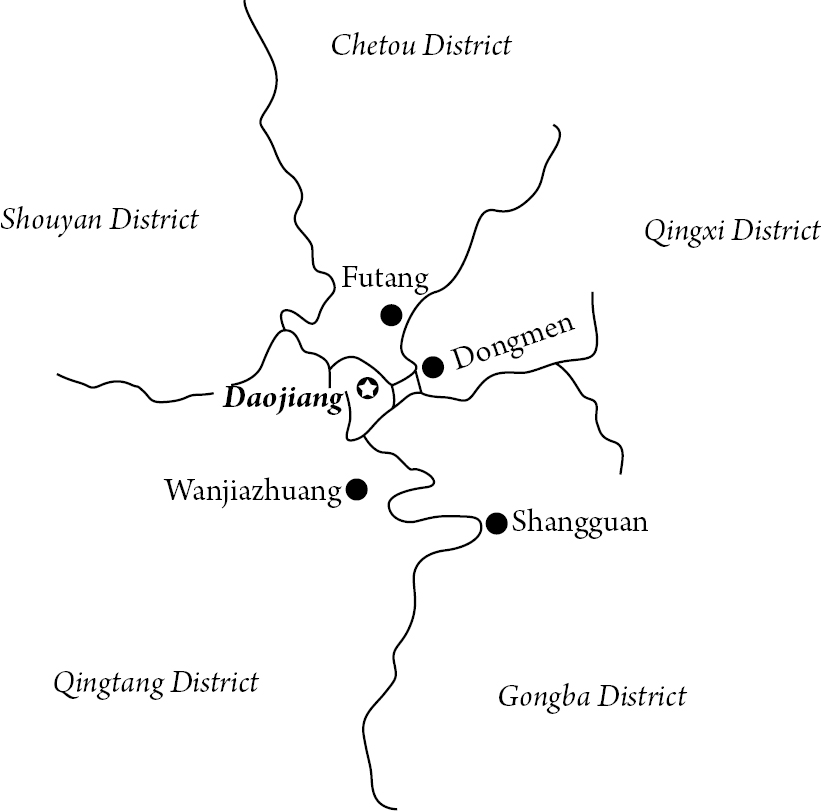

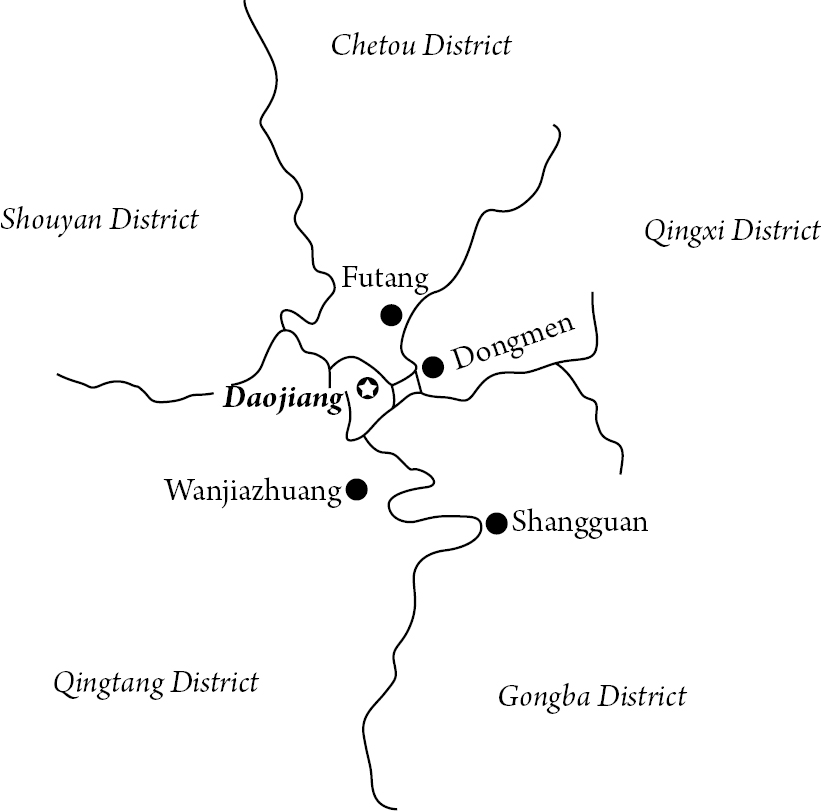

Map 5 Communes of the former Shangguan District

During Daoxian’s killing wind, killings were arranged by 18 of the county’s 37 communes. Among these, Shangguan Commune’s on-the-spot killing rally was the most distinctive.

Shangguan Commune was positioned on the southeastern border of the county seat of Daojiang, close to the Tuo River (as the Xiaoshui River was called where its upper reaches near Daojiang). Shangguan is now part of Gongba District, but at the time of the killings, it belonged to Shangguan District (Map 5), which no longer exists. The water and soil of Shangguan made it one of Daoxian’s most prosperous communes. The garlic chives of Daoxian were famous far and near, and the best were from Shangguan, where they grew tall and lush, their color crisp and their fragrance delicate; they were absolutely scrumptious.

On August 22, Shangguan Commune’s first on-the-spot killing rally was held at Baotajiao on the banks of the Tuo River.

Baotajiao lay less than 4 kilometers from Daojiang, and the pagoda (baota) for which the place was named could be seen from almost any point in the city, towering 25 meters above the red-clay hillocks under a mantle of blue sky, its brick and bluestone looking golden from afar. Constructed in 1764 during the Qianlong era to ward off the water demons of the Xiao River that brought calamitous floods upon the land, it became a local landmark. It was only natural that the stretch of fertile soil below the pagoda should be named Baotajiao (“foot of the pagoda”). During the Cultural Revolution’s “smashing of the four olds,” however, it was renamed the Qixin (“one mind”) production brigade.

Now the spacious threshing ground of the Qixin brigade’s Huziping production team was packed with heads and spears. Outside the meeting space, militiamen wearing uniforms and red armbands stood guard. Apart from members of the production brigade, cadres, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Youth League members, and poor-peasant association (PPA) representatives from the Jianshe and Xiangyang brigades brought the attendance to more than one thousand. At one end of the threshing ground, a large table and several wooden chairs had been set up to serve as a rostrum. In order to enhance the impact, the theme of the meeting had not been divulged in advance. People whispered in each other’s ears asking what it was all about.

Map 5 Communes of the former Shangguan District

Daoxian’s climate is at its hottest in August, and invisible heat waves rippled from the fields under the broiling sun. The meeting began just as the heat became oppressive. After the usual ceremonial preludes of studying the “highest directive” and respectfully wishing long life to Chairman Mao, the deputy head of the Shangguan Commune seize-and-push group, Zhou Yuanji, delivered a report. Lacking a microphone, he had to shout each sentence at the top of his voice: “Poor and lower-middle peasant comrades, the black elements of Simaqiao have headed for the hills! Weapons have been seized at the No. 2 High School for a coup d’état! Poor and lower-middle peasants in Districts 8, 10, and 11 have taken action and killed black elements! What should we do?”

The assembly fell silent. Having been given no advanced warning, everyone looked at each other in blank dismay, wary of making a careless remark. Seeing the lack of response, Zhou Yuanji continued, “Shouldn’t we kill some of those scheming, lowlife black elements?”

The meeting erupted into chaos as everyone began talking.

Zhou Yuanji went on: “Right now, no permission is needed for killing. The poor and lower-middle peasants are the Supreme People’s Court, and killings can be carried out with their agreement.” He paused for a moment while looking about portentously and waiting for his words to sink in, then shouted, “Today we’ll take the knife to puppet security chief He Guangqin to serve as an example.”

As soon as Zhou finished his report, the Qixin brigade’s Youth League secretary, Luo Teliang, mounted the podium and pronounced judgment on behalf of the peasant supreme court, and a group of militiamen came from behind dragging a hogtied He Guangqin. After Luo Teliang finished reading out a “judgment” that commune Youth League secretary Wu Rongdeng had drafted, he imitated the drawn-out diction of movie judges to proclaim, “I now represent the Supreme People’s Court of the Poor and Lower-Middle Peasants in sentencing He Guangqin to death, to be carried out immediately!”

He Guangqin thought he was only going to be subjected to the usual public denunciation, and when he heard his death sentence pronounced, he was so terrified that he fell senseless to the ground and soiled his pants. Holding their noses against the stench, two militiamen dragged He Guangqin like a dead dog to a harvested paddy field in front of the threshing ground. After forcing him to kneel, they brought a saber down upon his neck. Blood spurted all over the fragrant soil. Eyewitnesses said that the execution was so poorly handled that He Guangqin’s body continued to twitch after he was beheaded.

Zhou Yuanji had been just an ordinary 33-year-old plant breeder at Shangguan Commune’s agrotechnical station, but once the Cultural Revolution began and he became deputy head of the commune seize-and-push group, his temperament changed radically. Sloughing off his slack habits, he became fervent, speedy, and resolute, earning repeated commendations from his leaders.

This killing rally had been prompted by the Yingjiang reporting conference on August 21. Shangguan District People’s Armed Forces Department (PAFD) head Liu Houshan and others had hurried home and convened a cadre meeting that resulted in the organizing of a militia and establishment of a militia base area in the Qixin brigade, setting up roadblocks and sentry posts and closely monitoring all black elements. Liu Houshan made an unmistakable knife-like gesture with his hand and said, “We have to make the first move against class enemies who are habitually disobedient, troublesome, and hard to manage.” The cadres had decided to kill He Guangqin, who had served as a public-security head under the Kuomintang (KMT), as a means of mobilizing the masses. Liu Houshan had clapped Zhou Yuanji on the shoulder and said, “We’ll hand over operations here in Qixin to you.” Zhou Yuanji was very excited to have a leader place so much trust in him, and the on-the-spot killing rally was his first salvo, with representatives from the neighboring Jianshe and Xiangyang brigades invited to attend and learn from the rally.

After the killing rally at Baotajiao, Zhou Yuanji went straight to the Jianshe brigade in Longjiangqiao to arrange an even more spectacular killing rally.

On the morning of August 24, the beating of gongs could be heard, sometimes slow, sometimes urgent, as large and small groups of people converged on the roads leading to the Longjiangqiao transformer substation. Four troupes similar to dragon dance teams wound their way from the Dongfeng, Dongfang, Dongjin, and Dongyuan brigades. Those walking in front wore dunce caps and placards and struck cymbals and battered washbasins that they held in their hands. Bound together and escorted by armed militia, they included men, women, old people, and children. Behind this troupe ran a bunch of women dragging their kids to see what was happening, even though they would lose work points for attending.

“Granny Jiang, going to the rally at your age?”

“Sure, I’m going! We haven’t seen anything so grand in years! How could I miss it!”

“You must have seen a lot of rallies at your age. Leader Zhou says this is unprecedented.”

“Yes, I saw lots back when you were young, and they were splendid, but nothing like this.”

“Better hurry! If you’re late, you’ll have to stand in back and you won’t be able to see a thing.”

“You’re right. I lost out last time, standing in the back. Hey, Sister He, let me be blunt: last time your son really messed up, hacking at He Guangqin so many times to cut his head off.”

“It wasn’t his fault—they gave him such a dull blade!”

“This time they’ll have sharpened it.”

“They’re not using a saber this time. Leader Zhou says they’re using a ‘foreign method.’ ”

“Really? You’d better get going!”

By the time the old ladies and housewives reached the plaza at Longjiangqiao’s Shitouling transformer substation, it was already packed with more than 3,000 people. In order to prevent class enemies and the Revolutionary Alliance from sabotaging the event, Zhou Yuanji had gotten permission from district PAFD head Liu Houshan to borrow dozens of core militiamen from the nearby Baimadu militia command post to maintain order at the rally. The attending cadres and commune members stood in areas chalked in for each production brigade. Dozens of black elements and offspring knelt in a line with their heads bowed on the stage, which was festooned with red flags and a large red banner proclaiming, “Carry the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution to the End!” Zhou Yuanji, who had instructed each brigade to submit black elements for killing,1 stood on the stage, eyes directed solemnly ahead of him as people from surrounding localities continued to crowd onto the plaza.

Finally the rally began, and as soon as Zhou Yuanji opened his mouth, there was no more talking or coughing, and no children whimpered as everyone pricked their ears to catch whatever sound issued from Leader Zhou’s lips. Only the wind continued to rustle through the bamboo and tree leaves.

“Today we are here to hold a large on-the-spot rally. Today’s rally is the second signal flare our Shangguan Commune is sending up to suppress the class enemy following the first signal flare at the Qixin brigade yesterday. Each brigade needs to take immediate action to thoroughly puncture the arrogant bluster of the class enemy.”

After that, the six black elements chosen by the various production brigades were executed by firing squad. When the onlookers realized that the “foreign method” was actually just shooting, they couldn’t help but feel disappointed. This method had already been used back during Land Reform: people were bound up, had placards hung around their necks, and knelt down, and then the muzzle of a gun was placed at the back of their heads. Boom! The tops of their heads blew off, and their bodies toppled forward as red blood and white brains sprayed out, none of it getting on the executioners, unlike that fellow He using a saber and getting drenched. This method was good enough, but it was nothing new.

After the rally ended, the commune’s administrative cadres stayed behind for a brief meeting during which each was assigned to several brigades for supervising and encouraging killings. We read the notebook Zhou Yuanji kept that year, which showed the specific brigades assigned that day to He Ruidi (commune head), Xiong Liji (commune deputy CCP secretary), Zuo Changci (commune organization cadre), Yang Guolong (Shangguan District deputy CCP secretary), Wu Rongdeng (commune Youth League secretary), and Yang Daoming (commune CCP secretary).

What exactly did these comrades do in the production brigades? An illustration is commune deputy CCP secretary Xiong Liji’s actions at the Shuinan brigade. Located on the outskirts of Daojiang, Shuinan was well known as one of Daoxian’s most prosperous villages, producing citrus fruits and melons that were the best in the county. The members of this brigade were also relatively prosperous, and it had quite a few black elements, but several of these households had members working outside the county, some as fairly senior cadres. When Xiong Liji called a meeting to discuss killings, the brigade’s cadres showed a marked reluctance, and Xiong finally became so agitated that he drew out a dagger and drove it into the meeting table: “This is the watershed between revolutionary and counterrevolutionary. Who here is unwilling to distinguish himself from the class enemy?”

The knife handle quivered under the lantern light, and the faces of the cadres blanched white. Soon after that, the brigade drowned several class enemies and offspring.

Under the supervision and encouragement of district and commune cadres, the other production brigades likewise took action one by one, and in the eight days up until August 30, Shangguan Commune’s 12 brigades killed a total of 112 people.

The Task Force’s investigation verified that under the arrangements and direction of district PAFD commander Liu Houshan, commune CCP secretary Yang Daoming, and others, Shangguan Commune killed a total of 173 people during the Cultural Revolution massacre, mainly through the use of guns, knives, and drowning. One of the victims was Du Zhuzhong, an Army veteran and poor peasant from the Dongfang brigade who had rendered distinguished service during the Korean War. The Task Force’s inquiries established that Liu Houshan personally talked grassroots cadres into “doing away with” Du Zhuzhong because Du had dared to argue with him in the past.

As mentioned earlier, during the Cultural Revolution “killing wind,” Shangguan Commune was under the jurisdiction of the subsequently eradicated Shangguan District. Readers may wonder why this point is important enough to keep repeating. The reason is that the massacre occurred along administrative boundaries, from the districts to the communes to the production brigades, each level inciting the next one down to carry out killings. I can confidently say that there were almost no genuine instances of poor and lower-middle peasants spontaneously rising up against landlords and rich peasants unless it was out of personal revenge or to take possession of women or valuables, and that apart from these personal factors, the killings showed a clear chain of command from top to bottom. The adjustment of administrative boundaries in 1984 obscured this process when the Task Force investigated the killings, resulting in many errors and misunderstandings.

Viewing the sequence of events in Shangguan District from the perspective of the original boundaries, we see that the jurisdiction of Shangguan District (also referred to as District 1) included not only Shangguan Commune but also Futang (now under Meihua District), Dongmen (now under Qingxi District), and Wanjiazhuang (now under Qingtang District), forming the northern, eastern, and southern coordinates of a crescent shape enveloping the county seat of Daojiang. Adding Yingjiang Commune in the west completed the circle and ensured that Shangguan District, like Yingjiang Commune, became a key battleground between the Red Alliance and Revolutionary Alliance.

Due to constant infiltration by the Revolutionary Alliance, the four communes in Shangguan District experienced varying degrees of division within the “class ranks,” with a small number of grassroots cadres and poor peasants switching over to the Revolutionary Alliance. For example, the core militia commander of Shangguang Commune’s Shangguan production brigade, Li Chenggou, and some others brought guns to the No. 2 High School, and Li became head of the “Poor and Lower-Middle Peasant Revolutionary Rebel Headquarters” under the Revolutionary Alliance, while simultaneously serving as commander of the “Verbal Attack and Armed Defense Command Post.” Such people were considered much more destructive than the average black element, because they masked the “reactionary character” of the Revolutionary Alliance. As a result, the killings in Shangguan District targeted not only class enemies but also a significant number of these “turncoats,” a term applied specifically to poor peasants and grassroots cadres who sympathized with Revolutionary Alliance viewpoints or joined Revolutionary Alliance organizations.

In Dongmen Commune’s Youyi brigade, a 26-year-old poor peasant named He Shanliang was considered one of the county’s most outstanding students of Chairman Mao’s works and had been an active participant in the Socialist Education movement. During the Cultural Revolution massacres, one would have expected him to be one of the most enthusiastic killers and least likely to be targeted. Instead, he perversely joined the Revolutionary Alliance and was consequently sentenced to death by the peasant supreme court, which declared him guilty of secret communications with the “Revolutionary Bandits” and undermining the foundations of socialism by stealing two cabbages from his production team during the hard times of the Great Famine in 1960. This second charge might strike the reader as ludicrously petty, but in 1960, when even chaff was hard to come by, one cabbage could save a life. An estimated 38,000 people starved to death in Daoxian during the famine, partly because of people such as He Shanliang, which makes it less surprising that during the Youyi brigade’s meeting to discuss the killing, the poor peasants unanimously demanded He’s death. Heeding the call of the masses, brigade CCP secretary Jiang Shiming2 agreed: “Do away with him along with the class enemies.” There were other such cases in other communes of Shangguan District.

In Wangjiazhuang Commune’s Hongqi brigade (Xialongdong Village), He Ziyuan was a CCP member and principal of the Shenzhangtang Elementary School, and it may never have occurred to him that he would be designated a black element during the “killing wind.” He was said to have been brought to justice by his village’s poor peasants because he joined the Revolutionary Alliance. (A former Revolutionary Alliance leader had no recollection of He Ziyuan joining any of the alliance’s organizations; it appears that he at most supported Revolutionary Alliance standpoints.) When the production brigade met to discuss who should be killed, the PPA and Cultural Revolution Committee (CRC) chairmen said He Ziyuan absolutely had to be killed. The first time He Ziyuan was taken out to be killed with several class enemies, he recited a quote from Chairman Mao: “The Great Leader Chairman Mao instructs us: the core power that guides our undertaking is the Chinese Communist Party, and the theoretical foundation that directs our thinking is Marxism-Leninism.” He added, “I’m a party member, and whatever I’ve done wrong should be handled by party discipline and national law. Your Supreme People’s Court of the Poor and Lower-Middle Peasants is not qualified to kill a party member.” Some of the Hongqi brigade cadres thought this made sense, and they had the class enemies killed, but locked He Ziyuan up again to await a decision from above.

At that time, He Ziyuan’s production team pointed out that although he was a CCP member, he had turned his back on the revolution and therefore should be handled as a “turncoat,” so he was taken out a second time to be killed. But He Ziyuan played the same old trick, reciting a quote from Chairman Mao: “The Great Leader Chairman Mao instructs us: policy and strategy are the lifeblood of the party; leading comrades at every level must pay close attention to this and never disregard it under any circumstances.” He added, “Poor and lower-middle peasant comrades, comrades of the revolution, in carrying out our revolutionary work we must do everything in accordance with party policy. If you want to kill me, you must first expel me from the party. I’m still a party member, and if you kill me, you’re killing not only me but also a party member and the party!”

Amazingly, this drivel was actually effective in prompting dissention within the brigade. Some said, “Who cares, just kill him!” But others said, “It’s fine to kill class enemies, but killing a party member requires instructions from the upper level.” So again, He Ziyuan’s life was spared.

The production brigade’s militia leader, He Gouxiang, telephoned the commune to request instructions, and the call was taken by Jiang Zhi, the commune’s Red Alliance head and a member of the commune CCP committee’s organization, propaganda, and supervision committee. Jiang didn’t dare make a decision without authorization, so he telephoned Peng Yuming, the district’s Red Alliance head and a member of the district CCP committee’s organization committee. Peng immediately directed him: “If the masses demand that he be killed, it doesn’t matter if he’s a party member. Kill him and then we’ll discuss it.”

After obtaining these instructions, He Gouxiang laughed and said, “A weasel has three farts to save his life. Let’s see what He Ziyuan comes up with now!” This time He Ziyuan’s glib tongue was unequal to the task, and he was finally put to death.

Why was such trouble taken to kill He Ziyuan? A comrade from the Task Force explained that the He family had a fairly high-class status, and before killing He Ziyuan, the brigade had already killed his wife and son. The brigade’s cadres were afraid that if they spared He’s life, he would eventually take revenge for his family, so they needed to find an excuse to kill him.

During the Cultural Revolution massacre, Shangguan District killed a total of 415 people (including 46 suicides). The district’s main leaders who incited and planned the killings were deputy CCP secretary and propaganda committee member Yang Guolong; CCP committee organization, propaganda, and supervision committee member Peng Yuming; PAFD commander Liu Houshan; and district women’s committee chair Wei Shuying.

In the district’s four communes, the main people responsible can be categorized as in the following table:

Note: in a few cases, an individual held more than one position.

The Shangguan Commune plant breeder Zhou Yuanji, whose role in the killings is described so colorfully above, was only a pawn and henchman in the chain of responsibility.

I would like to make three observations regarding the cadres involved:

(1)It’s not the individuals who are important, but rather the official titles. I have often imagined these people as mere actors selected by some unfathomable and mysterious hand to play their role in this cosmic tragedy and to provide a lesson for our great nation. I have the names of more than 200 county, district, and commune cadres who are directly implicated in the killings, but there is little purpose in assigning personal blame; only raising national consciousness can prevent such a tragedy happening again. I originally intended to give no names at all in this book, but only the positions of those responsible. However, I later decided that the information was necessary to allow others to verify the accuracy of this text. I myself have sometimes found its content difficult to believe, and if it were made more obscure, later generations might suspect it was pure fiction. Things published in black and white must be recorded word for word like sworn testimony in a court of law.3

(2)This listing reveals that the main people responsible for the killings were seldom CCP secretaries but were most often deputy CCP secretaries, committee members, PAFD commanders, and public-security deputies. Is this because most of the top officials (secretaries) had reservations about the killings? Or were their policy or strategic standards of a higher caliber? This is a point that those who experienced the Cultural Revolution will implicitly understand. The Cultural Revolution was a mass movement launched by Mao as the leader of the CCP, and it involved the top-down mobilization of nearly every individual who lived and breathed in China. None of the abominations of the Cultural Revolution were unique to that period, but its adherence to the slogan “Rebellion is justified” ensured that it proceeded largely, though not entirely, in accordance with Mao’s personal will. The guiding principles of the Cultural Revolution, the “Sixteen Articles,”4 stipulated: “The emphasis of this movement is to purge from the party those in authority who take the capitalist road.” As a result, in the early stage of the movement, the persons in authority or “first in command” at every level, from the Central Committee down to every local work unit, came under attack to some degree. It was under this general environment that the Daoxian massacre took place. Consequently, apart from cadres who had already “stepped forward” to “strike a revolutionary pose,” those who had “stepped aside” as “capitalist roaders” had little role to play, whether they agreed with the killings or not. By the time they achieved “Liberation” and resumed their administrative duties, the Daoxian massacre was a page that had been turned in the book of history.

(3)As mentioned before, but which bears repeating here, during the Cultural Revolution killings in Daoxian, the real power was held by the various levels of seize-and-push groups, with the county PAFD at their core. Evidence indicates that in the vast majority of cases, killings were incited and arranged through this channel.