1 THESSALONIANS

INTRODUCTION

I believe if the apostle Paul could be transported from the first to the twenty-first century and appear on television, the interviewer would introduce him with a résumé that would go something like this:

We’re thrilled to have with us today the apostle Paul, a man who probably needs no introduction. He’s the apostle of apostles, a church-planting entrepreneur who has founded thriving ministries all over Europe, an expert on healthy marriage and family relationships, an author of numerous best-selling books, and a sought-after speaker whose messages have inspired millions!

All the while Paul’s face would turn from the ashen color of revulsion to the crimson of embarrassment. Then, as the camera zooms in on Paul himself, his look of dismay would give way to a polite smile. He’d dismiss the flattering introduction with a wave of his hand and set the record straight:

I’m the last —and least —of the apostles. Not even worthy of the title, if you ask me. I am no church-planting entrepreneur (whatever that is). In fact, I couldn’t have done any of it without my co-laborers at my side . . . and I probably have broken more ministry leadership rules than all of them put together. And I don’t know where you get that “marriage and family” expert thing —I’m not even married and prefer the single life. As far as authoring numerous books, I almost always have had help; I wrote letters, not books, and if somebody made money off of them, it sure wasn’t me! And that thing about being a sought-after speaker? Well, my preaching has gotten me kicked out of town, beaten, arrested, and stoned! In fact, I’ve been called “unimpressive” and “contemptible” in my speech. Sir, I don’t know who you’re introducing, but it doesn’t sound like me!

Clearly, before we launch into Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians, we need to put things in the proper perspective. We need to make sure we don’t paint a picture of Paul’s life and ministry that bears no resemblance to the way it actually was. It’s a classic case of the tension between idealism and realism. If the road of Christian life and ministry is paved with hardship, suffering, struggle, and anxiety, we need to describe it that way. If we, instead, imagine it as an ideal of constant success, comfort, happiness, and tranquility, how hard it will be to deal with the real thing! In 1 Thessalonians, Paul deals with life and ministry the way they really were for both his ministry team and the Thessalonians, the way they are for all faithful Christians, and the way they ought to be as we overcome trials and temptations that come our way.

KEY TERMS FOR 1 THESSALONIANS

orgē (ὀργή) [3709] “wrath,” “anger”

When people hear the word “wrath,” they often think of God’s angry disposition against sin or of ultimate eternal punishment of the lost (1 Thes. 2:16; see also Rom. 1:18). However, in the other two instances in 1 Thessalonians, Paul tends to use the term “wrath,” orgē, in reference to temporal, earthly judgment, especially the final judgments leading up to the second coming of Christ (1 Thes. 1:10; 5:9). Oftentimes we refer to this specific period of wrath as “the Tribulation” or “end times.”

pistis, agapē, elpis (πίστις, ἀγάπη, ἐλπίς) [4102, 26, 1680] “faith, love, hope”

Commonly called the “theological virtues,” this trio forms the foundation of the Christian life in Paul’s writings. In 1 Corinthians 13:13, he notes, “Three things will last forever —faith, hope, and love” (NLT). Several years earlier, when he wrote to the Thessalonians, these three also played a central role in his letter (1 Thes. 1:3; 5:8). In Paul’s writings, pistis refers to faith, confidence, reliance, or trust —not only the starting point of the Christian life (Eph. 2:8), but especially in 1 Thessalonians, the foundation of Christian living (1 Thes. 1:3, 8; 3:2, 6, 7, 10; 5:8). Love (agapē) in 1 Thessalonians is associated with faith and characterizes the relationship between believers in the Thessalonian church and the nature of the work they do as a result of their knowledge of Christ Jesus. The concept of hope (elpis) has particular significance for Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians, as it turns attention upward and forward to the return of Christ and the ultimate realization of our blessings (1:3; 2:19; 4:13; 5:8).

parousia (παρουσία) [3952] “presence,” “coming,” “advent”

The second coming of Christ is a major theme revisited directly or indirectly in every chapter of 1 Thessalonians (1:10; 2:19; 3:13; 4:15; 5:23). Though the term parousia can have a neutral sense of physical “presence,” when Paul uses it in reference to Christ, it is used “of his Messianic Advent in glory to judge the world at the end of this age.”[1] Though the parousia of Christ is an object of fear for the wicked, it is an object of hope and joy for Christians.

parakaleō (παρακαλέω) [3870] “encourage,” “comfort,” “console,” “help”

Prior to His crucifixion, Jesus promised His disciples that when He ascended to heaven He would send a “Helper” (paraklētos [3875]), God the Holy Spirit, who would teach them (John 14:26), bear witness about Jesus (John 15:26), and be with them forever (John 14:16). In Paul’s understanding, the ministry of the Holy Spirit is worked out in the church through the believers He indwells (1 Cor. 12:4-11). It should be no surprise, then, that Paul uses the verb parakaleō throughout his letter, connected with other words for “imploring,” “exhorting,” “strengthening,” and “building up” (1 Thes. 2:11; 3:2; 5:11). As the community of the Spirit, the Great Encourager, a primary purpose in Spirit-filled ministry is to encourage one another (4:18).

THE THESSALONIAN STORM AND ITS LASTING EFFECTS

About a year had passed since a storm of persecution had swept Paul, Silas, and Timothy from the city of Thessalonica. In the wake of the storm, the budding church in that city was left bent, weary, and underdeveloped. They needed more light from the Son to dry their weary and weathered leaves, to strengthen their wilting limbs, and to bear healthy fruit.

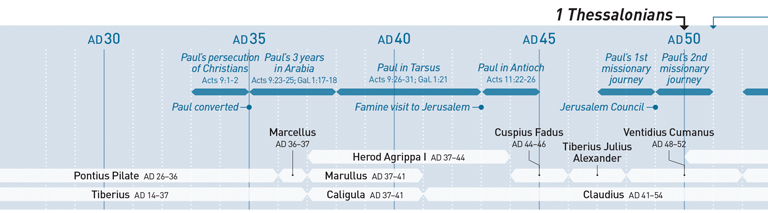

Here’s what happened. Following the first missionary journey (Acts 13:1–14:28), a council of apostles and church leaders met in Jerusalem to discuss and soundly reject the false teachings of the Judaizers, who were legalists extraordinaire (Acts 15:1-35). Between the first missionary journey and the Jerusalem Council, Paul wrote his letter to the Galatians from Antioch, encouraging the young churches he and Barnabas had planted to stand strong against the threat of such legalism. After the council, with its written decision firmly in hand, Paul determined to retrace his steps and revisit the churches: “Let us return and visit the brethren in every city in which we proclaimed the word of the Lord, and see how they are” (Acts 15:36). However, when Paul and Barnabas had a falling out over whether to take John Mark, the two decided to part ways (Acts 15:37-39). Instead of taking Barnabas with him on the second missionary journey, Paul chose Silas (also called “Silvanus”) as his right-hand man in ministry (Acts 15:40).

A SNAPSHOT OF ANCIENT THESSALONICA

1 THESSALONIANS 1:1

In 315 BC the Greek general Cassander, who later became king of Macedonia, founded Thessalonica. It later developed into a major commercial seaport and military launching point.

At the time of Paul’s second missionary journey (around AD 49–52), Thessalonica was the capital and most populous city of Macedonia, boasting over two hundred thousand people. Situated on flourishing trade routes both by land and sea, the city was a bustling center of commerce. William Barclay points out the strategic importance of such a city for the spread of the gospel: “If Christianity was settled there, it was bound to spread East along the Egnatian Road until all Asia was conquered and West until it stormed even the city of Rome. The coming of Christianity to Thessalonica was crucial in the making of it into a world religion.”[2]

The ruins of the agora, a Roman shopping center, in Thessalonica, built around the first century.

As a free city in the Roman Empire, Thessalonica enjoyed some level of self-governance of its affairs without constant interference by the emperor. Such a prized status, however, could have been lost if the city’s leaders failed to maintain peace and security . . . or if the Romans suspected sedition and rebellion. Both of these charges were leveled against Paul and Silas by the raucous mob that the Jews had stirred up against the Christians (Acts 17:6-7). In that episode, Thessalonian politics, economics, and religion were turned against the Christians, leaving the young church in a state of uncertainty.

Along the way, Paul and Silas met a young man named Timothy in Lystra. As the son of a family of faith, Timothy enjoyed an excellent reputation among the believers (Acts 16:1-2). Obviously impressed by him, Paul invited young Timothy to participate in their missionary ventures. Though Paul seems to have originally had in mind a modest journey of edifying already-established churches, the Spirit had something else in mind. As their attempts to enter various regions were frustrated by the Spirit of Jesus (Acts 16:6-8), they were pushed farther and farther west through Asia Minor until they reached the coast of the Aegean Sea. (See the map “Paul’s Second Missionary Journey” on page 2).

At that point, something unexpected happened. At night, Paul received a vision instructing him to cross the sea into Macedonia and to preach the gospel there (Acts 16:9-10). Sailing from Troas and through Neapolis, they reached the city of Philippi, where the Lord softened the hearts of many to accept the gospel of Jesus Christ (Acts 16:11-15). However, in Philippi the closed, hardened hearts of spiritual opponents turned the city leaders against Paul and Silas, eventually leading to their arrest, beating, and imprisonment (Acts 16:16-24).

Luke uses a unique term, politarchēs [4173], for the rulers of Thessalonica, a word which appears only in Acts 17:6, 8. In 1877 an inscription (pictured here) was discovered in excavations of ancient Thessalonica that used this same term in reference to the city rulers.[3]

After a miraculous deliverance from jail that resulted even in the salvation of the Roman jailer and his family (Acts 16:25-40), Paul, Silas, and Timothy left Philippi and traveled to Thessalonica in order to proclaim the coming of the Messiah at the Jewish synagogue in that city (Acts 17:1). The truth of the gospel won over more and more people, especially among the God-fearing Gentiles who had been hanging around the synagogue for years but had not officially converted to Judaism. When the Jewish synagogue leaders saw both Jews and righteous Gentiles converting to Jesus as the Messiah, they became jealous (Acts 17:5). In response, the opposing Jews mustered a pagan posse from the marketplace but searched in vain for Paul and Silas. So they rounded up a handful of new Thessalonian believers and played the game of guilt by association: “These men who have upset the world have come here also; and Jason has welcomed them, and they all act contrary to the decrees of Caesar, saying that there is another king, Jesus” (Acts 17:6-7). After this frightening episode, Paul and Silas were forced to leave the city by night, having been banned from Thessalonica (Acts 17:9-10).

After several months away from their fragile church plant, Paul and Silas “could endure it no longer” (1 Thes. 3:1). They sent the young Timothy to Thessalonica to check on the believers’ welfare. But if Paul and Silas were so concerned with that fledgling church, why didn’t they just put their ministry in Athens or Corinth on pause and take a trip back north to Macedonia to provide some assistance? Why send Timothy —the youngest and most inexperienced member of their ministry team?

The fact is, a legal pledge Jason made on behalf of the church in Thessalonica (Acts 17:9) likely involved the promise that Paul and Silas, as the named perpetrators of unrest, would not return to the city. And in all probability, it likely included a substantial sum of money in the form of a bond that would have been forfeited had Paul and Silas returned to town. In any case, when Timothy returned from his trip to Thessalonica, Paul and Silas were thrilled to hear of their spiritual health even in the midst of persecution. In response, the three of them wrote a letter to the church in Thessalonica from Corinth to affirm their steadfast faith, to exhort them to excel even more, and to inform them about what to expect in the future as they awaited the Lord’s return.

OVERVIEW OF THE LETTER

Although rather brief, Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians is one of the most positive and insightful portrayals of a first-century congregation. The faith, love, and hope of the Thessalonian Christians were downright contagious. In Paul’s desire to encourage believers, his basic message spanned all the tenses of salvation: from the past, into the present, with a view toward the future. In fact, the basic message of 1 Thessalonians might be summed up this way: Live in faith, love, and hope in light of the past and in view of the future.

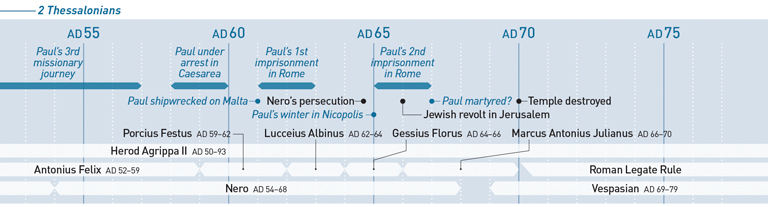

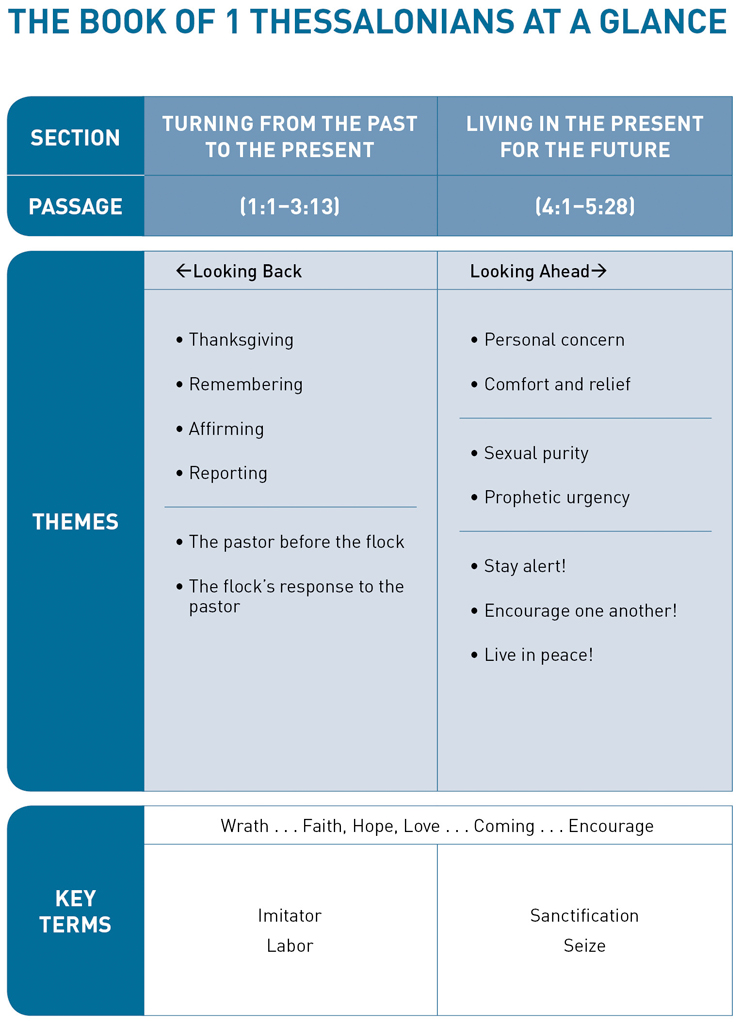

The book can be divided into two major sections.

Turning from the Past to the Present (1:1–3:13). In this section Paul mentions the Thessalonians’ faith, love, and hope in Christ (1:3), recalling crucial events in their past: their powerful reception of the gospel (1:5), their imitation of the apostles’ life and ministry (1:6), and the example of faith, love, and hope they had become for the whole region of Macedonia (1:7-10). By reminding them of his own ministry style among them (2:1-12), Paul encourages them to endure suffering in the work of ministry just as he did (2:13-20). To Paul’s relief, the Thessalonians’ past seeds of faith and love had not only endured persecution and hardship, but had actually grown and blossomed in the present beyond his expectations (3:1-13).

Living in the Present for the Future (4:1–5:28). In the second part of the letter, Paul exhorts the Thessalonians to continue to live holy lives in light of their hope in Christ’s return. Beginning with straight talk about moral purity (4:1-8), he moves on to encourage them to love one another and to live properly among outsiders as outworking their faith and love (4:9-12). Then, in a powerful passage on the second coming of Christ, Paul reminds the Thessalonians of the hope they have of rescue from wrath, resurrection from death, and reunion with fellow believers when the Lord Jesus returns from heaven to live with His church forever (4:13–5:11). Yet this reminder of Christ’s return wasn’t given simply to inform them about the future, but to transform them in the present. So Paul ends this brief but glorious epistle with rapid-fire exhortations to live in faith, love, and hope in light of the past and in view of the future (5:12-28).

Paul’s Second Missionary Journey. Paul and Silas preached in Thessalonica during their second major journey around Asia Minor, which extended into Macedonia and Achaia (present-day Greece). Some of the Jews there attacked the believers in Thessalonica because of Paul’s message, so Paul and Silas escaped and continued on their journey. Later, they would write to the believers in Thessalonica from Corinth.

THE BOOK OF 1 THESSALONIANS AT A GLANCE |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

SECTION |

TURNING FROM THE PAST TO THE PRESENT |

LIVING IN THE PRESENT FOR THE FUTURE |

|

PASSAGE |

(1:1–3:13) |

(4:1–5:28) |

|

THEMES |

Looking Back |

Looking Ahead |

|

|

|

||

KEY TERMS |

Wrath . . . Faith, Hope, Love . . . Coming . . . Encourage |

||

Imitator Labor |

Sanctification Seize |

||