In basic economics, supply and demand are typically the primary drivers of prices, and with less expensive items that do not require financing, this is the predominate principle. However, with purchases that are typically financed, the interest rate of the debt instrument becomes another major factor. The purchases of real estate and businesses are normally financed, and interest rates fluctuate mostly based on the discount rate set by the Federal Reserve (the Fed) in the United States. The discount rate is the rate at which banks borrow money from the Fed. They may also borrow from other institutions at the Fed, and that rate is known as the federal funds rate. Those trades often occur overnight between depository institutions, which are the institutions with surplus balances that lend to those that need funds.

Low interest rates effectively raise the cost of real estate, so when interest rates rise, values can be expected to drop. For a proper perspective on this, two extremes can be considered. At one extreme, if there were no loans to purchase it, the value of real estate would drop significantly. Under that scenario, if every piece of real estate could be purchased only in cash, there would be very few people who could afford it, and those who had to sell would eventually have to lower their prices to that new paradigm.

At the other extreme, if loans had an interest rate of zero percent, if they required no down payment, and if they were available to everyone regardless of credit rating or income, values would rise because demand would increase. New buyers with bad credit and without funds for a down payment would be able to buy a home rather than rent.

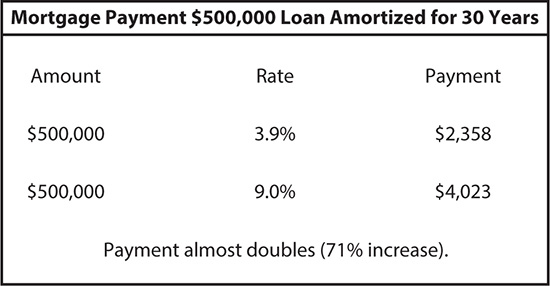

What would prices be under each scenario? Because the U.S. economy is credit driven, most buyers of real estate look at the monthly payment rather than the total cost. Thus, prices would plummet in the first scenario and skyrocket in the second. For instance, as shown in Exhibit 11.1, a $500,000 mortgage amortized for 30 years would have a monthly payment of $2,358 at 3.9 percent. That same mortgage would have a monthly payment of $4,023 at 9 percent, which was a normal rate for many years in the past. Therefore, price fluctuations are based on the interest rate paid (also known as the cost of money) and the availability of credit, both of which are to a great extent controlled by the government and, more specifically, the Federal Reserve Bank. To reiterate, the Fed indirectly causes mortgage lending rates to go up or down by setting the interest rate that banks are charged for borrowing from it.

Mortgage Payment on a $500,000 Loan Amortized over 30 Years

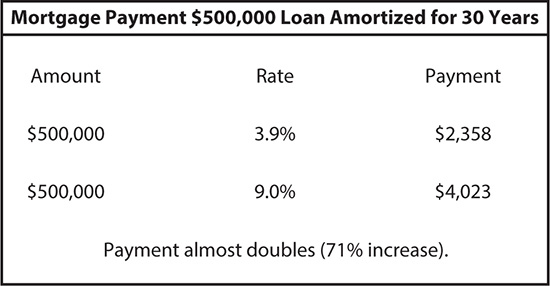

Historically, the last time rates were pushed to an extreme was under President Jimmy Carter in the late 1970s and early 1980s. At that time the United States was experiencing increasing inflation, and to stem it, the Fed raised rates until a mortgage might cost 18 percent or more. This rate increase did limit inflation, but it also slowed real estate sales and business loans, and lending slowed to a dribble, causing financial failure for many business entities and throwing the country into a recession. The spike in that time period is shown in Exhibit 11.2, which is a chart showing the history of interest rates over the period of 1962 through 2012.

Interest Rates from 1962 Through 2012

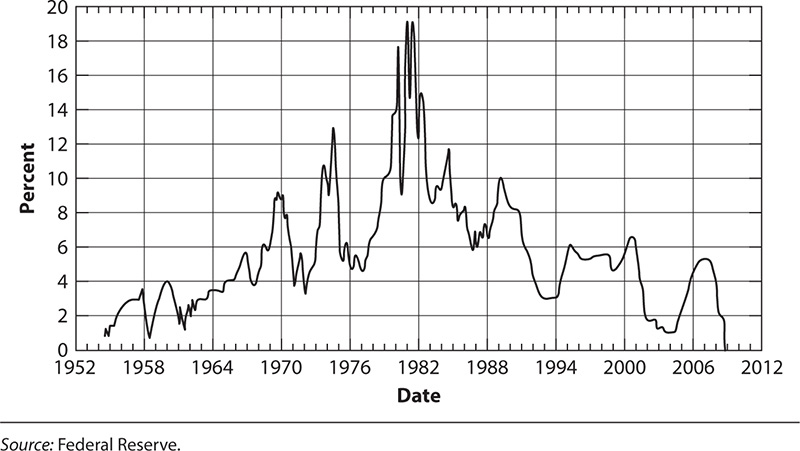

Another result of low interest rates is the effect it has on savers. People who rely on income from savings see their incomes drop drastically when rates plummet. For instance, a person who has $1 million in the bank will see a substantial change in income when rates are low. One of the most risk-free investments is an FDIC insured fund. As shown in Exhibit 11.3, when an FDIC insured certificate of deposit (CD) or money market rate is about 0.7 percent, it will return an annual yield of $7,000. When the rate is 5 percent, the yield will be $50,000 a year. When the rate is 9 percent, the yield will be $90,000.

Rate of Return on a $1 Million CD

As the rates decrease, more savers seek riskier investments to keep the yield up, and this is where real estate is affected. Historically, when significantly better returns are available for investment real estate than for savings, property prices are driven up, only to come down when the bubble in value bursts. And this is particularly true for single-family houses. In the bubble that burst around 2006, 25 percent of the homes bought were for investment purposes.

Another by-product of the low rates is overborrowing—particularly in the business sector. When money is cheap, businesses tend to spend more and expand when they might not have otherwise. The consequence of this is that many companies that invest in expanding production in an overheated economy later find demand falling and rates going up simultaneously. They continue to have higher fixed operating costs as the demand for their goods is diminishing. This is why in some industries, when there is overexpansion, factories and machinery and equipment can drop precipitously when the economy enters a recession. One example is the solar industry, which at one point was expanding production just at the time the economy was ebbing. Moreover, many government subsidies for solar installations around the world diminished or were terminated, making the product so noncompetitive that it lost its appeal in the marketplace.

Another aspect of this phenomenon is that most business loans are not long-term loans, and when rates increase, many lenders will not renew current loans, which can put even a viable business in a predicament. Commercial loans are similar in that they are normally made with a renewal period of every 3 to 5 years, but they are amortized over a longer period, generally 20 to 25 years. Lenders generally tell commercial borrowers that renewal will not be a problem when the loan is made, but things can change when real estate values decrease.

Government programs that essentially subsidize real estate purchases or certain industries can produce an artificial market that may collapse. Federal Housing Administration (FHA), Veterans Administration (VA), and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) real estate loans generally require a lower down payment than conventional loans, and because of this, they tend to drive values up. They may also set up buyers for failure by allowing them to buy with such little equity that the market has to decrease only slightly to put these buyers “upside down” with their mortgage—which means they owe more than the property is worth. In the same way, programs to finance certain industries, such as the example of solar power, can induce overproduction and riskier investments than would normally be considered prudent.

If certain government policies are having an impact on the market of the subject property being reviewed, the reviewer needs to understand how these properties are affected in determining if the appraisal is accurate. Appraisal has been defined as the present worth of future benefits, and in many cases those potential benefits will be determined by the status of government programs and subsidies.