The Struggle for Housing in Rome. Contexts, Protagonists and Practices of a Social

Urban Conflict

Luciano Villani

A protest movement centered on the housing problem was among the most significant

components in the fierce social conflicts that characterized Italy in the seventies,

a period when unrest triggered by housing and urban organization issues escalated

in all major Italian cities. On a national level, however, it is safe to say that

Rome stands out as the most representative and extended case of social conflict taking

place in a widespread manner throughout the city to such an extent that the urban

struggles occurring in the capital could be said to be tantamount to the workers’

struggles in the big northern industrial hubs.840

This chapter aims to reconstruct the social and political context in which the struggle

for housing in Rome developed in the first half of the seventies. In this period,

the housing problem caught the attention of a wide range of social actors, and catalyzed

mass participation in the political life of the city. Having critical problems, the

suburban areas of the city proved fertile ground for the development of a variety

of protest groups: tenant associations, Catholic dissidents, housing campaign groups

and neighborhood committees, most of which were established to meet local needs and

were therefore able to achieve large consensus among the inhabitants of the most deprived

areas and to respond to the significant demand for direct participation in democracy

coming from substantial sectors of society. In the same period, the traditional approach

to campaigning for social housing was called into question. The practice of direct

social action began to be used and this in turn generated new campaign repertoires

that were then adopted. On an urban level, the social conflict saw militant resources

put at the disposal of the revolutionary left-wing organizations. These groupings,

which had come together around slogans, social practices and debates on radicalization,

were subject to intense political infighting and partisanship, which caused further

divisions.

This study aims to assess the impact that this cycle of protest about housing had

on the development of the city as well as to give some understanding of the legacy

of experience and controversy left by the urban social movements which came on the

scene during this challenging period. It also highlights the way in which the authorities

dealt with some of the most turbulent times. Finally, attention is turned to contextualizing

places since the particular social and environmental situation found in suburban areas

and the construction of a collective identity based on belonging to a specific area

make the Roman experience different from that of other cities.

Tradition and Innovation in the Struggle for Housing in the Early Seventies

A social movement with a strong local presence had already made an appearance in Rome

in the aftermath of the Second World War, when the Consulte popolari (Popular Committees) began their political and organizational work in the suburbs

of the capital. These were activist groups connected with the PCI (Italian Communist

Party) whose aim was to give voice to residents in the poorest areas and to bring

their demands to the attention of the authorities. Since then, thanks also to a particular

model of economic and urban development, the embarrassing presence of shantytowns

and a public debate centered on property speculation,841 the housing issue had become the main arena for social conflict and it was to remain

as such in the following decades. A quarter of a century later, in fact, despite the

proliferation of political initiatives and the introduction of a string of legislative

measures, tens of thousands of people continued to experience extremely poor housing

conditions, including cramped and temporary accommodation in official borgate, illegal borgate lacking all basic services, overcrowded hostels, dormitories full of people living

in poverty and shantytowns with a population of approximately 60,000 inhabitants that

sprang up spontaneously throughout the entire city.842 In 1970, a century after the Capture of Rome, left-wing organizations provocatively

decided to enact a demonstration in celebration of Rome as »the capital of shantytowns«

rather than pay tribute to the centenary of the city as the capital of Italy.843 The struggle for housing had dominated the sixties and reached a dramatic climax

in 1969 thus adding to the waves of general protest affecting the country. In the

summer of 1969, a renewed squatting movement came on the scene. It was no longer controlled

by UNIA, Unione nazionale inquilini assegnatari (National Tenants’ Union, an association that had taken over the Consulte in 1964) but by CAB, Comitato Agitazione Borgate (the Shantytown Agitation Committee). Their members were Catholic students, PSIUP

(Italian Socialist Party of Proletarian Unity) party militants and communists critical

to the PCI and they all campaigned in urban ghettoes alongside the inhabitants.844 Supported by CAB, hundreds of shantytown dwellers engaged in extensive squatting

in various neighborhoods, gaining the attention of the major national dailies.845 Squatting actions promoted by CAB were based on decisions approved by the homeless,

while the old leadership, accused of acting independently from the struggle and of

vilifying it through »premeditated agreements«, was losing its appeal.846 The most important innovation for change introduced by CAB was the intention to make

squatting permanent. Until then, the practice had been largely symbolic, and primarily

targeted social homes left empty. Squatting usually culminated in evictions followed

by political pressure on local administrations and social housing agencies in order

to find an immediate solution for a certain number of families and to place others

in emergency plans. However, few social houses were being built and, due to extremely

slow procedures, they were allocated with shameful delay.847 Consequently, there was increasing scepticism and disillusionment amongst those waiting

for a home which gave a boost to collective and individual squatting. In 1969, the

IACP, Istituto autonomo case popolari, (Social Housing Autonomous Institute) began to bring numerous lawsuits against families

that had illegally occupied the Institute’s properties.848 The idea that the only way to secure social housing was illegal occupation instead

of the exhausting wait for the completion of endless bureaucratic procedures or political

negotiations was therefore taking root and spreading—with it came a specific attitude

that justified this kind of informal practice and identified formal applications as

a waste of time.849

The period between 1969 and 1971, however, can be seen as a time of transition where

old and new practices coexisted. On the one hand, new political protagonists had begun

to position themselves within the social conflict as a consequence of the »Catholic

dissent« explosion and the massive student protests of 1968, while, on the other hand,

the organizations linked with left-wing parties were not inactive. On the night of

4 October 1969, UNIA coordinated groups of shantytown dwellers in the squatting of

three private buildings in central areas.850 Negotiations were launched whilst the buildings remained occupied. Furthermore, UNIA

managed to secure a prominent role in the legal litigation against the municipality

opened by CAB, establishing a partnership with them. Under pressure from the demands

of private owners, the authorities found it difficult to get away with unfulfilled

promises and mere repression, as they usually would, because of the central location

of the occupied areas and the climate of solidarity that was developing around those

living in the shantytowns. The center-left majority approved the proposal by the DC

(Christian Democratic Party) to acquire the houses needed to accommodate the squatters

from the market, while the idea of sequestering empty private properties, strongly

supported by the PCI but only by a single DC councillor, Cabras, was ruled out.851 By 1971, the squatters had all been moved to rented accommodation in the suburban

neighborhoods of Magliana and Ostia.852 The latter is located on the coast and thus a long way from the city. The municipality

would provide for most of the renting costs, with tenants contributing only minimally.

It is noteworthy that the same system was used in the future, thus making it the greatest

institutional concession in the face of squatting.

The agreement between CAB and UNIA generated a string of minor episodes of activism

and finally produced a surprising action: on the night of 29 October 1971, about 2,000

private properties located in various areas of the city were symbolically occupied

to demand the sequestration of 6,000 empty homes for shanty dwellers.853 In order to calm the demonstrators who had descended on Piazza Campidoglio on 5 November,

Mauro Bubbico, DC councillor for social housing, promised that 6,000 homes would be

made available by Christmas. However, on 21 December, the municipality, including

Bubbico himself, voted against the proposal for property sequestration put forward

by the Socialist Party. Shantytown dwellers took it as an insult: »The authorities

want to force them to use violence«, observed the weekly bulletin of Scuola 725, written by the students of Acquedotto Felice, a shantytown where priest Don Roberto

Sardelli had been organizing after-school activities since 1968.854 In these he gave great importance to politics intended as an instrument of knowledge

so as to bridge the gap between education and life. Although critical of the student

movement, which he judged »superficial and detached from the reality of the masses«,855 Sardelli was convinced of the legitimacy of house squatting. House squatting itself

had been described as »morally dutiful« in a Lettera ai cristiani di Roma (Letter to the Christians in Rome).856 Signed by thirteen priests in response to the 21st December’s »betrayal of the poor«,

the Lettera marked one of the most significant expressions of the dissent that lingered in the

Roman diocese—an indictment against the DC and the support it received from the Church,

which in turn was considered to be complicit in property speculation.

Positions of this kind were not new in the Catholic world. In 1970, similar opinions

concerning house squatting had been expressed by the priests of Ateneo Salesiano.857 In contrast, UNIA began to question the practice of squatting and, after the symbolic

action of October 1971, it finally renounced this form of struggle as counterproductive.

On 22 October 1971, at the end of long negotiations between the government and the

unions, bill 865, also known as »housing reform«, was approved. Although it did not

meet all expectations, UNIA and PCI considered it an intermediary step towards effective

urban reform. There was now a need to secure financing so that the bill’s most innovative

principles could be enforced (first of all the regulation concerning eminent domain)

and to prevent changes which could water it down.858 The reform was also to address the problem of accommodating shantytown dwellers,

as it included precise measures on the matter. This was also the demand submitted

by SUNIA, a national union formed in December 1972 from the fusion of UNIA and other

groups.859 Not only was the practice of squatting abandoned, it was also openly condemned by

PCI leaders and their press agencies. »This kind of struggle does not pay off«, declared

communist councillor Piero Della Seta, »it is a break-up point rather than a unifying

one«.860 The change of strategy by UNIA was soon exploited by left-wing extra-parliamentarian

groups.

Social Embeddedness and the Repertoire of Action in Urban Social Movements Development

The main extra-parliamentary groups, Potere operaio (PO) and Lotta continua (LC), tried to react to the unions’ regained control over factory workers by taking

the lead in the agitation around housing issues. At the end of 1970, the LC launched

the slogan »let’s take the city back«, while the PO tried to extend its militancy

from workplaces to neighborhoods in Rome and beyond.861 According to these organizations, the whole »social factory« had to be involved in

the conflict, whereby the more capital expanded and perpetuated exploitative relationships,

the greater the number of individuals potentially motivated to undertake practices

of »social re-appropriation of wealth« had to be. Immigrants, the dispossessed and

shantytown dwellers, all being part of the »proletariat«,862 in this view were instinctively drawn to social rebellion that could be easily channelled

to satisfy their immediate unfulfilled needs. Militant groups began to dedicate more

efforts to house squatting in 1971, a year when all actions concluded with evictions

and clashes in the streets.863 In defence of an occupation in Centocelle, the PO drew up a proper military strategy.864 Police intervention was inevitable as was the dismay of shantytown dwellers as they

were not prepared for clashes of such magnitude. Opposed by the LC,865 the PO’s imposition in Centocelle was also challenged by a group of anarchists, many

of whom were arrested that day and who blamed the PO for neglecting to conduct any

preliminary ground work in the neighborhood and for using its shantytown dwellers

as political capital.866 Similarly, the pattern of exemplary action imposed by »vanguard forces« occurred

during the occupations organized by extra-parliamentarian groups in Centocelle, Pietralata,

Magliana and Cinecittà in June 1971.867 Crucially, the lack of any ground work to build social relations became clear in

the rapidity with which buildings were abandoned by the occupants or squatters were

evicted by the police.868 In general, these events demonstrated the impromptu character of the revolutionary

Left’s influence on the capital’s suburban neighborhoods. Gradually, more sophisticated

initiatives were undertaken, based on a process of social involvement and thus were

better rooted in the communities.

This change was made possible by the fact that civil society was increasingly demanding

participation in decision making without adhering to political parties, in which public

opinion saw a deterioration that was inexorably turning the parties into »instruments

of wealth grabbing« and power grabbing,869 and in line with the activism expressed by spontaneous groups. These were the so-called

struggle committees (housing campaign groups) or neighborhood committees. While some

of them were established with openly anticapitalistic stances, they were all usually

driven by a pragmatic desire to achieve political results in terms of more services

and social improvements on a local level.870 Consequently, what followed was a period of fierce agitation characterized by growing

expectations around the issues of housing and social services, a period of increased

trust in direct democracy and the intertwining of new forms of struggle as well as

the formation of widespread social relations. Topics that until then had been considered

remote, if not abstruse, were now stimulating interest and participation on a mass

level: from urban planning to the protection of the environment, from neighborhood

redevelopment to the need for more schools, from the monitoring of public service

providers to control of the prices of basic commodities.

As previously stated, extra-parliamentary forces seemed to find it difficult to forge

durable and non-hierarchical relations with the inhabitants of suburban areas. On

the contrary, a group led by Gerard Lutte, a Belgian priest who had moved to Prato

Rotondo in 1966 to undertake his pastoral duties, was quite successful in this respect

at the end of the sixties. While Sardelli’s after-school activities in Acquedotto

Felice did not seek the support of any political or student collective because they

were centered on the strong personality of their founder instead, Prato Rotondo was

quite a different case. This was a shantytown where popular after-school activities

were carried out with the contribution of political activists and students, many coming

from the ranks of the Catholic movement. By that time, in fact, Catholics were playing

a vital role in non-governmental organizations,871 and were displaying the ability »to produce strong and durable actions« specifically

in the context of after-school activities.872 Initially a shantytown suburb, Prato Rotondo became well known for its intense political

education, by which residents, especially the youth, were encouraged to become aware

of their social exclusion. It was from here that the fight for housing rights began.873 Prato Rotondo’s inhabitants demanded houses at affordable rents, at the time 2,500 liras

per room, and these houses had to be in the same neighborhood so as not to split up

the community. After a wave of demonstrations, the municipality approved the purchase

of a number of homes in the Magliana neighborhood to be rented to Prato Rotondo’s

shantytown dwellers, who eventually moved there on 24 May 1971.874

Magliana, a south-western suburb of Rome, was a neighborhood that expanded rapidly

in the second half of the sixties. It was mostly comprised of private buildings with

a heterogeneous population (clerks, employees of the service sector and workers) of

about 40,000 people. It was built with total disregard for urban and building regulations

as it was situated seven metres below the level of the Tiber River’s embankment. It

lacked adequate sewers or social, educational and health facilities and it presented

serious problems relating to hygiene and epidemiology. Social rent prices were significantly

lower than those paid by private tenants. For these and other reasons, the shantytown

inhabitants were frowned upon by the rest of the residents. However, the difference

between social and private rents pushed them to begin a difficult struggle against

the high rents. Tempted by the prospect of saving money and equalizing the rents of

the neighborhood, about 1,200 families in private rented accommodation undertook the

practice of rent self-reduction. Housing campaign groups with elected representatives

were formed for each property agency involved. In November 1971, rent self-reduction

reached 75 percent of established rents, thus equalling that of social rents. Evictions

were immediately opposed with picket lines and the participation of hundreds of people,

including women and children. The Magliana neighborhood committee was born out of

this, and although it was open to extra-parliamentary militants it remained committed

to its own decision-making autonomy. As a result, it became a model to be adopted

in other neighborhoods, not so much in terms of exporting the forms of the struggle

but in terms of its constant mobilization and the attitude it maintained when dealing

with its counterparts. The initiatives by the housing campaign group stood out as

being unusually versatile. The Magliana housing campaign group gathered information

and documentation on the origin and legal status of the neighborhood, thus making

it possible to start a judicial investigation that finally led to the indictment of

140 individuals including builders and public administrators.875 At the same time, civil magistrates began to challenge eviction requests put forward

by property owners, and instead demanded evidence of (non-existent) health and safety

licences.876 Encouraged by this result, the campaign group started litigation for the redevelopment

of the neighborhood to be enacted according to bill 865. It also tried to rely on

a judicial instrument, »popular action«, for the enforcement of sanctions against

unlawful construction works (estimated at 20 billion lira), never requested by the

municipality.

The recourse to legal action in support of illegal practices was unique. In the Alessandrino

neighborhood, rent self-reduction and the struggle against evictions encouraged the

residents to denounce a DC property owner, Italo Schettini, for tax evasion. »The

working class has learned to use the bourgeoisie’s instruments« observed the paper

of the LC, which had opened premises in the area in 1970.877 Rent self-reduction, albeit to a lesser extent, also proved successful in the IACP

social accommodation in Tufello and in a number of private properties in Portonaccio,

where there was a 50 percent reduction in rent prices.878 Both cases had the support of the AO, Avanguardia Operaia (Workers’ vanguard), an organization increasingly arguing against SUNIA regarding

this issue. The latter was also engaged in rent self-reduction practices but only

for social housing and not private properties, limiting the reduction to 10 percent

of rent prices.879

Similar to the Magliana experience in terms of social involvement, versatility and

the ability to exploit the conflicts raging within local institutions, there was the

struggle in Primavalle in the north-west of the city. Like other official borgate erected during the fascist era, Primavalle still retained some of the features of

the era, including the coexistence of temporary and permanent accommodation.880 The former were small, single storey homes similar to shanty dwellings. They were

destined to be demolished but both their demolition and any work on them had been

stalled for a long time. At one point, however, the 400 families who had been living

in them were informed about a plan that would move them to a distant area, Prima Porta.

Coordinated by a Comitato di lotta per la casa Primavalle, the inhabitants of the temporary accommodation succeeded in averting the plan. Through

unrelenting campaigning and constant monitoring of the bureaucratic process the Campaign

group was able to achieve its goal: social homes were built in Primavalle to replace

the temporary accommodation in accordance with bill 167/62. These became available

in 1976 on the basis of an allocation system drawn up after »dozens of popular assemblies«.

In that year, the outer walls of the temporary homes were colored with murals inspired

by the ongoing struggle, and so a symbolic reappropriation of the borgata took place.881 A news bulletin edited by the housing campaign group wrote of a »discovery of politics«

which was paving the way to the »advancing of the oppressed against bourgeois domination«.882 Other factors can further explain the success achieved by the housing movement on

a local level. For example, the »practical goal« strategy adopted by the campaign

groups was likely to achieve more short-term results than those that opposition parties

could guarantee. Rather than a discovery of politics in more or less revolutionary

terms, therefore, it was the perspective of tangible results that marked the popularity

of these methods of struggle, as suggested by a Primavalle resident interviewed in

1973:

We believed in these kids, we struggled with them, we acted, put up posters demonstrations,

squatting, these are things one does in the struggle […] we also had arguments with

the PCI, we discussed these things, and we saw the reaction of communist comrades

in the streets, they say we got it wrong this way, our place is with them and not

here. But in 31 years since I was born in the shantytown, I’ve got nothing from them,

now for the last two years I’ve seen some hope […] practically we defeated the bosses,

we said no! You build our homes in Primavalle! 883

Neighborhood committees mobilized on various fronts which also included the environmental

issue, a topic that was increasingly gaining attention. The most radical groups approached

the question with an attitude of criticism towards the damage done by capitalism,

and for them it had to be tackled through the »right to decide how the city is to

be run« rather than through a generic demand for suitable green areas.884 Yet, it was precisely over this issue that the most successful demonstrations took

place, sometimes culminating in the occupation of the areas people wanted to be converted

into public parks.885 At Parco del Pineto in Valle Aurelia and Pratone delle Valli in Conca d’Oro, where

the dispute went on for years, people fought against the interests of one property

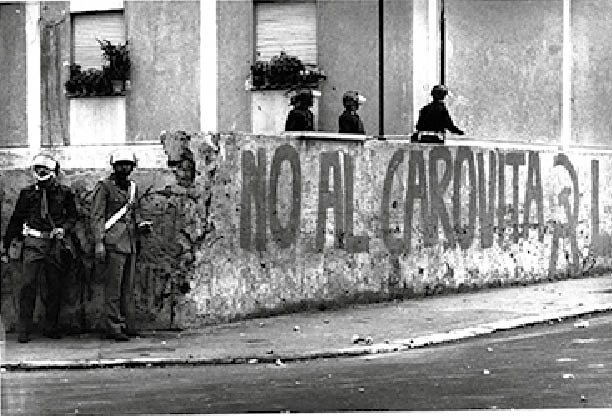

company, the Società Generale Immobiliare.886 Another front which engaged the housing campaign groups was that of a price freeze,

a practice that saw not only the proliferation of »small red markets«, where goods

purchased by small producers were sold at fair prices, but also price reductions imposed

through more radical methods. Rather than so-called expropriations, particularly popular

in this respect was shopping based on political prices, whereby shoppers paid prices

considered adequate to the value of the goods purchased. »I believe there is a difference

between taking things without paying and taking things by paying a fair price«, women

engaged in this kind of direct action declared.887

The prominence exercised by neighborhood committees, however, is also to be viewed

in relation to the changes caused by the economic crisis looming at the beginning

of the seventies. Recession, particularly serious in Italy due to alarming inflation

rates, wiped out all hopes of political reform. In the short term, it certainly helped

to give more credibility to the forms of action promoted by the housing campaign groups.

As the crisis was leading to an increase in unemployment rates and costs of living,

and the authorities were appealing for more sacrifices, the housing campaign groups

responded with self-reductions of the cost of services, insisting that disadvantaged

social sectors should react to the decrease in spending power with a »re-appropriation

of the wages on the ground«. It is important to highlight how, at this time, revolutionary

fringe groups experienced discussions and splits that undermined their internal solidity,

with consequent confusion and division on the one hand and new alliances on the other.

This marked the birth of the Autonomia movement, which in Rome established its headquarters at Via dei Volsci in the neighborhood

of San Lorenzo. It was formed of various collectives and campaign groups which aimed

to exercise, according to them, a role such as the one the Soviets had in revolutionary

Russia, whose activists were at the mercy of social and political behaviors which

revealed an exasperated subjectivism. Similar in their approach although often in

conflict with Via dei Volsci, were the militants of the OPR, Organizzazione proletaria romana (Proletarians’ Organization of Rome), based in Casal Bruciato and more inclined towards

a Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy. Both trends developed significantly in the years from

1972 to 1975, and eventually took on a prominent role in the 1977 movement.

Neighborhood committees, in the meantime, began to improve their political intervention

thanks to the adoption of the survey as a tool. Questionnaires (for example: »in your

opinion, what are the most urgent needs in the neighborhood?«)888 were distributed, information was gathered door-to-door, discussions were organized

in public places, such as cinemas, with the aim of collecting »documents and evidence

for pressing charges against the authorities«. In this way, it was possible to assess

the level of social unease and action was taken with respect to the problems raised.

This was the work undertaken, for example, by the CUI, Comitati unitari inquilini (Tenants’ United Committees) in the areas linked to Avanguardia Operaia. The CUI of Val Melaina-Tufello gained significant consensus by tackling the problems

of sewage and malfunctioning heating, with demonstrations being staged outside the

IACP premises.889 The practice of challenging state agencies and private companies in a collective

way became widespread. In Casalbertone, residents wanted private property agencies

to give official explanations for the increase in the cost of heating and other services,

and they threatened to withhold payments if their demands remained unanswered; tenants

in Garbatella and Tor Marancia, for their part, self-reduced their electricity bills

and subsequently informed the municipal electricity company about it.890

The Ministry of the Interior observed how these actions of »civil disobedience« also

interested »the social groups normally alien to similar forms of protest«, thus generating

concerns of public order and adding to the budget deficit of most service providers.891 The practice of self-reducing utility bills was fundamental to the success of the

most radical campaign groups and encouraged a broadening of the housing struggle.

The self-reduction of electricity bills began early in 1972 in Montecucco (Portuense

neighborhood) when dozens of families, influenced by local LC militants and those

from the Comitato politico Enel (Political Committee of the national energy company), one of the most important committees

in the area of Autonomia, began to pay their bills at the cost of 8 liras per kilowatt per hour instead of

43 liras, i. e. the same price granted to entrepreneurs for industrial activities.

People used to mark their electricity bills with: »We pay 8 liras like the bosses

do«. If the practice appeared to be faltering at the end of that year, it regained

momentum in Val Melaina, Tiburtino and Ostia in 1973.892 As the Rumor government decided to increase electricity rates by over 40 percent

in August 1974, bill self-reduction became a common practice adopted in about twenty

neighborhoods, with the involvement of the LC and the CUI of Avanguardia Operaia.893 The committees linked to Via dei Volsci remarked that the success of this struggle

depended on it being properly »defended«. It was therefore necessary to organize »watch

shifts to prevent power cuts from being enforced by electricity providers«.894 Interestingly, many ENEL staff assigned with the task of cutting power showed solidarity

with the struggle and refused to undertake their task.895 Tensions erupted in some instances, such as in Ostia where women in social housing

opposed not only power cuts, but also the subsequent attempt by the electricity company

to confiscate their belongings in order to make up for the loss.896

Self-reduction was also applied to phone bills as Autonomia committees recommended paying only the standing charge. Telephone service cuts enforced

in Val Melaina, the epicenter of the struggle, provoked strong reactions and protests.897 In 1975, when most households still did not have telephones, there was an increase

not only in call costs but also in line rentals and connection fees. The forecast

in the trends in the telecommunications sector by the Left (from the extremist fringes

to the PCI) was significant. They foretold a situation in which investment in more

profitable areas (electronics, TV cables, radio-telephones) would badly affect social

services and was therefore to be regarded as a measure »against the working class«

destined to be excluded from benefiting from it. This would, however, prove untrue

some time afterwards.898 Autonomia militants kept encouraging electricity bill self-reduction even after an agreement

they considered totally insufficient was reached between the government and the union

in December 1974.899 In contrast, the AO appeared more inclined to discuss the issue of phone costs with

the unions whilst still encouraging the self-reduction of bills.900 That the various groups of the movement displayed different approaches had already

become evident with the house-squatting movement, which hit a climax in the winter

of 1973–74.

The Movement of House Squatting in the Winter 1973–74 and the San Basilio Revolt

Conditions in the property market were particularly disadvantageous for tenants at

the beginning of the seventies as rents registered a sharp and sudden increase.901 Thousands of flats were built in Rome, but they often remained empty due to high

rents.902 Private property owners tended to invest in the already saturated market of mid-luxury

accommodation, whereas social housing providers continually failed to provide the

housing that was needed.903 The neighborhoods singled out as privileged places for political intervention became

the outposts of a massive house-squatting movement. It began in San Basilio on 9 November

1973 as young couples occupied 148 social homes.904 On the same day, in Magliana 220 private homes were occupied; these were sequestrated

buildings which had been empty for years after their owner, DC member Straziota, had

failed to pay the mortgage.905 The two actions, supported by the LC’s housing campaigning groups, started off a

mass movement, which this time targeted mainly private properties left unoccupied

or unfinished. On 15 January 1974, 187 apartments belonging to the Sara company were

squatted in the neighborhood of Don Bosco by the Comitato proletario per la casa, an offshoot of the OPR.906 The same campaign group was also responsible for the occupation of Apolloni Constructions

homes in Alessandrino and Enasarco homes in Casal Bruciato. On 25 January, entrepreneur

Caltagirone’s buildings in Portonaccio were occupied with the contribution of the

AO and the LC. Caltagirone’s properties were also targeted in Nuovo Salario, where

autonomous militants from the Comitato di lotta Val Melaina and militants from the AO were active proponents. These actions aimed to challenge

the political practice of the municipality covering the costs of accommodation for

people in need, a line that protected property owners, and to relaunch the practice

of the sequestration of private properties left empty. This accentuated the differences

between the revolutionary Left and the institutional one. Moreover, there was a tendency

to emphasize how the social status of those occupying homes had changed, as they were

now comprised mainly of factory and service sector workers, so as to demonstrate that

the housing problem was no longer limited to shantytown dwellers.907

The month of February witnessed a string of evictions and re-occupations, particularly

in Nuovo Salario and Portonaccio where the most serious incidents took place.908

Other occupations were in Garbatella, Laurentina, Portuense, Pineta Sacchetti, Casalotti,

Ostiense, Cassia and Colleverde.

As the squatting movement was thriving, the points of disagreement among the various

bodies involved seemed insignificant but they became obvious in the face of the opposition’s

reaction. On 11 February, builders threatened the total closure of all construction

sites if more occupations took place and the ongoing ones were not cleared out. Most

remarkably, in some cases property owners hired individuals as mercenaries to stay

in buildings in order to avert squatting. Slowly but steadily, the existence of certain

repressive operations came to light, the most controversial being the work of Ennio

Pompei, one of Andreotti’s men with a past in the neo-fascist MSI party, also chairman

of the Nuovo Regina Margherita Hospital. He had given leave to 130 hospital staff

and had recruited them as wardens at evicted homes in Nuovo Salario.909 A heated argument exploded between the many left-wing groups in relation to the possibility

of re-occupying homes guarded by private wardens, especially when the wardens were

known fascist members (as was the case in Portonaccio): the AO, for example, judged

an OPR attempt at taking action a provocation.910 The AO and the LC, however, found reasons for agreement. The LC had expressed strong

criticism towards those who encouraged divisions between squatters and construction

workers by organizing »impromptu« occupations of homes under construction, and also

towards those who used the struggle as »an occurrence of mere physical confrontation

to be pursued in all circumstances at all times«.911 The target of the criticism was Autonomia, which based the struggle for housing on an »active defence of the goal« as the only

way to establish »structures of proletarians’ power« on a local level.912 Autonomia militants, for their part, criticized the OPR and the AO’s decision to occupy churches

and basilicas symbolically in protest of evictions, describing the act as a sell-off

of the movement, a »moaners’ pressure on bourgeois power«.913

The AO and the LC were also in agreement on the key demands that empty homes be sequestered

and rent levels should be kept below 10 percent of workers’ wages. These demands were

at the heart of the movement’s participation in a demonstration for housing rights,

which was convened by the unions on 19 February 1974. Pressure exercised by the unions

forced the municipal administration to plead with the government for measures »aimed

to reduce renting prices to what can be afforded by workers’ wages«.914 Far more decisive, however, was pressure exercised by constructors: their repeated

claims induced prefect Ravalli to promise a plan for extended evictions.915 Enforced on 25 February, it was completed a month later with a total of 2,946 evictions,

many episodes of urban guerrilla activism, 563 people under investigation and 48 arrested.916 598 homes, however, remained occupied in Magliana and San Basilio.

The evictions in San Basilio that went ahead between 5 and 8 September 1974 marked

a watershed due to the way in which they unfolded violently, their impact on future

events and the suggestions raised in the revolutionary Left. Starting out as official

borgata and developed during the aftermath of the Second World War, thanks to various bouts

of public construction, San Basilio stood quite isolated from the city in the far

eastern suburbs and surrounded by countryside. It looked more like a little village

rather than an urban neighborhood, and was inhabited by a population predominantly

composed of factory workers and the lower classes, whose political preferences were

mostly for left-wing parties. Many extra-parliamentary groups, Lotta Continua in particular, had tried to establish their influence and had gained a certain number

of followers. Here the struggle for housing was most keenly felt, at least since it

had become necessary to become organized so that normal houses were built in place

of the temporary ones built during the 1940–1942 fascist era. Furthermore, owing to

serious overcrowding in the borgata, a number of the social houses built on the site during the fifties and sixties to

accommodate families in need coming from other areas of the city had been occupied

in those same years by the children and relatives of the older inhabitants. This kind

of informal practice not only consolidated a tradition but also assured the conservation

of family and community relations.

The occupation that began in November 1973 was carried out by people already living

in the neighborhoods, mostly residents in basements, parents’ homes or nearby illegal

borgate and therefore they could rely on the support of a large part of the local population.

However, during the ten months of occupation, bureaucracy had completed its trajectory

and homes had been allocated, with the usual delay, to those entitled.917 Coordinated by the PCI through a tenants committee, they pleaded even with the President

of the Republic for the »liberation« of squatted homes.918 Contrary to later declarations, therefore, the PCI had been unable to open a window

for negotiation. On the contrary, the party newspaper, l’Unità, had been discrediting the previous winter’s occupations in the strongest terms,

even suggesting that they had been organized in league with builders in a vile plot.919 Police intervened in San Basilio with massive deployments and challenged the inhabitants

just like an occupying army. During clashes between police and demonstrators on 8 September,

nineteen-year-old Fabrizio Ceruso was shot dead almost certainly by a bullet fired

from a police gun. There followed a gunfight from both sides and many policemen were

injured.920 Finally, the families who had been squatting in San Basilio moved to homes in Casal

Bruciato rented by the Enasarco provident institution and paid for by the municipality

in accordance with a regional bill.

The events of September 1974 raise points for reflection on the issue of violence

and the way it was used in the struggle for housing, a struggle whose long history

over very different phases had been characterized by a great number of episodes of

resisting eviction.921

Certainly, the recourse to organized violence had escalated in the seventies and in

this the defence of occupied homes functioned as a »laboratory« in which to experiment

with violence-orientated techniques.922 However, the particular context of Rome’s borgate should also be taken into account, as these places were a crucible of social violence

already prone to tension and public disorder. Dramatic episodes of street fighting

involving the use of Molotov bottles and firearms had been occurring in San Basilio

and other borgate in those years, for most of which investigations had ruled out any political connotation

and had instead attributed them to local »vandals«.923 These factors intrinsic to the social configuration of Rome’s borgate, therefore, appear fundamental to the unfolding of the uprisings of September 1974.

The events of San Basilio presented the housing problem in the capital in quite dramatic

terms. The government and the prefecture of Rome even came to the point of discussing

the possibility of sequestration to solve the urgent problem of homelessness, citing

the significant impact of the September 1974 uprising in their official reports.924 However, the possibility of sequestration was immediately ruled out, as had happened

a few years earlier and for very similar reasons: the lack of exceptional need and

the risk that judicial inquiries would impose expensive fines on the Treasury.925 Shortly afterwards, the municipality, pushed by the demonstrations organized by SUNIA,

approved an emergency plan for the purchase of 2,000 private properties to be allocated

to shantytown dwellers, alongside a construction project for another 2,000 homes to

be undertaken by the ISVEUR consortium of enterprises. The measure was judged insufficient

by the most intransigent fringes. The OPR Proletarians’ Committee, for example, promoted

the occupation of some of the properties the municipality was supposed to purchase,

thus fomenting a fierce political confrontation between SUNIA and the Proletarians’

Committee with a great deal of reciprocal accusations: the former were accused of

enacting political favoritism and the latter of »dividing the workers’ front«.926 In this way the number of occupied properties hit 1,814 in April 1975.927

At the start of the seventies, the prefect of Rome proposed that the governing authorities

»enact temporary legislation« permitting the IACP to purchase 3,000 houses for the

shantytown inhabitants in order to eliminate »up to 15,000 of the worst cases«. The

prefect recommended haste so as not to give the idea that they were simply reacting

to »the threat of serious public disorder,« because this would »be playing the agitators’

game,« adding that the troublemakers would, »rightly claim credit for themselves for

having ›forced‹ the Government’s hand«.928 These concerns were well founded. Effectively, any action taken towards eliminating

the slums was due to an intense social mobilization, egged on by, as the prefect defined

them, »a tireless and relentless band of agitators«. In fact, it was the housing campaign

groups and the neighborhood committees who provided a voice for the demands coming

from the suburban neighborhood inhabitants and which led to some local successes.

It was the climate of social tension created by the occupation movement of 1974 that

forced the authorities to make important emergency housing concessions.

During those years, the housing movement’s influence spread considerably. Its slogans

entered into common parlance, an illustration of which can be seen in 1971 when even

the association of builders, ANCE, specifically stated that a house was not simply

»an investment asset« but also »a social asset«—a term which had noticeable similarity

(in Italian) to the slogan used by CAB in 1970 »social service home«.929 The fierce opposition between the PCI and those of the revolutionary Left that formed

around the legitimacy of the occupations would in many ways be a precursor to the

confrontation that later erupted in the tumultuous events of 1977. However, at the

height of the housing conflict none of the movement’s proposals were achieved—specifically

that social service housing should not be subordinate to speculation; rent levels

should be equal to 10 percent of the worker’s salary; and requisitioning of the vacant

private housing. Instead, the PCI’s proposals were realized—the elimination of slums,

the creation of a new public housing program and the delimitation of the boundaries

of illegal borgate and the inclusion of these in the master plan. The implementation of these proposals

reached maturity in the second half of the seventies. In other words, as radical action

spread, it did correspond to the reformists’ final push that opened a new and last

season focused on social housing. In fact, the advent of a left-wing administration

in the summer of 1976 accelerated the implementation of the emergency plan and, more

generally, helped the housing economy recover, making social housing provision possible

in the areas of the city that were covered in bill 167.930 These conditions enabled the housing conflict to be partially resolved. Although

the occupations did not end,931 some political, social and even environmental changes were evident: the demolition

of shantytowns and the renewal of the borgate eliminated some major drivers behind the fight. Furthermore, many neighborhood committees

(and to some extent also those of Magliana and Primavalle) pledged their support to

the process of administrative decentralization that was taking place through the formation

of District Councils; in order to impose the »people’s interests«, of course, but

in some ways these interests ended up being absorbed into the dialogue with local

authorities that was beginning to take its first steps.932 All the same, this type of organization would, in later decades, inspire the citizen

committees that would have a less obvious political identity and be one step removed

from the growing desire for radical change. These citizen committees would be characterized

as being »participatory structures« that tended towards the use of protest as their

main action strategy.933

Before the seventies, occupations had been used as a form of pressure against the

authorities. At the turn of the seventies, occupations were an attempt for an immediate

solution for the needs of the homeless; however, this does not mean that at that point

the buildings targeted for occupation became the occupier’s residence. Except on some

rare occasions, the occupiers continued to be evicted by the police. It was in the

following decade that the housing needs of thousands of families were directly met

through occupations.934 These occupations were organized by social and political actors coming from the wake

of the experience gained during the seventies.935 In short, the activities of those years would continue to influence successive periods

of housing struggles. The political landscape changed and occupations became tolerated.

In fact, they became the quickest path to accessing public housing, considering the

extreme sluggishness with which applications for legitimate housing places were dealt

with despite much of the housing remaining empty. In 1991, the Regional Council approved

amnesty for housing that had been occupied before 27 July 1990.936 Some said the act was necessary in light of the accumulating defaults, others said

that this legislated in favor of abuse to the detriment of those who continued to

trust formal procedures. It was, on balance, an admission of failure by the administration

which was incapable of managing the social housing sector in accordance with their

own rules and procedures. However, the fallout from the housing fight does not appear

to be uniquely limited to the political sphere. It can also be said that it has maintained

a dynamic relationship with the city itself, influencing its physiognomy, and, for

example, determining the social and cultural image of the neighborhoods that received

the families who were awarded emergency housing as a result of the struggles. The

occupation of vacant houses and buildings continues to some extent today, and reflects

the current inadequacies in public housing policy, an area that continues to be amongst

the most contentious and difficult for the city and its residents.