Protection of Cultural Heritage and Urban Development. Catania and Syracuse in the

Seventies: A Comparative Approach

Melania Nucifora

The cities investigated here are situated in the eastern part of Sicily, an area that

changed considerably in the seventies in various ways, especially concerning the economy.

The recession that affected the local economy over that decade put an end to a period

of unprecedented prosperity. The signs of change, which were already starting to appear

towards the end of the sixties and took shape in the years that followed, also touched

the issue of protection of cultural heritage and historic urban landscape. Important

innovations involved the objects, actors and strategies of protection, the culture

of conservation itself and, finally, the nature and dynamics of the conflicts around

the historical heritage of the cities in question.

In order to understand the nature and limits of change, we should first briefly trace

the terms of the conflicts around the landscape and cultural heritage that accompanied

the age of prosperity in Italy, as well as the political and academic debate around

the issue in the three decades before the turning point.

The Great Transformation Changed the Traits of the Bel Paese

The great transformation of the postwar period was brought to a close during the first

half of the seventies; in Italy this transformation had epochal proportions that amounted

to a transition, late in coming but swift and striking, from a society deeply rooted

in centuries-old practices, cultures and traditional values to a modern affluent society.

This in large part involved the dissolution of a rural world, which took place through

a tumultuous movement of collective migration towards urban centers that saw many

Italian cities swell with new inhabitants from the provinces and the country.

The impact of the great transformation on the cultural heritage and Italian historical

landscape was so strong that it left an indelible mark on the collective memory. The

new citizens of rural origin who invaded the urban centers, first of all, had basic

needs (housing, water and roads), little or no previous shared urban identity, aspired

to different types of consumption, and their main concern was modernization and economic

growth, barely disguising the desire to put behind them a past that for many evoked

poverty and exclusion. The country witnessed mass abandonment of mountain and hilly

areas and inland villages that made up the physiognomy of the landscape that was typically

Italian and largely homogeneous, at least along the Apennine Ridge. In this way, there

was a consolidation of that demographic and economic imbalance between inland and

coast that had more distant origins, and that Rossi Doria fixed with the vivid image

of the »flesh« (the coastal, urbanized areas where industries and services were concentrated)

and the »bone« (the poverty-stricken inland country areas and mountain villages whose

inhabitants left for the urban areas and were thus reduced to the bone).682

The burgeoning housing demand subjected the historical areas of large and medium-sized

cities to unprecedented building pressure. The system of peri-urban agricultural land

was changing rapidly and established urban areas underwent land revaluation and swift,

unscrupulous demolition and replacement. The cities underwent a transformation that

happened too rapidly, within the cities and in the surrounding areas, while the pre-war

legal framework concerning urban growth management, inadequate and incomplete, was

not immediately updated.

It was for this reason that after the Second World War the issue of the protection

of urban landscape and cultural heritage was inextricably intertwined with that of

the public management and control of the land. The protection issue no longer concerned

just individual archaeological sites or monuments, but also the surrounding contexts,

entire minor heritage sites—that is, those areas that would soon be in the national

and international spotlight.683 At the same time, the scientific debate widened its spectrum of those areas of urban

landscape and cultural heritage considered to be worthy of protection, from outstanding

areas to other parts of the region, both natural and manmade, which were previously

unprotected simply because they were not subject to threat.

Between the fifties and sixties, the so-called reformist urbanism developed in Italy, the main aim of which was to reform the national framework of

urban and regional planning. The main advocates of this trend devoted much of their

work to this, which involved not only drafting plans, but also communicating regularly

with local stakeholders. Through the effort of explanation and disclosure of planning

principles, with an attitude that can best be defined as pedagogical, the reformist

urban planners took it upon themselves to overcome the elitism of conservative discourse

and called the citizens’ attention to local government as a moment of political democratization.

Relationships between urban planners and local governments were characterized throughout

the whole of the Golden Age by complex dynamics that were often conflictual in nature.

The former based their projects on an advanced debate that had developed within the

INU (the National Institute of Urban Planning) around two key subjects: public control

of urban development and the protection of historic centers. The latter were susceptible

to pressure from local interests, primarily those of construction entrepreneurs for

whom many people worked, especially in areas where other industries were poorly developed.

In general, across the country, from the Reconstruction onwards, construction was

considered to be a driving sector of the economy for its capacity to stimulate the

more traditional forms of manufacturing and to employ low-skilled workers. Throughout

the fifties an atmosphere of great tolerance towards urban abuses and disorder prevailed.684

In this respect, both Catania and Syracuse are exemplary cases of the uneasy interaction

between technical and political aspects due to two important figures in national planning

who were around for a long time: the old Luigi Piccinato, founder of the INU, and

the young Vincenzo Cabianca, one of a new generation of planners who, under the guidance

of Adriano Olivetti and Giovanni Astengo, viewed urban planning as a social science

and threw himself into reforming the sector. The work of the INU produced a concrete

result only at the end of the sixties with the enactment of the Mancini law, also

known as »the bridge law« (Legge Ponte, Number 765 of 1967) as it was supposed to provide transitional regulations towards

a more complete urban reform that never actually materialized. As we shall see shortly,

the law established a major break with the previous period, a factor that significantly

changed the rules governing the building of urban spaces.

In Catania, and even more so in Syracuse due to the drive of Cabianca, the constant

exchange with stakeholders sought by the reformist urban planners through frequent

press reports, dedicated meetings and public debates contributed to raising awareness

of the cultural values of heritage and the local landscape. Especially in the case

of Syracuse, the explicitly educational purpose of the dialogue with the citizens

stimulated and consolidated the processes of patrimonialization that would support

the battles of the seventies, bridging the gap between a minority »party for protection«,

whose members were elitist and cultured, and a »development party« that appealed to

large segments of the urban population.

The Conflict Between Protection and Development: From Elitism to the Idea of Heritage

and Landscape as a Right

The conflict between modernization and economic growth, on the one hand, and safeguarding

values, cultural heritage and landscape, on the other, is one of the dominant issues

in Italian postwar history. It has given rise to a narrative that literature and cinema

have conveyed and fixed indelibly in the collective memory. At the basis of this story

is the harsh condemnation of the damage done to national treasures, a powerful narrative

first found on the pages of the weekly Roman magazine Il Mondo. Antonio Cederna began a new narrative genre in this magazine with his famous tale

of the sack of Rome by the new Vandals. In this tale, the urban transformation of

the capital, the archetype of all Italian cities, is represented and interpreted as

the result of speculation and corruption in a language that mocks the poor taste of

the »new barbarians« for their ignorance of the past, of history and art, and their

sad middle-class view of the world.685 The voice of Cederna, in the minority elite battle for the preservation of heritage

and the national landscape, dominated the fifties, the decade in which—in contrast—the

national political class adopted a very lenient line towards building initiatives

in an atmosphere of poor control of market dynamics and blatantly weak public intervention.

As I have pointed out, however, the postwar period also opened up a phase of great

renovation of the Italian urban planning culture, encouraged by the heated debate

that took place within the INU and on the pages of the journal Urbanistica, the aim of which was not only methodological renewal, but also social legitimacy

of the discipline. Between the fifties and sixties, this debate produced two major

policy documents: the Town Planning Code and the Charter of Gubbio.686 The former put forward radical proposals for the revision of the legal framework,

targeted to allow public control of land and the income from it so as to promote urban

growth in the public interest and respect for the landscape and cultural values. The

other aimed to spread a culture of the historic center as an organically complex whole,

consisting of imposing monuments and more modest surrounding areas, giving rise to

a planning policy that could overcome the passive and selective nature of the traditional

constraints. These documents, drawn up at a delicate time of change in the political

balance in the country, formed the basis on which the architects and urban planners

began a dialogue with the representatives of the new political alliance between Christian

Democracy (DC) and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) in the years of the so-called

»center-left« (from the early sixties onwards). The sixties were dominated by this

tension of urban planners in an exchange with politicians, on the one hand, and society,

on the other, and it ended with a third important document of a less theoretical nature

than the first two, but equally programmatic in nature: Progetto 80 (1969),687 an ambitious program of territorialization of national economic policies in which

the theme of the cultural and natural heritage of Italy was directly linked to the

issue of development models and their compatibility with conservation objectives.

The new element, which formed a link between the years of the center-left and the

seventies, was the notion of heritage and landscape as a »right of citizens« to culture

and leisure. It was a prelude to the more explicit claims of decentralization policies

for the cultural heritage characteristic of the seventies, in the name of a principle

of democratization of culture.688

The Sixties as Incubator of the Turning Point. Three Key Points of the Change

The two cases discussed here reveal a stark difference in the material outcomes of

the conflict (Syracuse faced the threats more successfully than Catania where they

led to the disappearance of vast portions of the old town and the devastation of suburban

landscapes). They also show a discontinuity between the time of the so-called »centrism«

(from the late forties to the early sixties), characterized by the government of the

DC, which was in power in the Sicilian cities as well, and that of the center-left

both on a national and a local level.689 This discontinuity points to a more careful periodization of the three postwar decades

and helps to understand to what extent the origins of the innovations of the seventies

lie in the previous decade, even in their nature of rupture.

The new center-left political experience heralded a new conception of the role of

the public in the governance of urban processes and the safeguarding of public interests;

during this time the politicians began to take interest in the culture of national

urban planning that had an unprecedented opportunity in the new political climate.

The »Reform of Urbanism« constituted one of the main key points of the program of

the new governing coalition. The sixties was a time of fervid urban planning when

the planners spent a long time in the cities they were working on; the »technical

aristocracy« of the planners often resulted in a firm commitment to disclosing the

principles of reformist urbanism to the citizens.690 From these lengthy exchanges between experts and local stakeholders important new

elements emerged only after collective protests at the end of the decade contributed

to clarifying and expressing those elements in a more organized form. The particular

nature of this dialogue between experts and citizens established during the sixties

influenced the presence and status of urban heritage in the debates and protests of

the seventies.

The cases studied, with their differences (due to significant diversities in cultures

and urban identities in the long-term, and in the strategies implemented by local

political forces, both those in power and the opposition), show the sixties to be

an incubation period for some innovations that fully developed at the beginning of

the new decade and marked the seventies as years of great change.

I will focus on three key aspects of the protection/development dialectics that indicate

a turning point in the seventies:

The way of building urban spaces changed radically following the urban reform introduced

by the Mancini law (1967–68) that altered the relationship between politics and business.

From the seventies onwards, the urban development rules became the basis of a new

covenant in which a new subject entered: organized crime that raised its ugly head

in Catania in particular.

The issue of the protection of historic centers arose from the debate among the experts

on the subject and became a matter of general interest: with the ferment of mass protests

the battle took on clearer social connotations and political topics such as »participation«

and »decentralization« became part of expert discourse, producing innovative governance

guidelines.

The subject of the protection of the landscape went beyond the historical and aesthetic

dimension and began to involve environmental issues; a new awareness of the ecosystem

arose in the public discourse on protection; this also emerged from the growing perception

of the negative impact of industry.

The same factors of innovation occurred to varying degrees in Catania and Syracuse,

producing different outcomes and sometimes even opposing ones, in relation to the

economic structure of the two cities, on the one hand, and the physiognomy of cultural

identity in the long term, on the other.

Comparing Catania and Syracuse: Economy, Culture, and Politics

Catania and Syracuse are both in the eastern region of Sicily. Both cities belonged

to what the economist Paolo Sylos Labini described in 1965 as the most modern part

of Sicily: a land not yet affected by mafia crime, characterized by more modern agricultural

production and greater economic and social dynamism.691

From the early fifties, this area benefitted from grants from the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno, which were more strongly oriented to industrial development after the 1957 reform

law. Therefore, both cities had their industrial development zones (ASI) which, however,

were characterized by radically different productive sectors and sizes of businesses.

Angelo Moratti set up Rasiom in Syracuse in 1949 and began the long era of petrochemical

development which would see the arrival of Esso and Montedison in subsequent years.

In Catania there were mechanics, food and manufacturing industries (wood, furniture,

ceramics, sanitary ware, and plastics—largely generated by the building sector) characterized

by small production units mostly of local origin.

There was a strong construction industry in both cities. It was a sector of transition

from under-employment to full employment and throughout the fifties it consisted mainly

of small to medium-sized businesses with semi-skilled and unskilled workers. Active

construction companies in the two cities in Sicily between the fifties and sixties

operated in a particular way which allowed entry into the market for people with little

or no availability of capital: the exchange mechanism, permuta, through which contractors reimbursed the landowners »in-kind« with apartments.

By and large, this mechanism regulated micro building operations on small or very

small lots, sometimes within residential urban voids and unused small spaces, and

generally following a system of replacing a pre-existing building with a much larger

one: owners of properties of small value (but also the wealthy owners of the splendid

Art Nouveau villas in Catania) yielded lots and allowed the building to be replaced, thereby

becoming owners of apartments with access to a thriving rental market; on the other

hand, small and very small building firms could participate in the building venture

for a modest initial investment. The social advantage was an employment demand commensurate

with the needs and supply of the local market, widespread financial improvement that

was well distributed among the population and an answer, albeit selected and dictated

by private interests, to the urgent demand for houses.

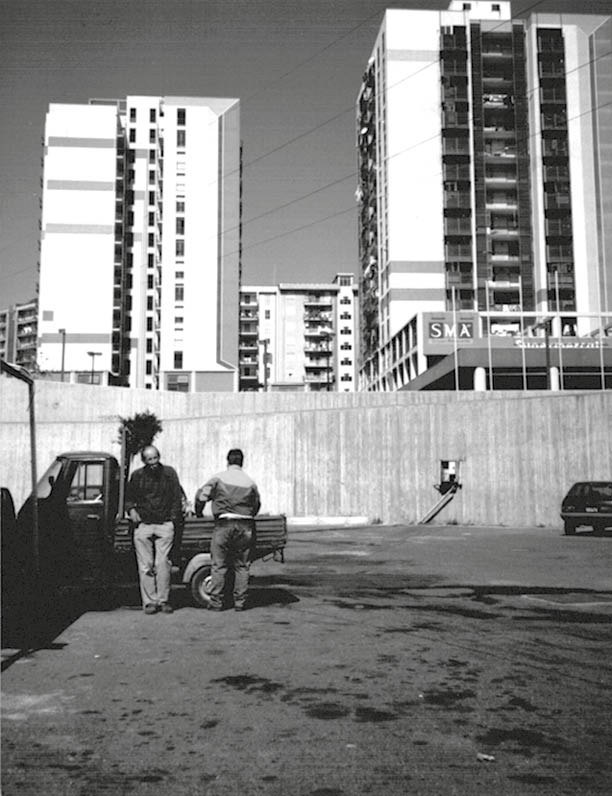

Both Catania and Syracuse saw their populations grow tremendously in the fifties and

sixties, swelling with people from the provinces.692 Catania came from a tradition of great exchange and openness to the province, with

many small and medium towns that were relatively thriving both economically and socially,

whereas for Syracuse and its ruling class the »invasion« of people coming mainly from

the surrounding country was a new and traumatic event. The great attraction was the

industrial pole north of the city center, and the areas that lay between the consolidated

city and the industries became the preferred places of settlement of a population

that formally resided in the city but had turned its back on Ortygia, the historical

part of Syracuse whose myths and rituals they did not know; nor were they aware of

the urban identity of Syracuse as a city of art and history. The life of this new

population, whilst still depending on the traditional center for administrative and

commercial services, was developed between the new working-class and middle-class

suburbs and the industrial center while the delicate network of medieval Ortygia,

unsuited to new urban functions, became the subject of ambiguous hypotheses of renewal

and modernization.

The idea of redevelopment, still present in many of the reconstruction plans formulated

immediately after the war, was often associated with the late nineteenth-century »sanitary

approach« based on hygienic ideas to avoid contagion, which involved demolishing very

old, tightly built neighborhoods and replacing them with wide, elegant avenues; this

notion had been taken up and implemented during the fascist regime. After the Second

World War, the argument for demolition of medieval systems for the purpose of modernization

and the struggle against social deprivation was strengthened by the perceived need

to adapt to traffic requirements and new living standards.

Faced with the problems posed by the postwar reconstruction and development, the administrations

of the two cities adopted opposite strategies: Catania proceeded to an adaptation

of the 1932 plan, led by a committee of notables and implemented by municipal technicians,

while Syracuse started a new planning process from a national competition in 1954,

eventually entrusting the task to the group led by Vincenzo Cabianca. The man who

pushed for this far more enlightened choice was undoubtedly the then Superintendent

of Antiquities for Eastern Sicily, the archaeologist Luigi Bernabò Brea, follower

of a prestigious tradition of international figures of scholars active in Syracuse

since the eighteen-eighties. Bernabò Brea, a respected member of the board in the

competition, became the inspiration for a strategic vision in which the archaeological

urban heritage and its monuments scattered around the city became the cornerstone

of the future urban project that portrayed the system of the historical and archaeological

sites as »a great tourist-cultural infrastructure«. From their first meeting until

Bernabò Brea was withdrawn from office in the mid-seventies, the relationship between

the archaeologist and the young urban planner Cabianca, which soon turned from collaboration

to close friendship, was based on a shared, informal but firm commitment to the continual

connection between urban planning and environmental protection.

There was a completely different scenario in Catania where, at the same time, thanks

to the activism of a part of the DC connected to the Roman building society Immobiliare

Generale, the so-called operation San Berillo suddenly took place. This operation

was carried out through the establishment of two private companies: the IstBerillo,

aimed at the construction of a lower-class neighborhood on the outskirts of the city

to house the old inhabitants of the historic district San Berillo, and the IstiCa,

designed to carry out the demolition of the historic district and the construction

in its place of a very high-density business area. It all happened quickly under the

incredulous eyes of the people of Catania and the silence of the Soprintendenza ai Monumenti della Sicilia Orientale, which had its headquarters in Catania. Protected by a special regional law, the

project IstiCa established land-density standards that would influence the future

of urban planning processes in Catania, keeping the value of the land high, as declared

by the urban planner Piccinato.693 Also in Syracuse, following the example of Catania, a part of the local Christian

Democrats made a proposal for a special law that, relying on the same arguments that

had supported the operation San Berillo (social degradation of the neighborhood as

an old prostitution center), proposed the demolition of the Graziella district in Ortygia. It was a proposal strongly opposed by scholars and intellectuals

who, under the moral leadership of the Soprintendente alle Antichità Luigi Bernabò Brea, defended the integrity of the old town several times; this was

the preparation for the plan launched by Cabianca in 1956.694

Although the decades of prosperity in both cities represented a clash between protection

and development, the attitudes of the ruling elites and local politicians in the interpretation

and debate around this topic were quite different.

After the Mancini Law: A New Way to Create a City

In Catania, the interaction between the Communist Party (PCI) and the DC in the years

of intense urban growth took on a more pliable aspect than in Syracuse; while the

public discourse reflected the content, language and tone of the national debate,

what actually happened was that the local PCI tended to vote for measures that compromised

the integrity of the historic center and many sites of landscape value during the

thirty years after the war. The IstiCa project of San Berillo at the beginning of

the fifties had been unanimously approved of by the city council; similarly, widespread

amnesties for land use violation on payment of a fine were unanimously deliberated,

which closed the »golden age« in 1969–70.695 The diverse structures of the construction industry in the two cities influenced

this. In Catania, not only did it provide the majority of jobs in industry, but the

workers were the most unionized. ANCE (the National Association of Builders) was as

active in Catania as were the workers’ representatives, and both of them were particularly

concerned about the restrictive measures for construction. On the contrary, the PCI

in Syracuse found most of its voters in the field of the petrochemical industry, which

urged them to concentrate their battles on getting social housing and challenging

the political party in power more freely on the issue of urban planning and the protection

of the city’s cultural heritage.

A substantial part of the political debate in the second half of the sixties concerned

the effects of the Mancini law, a result of the reformism of the center-left. The

law Number 765 of 1967, which was enacted at the end of a tormented debate on public/private

balance in the building of the city, introduced important innovations: the charging

of infrastructure costs to the owners, the obligation of detailed plans, the almost

complete limitation of individual licenses and the establishment of quite large zones

called comparti edilizi, known by their buildings that had to be built in a homogenous way (concerning facades,

height etc.), with the agreement of all the owners. All these measures meant that

many construction companies were forced out of business and only large developers

with large amounts of capital to invest survived. The town plans that Piccinato and

Cabianca delivered to the administrations at the end of the decade, which prioritized

functional aspects and large scale zoning on a regional level, indicated the change

of scale that characterized the building of new urban spaces in Italy between the

sixties and seventies with its inclination towards gigantic infrastructure, with urban

highways, major business centers and the concentration of residential zones in the

New Town in areas where traditionally urban development did not take place. On the

political and academic level, the principle of »correcting imbalances«, which inspired

modern economic and planning theories and which was affirmed with the famous Nota Aggiuntiva (1962) by Ugo La Malfa (a true manifesto of the center-left), supported these changes.696 However, the underlying theory that inspired the Nota was not unique to Italy, but reflected the thoughts that were developing in the young

European Economic Community. From an academic perspective, regional planning strategies

were aimed, therefore, at what Manfredo Tafuri effectively defined as »the rebalancing

myth« because of the often utopian nature of plans and projects that arose in the

late sixties.697 They aimed to create urban attractors on a regional scale in order to boost construction,

especially of homes, and to counteract urban sprawl. For this reason, the New Towns

designed for Catania and Syracuse as integral parts of plans at the end of the decade

represented safeguarding tools for the landscape defenders: by polarizing and densifying

the town into designated areas, the planners of the New Towns pursued their aims to

save precious suburban landscapes (hilly and coastal) from the threat of urban sprawl

and mushrooming expansion.

The political debate around the Mancini Law and the implementation of the New Town

(the sheer size of which threatened to drain all urban resources and finances) was

equally intense but had opposite effects in the two Sicilian cities. In Syracuse,

the Christian Democrats tried to safeguard the old way of building urban spaces: individual

licenses, exchange of land for property, and small and medium-sized enterprises. While

in Syracuse the PCI fought for the construction of the »linear city« designed by Cabianca,

which envisaged the establishment of a New Town in the South, the ruling Christian

Democrats scuttled the project.698 In Catania, in contrast, the increased level of organization of the construction

industry pushed the local Christian Democrats to make the Mancini Law the basis of

a new, more evolved speculative business. Unlike what happened in Syracuse, some prominent

members of the Catania Christian Democrats fought for the construction of the New

Town of Librino that, with its large residential size and infrastructure, the impressive

labor-intensive public works which constituted an essential requirement and through

a vast system of tenders, became an aspiration for the privileged entrepreneurs who

had emerged from the cauldron of the fifties and sixties—after the ruthless selection

induced by the new law. These were the so-called cavalieri del lavoro of Catania, a small number of local construction companies whose links with the Mafia

were to emerge in the eighties after the sensational murder of journalist Giuseppe

Fava, who investigated the relationships between construction companies, politics

and the Mafia.699

The intervention of organized crime, which exploited the great building companies

in order to launder money and manipulate the job market, became part of the new pact

between politics and construction. Because of this, the discontinuity with the past

that marked the seventies was radical; this fact is often overlooked because of the

indiscriminate use of the term »building speculation« in subsequent interpretations

of these processes, interpretations that not only homogenized the entire three decades

of the Golden Age, but also assimilated the following years to that period. This assimilation

did not foster a deeper analysis of these processes nor an understanding of the changes

in the production of urban spaces or of the attitude of the political class, whose

decisions have been indiscriminately interpreted as an effect of corruption and even

of criminal intent.700

The Statute of Historical Heritage in the Age of Protest

It was not only the structural data of the urban economy that pushed the Communist

Party of Catania towards a much softer line regarding the housing mess and resulting

damage to the cultural heritage and landscape of the city. There was also a cultural

component that Giuseppe Giarrizzo has discussed and reiterated in his long reflection

on the history of Catania as a disconnection between politics and urban culture.

In Catania, reformist urbanism was well represented in the University’s Faculty of

Engineering and it addressed the issue of urban transformation: the focus of the debates,

often high profile, was the topic of land rent; much more rarely did it touch on the

issue of the conservation of the historic urban landscape, which in those years was

changing rapidly. The discussion on the management of urban transformation was, however,

largely confined to academia and in the debate between technicians and academics,

with scant ability to penetrate local politics and society.

On the contrary, due to its strong tradition of historical and archaeological studies,

the Soprintendenza alle Antichità of Syracuse became a reference point for a cluster of small cultural associations,

initially set up by an elite group of intellectuals, local and otherwise, then by

educated middle classes and finally by groups of young people who had learnt the importance

of protection also thanks to the bond that the previous generation had developed with

national associations, particularly with Italia Nostra. Without a specific academic dimension, the debate on the transformation of the historic

urban landscape of Syracuse ended up penetrating local society and engaging in politics

more directly than in Catania. The question of the future of the historic center quickly

polarized public opinion around two alternative positions, both capable of mobilizing

the participation of citizens, especially starting in the late sixties when the problem

of the depopulation of Ortygia became more evident. The proposals to modernize were

made by an ambiguous »pro-Ortigia Committee« led by the owners of grand buildings

that had dropped in value due to increasing dilapidation, but also by a number of

professionals; on the other hand, the so-called Gruppo Archeologico, led by young Syracusans who were cultured and on the warpath, quickly objected and

carried out a tireless awareness-raising campaign against the destruction and demolition

projects. On the cusp of the sixties and seventies, at the same time as the launch

of Cabianca’s second plan (1970), local non-academic professionals and ordinary people

formed the Centro di Studi Urbanistici (Urban Studies Center), of which the explicit purpose was to inform and involve citizens

in land use decisions of the administration.

This difference between these two cities in their sensitivity towards the change in

the historic landscape marked the spell of the age of protest. In Catania, most of

the protests were held by (mainly humanities) university students. The arguments debated

by students and young intellectuals of the left were well-developed and closely linked

to the national network of mobilizations, but at the same time they had a strong ideological

connotation with an intellectualist orientation, on the one hand, and an ideological

attention to the working class, on the other; however, they had a very tenuous connection

to the physical urban heritage, with the exception of some groups of the Catholic

milieu, which was heavily hit by protest and internal generational opposition in Catania.

Overall, the people of Catania watched collective movements from afar and prepared

for the »black vote« of 1971–72.701 In the seventies the process of abandonment and decay of the historic city intensified:

it would reach its peak in the eighties, when the depopulated eighteenth-century city

center remained at the mercy of petty crime while services and businesses moved further

and further north in the twentieth-century expansion areas and the radius of urbanization

invested the hilly wooded area on the slopes of Mount Etna, compromising the landscape

forever.

The only thing that went against this tendency was the start of the restoration of

the monumental complex of the former Benedictine monastery. The project got underway

in the first half of the seventies on the initiative of the Catania city council.

It would result in the redevelopment of a vast inner-city lower-class area (corresponding

to the old neighborhood of the Antico Corso and in part to the neighborhood of the Angeli Custodi). The Council discussions of that period, as well as the minutes of the subsequent meetings

with the University, clearly show that the plans arose because the city council needed

to dispose of an asset whose maintenance had become overly burdensome for the municipal

coffers.702 The divestment proposal sparked an internal debate at the University which at that

time was investing significant resources in the construction of the Cittadella Universitaria (university campus) on a hill to the northwest of the city, where it was initially

planned that the Faculty of Humanities would be decentralized and in a modern building

for which lavish regional funding was already available.703 When the initial misgivings had been overcome, the long journey to return the Monastery

to the city was completed in 1974 when the Council sold the property to the University

for the symbolic price of one lira.704 In 1976 the Faculty of Humanities celebrated the start of the gradual transfer to

the Benedictine Monastery with a party whose playful poster represented this historic

architecture in which fragments of the work of Le Corbusier were hidden with a clever

photomontage.705 The relationship between the neighborhood and the University was tense for a long

time, and there was no shortage of moments of conflict; however, the restoration of

the Benedictine Monastery soon became an ambitious cultural project of the University

that, in 1978, would bring to Catania such important architects as Piero Sampaolesi,

Roberto Pane and especially Giancarlo De Carlo, who played a vital part in the work.706 Giuseppe Giarrizzo, who was Dean of the Faculty of Humanities for many years, initially

doubted the decision of the Rector Sanfilippo to restore the Monastery. Instead he

wanted the Faculty to be in the Cittadella Universitaria (as funds were available for it). He correctly foresaw that the process of regeneration

of the complex and its surroundings would be long and difficult. However, once the

decision was taken, and until the end of his life, Giarrizzo became one of the main

actors engaged in the Monastery’s restoration against the indifference of the citizens

and often the hostility of the city’s institutions. Years later, the director of the

Technical Office of the University would effectively sum up the situation by saying:

»We could do so because the people of Catania were distracted …«.707

On the contrary, in Syracuse, a smaller and more provincial city, the new decade began

in a climate of participation and decentralization. This was due to Cabianca’s ability

to make people reflect on the future of Ortygia in an open exchange with the politicians,

the administration, political parties and citizens regarding the local historical

and archaeological culture. There were political protests but the youth of Syracuse

were much less violent and ideological than those of Catania, and there was a lower

generational conflict within the political arena that often led young Syracusans to

cooperate with representatives of the traditional parties rather than to assume positions

of rupture. The most active representatives of the local civil society took the historic

center as a key theme in the demand for democratization, specifically looking at the

restoration model of Bologna’s historical center where the preservation of the residential

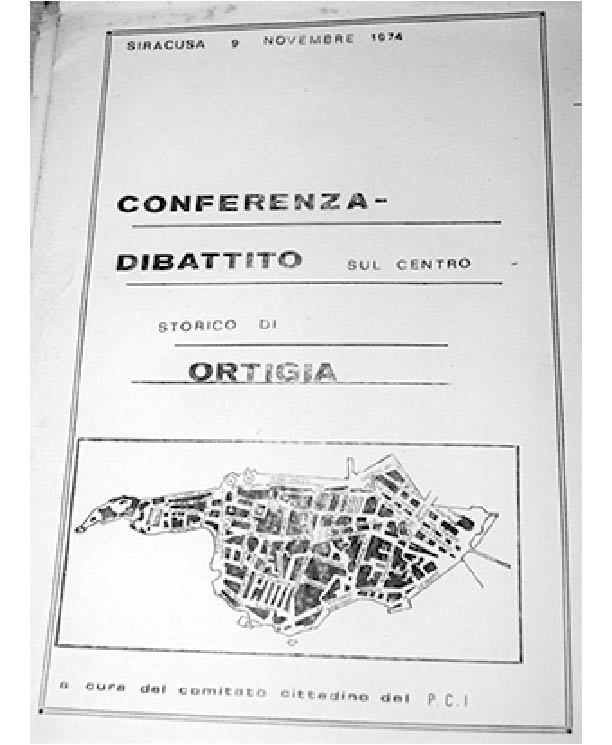

areas and the protection of the most vulnerable groups were significant elements.708 The reference to the Bologna model was not exclusive of the Syracuse leftist groups:

that model was also taken up by large transverse portions of the urban ruling class.

Both mainly focused on the social strategy aimed at maintaining original residents

in the historic center, rather than the typological and morphological choices. The

Bologna model was examined and debated at a major conference on the future of Ortygia

organized by the PCI in November 1974,709 but also, significantly, carefully studied by a delegation of representatives of

public bodies, trade unions and employers associations and journalists, who paid a

visit to Bologna in March 1974 on the initiative of the Syracusan municipal tourism

agency.710

In the climate of lesser political conflict that characterized the situation in Syracuse

and which moved towards general agreements between the DC and PCI in the middle of

the decade, it was on the issue of the historical center that the two main parties

found an important point of convergence at the end of a period of intense public debate

through cross collaboration among the regional councillors from Syracuse on a regional

law for the protection of Ortygia.711 The law was approved by the Sicilian Regional Assembly in its session of 28 April

1976. This was an advanced law that followed the principles of the charters of Gubbio

and Venice. It established the extended principle of restoration as a means of intervention

on minor environments, excluding any hypothesis of mass demolition. In addition, ample

attention was paid to the social dimension of the problem, focusing on the citizens’

right to live in the historic center and the need to combine protection of the architectural

and monumental heritage with access to services and maintaining traditional productive

functions, with a view to exploiting the local neighborhood councils, which were being

set up at that time as a result of political demand »from below«.712

The Idea of Landscape: From Functionalism to Ecology

In Syracuse, the petrochemical complex and the appearance of the first pollution problems

at the end of the sixties, giving a clearer perception of the connected health risks,

contributed to a deeper and more widespread awareness of the importance of environmental

protection. This was something new. During the public debate of the sixties the problem

of preserving the landscape had been discussed in terms of the preservation of its

aesthetic, historical and cultural qualities. The public discourse that accompanied

the long planning process had been characterized by the importance of the role of

»green space« in the urban system, according to the prevailing view throughout the

sixties also present in Progetto 80, the only experience of national town planning in Italy in which Cabianca participated

directly.

An exemplary case of how this concept changed over the seventies are the projects

for the coast of Syracuse, in general, and the area of the salt flats of the river

Ciane in the area south of Syracuse, in particular. Cabianca’s project for the area

of the proposed salt flats at the end of the sixties involved the construction of

a marina that could accommodate up to 1,000 boats, »with a predominance of large and

medium sized vessels«; it was to be equipped with »a sufficient number of complementary

services«; a second landing, for yachts and other leisure crafts was expected further

south in a place called Sacramento.713 This project did not take into consideration the environmental features of the coast

of Syracuse. It was lacking in any awareness of the potential impact of tourism activities

(generally mass activities) on the delicate natural system of the mouth of the Ciane,

in which the role of the salt flats was fundamentally to act as a protection. The

way the landscape was dealt with in the new Syracuse plan was consistent with the

underlying sensitivity to Progetto 80: green space was seen as a rebalancing of the dysfunctions of urban and industrial

systems from a functionalist perspective, but an analysis of ecosystem relationships,

or an exact survey of sensitive areas (for example, the recognition of wetlands as

biological stations) were entirely lacking. Tourism, even in the case of seaside tourism

and mass tourism, was seen as a productive function that was absolutely compatible

with the objectives of protection. The landscape evoked in the project description—the

landscape for which intellectuals and Syracuse associations fought—was still without

doubt, despite the emergence of new elements, the beautiful scenery, the »framework«

evoked by the law of 1939.714 To understand the massive amount of transformation that was expected near the mouth

of the Ciane, with the approval of what might be called the party of protection, comprised

of intellectuals, scholars and associations of citizens, we only need to think that

the marina designed by the project team would have had to be equipped with »piers,

docks, pier moorings, columns with access to water supply, electricity sockets, telephones,

etc«.715 The same magnitude characterized the plans for sports facilities to be built in the

large regional park. A sports city was to be constructed »on the left of the Ciane

and Anapo rivers« to house facilities for shows and competitions and complementary

facilities for the training and care of the athletes or services for the spectators.716 Just a decade later, the citizens’ associations, including the local branch of the

WWF, would campaign against the marina project for the salt flats and for the establishment

of nature reserves in the wake of a campaign for the protection of the Sicilian coastal

wetlands and the shock caused, in 1977, by the sudden blight of the Ciane papyrus.

The campaign was based on a vision of the natural landscape that now incorporated

the debate on sea pollution that had arisen from conflicts in the industrial area,

the idea of the environmental media and an ecosystem-based vision of the territory.717 This more developed form of environmentalism, which became more widespread in Syracuse,

depended undoubtedly on the devastating environmental problems in the industrial area;

a critical step, in 1975, was the protests of the inhabitants of the village of Priolo

against the construction of a new plant for the production of aniline. Such protests

reached moments of high tension and led to the administrative separation of the Priolo

area, a fact fraught with consequences for the city of Syracuse, which lost administrative

control over the industrial pole.718 However, the constancy with which the urban planner Cabianca had worked as a mediator

between the urban culture of conservation (prestigious, connected to the national

network, but elitist) and the citizens contributed to the development of awareness

of the new environmental problems. A clear example of Cabianca’s engagement in the

construction of a shared consciousness about the urban landscape and cultural values

and their role as common goods and strategic resources, was his broad dialogue with

local stakeholders during the intensive Prima conferenza dei servizi sul piano regolatore, a widely participated urban conference about the development of the territory and

the new plan strategy held on 25 and 26 October 1968.719 Launched by the local administration and directed by Cabianca himself, the Conference

represented an important step in the definition of a shared strategic framework for

the future of Syracuse in which the topic of natural and historical urban landscape

emerged as a pillar of the new city. The 1970 plan, widely debated in many political

and cultural venues, outlined a development model in which the preservation of the

quality of the historic urban landscape, coastal areas and cultural heritage was a

central aspect and certainly formed the basis of a more aware environmentalism in

the decades to come.

In Catania, in the mid-seventies, once again it was the University that denounced

the excessive environmental costs of development with an analysis of the environmental

conditions of the urban system conducted by the Institute of Architecture and Urban

Planning (IDAU) and published in 1975. It highlighted the impact of unregulated and

unbalanced growth. As early as then, the most problematic environmental issue was

identified in the traffic system and the absence of an adequate public transport network.

However, the citizens of Catania were distracted by other problems, including the

»southern suburbs« comprised of the young New Town Librino, which soon reached the

same levels of degeneration as the historical districts; consequently, they protested

more readily on purely political and social issues rather than on the environmental

problems which are still pressing to this day.

The comparison between Catania and Syracuse shows that in both cases the seventies

represented a turning point determined by the economic decline itself, which attenuated

the anthropic pressures on the historic urban landscapes by the legislative changes

that closed the previous decade and by the new national and international guidelines

that inspired the new projects on cultural heritage and landscape. Nevertheless, the

scope of the breakthrough varied considerably from one city to another. Some differences

are due to long-term urban cultural identity and the different structure of the urban

economy in each city. Other important differentiating factors emerged in the course

of the urban planning and development processes and in the kind of public debate that

had taken place during the previous decade: the sixties can therefore be defined as

an incubation period for the turning point. One important factor was the nature of

the interaction between the two main parties, the DC and the PCI. An additional factor

was the constant and intense interaction between reformist planners, politicians and

local society in Syracuse. Finally, the attitude of urban cultural institutions and

their attention to the planning process played a decisive role. The cultural leadership

of the Soprintendenza alle Antichità also played an important role by continually pushing through crucial public interventions

so that heritage and the historic urban landscape would constitute the core of the

urban project. The Soprintendenza ai Monumenti di Catania took a different attitude, limiting itself merely to the bureaucratic function of

surveillance and sanction. This deficiency was only partially remedied by the University,

which had a much weaker role in guiding public opinion than the Soprintendenza alle Antichità in Syracuse, in part due to the different size of the two cities; however, it succeeded

in handling the complex restoration project of the Benedictine Monastery that over

time would prove to be a strong point and a model for the enhancement of urban heritage.

In both cities, the areas saved from degradation and destruction in the seventies

were given a boost in the nineties through the Joint Initiative Urban Programs funded

by the EU when the huge project of restoring the historic centers of the two cities

began.720