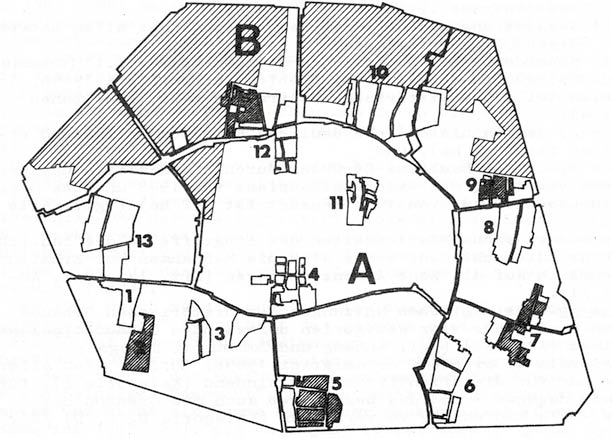

Fig. 1: The historical city center of Bologna today.

Source: Harald Bodenschatz, 2010.

Forty years ago, Bologna was a unique urban place of pilgrimage.555 Monumental conservators, architects, city planners, social scientists, politicians and the politicized from all over the world made their pilgrimage into the regional capital of the Emilia Romagna. In various ways, the Bologna model marked a turn in urban development policy. Five main dimensions of it found recognition beyond professional circles: firstly, the preservational urban renewal of the entire historic city center; secondly, the concept of the city as a network of public services; thirdly, the social perspective of residential modernization; fourthly, the project of municipal decentralization; and, fifthly, the perspective of a social policy of regional planning which became possible by the institutionalization of the regions. Together, these five dimensions constituted the urban development program, which was summarized by contemporaries with the term the »Bologna model«.556

Fig. 1: The historical city center of Bologna today.

Source: Harald Bodenschatz, 2010.

The Bologna model was neither coincidence nor merely a local phenomenon. It was an expression of a social transformation, an expression of a range of social movements in Europe which were dealing with the built and political situations in cities. These movements went well beyond what is often known as a »student movement«. They transformed established parties and institutions. This radical change, which lasted many years, culminated in the European Architectural Heritage Year of 1975, which was characterized by the interconnection of initiatives from above and below. Bologna was the most important flagship of the European Architectural Heritage Year557—it symbolically concentrated actions all across Europe in a »cult« location. In Bologna, it was the »Eurocommunist« party that first offered a platform for new ideas and people, some of which came from universities. In »red« Bologna, limits to these changes soon became visible. They were founded in local social structures and the strong economic middle class, which basically constituted the basis of the Eurocommunist party and opposed radical reforms.

My connection to this topic area is multiple: I am a biased contemporary, eye-witness and activist as well as a scholarly observer. This is a difficult mix, as is well known. I lived in Bologna in 1975–1976, during the years of euphoric enthusiasm about the Bologna model and completed my doctoral studies there on the topic.558 I was then in Bologna with another scholarship recipient, my friend and colleague Tilman Harlander, who would later become professor at the University of Stuttgart. Harlander completed his doctoral studies with a focus on the regional policy of the Emilia Romagna.559 Later, Lothar Jax followed with a dissertation about district democracy in Bologna.560 All three of our doctoral degrees were completed at the Department of Planning Theory of the RWTH Aachen.561 In addition, I later often analyzed the history of European urban renewal.562

In this chapter I will first explain the five dimensions which characterize the Bologna model. After briefly pointing out the moments of crisis of this model in the second half of the seventies, I will propose a few reflections as to the contrasts between the »Bologna model« and current neoliberal policies.

Until today, Bologna has been known for its policy of preservational renewal of the historic center. The most spectacular dimension of the Bologna model lies in a cultural reassessment of the historic center. No longer should just select famous buildings be protected, but rather the whole center as a heritage ensemble. For decades across Europe, simple historical buildings and the urban structure of historic cities had been considered unacceptable, without further value and therefore not worthy of protection. Meanwhile, in Bologna, the entire urban heritage, even simple craftsman’s buildings, was awarded the status »worthy of protection«.

The historic building stock of Bologna’s city center was, alongside Venice’s, the most extensive in all of Italy. The structure of the historic center with the Via Emilia and regular street network dates back to the Roman period. In the Middle Ages, the urban center had expanded significantly and remained largely unchanged until the political unification of Italy in 1861. The pre-industrial structure of the center, especially in the north, was only changed by the construction of the train station, the urban renewal measures of the period of Italian fascism and the bombs of the Second World War. Il piano regolatore generale, the master plan, approved in 1958, protected only the principal monuments in the city center. Beyond that, it planned for massive breakthroughs for traffic and expansions. A change of course was prepared already in the first half of the sixties.563

Fig. 2: Plan of the historical center of Bologna: Zone A and B as well as 13 renewal areas, 1969.Source: Harald Bodenschatz, Städtische Bodenreform. Die Auseinandersetzung um das Bodenrecht und die Bologneser Kommunalplanung (Frankfurt, New York: Campus Verlag 1979), 176.

In the end, it was the planning foundation for the built preservation of the historical center, the Piano per il centro storico—the »Plan for the Historic Center«—from the year 1969564 which put an end to a lengthy debate about a new urban development policy for the center. The plan viewed the historic center within the fourteenth century city walls as »one monument«.565 This area corresponded to Zone A, the central zone, while Zone B referred to those areas which had been significantly transformed during the previous century. Zone A covered an area of 336 hectares. Within this zone, 13 redevelopment areas were defined in which the building stock was to be actively renewed. In regard to the use, the center was to be maintained as a residential area. Functions such as the university, culture, tourism and representative institutions, specialized business and retail were considered compatible with the urban structure. Highly frequented public administration departments, department stores and depots were considered incompatible. Public and private offices with more than ten employees were excluded from the zone. Even individual motorized transport was to be limited.

From the very beginning, the Bologna model did not just apply to the historic building stock, but was imbedded in an overarching urban development program, which culminated in a concept of public services. According to the prevailing point of view at the time it was the city’s task to offer public services which would serve basic needs. This included schools, healthcare facilities, green spaces, streets, etc. Public consumption was to have priority over private consumption—following in the tradition of the criticism of the »Abundant City«, which was current at the time. The city, which was to be structured by public institutions, became the new urban model of the master plan of 1970.566 This plan became the »plan of public services«. It promised more services and a better, more even distribution of the services between the center and the periphery. The master plan proclaimed the »right to public services«, even the »right to city«567. This programmatic orientation was expressed mainly in the drastic reduction of building spaces and the development of urban standards which defined the desired space for public services per capita. The plan also defined the spaces necessary for public services. The »Hill Plan« of 1969568 which prohibited the development of urban sprawl in the hill zones located just south of the center is also of great importance in this context.

Fig. 3: An example for the program of public services: existing (black star) and planned (black star in circle) elementary school, Masterplan of 1970.

Source: Piano Regolatore Generale, adottato dal consiglio comunale il 6 aprile 1970 (Bologna: 1974), after 150, figure 18.

The designations made in the plan oriented themselves along a four-year investment program for exceptional measures and was presented in 1972. Particularly, the number of nurseries and kindergartens, experimental all-day schools and afternoon schools was increased significantly. The attractiveness of public transport was successfully improved. Since April 1973, free travel for select groups was introduced and, during the rush hour, for all passengers. Car traffic within the historic center decreased by 20 percent. In the health sector, 14 outpatient clinics were established. The public green space was nearly doubled. Huge green spaces were purchased by the city in the hill zone and opened up to the public.569

The concept of housing as a public service570 was the most radical aspect of the Bologna model. It was the crowning feature of the general concept of public services. Those responsible knew that even a preservational renewal of the historic building stock could potentially lead to »marginalization, segregation and regrouping of the population«. For this reason it was necessary, according to the conceptual protagonists of the Bolognese model—Pier Luigi Cervellati, Roberto Scannavini and Carlo De Angelis—to connect »measures regarding the historic building ›shell‹ with equally detailed measures regarding the social ›content‹.«571 With this, a further dimension of the Bologna model was addressed. The social orientation of the urban renewal policy was an attempt to prevent the displacement of the poor population.

Against this background, in October of 1972, a draft plan for social housing in the historic center was presented—the Piano delle aree per l’edilizia economica e popolare or PEEP/centro storico.572 In this case, social housing did not—with only few exceptions—amount to new housing construction. With this draft plan the Bologna model reached its political climax. The plans for social housing construction of the sixties were subjected to a sharp critique. This did not refer to the buildings themselves, but rather to the social dimension. The »working class aristocracy« was named as the main beneficiaries of the plan. Contrary to the sixties, the center was now considered to be the junction of social conflicts. It was to be the stage for a discussion about the housing question. In the center, the displacement of poorer residents was to be prevented and cheaper housing units were to be maintained.

Fig. 4: »Against ›luxory ghettos‹ in Old Towns«. Headline in the daily paper »Aachener Nachrichten« from 31.10.1974. The by no means outdated slogan referred to a conference on »Old Towns« of the Council of Europe, which took place in Bologna, October 1974. In the last paragraph it says: »Numbers and facts from Bologna impressed the participants of the conference of the Council of Europe to such a degree, that they unanimously recommended this model to be emulated.«

Source: Private collection Harald Bodenschatz.

The draft plan for constructing social housing in the historic center affected the 13 selected urban renewal areas, which amounted to a total of 6,500 housing units. On some of the properties, which were not developed after the war, the typological reconstruction of original buildings as »renewal hotels« for temporarily housing the tenants of houses under restoration was planned. This was also intended as a means for preventing even a temporary displacement of the residents of the quarter during the renewal process. The term typological reconstruction refers to the reconstruction of destroyed buildings in their historical forms, a practice that was considered to be a logical part of urban heritage protection.

As a suitable means for realizing the concept of »housing as public service«, the draft plan determined the so-called housing cooperatives with undivided property (cooperazione di abitazione a proprietà indivisa). In this form of cooperative residents would not become the individual owners of their flats after the dispossession of the original private owners, but rather collective owners of cooperative property—a form of »undivided property«. This also means that the tenants did not have to make advance payments, but rather had to pay a fixed, political rent. Furthermore, they would gain a lifelong right of residence, but would be able to change flats within the urban renewal area. There was no more room for private residential modernization projects within this concept.

In order to apply planning instruments of social housing construction for the dispossession of buildings a special interpretation of the national law on social housing, the so-called legge sulla casa (Legge 22 ottobre 1971, Number 865),573 was required, as the law did not clearly mention the possibility of dispossession in urban renewal areas. The planning institutions of Bologna mastered this hurdle. They declared the dispossession of the buildings, designated for modernization, as a »public service«, as the legge sulla casa allowed for dispossession in the context of public services.

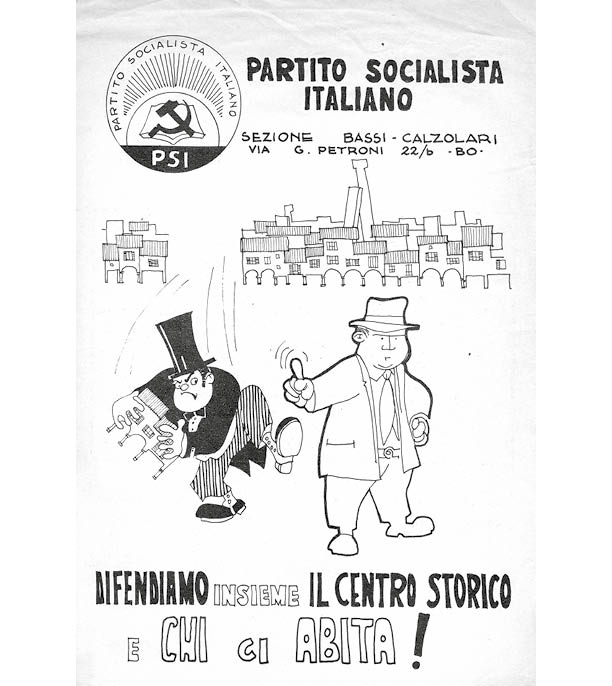

Fig. 5: Leaflet of the Socialist Party of Italy (PSI) in support of the urban renewal policy of Bologna, 1975: »Let us defend the historical center and its residents!«Source: Private collection Harald Bodenschatz.

The draft plan of 1972 became—entirely unexpected for Bolognese planners—the starting point of the most heated debate since the beginning of the reform process. The media campaign against the draft plan reached its highest point by the end of the year. The Bolognese newspaper Il Resto del Carlino declared the draft as »insidious«, »Marxist« and »collectivist«.574 The dispossession of private property owners became the central social point of contention. The local communist party and the planners went on the defensive. The dispossession concept was withdrawn, step-by-step, and finally abandoned altogether. An entirely new concept emerged at the end of the conflict: the new form of acceptable urban renewal amounted to modernization projects through private house and property owners on the basis of contracts between the property owners and the city. In these contracts, a maximum rent limit and a communal occupation right were to be determined.

The new version of the draft plan for social housing in the historic center was passed by the local council in March 1973. The duration of legal binding was still undecided and controversial. This was not determined until March 1975, but amounted to 15 or maximally 25 years. Even the communal occupation right was suspended. With this the cooperative project of undivided property and the associated form of self-government failed. However, a social orientation remained within the context of urban renewal policy, even if it was significantly limited.

In view of these conflicts and delays, the results of the plan for social housing construction in the historic center were modest. Only 58 housing units could be completed by the end of 1976.575 Through the dilution of the social orientation of housing policy, a development began in Bologna which is known today as gentrification. In the context of the renunciation of property dispossession, the expansion of public services led to a rise in property prices and a slow displacement of long-time residents.576

Since 1964 district councils have existed in Bologna. These councils first had only a consultation competency and their work was limited to completing administrative tasks.577 This traditional form of decentralization was called into question by the end of the sixties. As a result, a larger grassroots movement emerged in the field of urban development which influenced municipal planning policy through newly instituted urbanism commissions on a district level.578 The master plan of 1970 passed the expansion as well as the management of public services on to the district-level institutions.579 Thereby, these institutions were awarded a political, rather than just an administrative consulting role. In fact, these institutions were largely involved with the formulation and implementation of the Bologna model in the first half of the seventies.

In March 1974, the Bologna city council decided in favour of a change of the statute which determined the responsibilities of district institutions in Bologna. The first alderman of the mayor now became »district president«; the members of the district council were to be elected indirectly—decided by the parties according to the share of the votes in municipal elections; and existing, new institutions such as the urbanism commissions and public assemblies were officially recognized. The city was now required to obtain suggestions from the district institutions with regard to all major decisions. The district councils received the right to develop a district budget plan and implement urban development measures, as long as these affected the district. Politically, in this context the concept of so-called »social control« was fixed. Municipal decentralization was now far more than just a consulting activity or district control from above.

The issue of municipal decentralization gained a specifically structural character in Bologna as large historic monastery complexes were selected to become the seats of district democracy. The first community center (centro civico) was opened in the Lame district in 1974 and three more community centers were established in the historic center in 1975 and 1976. The community centers served not only as the seat of the district democracy, but also offered room for public services such as outpatient clinics, libraries and recreation facilities. Therewith, an abstract organizational form acquired a spectacular spatial expression. The enormous monastery complexes gained a new form of use.580

Municipal decentralization was just one part of the restructuring of the state apparatus in the first half of the seventies. A process of state decentralization, which ended with the transfer of state administration tasks to regional jurisdiction in 1972, was initiated with the election law of 1968, the financing law of 1970 and the opening of the possibility to adopt statutes. In this process Bologna became the political and administrative seat of the Emilia Romagna region.581

As a result of a broad debate, a statute for the newly planned Emilia Romagna region—a type of mini-constitution—was passed with cross-party consensus in December 1970.582 From an urban development perspective, the statute, which was strongly influenced by the PCI, required a social orientation. This included especially the comprehensive supply of public services to the population, a balanced spatial development and effective citizen participation. In March 1973, the draft of a regional development program was presented and sparked a broad discussion. The goal of the draft was the »public control over the development of the territory« in the sense of an overcoming of existing imbalances. Explicitly, targets such as comprehensive landscape protection, protection of historic centers and the expansion of social housing were called for. These demands were bundled in the solution of »housing and city as public service«.583 The regional budget plan of 1974 defined clear priorities in the urban development sector in favor of public transport, social housing construction and landscape protection.

Around the mid-seventies, the Bologna model had finally emerged: a program and practice that set new structural, social and political benchmarks of European importance. Structurally, it oriented itself along urban renewal instead of urban expansion. This meant that in practice, the preservational urban renewal of the historic center which was in its entirety, not just individual buildings, was understood as an urban monument. The concept of the city was socially developed as a network of public services, which was to be expanded and distributed fairly. Even housing was no longer considered as a marketable commodity, but rather as a public service. The new housing policy was no longer meant to serve the working-class aristocracy, but rather the poorest and, therefore, also southern Italian immigrants. The Bologna model was flanked by a reform of the public institutions, which affected two spatial levels: the district and the regional level. The model was financed through deficit spending, a Keynesian financial policy, which had been practised in Bologna since the sixties.584

Fig. 6: Student leaflet against austerity policy in Bologna, 1977.

Source: Private collection Harald Bodenschatz.

Around the mid-seventies, the Bologna model experienced a major crisis. This crisis was based, at first glance, on the difficult economic situation which called the implementation of the ambitious social services program into question. However, the ways and means in which the communist party had been reacting to this crisis since 1976 was a deciding factor. The communist party forced the implementation of an austerity policy on the local level, which contrasted sharply with the deficit spending policy practised in the first half of the seventies. The limitation of public spending became the central goal of Bologna’s municipal policy.

This change of course in budget policy resulted in the adjustment of tariffs for public services. Price increases for gas, water, for school meals, day-care facilities and public transport followed in 1976 and 1977, respectively. At the same time, the services themselves were reduced. For example, opening hours for kindergartens were decreased and the frequency of public transport reduced. Even the rent for public flats was increased. The character of district democracy also changed as a result of the austerity policy. The planning, administration and expansion of public services were not main issues any longer. Rather, the focus was set on the implementation of austerity measures on a district level. All of these measures fundamentally undermined the Bologna model. It constituted the background for new conflict fronts and social conflicts which intensified after March 11, 1977, the death of Francesco Lorusso, a student and member of Lotta Continua.585

Until the mid-seventies, the fascination with the Bologna model was based on its dual orientation: first, as the design/image-based, preservational and building-based policy; and second, as a socially-oriented policy with regard to the use of buildings and urban space communicated through new forms of participatory culture. But even this dual policy could only unfold its suggestive force through the subject itself, the historic center of Bologna, one of the largest and most beautiful city centers in Europe. The artistic and cultural dimension of the Bologna model fascinated monumental conservators and architects in particular, while social scientists and politicians were more concerned with the socio-political dimension. The general political framework was of great importance—the existence of a strong Eurocommunist city government, as expressed in the formula »the red Bologna«. This aspect mobilized the highly politicized professional sphere from other European countries to a great extent, not only in the sense of burning admiration, but also in a critical sense. The Eurocommunist perspective was controversial in a scientific community which considered itself to be progressive.

Today, or rather, since the eighties, the Bologna model has been largely forgotten.586 Who even knows about the complex dimensions of the Bologna model or its protagonists, such as Pier Luigi Cervellati, a former research assistant to Leonardo Benevolo? If the Bologna model is at all taken into consideration, then it is from a rather narrow architectural perspective and with a focus on the preservational urban renewal of the historic center. In fact, this dimension has turned out to be the only lasting aspect, while all others have lost their programmatic power.

In conclusion, I would like to make three final remarks about the Bologna model.

Firstly, the Bologna model was unique in regard to the specific composition of its five dimensions, not however in regard to the individual dimensions. The concept of public services had already played a significant role in the municipal policy and economy of the interwar period.587 This also applies to housing policy, even if social housing construction really only benefited poor residents in Red Vienna. Italy had some catching up to do in regard to the regional policy of territorial compensation. The municipal decentralization program was anything other than a Eurocommunist invention. Even the designation of the entire historic center as a monument ensemble was not a new idea. For example, the complete historic center of Óbidos, north of Lisbon, had been classified as a monument already in 1951 during the Salazar dictatorship. However, the combination of all of these dimensions was evaluated in a new way. Only this can explain the interdisciplinary fascination with the Bologna model.

Second of all, today’s view of the Bologna model reveals a scientific dilemma or, rather, a dilemma of my own profession, the planning discipline. We have no critical culture of evaluating »cult projects«, which is how I see the Bologna model from today’s perspective. Our profession keeps becoming passionate about one model or another, such as the cautious urban renewal of West Berlin or the renewal of public space in Barcelona. However, as soon as these models succumb to a crisis, not only the passion, but also the general interest subsides. We have no knowledge about the crises and the reasons behind them. We offer no a posteriori interpretation of these special processes. This is actually unbelievable, especially in view of the practical orientation of the planning discipline. There are reasons for this as well, such as the lack of interest on the part of affected state institutions.

Thirdly, if the Bologna model seems diluted from today’s perspective, it nevertheless marks a historical point where a fundamental change in scientific understanding took place. Today, a merely analytical perspective is preferred. During the seventies, a practice-oriented discussion was more common: on the part of planners as a model which could be imported to one’s own city, on the part of politicians as a model which could lead to a better city. The fact that this perspective not only allowed for uncritical receptions was due to the thoroughly critical debate about Eurocommunism. At the time, a practice-oriented perspective always included the debate about the political program and its implementation.588 This includes, for example, the debate about a city of public services, an issue which seems outdated in the context of the prevailing neoliberal municipal policy. Today’s perspective allows for the disappearance of this central dimension of the Bologna model. Today such a model might appear as unrealistic. Due to the complete departure from a policy of »deficit spending«, the municipalities lost all means for an expansion of their services. But looking back on the Bologna of the seventies also allows another conclusion: turning away from a policy of public services and the loss of power linked to this are no longer something like a »law of nature« but rather a result and expression of political decisions taken by actors who have deposited the »right for public services« on the trash heap of history.