Turtle Was Gone a Long Time Volume One, Crossing the Kedron

Introduction

Till this very day, to take hold of the first volume of Turtle Was Gone a Long Time in my hands sends a shiver of lightning up my spine. Its enigmatic title and subtitle, and the accompanying hieroglyphs immediately induce stirrings in the esoteric quarters of the mind. Yet their meaning is esoteric only to the extent that it resists instantaneous apprehension. Not one to obfuscate, Moriarty’s texts are most intelligible, but since he frequently references material that could be considered extraterritorial or exotic they refuse to be hurriedly consumed or appropriated. Turtle Was Gone a Long Time, the overarching main title of this three-volume work, is taken from a story about the origins of the Earth, as told by the Maidu, a Californian tribe of Native North Americans. Known as an earth-diver myth, it tells of how a turtle named A’noshma, dived to the floor of the world’s primal waters in order to retrieve some small portion of earth from which dry land could be made. This type of earth-diver myth represents one of humanity’s pre-eminent allegorical cosmogonies, and variants of it are to be found across the world, in Asia, Europe and America.

While in the Maidu story of origins it is a turtle that acts as the diver, in other versions of the myth the diver has been a duck, otter, frog, badger, muskrat, beaver, hell-diver, crawfish and mink, among other kinds of animals. Moriarty’s interest in the Maidu myth is as much cultural as it is cosmogonical, and once again it is essentially tied to Hölderlin’s question: ‘What are poets for in a destitute time?’ However, in Turtle Was Gone a Long Time there is a notable shift in emphasis towards Heidegger’s response to this question found early on in his essay ‘What Are Poets For?’. Heidegger writes: ‘In the age of the world’s night, the abyss of the world must be experienced and endured. But for this it is necessary that there be those who reach into the abyss.’ According to Heidegger, the German word Abgrund (‘abyss’) originally meant ‘soil and ground toward which, because it is undermost, a thing tends downwards’.1 The Ab- signifies the complete loss or absence of such ground. This lack of ground leads Moriarty to believe with Hölderlin and Heidegger that this is a destitute time and place, a place of cultural and natural destitution.

For Moriarty, A’noshma signifies a mythic figure who not only experienced and endured the Abyss but also managed to re-emerge with a little bit of soil or earth under his nails. Moriarty imagines this little bit of soil to contain ‘universal potencies’ that could once again ground humanity. On the back of A’noshma’s great deed Moriarty asks: ‘Who will be A’noshma to a new culture?’2 Who, having jumped ship will venture to the floor of the Abyss and come back with the necessary insights and principles that will give rise to a new way of seeing and being in the world? Pertinent as these questions are, it is also important to acknowledge Moriarty’s contention that it is not only the Abyss that needs to be experienced and suffered but the Canyon too. The Grand or Karmic Canyon, a perpetually recurring metaphor in Moriarty’s writings, refers in part to humanity’s archaic drives and primeval inheritance. Claiming avoidance of this inheritance and these drives signals a detour around who and what humanity is, Moriarty maintains that the Canyon must be endured, for if it is not our archaic drives will be sure to be lying ahead of us waiting to trip us up.3

In demonstrating how it is possible to sublimate humanity’s primeval inheritance Moriarty turns to Christ, who having crossed the Kedron into Gethsemane stands out as an exemplar of Divine assisted integration. According to Moriarty’s reading, St John’s terse description of Christ crossing the Kedron (a stream on the outskirts of Jerusalem), in chapter 18 verse 1 of the Gospel: ‘… he went forth with his disciples over the brook Cedron, where was a garden, into which he entered, and his disciples’, is charged with meaning, as it charts a monumental event in the evolutionary development of humanity and the Earth. For Moriarty, Christ’s crossing of the Kedron into Gethsemane relates to his metaphorical descent to the floor of the Grand/Karmic Canyon. Moreover, this crossing reveals how humanity through openness to the Divine can safely inhabit all that it phylogenetically is. In Gethsemane Christ said to Peter, ‘Put up thy sword into the sheath …’. Moriarty declares that at that particular moment Peter was not only an apostle but every dragon-slayer who ever attempted to ‘lobotomize’ or violently sanitize the psyche and the Earth. Hence, in light of what happened in Gethsemane, Moriarty finds it possible to think of Yahweh not as a slayer of Leviathan but of Yahweh reclining on the coils of Leviathan. He states: ‘Is it possible that as Hindus think of Vishnuanantasayin so we can think of Yahwehleviathasayin.’ This leads him to assert that Beast and Abyss are not as ‘incorrigibly hostile’ as might be first thought.4

Moriarty’s interpretation of Christ’s crossing of the Kedron reveals a multitude of layers to this seminal event. He claims an exodus of many interwoven strands enacted itself in Christ when he crossed the Kedron. As was just touched upon, one of its strands entails a transformation of the archetypal hero from dragon-slayer to Dracoshaya, and another strand involves an exodus from a Hebrew to Hindu sense of beginnings, whereby in the beginning was the recumbent Dreamer. However, in yet a further strand, crossing the Kedron stands for an exodus from a yu-wei to a wu-wei way of being in the world.5

Undergoing these transitions in the fullness of their implications is at times frightful, terrifying and overwhelming, and so protection is desperately needed. This to some degree explains the hieroglyphs found at the base of the front covers, and at the centre of the title pages of each of the three volumes of Turtle Was Gone a Long Time. ‘Coming forth by day’ (Pert em hru), the generally accepted translation of the hieroglyphs illustrated below are enlisted by Moriarty for guidance. For Moriarty, the Egyptian hieroglyphs

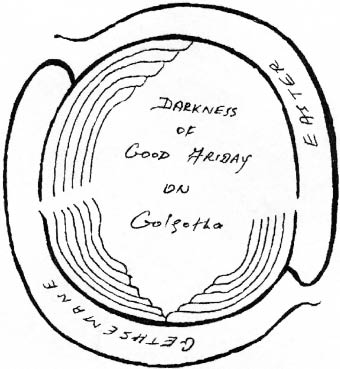

can help direct and secure humanity’s safe passage in its journey to new ground. They can aid humanity to come forth by day because Pert em hru is what the ancient Egyptians ‘called their pyramid texts, their coffin texts, that’s what they called the collections of spells and hymns and prayers in which they buried their dead’. Envisaging the possibility of a culture drawing characteristic life from the three small sounds of Pert em hru, Moriarty envisions how these five hieroglyphs, or hierogenes as he at one stage calls them, could provide a culture with direction, helping it to come forth by day.6 Besides the protection and direction of the hieroglyphs Moriarty also intersperses Crossing the Kedron with eighteen mandalas that act as garbha mandalas or womb mandalas.

The word mandala is derived from Sanskrit and loosely translates into English as ‘circle’. Of import both microcosmically and macrocosmically, the mandala is endowed with a wealth of significance. The mandala has inspired a host of varied interpretations, however, it appears no amount of explanation can exhaust its fecundity. A transcultural phenomenon, the mandala is to be found in the East, manifesting itself most splendidly in Tibetan Buddhism; it is also evident in ancient Egypt; Carl Jung in The Secret of the Golden Flower makes reference to an image of Horus and his four sons;7 in Medieval Christianity the mandala appears in the works of Hildegard von Bingen, and later on it emerges in Jacob Boehme’s writings; and it is also evident in the sand paintings of the Pueblo and Navaho Indians. Interestingly, Jung observes how some of his female patients would dance in the form of a mandala rather than draw it. He further notes how the mandala symbol is not only a means of expression but also works an effect upon its maker. Jung claims that very ancient magical effects dwell concealed within the mandala for it derives originally from the ‘enclosing circle’ or the ‘charmed circle’, the magic of which is still found in numerous folk customs: ‘The image has the obvious purpose of drawing a sulcus primigenius, a magical furrow, around the centre, the templum or temenos (sacred precinct), of the innermost personality, in order to prevent “flowing out” or to guard by apotropaeic means against deflections through external influences.’8

For Moriarty, the garbha mandalas in Crossing the Kedron are ‘figurations of the mystical journey’, which in imitation of Christ is experienced as the Triduum Sacrum. Moreover, he considers them a figurative response to the question Nicodemus puts to Christ:

There was a man of the Pharisees named Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews: The same came to Jesus by night and said unto him, Rabbi, we know that thou art a teacher come from God, for no man can do these miracles that thou doest, except God be with him. Jesus answered and said unto him, Verily, verily I say unto thee, except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God. Nicodemus saith unto him, How can a man be born when he is old? Can he enter the second time into his mother’s womb, and be born? (John 3: 1–4)9

Yes, is the answer, and according to Moriarty this is allegorically represented in the garbha mandala. These mandalas, he alleges, lead us Gethsemane deep into our own and the world’s karma. Its vulva or trail opened, Moriarty acknowledges the importance of prayer for God’s good-shepherding upon entry.10 Notably, the first volume of Turtle concludes with four mandalas emerging as the groundplan for a Tenebrae Temple, or, what ancient Egyptians might think of as Tai-wer, the first land or mound to surface out of the primordial waters. The groundplan for a Tenebrae Temple will become a central preoccupation of the third volume of Turtle.

Crossing the Kedron is itself divided into three parts, Part One: ‘Engwura Now’; Part Two: ‘Tenebrae Now’; and Part Three: ‘Tep-Zepi Now and Tai-Wer’, all of which are preceded by an important ‘Overture’. ‘Engwura Now’ consists of forty poems followed by prose commentaries. Submitting oneself to these poems and commentaries allows the reader to awaken and activate the more recalcitrant and withdrawn depths of the psyche as they seem to speak subliminally to the greater silent Self.

This, however, necessitates a tremendously difficult journey. Engwura or what Baldwin G. Spencer calls ‘the fire ceremony’ in The Native Tribes of Central Australia, relates to the final initiatory rite a male adolescent Australian Aborigine undergoes, when separated from his mother he is inducted into manhood. Illpongwurra is the name given to those who are in the process of passing through the engwura and Urliara is the name given to those who are fully initiated.11 In Moriarty’s case the engwura takes on a different meaning. No gender bias at work, his sense of engwura involves disengagement from ‘movement local’ in favour of the pursuit of ‘movement essential’. Movement local refers to movement from one locale to another, for example: taking a flight from London and arriving in New York. Alternatively movement local can pertain to upward mobility, for example: from being the clerk in a bank one becomes the bank manager. On the other hand, Moriarty explains how movement essential involves a transformative movement, that is, movement from one state of being to another. Movement essential thus entails movement ‘from being deluded to being enlightened’ as a Buddhist would understand it, or movement ‘from being a sinner to being a saint’ as a Christian would understand it.12 ‘Paradise Lost’, ‘Sir Orfeo and Lady Eurydice’, ‘Opposites’, ‘In Buddha’s Footsteps’, ‘Coming Forth by Day’, and ‘Mona Melencolia Europa’ are the six pieces chosen for the Reader. These pieces ‘so inwardly various’ rebuke synopsis but they offer a partial glimpse into Moriarty’s bold attempt to enact a journey from Paradise Lost to the gates of Paradise.

‘Tenebrae Now’ is made up of six stories or parables, which in honour of Christ are taken from ordinary, everyday life in the west of Ireland. Allegorically, the six stories correspond to the six days of humanity’s involution or return to Divine Ground. They act as a counterpart to the six days of evolution or emergence from Divine Ground. Collectively, Moriarty thinks of them as Ireland’s first Upanishad. As an Upanishad the stories seek to ‘sensuously enact a journey beyond the senses’ and thinkingly they seek to ‘enact a journey beyond thought’.13 The ‘Fifth’ and ‘Sixth’ stories are to be found here. In the ‘Fifth Story’ Moriarty finds himself walking home from a ‘hishtoric booze’ with Martin Halloran. Through Martin’s persistent questioning as to where exactly they are and through a rehearsal of the Narada parable, Moriarty is led into a state of disillusionment.

The ‘Sixth Story’ revolves around the fictional character of Big Mike. Big Mike is someone who has already been through the Job, Jonah and Narada initiations and having spent years at sea he now returns to his native island. Driven on ‘by a kind of divine compulsion’, Moriarty sees Big Mike as someone who ‘must become a new and wholly unprecedented archetype among his people’. As an archetype of humanity’s final transition or return to Divine Ground, Big Mike allows this adventure to enact itself symbolically and become visible in him.14

Moriarty brings Crossing the Kedron to a close with Part Three: ‘Tep-Zepi Now and Tai-Wer’. By doing so he is returning to Tep-zepi, the first time, and Tai-wer, the first land, that the ancient Egyptians speak of. Returning to the first time and first land, Moriarty seeks to unshackle possibilities for human flourishing that lie latent within our cultural and cosmic beginnings. The ‘Now’ indicates that these possibilities are ever present and it is up to us to realize them.

NOTES

1. Heidegger, ‘What Are Poets For’ in Poetry, Language, Thought, p. 90.

2. Moriarty, What the Curlew Said, p. 176.

3. Ibid., p. 288.

4. Moriarty, Turtle I, p. 32.

5. Moriarty, Turtle II, pp. 59–60.

6. Cf. Moriarty, Turtle II, pp. 152–3 and Moriarty, Turtle I, p. xxii.

7. Richard Wilhelm and C.G. Jung, The Secret of the Golden Flower, trans. Cary F. Baynes (London: Routledge, 1999), p. 100. Jung further states: ‘For the most part, the mandala form is that of a flower, cross, or wheel, with a distinct tendency towards the quadripartite structure. (One is reminded of the tetraktys, the fundamental number in the Pythagorean system.)’

8. Ibid., pp. 99–102; Moriarty, Turtle I, p. 232.

9. Moriarty, Turtle I, p. 232.

10. Ibid., p. 233.

11. Baldwin G. Spencer, The Native Tribes of Central Australia (London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd, 1899), p. 269.

12. Moriarty, Turtle I, p. ix. Moriarty derives this distinction from Francis Bacon’s The Advancement of Learning (1605). Bacon distinguishes between ‘advancement local’ and ‘advancement essential’.

13. Moriarty, Nostos, p. 649.

14. Ibid., p. 650.

OVERTURE

Would you open a way for us into this book? Would you give us a sense of what we are likely to find in it?

Any simple description of a book so inwardly various as this one is will, more than likely, give a mistaken impression, but, given the title of the first piece, it mightn’t be altogether amiss to suggest that it enacts a journey from Paradise Lost to Paradise Regained, or less impiously perhaps, to the gates of Paradise. Not a small claim I know. So, pulling back from such great expectations, let me put it this way: setting foot on the moon, Neil Armstrong said, it is a small step for me but a giant step for humanity. It is my belief that, yes, it was a small step for Neil and, however glamorous in appearance, a quite insignificant step for humanity. Let me say why I think this to be so. In his book The Advancement of Learning (1605), Francis Bacon distinguishes between advancement local and advancement essential. Allow me for my purposes to call them movement local and movement essential. Movement local is movement from one to another place. I leave London, say, and I arrive in Oxford and, other than in external circumstances, no significant change has occurred. Reckoned to be movement local also would be the movement we nowadays refer to as upward mobility, movement let’s say from being a deckhand on a small trawler to being Lord High Admiral of the nation’s fleet. As Bacon has it:

For as those which are sick, and find no remedy, do tumble up and down and change place, as if by a remove local they could attain a remove internal; so it is with men in ambition, when failing of the mean to exalt their nature, they are in a perpetual estuation to exalt their place.

Movement essential, as its name suggests, is movement from one to another state of being. It is transformative movement, movement from being a caterpillar to being a butterfly, movement, as Buddhists would understand it, from being deluded to being enlightened; movement, as Christians understand it, from being a sinner to being a saint.

In the modern world, almost universally now, we give ourselves to movement local. Ours is a movement-local culture. But, even though it carries us supersonically from London to New York, Concorde isn’t a cocoon. The person who climbs up into it in London is in everything except address the same person who climbs down from it in New York.

Upwardly mobile himself, Macbeth spoke the epitaph of this way of life: it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury signifying nothing.

Listen to Lao Tze talking about the Taoist sage:

Without leaving his door

He knows everything under heaven,

Without looking out of his window

He knows all the ways of heaven.

For the farther one travels (from the Tao)

The less one knows.

Therefore the Sage arrives without going,

Sees all without looking,

Does nothing, yet achieves everything.

And again let’s listen:

The neighbouring settlements may be so close that one can hear the cocks crow and the dogs bark, but the people may grow old and die without going back and forth.

I am reminded of the monk who asked: what historical epoch do people nowadays say they live in? Outside these monastery walls, I mean, what epoch do they say they live in?

I’ll tell you a story:

In Africa, two or more centuries ago, a white man had accumulated a great store of precious, merchandizable goods. If only he could get them to Europe his fortune would be made. To further this purpose, he hired the best African porters he could find and one morning, having eaten, they assumed their burdens and set out, hoping to rendezvous with a ship that would be lying off the coast at the full of the third next moon. They weren’t only strong men, these men he had hired. They were happy men. And, singing their ancestral songs as they walked, they were brave men. They didn’t turn back, or so much as look back, at the borders of their tribal lands. Even in a seemingly endless savannah they were, happily, for going on. By the full of the second moon the white man was sure they would make it to the coast in time. Then one morning a strange thing happened. Strange, that is, to the white man. Sitting there, not eating, their eyes closed, the porters, to a man, sank into a trance. By midday that day, the man who must at all costs make his fortune was bullish. By midday three days later, he was totally at a loss. In the end, every ruse and remedy he could think of having failed, he sat beside one of them and, his bearing and tone altogether more accommodating, he asked him, Will you please tell me what is happening? Slowly, over hours, the porter came back from his trance. Yes, he said, I will tell you. During the past two and a half

moons we have moved so far, so fast, that now, trance deep in ourselves yet awake, we must sit here and wait till our souls catch up.

That’s the story.

In Europe during the past three centuries, we too have moved too far too fast. It is time, I believe, to do as the Africans did.

Among the first peoples of the world, loss of soul is thought of as the great illness. Only the most powerful shamans can deal with it.

Ever since Freud, however, the peoples of the West have talked and talked about suppressed sexuality, but have talked hardly at all about suppressed soul.

The question is: are we ill with the great illness? And, if not in our nature, are we, in our behaviour, aids virus to the Earth? Are we doing to the Earth what the aids virus does to the human body: are we breaking down its immune system? Is the Earth HIV Positive? Is it HSS Positive? Homo sapiens sapiens positive?

I don’t know.

Anyhow, that is one way of looking at this book. Disengaging from movement local, it invites us to give movement essential a chance. […]

ENGWURA NOW

Paradise Lost

Between nature’s

Pink period and blue

We were Fauns, we looked on.

Being cold, apriori and few

We turned towards time at will

And we watched the yew

With wide eyes.

That it might see us,

Understand,

We solved the earth.

That it might see us,

Show its hand,

We blitz the rock

With metaphors,

We blitz the land.

Again and again in the European tradition we encounter the belief that the world we live in is a lower world and that our souls have fallen or declined or wandered downward into imprisonment in it.

Speaking, confusedly it would seem, of world soul and individual soul, Plato says:

Soul taken as a whole is in charge of all that is inanimate and traverses the entire universe, appearing at different times in different forms. While it is perfect and winged it moves on high and governs all creation, but the soul that has shed its wings falls until it encounters solid matter. There it settles and puts on an earthly body …

Speaking of the incarnate, fallen soul, he says:

… we see it in a state like that of Glaucus the sea-god, and its original nature is as difficult to see as his was after long immersion had broken and worn away and deformed his limbs, and covered him with shells and seaweed and rock, till he looked more like a monster than what he really was.

In some moods, Plotinus is sure:

The human soul next: everywhere we hear of it as in bitter and miserable durance in body, a victim of troubles and desires and fears, and all forms of evil, the body its prison or its tomb, the Cosmos its cave and cavern.

It has fallen: it is at the chain: debarred from expressing itself now through its intellectual phase, it operates through sense, it is a captive; this is the burial, the encavement of the soul.

Life here, with the things of earth, is a sinking, a defeat, a failing of the wing.

Among Gnostics, there were some who believed that the soul was cast down, others that it had wandered down. For all of them, however, they being pneumatikoi, life in a body was imprisonment in a body and the world of their everyday experience was a netherworld:

I am a Mana of the great Life. Who has made me to live in the Tibil, who has thrown me into the body-stump?

A Mana am I of the great Life. Who has thrown me into the suffering of the worlds, who has transported me into the evil darkness?

Grief and woe I suffer in the body garment into which they transported and cast me.

My eyes, which were opened from the abode of light, now belong to the stump. My heart, which longs for the Life, came here and was made part of the stump.

As the souls descend they draw with them the torpor of Saturn, the wrathfulness of Mars, the concupiscence of Venus, the greed for gain of Mercury, the lust for power of Jupiter; which things effect a confusion in the souls, so that they can no longer make use of their own power and their proper faculties.

Looking down from the highest summit and perpetual light, and having with secret desire contemplated the appetence of the body and its life so called on earth the soul by the very weight of its earthly thought gradually sinks down into the netherworld. […] In each sphere (which it passes) it is clothed with an ethereal envelopment, so that by these it is in stages reconciled to the company of the earthen garment. And thus it comes through as many deaths as it passes spheres to what here on earth is called life.

Rescued from Manichaean pessimism during the Renaissance, the doctrine helped to sanction a sense, not of helplessness and corruption of man, but of the dignity of man. Indeed, it sometimes sanctioned a sense of man as Magus. Intending a benign outcome, Prospero commands the elements. In Hamlet, however, these same elements are a mortal coil and, world-weary, he reaches not for the wand but the bare bodkin.

In Henry Vaughan, the doctrine becomes vision:

I saw Eternity the other night

Like a great ring of pure and endless light,

All calm as it was bright;

And round beneath it Time, in hours, days, years,

Driven by the spheres

Like a vast shadow moved; in which the world

And all its train was hurled.

In Blake, the doctrine is pervasive. In his exposition of it, the soul follows the Serpent out of Paradise and, the gates closed behind it, it sinks into a state of visionary and therefore existential contraction and opacity:

Now I a fourfold vision see

And a fourfold vision is given to me

Tis fourfold in my supreme delight

And threefold in soft Beulah’s night

And twofold always. May God us keep

From single vision and Newton’s sleep.

In declension from Eden the soul passes downward through Beulah, Generation and Ulro.

In Ulro, perceiving it as we do, we do to the world what Medusa does to it. Solidly inhospitable to them, therefore, it echoes our metaphors and cosmologies back to us.

In Ulro the subjective-objective divide is absolute. Or, rather, it is experienced to be absolute. Between subject and object there is no corpus callosum, no corpus sympathicus. We are in other words as far as we can be from the ‘sumpatheia ton hollon’, the ‘sympathy of all things for all things’ that some Stoics and some Romantics were aware of:

She shall be sportive as the fawn

That wild with glee across the lawn

Or up the mountain springs:

And hers shall be the breathing balm

And hers the silence and the calm

Of mute, insensate things.

The floating clouds their state shall lend

To her; for her the willow bend;

Nor shall she fail to see

Even in motions of the storm

Grace that shall mould the maiden’s form

By silent sympathy.

Ulro is something we are. It is something we do. It is only in cultural superimposition that it exists objectively.

Enthusiastically in the seventeenth century, many Europeans followed Midas and Medusa, their Moses and their Aaron, into Ulro.

In them and through them, Ulro established itself as norm.

Like the children of Israel in Egypt, we have lived since then in hard bondage. In hard philosophical bondage to the Ulro categories of our European understanding, to the Ulro forms of our European sensibility.

It is time to imagine and yearn for an exodus.

It is time to believe and know that mind altering alters all.

Uvavnuk was an Inuit medicine woman.

I imagine her coming down into Ulro.

Her voice old as Altamira, old as Lascaux, I imagine her singing her song to us:

The great sea has set me in motion

Set me adrift

Moving me as a weed moves in a river.

The arch of sky and mightiness of storms

Have moved the spirit within me

Till I am carried away

Trembling with joy.

Our exodus. Our path through the sea. Our path through Europa’s Europe into the Pleistocene, pristine Earth.

Initiates into the mysteries of Mithras climbed what they called the Klimax Heptapylos, an ascent through seven gates representing the seven planets.

The only klimax or ladder we need is a ladder without rungs, a ladder that leaves us where we are.

Where we are, had we but eyes to see it, is the highest Divine.

In the processio Dei ad extra near and far are equally divine.

In the processio Dei ad extra the sea-smells of Glaucus and the smell of frankincense are equally divine.

In the processio Dei ad extra Styx and star are equally divine.

Not where the wheeling systems darken

And our benumbed conceiving soars –

The drift of pinions, would we hearken,

Beats at our own clay-shuttered doors.

The clay, in our case, is culture. Mostly culture.

In our case the clay is Europa’s Europe. The Europe of Manes, Plato and John of Patmos.

It is time to take down your ladder, Diotima.

It is still there, still set up, in Melencolia’s house.

And, win or lose at the city’s Dionysia, it is time to announce a new banquet, Agathon.

Invite Uvavnuk.

Invite Kunapipi and Indjuwanydjuwa.

Invite Black Elk.

And Glaucus – invite Glaucus. The smell of the seaweeds and the sea will keep things grounded.

How good it would be if Lao Tze could come. Aruni also. And Yajnavalkya.

Teachers such as these will teach the teachers of Hellas, the teachers of Europe, so it might be no harm to invite a small audience of eminent Athenians – Socrates, Pericles, Plato, Euripides and Thucydides.

We need to be healed.

As far back as Athens.

As far back as Jerusalem.

As far back as Rome.

We need of course to be healed as far back as Olduvai. That far back and farther. But it will be a good night’s work indeed if we are healed, or began to be healed, in our Hebrew, Greek and Roman past.

So what shall the topic for discussion be?

A topic proposed by Uvavnuk, seconded by Lao Tze.

That the weed’s way of being in the river

Should be our way of being in the world.

Two latecomers to the banquet, Jacob Boehme and William Blake, will have something to say.

Boehme: He to whom time is the same as eternity, and eternity the same as time, is free of all adversity.

Blake: Tho’ driven away with the Seven Starry Ones into the Ulro, yet the Divine vision remains everywhere forever, amen.

Leaving next morning, Aruni proposes another topic for another night: that the processio Dei is a procession outwards not outside but within and with the Divine.

Sir Orfeo and Lady Eurydice

And raising my visor

In Ireland I saw

Every field, every flower

Had a here-lies look

And the wind

From the snake-bitten ocean

Was cold.

In an old towered town,

Completing my dream,

I searched for a name

No headstone had heard of,

In old mirrors I searched

For the face I had dreamed of.

For a year in that town

I was tongued from the throat,

I told the old lies.

But the night we touched hands

We longed for the woods

And like nightingales there

We were tongued from the hips.

Crab-tracks I left on Silurian shores, searching for something.

A gorgeous snake nature I shed. And all my snake knowings. I left all my snake’s eggs in a hole high up in my brain and went on, on all fours, searching for something.

I was a bear cub, the only survivor. In her high rock shelter she gave me suck. She was the last. I drank the last drop of Neanderthal milk. Into the night I loped, searching for something.

One night I knew:

I was snake too soon

I was mammal too soon

I was human too soon

And now I was shaman. A red enchantment in Pleistocene caves.

Conjuring bison

Conjuring ibex

Conjuring horses with my neighings.

A bison in a bison trance-dance.

One night the eggs in my head hatched out.

All my snake nature, all my snake knowings. A gorgeous snake nature. Gorgeous snake knowings.

I wasn’t one thing any more.

I was Medusa.

I was Mucalinda.

Mucalinda and Medusa went separate ways into separate cultures, east and west, and I was a broken chiasmus.

A broken callosum between the Mesozoic and the Kainozoic in me, Mucalinda and Mara in me, Buddha and bear in me.

Buddha wouldn’t drink Neanderthal milk and the bear wouldn’t read the Lotus Sutra.

My human face

was

My African mask,

My Shaman’s mask,

My mask of the Mesozoic.

Every night was Halloween night. I was scared. I was shaman. I was the scooped out turnip of my tribe. After dark, when my nightmares showed, when my Mesozoic mind showed, I scared the dead, I scared diseases out of my people. Into great forests I scared them, into great waters. But madness stayed. Lunacy stood its ground. Every night was Halloween night. Disease and the dead were afraid of me, I was afraid of myself.

A scooped-out terror I was to myself. I hid from myself in bear caves.

Snake too soon. Mammal too soon. Human too soon. Thrown together too soon. With no Chiasmus. No corpus callosum. Only a face. A human face. A face that came off every night with my clothes.

Human too soon. Prophet too soon. Saint too soon.

I went back to the Ring of Brogar and prayed:

One thing or other God

Centaur me or Sagittarius me,

Griffin me or coffin me,

Cobble me God,

Cobble cock and snake together in me,

Cobble eagle and lion together in me,

Griffin me God,

Cockatrix me,

One thing or the other God

Centaur me or Sagittarius me,

Thy will be done.

Like a house broken into I was when the Cross broke into me.

It grew in me,

Was Chiasmus in me,

Was corpus callosum in me.

Heaven and hell, Buddha and bear, Mucalinda and Medusa were one lovely morning in me, one lovely evening in me.

Up through the cultures I came. Across them I came.

I was a peasant,

I was Blanchefleur,

Before Bluebeard was I had a blue beard.

I was Sir Gawain:

And Raising my visor

In Ireland I saw

Every field, every flower

Had a here-lies look

And the wind

From the snake-bitten ocean

Was cold.

That’s what it means, the Cross. It is corpus callosum to all that we are. It brings all that we are into marvellous oneness. To begin with that’s what it does.

After Good Friday the door to Vrindavan is open. The road to the hills where Shepherd and the Shulamite meet is open.

But the night we touched hands

We longed for the woods

And like Nightingales there

We were tongued from the hips.

Opposites

In shadows I crossed

With philosopher kings,

I craved a corrupt,

A cavelight lover.

In the Christian cold

And catacomb

You would fight the flesh

To the bitter end,

From the mammal ascend

To the marble mother.

‘There is all Africa and her prodigies in us.’

Sir Thomas Browne

‘In man lies all whatsoever the sun shines upon, or

heaven contains, as also hell and all the deeps.’

Jacob Boehme

A dream: I am walking in Soho. I turn into Old Comptom Street. A few doors down I walk into a striptease club. I’ve been here many times. I know the place well. As I expected, the striptease is going on upstairs. I can hear the music. The ground-floor has changed. And I am surprised. I look on in wonder. Instead of the lurid billboards and equally lurid lady at the reception desk I’d been used to, there are now five or six long rows of clothes racks. And all the clothes are unisexual. It is this that causes me to be in a state of silent wonder. I see no one. I’m aware of my own aloneness. I leave.

Walking up Wardour Street, I’ve a four-pronged farm fork in my hand. There are scales of dry cow-dung on the prongs. I’m no longer in the city. I’m in an eighteenth-century park. It becomes a vast savannah. There’s a patch of ground that looks different from its surroundings. I begin to dig. I uncover three granite steps. I climb down. Reaching the lower step I find myself looking down on an oceanarium. On the other side, so far away I can hardly see him, I see a man standing at the edge of the water. Bending down he touches something under the surface of the water. Whatever it is he touches begins to rise. Effortlessly, of its own accord, it rises. In a moment I see what it is. It’s a great iron grid. It rises out of the water. Something vast, something suppressed, is rising beneath it. Continuing to rise the grid folds itself flush with the embankment I’m standing on. Up from the floor of the ocean below, I see an immensity rising. As it rises, I see it’s an immense tangle of living things. Draped across it all, undulating, so that now it is manifest, now it isn’t, is a great snake-form. It’s a dogfish I say. That’s what it is. It’s a dogfish. Never have I seen anything so stupendous. Under it’s outrageously arrogant skin are tropics and tundras and taigas and summers and sunsets and dawns of aliveness. All the dreams the galaxies haven’t yet got around to dreaming are there. The undreamed and the dreamed, the unmanifest and the manifest, the noumenal and the phenomenal, the night of Brahma, and the day of Brahma are undulations of the same Great Ouroboros. The suppressed Ouroboros rises and under its undulations, rising, is an im-mense tangle of living things.

Far away and far, far below at the edge of the oceanarium I am. I’m standing where the man originally stood. I think that I am that man. An otter comes towards me walking. It would be a calamity I feel were he to bite my small toe. I withdraw my foot out of harm’s way. The otter passes me. He doesn’t bite.

I’m sitting on the water. An abyss it is now, not an ocean. Without looking I see that there’s a great Mesozoic reptile behind me. It is mindless and ugly. It is getting ready to lunge at me and swallow me. It makes vicious, darting movements in every direction. Then it steadies itself, facing me. It opens its vast, mindless mouth. This is it I think. I’m finished. But there’s nothing I can do. I can only wait. It opens its mouth still wider. It lunges furiously towards me but, at the last moment, when I’m already in the shadow of the deepest pit of perdition, it veers away becoming as it does so a harmless, shy, little animal going about its business. I wake up.

At the time I dreamed this dream I most desperately needed good news about me. And now at last me psyche was saying fear not. The repressed had returned and I hadn’t gone mad. That much I more or less instantly understood.

Later I was tempted to think that the dream had implications for our religious past.

I imagined a religious past in which

Marduk didn’t slay Tiamat,

Apollo didn’t slay Python,

Yahweh didn’t slay Leviathan.

’Twas as if all the dragon-slaying Gods of the ancient Near-and-Middle East had heard Jesus. At the end of his night in Gethsemane, Jesus commanded Peter to put up his sword. At this moment Peter wasn’t only Peter the apostle. He was every dragon-slayer who had at anytime attempted to lobotomize the psyche, to lobotomize the Earth.

Is it possible that after Gethsemane we should think not of Yahweh slaying Leviathan, but of Yahweh lying on the coils of Leviathan.

Is it possible that as Hindus think of

Vishnuanantasayin

so we can think of

Yahwehleviathasayin.

Anyway, Beast and Abyss aren’t as incorrigibly hostile as we’ve imagined them to be.

We don’t need to slay the one or to set up bars and doors against the other.

The repressing grid can go up, the restraining bars and doors can give way, and we aren’t destroyed.

The repressing grid went up in Job, the restraining bars and doors gave way in him, yet there he is, the one through whom we inherited the promise:

‘For thou shalt be in league with the stones of the field, and the beasts of the field shall be at peace with thee.’

We have a new past to emerge from.

In Buddha’s Footsteps

By a fire escape I go

From these gables and facades,

From things that suffer spring

In a trembling, bringing forth.

Leaving weeping walls

And all walled walking,

I walk down to a stream,

Through three wet gardens.

There in the shade of a living oak

My fingers seek your old, old hair

And I set pensive down,

Once having touched your face.

And yet your eyes belong not here,

Nor hereafter if we meet

And the moonlight meets your hair,

For in Eden one evening

You cast a short shadow

And the child in you feared

The half moon was your fault.

Afraid of the wisdom,

The wingspan of words,

We saw love through his eyes

And the priest-king talked

For the tongue-tied stars.

But once it was night,

Once one of his mirrors

Had stolen your face,

The road out was ours

And the only angels there

Were sown

By our footsteps sobbing behind us.

But I could tell Death

I have loved you and so

I am deeper than scythes.

I could even tell Christ,

Although I am all body,

All second-hand head,

I’m a Christian again

But I’ve opened my mind,

I have opened my gates,

Long ago, to God’s horses.

Conception is a closing down, a returning of our ostrich heads and hearts to the blinding sandheap of empirical hearing and seeing.

It is startling to hear from the Tibetan Book of the Dead that we are conscious accomplices in our own conception. Accomplices, with karmic propensity, in our own diminution.

New Yorkers go to a head shrink. Shrink my head, sir. Make my head small. What will you charge, sir, for making me small. Small enough, so small, that I can go out and become a big tycoon in Wall Street or a renowned professor of anthropology in the city university.

In the sidpa bardo I had no head to shrink. But I shrank nonetheless. My head is my shrunkenness. The great human head that European humanists are so proud of is an eclipse.

An octopus ink cloud of hearing and thinking and seeing, that octopus ink cloud I projected, and the octopus ink cloud I projected I am.

There is, however, something more to me, although not as me, than this little I, this little eclipsing I am.

In me, always, is the possibility of an awakening.

In this awakening I see the eclipsing, the ink cloud, that I am. I see that every eye and I is an ink cloud eye and I, an eclipsing eye and I. A desire not to be this eclipsing eye and I is born. A desire for self loss in Brahmanirvana is born.

Conception is a closing down. And for most of us nowadays, life in society makes that closing down more dense. Gross national product requires of us that we be brain bright only. Living, as it does, like some ancient God, off the odour of sacrifice, it requires of us that we be brain deep only in our psyches.

Because of the air that is trapped in it, an otter’s coat underwater is waterproof.

Of ourselves we might ask: is there a reality we have no experience of, even though, throughout our whole lives, we are submerged in it? What reality are we reality-proofed against? Proofed against what reality all around us are we in our dreaming and waking, in our mescalin highs and peyote lows?

In our bliss trips and bum trips?

A tree whose sap is creosote I am.

Creosoted within against all forms of inwardness that would threaten or upset or destroy my ego identity. Creosoted also against all forms of outwardness that would do likewise.

Against what within them and about them are archangels creosoted by the vision of God that beatifies and blisses them? Against what within them and about them are demons creosoted by their black burning?

Against what am I creosoted in virtue of existing as a separate, self-conscious identity? Against what am I creosoted in virtue of being an experiencer? What does experiencing creosote us against? What does the subjective-objective divide creosote us against?

Suppose all this weather proofing against hostile osmosis from within and without, against visionary overwhelmings from within and without, supposing all this weather proofing against forms of inner and outer encounter we aren’t able for, supposing it dissipated and I survived unharmed, supposing all my immunities disappeared and, amazingly somehow, I knew I had no reason now to stand afar off, like the children of Israel, from the mountain of God on fire before me or from any Tutankhamen tomb of revelations, locutions and visions opening within me, supposing that whenever I wished I could be a swooning Shulamite to all the depths and heights of inwardness, to all the depths and heights of outwardness, supposing all this were the case, what then? Wouldn’t that be the end of all seeking? Wouldn’t that be the highest good? Wouldn’t we be wasting our blessed Shulamite time if we listened to anyone who suggested otherwise? But Buddha suggested otherwise, and ever since his Fire Sermon in the Deer Park millions of people have continued to listen to him.

Out of the overflowing bliss of heaven they come, the seven lean oxen of Pharaoh’s dream. Out of Eden and out of the garden of spices they come, lowing, lowing, lowing.

Famine lowings at the heart of all relatedness. All relatedness is one side of an open wound facing the other. There is no final healing in relatedness. Even at the heart of our Song of Songs, at the heart of it somewhere, beyond hearing maybe for the moment, is a lean lowing.

A lean lowing at the heart of all things that are in relatedness, a lowing and a neighing. Buddha heard the lowing. At the heart of Indian sensuousness he heard it. He heard the neighing and he rode out.

Hindus think of the Buddha as an incarnation of Vishnu.

In him Vishnuanantasayin grew into Mucalinda Buddha, Mucalinda Vishnu.

As this poem sees it, Mucalinda Buddha challenges us to a new kind of sanctity.

The sanctity not of Mary crushing the serpent, but of the Buddha in his coiled protections.

Mary crushing the serpent stands for the sanctity of exclusion and repression.

Buddha in the protective coils of the serpent stands for the sanctity of inclusion and integration.

Yet again, we have a new past to emerge from.

Coming Forth by Day

The road I took

Kept turning back

Finding darker ways to go.

It was night and to show

No shadow had come

Its original scalp covered the stone

And all night long my skin was mine

A sleeping bag of flesh and bone.

When all roads stopped

At the skyline’s scythe

And the moon like a moving whimper

Wandered past

I asked

But the sun could not make room

I asked

Which child is pregnant with me

In which Mother’s womb

And went on

Till my ladder lost

Its remaining rung

And the red waves rose

And talked to the stars

In their mother tongue.

As this poem conceives it, our journey to the heavenly elsewhere, to paradise lost, is in the end a journey to where we are. But we mustn’t, for that reason, think that the journey was wasted effort, and of little moment. On the contrary, it was, more than likely, a stupendous journey, every step of it necessary to bring us to where we already were.

Reaches of it were logged long ago by the Ancient Egyptians, were logged in

The Book of Caverns

The Book of Gates

The Book of Two Ways

Biblically, reaches of it were logged in

The Book of Psalms

The Book of Job

The Book of Jonah

‘Save me from the lion’s mouth, for thou hast heard me from the horns of the unicorns.’

‘Our heart is not turned back, neither have our steps declined from thy way, though thou hast sore broken us in the place of dragons and covered us in the shadow of death.’

‘Fearfulness and trembling are come upon me, and horror hath overwhelmed me.’

‘Thou hast shewed thy people hard things, thou hast made us to drink the wine of astonishment.’

‘Save me, O God, for the waters are come into my soul, I sink in deep mire where there is no standing, I am come into deep waters where the floods overflow me.’

‘I am counted with them that go down into the pit.’

‘Thou hast laid me in the lowest pit, in darkness, in the deeps.’

‘I am shut up, and I cannot come forth.’

‘Thy fierce wrath goeth over me, thy terrors have cut me off. They came round about me daily like water: they compassed me about together.’

Like chonyid bardo terrors are the terrors of Job:

I will speak in the anguish of my spirit: I will complain in the bitterness of my soul. Am I whale or a sea, that thou settest a watch over me? When I say, my bed shall comfort me, my couch shall ease my complaint, then thou scarest me with dreams, and terrifiest me through visions, so that my soul chooseth strangling and death rather than life.

And Jonah’s wasn’t an uneventful voyage:

The waters compassed me about, even to the soul: the depth closed me round about, the weeds were wrapped about my head. I went down to the bottom of the mountains, the earth with her bars and doors was about me forever: yet hast thou brought up my life from corruption, O Lord, my God.

Throughout it all the Tibetan Book of the Dead would be saying, Fear not, O nobly born: it is your own thought forms you are encountering; it is your karmic propensities, become visually manifest, that are now terrorizing you. As dream terrors are they: they cannot and they will not harm a hair of your head.

And not all reaches of your road home are terrible.

‘Blessed be the Lord, for he hath shewed me his marvellous kindness in a strong city.’

‘For great is thy mercy toward me, and thou hast delivered my soul from the lowest hell.’

‘He maketh my feet like hind’s feet, and he setteth me upon high places.’

‘My cup runneth over.’

Of the heaven states and the hell states of which we are rapt on this journey, Theologia Germanica has this to say:

This hell and this heaven come about a man in such sort, that he knoweth not where they come; and whether they come to him, or depart from him, he can of himself do nothing toward it.

It is indeed a stupendous journey. Stupendous in the awful but loving intensities of its purifying fires.

This is what St John of the Cross has to say:

This shows how great is the mercy of God to the soul when he thus purifies it in this strong lye and bitter purgation, as to its sensual and spiritual part, from all its affections and imperfect habits in all that relates to time, nature, sense and spirit; by darkening its interior faculties, and emptying them of all objects, by correcting and drying up all affections of sense and spirit, by weakening and wasting the natural forces, which the soul never could have done of itself, as we shall immediately show. God makes it die in this way to all that is not God, that, being denuded and stripped of its former clothing, it may clothe itself anew.

Himmatia, Plotinus calls them, these old clothes. Himmatia and, less often, kitones.

Were we, with Hindus, to call them koshas, then we would, by implication, be acknowledging our need to go through the dark night of the soul.

Koshas are obscurations or veils. But, unlike Salome’s veils, they aren’t veils that we wear, they are veils that we psycho-somatically are.

Putting it brutally: conscious and unconscious, psyche is the blind not the window.

It is a blind of awareness-of.

It is a blind of dreaming-and-waking-awareness-of.

And that is why the Mandukya Upanishad would lead us beyond waking and dreaming and dreamless sleep – leading us beyond this latter because, although dreamless sleep isn’t a state of awareness-of, it is nonetheless a state of psyche and as such isn’t Divine Ground.

Translating this into the Christian story: the Mandukya Upanishad leads us to Golgotha. It leads us in other words to the summit or Hill of the Koshaless Skull.

On Golgotha our koshas walk out on us. Waking awareness-of walks out on us. Dreaming awareness-of walks out on us. Dreamless sleep walks out on us. We are left looking down into the empty skull, our own skull.

This is Tenebrae

This is Tehom

This is Turiya

This is the bliss of our reception back into Divine Ground.

On Easter morning we can say it: first there was a mountain, then there was no mountain, now again there is a mountain.

The mountain hasn’t changed. But how changed we are. In our seeing how changed.

In our being and seeing we have come forth.

Looking at the mountain now we know there are two Easters: an Easter in which we awaken to the extraordinary and an Easter in which we awaken to the ordinary.

Altogether more marvellous than the Easter in which we awaken to the extraordinary is the Easter in which we awaken to ordinariness.

That’s what we know, having come forth.

In our capacity for ordinariness is our final sanctity.

Mona Melencolia Europa

Then autumn came

And the last quarter

Of last November’s moon

Was there beneath the trees

Mirrored beneath the leaves

In a garden pool.

And the night the moon had set

And all night fruit failed

We watched the pool subside

Seeking the dark beneath what seems.

And over its doors,

Standing over its own

Pale face in the water,

We saw the next night

That our castle had pined.

And your flesh was soft,

Full of coffin comfort,

You cried for the cold,

The chronic dead.

Afraid of the face

I was hiding behind

The stars kept their distance

They were still superstitious

And the moon when it came

Had a price on its head.

Where the stars were our thoroughbred

Brothers, we bowed,

An old queen in the West,

You admired your own woes.

Admiring the rose

And the nightingale’s voice

We were glad above all

That our fingers were blind;

We were glad

There was so much

Deaf flesh on our bones.

(Thinking of Leonardo’s ‘Mona Lisa’ and Dürer’s ‘Melencolia’ and Blake’s ‘Hecate’ as portraits of Europa – portraits, that is of a civilization in progressive trouble.)

A dream, dreamed consciously: I’m alone in the Louvre at night. I’m standing in front of Mona Lisa. You’re a fine woman I’m saying to her. A fine woman and a grand woman. Your eyelids, your eyes, your smile, your veil, your hair, everything everyone finds marvellous in you I find marvellous too. I’d love to be your Pygmalion. Nothing I’d like better than to come home from work some evening and find you sitting by the fire waiting for me. But, I don’t know if you know it, sitting there as you are you are blocking my view of the world behind you, you’ve eclipsed it. You’re a blind between us and the world. Is there any chance you would move aside. You could stand out here with me and the two of us then could look at the world. For centuries now you’ve had your back to the world. ’Twould do you good I’m sure to turn round and look at it. To walk back into it. Back into the mountains. Back to where thunder is. And wonder. And water. Water in streams. Water in rough rivers. Water in gorges. Water in waterfalls. I imagine you walking back. Growing smaller and smaller. In the end you are only the size of your own first footprint. It is turned the other way now. You are walking into the mountains. Into Tao. In the mouth of the final valley you look back and I know what your smile means: the human head blocks the view. It was never meant to fill the whole frame.

Weary of the humanist hands that made you, weary of the humanist eyes that looked at you, you left your face, as Christ left his, in Leonardo’s napkin or canvas, and walked on, retracing your steps, till your own first footprint became your chrysalis, your boatman and boat, transforming you, carrying you into the high wild mountains you had turned your high Renaissance back to for so long.

Mona transformed. Mona Melencolia Europa regenerated.

She sees the mountain she lives on as Kuo Hsi would see it. He painted mountains as though they were clouds.

And there she is now, an old, old woman. Can you see her? That’s her. Matchstick size, she is crossing a bridge under her mountain. How like Kuo Hsi’s great mountain it is. Looking up at it, she doesn’t see gnarled protuberances of matter. She sees gnarled protuberances of mind in hibernation.

That’s it.

Mona Lisa transformed is our Renaissance transformed.

It is Quattrocento again and Kuo Hsi’s mountain is our Parnassus.

The High Renaissance room in the Louvre.

Room in which Leonardo’s Mona smiles at us.

Room in which Leonardo’s Baptist points the way.

Great room. Great ship. High Renaissance ship in which we would sail into Salvation. Humanist salvation.

Out at sea a storm broke. In the jaws of Death the sailors sought answers. They cast lots. And yes, it fell upon him, the Baptist, the one who had pointed the way. Seizing him, they heaved him overboard, over the sides of his universe, into the maw of Leviathan. Turning flukes, Leviathan sounded, carrying him down and yawning him out into the Deep below all depths, into the silent vast no-thing-ness of it, into the na rupam, na vedana, na samjna, na samskarah, na vijnanam of it. Down into the Deep we are so biblically frightened of he was carried. Down into the Deep the Bible calls Tehom. He didn’t go mad. A vast and very sacred sanity dawned upon him. From within him it dawned, and in its light he saw that

TEHOM IS TURIYA

And there he is now.

Like Jonah now.

Like Jonah Anadyomene.

And he points to a Christ Piero Della Francesca’s Risen Christ hasn’t yet caught sight of. He points to a Christ Christianity has yet to open a Mandukya door to.

Our Mandukya door to Kuo Hsi’s mountain.

Our Mandukya door to the next Renaissance.

TENEBRAE NOW

Fifth Story

It was after closing time and Martin was proud of God.

‘That’s the long and the short of it now,’ he declared, ‘I’m proud of God.’

I managed him up the steps. We were almost at the door when he stopped, elaborately, not going a foot farther.

‘Give me your hand,’ he said.

‘Lave it there,’ he said.

‘My besht friend,’ he said.

‘The coldesht day in winter,’ he said, ‘and the hottesht day in summer.’

Knowing that I wasn’t appeased, he looked up at me forlornly:

‘No use hangn a man without a head, John. No use hangn a man without a head.’

‘No, Martin, no.’

No.

I managed him through the hall door, out into the night.

Even in the dark he was proud of God. ‘Thanks be to God and his Blessed Mother, we had a hishtoric booze. Thanks be to dh’Almighty Redeemer we had a brave drink, in brave company, and John! do you know John, I’d shtand naked in the shnow lishtnen to that one. A lovely girl she was, John. A lovely girl and a grand girl and sure tishnt from the wind she took it, don’t I know all belongn to her for four generations back.’

‘The song she sang, John, sing that song.’

I sang one verse:

‘And how proud was I of my girl so tall,

I was envied mostly by young men all

When I brought her blushing, with bashful pride,

To my cottage home by Loch Shileann side.’

‘Lave it there,’ he said, shaking my hand.

‘’Twas a hishtoric booze, wazhnt it, John?’

‘’Twas Martin, ’twas.’

Shaking my hand, he assured me again, whatever the weather, he would be with me. On the coldesht day in winter he’d be with me. With me, if I needed him, on the hottesht day of summer.

We made it as far as the stand of trees. He wanted a smoke. We sat down.

Holding the lighted match vertically for a moment, it bloomed into an unflickering, perfect flame. It didn’t illuminate the dark. Making way for it, the darkness of this dark December night withdrew from a brief distraction it had no need of.

And I wondered: would the universe be a brief distraction to it also?

Drawing hard on his pipe, having with difficulty put the lid on it, he retrieved, as much from his suddenly beneficent memory as from his overcoat pocket, the half bottle of whiskey he had bought.

I knew we’d be here for a long time.

Having oilskins on, I lay back on the leaf-strewn, twig-strewn earth under the trees, lime trees and chestnuts.

Come next April, this will be a sea of daffodils, I thought. A sea, it will sometimes seem, of yellow consciousness. In comparison, the consciousness with which we run the world, the consciousness we have settled for, will seem dull and grey. Can we believe Hindus and Buddhists? I wondered. Deep down in our own inner soil, in our thought-strewn, dream-strewn, desire-strewn soil – are there, deep down in us, bulbs of other kinds of consciousness? Bulbs that, given a chance, would bloom like Martin’s match? Bloom in our darkness? Lotuses of other kinds of consciousness, crimson consciousness, sapphire-blue consciousness, blooming in the aqueous and vitreous humours of our eyes. I thought of the water lilies in the lake above at Lisnabrucka, their roots in the mud, their stems reaching up through the water, their blossoms in sunlight. Is it possible, I wondered, that I’ve never risen above the mud? When will my chakras open?

‘You ha’ me kilt, John,’ Martin said. ‘You ha’ me kilt. Never once have I seen you at the holy mass in Roundstone, and you a grand man and a fine man and a great neighbour. You ha’ me kilt, not believn in God, man or the divel.’

‘All whom it may concern,’ he said. ‘All whom it may concern …’

I knew that whatever it was it was intended to particularly concern me.

‘There was a man down Carna way one day, John, sittn on the sea-wall he was, smokn his pipe. A tourisht car came along and shtopt and the man who was drivn rolled down the window and ashkt, “Am I on the right road to Carna?” The Carna man took his pipe out of his mouth, he looked up the road and down the road and then, lookn at your man in the car, he said, “You are, yeh, you’re on the right road to Carna, but you’re turnt the wrong way.”’

‘I’m on the right road alright, Martin. That’s what you’re telling me isn’t it? I’m on the right road to heaven but, and ’tis a big “but”, isn’t it Martin, I’m turnt the wrong way.’

‘’Tis against your own feet you’re walking, Martin.’ I was trying to manage him across the cattle trap at the end of the avenue.

‘Whisht,’ he said. ‘Whist, John. God bless you, John, you’re one way is one way but I can’t help it can I if my one way wants to be every way?’

Awkwardly, all ways, we crossed over.

‘I’m as drunk as a nine-wheel cart, John.’

‘I know, Martin.’

Eyesight in this kind of darkness was a bad habit. Wholly ineffective though it was, it nonetheless distracted attention from hearing and touch – from information coming to us through our feet.

‘Where are we, John?’

‘On the back road.’

‘Where’s that?’

‘At Ballynahinch.’

‘Ballynahinch!’

‘Yeh.’

‘The corns is killn me.’

Knowing what this meant, I ignored the remark.

‘Not long now till Christmas, Martin.’

‘Christmas!’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m lamed, John.’

Having pity for him, but against my will, I groped my way, groping the air, to the side of the road and I sat him down on a low wall. I sat down myself.

‘Where are we?’

‘At the stable.’

‘The shtables.’

‘Yes.’

‘God be with dh’oul shtables, God be with dh’oul shtables. Many and many and many is the fine bucket of fine cow’s milk Ted and mesel milked in them oul shtables. Ted and mesel. Ted and mesel. The Lord have mercy on Ted, the Lord have mercy on Ted, the Lord have mercy on Ted – Say it, you son of a bitch, say it.’

‘The Lord have mercy on Ted,’ I said promptly.

The thought of it, Ted dead and buried below in Carna, it was all too much for him. He took to the bottle.

Given how the mood had changed, it was a sob of light that bloomed from his matchstick now. Briefly perfect, it died on its way to the bowl of his pipe.

And the whiskey wasn’t helping.

‘Wings I thought twould give me, John. But no. Fins it gave me. The fins of an eel it gave me. I’m an eel in a boghole, John.’

Is there, I wondered, thinking of Martin and me sitting there on a low wall in front of the old stables, is there a desolation that is independent of us? A desolation of the time or of the place. A desolation of the night. Up the road it had come and here we were, our mood inexplicably changed. We had a pipe, a sob of light, and a whiskey bottle. And we had two antiphons, the first being, the coldesht day in winter and the hottesht day in summer, the second being, no use hangn a man without a head.

It was our midnight mass. Our mass for the dead.

It was our mass for all that was dead in ourselves.

It was our mass for the bulbs that never sprouted in us.

It was our mass for the sea of yellow consciousness that never bloomed in us.

Kyrie eleison

Kyrie eleison

Kyrie eleison

No use hangn a man without a head.

No use hangn a man without a head.

No use hangn a man without a head.

No, not on a night as dark as this.

And yet it wasn’t a destitute dark. Or a bereaved dark.

It didn’t yearn to be sown with stars. A sense I had, walking beside the most silent reach of the Owenmore River, is that the metaphysical is sensuous, so sensuous that, its presence once felt, hearing, seeing, touch, taste and smell swoon away, knowing themselves to be empty distractions.

It occurred to me, crossing Lowry’s Bridge, that we needed a hymn tonight. But I didn’t give it much thought, because, here in Connemara tonight, Night was having its Easter. We were walking in an Easter of darkness. An Easter of Divine Darkness. The Dark as it was before it was trivialized by starlight and sunlight.

‘Happy Easter, Martin.’

‘Are you there, John?’

‘I am, Martin.’

‘Where are we?’

‘At Lowry’s Bridge.’

‘I’m as drunk as a nine-wheel cart, John.’

‘Me too, Martin. Me too. I’m as drunk as the nine-wheel cart that has come for to carry us home.’

Coming out onto the road to Derrada, Martin wanted to go left.

‘No, Martin, no,’ I said. ‘That’s the way to Ballinafad.’

He erupted. No whorin Kerryman would tell him the way home.

‘Don’t I know the place like the back of my hand. Washnt it here, right here at six o’clock one morning, that I met my father and mother, me comin from a wedding or a wake in Emlaghmore, and them, the two of them, drivn two cows before them to the auld cow’s fair in Clifden. John! God bless you John, the random is on you …’

It was a long argument.

In the end, taking command, I stood him in the middle of the road and said, ‘Now, Martin, that’s your right ear, isn’t it? And in it you can hear the sound of the Owenmore River, can’t you? And knowing this place as well as you do, knowing it like the back of your hand, you know that the road along the river is the road to Derrada, you know that, don’t you, Martin?’

Having won the argument, I felt sorry for him. Hoping it would mollify him, I reminded him of the song the young woman had sung. I knew he would ask me to sing it. I sang it.

‘Fare thee well old Ireland, a long farewell,

My bitter anguish no tongue can tell,

For I’m going to cross the ocean wide

From my cottage home by Loch Shileann side.

At the village dance by the Shannon stream,

Where Blind O’Leary enchantments played,

No harp like his could so cheerily play

And no one could smile like my Eileen gay.

And how proud was I of my girl so tall,

I was envied mostly by young men all,

When I brought her blushing with bashful pride

To my cottage home by Loch Shileann side.

But alas! our joy ’twas not meant to last,

The landlord came our sweet home to blast

And he to us would no mercy show

And he turned us out in the blinding snow.

And no one to us would then open their door,

O God! your justice, it was rich and sore,

For my Eileen fainted in my arms and died

As the snow fell down by Loch Shileann side.

Then I raised my hands to the heavens above,

I said a prayer for my life’s lost love,

O God of Justice, I loudly cried,

Revenge the death of my murdered bride.

Then I laid her down in the churchyard low

Where in the springtime sweet daisies grow;

I shed no tears, for my eyes were dry

As the snow fell down by the graveyard side.

So fare thee well, old Ireland, fare thee well, adieu,

My ship is taking me away from you,

But where e’er I wander my thoughts will bide

At my Eileen’s grave by Loch Shileann side.’

‘Enchantments played,’ Martin said, lingering as though he were himself enchanted by every syllable.

We had a new antiphon

en-chant-ments played!

en-chant-ments played!

Our midnight mass was growing.

We had already crossed Dervikrune Bridge when a sheep coughed on the side of Derrada Hill.

‘What ails you?’

‘Nothing, Martin. Nothing. ’Twas a sheep that coughed.’

‘One of Petey’s sheep?’

‘Yes.’

‘Hooze, I suppose.’

‘Or fluke?’

‘Fluke. Musht be fluke.’

He stopped, his head bowed. ‘The Lord have mercy on Petey,’ he said. ‘The Lord have mercy on Petey.’

‘Yes,’ I said, instantly, ‘the Lord have mercy on Petey.’

‘Petey Welsh!’ he said. ‘A great neighbour was Petey. Petey was up there on Derrada Hill one day, a hill he walked every day, after sheep, but this day, no matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t come down out of it. Thinkn that he had maybe stepped on a foídín mearaí, he took off his coat, turned it inside out, put it back on, and now, with the greatest ease in the world, he found his bearings, walked down the hill, and in his own door.’

‘Foídín mearaí, you call it, Martin?’

‘That’s what it’s called, the sod of confusion, the sod of bewilderment. Tis well known they are out there, such sods. Shtep on one of them and you’ll wander around bewildered and confused all night till the moon comes up, or you’ll wander around, the random on you, till you take off your coat and put it back on, inside out.’

‘Even if we take off our natures, and put them back on inside out I don’t think we’ll reach home tonight, not at the rate we’re going, Martin.’

He didn’t answer.

‘How are you, Martin?’

‘Never better. And yourself?’

‘Fine, Martin, fine.’

‘My besht friend, John. Lave it there,’ he said, breaking free from me. ‘Lave it there,’ he said, shaking my hand. ‘The coldesht day in winter and the hottesht day in summer.’

‘That’s right, Martin.’

‘Tis, John, tis.’

‘The river has a lovely name, hasn’t it Martin?’

‘The river?’

‘Yes.’

‘You mean the Owenmore?’

‘Yes. The long, long flowings and the little falls of the Owenmore.’

‘The Owenmore?’

‘Yes, Martin. The long, long flowings and the little falls of the Owenmore would be soul to someone who came here having no soul at all.’

‘No soul at all?’

‘I had no soul at all, none that I was aware of, when I came here, Martin.’

‘What was that?’

‘A salmon, Martin. A salmon leaped.’

‘A salmon?’

‘Yes.’

‘Salmon is whores, John. Ted and Mickey and Josey and mesel was up here poachin one night. We set the nets but then the thunder came, three or four big rolls of it and that was it. We knew that was it. We went home without a shcale. You know that, don’t you? Salmon sink to the bottom when there’s thunder. On a night of thunder twould take an otter to frighten them out of their lie, into the nets.’

‘How are you, Martin.’

‘Not good. To tell you the Chrisht’s truth I’m not good. I’m by no means good. Tis like being blind.’

‘Should we turn our coats inside out?’

‘No.’

‘No.’

‘No. No use. Where are we?’

‘At the quarry.’

‘I don’t believe it.’

‘We’re at the quarry, Martin.’

‘I’ll not believe it.’

‘It’s alright, Martin.’

‘We could be somewhere awful.’

‘We could be, Martin, but we aren’t. We are passing the quarry.’

‘You’re shtubborn.’

‘’Tis you that’s shtubborn, Martin.’

‘We’ll sit down.’

‘No, Martin, no, we won’t.’

‘We’ll wait for mornin.’

‘We won’t, Martin. God bless you, Martin, God bless you and spare you, but try to keep walking. We’ll make it, Martin.’

‘We’re losht!’

‘We aren’t.’

‘Where are we?’

‘We’re at the quarry.’

‘I see no quarry.’

‘Alright, Martin, alright,’ I said. I stood him now again in the middle of the road. ‘Can you hear the river, Martin? Can you hear the near roaring? That’s the roaring at the eel weir. And the roaring farther on, can you hear that farther roaring, that’s the roaring at Ted’s place. Below Ted’s place is Lynne’s place. Below Lynne’s place is my place. Round the corner from my place is Petey Welsh’s place. And up the bohreen from Petey Welsh’s place is your place.’

‘Places! Places! Places! You have me mezhmerizhed with places! Where are we?’

I faced him towards the quarry wall, or what I presumed was the quarry wall, and I told him to look straight ahead.

Staggering forward a little, he stood there, his hands resting on his knees, peering into the void. He was looking hard. I could sense how hard he was looking. He looked for a long while. At last, recognizing something, he half called, half wailed, ‘John! Are you there, John? Are you there, John? Oh John, sure I know well where we’re now, John. I know well where we’re now, John. But where! the fuck! are we?’

Sitting by my revived fire, having left Martin home, I attempted, if only initially, to come to terms with Martin’s answer.

Is the whole world, I wondered, a foídín mearaí? Is every lobe of the human mind, dreaming and waking, a foídín mearaí? And the easy assurance we almost always have of knowing where we are in terms of our whereabouts, is that, because it is so unsuspected, the most serious of all our bewilderments? I imagined it this way: asleep one night, here in my house in Derrada West, I slip into a dream. In the dream I experience myself to be in Iran, walking in arid country south of Isfahan. A man who comes towards me asks me, where am I? A few miles from Isfahan in Iran, I say, pointing to the blue dome of the Majis-I-Shah mosque. While my hand is still pointing I wake up and to my astonishment I’m not in Iran at all but in my room in Derrada West.

Waking up from dreaming. Waking up from waking.

Waking up from waking I realize that I’m not in a universe at all. I’m in the void. The void that is void of worldly reality. Cartographers of the universe are cartographers of that void. And so it is that I imagine myself talking to a modern astronomer, Carl Sagan, say.

‘Astronomers have been looking at the universe for a long time now, Carl. During the last three centuries ye have been looking at it through optical telescopes and, more recently, ye have been listening to it through radio telescopes. Could you tell me, where are we?’

‘Well’, I imagine Carl saying, ‘the universe is composed of galaxies. Some of these galaxies are in clusters called megagalaxies. One of these galaxies is called the Milky Way. It is a spiral galaxy. It has a hundred million stars in it. On the outer arm of the spiral there is a star we call the sun. Circling about the sun are nine planets. The third planet out is called the Earth. That’s where we are.’

To which I reply, ‘Are you there, Carl? Are you there, Carl? Oh! sure I know well where we’re now Carl. I know well where we’re now, but, knowing where we are in terms of our whereabouts, what kind of knowing is that? One day, waking up from waking, you will find yourself pointing at the void.’

The only antiphons I was left with going to bed were

enchantments played,

enchantments played,

foídín mearaí,

foídín mearaí.

Lying there, too frightened to sleep, I calmed and consoled myself with a Hindu parable:

Narada was a solitary. So altruistically motivated was he in his long and perilous quest for the Truth, that one day it was Vishnu, the Great God, the Great Mayin himself, who was standing in his door.

‘Conscious of all that you have endured on behalf of all things,’ Vishnu said, ‘I have come to grant you the boon of your choice.’

‘The only boon I have ever wished for,’ Narada replied, ‘is to understand the secret of your maya. It will please me, Holy One, if you show me the source, and the power over us, of the World illusion.’

As if to dissuade him, Vishnu smiled, strangely. But, having named his boon, Narada remained silent.

‘Come with me,’ Vishnu said, his strange smile not fading. Before long the arid land they were walking in had turned into a terrible, red desert. Moisture in their mouths was turning to ashes. Like the cracked rocks their minds were cracking.

Claiming he could go no farther, Vishnu sat down.

Seeking water for his God, Narada struggled on. To his great delight, the desert gave way to scrubland, the scrubland gave way to sown land and then, in a valley below him, there it was, a lovely green village.

He knocked on the first door. So enchantingly beautiful was the young woman who opened it that he instantly and entirely forgot what it was he had come for. It was strange. As if this house had always been his home, he sat and ate with the family. Early next morning he was working in their fields with them. At seed-sowing he worked. At harvest he worked. In the quiet time between seasons, he asked her father if he might have the young woman’s hand in marriage. Three children were born to them, and when the old man died Narada became head of the household.

One year the monsoon rains were like the rains at the end of a world. Night or day there was no let up. The river burst its banks and struggling one night to reach the safety of higher ground, Narada’s wife was swept away. Wailings in the chaos of waters was the last he heard of his three children. He was swept away himself but, miraculously, not to drowning. He was sitting on a hill. So terrible and red was the glare he couldn’t open his eyes. Moisture in his mouth was turning to ashes. Like the cracked rocks, his sanity was cracking. Then, from behind him, he heard a voice, familiar but enigmatic: ‘I’ve been waiting for almost a half an hour now, did you bring the water?’

Our Hindu parable.

Our Hindu

Ite, missa est.