Samizdat: A culture of readers and networks

What was samizdat?

Samizdat developed in the second half of the 1950s on the crest of the poetry boom that saw newly famous poets such as Evgenii Evtushenko perform to full stadiums. Enthusiasm for poetry inspired cultural initiatives that were organized by interested citizens rather than any official structure, such as the weekly gatherings on Mayakovsky Square from 1958 onwards, where large groups of young people would read poetry out loud. In the centrally organized Soviet cultural sphere that had just emerged from Stalinism, such spontaneous initiatives were a novelty.

Poets who came onto the scene after Stalin’s death, such as Evtushenko, Andrei Voznesenskii, Bella Akhmadulina, Robert Rozhdestvenskii and others, represented one group that captured the attention of the reading public. Another such group were the poets of the Silver Age who had been popular in the years preceding the 1917 revolution. In many cases their work had not been republished under Soviet rule, and some, notably Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelshtam and the returned émigré Marina Tsvetaeva, produced a significant body of work after the revolution that was never available in print. Silver Age texts re-emerged slowly during the late 1950s and 1960s; they had a huge influence on reading tastes and ultimately on the writing techniques of new poets.1 New official editions notwithstanding – and such editions were always selective – Silver Age poets were not widely published. Readers who had access to their texts – for example because they owned pre-revolutionary editions – would copy out poems, frequently by hand, and share them with their acquaintances. Samizdat was born. This process is described in many written first-hand accounts, and the respondents to our online survey of samizdat readers, discussed in detail in Chapter 2, confirm its basic mechanics. Respondent #22 (b.1976) remembers that ‘my first [samizdat] texts were my mum’s handwritten copies of Esenin’s poetry’.2 One respondent dutifully recorded the characteristic mixture of old and new poetry: ‘A lot of poetry was circulating. People were copying Tsvetaeva, by hand, from the books published in tiny print runs in the 1920s, and [Nikolai] Gumilev, but also [Naum] Korzhavin and [Joseph] Brodsky. I myself copied little, but provided many texts for people to copy.’3

The term ‘samizdat’ became attached to this phenomenon in the 1960s, but it predates the mass practice of circulating texts in this way. Its origin is commonly attributed to Nikolai Glazkov who, as early as the 1940s, would give self-bound typescripts of his prose miniatures to his friends, adorned with the word samsebiaizdat (‘self-published’ or ‘self-publishing house’) in the place where you would expect to find the name of the publishing house. Samsebiaizdat was a pun on the abbreviated names of official publishing houses such as Litizdat (Literary Publishing House) or Gosizdat (State Publishing House).4 This means that samizdat was, from the very beginning, also an outlet for contemporary writers who could not, or did not try to, publish their texts in the official press. Some of the best-known Russian writers of the late twentieth century owe all, or most, of their reputation to samizdat. Among them are Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) – whose Arkhipelag Gulag (The Gulag Archipelago, published in Paris in 1973) eclipsed the fame of the earlier, officially published Odin den’ Ivana Denisovicha (One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, 1962) – and the poet Joseph Brodsky (1940–1996). Both are Nobel Prize winners. Others include Venedikt Erofeev (1938–1990), Elena Shvarts (1948–2010) and Dmitrii Alexanderovich Prigov (1940–2007).

From the mid-1960s onwards, samizdat began to include material relating to history, religion, politics, public affairs and other topics. The non-literary texts that made samizdat famous to an international audience were generated by the members of the growing human rights movement (known as ‘dissidents’) and included letters of protest and news items, including the periodical human rights bulletin Khronika tekushchikh sobytii (Chronicle of Current Events, 1968–1983). The Chronicle was smuggled out to the West and republished in English.5 Western radio stations, such as the BBC, Voice of America, Deutsche Welle and Radio Liberty (RL)/Radio Free Europe (RFE), the latter founded for the purpose of broadcasting to the Eastern bloc countries, broadcast such materials back to the Soviet Union, hugely increasing the audience for samizdat.6 Samizdat proper, that is – textual material produced inside the Soviet Union – was increasingly supplemented by texts published abroad and smuggled back into the Soviet Union, a practice known as tamizdat (published over there). Many iconic texts, including Solzhenitsyn’s novels and Brodsky’s poetry, were published abroad, often decades before the first Soviet or Russian editions.

The texts circulated in samizdat have been scrupulously collected and, in many cases, reproduced in print form. By now, lesser-known literary texts and political writings have been collected, too. The following overview of sources is indicative, but does not make a claim to completeness.

Two major sources exist in both book form and online: Viacheslav Igrunov’s Antologiia samizdata (Anthology of Samizdat) is divided into sections for poetry, prose and social journalism (publitsistika).7 The section on unofficial poetry collected in Samizdat veka (The Samizdat of the Century) has been incorporated into the Russkaia virtual’naia biblioteka (Russian Virtual Library).8 The archives and records of Radio Liberty, which broadcast samizdat back to the Soviet Union, are at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives, with additional material held in the Open Society Archive at the Central European University in Budapest; many of the items of samizdat broadcast were made accessible online in 2016.9 Different branches of the Memorial Society hold extensive samizdat archives, many of them from private collections.10 The archive of the Forschungsstelle Osteuropa (Research Centre for East European Studies) at the University of Bremen holds a sizeable samizdat collection, sourced from private archives, alongside what might well be the largest existing collection of samizdat periodicals.11 The University of Toronto’s Project for the Study of Samizdat and Dissidence offers a database of Soviet samizdat periodicals, illustrated timelines of dissident movements, interviews with activists, and maps, attempting to render part of the process visible. Of particular value are the digital reproductions of samizdat periodicals, some of which have been made fully searchable.12 The Keston Center at Baylor University, Texas, now holds the archives of Keston College/the Keston Institute, an organization founded in the UK in 1969 with the aim of researching religion in communist societies; the Institute amassed a large amount of religious samizdat.13 The Tsentr Andreia Belogo (Andrei Belyi Centre) in St Petersburg is continuing to expand its digital archive of literary samizdat.14 The ImWerden project, which set itself the ambitious goal of becoming the online library of the RuNet, the Russian internet, maintains a special section for ‘Second Literature’: namely, texts not officially published in the Soviet Union; the collection is large and texts are downloadable.15 The now-defunct website of the International Samizdat Association published a list of archives holding samizdat collections.

Thus, if we consider samizdat to be merely a body of texts, the scholar or interested layperson will find plenty of sources. However, this is a reductive interpretation. Indeed, the question ‘What was samizdat?’ is hotly debated. A roundtable at the Memorial Society in 2014 asked researchers to consider precisely this question – ‘Chto takoe samizdat?’ (What is samizdat?).16 Contemporary research has evolved beyond the focus on samizdat as a sociopolitical phenomenon that is often fixated solely on the content transmitted by the texts. In the introduction to the essay collection Samizdat, Tamizdat and Beyond, editors Friederike Kind-Kovacs and Jessie Labov invite their contributors to ponder whether samizdat was a publishing practice, a reading practice, a set of texts, or a state of mind; the collection stresses the function of samizdat as a media form.17 The Russian historian Alexander Daniel calls samizdat a ‘mode of existence of the text’,18 while the historian and archivist Elena Strukova discusses its importance as a ‘memorial to book culture in the late 20th century’.19 The Canadian researcher Ann Komaromi, who runs the Project for the Study of Samizdat and Dissidence, asks whether samizdat was a medium, a genre, a corpus of texts, or a textual culture,20 an approach she developed further in her recent monograph.21 The Italian scholar Valentina Parisi has produced a richly illustrated volume focusing on the samizdat reader that considers literary and cultural theory alongside the paratextual aspects of samizdat periodicals.22

Moreover, there are several dedicated outlets and discussion forums for questions relating to samizdat: the Memorial Society publishes a biannual almanac, Acta Samizdatica: Zapiski o Samizdate (Acta Samizdatica: Notes on Samizdat), which includes new research alongside archival publications. There are several bespoke Facebook groups facilitating the exchange of information, including the International Samizdat [Research] Association community and the Samizdat group.23 This means that there is plenty of material available on the content transmitted by samizdat as well as on the material medium. Yet, surprisingly, little research has been conducted on the process of reading, and even less on the ordinary reader of samizdat. Or perhaps this should not come as a surprise, because the largest group involved in samizdat is notoriously difficult to research.

Samizdat readers

Are samizdat readers dissidents?

The literature – and public opinion, too – commonly understands samizdat as a function of ‘dissidence’, namely, the many forms in which different groups or individuals protested against the Soviet regime’s practices. This is true in one direction only: all dissidents were involved in samizdat, which provided them with alternative social and communication networks. Indeed, reading samizdat was often the first step towards dissidence. To put it differently, reading uncensored texts inspired ‘uncensored’, independent thought. For a significant minority, the next logical step was the writing and circulation of their own texts, and/or various forms of activism, from the dissemination of texts to the creation of entire samizdat periodicals. Some actions were more or less political, such as the letters intellectuals wrote to protest against the arrest, in 1965, of Andrei Siniavskii and Yulii Daniel for publishing abroad;24 the demonstration on Red Square on 25 August 1968, by eight people, against the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968;25 or the foundation of the Moscow Helsinki Group, the oldest human rights group still operating in Russia, in 1977.26

One example of how reading forbidden literary texts led to a critical reassessment of Soviet ideology is the story of Sergei Khodorovich, who read Polish author Stanislaw Lem’s 1971 collection The Star Diaries. His gradual move towards active dissidence saw him becoming one of the managers of the (unofficial and illegal) Public Foundation for Political Prisoners and their Families (Solzhenitsyn Foundation) in 1977, and culminated in arrest and a prison camp sentence.27 The historian Leonid Zhmud’ remembers how samizdat literature formed his political opinion, ‘and so my modest role as a distributor of anti-Soviet literature was exceptionally beneficial for my subsequent work as a historian’.28 The art historian Igor Golomshtok, who did not consider himself an active dissident, also remembers his own disagreement with the regime in the 1960s as being inspired by literature: ‘We did not protest against the regime, but against the regime’s lies … This we learned from the songs of [Alexander] Galich and [Bulat] Okudzhava, the poems of [Joseph] Brodsky, the stories and later, the novels of [Vladimir] Voinovich, not to mention the Russian classics from Pushkin to Mandelshtam, Tsvetaeva and [Andrei] Platonov.’29 Much of Soviet dissent was even more restrained and often did not directly engage with the regime at all. The poet Olga Sedakova remembers the mature cultural underground of the 1970s as follows: ‘For us, culture in its broadest historical aspect signified the very freedom and soaring height of spirit denied to us by the Soviet system … We all emerged from some kind of protest movement, which was not so much political as aesthetic or spiritual resistance.’30 The degree to which samizdat was persecuted depended on the nature of the texts circulated. Naturally, texts engaging with the political situation and human rights abuses in the Soviet Union past or present, such as Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago and the Chronicle of Current Events, were more likely to lead to reprisals than ‘purely’ literary texts.31

Samizdat texts and the channels by which they circulated were instrumental to the functioning of informal networks, including those that readers, both Russian and Western, have in mind when they say ‘dissidents’. Dissidents are ‘all those who actively protested against the regime in one way or another: by signing protest letters, participating in demonstrations, or serving a camp sentence or term of exile’.32 Most often, dissidents are equated with the Soviet human rights activists (pravozashchitniki, literally ‘defenders of rights’). The human rights activists acted on a moral imperative but did not have a vision or indeed the desire to fight the system; indeed, their first ‘action’ was accompanied by an iconic slogan exhorting the authorities to ‘Respect the Soviet Constitution’.33 The activity of most groups that were critical of aspects of the official system was characterized by an emphasis on the provision of information and education via the written word.

It is in this function, as an information channel for dissidents, that veteran human rights activist Liudmila Alekseeva describes samizdat in her seminal survey Istoriia inakomysliia v SSSR (The History of Dissent in the Soviet Union). Characteristically, the section ‘The Birth of Samizdat’ is embedded into the chapter on human rights activists, although Alekseeva dutifully mentions the origins of samizdat in the circulation of poetry in the 1950s.34 The English translation of the book differs in structure and carries additional information; here, the phenomenon of samizdat is described as ‘The Core of the Movement’ in a chapter dedicated to ‘The Communication Network of Dissent’.35 The tendency to treat samizdat as a function of dissidence can be observed in contemporary research, too: in 2017, the literary scholar and editor Gleb Morev published a book of twenty narrative interviews with Soviet dissidents, who all talk about samizdat as a function of their daily life, while their reading practice is reduced to a footnote.36 The University of Toronto’s Project for the Study of Samizdat and Dissidence implicitly identifies dissent and samizdat in its very title.

However, while all dissidents read samizdat, by no means all readers of samizdat were active dissidents. The dissidents numbered in the hundreds, the readers of samizdat at least in the hundreds of thousands. This is easier to understand when we consider that unofficially reproduced and circulated texts included a large number of works that were neither literary nor in any sense related to current affairs, but rather to everyday life or even leisure. The poet Lev Losev identifies six categories of samizdat texts: literary; political; religious and philosophical; mystical and occult; erotica; and instructions.37 Elizaveta Starshinina, a journalist from Irkutsk, remembers the early 1980s: ‘Practically everybody had some samizdat at home, depending on their interests and level of education: instructions for yoga and urine therapy, handbooks for herbal remedies, guitar tabs of Beatles songs and even recipes for pickling vegetables at home. All this circulated actively, because there was no other way of obtaining information.’38

Samizdat was irrepressible. And it owed much of its vitality to the fact that it lacked any kind of central organization. But now this very guarantor of success constitutes a serious impediment to any attempt to reconstruct how people actually read samizdat and who these people were.

Silent witnesses

For the researcher, the biggest challenge is that samizdat culture resists most attempts at recording it using our usual tools. For a start, the only element of this culture that is easily accessible is the text itself, preserved in a private or public archive. But this text is intriguingly and frustratingly silent. If we are lucky, a preserved archival copy gives away two names: that of the author and that of the last person to read it. Even if other sources confirm that both these people participated in the samizdat chain – and that is not always the case – the preserved fragments are too few and far between to enable us to reconstruct the journey and readership of a given individual text. Samizdat’s informal nature is only one reason why this journey is hard to trace. Its de facto illegality compounds the problem, as those involved often concealed their identity. Indeed, it is impossible to imagine a samizdat text accompanied by something like a borrowing sheet listing its readers. Only very few people marked their samizdat texts with their names – after all, an inscription could become incriminating evidence. Moreover, none of the statistics normally used by book historians are available, for example print run, editions, sales figures, reviews and translations. While printed books and journals feature information about editors, publishers and print runs, and libraries have borrowing registers, virtually no similar records exist for samizdat.

During an interview with Natalia Volokhonskaia, a samizdat typist and poet from Leningrad, we discussed the samizdat journal Kolokol (The Bell), which circulated in the 1960s and earned its makers lengthy prison camp sentences.39 A scheme illustrating the circulation of the journal was part of the investigation file discovered in the KGB archive. When I remarked how interesting it was to look at the reconstruction of this small network, she replied: ‘To make this possible you needed (a) observation, (b) interrogations and (c) people telling the truth during these interrogations. That’s possible for Kolokol, for one copy, or for a couple of issues. But all the rest?’40 Volokhonskaia’s remark is instructive, locating samizdat reading firmly within the field of activities which people routinely concealed from those around them. By contrast, generalized accounts of the workings of samizdat networks are easy to find. This one is by Liudmila Alekseeva:

The mechanism of samizdat was like this: the author would print their text in the way that was most accessible to a private individual under Soviet conditions – i.e. on the typewriter, in a few copies – and give these copies to his acquaintances. If one of them considered the text interesting, they would make copies from the copy they had got and give them to their acquaintances, and so on. The more successful a work the more quickly and widely it would be disseminated.41

This is a generic story lacking individual detail, but more importantly, its focus is – and this is typical – on the process of textual production at the expense of the process of reading. It is of course an exaggeration to say that the reading of samizdat left no traces at all. We find such traces, for example, in private diaries held in archives, as well as in published memoirs.42 But, as a rule, these reminiscences make no attempt to establish or analyse the way in which reading networks functioned. In some isolated cases, specific networks were documented out of necessity. To give an example, Yurii Avrutskii, the organizer of what he called a ‘club’ for reading samizdat, decided to begin a register of texts and readers but encrypted the entries for fear of incriminating his friends should the register be found. The register has survived and can be seen among the papers of Avrutskii’s private archive, held by the Memorial Society in Moscow. The papers are a valuable source precisely because Avrutskii has commented on them. However, without the owner’s explanatory comments, records of this kind are of limited use to the researcher.43

Sources that focus explicitly on samizdat reading exist but are limited in scope for various reasons. One is a series of interviews conducted by Raisa Orlova, the philologist and wife of the well-known dissident Lev Kopelev, in Germany and other Western European countries in the early 1980s. In collaboration with the newly founded Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen, Orlova interviewed recent émigrés from the Soviet Union about their experience with samizdat. Her sample was small, however, and limited to people who had left the USSR, often as a result of persecution. Many of her respondents were active dissenters or prominent writers and consequently much more involved in samizdat than the average reader. What is more, they naturally protected their acquaintances who had remained in the Soviet Union by not giving names. Over the space of three years, Orlova managed to conduct just over fifty interviews. At the moment, they are held in a specialist archive, not available to the general public.44 Similar restrictions hold true for contemporary initiatives, for example the Memorial Society’s annual roundtables on samizdat45 and the interviews with samizdat activists published on the website of the Project for the Study of Samizdat and Dissidence.46 A number of memoirs contain longer accounts of reading samizdat.47 Yet, once again, these are individual accounts that tell us little about the workings of the networks within which samizdat flourished, and often nothing about readers other than the author themselves. So the statement made by Elena Strukova, head of the Fond netraditsionnoi pechati (Collection of Non-traditional Print) at the Russian State Historical Library (GPIB), holds true: ‘Reading literature that was not even forbidden, but of which there was a deficit, was a mass phenomenon – however, there are very few testimonies.’48 Quantitative analysis of samizdat reading on a large scale is patently impossible.

Much more than ‘just’ a reader

For technical reasons, I will refer to samizdat as a ‘literary process’ in this section, without distinguishing between literary, political, religious and other kinds of samizdat or, within literary samizdat, between new literature that existed only in samizdat and pre-existing texts that were merely copied in this way. This is solely for the purpose of illustrating the mechanism of text production, multiplication and distribution.

Any literary process requires writers, middlemen and readers. Moreover, for a text to remain accessible to new readers – in print, or in circulation – it must be endorsed by earlier readers. In this respect samizdat was no exception. However, the externalities of textual production, distribution and, ultimately, reading itself differ significantly from the ones we study when researching ‘traditional’ printed texts or even manuscripts. A look at these differences will afford us a shortcut in understanding why it is so crucial to study the samizdat reader if we want to understand the process as a whole.

We might want to begin by assessing the position of samizdat within Soviet textual culture and its relation to print culture in particular. Samizdat existed precisely because the state had monopolized printing. Yet it was not completely divorced from print. Rather, samizdat represents a hybrid genre49 in technical, organizational and material terms, situated as it was within a highly developed print culture, partly overlapping with it and, for certain segments of society, increasingly replacing it. As the name ‘samizdat’, forming an analogy to official providers such as Gosizdat, already intimates, samizdat was an alternative variant rather than a separate phenomenon altogether.

In technical terms, samizdat was a hybrid because in its iconic form it was produced with the help of a typewriter. A typewriter is itself a hybrid, fit for private use but producing a limited number of absolutely identical copies in standardized type. In organizational terms, samizdat was a hybrid because segments of it were clearly modelled on the official literary process, leaving out censorship. This is particularly apparent when we consider the literary journals of the 1970s with their editorial procedures, subscription schemes and publication schedules; these are discussed in Chapters 5 and 6. Samizdat was a hybrid in material terms, too, because a significant proportion of the circulating literature existed in print and was merely reproduced and disseminated by hand because no new print editions were available. This concerned above all pre-revolutionary literature and contemporary texts produced in small print runs, for example the hugely popular science fiction of the Strugatsky brothers. A related issue is the fact that many samizdat writers had some publications in official print. Prominent examples include Alexander Solzhenitsyn, whose One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich caused a sensation when it was published in the official journal Novyi mir (New World) in November 1962, and the officially published poetry collections of Varlam Shalamov, whose famous Kolyma Tales circulated only in samizdat.50 Most of the poets who defined Leningrad unofficial culture in the 1970s had published officially at some point.51

A further complicating factor was tamizdat, the publication abroad of texts that had no chance of publication in the Soviet Union. Tamizdat was often realized through émigré publishing houses or specialized Russian-language publishers.52 Prominent examples of works published in this way include Leonid Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago and Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago. Copies inevitably made their way back into the USSR, where they would be typed out or reproduced by other means, thus ‘returning’ to samizdat. From the mid-1970s, tamizdat gradually became the most important source for obtaining longer works of literature.53 Samizdat and print culture were thus tightly enmeshed and interdependent. A comparison between them is fruitful for the task of identifying the special characteristics of the samizdat reader.

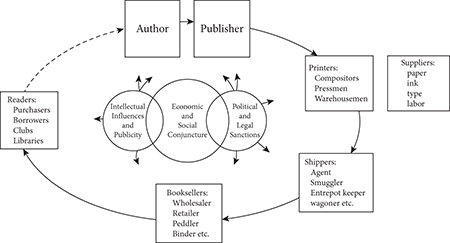

Figure 1, the ‘Communications Circuit’ diagram devised by Robert Darnton will illustrate and help us to understand the magnitude of the technical differences between print culture and samizdat.54

Figure 1 The Communication Circuit.

Source: Robert Darnton, ‘What Is the History of Books?’, Daedalus 111, no. 3 (1982): 68.

The diagram shows just how many intermediaries and influencing factors are habitually involved in a literary process. In this respect, neither Soviet official culture nor samizdat were exceptional. Yet in both processes the roles of intermediaries and external factors were distorted beyond recognition.55

Let us briefly first look at official culture, from which samizdat emerged and against which it reacted. The framework of Soviet official culture distorted, in particular, the three circles in the centre of the diagram. The need for all texts to be assessed by Glavlit, the censor’s office, to ensure their conformity with the ideological and aesthetic guidelines set by the Communist Party, and the central role of the Writers’ Union (which regulated who was considered a writer) both show that political sanctions played a disproportionally large role. These did not merely dwarf intellectual considerations; they were superimposed onto them. By contrast, market pressures as they were experienced in the West were largely suppressed. While Soviet publishing houses were in theory supposed to support themselves financially, the need to meet ideological and/or educational requirements usually overrode concerns for profit; readers were seen as receivers of culture rather than consumers of books.56

One could say that samizdat reacted to this imbalance by abolishing political (and legal) considerations altogether. The texts circulating in samizdat included anything proscribed by official culture, from erotica such as the Kama Sutra to poetry judged aesthetically deficient, religious texts, and material explicitly criticizing Soviet policy. Indeed, one of the definitions of samizdat literature is nepodtsenzurnaia literatura, literally ‘literature not under censorship’: that is, uncensored literature.57 Market pressures were virtually absent. Commercial samizdat was rare, although it became more common as time went on.58 Tamizdat books exposed unofficial publishing to political interests, some explicit, some indirect. At the same time, intellectual/aesthetic considerations were everything. In the absence of institutions such as libraries and bookshops, where a potential reader can familiarize themselves with a given text, a samizdat text had to find favour with its initial audience in order to gain even one additional reader.

The factors described above already indicate the importance of the reader and their taste above all else. However, samizdat’s greatest distortion of the communications circuit concerns the outer circle of the diagram and the roles described in each individual square. All these functions, from the decision to publish in the first place to printing, shipping/distributing, selling, binding and stocking, and preserving for posterity were carried out by the reader. Incidentally, this reader might also be the author of a text, in which case they would be responsible for the entire circle; as veteran dissident Vladimir Bukovsky remarked: ‘I write it myself, I edit it myself, I censor it myself, I publish it myself, I circulate it myself and I myself serve the prison sentence for it.’59 The typewriter as a method of production and the absence of an editorial process (unless we are talking about journals) meant that the threshold for becoming a ‘published’ author was low. Twenty-two respondents to the samizdat reader survey report that they were samizdat authors.

Most importantly, the readers were responsible for circulating a very limited number of physical copies to the largest possible circle of readers. Many of them produced further physical copies, either solely for their own use or for others; the typewriter made it possible to do both things at once. Consequently, the reader acted as both publisher and printer. Alexander Daniel maintains that this ‘secondary multiplication’ at one remove from the author’s own circle was instrumental to the process of samizdat.60 Irina Tsurkova, a typist who, among many other texts, also typed a short-lived journal called Perspektiva, identified this ability of the samizdat text to ‘live its own life’ as its most important feature, actively sought by samizdat authors:

However, samizdat had a special feature, which is why it was called samizdat, self-published – it was able to multiply by itself [samorazumnozhatsia]. A certain number of these twenty-four copies [the initial print run of the journal] were intercepted by the KGB; of course, some were thrown away, burnt or flushed down the toilet by people who took fright because they were being followed … On the other hand, you would pass a copy on to somebody, and that person would reproduce it, either by typing it out again or by making photocopies. This was very important. People would photograph the text, making it possible to print from the film … What was important was that these copies were alive – they were living a life of their own.61

Secondary copies were produced in great haste, as readers often kept texts for a day or a night only and during this short time typed up all or part of it. These material and temporal constraints were a major factor limiting the reach of samizdat texts, unlike in a book economy that can mass-produce copies and where circulation is determined by economic considerations such as production costs and level of reader interest. Naturally, the way in which copies were reproduced had a major impact on the state of the text as a physical object. Different copies of one and the same text often display an astonishing degree of variation, beyond obvious typos or accidental omissions. Unlike printed texts, typescripts could be, and regularly were, corrected by hand: for example, when words in Latin script had to be added.62 This practice blurs the distinction between manuscript and typescript, placing typescript somewhere in the middle between manuscript, where each copy is unique, and print, where technology ensures that all copies are identical. Moreover, the informal way in which these texts were reproduced changed the general understanding of a text as an inviolable whole. Readers took liberties with texts, making decisions that are normally the prerogative of authors or editors.63 Sometimes, people would copy out only part of a text or collection of poetry, to save time or for aesthetic reasons, and then circulate it, leading to a new version becoming established. One respondent to the samizdat reader survey reports cherishing handwritten copies of Akhmatova’s Requiem, a cycle of poems which circulated in samizdat for a long time and was also passed on orally, and then discovering that it did not correspond to the version that finally made it into print.64 In other cases, samizdat authors, translators or typists purposefully reproduced only part of a text. Natalia Trauberg, who translated, among other things, religious and philosophical texts from the English (Chesterton, C.S. Lewis), details how she would leave out large chunks of text she deemed inaccessible to her potential readers because they lacked the theological knowledge necessary to appreciate it.65 Elena Rusakova, a samizdat typist, gives another reason why longer texts were often incomplete: ‘I was typing [Andrei Platonov’s novel] Kotlovan [The Foundation Pit], and I was copying from a Western edition … In fact I wasn’t typing out the whole novel, because as usual, these books had to be returned quickly and we only had parts of it. So, I was typing out some parts, while somebody else did some others.’66The readers felt this effect, too. One survey respondent remembers that incomplete texts were a regular occurrence:

Samizdat is a printed text created by an underground press rather than an official one. As a rule, texts that were banned on the territory of the Soviet Union were published in this way. The texts were printed with the help of a typewriter on poor-quality paper. Books weren’t always complete – it happened that you would get part of a book and needed to wait for the next bit.67

Tamizdat books were read and reproduced in the same way, under extreme time pressure, with all the consequences that have been outlined above. This and the fact that many readers, including the majority of respondents to our survey, did not strictly distinguish between them justifies the treatment of samizdat and tamizdat as essentially part of the same phenomenon: as texts produced, circulated and read outside the state’s monopoly on textual production. Tamizdat also throws light on a different concept of ‘original’ and ‘copy’. Professional print was not necessarily seen as more authoritative, as Viacheslav Igrunov’s observation regarding the Chronicle of Current Events illustrates: ‘And another particularity: when it comes to samizdat, the relationship between “copy” and “original” is very difficult. The Chronicle of Current Events typed out on a typewriter, is considered the original, while the foreign [i.e. printed] edition is the copy.’68

Samizdat knew no copyright; indeed, copyright would have been counterproductive to its mission. This means that the author lost control over the text the moment he or she ‘published’ it; this was the price for it reaching the reader.69 Samizdat thus challenged the ‘Gutenberg model’ that was established when print made it possible to infinitely reproduce identical physical copies of a text. This paradigm presupposes that the text is fixed and has been created by one or several individually known authors, and that it is the author or authors who have ultimate responsibility for the text.70 The alterations made to samizdat texts during spontaneous reproduction – conscious or not – challenge this model; observers and scholars have used terms included ‘pre-Gutenberg phenomenon’,71 ‘extra-Gutenberg phenomenon’72 and ‘prä-printium’73 to describe the relationship between samizdat and established print culture. The difficulty in establishing the authoritative version of a given text naturally shifts the focus from questions of textual authority to those of dissemination and readership.74

It follows that individual copies of a given journal and their digital reproductions should be treated like archival relics rather than copies of an authoritative text; digital reproductions should indicate which archive or collection holds the particular copy that is being reproduced. The handmade, improvised and almost deliberately shabby appearance of samizdat texts has become their trademark sign and is now being studied extensively.75 At the same time there can be no doubt that the fluidity of samizdat texts was an accidental consequence of their material reality rather than the result of any deliberate action. Authors and editors actively strove for more durable formats to make the process less labour-intensive and ensure wider circulation. Tamizdat via émigré publishing houses can be seen as one such example. Copies smuggled abroad for publication and safekeeping in archives often became the authoritative version of a given text.76 Longer texts were increasingly reproduced with the help of photography and, later, copying machines. Journal editors, too, began to use copying machines as soon as it became possible.77 One side-effect of the emergence of authoritative versions was the loss of the individual samizdat script as a unique artefact. The modes of reproduction are discussed in detail in the subsequent chapters.

The processes described and examples given above demonstrate clearly the degree to which samizdat depended on the reader’s approval for its very existence in the most direct, physical sense, blurring the line between creator and receiver, in some cases consumer, of a medium. Yet readers can fulfil the tasks usually carried out by an army of professionals only to a limited degree, and the result, including the material available to the researcher, looks very different from the picture we know from mainstream literary culture.

Networks

Samizdat and the internet

Samizdat preceded the contemporary challenge presented to the ‘Gutenberg model’ by the internet. It has become popular to compare samizdat to the World Wide Web, particularly to social media. The Russian term for social media – sotsial’nye seti – literally translates as ‘social webs/networks’ and is also used to describe networks of people; this coincidence invites and facilitates the comparison.78 Articles on this topic regularly find entry into new volumes on samizdat.79 The well-known German journal Osteuropa (Eastern Europe) posits samizdat and the internet as spaces that allow the free word to flourish.80 Eugene Gorny, a leading expert on the Russian internet, has researched the significance of samizdat as one of the main metaphors used to describe the Russian section of the internet.81 Sharon Balazs has drawn up a useful table for comparing historical samizdat and the internet.82 Some very new research even compares the practice of file sharing to samizdat.83 There are less enthusiastic voices, too. Henrike Schmidt, who has written widely on samizdat and the internet, warns against a facile equation between the two phenomena. Her essay ‘Postprintium’ – a synthesis of a rich body of research, including from Russia – posits that the comparison only holds in certain particular cases, if we consider ‘samizdat’ to be a metaphor for describing a space where debate is relatively spontaneous, easily accessible to those who wish to contribute, and largely free of commercial interests.84 Comparing and contrasting samizdat networks and social media is not the purpose of this study. However, given that most of us use the internet every day, while only few have experience of samizdat, a brief consideration of certain points throws into sharp relief the particularities of samizdat and enhances our understanding of its reading, production and social environment.

The comparison usually hinges on the observation that both phenomena allow for the spontaneous generation of texts at grassroots level, without the interference of either editors or censors. Indeed, both samizdat and social media are based on network structures that are informal, fluid and capable of overlapping infinitely. On social media, users/readers can generate and circulate their own texts/content, while sharing and re-posting other people’s content can be construed as an analogue to the retyping of samizdat. Moreover, texts circulated on the web are not ‘fixed’ in the way printed texts are; readers who share texts can and do edit, alter and abridge them. As we have seen, the same happened to samizdat texts, although for different reasons. Naturally, the limits of the comparison become clear once we begin to consider these analogies in finer detail. First and foremost there are the constraints of laborious manual reproduction, which mean that samizdat remained a scarce and therefore highly coveted commodity, while texts on the web can – and do – become ‘viral’ with minimal effort. In the case of samizdat, these constraints also acted as a natural mechanism of quality control, and it is safe to assume that the majority of today’s social media posts would not have warranted the effort required to turn them into physical documents. Moreover, the way in which social media has changed our way of interacting with each other, introduced a habit of reducing important thoughts to sound bites, and possibly even influenced the way our brains are wired cannot easily be compared to the effect of samizdat on Soviet society.

However, the two differences between samizdat and the internet/social media that are relevant for the purpose of this study lie elsewhere. Firstly, the main issue facing the researcher who is trying to reconstruct the trajectory of samizdat texts – and thus the network of people reading them – is the lack of records. Spontaneous and illegal as it was, the samizdat process concealed the links between the origin of a text and its reader, as well as between readers sharing texts. By contrast, the internet, and social media in particular, render these links transparent. Online, the processes of reading and distribution become visible in the literal sense of the word: if not to the user themselves, then certainly to platform hosts, providers and specialists. There are also special platforms that enable users to display to each other what they are reading, recording engagement with a written text beyond mere possession.85 Reading samizdat would have been impossible without friendship ties and personal acquaintance. While social media can be used to stay in touch across continents, facilitate new contacts and organize large-scale events, they also have an isolating effect. Social media users do not need any other social media users around them in order to indulge – a smartphone and phone signal are all that is required. By contrast, reading samizdat brought people together and created communities, not only because connections were required in order to obtain samizdat but also because people often read rare texts collectively. Leonid Zhmud’ remembers: ‘This literature not only formed my political worldview but also determined my social circle, connecting me with many interesting people; the exchange of books was followed by an exchange of ideas.’86

Research into the digital sphere yields valuable insights into the structure of networks, and some of these insights can be applied fruitfully to samizdat. Samizdat as a whole was a network phenomenon that depended on multiple overlapping networks. Researchers of internet governance, for example, point out that – unlike traditional media – the ‘decentred network’ that is the internet has no single point of control and is therefore hard to regulate. The result is a broader network of networks as ‘communities gravitate towards other communities that share similar values’.87 A similar kind of ‘network individualism’ and lack of central control is precisely what made samizdat so lively and robust; the authorities were never able to suppress it. The mechanism of communities (groups, friendship networks) to enmesh with and influence each other will become obvious in the discussion below.

An alternative to official culture?

Samizdat networks were heterogeneous groups with fluid, informal membership. Situated outside official Soviet culture, they were nevertheless part of the cultural landscape, especially once the practice of reading samizdat became widespread among intellectuals. Participation in one or several samizdat networks did not require a person to renounce participation in official life – for example, by exercising a profession, including in the field of culture – or in other informal networks, such as blat, the complicated system of mutual favours, at work and elsewhere. One of the best-known conceptualizations of communities whose identity depended on being ‘inside-yet-outside’ authoritative discourse is that by Aleksei Yurchak; his analysis is not specific to samizdat groups, although most of his protagonists would have read samizdat. Yurchak’s conclusions are nevertheless helpful, as he examines the late Soviet generation’s ability to ‘[be] simultaneously inside and outside of some context – such as being within a context while remaining oblivious of it, imagining yourself elsewhere, or being inside your own mind. It may also mean being simultaneously a part of the system and yet not following certain of its parameters’.88 Crucially, Yurchak’s study includes groups that were close to Soviet institutions – for example, the Komsomol, the communist youth league – as well as those that were nominally outside all these structures, such as the regulars at the cafes that proliferated in Leningrad in the 1960s, including the famous Saigon.89 In a recent study, Ilya Kukulin criticizes as simplistic Yurchak’s conception of late Soviet networks. According to Kukulin, presenting these groups without recourse to social network theory fails to account sufficiently for their heterogeneity.90 Kukulin’s observations are certainly pertinent. However, Yurchak’s findings remain relevant to this study: not only does he emphasize the ambivalent relationship between official discourse and those who position themselves outside of it, but he also demonstrates how official social structures – the Palace of Pioneers, Literary Associations – could become spaces that allowed people, in particular young people, to develop a sense that they were situating themselves outside official discourse.91 The attitude of many samizdat readers towards official culture can be summarized, in the words of Natalia Pervukhina, as ‘our passive rejection’:92 underlining that, while people were willing to read forbidden literature and engage in lengthy debates in friends’ kitchens, for the majority of them this represented an internal attitude rather than a call to action. This emphasizes the low threshold required to become involved in samizdat. Even mere ‘passive dislike’ carried the seed of outsiderdom, as the fates discussed in my study demonstrate.

Yurchak and Kukulin are not the only researchers to focus on the ambivalent social location of samizdat networks. A positive and versatile appraisal is offered by Ann Komaromi. In her article ‘Samizdat and Soviet Dissident Publics’, Komaromi describes unofficial groups centred on samizdat reading with the help of Nancy Fraser’s concept of ‘counterpublic’, underscoring what she calls the ‘dialectic orientation’ of such groups. Her central argument is that samizdat groups operated in two spaces simultaneously, one essentially private and the other public. The private element – ‘space for withdrawing and regrouping’ – is easy to see. Whether or not a person was able to read (much) samizdat depended on their social environment: that is, the people they knew and the circles in which they moved. Samizdat also became currency in certain social networks. Irina Tsurkova described this phenomenon as follows: ‘I was almost always typing something, for my own enjoyment and in order to give pleasure to my friends - for example, in order to be able to give a splendid birthday present. In my circles it was considered very cool to be given a collection of samizdat for your birthday.’93 At the same time, the practice of samizdat generated new friendship networks, bringing people together on the basis of shared reading interests.94 The public element identified by Komaromi, the groups’ ‘function as training grounds for agitation directed against a wider public’, needs more qualification. Komaromi’s argument is based on two case studies: Soviet Jews as a national minority and the Leningrad feminists of the late 1970s. These groups were much more closely delineated than the friendship networks invoked by Tsurkova; they were also explicitly socially and politically active. Many Soviet Jews were lobbying for the right to emigrate to Israel, agitating against official Soviet policy which marginalized them. The underground feminists were agitating against patriarchal norms dominating, among other spheres, the male-dominated literary underground. It might be difficult to see how Komaromi’s definition could be applied to a loose friendship group exchanging poetry. However, her use of the term ‘agitation’ is not to be understood literally. Komaromi herself posits that cultural samizdat ‘functions as a laboratory of values and identities, new and alternative ways of defining the subjectivity that public activity aims to defend’.95 ‘New subjectivity’ is a category that is hard to define and even harder to quantify, and the influence of alternative civil platforms on the course of history remains contentious. However, the respondents to the reader survey confirm that samizdat reading fostered a new sense of identity, with more than a few suggesting that the ways of thinking honed by samizdat reading had some degree of impact on the demise of the Soviet Union. In this sense, samizdat groups represent counterpublics that were centred on an alternative form of media which, over the thirty-odd years of its existence, at the very least furthered a consciousness that was less influenced by Soviet official discourse.