Commercial appraisals include a wide range of income-producing properties, such as apartment complexes, retail strip centers, shopping centers, office buildings, medical buildings, and hotels and motels. The income approach to value is the predominant and normally the most reliable approach to use for appraising income-producing commercial properties.

The income approach is based on the principle of anticipation that can be defined as follows:

The perception that value is created by the expectation of benefits to be derived in the future.1

This concept of anticipation might also be understood in considering what buyers and investors normally seek in purchasing income property: the highest profit for their investment. Consequently, an investor might be willing to pay a certain amount for a property based on the present worth of what the buyer perceives will be future benefits. To determine this, the buyer will most likely use the most basic income approach, which is called direct capitalization.

Direct capitalization is a tool investors use to determine how much income a property will make in a year, and an understanding of this is necessary to properly review a commercial appraisal. It is defined by The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal as follows:

1. A method used to convert an estimate of a single year’s income expectancy into an indication of value in one direct step, either by dividing the income estimate by an appropriate rate or by multiplying the income estimate by an appropriate factor.

2. A capitalization technique that employs capitalization rates and multipliers extracted from sales. Only the first year’s income is considered. Yield and value change are implied, but not identified.2

It may also be defined, in its most basic sense, as a method to convert the income of a property into an indication of value.

Another way of looking at direct capitalization is with the simple concept that if a buyer has a choice between two assets that are alike, the buyer will pay more for the one that makes more money. As previously stated, the premise that investors will pay a certain amount of money for an investment based on the expected profits they hope to receive from that investment is the foregone conclusion. And when comparing investment opportunities, direct capitalization is the standard method used by investors and appraisers to determine which investment yields the most profit.

Just as a person chooses the best interest rate from a variety of banks offering savings accounts, the real estate investor considers the rate of return offered by income-producing properties by calculating the capitalization rate. However, with savings accounts that are FDIC insured funds, the saver will probably have to consider only the rate, whereas the real estate investor will have other considerations besides the capitalization rate. Moreover, the way the rate is computed—that is the underlying information on which the rate is based, is an important aspect of determining the validity of the rate and, hence, the value of the property.

The primary advantage, then, of the direct capitalization income approach is that it approximates the thinking of the typical investor. The approach measures income for only one year, but the investor will often extrapolate that to consider what the income might become in future years. Direct capitalization is a starting point for many investors because the first question they may have is, “What is the cap (capitalization) rate?”

The disadvantages of the approach stem from the fact that there are many aspects to consider, including how the income data is analyzed and interpreted by those who compute the rate. It is also subject to manipulation, and a slight change in data may effect a major change in the value conclusion.

The reliability of the rate also diminishes when the method used to compute the rate does not come from the market. In other words, appraisers typically look at other sales to determine the capitalization rate to use, and that method (the market extraction method) is the only one that many reviewers would consider reliable because it is based on the actions of buyers and sellers in the marketplace. It is also the only one discussed in detail in this book.

Other methods are considered to be more susceptible to manipulation and subjectivity. It is highly recommended that if another method is encountered in an appraisal, the reviewer should question why that method was used rather than the market extraction method. The explanation of how the other methods are used is beyond the scope of this book, but the following is a brief explanation of some of them.

In the buildup method (sometimes called the built-up method), a rate is determined by analyzing components of the rate. The two basic components are the recapture rate and the interest rate. This method is based on the concept that the investor for the property expects to get a return of the investment—that is, the sales price at the end of the term of ownership, which is also called capital recapture. The investor also expects a return on the investment, which is the investor’s profit on the money used to buy the property, and it is referred to as the return on rate, as well as some other names.

In the band of investment method, the appraiser considers the financial components or bands of debt and equity capital required to support the investment. It takes into account the rate required by the lender and the rate necessary for the equity investor’s desired pretax flow.

In the yield capitalization method, the real estate investment return is separated into two components. One is the income flow for a specified number of years, and the other is a capital change (gain or loss) that results at the end of the multiyear investment period from an assumption that the property will be sold then. It is computed on a cash account basis from the investor’s point of view.

There are also other methods such as the annuity method, building residual technique, and land residual technique. However, to reiterate, none of these methods are considered as reliable as the market extraction method, and it is advised that the reviewer consider the use of these methods questionable for properties for which comparable sales are available from which rates can be extracted.

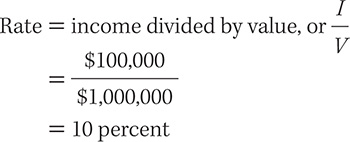

The formula for direct capitalization is often referred to as the income, rate, value (IRV) formula because it is calculated as follows, depending on what is sought:

To Find the Capitalization Rate

To Find the Income

Income = rate times value, or I = R × V

To Find the Value

A simple example would be an investment that costs $1 million and has an income of $100,000 a year:

The income used in this formula is what is called the net operating income (NOI). However, there are several steps needed to get to the net operating income. To begin the process, the appraiser must start with the property’s actual gross income, which might be defined as the property’s total income from all sources for one year. Using the example of an apartment complex, this income would include rent, as well as income from other sources such as laundry services, vending machines, parking fees, and interest earned on security deposits held in the bank. The rents for the apartments should be confirmed by ledgers that show what the current rents are. In some cases, if it is possible, tenants might be interviewed to confirm the ledger amounts. If the complex is large, then a sampling of tenants might be sufficient if there is a lack of other verifiable evidence. If there is a question about the veracity of the stated income, the reviewer might want to ask for further information.

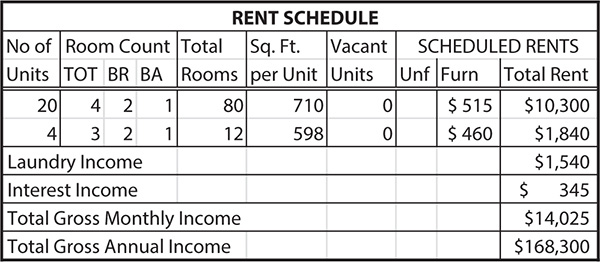

An example might be a 24-unit apartment complex. The complex has 20 units that are two-bedroom apartments and 4 that are one-bedroom apartments. The actual gross income (also called contract rent) for the property might look as it is shown in Exhibit 5.1.

Rent Schedule

This spreadsheet shows the actual gross income for one year, but it is not the income the appraiser will use to determine the value. The appraiser will examine the rents for the units to determine if they are at market or not. Normally, they will be at market or below market, and most likely the latter because landlords are rarely able to keep increasing rent right up to the market rent. Moreover, leases are often signed that limit the rent until the lease expires, although some rental agreements include escalators, which build in increases at certain times during the lease. If the rent is above market, it could be the result of escalators that are higher than market. Otherwise, if the rents are above market, the veracity of the reported rents might come into question.

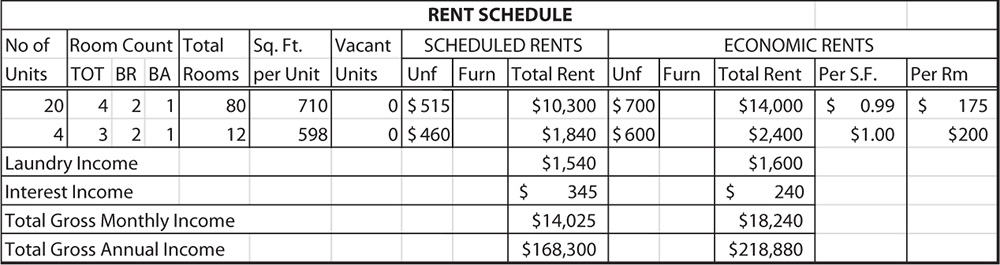

The appraiser will seek to determine what is called the potential gross income (PGI), which will include estimates for economic rent or market rent. These two terms refer to the amount of rent the apartments could rent for if the rents were current. A savvy investor will consider what the maximum rents might be and may plan to raise them after the purchases, providing there are no leases that prevent an increase. In the spreadsheet in Exhibit 5.2, the economic rent has been estimated.

Rent Schedule with Economic Rent

In addition to the economic rent as listed in Exhibit 5.2, there is also a price per square foot and per room for the apartments. It appears from this information that the scheduled rents are significantly lower than the economic rent. Because there is such a difference, it would be important to know the reason why, which may be stated in the appraisal. It may be that the landlord has kept rents low because he or she has good tenants and the landlord does not want them to have a reason to vacate, which is often the case. Nevertheless, whatever the reason is, it should be understood by the reviewer because it will have a major effect on the final value conclusion.

The appraisal will most likely include a rent survey that has a compilation of rents for similar properties. The appraiser will probably quote the source for this survey, and it might be a secondhand survey. The term secondhand, in this case, means a survey that was conducted by a third party, such as a local real estate company. This type of information may look official, but it is actually much poorer evidence of the market rent than a firsthand survey conducted directly by the appraiser. One of the reasons is that rent surveys are often more general surveys and may include rents from properties that are not similar to the subject property. They also normally include very large apartment complexes because real estate companies can more easily track rents with these types of properties.

In our example, the subject property is a small complex, and rents should be derived from similar properties. Small apartment complexes may have fewer amenities than large ones, but they may also be preferred because many renters do not like large complexes. Therefore, one cannot conclude that rents would be higher or lower between the two types of properties. However, one can conclude that there is enough dissimilarity that the rent survey may not be accurate when rents from large complexes are applied to a smaller complex, and vice versa.

There is a relatively easy way for the reviewer to check the rent survey for accuracy. Even if the reviewer is in a different part of the country, local rents can be found using the Internet to search the area where the property is located. A search on Craigslist or a similar website that advertises rentals can give the reviewer a good idea of what apartments are renting for that are similar to the subject. The appraiser may also have used this source, but the reviewer can verify the accuracy of the appraiser’s research with a minimal investment of time.

Leases are another issue to consider. The appraiser may not be aware of leases that exist on the property and may be using a potential gross income that is not reachable for several years due to lease commitments. This is often more of an issue with retail and other commercial properties than it is with apartments because businesses often sign long-term leases. If the appraiser discusses the leases in the report, the reviewer may want to confirm what is said or request a copy of the leases if that is possible. The reviewer should not assume that the appraiser’s information about the leases is accurate unless the leases are included in the report or the source is given with contact information. Mistakes in this area are often made, and sometimes erroneous information is given to the appraiser. A brief discussion with the owner or manager might have been the only source for the information, and if it was erroneous, the value conclusion can be skewed.

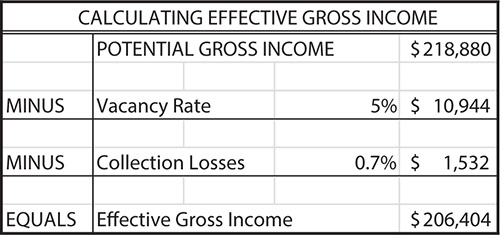

Once the potential gross income is determined, the next step for the appraiser is to adjust it to get the effective gross income (EGI). Exhibit 5.3 gives the formula and calculation to compute the effective gross income for our example.

Calculating the Effective Gross Income

As demonstrated in Exhibit 5.3, the effective gross income is calculated by subtracting the vacancy rate and collection losses from the potential gross income. To get an accurate estimate for these two numbers, it is important to have historical rental data on the subject property. The appraiser may have a survey showing that the vacancy rate is 5 percent, but that number assumes certain things that may not apply to the subject property. For instance, if the subject property is located adjacent to a busy freeway and there is a lot of traffic noise, the vacancy for the subject property may be much higher than 5 percent. There could be other issues that might diminish or increase the vacancy factor that are specific to the subject property but not common to most properties.

If a survey provided by others is used, the appraiser should explain the source and how it was conducted. Often surveys track only certain properties. If the subject is an office building, a national real estate company may track several office buildings in the subject’s city. If it is an apartment complex, there may be several complexes that are tracked. Understanding the source of the survey will help the reviewer determine how similar, and hence applicable, the other properties are to the subject property.

The other item to subtract is collection losses. In most appraisals, the vacancy percentage and the collection losses will be combined into one percentage. Often 5 percent is the lowest one might see, but there are cases in which the vacancy factor can be lower.

With some retail spaces, generally in shopping malls, tenants might be allowed to stay for free. They pay no rent because the mall does not want empty spaces that would cause more tenants to leave, which in turn would cause fewer people to shop there. In such cases, the free rentals must be considered as vacant. Moreover, with such a property, the future viability of its continuing to function is problematic and should be considered by the appraiser.

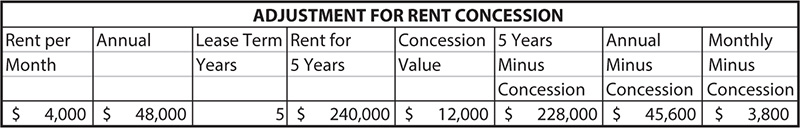

The free rent should not be confused with concessions, which are given to renters of apartments or commercial properties. Concessions such as one month’s free rent might be used to entice a new tenant, but they do not necessarily mean the complex is in financial trouble. With commercial retail and office space, there are often concessions that might include a remodel of the space based on a fairly long term lease. In such cases, the actual rent can be calculated by dividing the cost of the concession or free rent by the term of the lease, as shown in Exhibit 5.4.

Adjustment for Rent Concession

As seen in the spreadsheet, whether it is actual rent that is not charged or some modification of the space, the value of the concession is $12,000. Over the five-year lease period, the rent would then be $3,800 per month rather than $4,000 per month. Appraisals may show concessions in different ways, but if concessions are the norm for renting the spaces, they should be considered in any projection of potential rents.

The income information that is used for the appraisal may also be sullied by the fact that the owner may not have audited financial information. Another problem could be that the owner may produce income tax returns, but he or she may have erroneously deducted some expenses for the property as a way of reducing the income taxes. In the first situation, the profits for property may be exaggerated, but in the second situation the actual expenses would be less than what was reported.

In other words, the source of the income information is always in question when the income approach is used; therefore, the reviewer of the appraisal should consider its fallibility. In the appraisal, the appraiser has probably made estimates for expenses in addition to considering the actual reported expenses, and those estimates should be considered and compared to typical percentages for similar properties. For instance, it may be that expenses generally run around 40 percent for most apartment complexes similar to the subject property, but the subject is reporting expenses of only 30 percent. If the appraiser is also using 30 percent, and that figure is not supported by expense ratios for other properties listed in the report, the report should state the reason why.

The Internet can also be a good source for expense ratios as can reports compiled by major real estate brokerages, which may often be obtained for free by asking. These reports are usually composed of averages and are not specific to a particular property, but if the reviewer can get this data, it will provide a benchmark for comparison against the expense ratio in the appraisal.

The operating statement is an important part of the income approach. It should be modified for different types of accounting and for personal or nontypical expenses.

The operating statement will supply most of the information to the appraiser. It can be prepared in one of two ways. The first method is the cash basis, in which cash income is recorded when it is received, and expenses are recorded when they are actually paid. The other method is the accrual basis, in which income is reported in a certain period even if it has not been actually received in that period, and expenses are reported in the same period regardless of whether they were actually paid in that period. It is often the case that businesses use the accrual basis, whereas individuals use the cash basis.

The appraiser has to know which method was used to modify the statement for the appraisal. Consequently, the operating statement will be modified for the type of accounting used and for the items that are not applicable to the appraisal. It will also be modified to take out expenses that would not be applicable to the typical buyer.

When buyers consider purchasing income-producing properties, they normally also look at costs and benefits that relate to their personal situation, but these items would not be part of the appraisal. Some of these are expenses that would be used for accounting purposes, and the appraiser should take these out of the operating statement in reconstructing it for appraisal purposes. The following is a list of such items.

The appraisal is performed without considering what the financing expenses or the interest rate might be. (There is an exception to this, which would be the mortgage equity capitalization method, but it is not considered a particularly reliable method, and it is beyond the scope of this book.) However, in using comparable sales, financing is considered by the appraiser because certain types of favorable financing may influence the sale price of the property. This may seem like a contradiction, but it is not: essentially the appraiser considers that the financing for the subject property will be typical in competing with other properties that have sold, so it is only the anomalous sale that would require an adjustment. As previously stated, adjustments are always made to the comparable sales and not the subject property.

An example would be an owner-financed sale with an interest rate 2 percentage points below the current lending rate from lending institutions. In such a case, the lower rate would require an adjustment to the selling price (reflected in a financing adjustment made to the comparable sales), which would effectively raise the price of the sold property as a counterbalance to the extremely favorable financing.

Buyers will calculate the depreciation for the property, and that is part of their financial planning. One buyer might consider a cost segregation study (a breakdown of items in the building that can be depreciated more quickly under IRS rules) to increase depreciation, whereas another will take the standard depreciation for the whole building. In any event, the personal income tax situation of the buyer will unquestionably influence the buyer’s behavior, but this relates to the buyer and not to the property, so it would not be considered in the valuation.

Management expenses are expenses that the appraiser will consider, but with smaller properties or properties with triple net leases (leases are explained in Chapter 7), the buyer may decide to self-manage. The appraiser will use typical management expenses, so if the owner self-manages, there would be a savings to the owner but not one that would be reflected in the appraisal.

The exception to this might be for very small income properties. Sometimes an appraiser will leave out a management fee if owner management is considered the norm. Since this will affect the final value, the appraiser should state how this factor correlates to the compilation of sales from which the capitalization rate was estimated. The appraiser should have clear evidence that the comparable sales did not include a deduction for management fees. Management fees are normally in the range of 3 to 10 percent, depending on the duties required.

This is also called a replacement allowance, and it is defined in The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal as follows:

Replacement allowance: An allowance that provides for the periodic replacement of building components that wear out more rapidly than the building itself and must be replaced during the building’s economic life.3

The idea behind this is that there should be an adjustment for money needed for improvements such as new carpeting, roofing, flooring, appliances, hot water heaters, HVAC items, parking lot asphalt, and painting. Instead of subtracting the whole amount for these items, the appraiser estimates what will be needed for them and amortizes the expense over the years of the life of the item. For example:

There has been some debate about using reserves for several reasons because of the way it affects the capitalization rate. When appraisers get rates from other properties, there is no certainty as to whether the rate was computed using reserves, and if it was, the question arises as to how the estimate was made. In an apartment complex, was there a reserve for each appliance, and if so, what life was assigned to them? Was it 3 years for a dishwasher or 8 years? Was it 20 years for the roof or 30 years? Was resurfacing of the parking lot considered or not? Was there a reserve for the sidewalks, and how many years were estimated for tearing them out and installing new concrete? It is easy to see why it is important in reading an appraisal to understand how these calculations may affect the value conclusion.

Exhibit 5.5 is a full list of expenses that one might find in an appraisal for an apartment complex. It comes from a commonly used appraisal form: Freddie Mac Form 71A.4

List of Expenses for an Appraisal of an Apartment Complex