The PEEP of Bologna was adopted on 21 June 1963. The ratification of the inclusion of the Pilastro within the PEEP as the »thirteenth area« took place in May 1964 and was introduced by Campos Venuti during the city council session on the same day:

The neighborhood of the Pilastro at issue consists of a complex of almost 10,000 inhabitants, 9,677 precisely […]. In total, an area of almost half a million square meters with a building area of less than half of the total, with a series of road provisions, school, cinema, church, parking garage, all equipment, in other words, provided by urban standards adopted for the plan in a broad sense and applied for this district in proportion to the area and population.281

The first plan for the Pilastro of 1960 conceived the neighborhood as a »self-sufficient settlement« divided into two residential complexes, among which a public park and sports facilities were collocated. According to this plan, the whole settlement was organized in two symmetrical semicircles, each of which was composed of three concentric areas. The external belt of each semicircle was characterized by blocks of low houses with an irregular and lined up profile. The intermediary belt was comprised of high residential buildings, while the inner semicircle included tower buildings with a mixed use (offices, houses). It also should have held the »community’s social functions, like the church, municipal offices, schools and other commercial and cultural services.«282 Besides, the north side of the settlement continued to an artisan zone, separated from the residential area by a thin green belt.

Architects initially conceived the Pilastro as an autonomous community with precise, although »vaguely idyllic«,283 identity connotations. Social implications of the plan were strictly connected with both geographic and productive aspects of the neighborhood:

Convinced of the need for an inter-class composition of the village, without insignias and without forced agglomeration of similar interests, a free development of forms and volumes has been devised in which men of every condition can feel at ease and in which the face of things can remain in memory, where finally, the community can gather on Sunday in the churchyard, in leisure, not having lost touch with nature, with the green, with the land.284

The inclusion of an artisan area in the Pilastro was intended to offer »a right model through which these small firms can virtuously fit into residential settlements«, trying to minimize commuting and anticipating decentralization that »out of control would have broken in towns of Bologna’s belt«285 during the sixties and the seventies. According to the intentions of the designers, the neighborhood self-sufficiency depended necessarily on its productive and employment self-sufficiency.

This first plan was devised in the light of housing 15,000 inhabitants, while the cubature of the buildings was estimated at 1,210,000 cubic meters for a density of 2,40 cubic meters/square meters. Nevertheless, it was rejected by the City Planning Department, which asked IACP to draw up an alternative solution. In 1963, the IACP and the Municipality established an agreement on their respective tasks: the agency should build inner roads and buildings, while the Municipality should provide the settlement with main roads, public lighting and services.286 In the same year, the definitive plan for the Pilastro was elaborated: the artisan area was substituted by simple shops; the area to be occupied by the buildings was reduced; and only one typology of building (8-story blocks in a line) composed the two semicircles for a total population reduced to 10,000 inhabitants.

The reduction of both the expected population and the building area resulted in an increased building density. In addition, the exclusive residential use of the buildings and the gradual abolition of the artisan area determined the mono-functionality of the Pilastro, which turned into a bedroom suburb on the edge of the city.287

On 9 July 1966 the first 411 apartments of the Villaggio del Pilastro were eventually inaugurated. On that occasion, the new IACP president, Elio Mattioni, affirmed:

The new neighborhood was designed to be both the most convenient from the economic point of view and the most efficient from the urban point of view. […] When all the planned buildings are completed, the village will be divided into contiguous units that constitute centers of authentic social measure, each with its essential services. All the harmony and expressiveness of the new neighborhood are conferred to the reasoned game of volumes and the shrill tones of the plasters. Deep in the green, the village—which nicely integrates with the surrounding countryside—guarantees, with its open spaces and its bright prospects, a comfortable environment for its new inhabitants.288

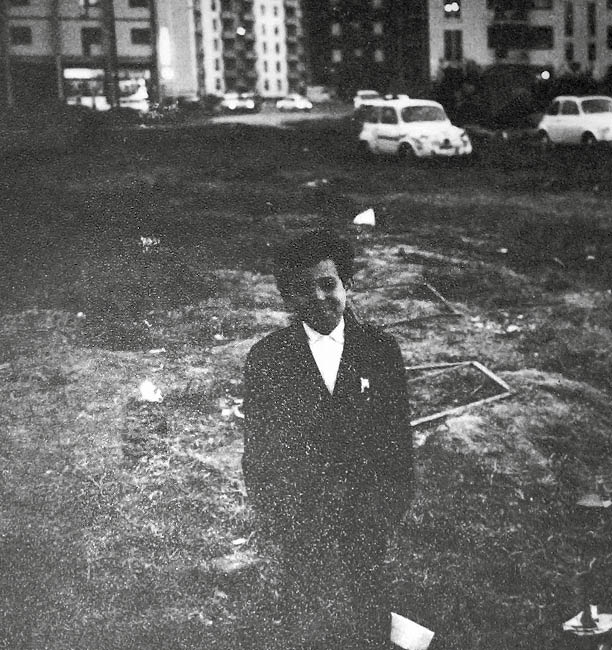

Fig. 1: Inauguration of the »Villaggio del Pilastro«. 9 July 1966. Authorities stage.

Source: Archive of the photographic exhibition, I vent’anni del Pilastro, mostra antologica retrospettiva, grafici, foto, documenti, 1–18 ottobre 1987, Palazzo Re Enzo, Sala del trecento, Bologna.

The enthusiastic expectations by Mattioni would eventually remain unrealized when looking at a report of December 1970 that describes the actual scenario the first dwellers faced once having arrived in the suburb:

The village of the Pilastro, built years ago, immediately presented major conceptual flaws. Terrible buildings near a continuous source of noise (railway yard), absolute lack of walkable green spaces, lack of primary and secondary schools, kindergarten, nursery, [namely] all social services as essential as the house. Lack of spaces for recreational, cultural, sports and political associations, [for] a community center [and] the parish. High-cost domestic services (heating, elevators, gas, water), or at least not affordable for the family budget of most citizens. Conversely a social stratigraphy, mostly made up of large working-class families. In short, a large urban agglomeration that from day to day is gaining the typical features of suburban districts such as those of Milan, Turin, Rome, Naples, Palermo etc.

Houses designed in a purely speculative way, buildings without terraces, stinking sewers, gutters that, after three years, rot and rain water flowing down the walls. Shops with luxury prices, areas of land left to themselves with various waste piles, narrow and twisted roads, lack of garages promised but not built at the time and very expensive ordinary maintenance paid directly by the tenants—intercoms planned in the project and unrealized.289

In fact, as soon as July 1966, the first inhabitants had »experienced a reality […] mainly characterized by difficulties in housing. First, the lack of health care facilities, schools [and] adequate transport services.«290 Being faced with this situation, a group of tenants decided to form the Comitato Inquilini del Pilastro with the aim of »establish[ing] relations with both the IACP and the Municipality, in order to convey and examine the many structural, organizational and administrative problems that bother all of us inhabitants of the Village.«291

As claimed by Mario Zaghi—the secretary of the Comitato in the late seventies—the decision to form a tenants union stemmed from the simple observation that »discussing and uniting«292 together the various problems would be solved more easily and therefore—as stated by another of Comitato’s member, Angiolino Vecchi—»it would be totally useless to go individually to the Institute [IACP] or to the Municipality to reclaim this or that right.«293

In essence, since its establishment, the Comitato sought to act as the collector of the residents’ requests and claims toward the IACP and the Municipality. To achieve this, the Comitato resorted to a dual strategy from the beginning. On the one hand, its demands followed a strictly institutional path. Thus, through dialogue, consultation, meetings, exchange of correspondence, the Comitato tried to influence the decision-making processes that dealt with various aspects of the village such as rent prices, urban planning and the provision of public services.

On the other hand, especially when its demands were not met or when the red tape or lack of coordination between agencies made some problems particularly urgent—as in the case of the delayed construction of schools—the Comitato resorted to forms of mobilization such as strikes or demonstrations in central Bologna to raise awareness amongst institutions and the public.294

On 26 June 1967, the Comitato Inquilini had formalized its composition. The president was Luigi Spina and the secretary was Oscar De Pauli. For »a better functionality« three ad hoc committees were created. They were respectively dedicated to the relationships with the IACP, those with the Municipality, and the school situation.295

According to its statute, the Comitato Inquilini was »a financially and administratively independent association« aimed at »safeguarding, coordinating and protecting the economical, social and moral collective interests of the inhabitants of the neighborhood.« Its duties were to »regularly inform […] tenants on crucial initiatives affecting the tenants themselves« and »to maintain a non-partisan line« with the aim to avoid that its action »could be characterized as an appendage of any political party.«296

However, the question of the political affiliation of the Comitato was not so linear. Despite claiming to be apolitical, including »citizens with or without any political ideology« motivated »by a spirit of class or Christian solidarity […] or even simply by altruism«,297 the Comitato somewhat strengthened the relationships with the PCI thanks to the foundation of the PCI section »V. Sabatini« at the Pilastro in 1969. From the report of the PCI Comitato di quartiere of the adjacent neighborhood, San Donato, a growing crisis of representation of the organizational apparatus of the PCI at the neighborhood level clearly emerges, in a phase when grassroots positions within the party and especially the action of groups of the extra-parliamentary Left showed itself to be more able to interpret bottom-up protest. The solution to avoid a possible loss of hegemony in the neighborhoods was to empower local sections and, above all, to join those segments of »civil society« that were already operating on the territory. In this sense, the newly formed section of the PCI at the Pilastro was noted as the only center of political initiative in the San Donato district. The »communists« of the Pilastro were particularly active »not only in a section of the PCI, but also in the Comitato Inquilini, in the movement school and society, in the committees for self-management of the school.«298

The link between the PCI and the tenants union is also demonstrated by a PCI meeting held in April 1969 at the bar Dall’Olio—a usual venue for meetings of the Comitato at that time—where the new secretary of the section »Sabatini«, Aldo Grenzi, was elected. The goal of the PCI was to »be present with more incisiveness at the Pilastro«, with the aim of »reducing the space« of political action for a group of students belonging to the Unione Comunisti d’Italia Marxisti-Leninisti that »had chosen the area of the Pilastro to create a popular base« among its inhabitants. To do this, it was essential, according to the PCI, that »the PCI section secretary [was] not also the Secretary of the Comitato Inquilini.«299 Beyond testifying to the Comitato’s nonpartisanism in the eyes of tenants and, above all, far-left groups, the distinction between the charges of the Comitato and the local PCI would allow the latter to have a local secretary who could deal with the party within the neighborhood full-time. Thus, a continuity between the PCI and the Comitato Inquilini at the Pilastro clearly emerges.

Morever, between 1970 and 1971, the Comitato promoted a campaign to collect signatures for a popular law aimed at reducing rents by 30 percent and initiating the democratization process of the IACPs through the entry of representatives of the tenants into the institutes’ decision-making process. This petition—»launched at the national level from Milan«300—was signed by 1,300 tenants and had a clear left-wing tendency related to union struggles triggered by the Autunno caldo of 1969.

In the same period, however, tenants engaged in other forms of protest against high rents: there were »dozens« of families »that, for months, no longer pay rents to the IACP.«301 Groups from the extra-parliamentary Left, such as Lotta Continua and the Maoists of Servire il popolo, attempted to exploit such forms of needs-driven protest but with poor results since they were never able to take root in the neighborhood. According to the newspaper Il Resto del Carlino, the activists of Servire il popolo »[were] convinced to find those underclass conditions capable of sowing the seeds for an Italian-style Maoist revolution, but they found workers involved in a really concrete, and not utopian, terrain of democratic struggle«; and also for Lotta Continua the »Pilastro has become a trap that has defeated and rejected them, isolating them even more by the masses.«302

Angiolino Vecchi highlighted the different strategy opposing the tenants union and Lotta Continua in this protest against high rents:

Several tenants already turned to us of the Comitato and asked: »Is it true that we do not pay rent?« […] Who invites us not to pay the rent and »to make the rent strike« is not the Comitato Inquilini, but a group from Lotta Continua. [They] are a political movement calling itself »Marxist-Leninist«, but they are not the »communists« as intended by the majority of Italians. They are so-called »Maoists« or »Chinese.« And what do they want? […] Actually, maybe they do not even know it: they just say to want »the revolution«, yes! But since it is a bit difficult today in Italy [to] build barricades, here this small group of »revolutionaries«—who do not even live here at the Pilastro (do not forget it!)—have seen fit to choose our neighborhood, ruling that its population is the most suitable in the city for their own purposes, perhaps because—so they believe—composed of fools and ignorant, so ready to accept their miraculous programs. In fact, it is very easy to say: »you do not pay the rent.« It is quite an appealing program, is not it? But have you tried to ask these types if they pay their rent? I asked them, and you know what I was told? »Yes, I pay the rent because I do not live here and I have another landlord.« Got it now?

[…] We think that the battle for the rents should be conducted, as we are doing now, in the political and trade union field, and that the fighting systems proposed by Lotta Continua are out of touch. Years ago we decided not to pay rents, and many of you will remember it. But you also will remember that it was for a specific purpose: we wanted the IACP to listen to our reasons relating to heating, with the aim of lowering the bills it charged us. And the Institute… lowered costs.303

This marked distance, or opposition, between the Comitato and the groups of the extra-parliamentary Left can be explained in generational, social, and political terms. In fact, Comitato members were all workers living at the Pilastro and having an average age definitely higher than that of the members of Lotta Continua. Also different were their goals, their methods and their responsibilities: while the Comitato set out to solve the problems of the neighborhood by legal methods and on the basis of a purely tenant union demand platform, the »revolutionary« groups had a strong ideological approach and unrealistically aspired to »raise the level of confrontation« within an allegedly »underclass« neighborhood. But above all, from the Comitato’s standpoint, only those who lived at the Pilastro could fully act for the benefit of its inhabitants: those who did not experience the reality of the village just played at being revolutionaries in an exotic terrain, by assuming a naïvely »pedagogic« attitude.

Harsh criticism, however, also followed the opposite direction. In a leaflet of January 1969 the Gruppo per la formazione del comitato di lotta del Pilastro, the first far-left group that tried to take root in the neighborhood, described the Comitato as the »faithful servant« of the IACP: according to this group, the committee pretended to »advance the interests of workers« but in fact »it was made up of employees and policemen whose sole task was that of keeping the tenants-workers under control in the interests of the Institute.«304

Instead, the contrasts between the PCI and Lotta Continua at the Pilastro became apparent in July 1971. On 3 July, eleven families occupied some newly built apartments owned by the IACP. »Within a few days the families became 42«,305 occupying an entire building in via Frati. These were »workers, laborers, truck drivers,« who mainly came from southern Italy and already lived in dilapidated houses in other outlying areas of Bologna, such as Borre, Noce and Beverara outside Porta Lame.306 The families were led by Lotta Continua activists, but the distribution of apartments among the occupants, the line to follow in dealing with the IACP and, in general, all stages of the protest were managed by an assembly of heads of household. The occupation lasted one week, during which the assembly of heads of household tried unsuccessfully to achieve a compromise with the IACP. The PCI sought a dialogue with the occupiers, but despite some communist grassroots members supporting the reasons for the protest, the official line of the party condemned the occupation. According to the PCI Comitato cittadino, occupations generated a dangerous conflict between occupants and recipients, while Lotta Continua demonstrated irresponsible exploitation »of desperate situations for actions for their own sake.«307 The Comitato Inquilini responded along the same lines while not releasing an official statement on the matter.308

For its part, the IACP claimed that, contrary to what the Resto del Carlino stated, the occupied apartments were not intended for rental-purchase, but were already allocated for rent to »workers, the disabled and the elderly currently residing in unsanitary or totally inadequate housing, or subject to eviction.«309 Lotta Continua, however, extolled the organizational capacity of the occupants with emphatic tones, pointing its finger at the PCI, the Municipality and the IACP at the same time. It saw them as responsible for »isolating the struggle« and leaving the field open to the »repression« by that police that evicted the occupied apartments on 10 July. Lotta Continua stressed the fact that »for the first time in Bologna the PCI had remained on the defensive« and that even in that city that was »propagandized throughout Italy as a ›city on a human scale‹ […] ghettos and social degradation« existed.310 The activity of Lotta Continua at the Pilastro ended with this, all in all, unsuccessful experience.

However, although the methods of the Comitato were certainly more moderate than those of far-left groups, its relations with the IACP were not always idyllic. As seen above, in December 1970, the president of the tenants union, Luigi Spina, defined IACP’s apartments as built »in a purely speculative way«, highlighting their poor quality. He also associated the Pilastro to the reality of other Italian cities where much more large-scale migration, or less attention of local governments toward public housing, had resulted in slums or a structural shortage of affordable housing for the working classes.

In fact, the Pilastro could be seen as an anomaly compared to other districts of the so-called Third Bologna since it lacked the high standards of equipped green, public services and shopping centers characterizing this new city belt, which basically coincided with the PEEP areas built up during the sixties. One of the reasons for this lay in the fact that the Pilastro was designed as an INA-Casa village of the fifties311 at a time when that social-housing scheme was replaced by the »PEEP paradigm«. In addition, municipal technicians progressively distorted the original idea of the village as a self-sufficient neighborhood as regards work and production. According to other interpretations, the marginality of the rural areas acquired by the IACP in 1959—located outside the urbanized fabric—represented the »original sin« that heavily influenced the Pilastro’s future developments.

Besides, while the first buildings of the Pilastro, in the sixties, were funded under laws 17 and 1460 of 1963,312 the PEEP variance of 1968 was instead launched to coincide with the legge Ponte of 1967,313 while finally the PEEP variance of 1975 was designed to harness public financing offered by laws 865 of 1971 and 166 of 1975.314 These continual regulatory and funding changes entailed a differentiated rents policy by the IACP even within the same village. In particular, if the rent of the first apartments delivered in 1966 amounted to 11,300 lire per month for houses consisting of two rooms and a kitchenette, and 23,032 lire per month for five-room apartments, the rent for those built in 1970 rose to 19,690 lire per month for homes with three rooms and a kitchen and 29,500 lire per month for apartments of five rooms and a kitchen.315

The gap is huge if compared to other areas of the »public city«: in the Barca estate, for instance, the rents ranged from 5,500 lire a month for a flat with five rooms to 6,650 lire for a house with six rooms still in 1970. At the Pilastro, rent prices were even higher than those charged by private landlords in the adjacent San Donato district.316 Unlike Barca, where housing had been built thanks to state contributions of GESCAL (i. e. the continuation of the INA-Casa program), at the Pilastro the laws financing the construction of housing only granted the IACP a small state contribution oscillating between two and four percent of the total expenses. In the virtual absence of state financings, the IACP was then forced to take out loans with the Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (a state financial bank) and, thus, to fix above-average rents to repay its debts.

This kept rent strikes continuing also in March 1972. The lack of state resources covering law 865 of 1971—which was meant to finance social housing—did not allow the IACP to accept the Comitato’s proposal of reducing monthly rents by 30 percent, thus inducing the latter to organize a full rent strike, although only limited to that month. However, some dwellers fought high rents in more drastic ways if the Comitato invited the newly arrived tenants not to confuse its own initiative with that of the »group that proposes the systematic selfreduction of half of the rental fee each month«.317 Nevertheless, despite high rents, at the Pilastro the percentage of delinquent tenants was in line with that of other IACP-managed social housing estates.318