The Settlement Initiatives and the 1970s in the Ruhr

Most of the workers’ settlements in the Ruhr were built during the heyday of the region’s

industrialization in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when a number

of medieval towns and villages along the old Westphalian Hellweg and the small Emscher

River transformed within a few years into large industrial cities.944 After the German unification of 1871 this part of the country experienced an unparalleled

economic boom and a direly needed influx of tens of thousands of workers. Workers’

settlements, which consisted of comparatively spacious two to four family redbrick

homes, almost identical in design, with a stable and garden for growing crops and

keeping small livestock, were built by or near the coal and steel companies. By providing

homes in an age of extremely high workforce turnover companies intended to deter their

qualified workers from changing their workplace and were able to maintain a greater

degree of social control over the private sphere of their employees.945

The coal crisis, which lasted from 1958 until 1968, fundamentally transformed the

Ruhr industries. Few of the coal mines that were sprinkled across the Ruhr survived

this period. In the early seventies, some 140,000 residential apartments belonged

to the housing companies (Wohnstätten) that had been associated with the Ruhr’s coal and steel industry since 1933. Despite

an ongoing and increasing demand for housing in the region, state authorities and

local politicians encouraged the demolition of these old buildings. In many cases,

the workers’ settlements had not been renovated or modernized for decades.946 The local authorities, companies and parts of the population perceived them as outdated,

as a symbol of urban decline, and it was hoped they would be replaced with up-to-date

and larger residential complexes. Because of the mining crisis, the North Rhine-Westphalian

government launched the Nordrhein-Westfalen Programm (1970–1975),947 which sought to re-industrialize and modernize the Ruhr region with new infrastructure,

including plans for so-called area rehabilitation. The interests of the companies

and the State went hand in hand, as the industry also saw an opportunity to valorize

underused land and replace the buildings with more profitable ones. The State government

required the city councils to prioritize the demolition of company housing estates

and to increase the density and centralization of cities through the erection of high-rise

buildings; and the local authorities sought to comply. What was often ignored by the

local authorities then was that the houses of the settlements were greener, larger

and cheaper than the average worker’s flat in the Ruhr cities. The tenants in the

workers’ settlements, in contrast, were very aware of the extremely reasonable rent

they paid:

Look at this flat. It costs a bit more than 100 deutschmarks rent per month and we

have freedom here, garden all around, shed. Behind another garden, another courtyard,

a cellar here, a cellar there and five rooms, coming and going whenever I want. Where

else do I get this? That I won’t get for 500 deutschmarks elsewhere, for five times

the rental price, and then the flat is in a high-rise building.948

Thus, some residents resisted the destruction of their neighborhoods. At the beginning

of the seventies, the first and most famous example of a campaign against demolition

was the Eisenheim initiative, which emerged under the leadership of Roland Günter

and Jörg Boström. Neither of them were originally resident of any of the settlements

or of working-class background. Both, however, acted as conservators, artists, urban

movement campaigners and university teachers.949 Eisenheim was not only the oldest workers’ settlements in the Ruhr, with parts dating

from the late eighteen-forties, it was also the first one in the Federal Republic

that was placed under heritage protection in 1972 and thus served as an example for

the following 30 to 50 campaigns all over the region.950 From 1974, protest initiatives mushroomed across the Ruhr. The initiatives gained

attention in the West German media, where they had left-wing sympathizers, as well

as the local media.951 Working groups organized public meetings with leading representatives of the initiatives

and the local churches, the council administration, the housing corporations, state-employed

conservators and academics in urban planning and social sciences, demanding a new

assessment of the historical value and the quality of life in the workers’ quarters,

and efforts to revive empty buildings.952

A comprehensive network of workers’ settlement initiatives grew across the Ruhr in

which few of the inhabitant campaigners directly participated, however. This network

was complemented by networks of broader initiatives within the individual Ruhr cities,

with foci beyond the preservation of the historic workers’ settlements. In Dortmund,

for example, a strong city-based network Arbeitskreis Dortmunder Initiativen was founded to facilitate solidarity among all urban movement initiatives.953 The settlement initiatives thus found solidarity in other urban movements and tenant

initiatives against exorbitant rents and redevelopment.

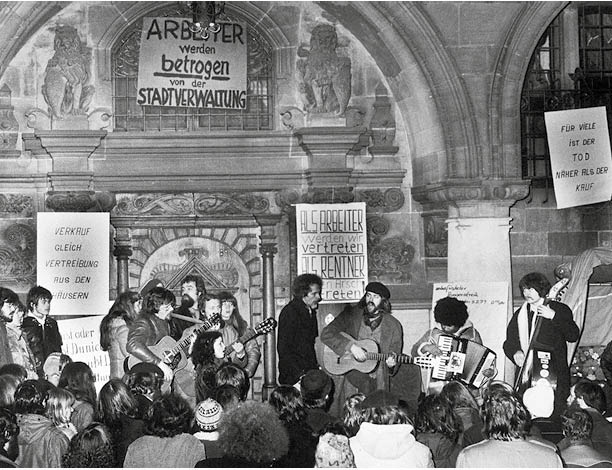

The workers’ settlement initiatives performed various »civic« forms of protest in

order to convince the housing companies, the Social Democratic Party (SPD), the strongest

political force in the Ruhr communities, and local officials of their cause. Once

a settlement was saved from demolition—often after being put under preservation order

by the state heritage authorities, and as an outcome of a long-lasting communal bargaining

and decision-making process—however, the threat to the communities persisted in the

form of privatization.954 Thus, from the mid-seventies it was not necessarily the demolition order that sparked

protests among the initiatives.955 When in 1976–77 the housing companies changed their policy from demolishing to selling

the workers’ settlements, as they recognized the potential for valorization of the

properties, few tenants were able to afford the purchase of the flats and semi-detached

houses. Lower middle-class buyers and skilled workers were among the new owners. Several

further protest groups emerged seeking to maintain their settlements as rental properties.

Politicians of the major parties, unionists and workers’ representatives of the Ruhrkohle AG956 supported the idea of selling to the workers, who would thus have the opportunity

for capital accumulation. At this point a conflict of interest emerged within the

settlements and the consensual actions for the preservation of the status quo lost

ground. At the same time, however, the protest also became more organized and protest

groups more systematically trained. Activists wrote letters to local newspapers, appealed

to the local council,957 organized tenant assemblies and street festivals, distributed pamphlets and started

petitions.

In occupying the houses the initiatives also borrowed some more radical methods of

the then emerging squatters’ movement. The Rheinpreussen initiative in Duisburg from

1975 onwards was the first initiative that squatted an empty house in the settlement,

and it was probably the only one that also went on hunger strike to pressure the city

council into buying the settlement.958 The musician Frank Baier, one of the protagonists of the Rheinpreussen initiative,

then started writing protest songs for the demonstrations.959 It is worth noting that since the early seventies Baier had been connected with radical

left-wing voices outside of the Ruhr, such as the then West Berlin-based music group

Ton Steine Scherben, and he was also involved in the antinuclear and squatters movements.960 Baier, thus, not only represented the typical working-class and regional culture

of the Ruhr, but also the left-wing protest culture in the cities of the seventies

that transcended regional and national boundaries.961

The »Right to the City«: the Emergence of an Alternative Public

Since the sixties, the image of the modern city in the industrialized West has been

contested by authors calling for social protest against the often depressing Fordist

and postwar architecture.962 While »the right to the city«, deriving from Henri Lefebvre’s Le droit à la ville from 1968, has become a catchy slogan in recent years, few nowadays bother clearly

defining what it entailed.963 Few historians have used this concept,964 and it is indeed very difficult to apply Lefebvre’s holistically revolutionary ideas—including

the end of private ownership in the city and the realization of radical urban democracy—to

historical processes. It is possible, however, to identify historical moments and

movements of the right to the city. Further, the revolutionary literature of that

time should not only be seen against the backdrop of the growing urban movement activism

around the world but also be embedded in the wider protest culture of the new social

movements that developed in Western industrialized societies post-1968.

This overlap of movements at that time is well-represented in the alternative newspapers

of the Ruhr cities; for example in Bochum (Bochumer Volksblatt, later Bochumer Stattblatt),965 Dortmund (Klüngelkerl),966 and Gelsenkirchen (Emscherbote),967 which were founded in the seventies to report on the actions of local citizen initiatives.

The local newspapers were not directly linked to the workers’ settlement initiatives

but reported critically on various forms of urban change in the Ruhr cities, redevelopment

and city planning, including public transport; they informed the readers regularly

about tenant rights, exorbitant rents, the shortage of affordable housing, forced

renovation, the demolition of historic buildings, squatted houses, and homelessness;

and they reported on the establishment of youth centers and alternative cultural activities

in the Ruhr cities. They also published articles on processes of deindustrialization,

unemployment, strikes and changes in labor relations in the region. The papers discussed

police repression, conditions in prisons and reform, right-wing extremism, women’s

rights, environmental problems, including air pollution, inner-city road planning

and bicycle infrastructure, as well as anti-nuclear protests; and they generally propagated

political transparency, self-government and more participatory urban politics. These

key sources thus demonstrate that urban movement activity in the Ruhr during the seventies

cannot be studied as completely disconnected from the new social movement activities

and the New Left of that time in the region. While other German and European cities

have been identified as strongholds of the student movement and subsequently the alternative

milieu,968 the Ruhr has rarely been associated with »1968«969 and the subsequent »normalization« of protests,970 including the protests of the women’s, environmentalist, peace, anti-nuclear and

squatters movements that spread across Western Europe. However, while urban movement

actions in the Ruhr can be studied as part of a loosely connected global urban movement

that was strongly intertwined with the New Left and new social movements, the Ruhr’s

subversive media illustrate that the local urban movements must also be seen against

the region’s particular urban transformation in the course of its deindustrialization.

The Ruhr-Volksblatt (RVB),971 a newspaper published from 1975 to 1984 to represent the Working Group of Workers’

Settlement Initiatives in the Ruhr (Arbeitskreis der Arbeitersiedlungsinitiativen im Ruhrgebiet), provides an excellent insight into the dynamics and rhetoric of the Ruhr’s workers’

settlement movement. It was published every few months, with up to five issues per

year. The newspaper was designed to provide information about and for the initiatives,

to connect the initiatives across the Ruhr, to provide solidarity with and amongst

them, and to project the local concerns to the general public. The newspaper can been

seen as part of the conceptualization of a proletarian counter-public sphere in the

seventies, partly driven by left-wing intellectuals seeking solidarity with workers.972

In its first year, 1975, the Ruhr-Volksblatt listed contact details of twenty initiatives across the Ruhr.973 In the following year, Jörg Boström and Roland Günter, who were instrumental in the

Ruhr-Volksblatt, already listed 33 initiatives.974 In 1977, two years after its launch, virtually all initiatives worked to some extent

with the Ruhr-Volksblatt, although the readership of the paper was very limited among the inhabitants of the

workers’ settlements themselves. In 1978–79 the distribution of the Ruhr-Volksblatt peaked with more than 1,400 issues, despite the number of initiatives already in

decline.

The working-class tone of the protest and the local dialect of the Ruhr were endorsed

in all issues. The topics of the paper were relatively diverse, though centering on

protest. Readers were informed about the situation in the settlements and the progress

of the initiatives, and were warned of further demolition plans. The increase of rent

and privatization was repetitively discussed as well as the social and psychological

problems caused by high-rise buildings.975 While broader left-wing ideology is clearly present, conforming with the democratic

ideal of the New Left, everyday situations typical for the Ruhr, such as breeding

rabbits and carrier pigeons, also formed important topics for the paper.

A Conceptual Exploration of the Workers’ Settlement Movement

The »elective affinities« between social categories, ideologies and identities (i. e.,

social representations of identity)976 can help us better understand the urban movements within their particular context

and, thus, understand the locally variant articulations of the right to the city.

The categories correlated here are: social class, political ideology, place identity,

historical culture and aesthetic judgement. These explorative parameters shed light

on the agency of the elites within the movements and their relationship with the new

social movement ideology of the 1970s.

Social Class: Sebastian Haffner wrote in 1974 that the term Bürgerinitiative was unknown ten years before, although in principle such initiatives had existed for

a long time. 977 At the time of his writing, however, this form of protest—the local action group

or citizen initiative—was experiencing its peak in West Germany. Looking at the Republic

as a whole, workers were in a small minority among the citizen initiatives of the

1970s. The Ruhr, with its approximately 30 to 50 so-called »workers’ initiatives«

was special in that sense.978 Even though the workers’ settlements had been »discovered« by the Bildungsbürgertum (educated bourgeoisie), the participants of the initiatives were almost entirely

working-class. Bürger in German means »citizen«, though the term has a strong middle-class connotation.

The term Arbeiterinitiative (workers’ initiative), as predominantly used by the protest groups for the preservation

of the company towns and miners’ settlements in the Ruhr, was a self-given name to

distinguish themselves from the more bourgeois campaigners outside of the Ruhr and

to emphasize that their protest was led by workers to protect a particularly working-class

milieu. However, not all of them did so: in Gelsenkirchen, for example, the activists

who protested for the preservation of the Zoo settlement around the former coal mine

Graf Bismarck called themselves Bürgerinitiative Zooviertel.979

The number of working-class citizens in the initiatives, nevertheless, tells us little

about the ideological and organizational effects middle-class intellectuals had on

the movement. The initiatives were strongly shaped by individual »advisors« (Berater), described by Thomas Rommelspacher as »politically engaged intellectuals, who often

had highly qualified jobs.« These middle-class activists from outside who sympathized

with the workers in the settlements often were professionals in public service and

included »architects, city planners, sociologists, social workers, art historians

as well as students of various disciplines« who had often felt attracted by the, for

them, exotic working-class culture in the settlements and sought to overcome class

boundaries.980 This is interesting, as the village-like life in the settlements in many ways represented

the petty-bourgeois lifestyle aspiration of the working classes.981 Nevertheless, despite the relatively high living standards and the many skilled workers

who had lived in the settlements, the settlements were not a prestigious place to

live in the seventies and were still perceived as places for the lower rungs of the

Ruhr society. When the initiatives emerged, many younger workers had already left

the settlements, whereas older generations—familiar with the traditional working-class

milieu of the Ruhr—stayed behind. While younger generations began aspiring to a more

individualized, competitive middle-class lifestyle, the older generations saw in the

predicted urban renewal a more comprehensive threat to their traditional working-class

lifestyle.982

Working-class identity, as the Ruhr-Volksblatt illustrates, mattered greatly in the representation of the protest. The intellectual

editors of the paper sought to downplay their role in the publication and emphasized

the linkages between working-class identity, the local dialect and the regional identity

of the Ruhr,983 which did not necessarily match the issue-focused interests of the workers who simply

wished to maintain their homes. Half of the initiatives had sympathizers from outside

of the settlements. The Flöz Dickebank initiative, for example, had four advisors,

more than the norm for each initiative.984 In some cases, the advisors acted as founders of the initiatives. They instructed

the inhabitants in public relations and provided legal advice. They assisted the settlement

inhabitants in emancipating themselves politically through protest and participation;

and, due to this middle-class support, the authorities and companies took the working-class

protesters more seriously. When Eisenheim came under heritage protection, the officials

recognized that the working-class community of the settlement and its social structure

was worth being protected.985 The impact of Roland Günter, who had previous experience in more middle-class initiatives

outside of the Ruhr and sought to transport the participatory ideology and organizational

experiences to the working-class community of Eisenheim, was remarkable.986 The son of a wealthy industrialist who had worked as a state-employed conservationist

and professor of art and cultural theory at Bielefeld University of Applied Science,

Günter, was immensely influential across at least three areas: firstly, he was instrumental

in the above-mentioned early Eisenheim campaign, which served as a positive example

for following initiatives; secondly, he was successful in networking with other campaigns;

and thirdly, he managed to promote the memory of the Eisenheim campaign and his own

agency therein.987 Günter has remained the most famous figure not only of this protest movement, but

is also commemorated in the Ruhr’s history as an initiator of the industrial heritage

movement.988

The strong role of the advisors in this struggle, volunteering to represent working-class

interests, is also partly due to the absence of the traditional organizations of worker

representation in the Ruhr which, after the Second World War, were, foremost, the

governing SPD as well as the IGBE miners’ union (Industriegewerkschaft Bergbau und Energie). The union, which owned large housing estates across the country, could not be mobilized

to resist the destruction and privatization of the traditional neighborhoods. Instead

the initiatives came to openly attack IGBE when, in 1977, the union raised the rent

of 15,000 tenants throughout the Ruhr.989 The Neue Heimat, the enormous housing enterprise that had been founded by the Nazis and since 1952

had belonged to the Confederation of German Trade Unions (DGB) in the seventies was

strongly supportive of large-scale urban renewal and criticized by urban movement

activists and their sympathizers—a key agent in producing »inhospitable« cities in

West Germany.990 Likewise, in the seventies the German tenants association (Deutscher Mieterbund) lost public trust after supporting the rent increase pushed by the housing corporations

(Wohnstätten).991 The traditional labor representatives, thus, were suspiciously seen as allies of

the social democratic city councils and the industry in endorsing destructive city

planning.992

Political Ideology: Membership in political parties was usually around ten percent

in the workers’ settlements, while trade union membership was significantly higher.993 The movement leaders certainly evoked a certain working-class identity and leftist

ideology in their rhetoric. For example, a poster of the Flöz Dickebank initiative

stated: »We workers defend our living quarter against real estate speculation and

city destroyers« (Wir Arbeiter verteidigen unser Wohnviertel gegen Bauspekulanten und Stadtzerstörer).994 The network sympathizers with the workers’ settlement initiatives also supported

the growing squatters movement in the Ruhr towards the eighties and expressed concern

about unjust city planning, empty houses, and exorbitant rents more generally.995 Surveys showed, however, that most inhabitants and campaigners had a rather »Not

In My Backyard« attitude; they did not care much about ideological ideals and demonstrated

little solidarity with other initiatives than in their own neighborhood. Their protest

was, foremost, about preserving affordable rents and living quality in their own quarter.996

The SPD youth organization (Jusos) occasionally did support—and sometimes initiated protest campaigns for the protection

of workers’ settlements,997 but the initiatives emerged predominantly as self-help organizations for workers

outside of established political institutions. As highlighted by Lutz Niethammer in

his groundbreaking oral history of the experience of fascism in the region from 1983,

regional identity and political ideology, i. e., Social Democracy, enjoyed a special

relationship in the Ruhr region during the second half of the twentieth century. He

found that »the political behavior of this workers’ and employees’ region« had been

different from the rest of the Federal Republic. »The social-democratization of the

Ruhr,« according to Niethammer, took place after the Second World War—despite most

of the Federal Republic then electing Chancellor Adenauer with an absolute majority—even

though Social Democracy during the Weimar Republic had been »surprisingly weak« in

the Ruhr as one of the largest industrial regions in Europe, lagging in terms of votes

behind the Catholic center party and the Communists.998

While the Social Democratic ideology would play an important role in Keynesian programs

to assist the deindustrialization of the Ruhr and major industrial heritage projects

over the following decades, the fact that the SPD favored large-scale urban renewal

in the seventies made it an opponent of the workers’ settlement initiatives.999 It was rather the emergence of a new political culture, i. e., the extra-parliamentary

protest culture of the New Left and new social movements, which appealed to principles

of socialism and radical democracy, together with the new »tenant consciousness«1000 that simultaneously became apparent in the Ruhr and provided the settlement movement

with legitimacy. The advisors’ political ideology was not cohesive, but it was shaped

by the practice of the new social movements.1001

Interestingly, a number of local priests also supported the demands of the movement—social

security, belonging and participation—with arguments from Christian theology. The

Dortmund Association of Lutheran Parishes, for example, strongly encouraged citizens

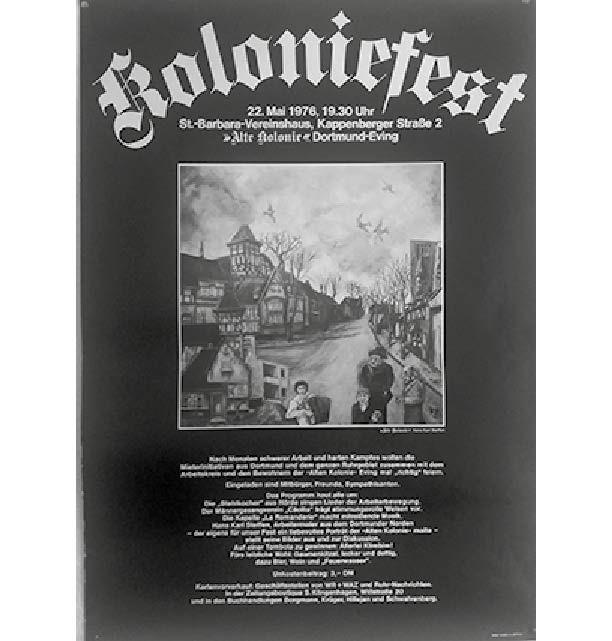

who were not directly affected to get organized and protest.1002 Some successful initiatives, such as the one for the preservation of the Alte Kolonie

Eving in Dortmund, were primarily led by clerics.1003 Church membership in the workers’ settlements was high and the clerics found in the

preservation of the quarters a theological justification: the New Jerusalem as a metaphor

for any city, which would require social action for social justice and the protection

of the community from anonymity. The priests linked the provision of leisure time,

place identity and worker participation in the settlements to biblical matters. The

major concern among the clerics, akin to the one among the inhabitants, was the workers’

overall quality of life that was generally seen as higher than in the new settlements

of the postwar period. The threat of demolition or privatization of the settlements

was presented as a symptom of more general problems in society: the housing corporations’

profit motif was threatening »Heimat« and »social justice«.1004 Apart from their spiritual legitimation the clerical arguments in Dortmund were thus

hardly different from leftist arguments across the Ruhr.

Place Identity: The older inhabitants of the workers’ settlements in particular had

developed a strong identification with their neighborhood where »everyone knows everyone«,1005 and this attachment supported the mobilization of the initiatives. The emphasis on

neighborhood solidarity amongst the working-class inhabitants was very pronounced

in all campaigns for the conservation and against the privatization of the settlements.

In a number of settlements the Social Democratic housing co-operation model was implemented

to prevent excessive privatization, maintain a relatively high degree of participation

and preserve the village-like community structure in the neighborhoods.1006 This communal image of the former company towns stood in opposition to the anonymous

living in high-rise apartment blocks. One could argue that this image, to some extent,

conflicts with the emphasis on the »urban« in urban movements. The initiatives in

the Ruhr, with its numerous intermediate spaces between the city quarters and relatively

low population density, therefore, rather constituted a suburban type of movement

action at the periphery that was not concerned with marginalization from the metropolitan

center or what usually is associated with movements for the »right to the city«.1007 It was a fight for a particular kind of right to the city, i. e., the right to preserve

the autonomy of an urban structure that had grown over generations.

The Ruhr-Volksblatt romantically presented the workers’ settlements of the region as a kind of idyll

that was typical for the Ruhr.1008 Beyond the localized identification with their own quarter, as mentioned above, the

movement leaders and sympathizers thus sought to use and reproduce representations

of regional identity in the Ruhr. The paper deployed the local rhetoric and dialect,

and represented typical items of the Ruhr culture. For example, it reported very favorably

on the typical working-class leisure activities, such as pigeon keeping, in the region.1009 This illustrates how the movement elite mobilized particular images of the Ruhr and

its working classes to represent a culturally cohesive image of the region. This was

also reflected in Roland Günter’s invitation of the above-mentioned activist and musician,

Frank Baier from Rheinpreussen, to visit Eisenheim and record the workers’ songs commemorating

the Ruhr uprising of March 1920 that some of the elderly people in his neighborhood

had sung.1010

Historical Culture: »Urban movements«, to follow Hans Pruijt’s succinct definition,

»are social movements through which citizens attempt to achieve some control over

their urban environment«.1011 The example of the workers’ initiatives in the Ruhr suggests that the quest for control

becomes especially pronounced when the urban environment is perceived as undergoing

deep-cutting transformations that affect the social structure and its meaning at the

local level. Since the urban environment is more encompassing than material or built

environment and often is symbolically charged with narratives about the past, urban

movements have also played a role in urban memory politics and the historical culture

that is aesthetically shaped by architecture, monuments and memorials, heritage sites

and the naming of urban places.

In the settlements—social scientist Janne Günter, Roland Günter’s wife, argued in

her study on the workers’ life in Eisenheim—the inhabitants had developed a sense

of historical identity, with collective experiences over generations.1012 Rommelspacher also found that one of the particularities of the settlement movement

in the Ruhr was that the activists here could draw on a rich repertoire of working-class

cultural experiences and patterns of behavior such as solidarity. The older generations,

who were overrepresented in the settlements by the seventies, had experienced or participated

in the labor movement of the twenties and thirties and lived the everyday working-class

culture of the previous decades.1013 Admittedly, at the time of the settlement initiatives, the workers could still draw

on a particular historical repertoire, filled with the shared memory of work, for

which there was hardly need any longer; but to what extent this memory was »collective«

and constituted »identity« remains doubtful.1014 Perhaps it was exactly this transitory period, from industrialism towards post-industrialism

and from the persisting authoritarianism of the postwar period towards a more anti-authoritarian

political culture in the seventies that assisted the formation of a more cohesive

historical culture in the Ruhr; after all, the production of lieux de mémoire (Pierre Nora) and the invention of tradition (Eric J. Hobsbawm) tends to flourish

in times of transition, when traditional communities are declining to form new imagined

communities (Benedict Anderson).

The conservationist struggles of that time indicate that the decline of the coal and

steel industries had a transformative effect not only on the urban landscape and people

of the Ruhr, but also on their historical culture.1015 As part of their protest against destructive city planning, the alternative press

in the Ruhr also began to take the industrial past of the region seriously and reported,

for example, on the (threat of) demolition of important industrial heritage sites

such as the Zeche Hannover mining complex and the associated miners’ settlement.1016 The industrial heritage movement thus overlapped with the urban movement of the workers’

initiatives in the settlements, which would ultimately help prolong the post-industrial

identity of the Ruhr as a region.1017 Thus, even though protests for the preservation of the Ruhr settlements were not

primarily driven by the intention of practically articulating a distinct historical

consciousness,1018 the settlement initiatives can be construed as fundamental to, and one of the most

crucial stimuli of, the later success story of industrial heritage across the Ruhr.

In the Ruhr’s seventies there was an affinity between industrial heritage initiatives

and urban movement initiatives from below, including the then widespread youth center

movement.1019 The establishment of the sociocultural center in Essen as part of the campaign to

prevent the demolition of the Zeche Carl coal mining complex and the destructive »area rehabilitation« in the Altenessen neighborhood

well elucidate these colorful movement relations.1020

Beyond informing the place identity of the Ruhr, the preservation of workers’ settlements

stood for a historical culture that also involved the memory of important questions

in urban planning that had emerged with the industrial age. Urban historian Franziska

Bollerey, for example, in the 1970s sought to raise historical awareness of the architectural

efforts taken since the nineteenth century to improve the living and housing conditions

of workers in the Ruhr cities. She also sought to historicize capitalism and divestment

in the Ruhr since the coal crisis of the late fifties which had triggered a process

of valorization that endangered the traditional life of the workers and the industrial

heritage of the region.1021 In this decade, a new affinity between heritage protection and left-wing thinking

transpired. The then emerging industrial heritage movement in the Ruhr contested established

discourses of heritage.1022

Aesthetic Judgment: The Ruhr’s particular urban design and historical identity are

still fundamentally based on the remains of its coal and steel industry that boomed

for less than a century. While this industry has faded, its built heritage has gained

in importance, starting with grassroots initiatives in the late sixties for the protection

of what in Germany came to be called Industriekultur.1023 In 1969 the machine hall of the coal mine Zeche Zollern in Dortmund was recognized

and protected as an industrial monument. The petition to the North Rhine-Westphalian

prime minister to save this building was predominantly initiated by artists, architects,

art historians and historians, marking the origin of the industrial heritage movement

in the Ruhr. The subsequent aesthetic interest from artists and art historians in

industrial heritage continued to be an essential element in the transformation of

the cultural landscape of the region. The heritage protection of Eisenheim can be

seen as the second major achievement of the Ruhr’s industrial movement. Roland Günter,

who then worked for the Rhenish Department of Heritage Conservation, saw the architectural

design of the settlement as worth being protected.1024 Thus, in 1974, the state conservator of North Rhine-Westphalia listed the Duisburg-Neumühl

workers’ settlements as protected heritage because he saw the buildings as »a typical

example of the garden city movement.«1025 This movement of the early nineteen hundreds in Germany had aimed at protecting workers’

communities from real estate speculation, following the belief in the workers’ right

to live in a healthy as well as beautiful built environment within industrial cities.

The initiatives of the seventies sought to remind the public of the value of this

garden city model that their settlements had followed; and it was exactly this affordable

and suburban living quality with green spaces that also appealed to the working-class

inhabitants.1026

The aesthetics of postwar reconstruction became increasingly challenged when in 1975

President Walter Scheel appealed at the Deutsche Städtetag to the city councils to ease the demolition of pre-war buildings. This historical

awareness went hand in hand with a growing realization that the postwar image of the

modern city had been »inhumane« and should not have followed primarily capital interests.1027 Towards the late seventies, the ongoing »modernization« and attempts to improve the

negative image of the Ruhr cities by supposedly »progressive« city planning was seen

with increasing suspicion.1028 In 1979, for example, the Bochum city council recognized that »since 1945 twice as

many historical buildings have been destroyed than during the Second World War« in

the Federal Republic. Nevertheless, the alternative press still criticized the council

for favoring profit-oriented redevelopment over the protection of art nouveau facades.1029 Similarly, the beauty of the old workers’ settlements remained subject to dispute:

for some they were just »eyesores« in the city.1030