The basic concept of the asset-based approach is that if all the company’s assets and liabilities are revalued to current values, then the difference between the assets and liabilities should equal the value of the equity.

The asset-based approach is generally assumed to produce a control basis value. From this value, if one is valuing a minority interest, it may be appropriate to adjust for factors such as minority interest and lack of marketability. If one is valuing a controlling interest, it may or may not be appropriate to deduct a discount for lack of marketability, although it would be a smaller discount than for a minority interest.

If each asset and liability is individually identified and valued, that method may be described differently using such terms as the net asset value (NAV) method, adjusted net worth method, adjusted book value method, asset buildup method, or asset accumulation method. For the purpose of this chapter, we will refer to the discrete revaluation of all assets as the adjusted net asset value (ANAV) method. The premise of value may be either going concern or liquidation.

In the collective revaluation of assets, the tangible assets, or at least the preponderance of them, are usually adjusted to current values, as discussed in subsequent sections of this chapter. The intangibles are then valued collectively by capitalizing any amount of return that the company achieves over and above a fair return on the tangible assets at their current values.1 This method is called the excess earnings method, which assumes a going-concern premise of value.

In some cases, only a partial revaluation of assets is practical. There are too many variations on this possibility to go into details, and the reviewer is left to make the judgment as to whether the conclusions reached in a particular appraisal are adequately supported.

The five basic steps are as follows:

1. Obtain or develop an accrual basis balance sheet. If the entity does its accounting on a generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) basis, developing this balance sheet requires only those adjustments necessary to conform to GAAP. If the company does its accounting on a cash basis, then adjustments to the accrual basis are necessary.

2. Determine which assets and liabilities on the GAAP basis balance sheet require revaluation.

3. Identify any off–balance sheet actual or contingent assets or liabilities. This could be an unlimited list, but some of the more common items include these:

• Assets fully depreciated but still in service

• Inventory or accounts receivable written off by accounting policy but still salable or collectible

• Intellectual property developed internally and therefore expensed instead of capitalized

• Workforce in place, systems, and similar elements of “going-concern value”

• Goodwill

• Expected proceeds or costs related to existing or potential lawsuits

• Environmental liabilities

• Liability for corporate capital gains taxes on appreciated assets2

4. Value the items identified in steps 2 and 3. This may require appraisals by asset appraisers because appraising real estate and/or machinery and equipment would not be a skill possessed by most business appraisers.

5. Construct a market value–based balance sheet using the adjusted values. The net result of this should be the market value of the equity. In other words, the difference between the market value of the assets and the market value of the liabilities equals the market value of the equity.

Generally speaking, each item will be valued on one of the following four premises of value:

1. Value in continued use, as part of a going concern. This usually means either used-replacement cost, including installation, or replacement cost new less depreciation, amortization, and/or adjustments for obsolescence.

2. Value in place, as part of a mass assemblage of assets. This would generally be used for a manufacturing plant in working order but not currently operating due to market conditions, bankruptcy, or any other reasons.

3. Value in exchange, in an orderly liquidation. This may be appropriate for all assets if an orderly liquidation is contemplated for the entire company. If the company is being valued as a going concern, an orderly liquidation premise may be appropriate for nonoperating or excess assets.

4. Value in exchange, in a forced liquidation. This may be appropriate if, for example, it was assumed that the assets would be sold piecemeal at auction.

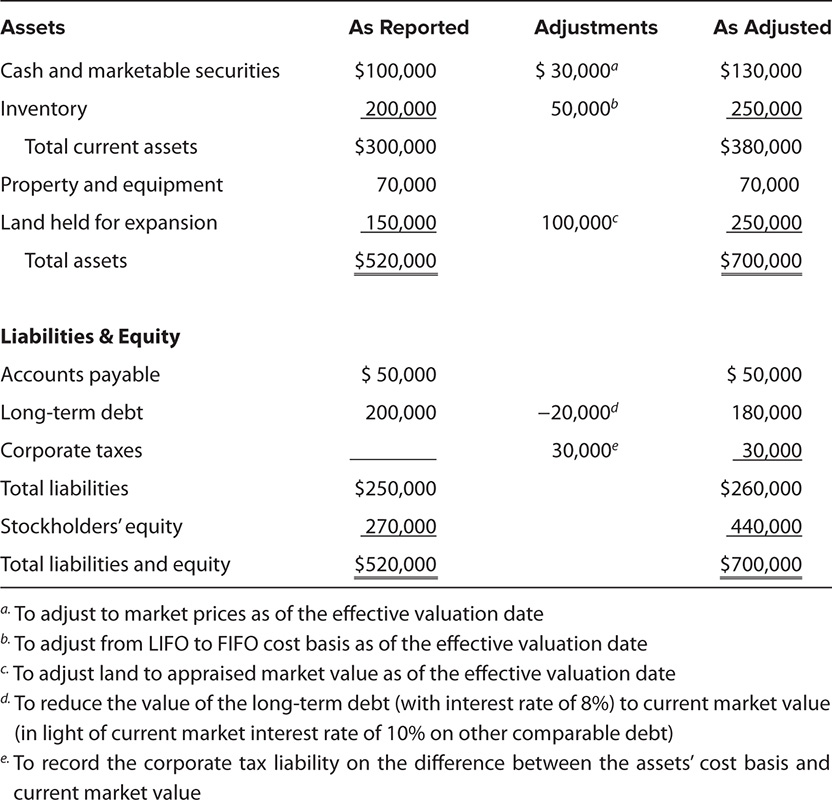

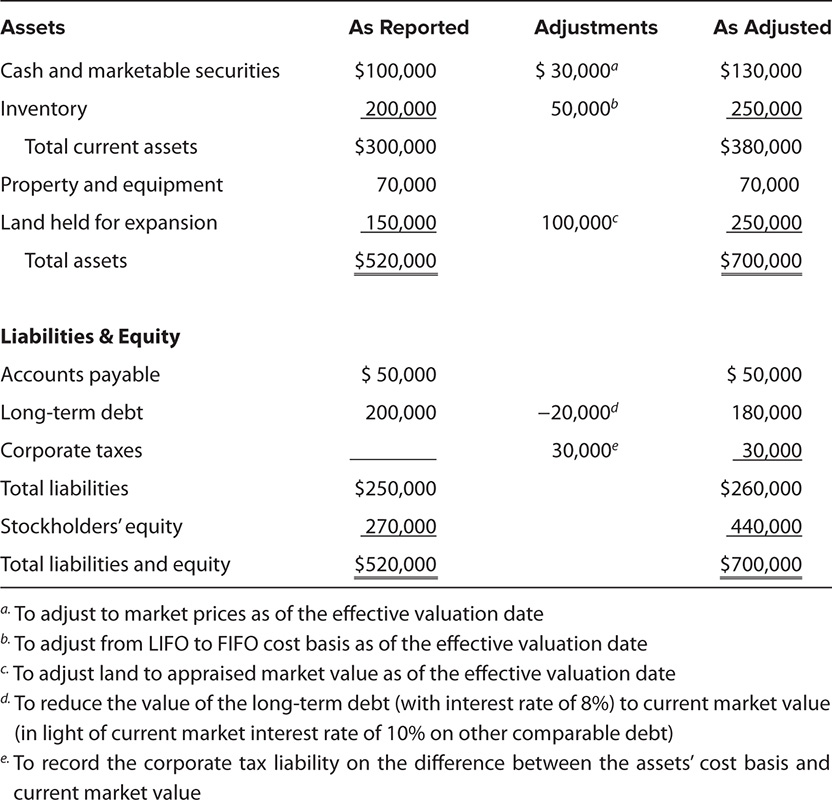

Exhibit 17.1 shows an example of an adjusted balance sheet resulting in an adjusted net asset value. There would be an explanation in either the text or footnotes for each item added to the balance sheet or adjusted from its original balance sheet value.

Alpha Company Adjusted Net Asset Value

Some companies may have two or more operating entities and possibly some nonoperating assets. The stock market tends to value such companies at less than the total of the value of each operating company plus the nonoperating assets.

In considering a possible acquisition of such a company, the acquirer might like to estimate what could be realized by selling each of the operating companies and the nonoperating assets separately. This is called the breakup value.

Studies have shown that conglomerates tend to sell at a discount of about 15 percent from their breakup values. Investors seem to prefer a “pure play” in an industry over a package of dissimilar companies or assets. One variation on the asset approach is to estimate a company’s breakup value.

The net asset value method is not used very often for valuation of operating entities, particularly in minority interest appraisals. The focus for operating entities tends to be more on the income approach, the market approach, or the excess earnings method.

However, there are a number of situations in which the courts do reach a valuation conclusion either entirely or partially on valuation by the asset-based approach. These may include but are not limited to the following:

• Start-up companies

• Holding companies, financial institutions, agricultural businesses, and other asset-intensive businesses

• Marital estate valuations of companies or practices in which all goodwill is personal and the state’s case law does not consider personal goodwill a marital asset

• Companies that may not be financially viable as operating companies

For example, in one marital dissolution, the husband owned two start-up companies. The husband’s lawyer moved to strike the testimony of the wife’s expert, who used the discounted cash flow method even though the projections had been made by the husband. The trial court granted the motion and was upheld on appeal “because the expert’s projections and opinion were overly speculative and by implication, unreliable,” leaving only the testimony on asset value on which the trial court had based its conclusion.3

Fishman, Jay, et al. 2015. “Underlying Assets Methods,” “Net Asset Value Method,” and “Liquidation Value Method.” In PPC’s Guide to Business Valuations. Practitioners Publishing, Ft. Worth, TX pp. 7-1 to 7-18.

Hitchner, James R. 2011. “Asset Approach” (ch. 7). In Financial Valuation: Applications and Models, 3rd ed., Wiley, New York, pp. 309–364.

Pratt, Shannon P., and Alina V. Niculita. 2007. “Asset-Based Approach: Asset Accumulation Method.” In Valuing a Business, 5th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, pp. 349–380.

Trugman, Gary. 2012. “The Asset-Based Approach.” In Understanding Business Valuation, 4th ed., American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, New York, pp. 387–408.