Generally only two approaches are used to value machinery and equipment: the cost approach and the sales comparison approach. The income approach might be used to value a machine based on its production and efficiency, but it is so rarely used that this book will concentrate only on the first two approaches. But before they are examined, the reviewer needs to gain an understanding of the information the appraiser should have to utilize the approaches.

When appraisers begin a machinery and equipment assignment, the asset list is normally their starting point. Companies maintain asset lists for a variety of reasons, including inventory records, property tax records, and income tax records. Some companies keep very good records, while others do not, and equipment that is retired or newly added may not appear on the asset list. Therefore, the accuracy of the list can be an issue in the valuation of a company, particularly if it’s a large company with a lot of machinery and equipment. The asset list may be called the fixed asset list, which generally means that items consumed in a year or less are not on the list.

Although it may seem simplistic, knowing what is actually at the industrial site where the equipment is supposed to be is one aspect of any machinery and equipment appraisal that should be considered when the appraisal is analyzed. Nevertheless, it is often the case that the majority of the value will reside in certain major pieces of equipment, and if those pieces are inventoried, the absence of less expensive equipment may not have a substantial effect on the value.

The appraiser might perform a sample inventory on the equipment and compare it to the asset list to determine the accuracy of the list. This exercise may begin with a check of 5 or 10 percent of the assets, which are chosen randomly. If these show the asset list to be accurate, the appraiser may stop there, but if the asset listing is unreliable at this point, the appraiser may take a larger percentage and, in some cases, may perform a detailed audit. Normally every piece of equipment will not be audited, unless the company is very small, because the value of spending time looking for smaller assets that have depreciated in value is questionable.

The appraiser may decide on a cutoff point in value for the assets that he or she will definitely examine, and this will vary according to the size of the company and the value of the assets. For example, only items over $100,000 in value may be physically examined for one company, whereas only items over $500,000 in value may be examined for another company.

Companies generally carry a book value, which is the value of their assets after depreciation for accounting purposes. Property is booked at a certain value according to the depreciated value, which is not the fair market value, and it is important to understand the difference. Under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), property owned by corporations is either capitalized or expensed. If the item is capitalized, it will be depreciated for income tax purposes over a certain number of years. If it is expensed, it will be depreciated fully in one year.

For an example of capitalized equipment, consider the following example. The purchase price of a machine (normally including installation, transportation, and interest to finance it) is $1 million. It would typically be capitalized, and the company accountant would depreciate it according to IRS guidelines, generally for the maximum allowable depreciation. (Note: There are exceptions. For some calendar years, the IRS may allow accelerated depreciation.)

The IRS has industry classifications, and the allowed amount of depreciation correlates to the classification. With the $1 million example, if the equipment had an IRS designated life of seven years, the depreciation for each year would be as follows based on straight-line depreciation, which means each year gets the same amount of depreciation:

$1,000,000 / 7 = $142,857 per year (rounded)

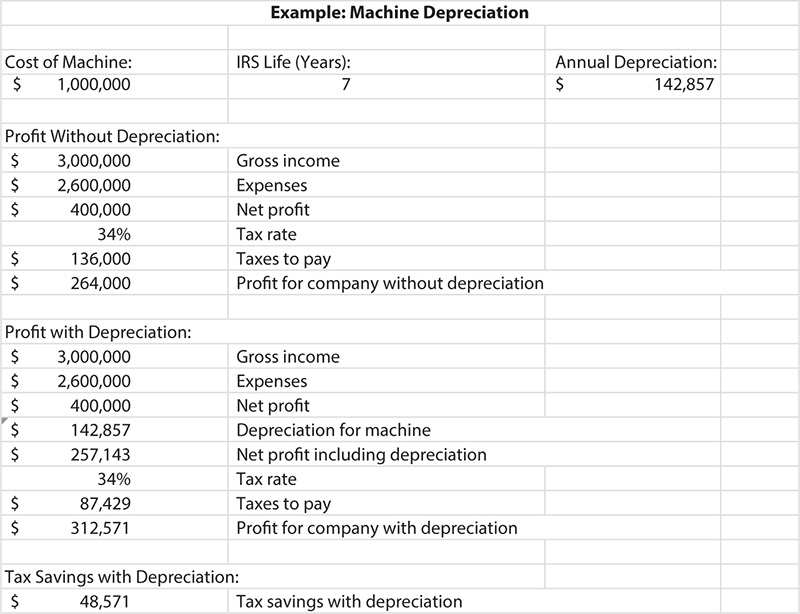

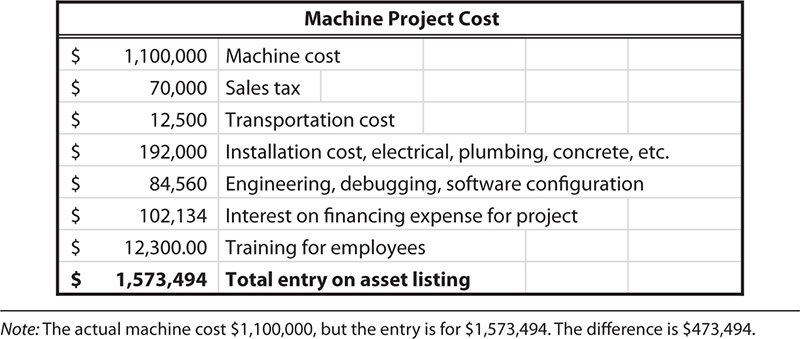

The company is allowed by the IRS to deduct this amount each year for seven years, which reduces its taxes and results in higher profits. For a simplified example, assume the company made $3 million in gross income, and after expenses were paid, the company made a net profit of $400,000 before income taxes were paid. The spreadsheet in Exhibit 9.1 shows the difference in profits with and without the tax savings.

Machine Depreciation Example

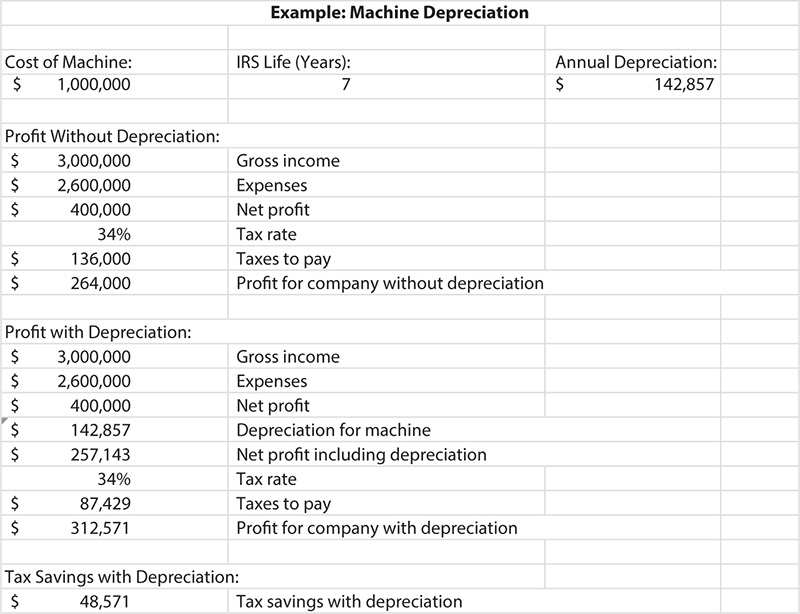

This also means that the value of the machine, as it is computed for book value, follows the seven-year cycle, as seen in Exhibit 9.2. In reality, this machine may be worth $300,000 in year 7, or $400,000 or $100,000 or even $50,000, but according to the IRS depreciation rules, it is depreciated to zero value in the seventh year.

Seven-Year Straight-Line Depreciation

Although this chapter is about machinery and equipment, accounting methods for buildings will be briefly discussed since they are similar. Depreciation for buildings is also determined by what the IRS allows, and for commercial and industrial buildings the current “life” for buildings in these categories is 39 years. Land is not depreciated but instead is segregated from the building based on its market value (often accountants will use the property tax assessment estimate for the land value). For example, if the building was purchased for $3 million, and the land is worth $300,000, the depreciation would be calculated as follows:

$3,000,000 − $300,000 = $2,700,000

$2,700,000 / 39 years = $69,231

Therefore, the company can deduct a depreciation expense of $69,231 per year, which will result in tax savings that increase profits for the company.

The depreciation for the machine may or may not have equaled the true yearly value diminution—if it happened to equal it, then that would be a coincidence. The machine may actually last for 10 or 15 years instead of 7 years. Or the machine may have become obsolete in 3 years and is no longer very useful to the company. In the latter case, there are ways to accelerate depreciation if it can be proven to the IRS.

With the building, depending on the economy of the area and the type of building it is, the value may have actually increased instead of decreased, and the chances that the value will correlate to the 39-year depreciation table is even less likely than with the machine.

As demonstrated thus far, the book value does not correlate to the fair market value, liquidation value, or any other value that the appraiser will be estimating. Depreciation used in accounting does not measure the fair market value of the equipment being depreciated. It is only an allocation of the annual depreciation for tax purposes. Therefore, the net book value of the plant, or of the machinery and equipment of the plant, is the sum of depreciated original costs, which is an artificial value based on IRS depreciation tables and not an appraised value.

If the equipment is not capitalized by the company accountant, it will be expensed. When it is expensed for IRS purposes, it is depreciated in one year. Another way to say this is that it is “written off” in the same year it was purchased. Generally, a company will have a policy that sets a threshold at which the property it owns is either capitalized or expensed. For instance, a company may decide to expense every item under $2,500 and capitalize items over that amount.

Consequently, by examining the list, the appraiser should have noticed that nothing over $2,500 is on it, indicating that the list is a fixed asset list only and does not have expensed items on it. If that is the case, the appraiser should have asked the company for a complete listing of equipment, which would include the expensed items, because they are still counted in valuing the assets of the company. In analyzing the appraisal, the reviewer could also make the same determination if the asset list is part of the appraisal or if it can be requested. Adding expensed items that still have value may not amount to a lot, but it will make the appraisal more accurate.

It should also be noted that with some asset-based lending, the appraiser, at the direction of the lender, will list only those items over a certain threshold amount, regardless of accounting policy, because the potential lender cannot realistically use smaller assets for lien collateral.

It is helpful to know if the appraiser has had the asset list reconciled to the general ledger. This is something that the appraiser cannot do—it must be done by the company’s accountant. The reconciliation to the general ledger accounts for all the expenditures and validates the list as accurate in the company’s accounting records.

Double entries and other mistakes are normally discovered in the process, as well as other accounting errors. Whether or not this has been done may not be stated in the appraisal, but depending on the level of review of the appraisal and the authority of the reviewer, it is an important step in confirming the accuracy of the asset list.

Normally, the appraiser, upon receiving the asset list, will sort out the assets according to classifications. The company will likely have assigned cost center numbers and/or classification numbers that will help in gathering like-kind equipment into categories. The appraiser will need to do this to accurately trend the property, about which more will be discussed later in this chapter. The following is a typical classification table:

1. Buildings

a. Production buildings

b. Office buildings

c. Small support structures

2. Land

a. Utilized land

b. Excess land buildable

c. Excess land not buildable such as wetlands

3. Yard improvements

a. Fencing

b. Concrete

c. Asphalt

d. Guard shack or other small buildings

e. Detention ponds

f. Bone yard

g. Storage areas—gases, chemicals, and so on

h. Electrical equipment area

i. Miscellaneous

4. Mainline production machinery—that is, mainline machinery used to produce goods. This category could include computer numerical control (CNC) machines, plastic injection mold machines, paper machines, baking ovens, wafer steppers, or other equipment depending on the industry.

5. General support equipment (nonintegrated). This category would include machines that are peripheral but necessary to the production process, such as brake presses, cutting machines, and polishing machines.

6. Process support equipment (integrated). This category includes support equipment that is integrated into the infrastructure. Semiconductor fabrication plants, for example, have a lot of this type of equipment because their buildings are constructed for the processes that are utilized.

a. Piping for chemicals and gases

b. Electrical power equipment beyond what is necessary for the building to operate; includes motor control centers (MCCs)

c. Special foundations to support machinery and equipment but not necessary for the building

7. Computers and related equipment

a. Personal

b. Mainframe

c. Network

d. Printers

e. Software (not taxable in some jurisdictions)

8. Furniture, fixtures, and office equipment

a. Desks

b. Chairs

c. File cabinets

d. Office machines

e. Facsimile machines

f. Intercoms

9. Research and development (R&D) and testing

a. Testing equipment

b. Laboratory equipment

a. Short-life tools

b. Larger mobile tools

c. Molds, jigs, dies, patterns, templates

11. Transport equipment (rolling stock)

a. Licensed vehicles

b. Unlicensed vehicles

c. Forklifts

12. Noninventory supplies

a. Supplies used for operations but not part of the final product

b. Fuels—gasoline, diesel fuel, oil, and so on

c. Cleaning agents

d. Spare parts

e. Hardware

f. Electrical components to maintain machinery and equipment

13. Pollution control equipment

a. May include equipment that burns gaseous pollutants before release

b. May include equipment that neutralizes acids or other dangerous chemicals

c. May include equipment that cleanses process water before discharging it

d. Equipment may have shortened life if new laws change to require stricter environmental controls

These supplies are used to maintain the machinery and equipment and the facility. They are not inventory—that is, they do not become the product or part of the product. Rather, they are used to service and support the facility and the machines in the facility. They include such things as fuels for forklifts, office supplies, spare parts for equipment, hardware to maintain the building, fluids for the machines, and other things of this sort.

These items should be considered by the appraiser if the valuation is for all the machinery and equipment in the plant, unless the client has stated that they should be excluded. If the appraisal is, for instance, for a company buyout and these items are not noted or valued in the report, this oversight might constitute an error of incompleteness in the appraisal. In such a case, the reviewer might want to read the instructions for the appraiser, which is generally in a letter in the appraisal, to see what the appraiser was contracted to value.

Inventory is generally not part of a machinery and equipment appraisal, but it can be, depending on what the appraiser is asked to value. If it is part of the valuation, there are several important aspects to consider. First, is the inventory constantly changing? This is normally the case in a going concern, and the effective date of the appraisal would be of paramount importance if that were the case. If the plant is shut down, the value of any unsold product may be questionable because selling it would be difficult without an active system of salespeople, distributors, and retailers.

The appraiser may be experienced with machinery and equipment, but valuing inventory is a complex task that requires specific knowledge of the marketing part of a business. Therefore, any value put on unsold inventory needs to be scrutinized carefully, and the type of value (fair market, liquidation) also needs to be explained in the report. Inventory that retails for a certain price for a going concern may sell for a small fraction of that amount when a company closes down.

This is equipment that is integrated into the building to support the larger machinery and equipment. It is often built into the infrastructure if the building was constructed for a specific use, or it may have been added to an existing building. It typically includes special electrical wiring, piping for gases, water, and other liquids, concrete supports, drains and gutters for the equipment, and other items necessary to install and run machines. Semiconductor manufacturing is an example of an industrial sector that normally designs buildings with process support infrastructure. Buildings for this industry normally have a lower level that contains the gases, chemicals, and electrical power that are fed to the next level for use in production.

The appraiser needs to separate these items from the shell of the buildings to value them. An aid to this would be a cost segregation study, if one is available. A cost segregation study is a listing of items that according to the IRS depreciate more quickly than the building shell. These items must be segregated from the shell and categorized according to their respective depreciation schedule for the IRS to allow the faster depreciation. If this study does not already exist, the appraiser may segregate these items to value them for an appraisal of the facility.

In reviewing an appraisal of this type of industrial facility, particularly if it is not functioning, it is important to understand that the process support items may be rendered valueless if the building is sold for another use. The reason is that it is improbable that a different type of manufacturing would require the same infrastructure. Moreover, in the example of a semiconductor building, rarely do two companies use the same setup of process support equipment. This means that the value of what exists in a shutdown facility, even if it is sold to a company with similar manufacturing, may be a fraction of the original cost.

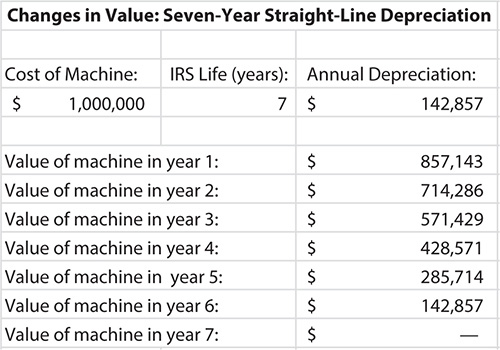

A question often arises as to what costs are included in entries on the asset list that the appraiser has. This question can also have significance in the review of the appraisal, particularly for asset-based lending. The reason is that the lender needs to know what is included in the event of a default. Capitalized equipment normally includes the costs listed in Exhibit 9.3.

Machine Project Cost

Without seeing the source documents, the amount for just the machine is not known although the amount for the whole project is known but not confirmed. In a buyout of a plant, the total cost might be all that is requested. However, in asset-based lending, if there is a default and the property must be liquidated, only the value of the used machine would be recoverable. The appraiser may have checked source documents for some of the machines or none of them. If they were checked, the documents may be in the appraiser’s files but not in the report. Appraisers are required by the USPAP to keep in a file all the information regarding the appraisal.

It is also possible that the entry amount on the asset list could be inflated (there are several reasons this might have occurred), and an investigation of the source documents would be the only way to detect the problem.

The appraiser’s files should also include nomenclature on the machinery and equipment. This information is rarely in the appraisal, but the reviewer may want to request it if there are questions about certain high-value machines in the appraisal or if the reviewer needs to determine how thorough the appraiser’s work was. This is particularly important if the sales comparison approach was used because misidentifying a machine can lead to an inaccurate valuation. Terminology in the valuation is also often misunderstood, and the following definitions can help the reviewer.

Original Acquisition Cost. This is what the company paid for the item. It is not the current value. As previously mentioned, this number probably includes everything that was capitalized for the item, such as transportation of the item to the factory, installation costs, engineering and debugging costs, training, and sales tax.

Year Acquired. This is the date on which the item was purchased. It may or may not be the date that it was manufactured.

Year Manufactured. This is the year in which the item was made. It may differ from the year acquired because the item may have been purchased used.

Description. The items should be described adequately. Often, companies use a type of shorthand for a description that is not understandable to outsiders. The appraiser may have described the item so that it is more easily identified.

Asset Number. The asset should have a number that identifies it for the company’s accounting system.

Cost Center. Sometimes a cost center is assigned to assets according to their function, location, or the specific project they are related to.

Manufacturer’s Name. Generally this would be in the description, or the appraiser may have taken it from the nameplate.

Proprietary Equipment. This is equipment that is manufactured specifically for the company and is used exclusively by the company. Certain companies may make the equipment themselves, whereas others might have it made by an outside source. It is important that the appraiser state in the appraisal what equipment is proprietary because the value of such equipment is often diminished by the fact that it either cannot be sold to others or it has no value in the marketplace of manufacturing equipment because it has been customized for only one company.

If the equipment was built in house, the appraiser may have estimated the value based on the cost of materials and the man-hours used to construct it. This information would have come from the company because it would be necessary as a basis to capitalize the equipment for accounting depreciation purposes.

Serial Number. The serial number is assigned by the manufacturer, not by the company under appraisal. It helps the manufacturer identify the item if the appraiser needs more information.

Model Number. This is a number that identifies the machine for the manufacturer. It may also denote the size, capacity, and other attributes of the machine. It usually provides more general information about the particular model, whereas the serial number may provide more specific information. In some cases, the serial number may also include the model number.

Motor. The size of the motor may be rated in horsepower or electrical power.

Capacity. Many machines are rated by the amount of product they can process. For instance, presses come in various sizes and pressing capabilities. Plastic injection mold machines come in various capacities, and paper machines produce different widths and types of paper. The capacity can be one of the most important aspects in determining the value of a machine, so in reviewing an appraisal that uses the sales comparison approach, the capacity should be considered a major characteristic of the comparison.

Special Aspects and Customization. Machines are often ordered with special equipment or are customized for a particular use, which can greatly affect the value. Customized machines are not necessarily proprietary equipment. A customized machine is typically a standard machine that has been modified, whereas a proprietary machine is especially built or modified for the company from inception, to the extent that it is virtually unusable by other manufacturers.

History. The history can reveal the amount or hours of past usage, reconditioning, rebuilding, and repair work, all of which may affect the current value.

Estimated Useful Life. This estimate is related to the condition. The appraiser may have to estimate how many years the machine has until it must be rebuilt, becomes technologically obsolete, or no longer functions profitably. Most machines lose their tolerances and become less effective as they age. These judgments are based on a number of estimates, such as the current condition, years since overhaul or reconditioning, anticipated life based on other machines in the factory, and past reinvestment record for similar types of machines. Typically, this is rated in terms of “percent good.” A machine that is considered “30 percent used up” would be considered “70 percent good.” If the total life is 10 years, this means that the machine has 7 years of life left.

Running Time. Some machines have meters that show how many hours they have been run. In some plants, machines are run 8 hours a day, and in others they are run 16 or 24 hours a day. Some machines are used only intermittently because they are utilized for only certain production orders. This information is helpful in estimating the current value because the value is related to the condition.

Level of Maintenance. Even as individuals vary in the way they maintain their automobiles, companies vary in how well they maintain their equipment. Companies have different philosophies regarding this. Some companies prefer to have a large maintenance crew, and others use outside sources for maintenance. Often, the former types of companies maintain their equipment better because they are paying for the crew to be on site and can utilize their services daily.

Some companies invest heavily in maintenance, whereas others run their machines hard and replace them more often. Sometimes a company determines that its business is diminishing, so it decides to run the plant with minimum maintenance in anticipation of closing it once the equipment is worn out. For instance, this can happen in an area where the cost of raw materials or energy has increased for a particular product, or demand for the product has simply decreased. The company may figure that a profit can still be made for a certain amount of time if expenditures for optimum maintenance are not made. Exhibit 9.4 is a part of an asset list for a company.

Example of Part of a Company’s Asset List

The cost approach for machinery and equipment is based on the principle of substitution. The value of a used piece of equipment may be estimated by determining the cost of substituting a new piece of equipment that can perform the same function with equal utility and efficiency. Once the value of the new piece of equipment is found, it is then diminished by an appropriate percentage of depreciation to get the fair market value. Depreciation is an integral part of using the cost approach for machinery and equipment, and it is important to understand it in reviewing appraisals.

The definition of depreciate in Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary is, “to lower the price or estimated value of” and “to fall in value.” Depreciation is a loss of value for any reason and from all causes. It is measured by comparing the item under appraisal to its replacement or reproduction cost new.2

The difference between these two terms is as follows: reproduction cost means the cost to reproduce an exact replica of the machine under valuation, whereas replacement cost is the cost to purchase a machine that provides the same utility and function. Since technology is constantly changing, it is unrealistic to use reproduction cost in most cases. However, there is a large exception to this that will be discussed later in the chapter.

Often the replacement for a machine is more efficient than the original machine. These new efficiencies may mean that the replacement machine is superior to the old machine in a number ways, for any of the following reasons:

• It is less expensive.

• It is more expensive but more efficient; thus the savings outweigh the initial cost.

• It uses less energy.

• It is easier to operate.

• It needs fewer personnel to operate.

• It is smaller and perhaps lighter, taking up less space and being easier to transport.

• It functions with more precision.

• It keeps its tolerances and settings longer.

• It has more automatic features.

• It produces more product per hour (or other measurement unit).

• It requires less maintenance.

• It lasts longer.

• It does not last as long, but it is less expensive to buy and operate.

Although it is most always the case that a machine loses its value as it ages, it is also possible for a machine to increase in value since it was purchased due to inflation or other causes, and this will be discussed in the upcoming section on trending. The typical machine will lose value from one or more of the three forms of depreciation: physical, functional, and economic (economic is sometimes called external).

Physical depreciation (PD) involves deterioration of the item. Even if a machine is set up correctly when it is new, it will never again run as well because as it ages, tolerances are lost, and the result is a diminution in the quality of performance. Even a machine that is not used or is rarely used eventually deteriorates. Metal rusts and corrodes, and metal fatigue occurs simply from the stress produced by the forces of atmospheric pressure and gravity. If the machine is outside, the sun, rain, and wind cause erosion and other damage. As equipment is used, it continues to wear out, until eventually the equipment is no longer usable. Machines can be rebuilt, but they still have components that are not new, making them less valuable than new machines.

Physical depreciation can be determined in different ways. Observation is one way. Often the appraiser inspects the equipment as a first step in determining an estimate for physical depreciation, but it is not wise to base everything on the exterior appearance for obvious reasons. Large machines often have an hour meter that shows how many hours the machine has been run. Also, the company may have maintenance records that should reveal two things. First, the overall level of maintenance should be apparent from these records, which should give the appraiser an indication of how the company maintains all of its equipment. Second, the specific machine’s history should be recorded, giving the appraiser knowledge of when it was last rebuilt and how often it has broken down, among other things. In reviewing the appraisal, the reader should look for comments by the appraiser about the extent of his or her research and inspection of the equipment.

As a machine ages and is less productive, it generally requires maintenance at more frequent intervals. This maintenance may shut down a production line, slow down overall production, and become a drag on the production line. The expense of these problems can be called excess operating costs, which can be translated into a percentage of depreciation.

The second form of depreciation is functional obsolescence (FO), which is a loss in value because of an inadequacy or inefficiency in operation, as compared to a replacement machine, or as compared to the subject machine when it was new. A machine with this type of obsolescence may have symptoms such as inutility (that is, its usefulness is lessened), undercapacity, or excess operating costs. A machine that requires additional manpower to operate, as compared to a newer, more automated machine, is a good example of functional obsolescence that is manifested in excess operating costs.

The third type of depreciation is economic obsolescence (EO), which is depreciation that impairs the property because of detrimental influences outside the property. For this reason it may also be called external obsolescence. This is obsolescence over which the owner has no control and that also affects others in the same industry if they are in a similar location. An increase in the price of raw materials or utilities or rising labor costs would be applicable factors.

Other factors that could contribute to this type of obsolescence are the increased expense of, or imposition of, environmental regulations or diminished demand for the product manufactured. An example of environmental regulations causing economic obsolescence would be new clean air and water requirements for an industry such as papermaking or oil refining. The expense of meeting the new requirements, especially for an older facility, may be great enough to force the company to close the plant.

Technological obsolescence diminishes value because of advances in technology that render a machine obsolete. This type of obsolescence can occur to a new machine that has been warehoused but never used. Technological obsolescence is a form of functional obsolescence and is sometimes referred to as functional obsolescence. It may also be economic obsolescence because changes in technology are often external to a facility. The definition from the American Society of Appraisers says this:

Some appraisers draw a distinction between functional obsolescence and technological obsolescence. They define functional obsolescence as a loss in value resulting from differences in capability between a new machine and the appraised machine, and technological obsolescence as a loss in value resulting from the difference between design and materials of construction used in present-day machines compared with those used in the machine being appraised.3

There are three basic methods for applying depreciation, the market extraction method, the age-life method, and the direct dollar, or cost-to-cure, method. The market extraction method requires finding comparable sales, whereas the other two methods are applied to the estimated current cost (cost new) of the machine.

Market Extraction Method. The market extraction method requires finding comparable sales prices of similar equipment to extract depreciation. This method combines all the different forms of depreciation together because they are inherent in the sale price of the item used for comparison. Essentially, the market extraction method is a form of the sales comparison approach, and its accuracy is tied to the quality of comparable sales that are utilized. Adjustments may need to be made to the sales to compare them to the subject.

A simple example of market extraction is as follows. Machine A is being appraised. It is seven years old and cost $100,000 new. A search for comparable sales has been made, and three machines have been found that are similar to machine A—machines B, C, and D. These machines are six, seven, and eight years old, respectively. They have sold for $60,000, $55,000, and $52,000. The percentage of depreciation of the cost new for each machine would be 40 percent, 45 percent, and 48 percent, respectively. A choice in this range should be made for the subject’s depreciation—perhaps 45 percent since machine C is the same age as the subject. This example does not take into consideration installation, freight, and other costs, nor does it consider condition as compared to age. It is, rather, a starting point, used only to illustrate the theory behind the market extraction method.

Age-Life Method. This method of estimating depreciation is based on a ratio of the economic life to the effective age. All machines have a chronological age, which is the actual age of the machine, based on the date it was manufactured. A machine also has an economic age, or effective age, which is an age assigned by the appraiser to represent the condition of the machine.

Typically this age is greatly affected by the level of maintenance, overhauls, and amount of usage, among other things, that pertain to the machine. For instance, a machine may have a chronological age of 15 years. Because of excellent maintenance, its economic, or effective, age may be 7 years. If its total economic life, which is the time period the machine may be used for what it was intended to do, is 20 years, then a formula can be used to determine the percentage of depreciation that can be applied to it. That formula can be applied based on years of economic life or on hour usage:

Use/total use = percentage of depreciation

Therefore

7 / 20 = 35%

When this formula is applied to the property, the balance, which is 65 percent, is the percent good. The remaining economic life is 13 years. If the measurement of the machine is by hours run, then the same formula can be used based on the hours, rather than the years. However, it should be noted that simply using the hours of a machine does not take into consideration the condition of the machine, unless the hours are adjusted in conjunction with the maintenance and other upkeep. In the following example, the total hours of economic life assigned to the machine is 500, and it has been run 100 hours:

500 / 100 = 20 percent depreciation

The remaining economic life is 400 hours, which does not equate to years, unless the number of hours per year is estimated. For instance, if the machine will be operated for 40 hours a year, the remaining economic life will be 10 years.

Direct Dollar, or Cost-to-Cure, Method. The direct dollar method, also called the cost-to-cure method, involves estimating the actual expense of curing the value loss caused by the depreciation. Some elements may be curable, and others may not be. The appraiser estimates the curable elements and then translates that dollar figure into a percentage that is subtracted from the replacement or reproduction cost new.

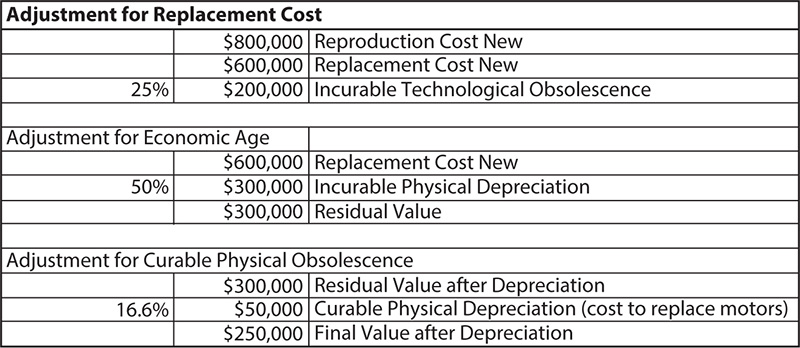

For example, a machine may need two new motors to operate optimally. The reproduction cost for the machine is $800,000. The replacement cost new (RCN), as shown in Exhibit 9.5, for a machine that is equal in utility but is not the exact machine, is $600,000. Therefore, the machine has incurable technological obsolescence of $800,000 divided by $600,000, or 25 percent. The machine also has a total economic life of 20 years and has been used for 10 years, so the economic life adjustment for obsolescence is 50 percent, leaving a value of $300,000 for the machine.

Adjustment for Replacement Cost

The motors cost $50,000 to replace. This number is subtracted last because its specific cost represents the diminution of value due to curable obsolescence. In other words, when the motors are installed, the value should be $300,000. The percentage for this amount is 16.6 percent, and the resulting value is $250,000. Exhibit 9.5 shows this in a different format.

There is an order of depreciation that should be followed. Using this method also helps the appraiser avoid double-counting the various forms of depreciation. It is as follows:

Replacement cost new (RCN) – physical depreciation (PD)

RCN – PD – functional obsolescence (FO)

RCN – PD – FO – economic obsolescence (EO)

RCN – PD – FO – EO = final value

Excess operating costs can be caused by physical depreciation when, for a variety of reasons, a machine becomes more expensive to operate than a new machine would cost to operate. Economic obsolescence can cause excess operating costs if, for instance, the source of energy necessary to operate a machine becomes too expensive. An example would be a machine that operates on electricity in a situation in which electricity increases in cost but natural gas decreases in cost and is an option with a different machine. Functional obsolescence can cause excess operating costs due to the expense of manufacturing with a machine that is not optimum for the task.

The typical methods used to determine the amount of functional obsolescence are the income approach or used-equipment approach. With the used-equipment approach, the value of the machine is found by comparing it to other, similar machines. For the income approach for a specific machine, the appraiser should have obtained operating costs from the company under appraisal. Sometimes costs can be obtained from equipment manufacturers, but they are neither as accurate nor as specific as information from the company under valuation. The optimum situation would be a company that has a new machine and an older one because then the costs can be compared.

These costs might represent savings in efficiency of the machine, including a requirement of less energy for operation, less manpower to operate, less maintenance, and faster production. The amount of the difference should then be adjusted for income taxes because the company realizes tax savings for the expenses that are incurred.

After that amount is subtracted, the savings are projected into the future, based on the remaining useful life of the equipment or the date the equipment is scheduled for replacement. A discount rate must then be chosen, and a present value factor must be utilized to get the value of the projected future savings.

To determine the excess operating costs for the whole plant, several methods can be used. If the appraiser can find sales for plants that are more modern or in some other way lack the obsolescence issue for the subject property, then he or she can use a sales comparison approach, just as the used-equipment approach (sales comparison approach) would be used for a specific machine, as previously mentioned.

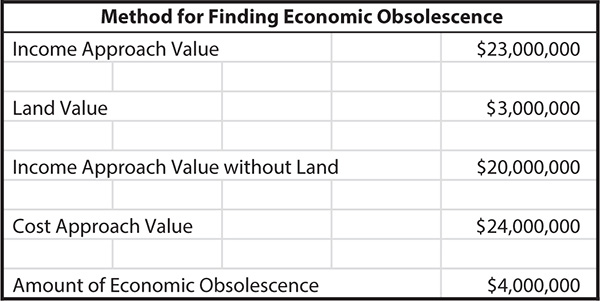

If comparable sales are not available, comparing the income approach to the cost approach is another method. The difference in the two values, after land is deducted, will to some extent be the economic obsolescence amount. Exhibit 9.6 is a simple example of this method.

Method for Finding Economic Obsolescence

In some situations, economic obsolescence can also be estimated using an income shortfall analysis. The concept is that the earnings produced by the plant do not justify the investment made in the plant. The following formula is an example:

(Expected return on investment − actual return on investment) / expected return on investment = economic obsolescence

There are other methods as well such as the gross margin analysis and return on capital analysis, but all of these methods are essentially measures of the performance of a company compared to what is or was expected of the company.4

Depreciation is often foundational to any industrial appraisal, and the main point that the reviewer should keep in mind is that the accuracy of the applied depreciation will affect the accuracy of the final valuation.