Remembering Signorelli

If dreams are “the royal road to the unconscious”, Freud did not stumble upon this road straight away. His discovery of the unconscious came via another route: the unlooked-for byway of the talking cure. As Freud puts it in “The Question of Lay Analysis”, psychoanalysis seemed to stumble upon a modern confirmation of ancient beliefs in the magic power of words to effect changes in the real world (QLA: 187). To understand this chance discovery, Freud turned to the mechanistic biology pre-eminent in the culture of his time (Chapter 1) and his theory of the drives (Chapter 2). Yet the primary evidences upon which Freud based his theoretical conclusions remained linguistic: the spoken clinical testimony of analysands. When Freud asked his analysands to free-associate, phenomena emerged that seemed to point him away from the solely natural-scientific approach he desired. Instead, they recommended a primarily interpretive theory of the psyche (see Chapter 8). Analysands would recount their dreams, as if these were somehow connected to their malaises. Moreover, Freud’s analyses of neurotics’ symptoms pointed towards the specific importance of language in shaping neurotics’ symptoms, as well as their cure. We glimpsed this in Chapter 1, when we considered the strange symptom of the psychotic who felt her deceptive boyfriend had “twisted her eyes”, or the metaphorical “blood on Lady Macbeth’s hands”. The point can be illustrated further by returning to the Ratman case, and considering what might be in this name Freud bestowed upon him.

KEY POINT Why did Freud call the "Ratman" the "Ratman"? (Rat = Ratte = Spielratte)

As we saw in Chapter 1, the “Ratman” suffered from an obsessional neurosis manifested in compulsive symptoms. Why did Freud dub him the “Ratman”? Freud’s rationale comes from the young man’s “great compulsive fear” (RM: 165):

- This fear hailed from a story he had been told by a captain, while serving in the army. This captain, who “took pleasure in cruelty” (RM: 166), recounted an oriental punishment whose culmination was rats boring into the criminal’s anus.

This story is shocking enough. But its immediate effect on the Ratman was very peculiar:

- The cruel captain advised him that he was in debt to “Lieutenant A” for a small postal fee. Although our young man knew that this was not truly so, he immediately felt compelled to pay Lieutenant A anyway, lest the rat punishment happen to him.

How does Freud explain this bizarre symptom?

- The rat story provoked the young man’s unresolved Oedipal ambivalence towards his dead father (coupling rivalry towards him with anal eroticism, characteristic of the “passive” Oedipal complex (Chapter 2) ).

- The cruel officer recalled his father to the Ratman (his second association to the rat story was that the punishment should happen to his father), who had cruelly prohibited the young boy’s infantile sexual activities (principally, his masturbation).

- His father, who like the Ratman had been in the army, had once racked up a debt (“Ratte”) in a game called “Spielratte” (gambling debt); and our young man also suspected that his father had acquired syphilis (through sexual misdemeanours) during his time in the military.

Freud thus contends that in his unconscious the young man “inaugurated his own rat currency” (rat = Ratte = Spielratte) around which his symptoms turned. In reaction against the repressed wishes provoked by the cruel captain’s rat story, the Ratman identified with his dead father, taking on absurdly a proxy of his father’s Spielratte debt (Ratte) as reparation for his own criminal impulses (“you will be a great man or a great criminal”, his father had once opined) (RM: 205), lest the anal rat punishment happen to him.

How was Freud to account for such phenomena, with their apparently linguistic character? Given Freud’s metapsychological apparatus, already discussed, the answer might seem clear enough. Consider, for example, another of the evidences Freud encountered in the clinic, the famous “Freudian slips” or “parapraxes” (“practices beside themselves”), like that of the man described in The Psychopathology of Everyday Life who says “I hereby declare this meeting closed” when his conscious, professional role was to open it (PEL: 59). Here, as in neurotics’ compromise formations, the man’s illicit wish to be done with the whole affair has put egg on his ego’s face. Yet this explanation defers the deeper question, of how such an illicit wish could trouble this subject’s speech at all. According to long-standing philosophical and cultural precedents, words are “higher things” – the bearers of intellect, soul and spirituality. Yet the drives Freud associates with the unconscious are anything but spiritual, when they are not evil. As we commented in the Introduction, in the modern culture Freud inherited, these older dichotomies (body–mind/spirit) were reflected in the disciplinary division between the natural sciences and the interpretive human sciences. The symptomatic challenge Freud’s clinical discoveries posed to these inherited oppositions emerges further when we examine another famous case from The Psychopathology of Everyday Life: Freud’s own “chance” forgetting of a proper name on a train ride to Herzogovina. While on this journey in 1898, Freud forgot the name of a painter who painted frescoes of “The Four Last Things”. Although the correct name was on the “tip of his tongue”, Freud could recall only the names Botticelli and Boltraffio. What did Freud’s free associations on this matter reveal?

KEY POINT Why did Freud forget "Signorelli"? (PEL: 1–7)

- Freud had been talking to his companion about the customs of the Turks living in Bosnia and Herzogovina. Freud was (favourably) struck by the confidence the locals placed in their physicians, even when the doctor was forced to convey the very worst: “Herr [sir], what is there to be said? If he could have been saved, I know you would have saved him . . .”

- This thought about death was connected in Freud’s mind with another thought that Freud tells us that he, consciously, did not want to pursue: the great importance the Turks place on sexual health, so one had said to a colleague: “Herr, you must know that if that comes to an end then life is of no value.”

- This thought reminded Freud of the news he had heard in Trafoi about a patient of his who had committed suicide because of a sexual disorder.

So, Freud argues, his forgetting of Signorelli was not senseless, but revealed the activity of his unconscious. The final motive concerned this last, dead patient and sexuality. Yet, as in a symptom, this motive was not all that was repressed – what was lost to his consciousness was the name of a painter, albeit one who painted a fresco about such “last things”. Why?

- The vital thing is that the name “Signorelli” was repressed because it had become “placed” in an “associative” linguistic “chain” with this repressed thought. It concerned the syllables in the word “Signorelli”, in particular “Signor”, the Spanish equivalent of “Herr” (“Mister” or “Sir”). In Freud’s associations, this “Signor” evoked the sayings of the local patients: “Herr, you must know . . .” which so troubled him, since they recalled the suicide of his patient. Because “Signorelli” was thus so closely linked to the repressed, Freud says that it had been “drawn down” into the unconscious and forgotten.

- Yet the repressed returned in substitutive linguistic forms. The “Herr” invoked in “Signor-elli” was associated with “Her-zogovina”, and thus Bosnia. Hence the two names that Freud could recall shared the first syllable “Bo-” with “Bosnia”: “Bo-tticelli” and “Bo-ltraffio”. The first name, “Bottic-elli”, shares the “-elli” suffix with the forgotten “Signor-elli”. The second, “Bol-traffio”, evoked “Trafoi”, in turn indirectly connected in Freud’s mind with the repressed thought, because this was where he heard the bad news about his dead patient.

Hence, pictorially:

Freud's topographical account of the psyche

Freud’s account of the vicissitudes of the drives allows him to explain how many symptoms (for example, obsessionals’ compulsions) are the indirect expressions of repressed drives. Yet none of these vicissitudes (reversal of aim, turning around of object upon the ego, repression, aim-inhibition and so on) can help us with this case of Freud’s forgetting of “Signorelli”. For what Freud’s analysis of this case supposes is that people’s repressed sexual or aggressive drives are “caught up” in the linguistic formulations of their memories and self-understandings. When these drives are formed, Freud’s analysis suggests, they become “associated” with certain words, such as “Trafoi” or “Herr, if that is ended . . .”. These word-representatives of the drive(s), in turn, have different kinds of relations in the person’s mind with other words (e.g. “Herzogovina”, “Boltraffio” and so on). Some of these relations are rational, but others are less clearly so: like relations based on sound (“Herr” and “Her-”, “Boltraffio” and “Trafoi”); or on meanings across different languages (“Signor” and “Herr”); or the common place these words have in otherwise unrelated, but personally significant, sentences (“Herr” in both “...what is to be said...” and “...if that is ended”). The key to Freud’s analysis is that – in what he calls secondary repression (as opposed to the “primal repression” of the illicit sexual and aggressive wishes themselves) – many of these associated ideas, like the innocent name “Signorelli”, are accordingly repressed by the individual. They become guilty by association. In our example, only “Botticelli” and “Boltraffio” were sufficiently distant from the repressed chain of words that they could reach Freud’s conscious mind in place of the forgotten “Signorelli”.

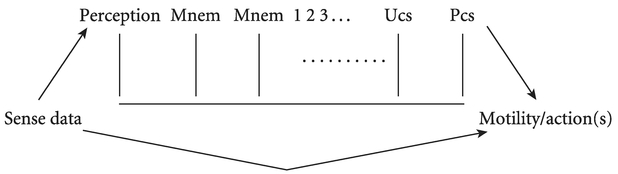

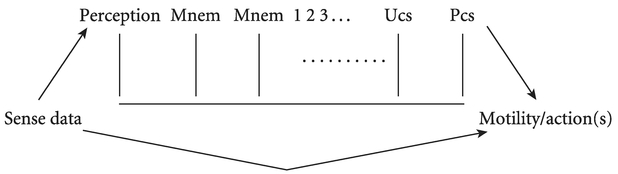

In Chapter 7 of The Interpretation of Dreams, reflecting on these types of analytic phenomena, Freud develops a “topographical” account of the psyche, different from the biologically based account of the psyche we have examined in Chapters 1 and 2. Drawing on ideas first developed in correspondence with his friend Fliess, Freud argues that the psyche is a kind of “mnemic” (remembering) apparatus. This apparatus has two functions. The first function, associated with “the system perception-consciousness”, is the ability to perceive new things in the changing external world. This function is connected with the “access to motility”: the individual’s ability to fight, flee, or pursue what it perceives. The second function, equally crucial to the operation of the reality principle and the individual’s maturation, is to record in memory significant aspects of the external world so that the ego might avoid painful and experience pleasurable things in future (Chapter 1). There are a host of things a person at any one time will be able to remember by simply redirecting their conscious attention: for example, what they had for breakfast, their pet’s name, job, stock prices and so on. Freud calls these things preconscious (he abbreviates this to Pcs). They are generally “filed” in ways we recognize as rational: according to the rules of logic and of the linguistic community we live in, or – in the case of experiences – according to rational considerations such as when and with whom we experienced them.

Figure 3.1 Freud’s topographical model of the psyche (ID: 537)

How then does the unconscious enter Freud’s “topographical” model of the psyche? Freud’s claim is that everything we experience simultaneously leaves a variety of “records” or “Mnems” in the psyche:

The first of these Mnem. systems will naturally contain the record of association in respect of simultaneity in time; while the same perceptual material will be arranged in later systems in respect to other kinds of coincidence; so that one of the later spheres, for instance, will record relations of coincidence; and so on with the others ...

(ID: 539)

Freud asks us to picture the mind, on this basis, as shown in Figure 3.1. The sweeping arrow in the diagram below the mnemic systems indicates the course taken by a perception that produces an immediate action: say, fleeing a threat. We perceive the threat (on the left) and act immediately (on the far right). The “Mnem”, “Mnem 1”, “Mnem 2” . . . lines signify the different ways in which the perception (let us say it is a snake) will be classified in memory, in terms of: how it looked, when we saw it, where, how, with whom, and so on. Freud’s argument is that the same perception of the snake of our example will be “filed” in a number of mnemic systems, according to: when it was seen, what it looked like (snake, lizard, pole . . .), who we were with when we saw it, how it affected us, but also according to the words that share linguistic features with the word that describes it (snake–rake–cake...sn ake– snag–snack...etc.).

So note that the unconscious (Ucs), in this topographical Freudian model, is one such mnemic system. Located on the right-hand side of the diagram, it guards access to the preconscious, and with it, access to the sources of motility. The preconscious carries “word-presentations”, Freud specifies: “the conscious presentation comprises the presentation of the thing plus the presentation of the word belonging to it”. The unconscious, by contrast, is a mnemic system that contains “presentation of the things alone” (Ucs: 201–2). Freud’s idea is that, when an idea is repressed, the preconscious cathexes of energy are withdrawn from it, and with them, their rational or logical links with other ideas. The unconscious accordingly involves an unholy confusion of tongues, arranging words-presentations as if they were things – not according to rational rules or considerations, but like a bad poet, according to how they sound. This is why analysands themselves cannot understand the meaning of their symptoms, and why Freud could not at first remember “Signorelli”. This name had been severed from its rational links with other ideas (like “the painter who painted the ‘Last Things’”) on grounds of its phonic associations (Herr → Signorelli) with the representatives of repressed wishes.

KEY POINT The five special characteristics of the system-Ucs, or "primary process" thinking (Ucs: 186–8)

Freud contrasts the “primary process” thinking characteristic of the system-Ucs with the “secondary process”, rational thought (mostly) characteristic of the system-Pcs.

- The representatives (Vorstellungen) of repressed drives, cut free of rational, logical links, are independent of each other. They exist side-by-side in the individual’s unconscious and can be logically contradictory. While one cannot rationally wish for both A and not-A, as philosophers underline, in the unconscious we do this all the time.

- There is no negation, nor any degree of doubt in the system-Ucs. As we shall suggest in Chapter 5, negation is a more advanced mental process to deal with things with which the psyche “disagrees” than the type of thinking characterizing the system-Ucs.

- The energy that is “cathected” or “bound” to drive-representatives in the unconscious is much more mobile than that attached to preconscious ideas. (We shall return to the two mechanisms Freud specifies here about how the quantities of affect can move around: displacement and condensation.)

- The processes of the unconscious are timeless. The memories or drive-representatives are not ordered rationally in this temporal sense either: things remembered from yesterday can be linked in the unconscious mind with events that occurred in the individual’s childhood. Nor does the passage of time age these earlier memories: “they have no reference to time at all” (Ucs: 187).

- The system-Ucs lacks any ability to distinguish representations of internal/psychical ideas and outside reality – as in early infancy and also in the process of repression. Insulated from reality testing, “their fate depends only on how strong they are and on whether they fulfill the demands of the pleasure–unpleasure regulation” (ibid.).

For all the apparent differences between Freud’s topographical and the dynamic biological account of the psyche we developed in Chapters 1 and 2, Freud always maintained that his two metapsychological perspectives were complementary. The reason is that each of the interpretable mnemic representatives of our external experiences and internal drives carries with it a quantity of “cathected” energy. A correct psychoanalytic interpretation releases the energy bound up with some repressed memories or idea(s). This is how Freud thinks that we can explain the central mystery of the psychoanalytic clinic: how an act of speech can produce effects on the analysand’s body and psyche, dissolving her symptoms. Psychoanalysis as the practice of interpreting the unconscious, if Freud is right, is accordingly a practice located somewhere between hermeneutics and the natural sciences, in a way that has caused philosophers continuing epistemological problems (see Chapter 8).

With both the dynamic and topographical perspectives on the unconscious in place, we are now in a position to travel directly down Freud’s royal road.

. . . Perchance to dream

The dynamic account of dreams as the fulfilment of wishes

Freud’s account of dreams is among the richest but most difficult parts of his oeuvre. The basis of his account is typically clear and distinct. “The meaning of every dream is the fulfillment of a wish ... there cannot be any dreams but wishful dreams,” Freud announces in The Interpretation of Dreams, after surveying and critiquing earlier religious and philosophical views (ID: 134). Dreams do not predict the future, nor do they give us direct insight into the “other world”, as many of these views maintain. When looking at the contents of a dream, Freud proposes, we should effectively simply “prepend” to these contents: “I wish that ... [dream contents a, b, c ...].” Consider the dreams of small children. Freud recounts how a child who, during the day, was denied her wish to eat strawberry cake, dreamt that night of savouring the most delicious cake. It does not take a contemporary Joseph to see that this dream provided the young girl with a substitute satisfaction, like a symptom. But Freud’s interpretation goes further. Recall from Freud’s account of earliest infancy in Chapter 1 his claim that children from very early on hallucinate fulfilments of their wishes. Sleep itself represents an approximation to reactivation of interuterine existence, Freud claims (MSD: 222). Our dreaming activity, he maintains, is a regressive reactivation of the hallucinatory means of “wish-fulfilment” of these first days, unchecked by the reality principle.

Having stated the thesis that dreams stage the hallucinatory fulfilments of wishes in The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud immediately recognizes: “I feel certain in advance that I shall meet with the most categorical contradictions” (ID: 134). One objection that was to trouble Freud throughout his career is that people have nightmares or “anxiety dreams”. These cases seem deeply opposed to any idea that dreams fulfil wishes. Although in “Beyond the Pleasure Principle” Freud later hesitated on this (see Chapter 4), in The Interpretation of Dreams he argues that anxiety dreams in no way contradict what his theory would lead us to expect. Recall how Freud’s metapsychology is built around the postulate that human beings have competing wishes, and that many of these wishes – principally infantile sexual or aggressive wishes – contradict the individual’s reality-testing, moral self-image. The drives that an individual represses are those drives the attainment of whose aim would produce pain instead of pleasure. Anxiety dreams in this light become intelligible as dreams that stage too directly the satisfaction of transgressive unconscious wishes. The ego, whose defences against the id are lulled when the person falls asleep, eventually responds to the hallucinated fulfilment of the id’s wishes in the dream as if responding to a real, external threat. When the resulting anxiety becomes overwhelming, the sleeper indeed wakes to avoid the perceived danger (ID: 556–7, 580–85).

As we saw in Chapter 1, Freud argues that even to pay wakeful attention to the outside world requires all the psychical effort involved in reality-testing. At its most basic, then, sleep for Freud is the periodic withdrawal of this psychical effort of attention, so “the batteries can be recharged”. As the case of sleepers being forced to wake by anxiety dreams indicates, so Freud contends that the most basic wish at play in our dreaming activity is simply the wish to continue sleeping. We can see this also in cases where some external interruption (e.g. the sound of one’s alarm clock) is more or less instantaneously woven into our dreams (as, say, a church bell, school bell, part of a movie, etc.), so we can continue sleeping. However, if the aim of the wish to sleep is to wholly withdraw our “cathexes” from our daily concerns, why do we dream at all? Why isn’t all sleep dreamless sleep? Well, for Freud, the fact that we do dream attests that the organic wish to wholly “shut down” stands arrayed against other wishes in the psyche that refuse to be wholly silenced when we go to sleep.

Freud specifies two types of wishes that conspire against a night of undisturbed, dreamless sleep. The first are wishes we carry with us from the previous day or days, “the day’s residues”:

Observation shows that dreams are instigated by residues from the previous day: thought-cathexes which have not been submitted to the general withdrawal of cathexis [to objects and concerns with external reality], but have retained in spite of it a certain amount of libidinal or other interest.

(MSD: 224)

These residues will be the types of thing that emerge more or less freely when analysands are asked in the clinic to free-associate regarding the various elements of their dreams (see below). Freud calls such chains of thought the “latent contents” of our dreams, in contrast to their “manifest contents”.

KEY POINT The distinction between the latent contents and manifest contents of dreams

- The manifest content of a dream is what we experience as we sleep: usually a series of images that seem to form a coherent sequence, such as a movie – albeit one in which we are invariably the star.

- The latent content of a dream are the “dream thoughts” that underlie and inform the manifest dream contents. They can be uncovered by asking the dreamer, as in the clinic, what the various elements within the manifest contents “remind” them of.

In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud specifies that the day’s residues which inform the manifest contents of our dreams come particularly from wishes, concerns or chains of thought that have remained incomplete in the waking day. We might not all get as vexed as Freud’s child was that we cannot eat strawberry cake. But perhaps an important conversation was interrupted by chance. Or perhaps we have been obliged to “sleep on” some unresolved work or personal problem. It is from the broken fabric of such interrupted events that the manifest content of dreams is woven (ID: 551–2, 554).

The second type of wish involved in our dreams, Freud however stresses, is unconscious wishes – the types of wish that will not emerge instantly in the clinic. Freud hypothesizes that, however vexing the dream day’s unfinished business, by itself it will not be sufficient to overcome the general shutting down of the psychical apparatus involved in sleeping. If it is “to figure as constructors of dreams”, this unfinished business of the “dream day” must find “reinforcement which has its source in the unconscious...impulses” (MSD: 224). The day’s residues must form some “link” or “connection” with unconscious wishes that date from much earlier than the previous day (ibid.: 226). There is in this way a “temporal regression” involved in the construction of dreams. The manifest content of the dream will be the result of a kind of superimposition of the repressed unconscious wish with the unfulfilled, preconscious wishes of the dream day. In colloquial terms, two unfulfilled wishes are much better than one when it comes to the formation of dreams. Indeed, if the dream were solely the direct expression of a repressed unconscious wish, it would never make it into our conscious life, any more than a dream based solely on the day’s events. However weakened the ego’s vigilance against the id is when we sleep, it still maintains a “censorship” of our dreaming activities. This censorship is like the censorship political regimes exercise on the criminal actions or seditious statements of their subjects. Any too direct hallucinatory staging of the fulfilment of such wishes would hence be censored, just as it is the failure of the censorship that Freud argues leads to our having anxiety-provoking dreams (see above). Freud’s hypothesis is that, since we do dream, we must suppose that the manifest content of any dream is the result of the psyche having it both ways – the dream “gives expression to the unconscious impulse in the material of the previous day’s residues” (MSD: 226).

The topographical account of dreams: Freud's psychoanalytic theory

The second major objection facing Freud’s claim that all dreams are wish-fulfilments is that so many of adults’ dreams seem absurd – not signifying fulfilled wishes, but so much sound and fury. Surely the sleeping psyche is simply burning off energy, so that the products of this process have no rhyme or reason? Freud accepts the idea that the dreaming psyche is burning off energy. Yet he disputes the implication that the products of this “letting off of steam” have no meaning. In psychoanalysis, when an analysand “free-associates” on the manifest content of the dream, he claims, we very soon find that even the most apparently random products of a dreamer’s mind have manifold connections with their wider thoughts and concerns. Each dream has a plethora of “latent contents”, to use Freud’s technical term. Once we acknowledge this, the enigma posed by the manifest absurdity of dreams concerns the relations between the manifest content of the dream and the individual’s latent dream thoughts.

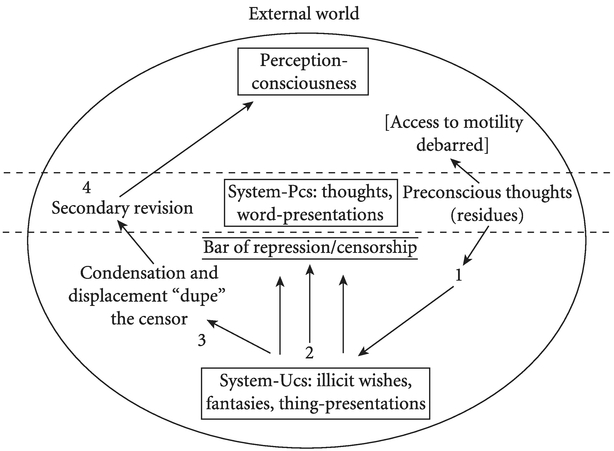

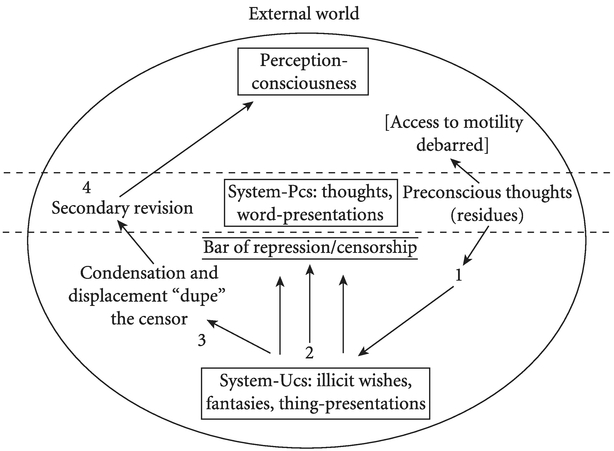

Figure 3.2 The metapsychology of dreams Notes:

1 The system-Pcs day’s residues are “drawn into” the system-Ucs.

2 Ucs wishes are “linked” to day’s residues to form the “dream wish”.

3 The dream work of condensation and displacement takes place.

4 Dream content becomes conscious as a hallucinated sense-perception.

When we examine these relations for any dream, Freud argues, it soon becomes clear that a complex process is involved in its construction. Freud calls this process the dream work. The dream work can be envisaged as in Figure 3.2, which can also form the basis of our understanding.

At point 1 of the process shown in Figure 3.2, the preconscious “day’s residues” are debarred access to motility, since the person is asleep. Instead, a link between them and the unconscious impulses is established, thanks to the easing of the communication between the Pcs and the Ucs associated with being asleep. This is a regression, Freud specifies, since the preconscious thoughts are rational, and expressible in sentences such as: “I wish that I had been able to solve that maths problem” or “I wish I had said more”, and so on. However, when the “text” of these thoughts (ID: 324, 388) is “drawn into” the unconscious, it takes on “the irrational character possessed by everything that is unconscious”. At this point, Freud contends, certain “considerations of representability” present themselves. These “considerations” follow from how the “text” of the rational Pcs chains of thought cannot all find “means of representation” in the more primitive system-Ucs (ID: 314). The dream thoughts, Freud specifies, “stand...in the most manifold logical relations to one another. They can represent foreground and background, digressions and illustrations, conditions, chains of evidence and counter-arguments...” (ID: 312). By contrast, we have seen that the system-Ucs contains the separate, a-logical “thing-presentations” tied to repressed wishes. Faced with the task of “translating” dream thoughts involving connectives such as “‘if’, ‘because’, ‘just as’, ‘although’, ‘either–or’, and all the other conjunctions without which we cannot understand sentences or speeches”, Freud argues that the system-Ucs simplifies this original text: “When the whole mass of these dream-thoughts is brought under the pressure of the dream-work...its elements are turned about, broken into fragments and jammed together – almost like pack ice . . .” (ibid.: 312). To describe this process, Freud asks us to imagine what a journalist would do if asked to reproduce a “political leading article” (ibid.: 340) wholly by means of illustrations – say, in a cartoon strip. First of all, they might scan their mind for concrete “figures of speech” that would allow the abstract ideas of the article to be presented pictorially. Every language has such “figures of speech”, Freud notes, which “in consequence of the history of their development, are richer in associations than [more abstract] conceptual ones” (ibid.). To describe how fine some politician’s rhetoric was, our political cartoonist might for instance evoke the “lofty heights” of his speech. The politician could then be depicted speaking on the heights of some mountain range, and the idea would have been successfully “translated” while respecting the relevant “considerations of representability”. In the same way, Freud argues that, in the formation of dreams:

A good part of the intermediate work done ... which se eks to reduce the dispersed dream-thoughts to the most succinct and unified expression possible, proceeds along the line of finding appropriate verbal transformations for the individual thoughts ...

(ID: 340)

So let us grant Freud that the nouns and verbs of the Pcs dream thoughts are in this way “packed into” more concrete figures of speech, wherever this can be done. Freud gives us many examples: a girl’s dream represented someone “hurling invectives” at her in the pictorial form of someone throwing a chimpanzee and a cat at her, making use of a German linguistic convention which “pictures” animals with invectives. A man’s dream represented his “being retrenched” by way of digging a trench in his garden. What though does Freud think happens to the logical relations between the things and actions the Pcs dream thoughts describe? How can these be pictured? Mostly, Freud argues, “it is only the substantive content of the dream-thoughts that [the Ucs] takes over and manipulates” (ID: 312). Nevertheless, the system-Ucs does use several primitive means available to it to try to represent higher-order logical connections between the preconscious dream thoughts. For example, a relationship of cause and effect can be represented in the dream work by the successive presentation of two wholly different scenes, or one dream figure transforming into another in front of our dreaming eyes; or the “distance” in time of an event represented in the dream can be represented by spatial distance – those people are now “so far away from us”, and so on.

As these examples show, the import of “considerations of representability” for understanding Freud’s interpretation of dreams can hardly be overstated. Dreams, for Freud, are distorted texts that, using “figures of speech” as a way of translating the linguistic dream thoughts, finally present themselves as sense-perceptions (at point 5 in Figure 3.2, “Perception-consciousness”) in a way that convinces the dreamer of their external, spatiotemporal reality. Freud for this reason opens Chapter VI on the dream work by comparing dreams to picture puzzles or rebuses:

Suppose I have a picture puzzle, a rebus, in front of me. It depicts a house with a boat on its roof, a single letter of the alphabet, the figure of a running man whose head has been conjured away, and so on. Now I might be misled into raising objections and declaring that the picture as a whole and its component parts are nonsensical. A boat has no business to be on the roof of a house, and a headless man cannot run ... But obviously we can only form a proper judgment of the rebus if we put aside criticisms such as these of the whole composition and its parts and if, instead, we try to replace each separate element by a syllable or word that can be presented by that element in some way or another . . .

(ID: 277–8)

We could not then be further mistaken than to imagine, as people often do, that dreams represent coherent narratives which unfold wholly at the sensory level, like a feature film. This is the principal reason why they seem manifestly absurd, like so many bad movies, or movies by David Lynch. Dreams are, in their way, coherent and meaningful products of the human psyche. Yet their coherence lies in the linguistic text of the dream wish, as it is pieced together out of the linguistic content provided by the Pcs dream thoughts. The sense we do sometimes get that the manifest pictorial contents of our dreams form a pictorial story Freud argues is a lure serving to lull the ego’s censorship. It represents the deceptive result of a kind of supplementary process concealing the dream but itself “not to be distinguished, [Freud] says, from our waking thoughts” (Lacan 2006: 426). This is “secondary revision” (point 4 in Figure 3.2).

KEY POINT What is secondary revision? (ID: 488–508)

Secondary revision is a final process of revision that hinders our waking ability to recollect, and interpret, our dreams. Secondary revision “fills up the gaps in the dream-structure with shreds and patches”. Its result is that “the dream loses its absurdity and disconnectedness and approximates to the model of an intelligible experience”, concealing in partcular its linguistic constitutuion (ID: 490). In Lacan’s gloss: “no better idea of this function’s effects can be given than comparing it to patches of color wash which, when applied here and there on a stencil, can make stick figures . . . in a rebus or hieroglyphics look more like a painting of people” (2006: 426).

So what then happens at points 2 and 3 of Figure 3.2? The “text” of the dream thoughts has been reduced to more concrete, pictorial figures of speech. But we are still far from the point at which the secondary revision repackages the elements of the dream into the semblance of a pictorial narrative. At point 2, Freud tells us, the dream wish is formed. This dream wish “gives expression to the unconscious impulse in the material of the preconscious day’s residues” (MSD: 226). In an important footnote added in 1926 towards the end of Chapter VI of The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud complained that people too often confuse the latent contents of the dream with its unconscious wish (note 2 at ID: 506–7). Nevertheless, as Slavoj AiBek has recently emphasized (AiBek 1989), the dream wish is not what a person will produce when asked to free-associate on the manifest elements of his dream. As with Freud’s famous dream of Irma’s injection, the latent thoughts will typically concern the person’s workaday life. In the dream of Irma’s injection, for instance, Freud’s preconscious wish was to be excused from culpability when his patient’s, Irma’s, health did not improve under his care (ID: 107–21). To use a metaphor, these preconscious wishes are for Freud instead like the materials the artist-unconscious has on its palette in order to make conscious its otherwise censored, illicit wishes. However, as in the “Signorelli” case, Freud emphasizes that these repressed dream wishes will always be of an infantile, sexual or aggressive nature, very different from the desire to “save face” in front of one’s colleagues, as in Freud’s Irma dream.

At point 3, with the dream wish having now “met” the pre-packaged, simplified dream thoughts, the psyche distorts or “transvalues” the dream thoughts to give indirect expression to this wish in a manner that further confounds the ego’s censorship. It does this through two processes, condensation and displacement.

KEY POINT Condensation and overdetermination

- When an analysand free-associates on the manifest contents of her dream, she will always produce quantitatively more thoughts than the number of manifest contents in the dream.

- These manifold latent thoughts, in order to make it into the dream, must accordingly be subject to a process of selection. In particular, only those elements that “link up” with more than one chain of latent dream thoughts will make it into the manifest content of a dream. Each of these “condensed” dream elements, Freud says, is overdetermined.

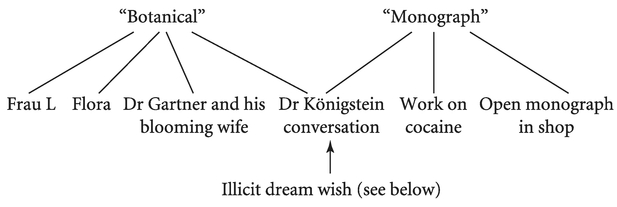

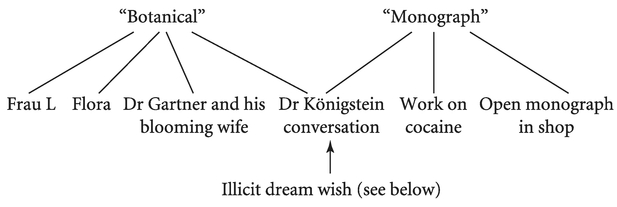

In order to illustrate condensation, consider Freud’s famous dream of the botanical monograph (ID: 282–4). The manifest content of the dream was this:

I had written a monograph on an (unspecified) genus of plant. The book lay before me and I was at the moment turning over a folded colored plate. Bound up in the copy there was a dried specimen of a plant.

What did Freud’s free associations reveal? First, resisting the lure of “secondary revision”, Freud divides the dream into its individual linguistic elements. He then associates on each of these in turn:

- “ monograph”: Freud had seen a “monograph” on a type of plant the day before in a bookshop. Moreover, “monograph” reminded Freud of his own monograph on cocaine, and of his friend Dr Königstein who had assisted the young Freud in his research for it. Freud had had a conversation with Dr Königstein the previous evening about the payment of medical services which, he confides, lay close to the illicit dream wish;

- “ botanical”: the word “botanical” recalled the name of Freud’s colleague Dr Gartner [Gardener], the “blooming” looks of Gartner’s wife which Freud had recently remarked, and to two of his analysands, one named “Flora” and a second [Frau L] to whom Freud had “told the story of the forgotten flowers” (the details of which do not concern us here).

Freud’s thoughts concerning Gartner recalled a conversation he had had with Dr Königstein in which Flora and Frau L had been mentioned. “Forgotten flowers” recalled to Freud’s mind his wife’s favourite flowers, and his own “jokingly” favourite flower, the artichoke. “Artichoke” then recalled to him an episode from his childhood “which was the opening of his own intimate relations with books [monographs]”.

Each of the dream elements, we can see, has “copious links with the majority of the dream-thoughts”. What such cases compel us to hypothesize, Freud says, is that

A dream is constructed ... by the whole mass of dream-thoughts being submitted to a sort of manipulative process in which those elements which have the most numerous and strongest supports acquire the right of entry into the dream-content – in a manner analogous to election by scrutin de liste.

(ID: 284)

Figure 3.3 The condensations in the “botanical monograph” dream

In the case of the dream of the “botanical monograph”, the work of condensation can be represented as in Figure 3.3.

Famously, alongside condensation, Freud lists displacement as a key mechanism of the dream work.

KEY POINT What is displacement? (ID: 306–9)

- Freud tells us that displacement is the “transference . . . of psychical intensities” between elements of the already-simplified dream thoughts. It illustrates the “mobility of cathexis” that Freud associates with the unconscious.

- The evidence that displacement has occurred in the dream work is that what psychoanalysis shows to be the most important dream thoughts (those closest to the unconscious wish) are completely unrelated to the events or actions that appear to be the most important in the manifest contents of a dream: “In the course of the formation of a dream these essential elements, charged . . . with intense interest, may be treated as though they were of small value, and their place be taken in the dream by other elements, of whose small value in the dream-thoughts there can be no question” (ID: 306).

The botanical monograph dream also illustrates what Freud means by “displacement”. Freud tells us that the dream thoughts all turned on his important conversation with Dr Königstein. This conversation, as he confides, had invoked illicit wishes he is not at liberty to disclose, given the censorship of his own times. Yet the manifest dream is about a botanical monograph, a folded plate and a dried specimen of plant! Nothing could seem further from any illicit sexual wishes, or even Freud’s conversation with Königstein. Displacement, Freud emphasizes, plays a particularly important role in the distortion of the unconscious dream wish. Since the latent content of the dream is in this way “displaced”, the dream wish whose fulfilment is being indirectly represented simply does not come to the attention of the censor, just as it usually completely eludes the sleeper on waking.

An illustration: the Wolfman's "primal scene" dream

Given the complexity of Freud’s understanding of the dream work, we close by considering one complete Freudian dream analysis. The dream in question comes from Freud’s psychoanalysis of “the Wolfman”. Alongside Little Hans and the Ratman (and Dora and Schreber, whom we have still to meet), the Wolfman analysis is one of Freud’s great case studies. As The Interpretation of Dreams puts it, this case history presents not only a psychoanalysis of the individual elements in the dream. Freud also performs a “synthetic” reconstruction of the dream, in light of the analysis’s full disclosure of the dreamer’s unconscious wishes.

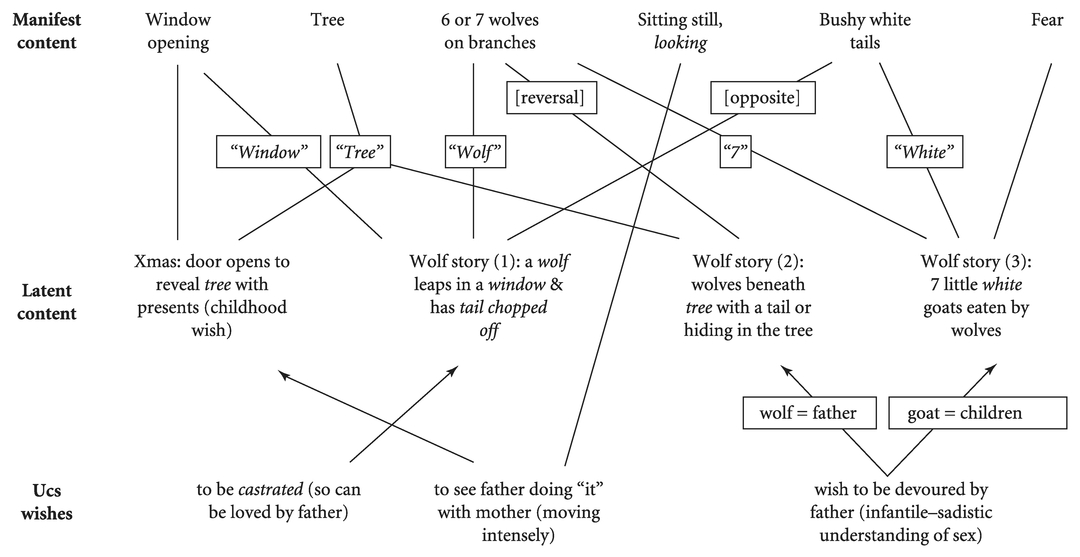

At the heart of the Wolfman’s analysis was a recurrent dream he had had over many years. The key elements of the manifest content of the dream were as follows:

Suddenly the window opened, outside of which was a large tree. The tree had many branches. 6 or 7 wolves were perched upon them. They were not moving. The wolves sat still, looking in through the window at the dreamer. They each had large white tails. The overwhelming affect of the dream was one of fear.

(cf. WM: 29)

Here, as elsewhere, Freud’s interpretation proceeds on the basis of the Wolfman’s free associations on each of the dream elements. These associations disclosed the “latent contents” of the dream: the dream thoughts. As the analysis bore out, these latent thoughts turned on two associative chains:

- a childhood memory of the door opening at Christmas time to reveal a tree with presents on the branches (WM: 35 – 6, note 2 at 42–3); and

- childhood fairytales that had made a strong impression on the Wolfman, about wolves who eat little goats, hide in trees, but who end by having their tails chopped off as punishment for their misdeeds (ibid.: 29–32, 41–2).

The Wolfman’s psychoanalysis revealed, however, that the unconscious dream wishes behind the dream concerned the analysand’s infantile sexuality, and in particular his unresolved Oedipus complex. Specifically, the Wolfman’s infantile sexual development was deeply affected, Freud contends, by his witnessing at a very young age the spectacle of his parents having sexual intercourse (WM: 36–8). Although he was too young to comprehend the spectacle (see Chapter 2), this event was to have a lastingly traumatic effect upon him as he matured sexually. The Wolfman’s sexual development suffered from a fixation at the anal phase. His own amorphous sexual wishes became fixated around a series of wishes characteristic of this infantile stage: the wishes to see his mother and father doing “it”, to be castrated (so his father might do it to him, according to the “passive” Oedipus complex), and to be devoured by his father (on the basis of a sadistic/oral understanding for which to love is equivalent to “gobbling up” the beloved).

Figure 3.4 shows how Freud understands the dream work in this case. The force of these repressed wishes distorted the Wolfman’s latent dream thoughts concerning the Christmas tree and the story so as to give rise, in their place, to the horrifying insistent dream of the wolves on their braches, gazing in fixedly at him.

Summary

- Freud couples his dynamic, biological account of the psyche with his “topographical” account. The topographical account sees the psyche as a “mnemic” (memory) device with two “systems”: the system-Pcs (containing rationally associated memories, ideas and “drive representatives”) and the system-Ucs (the unconscious). The unconscious is a mnemic system characterized by “primary process” thinking, in which “drive-representatives” are treated separately, as “thing-representatives” not subject to reality-testing, which may thus contradict each other, are timeless, and able to be linked, according to the most apparently tenuous links, with preconscious ideas.

- The royal road to understanding the primary processes of the system-Ucs is the interpretation of dreams. Freud’s account of the construction of dreams, based upon his contention that dreams always stage the fulfilment of wishes, brings together his dynamic and topographical accounts of the psyche.

- The preconscious dream thoughts, made up of the dream day’s cognitive “residues”, are “drawn into” the unconscious, then “sifted” into more concrete pictorial language. Hence their manifold logical relations are simplified into the types of relations that can hold between pictured things (considerations of representability).

- The dream wish then “links” with the unsatisfied preconscious wish from the dream day. This simplified “text” becomes the contents out of which this wish will form its indirect hallucinated satisfaction in the dream’s manifest contents.

- In the process of condensation, only those elements of the latent content connected to many (or most) of these latent thoughts make it into the manifest content of the dream. Because of displacement, by contrast, the elements seemingly central in this manifest content are generally not those that are most important in the original preconscious thoughts. The process of displacement highlights the distorting impact of the intersection of the repressed dream wish on the latent dream thoughts. In order to reach consciousness, this wish must “transvalue all [the] psychical values” from the day’s residues. In particular, the latent thoughts most closely connected to this illicit wish must themselves disappear from the manifest content, or be relegated to a seemingly incidental place in the dream.

- In the process of “secondary revision”, finally, the contents of the dream are given a last “once-over”, so the dream is made to appear as a coherent pictorial story capable of convincing the dreamer that its manifest contents are real, and he can continue sleeping.