Virtually all states have dissenting stockholder statutes. Dissenters’ rights are triggered by major corporate actions, such as mergers, acquisitions, or liquidations, the criteria for which vary from state to state. Stockholders who dissent may not reverse the corporate action but are entitled to be paid the fair value of the shares immediately before the action has been put into effect, excluding any anticipatory appreciation or depreciation.

A growing number of states also have minority oppression statutes, many of which are based on the Model Business Corporation Act (MBCA), as revised.1 Significantly, Delaware, considered a bellwether of corporate law, does not have a minority oppression statute, and the Delaware Supreme Court has refused to impose a remedy for minority shareholder oppression absent a pronouncement from the state’s legislature.2 Nonetheless, it is clear that a majority of states provide some form of relief for oppressed minority shareholders.3

Some states require that the collective minority seeking oppression relief own some minimum percentage of the total stock; others have no such requirement. Criteria required to trigger a finding of oppression or irreconcilable differences vary. In most states, oppressed owners may seek dissolution of the entity. Most states also provide for alternative remedies, particularly a compulsory buyout of the minority by the majority of the company at fair value.4

One line of cases requires a finding of wrongdoing by the controlling shareholder, such as self-dealing or repudiation of going-in corporate governance arrangements.5 In such jurisdictions, the judicial scrutiny ordinarily takes the doctrinal form of an inquiry into whether the majority shareholder has breached a duty of “utmost good faith and loyalty” that is owed to the minority investor. Another line of cases defines oppression with reference to what a court determines to be the reasonable expectations of the minority shareholders. This “reasonable expectations test” is normally applicable only to founding shareholders and is based on expectations at formation.6 Some states, such as Illinois, define oppression as “heavy-handed and overbearing or arbitrary conduct.”7 Especially in states that do not have an oppression dissolution statute, some courts have imposed a fiduciary duty between close corporation shareholders, and they have permitted a minority shareholder to bring a direct cause of action for breach of this duty. In the seminal decision of Donahue v. Rodd Electrotype Co., the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court adopted such a standard:

We hold that stockholders in the close corporation owe one another substantially the same fiduciary duty in the operation of the enterprise that partners owe to one another. In our previous decisions, we have defined the standard of duty owed by partners to one another as the “utmost good faith and loyalty.” Stockholders in close corporations must discharge their management and stockholder responsibilities in conformity with this strict good faith standard. They may not act out of avarice, expediency or self-interest in derogation of their duty of loyalty to the other stockholders and to the corporation.8

Other courts have imposed a similar duty.9 It is arguable that such a duty should be imposed in limited liability companies as well.10

Shareholder, limited liability company member, and partner suits involving valuation of interests arise in a variety of situations. The most common are these:

• Dissenting stockholder actions

• Suits for dissolution of a corporation, limited liability company, or partnership, usually based on a claim of minority oppression

• Breach of fiduciary duty (often coupled with minority oppression)

Although shareholder actions in all these categories are on the rise throughout the country, several states do not have precedential case law on many valuation issues. In deciding on issues, it is very common for states to quote case law from several different states.

Stockholder appraisal rights are defined by state statute. The state statutes also designate the standard of value to be applied. A recent review of the state statutes relating to dissenting stockholder rights indicates that all states except California designate fair value or fair cash value as the standard of value (California’s statute specifies fair market value). Most states have modeled their dissenting stockholder statutes after the Model Business Corporation Act. This act was revised in 1984 and became known as the Revised Model Business Corporation Act (RMBCA), which has had revisions through 2002. Until 1999, the RMBCA defined fair value as follows:

The value of the shares immediately before the effectuation of the corporate action to which the shareholder objects, excluding any appreciation or depreciations in anticipation of the corporate action unless exclusion would be inequitable.

In 1999 the definition changed to:

“Fair value” means the value of the corporation’s shares determined:

(i) immediately before the effectuation of the corporate action to which the shareholder objects;

(ii) using customary and current valuation concepts and techniques generally employed for similar businesses in the context of the transaction requiring appraisal; and

(iii) without discounting for lack of marketability or minority status except, if appropriate, for amendments to the articles pursuant to section 13.02(a)(5).11

The majority of states12 use the pre-1999 definition, and only a handful have adopted the 1999 version. A minority of states uses the pre-1999 definition without the “unless exclusion would be inequitable” phrase, and some states omit this phrase but, in addition, add a clause that states that all relevant factors should be considered in determining value. Florida and Illinois use a hybrid of the pre-1999 and 1999 definitions.13

According to the official comment of the RMBCA, the definition of fair value leaves to the parties (and, ultimately, to the courts) the details by which fair value is to be determined within the broad outlines of the definition. As a result, interpretations of fair value vary considerably from state to state.

A typical and frequently quoted interpretation of the philosophy of fair value in a dissenting stockholder situation is the following:

Fair value, in an appraisal context, measures “that which has been taken from [the shareholder], viz., his proportionate interest in a going concern.” (Source: Tri-Continental Corp. v. Battye, Del. Supr. 74 A.2d 71, 72 [1950].)14

There is far more shareholder dispute litigation in Delaware than in any other state, primarily because so many corporations are incorporated in Delaware. This is particularly true of dissenting stockholder litigation. One of the results is that Delaware dissenting stockholder cases are quoted more than cases from any other state.

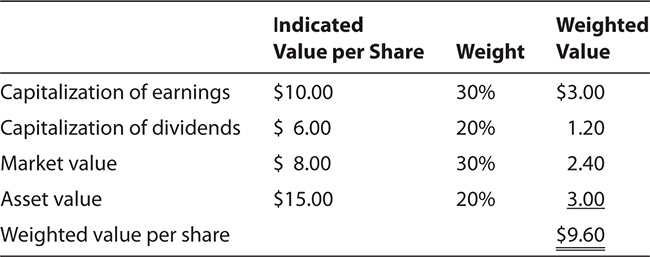

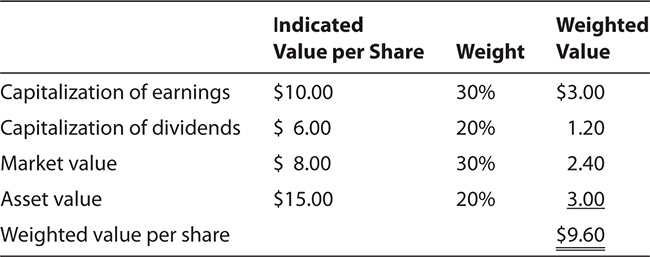

Before 1983, dissenting stockholder cases primarily used the Delaware Block Method. This method develops values in each of three categories: investment value, market value, and asset value. Mathematical weightings are then assigned to the indications of value from each of the three approaches (although the weight to one, or even two in extreme cases, could be zero), and the resulting weighted average is the concluded value.

The definitions of investment value and market value in this context are a little different from those discussed in the three basic approaches to value.

Investment value in the context of the Delaware Block Method means value based on expected earnings and/or dividends. It is akin to the value based on the income approach in the three basic approaches to value. It may be arrived at by discounted cash flow, capitalization of earnings, or capitalization of dividends. In this sense it mixes the traditional income approach and market approach in that it may derive capitalization rates by methods under either.

Market value, on the other hand, has historically been based on prior transactions in the subject company’s securities. This contrasts with the traditional appraisal concept of market value as discussed in Chapter 14, where multiples of both income statement and balance sheet parameters based on comparable transactions are used.

The summary of a typical Delaware Block Method appraisal might look something like the following:

However, a landmark case in 1983 said that the traditional factors considered under the Delaware Block Rule alone were not necessarily sufficient; instead, all relevant factors must be considered. In that particular case, the court specifically made the point that projections of future earnings were available and should be considered. The court also made the point that a determination of fair value “must include proof of value by any techniques or methods which are generally considered acceptable in the financial community.”15

The interpretation of fair value is a subject of continued debate and is difficult to generalize. However, most states have embraced the notion that “all relevant factors should be considered.”

Courts have treated investment value (defined in this context as value based on earning capacity) as the most important of the three elements. In fact, in one case the Delaware Court of Chancery stated that the discounted cash flow (DCF) model is “increasingly the model of choice for valuations in this court.”16 However, as noted earlier, one landmark case pointed out that all relevant factors must be considered,17 and the Delaware Court of Chancery has rejected the DCF method where it finds that the projections or data underpinning the DCF analysis are inadequate.18 Some courts have also indicated that a fair market value analysis may be a “relevant factor” that should be considered in determining fair value.19

Courts tend to rely heavily on expert reports and testimony in resolving fair value cases. Even in circumstances with diametrically opposed professional perspectives on the value of the entity in question, the courts typically accept certain portions of each expert’s valuation and fashion their own conclusion.

The question frequently arises whether a “relevant factor” is what a company might be sold for if it were put “in play.” The most likely buyer of many companies is another industry participant, who may be expected to pay more because of operational synergies or competitive advantages obtainable from the purchase. One difficulty is that any attempt to apply this standard requires some assumptions regarding the prospective buyer and is not limited to the operating characteristics of the company on a stand-alone basis.

Strategic buyer valuation also would seem to be in conflict with the language contained in most dissenters’ rights statutes that appreciation in anticipation of the corporate action is not to be included. While the Delaware courts appear to have rejected this standard,20 language in opinions from other states may be construed to permit consideration of strategic buyer values.21 (In Canada, courts routinely include strategic value as an element of fair value in dissenting stockholder cases.) Some commentators also contend that not all synergies should be disregarded since only those synergies not available to a particular buyer may be indicative of investment value.22

The largest single issue in most shareholder and partner valuation disputes is whether discounts and/or premiums are applicable, and, if so, what should be the magnitude of such discounts and/or premiums. The most common issues involve minority discounts or control premiums and discounts for lack of marketability. Positions on these issues vary from state to state, and sometimes state case precedents change, so it is necessary to be aware of the latest precedential case law.

For example, not very many states have adopted the RMBCA, but even some of those that have not have refused minority and marketability discounts, citing the revision. Furthermore, case precedent often is different for dissenting stockholder actions than it is for dissolution actions.

States often differ in their acceptance or rejection of discounting for lack of marketability and lack of control.

Some states leave the question of applicability of both minority and marketability discounts to the court’s or a jury’s discretion.23 For example, the Illinois Court of Appeals in Jahn v. Kinderman said with regard to such discounts that “the application of a discount was a matter for the discretion of the trial court.”24 These courts are reluctant to set a bright rule in the event that circumstances or justice require the application of a discount.

For example, in Advanced Communication Design, Inc. v. Follett,25 the court indicated that it would only be fair and equitable to apply a marketability discount to the value of the company because there was no possibility that the company could achieve the liquidity necessary to compensate the departing shareholder. This was viewed as an extraordinary circumstance warranting the application of the discount. The American Law Institute (ALI) recognizes such extraordinary circumstances in the definition of fair value that it includes in its Principles of Corporate Governance.26 It defines fair value thus:

The value of the eligible holder’s proportionate interest in the corporation, without any discount for minority status or, absent extraordinary circumstances, lack of marketability.

Other states also find the applicability of minority and marketability discounts to be a discretionary matter, but they require the court to consider whether extraordinary circumstances warrant the application of a discount for lack of marketability.27 For example, the primary issue in two cases, decided the same day by the New Jersey Supreme Court,28 was whether a marketability discount should be applied in determining the fair value to be paid in shareholder suits.

In Wheaton, a statutory appraisal action, the court stated the following:

The history and policy behind dissenters’ right and appraisal statutes lead us to conclude that marketability discounts generally should not be applied when determining the “fair value” of dissenters’ shares in a statutory appraisal action. Of course, there may be situations where equity compels another result. Those situations are best resolved by resort to the “extraordinary circumstances” exception in 2 ALI Principles, 7.22(a).

In Balsamides, in an oppressed shareholder action, the court stated the following:

To secure “fair value” for Perle’s stock, a marketability discount should be applied. To do otherwise would be unfair, particularly since Perle was the oppressor and Balsamides was the oppressed shareholder.

Delaware has consistently rejected the application of discounts. In Cavalier Oil v. Harnett,29 the Delaware Supreme Court indicated that the objective of the appraisal outlined by the state’s appraisal statute was to value the corporation itself rather than value a specific fraction of shares in the hands of one shareholder, and therefore, no shareholder-level discounts should be applied.

Of the states that have declared themselves on the issue of discounts in dissenters’ rights actions, several follow the lead of Delaware and reject discounts for either minority interest or lack of marketability, either by statute30 and/or case law.31 For example, the Iowa Supreme Court affirmed a lower court valuation that rejected a discount for lack of marketability.32 Another example is Pueblo Bancorporation v. Lindoe, Inc.,33 in which a divided Colorado Supreme Court affirmed a decision denying a lack of marketability discount when determining fair value under Colorado’s dissenters’ rights statute. The court noted that the trial court must first determine the value of the corporation as a going concern and the pro rata value of each outstanding share, and it said that discounts should not be applied except under extraordinary circumstances.

In Brown v. Arp and Hammond Hardware Co.,34 the Wyoming Supreme Court, finding that the clear majority of courts have held that minority discounts do not apply when determining fair value in the appraisal context, ruled that it would join the majority and not permit such discounts.

The Kansas Supreme Court overruled a previous decision that allowed a minority discount in an action for appraisal: Moore v. New Ammest, Inc.35 The court stated the following:

In answering the certified question before us, we hold that minority and marketability discounts should not be applied when the fractional share resulted from a reverse stock split intended to eliminate a minority shareholder’s interest in the corporation.36

We believe it is important to recognize that the applicability of this decision is limited to the narrow circumstances of the question put to the court: “when the fractional share resulted from a reverse stock split intended to eliminate the shareholder’s interest in the corporation.” There are many other actions where dissenters’ rights are triggered even though the stockholders are not forced to be cashed out, a fact set that would seem to be very distinguishable from this case.

In Oregon, a marketability discount may be applied in a dissenters’ case, but a minority discount may not (Columbia Management Co. v. Wyss, 94 Ore. App. 195, 765 P.2d 207 [1988]). However, in a minority oppression case (Hayes v. Omstead & Associates, Inc., 21 P.3d 178 [Or. Ct. App. 2001]), neither discount is to be applied because the minority shareholder is entitled to recover his pro rata interest without regard to discounts applicable in other settings.

It is important to keep up on the current case law because states sometimes change their positions or take different positions from one case to another depending on the facts and circumstances of each. For example, a 1998 Montana Supreme Court dissenting stockholder case reversed a lower court decision that had accepted a 30 percent minority interest discount. Under the Montana Business Corporation Act, the Montana Supreme Court prohibited the consideration of a minority interest discount when establishing fair value.37 This was in spite of the fact that a 1996 Montana Supreme Court minority oppression case allowed a 25 percent minority discount, stating that the stockholder “has not demonstrated to the satisfaction of this court that ‘fair value’ necessarily excluded an application of a minority discount.”38

Some states permit the application of shareholder-level discounts in determining fair value (or “fair cash value”) in shareholder dissent and oppression cases. Some permit only the lack of marketability discount,39 some permit only the lack of control discount,40and some permit both.41

One of the most commonly cited cases regarding the use of a control premium is the Delaware Supreme Court case of Rapid-American Corp. v. Harris.42 That case involved a statutory appraisal action contesting a merger. The state supreme court held that the trial court was required to add a control premium to the publicly traded equity value of a corporation’s shares for each of the corporation’s operating subsidiaries.

Hintmann v. Weber43 is a case decided by the Delaware Court of Chancery after Rapid-American. The corporation was a holding company whose primary asset was 100 percent of the Fred Weber corporation’s class A common stock, which represented approximately 90 percent of Fred Weber’s value. Based on Rapid-American, the court decided that a control premium should be added to the value of Fred Weber’s as a subsidiary of Weber Industries, Inc. The mean premium for publicly held companies in the 12 months ended June 30, 1992, was approximately 45 percent, and the median premium was about 55 percent. Because a portion of those premiums reflected post-merger values expected from synergies, the appraiser arbitrarily adjusted the premium down to 20 percent, which the court accepted.

Gilbert Matthews, currently an investment broker with Sutter Securities in San Francisco, has commented that, although this decision is well reasoned in accordance with case law, there are several errors of logic with respect to the control premium:

1. Discounted cash flow (DCF) value should represent the full value of the future cash flows of the business. Excluding synergies, a company cannot be worth a premium over the value of its future cash flows. Thus, it is improper and illogical to add a control premium to a DCF valuation.

2. The average premium in other transactions is not a relevant standard. It is biased upward by the fact that it includes purchases of companies that are undervalued in the market but excludes those that are overpriced.

3. Even if the average premium were relevant, it is calculated in relation to unaffected market value. Market price usually includes a minority discount, particularly for acquisition targets. The court applies it to a value that, in a Delaware appraisal, specifically excludes any minority discount.

4. The value of Weber Industries to any third party would not have been affected by its corporate structure. If Weber Industries had not been a holding company but had owned Fred Weber, Inc. as a division, Rapid-American would not have applied and there would have been no control premium added. This elevates form over substance.44

In a subsequent Delaware case, Borruso v. Communications Telesystems International,45 the issue before the Court of Chancery was not whether a control premium should be applied but when it should be applied during the calculations. The court accepted one expert’s methodology on this issue over the other expert’s:

I am persuaded that Petitioners’ approach to the control premium is wrong. The observation that the comparable company method of analysis produces a minority equity value does not require that I change the methodology of that analysis. Rather, it requires only that I adjust the result derived from it to eliminate the implicit minority discount. Instead of adjusting the result, Huck undertook to alter, in a significant way, the methodology itself. Doing so, in my view, introduced an analytical distortion that, in this case, significantly overstates the value of the WXL equity. Neither Petitioners nor Huck has supplied authority in the valuation literature justifying this change in the accepted methodology. Because Huck’s methodology is inconsistent with the methodology followed in Harris v. Rapid-American Corp., 1992 Del. Ch. LEXIS 75, *9, Del. Ch., C.A. No. 6462, Chandler, V.C. (April 1, 1992), and because it is otherwise hard to square with the comparable company method, I will not adopt it.

In Doft & Co. v. Travelocity.com, Inc.,46 the court, sua sponte, added a 30 percent control premium, saying, “The equity valuation produced in a comparable company analysis does not accurately reflect the intrinsic worth of a corporation on a going concern basis. Therefore, the Court, in appraising the fair value of the equity, ‘must correct this minority trading discount by adding back a premium designed to correct it.’”

In a Maine dissenters’ rights action involving a small, closely held business, the court permitted a control premium adjustment, concluding that the control premium could properly be used as an upward adjustment of the value of the subject company’s shares when compared to similar companies in the industry.47 The Iowa Supreme Court has also held that in an appraisal action, a control premium may be considered in determining fair value if it is supported by the evidence.48

Another frequently encountered issue is whether the value of a company with low-basis assets should be discounted due to the risk of tax liability if some or all of these assets are later sold. The U.S. Tax Court has reversed its prior position and approved a discount for such built-in capital gains.49

The Washington Court of Appeals in Matthew G. Norton Co. v. Smyth50 rejected a bright-line rule rejecting a discount for trapped-in capital gains, reasoning that while discounts for such gains are not generally appropriate in dissenters’ rights appraisal cases where no liquidation of the corporation is contemplated, such discounts might be appropriate at the corporate level if the business of the company is such that appreciated property is scheduled to be sold in the foreseeable future, in the normal course of business.

The Wyoming Supreme Court ruled that under the state’s appraisal statute (pre-1999 RMBCA version), absent clear evidence that the company was undergoing liquidation, a discount for trapped-in capital gains would violate the purpose of the statute: to compensate dissenting shareholders for the “fair value” of their shares in a going concern.51

The Delaware courts employ the concept of “entire fairness.” This means procedural fairness as well as substantive fairness or fair value. If the transaction fails in terms of procedural fairness (fair dealing), the relief to the plaintiffs may go beyond just the fair value as adjudicated pursuant to dissenting stockholder statutes.

Procedural fairness is generally measured by two criteria: (1) independence and (2) competence and thoroughness.

Substantive fairness (fair price) also has two elements: (1) absolute fairness and (2) relative fairness.

Violations of the above criteria caused Delaware Vice Chancellor Jacobs to deny a motion for summary judgment to dismiss a class-action suit that allowed plaintiffs only the appraisal remedy. Among the facts cited by Judge Jacobs were these:

• The company obtained no fairness opinion at the time of the cash-out merger.

• The board did not establish an independent committee to safeguard the interests of the minority stockholders.

• There had been a series of private purchases at prices higher than the cash-out price, a fact that was undisclosed.

Judge Jacobs concluded that, since there was evidence that the entire fairness test was not met, “the Court must reject the defendants’ argument that appraisal is the exclusive remedy.”52

In another case, the Delaware Supreme Court found that “the Special Committee [of the board] chose as its financial advisor a bank which had lucrative past dealings with … related companies.” Furthermore, the special committee’s legal advisor was previously retained by two related companies. The court concluded that the special committee did not act in an independent and informed manner. Therefore, the case was remanded for a new fairness determination, with the burden of proof shifted to the defendants.53

A classic example of lack of fairness is found in Ryan v. Tad’s Enterprises. First, the controlling stockholders arranged an asset sale of the corporation’s major holding, a six-store New York restaurant chain, with employment and noncompete contracts of $1 million each. It then did a squeeze-out merger. One lawyer acted as a board member, represented the corporation in the transactions, and represented the controlling stockholders personally in negotiating their employment and noncompete agreements. The board did not retain any unaffiliated law firm, financial advisor, or other independent representative to represent or negotiate the merger on behalf of Tad’s minority shareholders.

The opinion states, “Normally this court will defer to a decision involving the business judgment of a corporation’s directors. … However, that presumption vanishes in cases where the minority shareholders are compelled to forfeit their shares in return for a value that is determined as a result of a bargaining process in which the controlling shareholder is in a position to influence both bargaining parties.”54 The dissenters ultimately were awarded $23.86 per share versus the $13.36 amount originally offered.

Another Delaware case finding a lack of entire fairness was M.G. Bancorporation v. Le Beau,55 which found that the directors’ failure to establish an independent committee of directors to represent the minority shareholders’ interests, while on its own did not constitute evidence of unfair dealing, when combined with other pleaded facts could support a claim of unfair dealing. The court also found that the difference between the stock’s $85 per share fair value and the $41 per share merger price, combined with the other pleaded unfairness claims, created an inference that the merger was the product of unfair dealing.

Lack of entire fairness usually occurs when control stockholders cause transactions that benefit them at the expense of other stockholders without independent oversight. The most common scenario is a transaction without an independent appraisal, often coupled with not having an independent committee of the board of directors to evaluate the transaction from the perspective of fairness to minority stockholders. Directors or controlling shareholders who stand on both sides of a transaction have the burden of establishing the transaction’s entire fairness.56

In Gesoff v. IIC Industries, Inc.,57 the class of minority shareholders argued that a going-private merger, intended by a foreign parent corporation to remove the minority shareholders of its U.S. subsidiary, was a product of unfair dealing, producing an unfair price for the subsidiary. Notwithstanding the defendants’ argument that the merger was fair because any irregularities in the merger dealings did not affect the fairness of the merger price, the Delaware Court of Chancery found that the merger process was marked with grave examples of unfairness and led to a plainly unfair price for the going-private transaction. Consequently, the court awarded damages to the class and to those stockholders seeking appraisal based on the court’s determination of fair value at the time of the merger—a figure significantly in excess of the consideration offered in the going-private transaction. In reaching its conclusion, the court determined that the process established by the defendants unilaterally imposed on the minority a price of the parent’s own choosing, established a deceptive negotiation between the parties and left the minority’s putative special committee almost entirely powerless against its parent.

One thing that is clear is that virtually no court equates fair value with fair market value. In a New York case, the expert retained by the company based his valuation on a fair market value. The court stated, “The Standard on which [the expert’s] valuation was based was Market value. … The statutory standard is much broader. … The Court may give no weight [emphasis added] to market value if the facts of the case so require.”

The court also decided that the company’s appraiser “was not independent in its evaluation and was unduly controlled and influenced by the petitioner to arrive at a low value.”58 Ultimately, the court rejected any minority and marketability discounts and awarded the dissenter $99 per share, as compared with the $32 per share originally offered.

In another example, the Colorado Supreme Court in Pueblo Bancorporation v. Lindoe, Inc., said, “We are convinced that ‘fair value’ does not mean ‘fair market value.’”59 The New Jersey Supreme Court has expressed a similar sentiment,60 as has a majority of courts in other jurisdictions.61

Other courts, however, have indicated that use of a fair market value analysis may inform the fair value standard of value where such an analysis is a “relevant factor,” and that although the market value may be accorded little or no weight by a factfinder, the fair market value analysis may not be excluded and must be permitted at trial.62 The Eleventh Circuit, while acknowledging that “fair value” and “fair market value” are not synonymous, has also indicated that they are not “mutually exclusive,” so that when “potentially distorting corporate actions” such as a merger or sale are not at issue, fair market value may serve as an estimate of fair value.63

When states lack precedential case law on an issue, they often look to other states for guidance. Thus, appraisers and lawyers often research cases in other states, especially states with similar statutory wording.

For example, in Utah’s case of first impression under its dissenting stockholder statute, the appellate court cited case law from other states with similar statutes, including Iowa, Maryland, Maine, Delaware, and Massachusetts. Among its conclusions, it stated: “We agree with the courts cited above that a dissenting stockholder disclaims both the burden and the benefit of the disfavored corporate action. … Any effect of the sale must be excluded. … Fair value is not measured by any unique benefits that will accrue to the acquiring corporation.”64

Before determining that “fair value” does not mean “fair market value,” the Colorado Supreme Court conducted an extensive review of the law in other jurisdictions on this issue.65

Apparent inconsistencies are common in the field of fair value cases, often as a result of less than fully informed expert testimony. In a North Dakota case, it was alleged (and unrebutted) that an appraisal followed Delaware case law. However, it was apparent after reading what was done that the appraisal did not interpret the appraisal methodology as it is actually applied in Delaware.66

Courts usually hold assiduously to requirements for timeliness of filings and other procedural matters in dissenting stockholder actions. If the dissent is not filed within the statutory period, dissenters’ rights are almost always considered waived.

When dissenters’ rights actions are filed, most state statutes then require the corporation to commence a proceeding to determine the fair value of the shares within 60 days after receiving the demand. If it doesn’t commence the proceeding within the 60 days, it must pay the dissenters the amount demanded.

In a Georgia case, for example (where the statute was based on the Model Business Corporations Act), the trial court awarded the dissenters the amount demanded because the corporation failed to initiate the valuation proceeding within the statutory period. The corporation appealed, and the trial court’s judgment was affirmed.67

Brewer, Wilbur, Jr. “Minority Shareholder Rights.” A 17-page paper on the rights of minority shareholders in closely held corporations, available on www.BVLibrary.com.

Cory, Jacques. 2004. Business Ethics: The Ethical Revolution of Minority Shareholders. New York: Springer.

Eggart, James. 2002. “Replacing the Sword with a Scalpel: The Case for a Bright-Line Rule Disallowing Application of Lack of Marketability Discounts in Shareholder Oppression Cases.” Arizona Law Review, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 213–246.

Emory, John D., Jr. 1996. “The Role of Discounts in Determining ‘Fair Value’ Under Wisconsin’s Dissenters’ Rights Statutes: The Case for Discounts.” Wisconsin Law Review, 1995, no. 5 (March), pp. 1155–75. Although specifically oriented to Wisconsin, the article references statutes and cases throughout the United States.

Fishman, Jay E., Shannon P. Pratt, et al. 2009. “Fair Value under Shareholder Dissent and Minority Oppression Actions” (ch. 15). In PPC’s Guide to Business Valuations, 19th ed. Fort Worth, TX: Practitioners Publishing.

Fishman, Jay, et al. 2008. “Fair Value Under Shareholder Dissent and Minority Oppression Actions.” In PPC’s Guide to Business Valuations. Fort Worth, TX: Practitioners Publishing, pp. 15-1 to 15-10.

Jacobs, Jack B. 1999. “Adjudicating Statutory Appraisal and Breach of Fiduciary Duty Valuations in the Delaware Court of Chancery,” interview with Shannon Pratt. Judges & Lawyers Business Valuation Update, September, pp. 1, 3–4.

Malick, S. A. 2000. Oppression of and Relief for Minority Shareholders: Cases and Commentaries. Golden Books Centre, Selangor, Malaysia.

Mantese, Gerard V., and Ian Williamson. 2005. “Minority Shareholder Oppression: From Estes to Franchino.” Michigan Bar Journal, August, pp. 16–20.

Minnesota Institute of Legal Education, Minneapolis. “Minority Shareholder Disputes.” Several hundred pages of conference papers in three-ring binder. Although primarily oriented to Minnesota, the papers reflect national research on the issues.

Moll, Douglas K. 2005. “Minority Oppression and the Limited Liability Company: Learning (or Not) from Close Corporation History.” Wake Forest Law Review, vol. 40, p. 883.

O’Neal, F. Hodge, and Robert B. Thompson. 1998. O’Neal’s Oppression of Minority Shareholders: Protecting Minority Rights in Squeeze-Outs, and Other Intracorporate Conflicts, 2nd ed. St. Paul, MN: West Group.

Pratt, Shannon. 1999. “Shareholder Suit Valuation Criteria Vary from State to State.” Valuation Strategies, January/February, pp. 12–15.

_____. 2003. “Shareholder Buyouts and Disputes.” In Business Valuation Body of Knowledge, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley, pp. 321–324.

Shartsis, Arthur, Jr. 1999. “Dissolution Actions Yield Less Than Fair Market Enterprise Value.” Judges & Lawyers Business Valuation Update, January, p. 5.