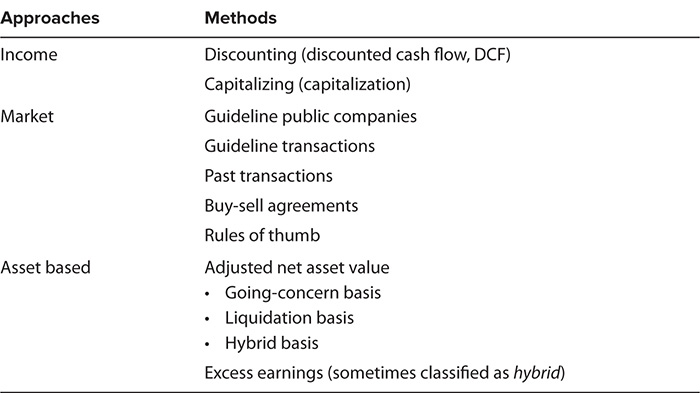

The classification of business appraisal methodology is somewhat arbitrary because the methods are not totally discrete. Nevertheless, organizing the classification of methodologies can be helpful in both implementing and reviewing the appraisal process. The classification of methodology as presented in this chapter, while not followed universally, is representative of a growing consensus on the taxonomy of business appraisal. The balance of this book is generally organized to follow this classification.

Business appraisers usually try to use two or more appraisal methods to maximize the reliability of the final result. They may give different relative weights to different methods or conclude that one appraisal method is dominant in a given situation.

When business appraisers implement different methods, they usually try to make the data and procedures used in each method as discrete as possible from those used in the other methods, in order to reach the different indications of value as independently as possible.

There is, however, necessarily some interrelationship among the methods. Each method is based on some form of economic income, and/or asset values, and all depend to some extent on market data. For instance, the income approach uses expected economic income while the market approach may use both historical and expected economic income. The asset approach uses adjusted asset values for all assets, while the income and market approaches may use asset values for excess or nonoperating assets. The income approach derives its discount and capitalization rates from data extracted from the market. The market approach uses market-derived multiples of some form of economic income variables and/or asset values.

Business appraisers capitalize income in both the market and income approaches, but they develop their capitalization rates in different ways. In the market approach, capitalization rates come from direct observation of specific market transactions. In the income approach, capitalization rates are developed through a cost-of-capital model using broad market data. The asset approach develops its adjusted asset values from market data.

In reviewing descriptions of different appraisal methods, the reviewer should think about the extent to which each method is really an indication of value independent of another method, or whether the appraiser is simply presenting the same data in different formats. For instance, the use of a market multiple of book value of equity in the market approach and the use of the book value of equity in the asset approach as separate indications of value are actually one and the same method.

The professional business valuation community has generally adopted a hierarchy of the terms to complete an appraisal. They are: approach, method, and procedure:

• Approach is, in the broadest sense, an accepted means of achieving a valuation result.

• Method refers to general ways of implementing the approaches.

• Procedure means the specific calculations, data used, and other details involved in a specific method.

The three approaches recognized in business valuation are essentially analogous to the three approaches used in real estate appraisal:

1. Income approach. Valuing the business or business interest on the basis of some form of expected economic income stream—in real estate appraisal, usually called “capitalization”

2. Market approach. Valuation of the business or business interest by reference to other transactions—in real estate appraisal, usually called the “comparable sales approach,” or “sales comparison approach”

3. Asset-based approach. Valuation of the business on the basis of assets and liabilities—in real estate appraisal, usually analogous to something like the “cost approach”

Within each of the three approaches, there is reasonably broad consensus on the terminology used to denote the methods employed.

Discounting. Projecting the expected economic income over the life of the investment and discounting each increment of that expected income back to a present value at a rate of return is known as a discount rate. This method is also known as the discounted cash flow (DCF) method. (The procedures are similar to the method known as yield capitalization in real estate appraisal.)

Capitalizing. Observing or estimating a single period’s economic income and dividing it by a rate of return known as a capitalization rate. This method is also known as the capitalization method. (The term is almost analogous to direct capitalization in real estate appraising, except that it is adjusted for the growth rate.)

Guideline Public Company Method (Sometimes Called the Comparable Company Method). This method involves deriving valuation multiples from prices and financial data for company stocks traded in the public market and applies the multiples to the appropriate financial data of the subject company. No counterpart exists in real estate appraisal because there is no organized market for fractional interests in real estate.

Guideline Transaction Method. This method involves deriving valuation multiples from prices and financial data of public or private companies that have been sold and applying the multiples to the appropriate financial data of the subject company. This method is analogous to the comparable sales approach in real estate appraisal. (Some might further subdivide this method based on whether the company was public or private before the sale.)

Past Transactions Method. This method uses multiples of financial data from the company’s own past transactions:

• Past change of ownership of 100 percent or a controlling interest in the subject company

• Past transactions of minority interests in the subject company

• Past acquisitions made by the subject company

• Past offers (but must examine whether the offers were bona fide and arm’s length)

Buy-Sell Agreements. This method has been placed arbitrarily under the market approach with the idea that someone negotiated and agreed to the buy-sell terms for the subject at some point in the past. Depending on the purpose of the valuation and the terms of the buy-sell agreement, its valuation provisions may range all the way from completely controlling to irrelevant. The weight, if any, to be accorded to the valuation terms of the agreement is often a critical decision.

The agreement may be controlling for some valuation purposes and not for others. Sometimes, the degree of weight may depend on the extent to which the agreement was arm’s length when negotiated. Often the appraiser and/or the court decides that the terms of the buy-sell agreement are a factor to be considered, but they are not controlling.

Rules of Thumb. Ballpark ranges of possible values are derived from simple formulas used in an industry. Sometimes classified under the market approach because the rules are allegedly market derived, the rules of thumb are generally applied without support from any body of underlying market data.

Adjusted Net Asset Value (ANAV) Method. The appraiser adjusts all of the company’s assets (both tangible and intangible) and liabilities to their current value, usually fair market value, and subtracts the liabilities from the assets based on the following premises:

• Going-concern premise. All assets and liabilities are adjusted to the current fair market value in continued use, and the liabilities are subtracted from the assets.

• Liquidation premise. All assets and liabilities are adjusted to fair market value on a liquidation premise of value, and all the liabilities and liquidation costs are subtracted from the assets.

• Hybrid premise. Assets are valued with the expectation that they will be in continuing operation on a going-concern basis and non-operating assets will be valued on a liquidation basis. This could involve more than one operating unit of the business, where each operating unit is valued on a going-concern basis and non-operating assets are valued on a liquidation basis. This latter version is sometimes called a breakup method or disaggregation method.

Excess Earnings Method. The appraisal adjusts only the company’s tangible assets to current value—again, usually fair market value in continued use—and subtracts the liabilities to obtain a net tangible asset value. The appraisal estimates the amount of income needed to support the net tangible assets. If there is income over and above that amount, the excess income is divided by a capitalization rate to estimate the value of the company’s intangible assets. The appraisal adds the estimated value of the intangibles to the value of the tangible assets.

This method is classified under the asset approach because, in theory, it adds the values of the tangible and intangible assets. Because it involves the capitalization of excess income, some appraisers prefer to call it a hybrid method, and some may even classify it under the income approach.

A schematic diagram of this classification of business valuation approaches and methods is presented as Exhibit 14.1

Schematic Diagram of Business Valuation Approaches and Methods

The “procedure” is a more detailed step used in implementing an appraisal method. For example, as we will see in Chapter 15, there are several accepted procedures to develop discount and capitalization rates within the discounting and capitalizing methods. These procedures are often referred to as methods, and the reader can think of them as methods within methods or the different ways that a method can be carried out.

For example, the discounted cash flow method, or the discounting method, is a major valuation method within the income approach. However, that same term is commonly used to describe a procedure for estimating the discount or capitalization rate to be used within either the discounting or capitalization methods in the income approach.

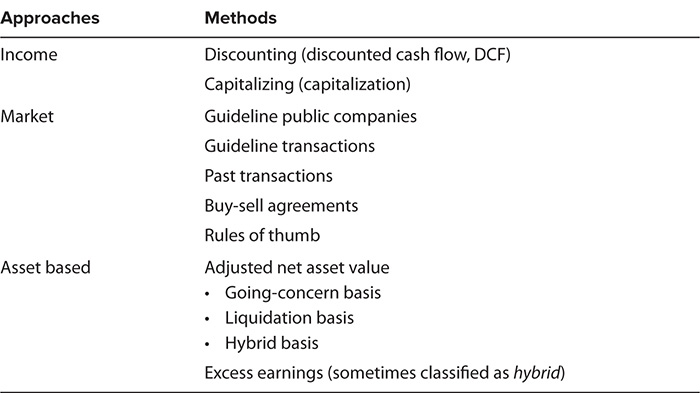

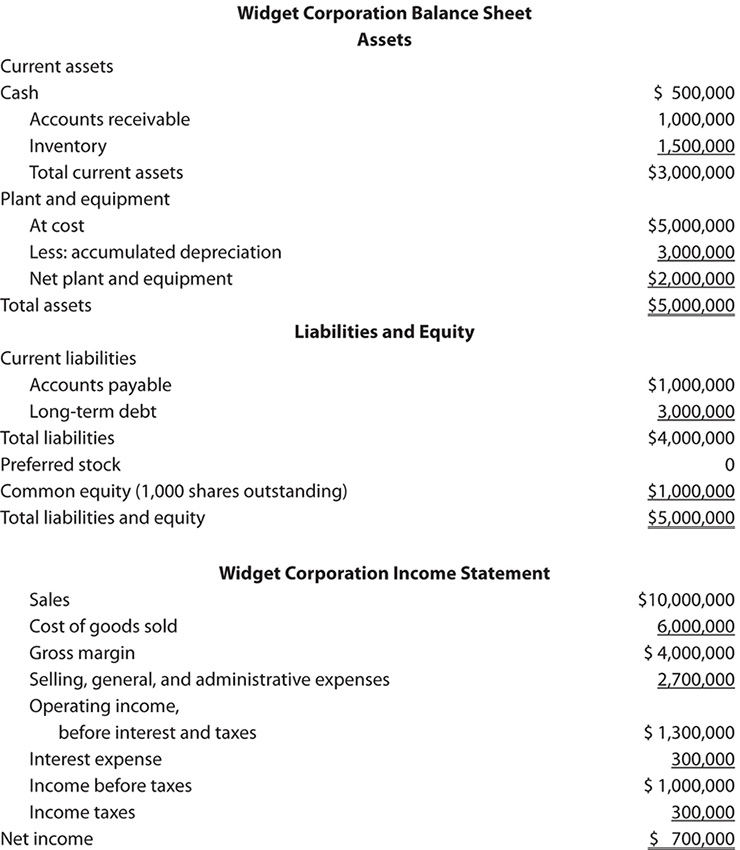

Another important example of different procedures is the choice of either valuing the equity directly or valuing the firm’s total invested capital (common stock [common equity] plus any preferred stock and long-term debt) and then subtracting the debt to arrive at a value for the equity.

This choice of procedures can be available within most of the valuation methods. For example, within the market approach, using either the guideline public company or the guideline transaction method, one could value the equity directly by using a price-to-earnings multiple. Alternatively, one could use the multiple of market value of invested capital to earnings before interest, taxes, and depreciation (MVIC/EBITDA) to estimate the value of the firm’s invested capital, and then subtract the debt from that value to estimate the value of equity.

Some businesses have more than one class of equity, usually preferred equity and common equity. The preferred equity is senior to the common equity, and from a financial analysis point of view, it usually has more of the characteristics of debt than equity. Therefore, the term equity typically is used to mean only the common equity, and the value of preferred equity would be subtracted along with the debt in the invested capital procedures to arrive at the common (or residual) equity value.

Exhibit 14.2 summarizes procedures commonly used within various valuation methods.

Value of Invested Capital and Direct Valuation of Equity Procedures

Unfortunately, the terminology found in the literature of financial theory and corporate finance is fraught with ambiguities, and these carry over into the literature of business appraisal and business appraisal reports. We have addressed the problem in this book by defining each term within the context of the discussion where it is used. To find these definitions, we suggest that readers use the index.

Many appraisal reports contain definitions of terms employed. These definitions should be read carefully because different appraisers may use the same term differently.1 Consequently, the reader of an appraisal may be left to try to figure out the intended meaning, and this becomes even more problematic when interpreting court case decisions.

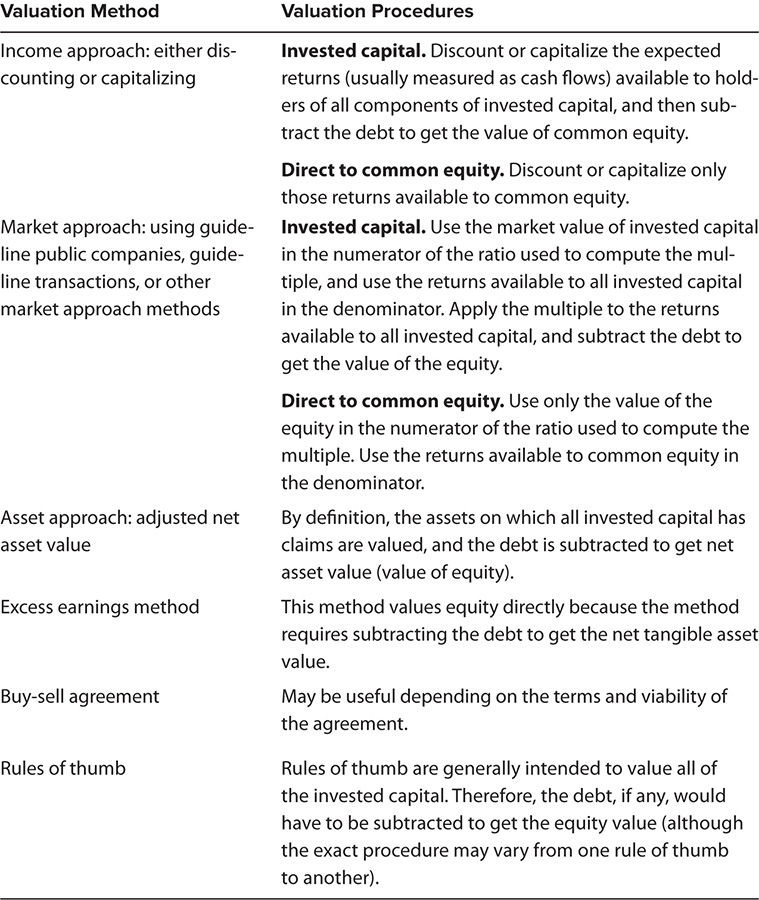

This chapter includes both accounting and financial terms. Many of the numbers represented by the accounting terms can be read directly from financial statements. Numbers representing other accounting terms and numbers for most of the financial terms must be computed. This chapter will define the terms and, where necessary, illustrate how to compute amounts for each. However, this is only the most perfunctory primer; other resources will be necessary for illustrations of more complex financial statements.

With the information shown in Exhibit 14.3, it is possible to extract or compute most of the financial variables that are typically used in the various approaches to business valuation. This chapter necessarily involves numbers and computations. However, it would be impossible to simplify things much more without omitting concepts that one is almost certain to encounter within the scope of reviewing valuation reports. Therefore, we suggest that the reader might want to peruse it fairly quickly the first time through and thereafter use it for reference.

Widget Corporation Financial Data

The two most commonly used financial statements are the balance sheet and the income statement. The balance sheet presents assets, liabilities, and owner’s equity at a point in time, all at book value. Book value generally represents original, historical cost less depreciation and other noncash charges in accordance with accounting principles.

The income statement presents revenues, expenses, and income over a period of time (fiscal period), usually a year. Sometimes (generally if the valuation date is not close to the end of a company’s fiscal year), it may be necessary to use interim financial statements—that is, those prepared as of a time other than the company’s fiscal year-end.

There are three levels of preparation of financial statements, in descending order of their degree of detail (and, usually, their reliability): audited, reviewed, and compiled. Definitions of each are shown in Exhibit 14.4. The appraiser’s report should indicate which level of financial statement preparation was used and also who prepared the statements. This may be different for different dates, and, if so, the correct information should be listed for each date.

Levels of Financial Statement Preparation

• Audited statements. In audited statements, the independent auditor expresses an opinion or, if circumstances require, disclaims an opinion, regarding the fairness with which the financial statements present the financial position, the results of operations, and the changes in financial position, in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles.

• Reviewed statements. The independent accountant expresses limited assurance in reviewed statements that there are no material modifications that should be made to the statements in order for them to be in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles. A review does not provide assurance that the accountant will become aware of all significant matters that would be disclosed in an audit.

• Compiled statements. Finally, the compiled statements are management’s representations presented in the form of financial statements, but the accountant has not undertaken any efforts to express assurance on the statements. Sometimes statements are prepared internally by management without the services of an outside accountant.

The balance of this chapter defines the terms used to describe the most important components of the context of these statements. Analysis of the statements is covered in subsequent chapters.

Please refer to the balance sheet shown in Exhibit 14.3. as the concepts are explained.

Common equity (at book value) is paid in capital plus retained earnings. In Widget Corporation, the common equity is the following:

$1,000,000 from the balance sheet

The invested capital is the equity plus interest-bearing debt. For Widget Corporation, the invested capital at book value is the following:

If the company had preferred stock, that would be shown as a separate item in the capital structure and would be included in the MVIC. (Some define invested capital to include only long-term debt, excluding short-term interest.)

The capital structure is the relative proportions of the various elements of invested capital. In this case, at book value the capital structure is the following:

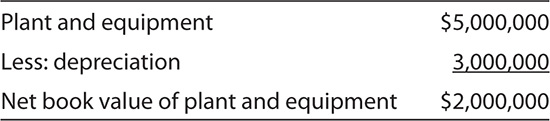

With respect to assets, the book value is the capitalized cost less the accumulated depreciation. For Widget Corporation, for example, the book value is the following:

With respect to the business as a whole, the book value is the difference between the total assets (net of depreciation, depletion, and amortization) and the total liabilities. This is also the book value of the equity. For Widget Corporation, this is as follows:

On a per share basis, the book value is the value of common equity divided by the number of shares outstanding. For Widget Corporation, the book value per share is the following:

The tangible book value reflects only the company’s tangible assets. The total book value reflects both the tangible and intangible assets, such as copyrights, patents, and many other items. If a company buys its intangible assets, those assets generally are on the balance sheet and thus are part of book value.

On the other hand, if the company creates its own intangible assets, those assets usually are expensed and do not appear on the balance sheet. Therefore, for comparative consistency, analysts usually prefer to work with only the tangible book value rather than the total book value. In any case, to completely understand the financial statements being analyzed, the reviewer of the report should know whether or not there are any intangible assets included in the book value if that figure is used for any computations in the valuation report.

The net working capital is the current assets minus the current liabilities. For Widget Corporation, net working capital is the following:

Miscellaneous expense concepts include noncash charges and other items that vary from company to company.

Noncash charges are items that are charged as expenses on the income statement but do not require a cash outlay. Examples would include depreciation, depletion, amortization, and deferred taxes. For Widget Corporation, the only noncash charge is the following:

Depreciation: $250,000 from other financial data

The noncash charges are added back to the net income to arrive at either the gross or net cash flow, and they are added back to the operating income to arrive at the earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA).

The owner’s compensation includes all elements of compensation, including salary, bonuses, retirement benefits, life and health insurance benefits, discretionary expenses, and the value of stock options. For Widget Corporation, the owner’s compensation is the following:

$950,000 from other financial data

One of the most crucial and yet highly ambiguous concepts used in business valuation is that of income, also sometimes referred to as earnings. It is common to see one or the other of these two terms used without further definition. So many different levels of income are used in various business valuation methods and procedures that the term income is virtually meaningless until the level of income intended is clearly specified.

In recent years, the business appraisal profession has embraced the broad term economic income to mean some level of income (any level) that needs further specific definition before it can be used meaningfully in a business valuation method or procedure. All of the following levels of economic income are commonly used in business appraisal practice:

• Sales

• Discretionary earnings

• Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA)

• Earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT)

• Gross cash flow (net income plus noncash charges)

• Debt-free net income (DFNI)

• Debt-free cash flow (DFCF)

• Pretax income

• Net income

• Net earnings

• Net cash flow to invested capital

• Net cash flow to equity

The terms sales and net revenues are generally used interchangeably. For Widget Corporation, the sales amount to the following:

$10,000,000 from the income statement

A multiple of sales is often used in the market approach when valuing invested capital. It is less frequently used (and potentially very misleading) when valuing equity directly because sales are based on the assets supported by the entire capital structure.

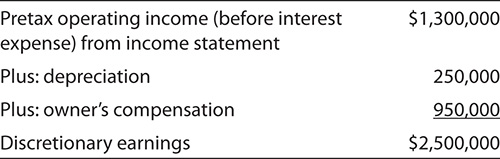

Discretionary earnings are those that may be defined, in certain applications, to reflect the earnings of a business enterprise prior to the following items: income taxes, nonoperating income and expenses, nonrecurring income and expenses, depreciation and amortization, interest expense or income, and owner’s total compensation for those services that could be provided by a sole owner-manager.2 For Widget Corporation, discretionary earnings are the following:

Discretionary earnings are used in the transaction method in the market approach usually only when valuing small companies.

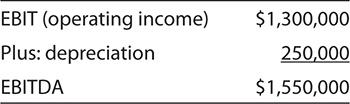

EBITDA is computed as earnings before interest, taxes, and all noncash charges, including depreciation, amortization, depletion, and deferred taxes. Widget Corporation’s EBITDA is the following:

EBITDA is one of the most commonly used variables in the market approach when valuing invested capital.

For Widget Corporation, the EBIT is the following:

$1,300,000 from the income statement

EBIT is one of the most commonly used variables in the market approach when valuing invested capital.

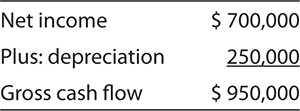

When the term gross cash flow is used, it almost always means gross cash flow to equity, sometimes just called cash flow. It is defined as net income plus noncash charges. For Widget Corporation, the gross cash flow is the following:

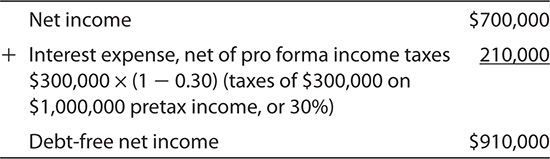

Debt-free net income (DFNI) refers to what the net income would be if there were no debt. It is computed by adding the interest expense, net of the tax effect (income taxes saved because the interest is a tax-deductible expense) to the net income. For Widget Corporation, the DFNI is the following:

The same result is obtained by the tax-affecting EBIT, or the operating income:

When debt-free net income is used, it is in the context of the market approach when valuing invested capital.

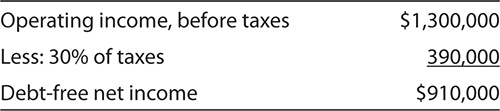

Debt-free cash flow (DFCF) means gross debt-free net cash flow. It is debt-free net income plus noncash charges. For Widget Corporation, the DFCF is the following:

When debt-free cash flow is used, it is in the context of the market approach when valuing invested capital. The “debt-free” measures are used to make companies with significantly different capital structures more comparable to each other. However, since they are artificial in the sense that they create a comparison that doesn’t actually exist, they are losing some favor among analysts.

Pretax income is income after all expenses except income taxes. For Widget Corporation, the pretax income is the following:

$1,000,000 from the income statement

Pretax income is often used in the market approach when valuing equity directly. It is sometimes used in the excess earnings method, sometimes as a proxy for net income in a small company, sole proprietorship, or partnership that does not pay any income taxes.

Net income is income after all expenses, including interest, owner’s compensation, noncash charges, and income taxes. For Widget Corporation, the net income is the following:

$700,000 from the income statement

The net income is used in the market approach when valuing equity directly. It is sometimes used in the excess earnings method as well.

On a per share basis, net income can be stated as either primarily net income per share or diluted net income per share. Primary net income per share is computed on the basis of the number of shares actually outstanding. Diluted net income per share is computed on the assumption of convertible debt being converted to common stock, preferred stock being converted to common stock, and warrants and options to buy stock being exercised. When doing comparative analysis, it is important to be sure that any figures used for comparison are computed on the same basis.

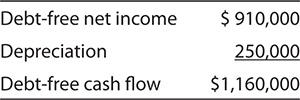

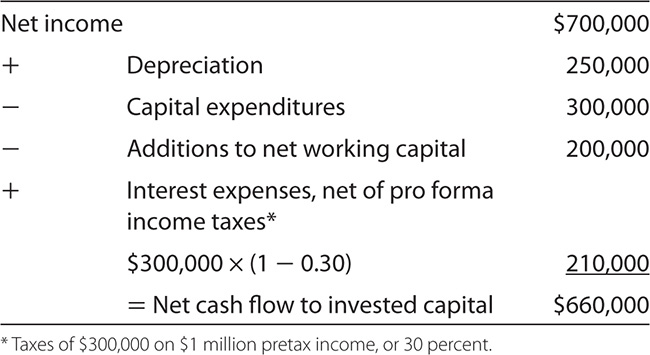

The net cash flow to invested capital is the amount of cash available to distribute to owners of all components of the capital structure (preferred and common equity and interest-bearing debt) after leaving enough for the capital expenditures and working capital necessary to sustain projected operations. The computation is as follows:

For Widget Corporation, the net cash flow to invested capital is the following:

The net cash flow to invested capital is the measure of economic income that tends to be preferred by the professional financial community when using the income approach to value a company’s invested capital. From the valuation of invested capital, the debt and preferred equity are subtracted to get to the value of common equity.

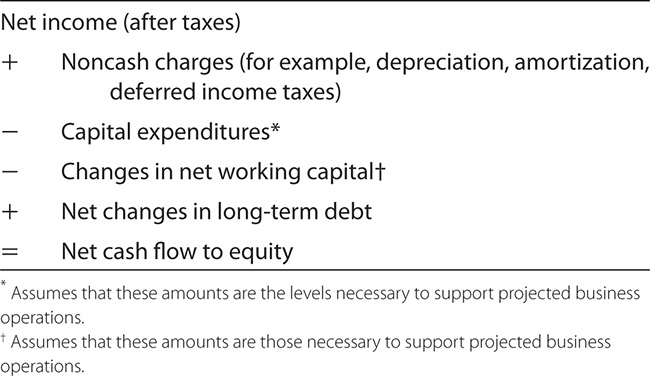

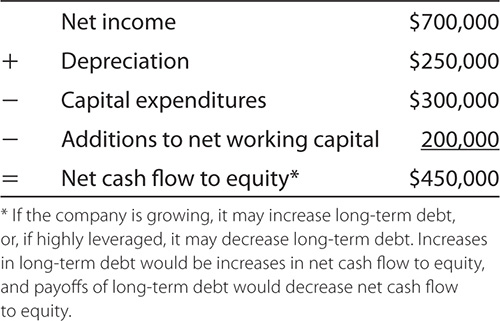

The net cash flow to equity (sometimes called the free cash flow to equity or even the net free cash flow to equity) is the amount of cash available to equity owners to withdraw from or distribute from the business after leaving enough for the capital expenditures and working capital necessary to sustain projected operations. The computation is as follows:

If there are preferred dividends, they must be subtracted. The objective is to estimate net cash flow available to common equity holders. For Widget Corporation, the net cash flow to equity is the following:

The net cash flow to equity is the measure of economic income that tends to be most preferred by the corporate financial community when using the income approach to value equity. Sometimes it is also used as the economic income variable in the excess earnings method.

The capital expenditures are amounts paid for assets expected to have a long-term economic life (usually more than one year), recorded on the balance sheet at the amount paid and usually depreciated (or depleted or amortized) over time as expenses on the income statement and reductions to book value on the balance sheet. For Widget Corporation, the capital expenditures are as follows:

Approximately $300,000 per year from other financial data

The expected capital expenditures must be estimated as a component in computing net cash flow in the income approach since the capital expenditure requirements represent a portion of the gross cash flow that must remain in the business to support the projected operations.

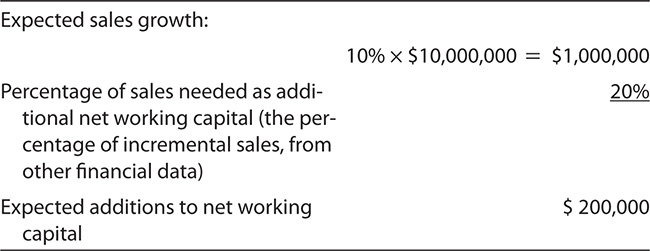

The changes in net working capital are amounts added to or subtracted from the net working capital needed to support the operations of the business:

Changes in net working capital must be estimated as one of the components in computing the net cash flow in the income approach, since it represents an amount of cash flow that must remain in the business to support projected operations

If the company increases long-term debt, the increase is an addition to net cash flow to equity. Conversely, repayments of long-term debt are a deduction when calculating the net cash flow to equity.

Most companies record their accounting on an accrual basis in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). However, some companies, especially smaller ones, prepare their financial statements on a cash basis. Some companies prepare financial statements on an accrual basis and tax returns on a cash basis. Other companies do not prepare financial statements separate from their tax returns, in which case it should be ascertained whether the tax returns are on a cash or accrual basis.

In accrual basis accounting, revenues and expenses are recorded when they are earned or incurred. For example, if a company renders services and bills the customer for later payment, the revenue is shown on the income statement when it is earned, and the account receivable becomes an asset on the balance sheet. This is based on the accounting principle of matching costs with related revenues.

In cash basis accounting, revenues and expenses are recorded when they are received or paid. For example, if a company renders services and bills the customer for later payment, the revenue is shown on the income statement when it is collected, and the account receivable is not shown on the balance sheet at all.

Valuations usually are performed on accrual basis data. For example, once a service has been performed, the revenue and profit are usually considered part of the income stream, and the related receivable is usually considered an asset of the company.

Therefore, if the subject company accounts on a cash basis, the valuation analyst usually adjusts the financial statements from a cash to an accrual basis for the purpose of valuation. Of course, there can be exceptions, such as when a buy-sell agreement requiring valuation using cash basis accounting data is determined to be controlling for the valuation purpose at hand.

All data that have been presented in this chapter have been assumed to be on an accrual basis.

While business valuation approaches and methods are not totally discrete, there is broad consensus on three generally accepted approaches: the income approach, the market approach, and the asset-based approach.

Within each approach, there are two or more generally accepted methods. Within the income approach, the basic methods are discounting and capitalizing. Within the market approach, there is the guideline public company method, the guideline transaction method, the past transactions and/or offers method, buy-sell agreements, and rules of thumb. Within the asset-based approach, there is the adjusted net asset method and the excess earnings method.

Within each method there is a variety of accepted procedures for its implementation. Two of the most important (either of which may be used with most methods) are the invested capital procedure (valuing the entire capital structure and subtracting the senior obligations to arrive at the residual common equity value) and the direct equity valuation procedure (using techniques that value the equity directly).

Business valuation is fraught with ambiguous terminology. This book attempts to define each esoteric term in the context in which it is used. This chapter has provided a rudimentary guide to the terms most often encountered with respect to financial statements as they are used in business valuation. It should make a handy reference for any term with which the reviewer is unfamiliar or for any term about which the reviewer is unsure of the definition commonly used in the context of valuation.