truly risen up and realize they’re the masters of their own affairs. If we don’t kill the most-heinous black elements, they’ll turn around and kill us. From now on, the poor and lower-middle peasants are the ones who decide whether to kill the most-heinous criminals.”

Just before the meeting adjourned, Wu Ronggao stood once more with a cryptic smile on his face and said, “Comrades, I have a suggestion: after lunch, let’s all go have a look at the Meihua production brigade.”

The formerly hushed meeting buzzed with excitement. Those familiar with Wu Ronggao’s temperament and work style knew there would be something worth seeing at the Meihua brigade. Someone impatiently asked a Meihua Commune cadre sitting next to him, “What new moves is your commune going to show us?” The Meihua Commune cadre smirked and said, “Just come and see, then you’ll understand everything.”

It turned out that the day before the district mobilization meeting, Meihua Commune had held a “four chiefs” meeting to arrange some killings. Commune CCP secretary Jiang Yixin had presided over the meeting, with commune secretary Liao Longguo delivering the main speech. After the meeting adjourned, Liao Longguo had the Meihua brigade cadres stay behind and instructed them to hold a grand mass rally on the 23rd, during which a 50-year-old landlord element named He Wencheng would be killed to mobilize the masses and intimidate the enemy. Secretary Liao repeatedly told them: “There will be observers at the meeting, so don’t do anything that will make the commune lose face.”

After the rally, He Wencheng was taken to an abandoned limekiln, where public-security head He Xianfu asked him, “Do you want to live? If so, hand over your movable property, and your life will be spared.” As someone who had experienced Land Reform, He Wencheng was familiar with this policy and repeatedly expressed willingness to pay for his life. He didn’t realize that after paying the 180 yuan2 he would still be killed. When the Task Force later carried out its inquiries, He Xianfu would admit to taking only 80 yuan, and what happened to the other 100 yuan was never determined. He Xianfu told the Task Force that after taking the payment, “We originally wanted to spare his life, but people had come to observe and we had to kill someone, so we couldn’t come up with any other idea but to kill him.”

After observing the killing at the Meihua brigade, Lijiaping’s cadres rushed back and the next day held their own commune cadre meeting to transmit the spirit of the August 23 district meeting, report on what had happened at the Meihua brigade, and arrange for their own killing campaign. In the five days following the meeting, more than 170 people were killed in Chetou District (not including those killed in Lijiaping Commune3).

On August 25, He Tian left Chetou to attend the Yingjiang Political and Legal Work Conference and then communicated the gist of the conference at another meeting for administrative cadres in Chetou District on August 29, and Liao Longguo read out the Lingling Military Subdistrict’s “Cable on the Social Situation” transmitted by the 47th Army. Giving the meeting’s keynote speech, He Tian spoke of the previous killings by saying, “The poor and lower-middle peasants rose up and killed some troublemaking black elements who had committed heinous crimes. This was an excellent revolutionary act! We should vigorously support it. However, some errors arose and killings became random, and some who shouldn’t have been killed were killed while others who should have been killed were not. We mustn’t randomly kill people, especially the heads of reactionary organizations. We should spare them, not because they don’t deserve to die, but because through them we can continue to dig deeper and round up the entire reactionary organization behind them. We can kill a few of the most heinous criminals if the masses insist, but there should be no indiscriminate killing.”

He Tian was in fact repeating comments that Zheng Youzhi and others made at the Yingjiang Political and Legal Work Conference. After the August 29 meeting, Chetou District experienced a second upsurge in killings just like the rest of the county.

I’ll sketch out the killings in Meihua and Chetou Communes, but not in Lijiaping Commune, which came under the jurisdiction of investigations in Shuangpai County.

I mentioned earlier that Meihua Commune had already held a killing-mobilization meeting before the district mobilization meeting was held, and that after its meeting, Meihua had assigned the Meihua brigade to serve as an “advanced model.” Even so, the Meihua brigade recorded only seven deaths, with two more killings on August 26 and three killings and a suicide on August 29.

I consider the Meihua brigade emblematic, in that (1) it kept in close step with the upper-level leaders—when the upper level held a meeting, it carried out a round of killings in close coordination, and (2) the killings were few but carried out with great fanfare. In each case, a mass rally was called to denounce the victims, during which the poor-peasant association (PPA) represented the brigade’s peasant supreme court in proclaiming the “nature of the offense,” and then the victim was escorted ceremoniously to the execution ground. Black elements and offspring who weren’t killed were brought to the execution ground for “reeducation.”

The executions of the last three people on August 29 can serve as an example. After the district held its meeting to implement the spirit of the Yingjiang Political and Legal Work Conference, the Meihua brigade decided on another round of killings, saying, “We might not have another good chance in the future.” They settled on a rich peasant, Mo Desheng, and a poor peasant, Wen Shangyi, along with his son, Wen Shoufu.

Killing Mo Desheng was understandable, since he was a class enemy, but why kill the poor peasants Wen Shangyi and his son? Inquiries determined that the cadre Wu Dexue took the opportunity to avenge himself against Wen Shangyi, who had criticized him back during the Socialist Education movement. He Guoqing, He Antao, and others went along with Wu, and they agreed to kill Wen’s son, Wen Shoufu, at the same time to prevent future trouble. Aware that complications could develop over killing poor peasants, He Antao used his status as CRC chairman to request instructions from commune secretary Liao Longguo. Liao said, “Not all poor peasants are guaranteed Reds. If they need to be killed, then kill them.”

When Wen Shangyi and his son were killed, Wu Dexue, He Guoqing, and the others bound them up with the rich peasant Mo Desheng and then blew them up with dynamite, a process known as “flying the homemade airplane.” Because the amount of explosive used was inadequate, or for some other reason, Wen Shangyi and Mo Desheng were blown to smithereens, but Wen Shoufu only had his buttocks blasted off, and he writhed on the ground in agony. Wu Dexue ran over, used his fingers to gouge out Wen Shoufu’s eyes, and stuffed them in his mouth. According to local lore, if Wen Shoufu went to hell blind, he would be unable to find his way back to the living world to wreak revenge. When Wen Shoufu continued to breathe, Wu Dexue cut his throat with a saber. After killing the father and son, Wu Dexue went to the Wens’ home and pointed his dripping saber at Wen Shangyi’s sobbing wife, saying, “Your son died on this knife. If you lick the blood off, I’ll let the matter rest. Otherwise, I’ll kill you, too.” After forcing Wen Shoufu’s mother to lick his blood off the saber, Wu Dexue took the matter no further.

When an elderly woman from the landlord class, Wu Nanzhu, witnessed the horrific deaths of Mo Desheng and the Wens, she was so terrified that she hanged herself that very night.

There are plenty of stories about the killing of landlords and rich peasants, so at this point I will just mention the killing of a poor peasant in the Xiepidu production brigade. Among the 4,500 people killed during the Daoxian massacre, more than 350 were poor or lower-middle peasants, and I need to explain how such killings came about.

After the killing-mobilization meeting at Meihua Commune on August 22, the commune’s top cadres went down to the villages to encourage and supervise killings. Commune CCP secretary Jiang Yixin went to the Chiyuan brigade, while deputy CCP secretary Wang Guoxiang and commune director He Changbao went to the Tangjiashan brigade. The commune’s Youth League secretary, Li Rentao, went to the Xiepidu brigade to guide operations because he had been assigned to this brigade during the earlier Socialist Education movement.

On August 24, Li Rentao presided over an enlarged cadre meeting at the Xiepidu brigade to implement the spirit of the August 22 commune-level meeting. Li Rentao talked about the brigade’s production problems and the situation of class struggle throughout the county, and then he asked, “Does our brigade have one or two troublemakers we can kill?” Core militia members Li Junsheng and Li Cisheng (a blacksmith) stood up and replied, “Of course we do! He Zhonggong is one.” But none of the representatives of the masses spoke up to endorse this killing as in other localities. There were three reasons for this: one was that He Zhonggong was a poor peasant; second, the Li brothers had a grudge against He Zhonggong; and third, the Li brothers were themselves highly problematic, involved in pilfering and messy sexual relationships. In particular, Li Cisheng had spent half a year in “reform through labor” for stealing, and although a steadfast revolutionary, he was a person of poor character and reputation.

After the meeting adjourned, Li Rentao had the brigade’s main cadres stay behind for further discussion. Brigade CCP secretary He Rushun said, “He Zhonggong really is an incorrigible troublemaker, and it would be acceptable to kill him.” But Li Rentao withheld his approval: “We have to be discreet about killing a poor or lower-middle peasant. Detain him first and investigate the matter further before we decide.”

Treating this as a full-fledged delegation of authority, Li Junsheng and Li Cisheng immediately tied He Zhonggong up and locked him in the brigade storehouse. That night, He managed to escape and took his son, He Ruchang, with him. Perhaps he worried that if he fled on his own, the brigade would call his son to account, but he didn’t consider how dangerous it was to take his son along. The entire county had militia manning a vast network of checkpoints, and the father and son were nabbed at Dongmen Commune within two days. After the Xiepidu brigade sent someone to bring them back, father and son were tied to a column in the brigade’s ancestral hall. Someone asked, “How should we deal with them?” CCP secretary He Rushun sighed and said, “Now we have no choice but to kill them.”

It had to be done discreetly, however, so Li Junsheng was sent to the commune to request instructions from Li Rentao. Li Rentao replied, “Strike while the iron is hot and get rid of them.”

Li Junsheng trotted back to the production brigade and said, “Secretary Li has given us permission to quickly kill this fellow and his whelp.”

He Rushun said, “Go to it, then.”

When the time came for the father and son to be killed on August 30, Li Rentao came to personally oversee it. Because rifle bullets were precious, the two were shot with fowling pieces, and the first round of shots wasn’t fatal. Stamping his foot anxiously, Li Rentao told He Rushun to get it over with. He Rushun was dressed in a white robe; afraid of soiling it, he fired from farther away, and when this shot was likewise ineffectual, Li Rentao berated him as useless. A core militiaman finally hurried over and finished the men off with his blunderbuss.

After He Zhonggong and his son were killed, an elderly woman of the landlord class, Wu Chengyuan, hanged herself on September 2.

The greatest number of killings at Meihua Commune occurred in the Dongfeng brigade. This was one of the notable cases highlighted by the Task Force, which observed that the killings were carried out with a bugle call. This production brigade, which included the natural villages of Xitian, Zhenggu, and Huangtudong, recorded 28 deaths during the “killing wind,” including three suicides.

After presiding over the commune’s killing mobilization meeting on August 22, commune CCP secretary Jiang Yixin went straight to the Dongfeng brigade on August 23 to oversee operations. The brigade immediately held a cadre meeting and came up with a list of names. The first batch of five people was killed on August 24. After a meeting of administrative cadres was called on August 29 to implement the spirit of the Yingjiang Political and Legal Work Conference, the brigade quickly killed another batch of 16 people on September 1, with piecemeal killings after that. This production brigade had a militia platoon leader named He Tiexian who killed 11 people single-handedly and raped the wives and daughters of many of his victims.

So what was the incident in which people were killed by bugle call?

A grassroots cadre from the Dongfeng brigade said, “When we weren’t allowed to discuss killings, He Guosheng proposed using a bugle as a signal for all three villages to move at once. That idiot always wanted everyone to remember that he’d served as a bugler in the army, but all it did was make our brigade notorious once the Task Force brought it to light, even though Zhangwufang killed a lot more people.”4 He added, “The fact is that the people would have been killed whether or not the bugle was blown, so what does it matter?”

Words leapt to my throat, but I held them back, knowing that the only way to continue our reporting was to listen more and say less.

After the Dongfeng brigade killed 16 black elements and offspring on September 1, the upper-level prohibition against random killing reached the brigade and was transmitted during a cadre meeting on the morning of September 2. That evening, when a brigade member named He Ruobei returned from sideline work in the county seat,5 a middle peasant named He Dingxin and his son He Ruoying came to chat with him. It was normal for villagers to want to hear what was going on in town, especially when there had just been an earthshaking battle between the Red Alliance and Revolutionary Alliance in Daojiang on August 30. There were rumors that class enemies had gained the upper hand and seized arms and that they had set up a base camp in the No. 2 High School, where they had hung a portrait of Chiang Kai-shek and distributed reactionary leaflets. He Dingxin and his son were experienced and knowledgeable men, and finding all this incredible, they came to ask He Ruobei what was really going on.

He Ruobei’s neighbor noticed this and suspected that He Ruobei had come back from the Revolutionary Alliance’s bandit lair to establish ties in the village. The report quickly reached brigade militia commander He Ziliang, who immediately summoned a dozen or so militiamen to arrest He Dingxin and He Ruoying. Why didn’t they arrest He Ruobei? Supposedly, since He Ruobei had come back to the production team to hand over the proceeds of his sideline occupation, He Dingxin and He Ruoying had an additional motive for going to ask him about the “bandit’s lair,” showing how ruthlessly ambitious and venomous they were.

Since the cadre meeting prohibiting further killings had just been held, any demands for the killing of “heinous” criminals required compiling and submitting a file to the commune for permission. This posed no real difficulty to He Ziliang and the others, however; acting in the name of the brigade CCP branch, they quickly put together a file accusing He Dingxin of colluding with bandits, supplemented with a file on a “rich-peasant element who had slipped through the net” as a middle peasant, He Xisheng, and submitted them to the commune.6 The commune agreed to the killings.

On the morning of September 5, He Ziliang and others called a mass rally of commune members to read out the crimes of He Dingxin and He Xisheng. After the rally, he personally led more than 20 militiamen who hogtied He Dingxin and He Xisheng and took them to Shizi Mountain to be executed. He Dingxin’s son He Ruoying was also bound and taken along to witness the execution. He Xisheng was killed first, but when it was time to kill He Dingxin, He Ziliang halted the proceedings and asked He Dingxin, “Tell me, would you still dare to cut down my family’s camphor tree?”

It turned out that in 1950, when He Dingxin was serving as a district representative, he had cut down a camphor tree near Zhongren Pond. His family and He Ziliang’s had fought repeatedly over who owned the tree, and He Dingxin had used his status to take possession of it by force. The two families pursued the dispute to the township and district levels, and eventually He Dingxin won the lawsuit. The two families had nursed a mutual grudge ever since. He Ziliang said, “You had the big mouth back then, and we couldn’t out-talk you. But that tree belonged to my family—my granddad planted it with his own hands.”

“What camphor tree are you talking about?” It had happened so long ago that He Dingxin couldn’t recall it right away.

“What camphor tree? You may not remember, but I do, and when you see the King of Hell, you’ll have lots of time to think about it.”

After killing He Dingxin, He Ziliang worried that He Dingxin’s son might try to avenge his father’s death, so he claimed to have received a message from the commune saying that He Ruoying had joined a reactionary organization and had three militiamen bring He Ruoying in to be interrogated. But He Ruoying denied involvement in any counterrevolutionary organization: “You can go and investigate, and if you find out I was a member of a counterrevolutionary organization, you can throw me in jail or execute me as you like.”

He Ziliang pounded on the table and yelled, “Since you won’t cooperate, I’m tying you up.”

Two militiamen went over and hogtied He Ruoying. Seeing how things were going, He Ruoying pleaded with He Ziliang for mercy: “Brother Ziliang, just give me some idea of what I’ve done wrong, and I’ll think it through and confess everything.”

He Ziliang said, “So you’ve never done anything wrong? Your old man cut down my family’s camphor tree.”

He Ruoying said, “That was my father’s business. I was just an ignorant boy at the time, so how can you blame me? My father’s dead, he’s paid for his crime… .”

Fed up, He Ziliang interrupted He Ruoying and said, “Enough. You’re wasting your breath.”

When they reached the edge of the Panjia limekiln, He Ziliang ordered the militiamen to shoot He Ruoying. The three militiamen were reluctant, having been told only to take He Ruoying to the commune. He Ziliang berated them: “Fuck your mothers, if you let him live he’ll overthrow us all!” He then grabbed a fowling piece and shot He Ruoying himself.

As he died, He Ruoying cried out, “He Ziliang, you dare to settle your private grudge in the name of public interest!”

He Ziliang laughed coldly: “So what if I did? You can bite my balls!” He ordered a militiaman to cut off He Ruoying’s head and took it back for public display.

Back during the Cultural Revolution, Chetou Commune had a formidable reputation. It was the model commune promoted by Hua Guofeng,7 then secretary of the Hunan provincial CCP committee secretariat, and was Daoxian’s famous “red flag”—during the 1958 Great Leap Forward, Hua Guofeng cited the high rice yield at the commune’s Shixiadu production brigade in his essay “Victory Lies with the People Who Leap Forward Holding Aloft the Red Flag,” which he submitted to the Hunan provincial CCP committee and CCP Central Committee. The most important highway linking Daoxian to the outside world—the Lingdao Highway running from Lengshuitan to Daoxian—traversed Chetou from north to south. When we went to Daoxian for our interviews and reporting, the first thing we saw through the drizzling rain was this stretch of lovely, fertile land.

Chetou Commune held its killing mobilization meeting on August 24. Commune deputy CCP secretary He Yongde, who at that time was in charge of the commune’s operations, communicated the spirit of the district’s August 23 meeting and arranged the commune’s killing campaign.

That afternoon, He Yongde personally went to the Sikongyan brigade to “direct operations.” The commune CCP committee’s organization and supervisory committee member Yang Zhengdong, commune director Zhu Qiaosheng, commune secretary Pan Jitong, and others also went to various other production brigades to encourage and oversee killings.

Compared with Meihua, this advanced commune seemed somewhat backward. In fact, Chetou began its killings earlier than Meihua, but with less fanfare. Apart from the killing of the old landlord Wu Zhicheng at the Shewan brigade on August 21, the Xiantian brigade killed another old landlord, Huang Yongdu, on August 22, a day earlier than Meihua’s killing of He Wencheng. On August 23, the Chetou brigade killed an old landlord named Zhou Jiapian at the instigation of commune deputy CCP secretary He Yongde.

Besides being the first brigade in Chetou Commune to start its killing, the Shewan brigade also killed the most people, a total of 15 (including three suicides). After the killing of Wu Zhicheng on August 21, a 59-year-old landlord element named Li Binqing was so terrified that he killed himself on August 23.

On August 24, the commune held its killing-mobilization meeting, and the Shewan brigade responded by killing four more people: two class enemy offspring (Wu Guangzheng, 20, and Li Qinshou, 23) and poor peasant Li Changrui, 44, and his son Li Zuwen, 17, a student at the Daoxian No. 1 High School.

The Task Force focused its investigations on four types of murder cases: those involving rape (including carrying out murder to seize someone’s wife), money, or revenge, and the killing of poor and lower-middle peasants. The Task Force’s inquiries established that the killing of Li Changrui and his son qualified for two of these categories: revenge and the killing of poor and lower-middle peasants. During the rural Socialist Education or “Four Cleans” campaign in 1962, Li Changrui had followed the instructions of the Four Cleans work team by criticizing public-security head Li Rongbao and the brigade’s then CCP secretary Li Yikuan, among others. This led to Li Rongbao and the others being investigated and forced to pay restitution. Li Rongbao carried a grudge against Li Changrui because of this, and the Cultural Revolution gave him and others a chance to revenge themselves with brigade CCP secretary Li Yikuan’s support. As a young student, Li Zuwen shouldn’t have been killed, but he went around the village flaunting the red armband of a Young Red Guard Militant, so he seemed the kind who would avenge his father’s death and consequently had to be killed as well.

There was a prevalence of this kind of revenge motive among the killings that occurred in Daoxian during the Cultural Revolution. While it can’t be said that every production brigade had such a case, every commune had more than a couple; I have material on more than 60 such cases.

After the Shewan brigade killed Li Changrui and the others on August 24, they killed a woman in her 60s from the landlord class, Pan Duanying, the next day. That evening, Li Xinqing, the son of rich peasant Li Ronghui, fled out of fear of being killed. Feeling that he had no way out, Li Ronghui hanged himself after his son fled. On the 26th, a 56-year-old woman from the rich-peasant class, Liu Luanying, committed suicide “to escape punishment.” After that, the production brigade killed a 19-year-old class enemy offspring on September 4, and four more offspring on September 10. The young man who had fled, Li Xinqing, was captured and killed on September 11.

I earlier mentioned the fame of the Shixiadu production brigade, and this is an appropriate time to speak of the killings there. This advanced production brigade, which created the myth of 5,000-kilo-per-mu rice yields, was far less “progressive” during the killing spree, recording only five deaths. The brigade had killed a 56-year-old woman from the landlord class, Pan Jinjiao, on August 26 to implement the spirit of the commune’s August 24 meeting, but when the August 29 district meeting required permission from the upper level for any future killings, Shixiadu’s cadres felt they had “missed out” and “appeared backward”; they said, “We killed too few in the previous round compared with other brigades. No matter what, we have to quickly kill a few more.” They then held a meeting and decided on four more people to kill.

Although they were obliged to submit files to the upper level, this was a simple matter for a reputed “advanced brigade,” and once they’d pulled the material together, brigade CCP secretary Wu Yaosheng personally delivered it to the commune to request instructions. Commune CCP secretary He Yongde was away at the time, so Wu took the file to commune secretary Pan Jitong. Pan said, “It’s not as easy to kill people as it was before. The higher authorities require prior authorization from the frontline command post. I suggest you drop it.”

When the Shixiadu cadres heard this, they felt they were in a spot. The killings weren’t absolutely necessary, but they’d already arrested the four targets, and the peasant supreme court had already handed down death sentences. If all this had to be taken back, the brigade’s cadres would lose credibility, and the black elements would become impossible to manage. When they pressed the matter, Pan Jitong reluctantly acquiesced: “Whatever you’ve decided, just do it. But when you kill them, do it along the river across from the Shangmo brigade, not over by Haitoumiao; blood all over the riverbank looks nasty, and the two households living at Haitoumiao will object.”

That evening, Wu Deying (46 years old), Wu Yourui (57), Wu Youqiu (52), and Wu Yongzheng (38) were led to the riverbank across from Futang Commune’s Shangmo brigade and were killed with explosives.