Fig. 30.Fig. 31.Fig. 32.

THE BLAZONING OF ARMORIAL BEARINGS

In this chapter we shall deal with blazoning, in which "the skill of heraldry" is said to lie.

The word "blazon" in its heraldic sense means the art of describing armorial bearings in their proper terms and sequence.

"To blazon," says Guillim, "signifies properly the winding of a horn, but to blazon a coat of arms is to describe or proclaim the things borne upon it in their proper gestures and tinctures" (i.e., their colours and attitudes) "which the herald was bound to do."1

1: Our word "blast," as well as our verb "to blow," are obviously derived from the German blasen, the Anglo-Saxon blawen, to blow, and the French blasonner.

The herald, as we know, performed many different offices. It was his duty to carry messages between hostile armies, to marshal processions, to challenge to combat, to arrange the ceremonial at grand public functions, to settle questions of precedence, to identify the slain on the battle-field—this duty demanded an extensive knowledge of heraldry2—to announce his sovereign's commands, and, finally, to proclaim the armorial bearings and feats of arms of each knight as he entered the lists at a tournament.

2: Do you remember that in the "Canterbury Tales" the knight tells the story of how, after the battle, "two young knights were found lying side by side, each clad in his own arms," and how neither of them, though "not fully dead," was alive enough to say his own name, but by their coote-armure and by their gere the heraudes knew them well?

Probably because this last duty was preceded by a flourish or blast of trumpets, people learnt to associate the idea of blazoning with the proclamation of armorial bearings, and thus the term crept into heraldic language and signified the describing or depicting of all that belonged to a coat of arms.

The few and comparatively simple rules with regard to blazoning armorial bearings must be rigidly observed. They are the following:

1. In depicting a coat of arms we must always begin with the field.

2. Its tincture must be stated first, whether of metal or colour. This is such an invariable rule that the first word in the description of arms is always the tincture, the word "field" being so well understood that it is never mentioned. Thus, when the field of a shield is azure, the blazon begins "Az.," the charges being mentioned next, each one of these being named before its colour. Thus, we should blazon Fig. 44 "Or, raven proper." When the field is semé with small charges such as fleur-de-lys, it must be blazoned accordingly "semé of fleur-de-lys," in the case of cross-crosslets, the term "crusily" is used.

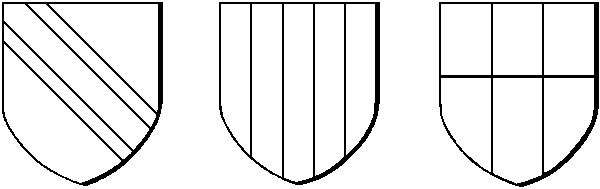

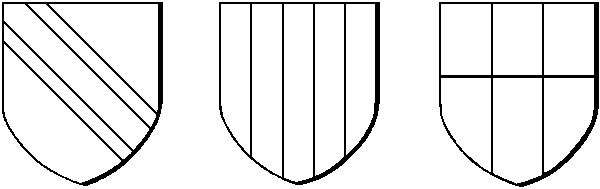

3. The ordinaries must be mentioned next, being blazoned before their colour. Thus, if a field is divided say, by bendlets (Fig. 30), the diminution of bend, it is blazoned "per bendlets," if by a pale (Fig. 18), "per pale," or "per pallets," if the diminutive occurs, as in Fig. 31, whilst the division in Fig. 32 should be blazoned "pale per fesse." The field of Fig. 17 is blazoned "arg., two bars gu." All the ordinaries and subordinaries are blazoned in this way except the chief, (Fig. 15), the quarter (blazoned "per cross or quarterly") the canton, the flanch, and the bordure. These, being considered less important than the other divisions, are never mentioned until all the rest of the shield has been described. Consequently, we should blazon Fig. 48 thus, "Arg., chevron gu., three soles hauriant—drinking, proper, with a bordure invected sa."

Fig. 30.Fig. 31.Fig. 32.

The term invected reminds us that so far we have only spoken of ordinaries which have straight unbroken outlines. But there are at least thirteen different ways in which the edge of an ordinary may vary from the straight line. Here, however, we can only mention the four best-known varieties, termed, respectively, engrailed, (Fig. 33, 1), invected (2), embattled (3), and indented (4). Other varieties are known as wavy, raguly, dancetté, dovetailed, nebuly, etc. Whenever any of these varieties occur, they must be blazoned before the tincture. Thus in describing the Shelley arms, Fig. 50, we should say: "Sa, fesse indented, whelks or." Fig. 34 shows a bend embattled, Fig. 35 a fesse engrailed.

Fig. 33.

Fig. 34.

Fig. 35.

4. The next thing to be blazoned is the principal charge on the field. If this does not happen to be one of the chief ordinaries, or if no ordinary occurs in the coat of arms, as in Fig. 38, then that charge should be named which occupies the fesse point, and in this case the position of the charge is never mentioned, because it is understood that it occupies the middle of the field. When there are two or more charges on the same field, but none actually placed on the fesse point, then that charge is blazoned first which is nearest the centre and then those which are more remote. All repetition of words must be avoided in depicting a coat of arms, the same word never being used twice over, either in describing the tincture or in stating a number.

Thus, in blazoning Lord Scarborough's arms (see coloured plate), we must say: "Arg., fesse gu., between three parrots vert, collared of the second," the second signifying the second colour mentioned in the blazon—viz., gules. Again, if three charges of one kind occur in the same field with three charges of another kind, as in the arms of Courtenay, Archbishop of Canterbury, who had three roundles and three mitres, to avoid repeating the word three, they are blazoned, "Three roundles with as many mitres."

When any charge is placed on an ordinary, as in Fig. 41, where three calves are charged upon the bend, if these charges are of the same colour as the field instead of repeating the name of the colour, it must be blazoned as being "of the field."

We now come to those charges known as "marks of cadency." They are also called "differences" or "distinctions."

Fig. 36.

Cadency—literally, "falling down"—means in heraldic language, "descending a scale," and is therefore a very suitable term for describing the descending degrees of a family. Thus "marks of cadency" are certain figures or devices which are employed in armorial bearings in order to mark the distinctions between the different members and branches of one and the same family. These marks are always smaller than other charges, and the herald is careful to place them where they do not interfere with the rest of the coat of arms. There are nine marks of cadency—generally only seven are quoted—so that in a family of nine sons, each son has his own special difference. The eldest son bears a label (Fig. 36, 1); the second, a crescent, (2); third, a mullet (3)—the heraldic term for the rowel of a spur3; the fourth, a martlet (4)—the heraldic swallow; the fifth, a roundle or ring (5); the sixth, a fleur-de-lys (6); the seventh, a rose (7); the eighth, a cross moline; and the ninth, a double quatrefoil. The single quatrefoil represents the heraldic primrose. There is much doubt as to why the label was chosen for the eldest son's badge, but though many writers interpret the symbolism of the other marks of cadency in various ways, most are agreed as to the meaning of the crescent, mullet, and martlet—viz., the crescent represents the double blessing which gives hope of future increase; the mullet implies that the third son must earn a position for himself by his own knightly deeds; whilst the martlet suggests that the younger son of a family must be content with a very small portion of land to rest upon. As regards the representation of the other charges, the writer once saw the following explanation in an old manuscript manual of French heraldry—namely: "The fifth son bears a ring, as he can only hope to enrich himself through marriage; the sixth, a fleur-de-lys, to represent the quiet, retired life of the student; the seventh, a rose, because he must learn to thrive and blossom amidst the thorns of hardships; the eighth, a cross, as a hint that he should take holy orders; whilst to the ninth son is assigned the double primrose, because he must needs dwell in the humble paths of life."

3: A mullet is generally represented as a star with five points, but if there are six or more, the number must be specified. It must also be stated if the mullet is pierced, so that the tincture of the field is shown through the opening.

Fig. 37.

The eldest son of a second son would charge his difference as eldest son, a label, upon his father's crescent (Fig. 37), to show that he was descended from the second son, all his brothers charging their own respective differences on their father's crescent also. Thus, each eldest son of all these sons in turn becomes head of his own particular branch.

When a coat of arms is charged with a mark of cadency, it is always mentioned last in blazoning, and is followed by the words, "for a difference." Thus Fig. 43 should be blazoned, "Or, kingfisher with his beak erected bendways4 proper with a mullet for a difference gu.," thus showing that the arms are borne by a third son.

4: The individual direction of a charge should be blazoned, as well as its position in the field.