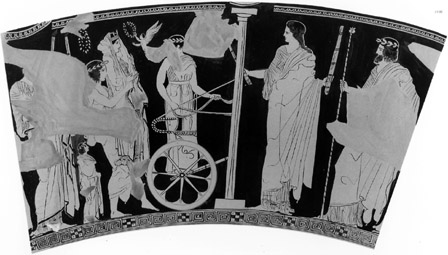

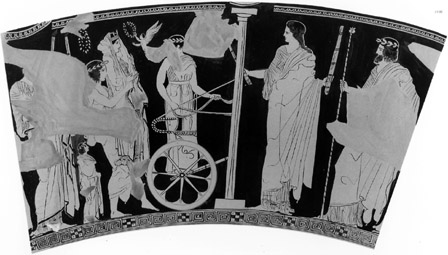

Figure 2.1 Attic red-figure loutrophoros, now lost. Previously in Berlin, Staatliche Museen F2372. After A. Furtwängler, Die Sammlung Sabouroff. I. Berlin: A. Ascher & Co., 1883, pl. 58.

Gloria Ferrari

It is difficult to determine precisely in which ways rites of initiation differ from other rituals in which Van Gennep recognized the tripartite schema that marks a rite of passage. Van Gennep’s chapter on initiations drew upon the work of Webster on secret societies and particularly Heinrich Schurtz’s study of age class societies and Männerbunde — the Greek polis (“city-state”) among them.1 If I were compelled to draw up a list of particular features of these rites on that basis, I would point to the following: an initiation involves integration into a group of like persons; it marks a profound change in the individual; and it is irreversible. That is, a priest who has been defrocked remains a defrocked priest and cannot go back to being a novice. The same may be said perhaps of other rites of passage, but is it true of betrothal and marriage? The idea that marriage is an initiation of sorts has been in the air for some time. Long before Vernant’s quotable phrase that “marriage is to a girl what war is to a boy”,2 the analogy between the coming of age of the young men on the one hand, and the marriage of girls occurs insistently in ancient sources. In the Demosthenic speech against Neaera, to give just one example, the speaker projects the admission of sons into the phratries and their inscription in the demes, on the one hand, and the giving of daughters in marriage as parallel, equivalent events, by which both girls and boys take their place in society.3 This is, of course, a fake symmetry, which scholars from Van Gennep to Brelich and beyond have explained away by pointing to the self-evident fact that “the social activity of a woman is much simpler than that of a man.”4 That is to say, marriage is as much of an initiation as a woman can accomplish. Support for the idea that marriage is an initiation has been found in the conceit, commonplace in Greek culture, that the death of an unwed maiden is a wedding in Hades or to Hades himself.5 The resemblance of certain features of the ekdosis (the “giving out” of the bride) to features of funerals have been stressed: the body is washed and dressed, it changes residence, accompanied by song and by torchlight, and both ceremonies involve feasts. These similarities — admittedly shared by other rites — have been explained by the hypothesis that the wedding produces in the woman an irreversible change and, as much as the funeral in the case of the corpse, it seals her incorporation in a new community. In brief, both weddings and funerals are initiations of sorts. But again this is a false symmetry, for although the funeral is an irreversible initiation rite, it remains to be seen precisely what kind of a transition a Greek wedding is.

What are we to make of a large body of evidence that stresses the impermanence of the marital union, the fact that the woman is denied full integration into the group to which she is now attached, and the fugitive character of female adulthood? I will now try to bring to the fore these ideas about marriage and womanhood, on the basis of the city-state about which we are best informed, Athens. What I have to say concerns the metaphors, which inform the Athenian conception of the wedding, that are embedded in legal formulas, ritual actions, and representations of marriage in poetry and visual representations.

The fundamental facts about marriage in archaic and classical Athens are generally agreed upon.6 One distinguishes two important moments, which Redfield characterized as a transaction and a transformation, respectively:7 the enguê, generally translated as betrothal; and the ekdosis, or formal transferal of the bride to the groom. The enguê was what distinguished the legitimate wife (damar or gunê gametê) from the concubine (pallakê) by endowing a woman with the capacity to produce children who in time would be citizens, as we learn from a law cited by Demosthenes, and attributed to Solon by some:8 “(she) whom father or brother or grandfather pledges or gives by enguê, from this woman are born legitimate children (gnêsious).” The marriage might follow immediately after the enguê or at a distance of time.9 The ekdosis is the occasion for elaborate rituals, lasting several days, three at least. On the day when the bride was given to the groom, the anakalyptêria, there would be a banquet for the two families and friends, normally at the bride’s house. At some point the bride would be “uncovered” or “unveiled” and honored with gifts. The transport from the house of her father or guardian (kurios) to that of her husband took place in the evening by the light of torches. In her new residence more ritual marked the entrance of the bride in the husband’s oikos (“household”): the eating of a special food, a quince or pomegranate, and the showering of the pair with a basketful of dried fruits and nuts. With the consummation of the marriage began cohabitation.

There has been considerable debate in the past hundred years as to which of these actions meets a juridical definition of marriage.10 At no point in the procedure was there a moment at which the bride consented to the marriage. The only step that had legal consequences was the enguê, for which not even her presence was required. The enguê insured the status of children, which might be born, should the parties involved actually ever enter into cohabitation.11 But a woman thus promised might never be given away. The non-binding quality of the enguê, coupled with the fact that no other part of the procedure was in itself constitutive of marriage in the legal sense, leads one to conclude with MacDowell that “the legal difference between enguê and gamos was, roughly, that enguê was making a contract and gamos was carrying it out.”12

From the facts of the matter, I now turn to the poetic qualities of legal formulas, to consider first the ekdosis and then the enguê. In the case of the Athenian wedding, the proceedings are governed by a basic metaphor of commercial transaction, out of which spins a series of interrelated metaphors that are employed in rituals and in literary imagery.

What we call giving away the bride is expressed in epic with the simple verb “to give” (didonai). In classical Athens didonai may again be used, as it is, for instance in Menander’s use of the formula, in which, with affected primitivism, the bride is “given” for the plowing.13 But the technical term for the conveyance of the bride is ekdosis and the verb ekdidonai, literally “to give out”, as it used, for instance by Isaeus, where the speaker’s mother’s legitimacy is demonstrated by the facts that she was “given out” (ekdotheisan) by her father, as well as being “pledged” (egguêtheisan) by him.14 Wolff demonstrated in 1944 that ekdosis is the term used of the lease in contracts for “a transfer which […] conferred title upon a transferee, but at the same time reserved a right for the transferor.”15 In this sense it is employed of objects of contracts for work, of slaves handed over for questioning by torture in lawsuits. In papyri it refers to the handing over of the baby to the wet nurse, and of an apprentice to a master. In Xenophon’s tract on horsemanship, for instance, ekdidonai is used both of giving one’s son out as an apprentice and of entrusting a colt to a trainer (On Horsemanship 2.2). The ekdosis, that is, is not a gift of the bride to the groom, but a conditional lease for the expressed purpose of producing children, who will be citizens. The metaphor is apt. Her natal family never totally relinquished its control over a married woman and the dowry that went with her, both of which might revert to it for a variety of reasons.16 We are best informed about cases in which a married woman came into an inheritance, becoming epiklêros (“heiress”) and could be, and was claimed by her nearest male relatives on her father’s side.17 A man would divorce his wife to marry an epiklêros. But marriages could be terminated for no particular reason and there is general agreement that divorce was easily obtained, although there is debate on how frequently it actually occurred.18 To this add the married woman did not become part of her husband ankhistheia, the group of kin with rights of inheritance.19 She remained, in a real sense, a stranger in the house.

No less than ekdosis, enguê is used for a range of commercial transactions that require a guarantee, or the establishment of securities.20 One pledges himself as surety in the middle voice, and the thing which is pledged is the enguê, a sum of money in the case envisaged in Demosthenes’ speech against Apaturius, who, had Demosthenes truly become guarantor (enguêmenos) for Parmeno, would surely have demanded the sum guaranteed (enguên) at once (33.24). The word is also used for posting bail, as in the case of the law introduced by Timocrates, cited by Demosthenes: sureties were established for the payment of bail money (24.40). One understands the relationship between the two meanings of the word intuitively to mean that the future bride is pledged.

The noun enguê and the verb enguan contain an image, upon which the understanding of the procedure of enguê and of its import rests. Since antiquity that figure has been reconstructed on the basis of a hypothetical etymological derivation of enguê from guion, the hand, the hollow or palm of the hand.21 This has led to seeing the enguê as a “handing over”, which has taken two distinct forms. Wolff understood enguan to mean “to hand over” and enguasthai “to receive into one’s hands”. He explained the use of the same term for both guarantee and betrothal on the model of the Germanic contract of suretyship: “guarantee was contracted by handing over the debtor to the guarantor who was to exercise control for the purpose of keeping the debtor at the creditor’s disposal.”22 Accordingly, the bride would be placed in the groom’s keep but kept at her father’s disposal. This metaphor is inept in several obvious respects, the most important of which is that it is not at this stage that the bride is given to the groom. Gernet’s explanation has won favor that the term originally meant a solemn promise made on behalf of the family group, rather than the transferal of an object or person. In his view, what is put in the hand is a pledge, signified by a handshake.23 This rationalizes the metaphor implicit in enguê, but does not bring its focal image into focus. What is the thing that is placed in the hand? The fact of the matter is that in the enguê nothing changes hands, except, sometimes, the dowry.

According to Chantraine, the Greek words guê,guia,gualon constitute a group of terms that go back to the notion of “hollow”, and “vault”. “The concrete sense of the group, he writes, appears in the substantive gualon, which designates various kinds of “hollows”.24 This, I believe, is the image we are after.

Hesychius defines guala as store-rooms for treasure, treasuries, and hollows,25 but guala may also be said of cups and of the canopy of heaven. What holds together these various meanings is the image of a hollow space as a container. A dominant image is that of the stony hollow and the cavern. In the Hecale, the great stone under which Aegeus places the sword and the boots for Theseus to find once he grows strong enough to lift it is gualon lithon.26 Guala may be valleys, such as the valleys of Pieria, which hold the tomb of Euripides, in an epigram by Ion.27 In Pindar’s Nemean 10, the Dioscuri, who share one life by spending each alternate day on earth and the other in Hades, are said to be in the caves of Therapne, en gualois, deep under the earth.28 In Euripides’ Andromache 1092–5, the underground caverns at Delphi are both caverns and treasury, they are caverns filled with gold: “See that man who moves along the god’s caverns (guala) filled with gold, treasure-houses (thesaurous) of mortals, who comes again with the same aims as he did when he came before, to sack the temple of Phoebus?” Here, as elsewhere, the sense of gualon is akin to that of English “vault”. The sense of depositing something of value in the vault underlies the metaphoric use of enguê in the Eumenides 894–8, in the final exchange between Athena and the Furies, which is shot through with metaphors of commercial exchange:

CHORUS: Now suppose I have accepted. What reward (timê) is in store for me?

ATHENA: That no household shall flourish without you.

CHORUS: Will you bring this about, that such power be mine?

ATHENA: We shall raise the fortunes of the one who reveres you.

CHORUS: And will you lay in store for me the fund (enguên these) of all time to come?

To Athena’s offer of hospitality the chorus replies by asking what their compensation will be — timê, a word that means “honor” but also “reward” and “price.” Athena promises to augment the fortunes of those who hold them in awe. When the chorus ask if this will be forever, they use the expression enguên these, will you set, lay down, or deposit, as in a bank, an enguê of all the time to come?

I believe that the image of laying valuables in store in a vault, or an underground vault, is the one that structures the sense of enguê as “deposit”, one that suits its use both as guarantee and betrothal. I should make it clear that this is not a matter of tracing the etymology of the word, but of recovering the vehicle of the metaphor that shapes the very concept of enguê.29 For an understanding of the way in which enguê and ekdosis follow one another as stages of one and the same process, I rely on Benveniste’s explanation of the peculiar semantic development connecting the expressions for hiding, burying, on the one hand, and giving out and lending, on the other, in Gothic.30 While filhan means “to hide, to withdraw from sight”, corresponding to Greek kruptein, ana-filhan, equivalent to Greek ekdidosthai, means “to give out”, “to lease”, “to farm out”. The German practice of burying resources and valuables, Benveniste reasoned, underlies the idea that goods that may be leased are buried treasure, which is unearthed at the moment of conveyance. What comes into play — not surprisingly — is the image of the bride as treasure.31 The fact that the female is “spoken for” is cast in the figure of capital withdrawn from circulation and placed in the vault, from which she will be taken out when the moment comes to hand her over to the groom. As well as the contractual partnership of two men in the production of children for the state, the enguê then marks the beginning of the woman’s rite of passage, the stage of separation.

The poetic force of the metaphor of the bride as buried treasure informs the next phase of the marriage ritual. An important phase of the gamos (“wedding”) was the anakaluptêria, which is mentioned for the first time in a fragment of the cosmogony of Pherekydes of Syros, to be considered shortly. Most of our information, however, comes from later sources, which explain that, on that occasion, the bride was “uncovered”. The idea took shape long ago that the play of concealment and revelation that the word implies was acted out through a formal unveiling of the bride. There is now general agreement that the term was “used for both the ceremonial unveiling of the bride before the bridegroom and also for the gifts given by the groom to the bride immediately following this unveiling,”32 but one should note that anakaluptêria never means an act of unveiling.33 The term was used to designate the day on which the bride was “uncovered”, or “unveiled”, for the groom to see, and also for the gifts she received on that day from the groom, relatives, and friends.34 The lexicographers give theôrêtra and optêria as synonyms, both signifying seeing, as well as prosphthenktêria, which emphasizes the fact that the bridegroom addressed the bride.35 The singular anakaluptêrion signified the moment when the bride was brought out, on the third day, as well as a gift given on that occasion.36 Debate continues over the place occupied by the unveiling in the sequence of events that constituted the wedding ceremony, but a few points seem secure.37 One source specifies that the bride was uncovered at the wedding feast for the husband and guests to see.38 Since that was the moment in which she first became visible, the bride’s uncovering must have taken place before the couple’s voyage to the husband’s house, on foot or by wagon.39

Reasonable as it seems, the hypothesis that there was a ceremonial unveiling runs into difficulties, in part because it is difficult to decide what form the veiling took, in part because not every unveiling is an anakaluptêrion. We have literary and visual evidence to the effect that the bride was well-covered during and after the banquet. A caricature of the procession on a classical Athenian pyxis shows her entirely wrapped, for example.40 Lucian (Symposium 8) writes of the strictly veiled bride at her own wedding feast. And a metaphor in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, 1178–9, which is sometimes brought forward in support of the unveiling,41 seems to say precisely the opposite. In that passage, Cassandra says: “no longer will my prophecy peek out from under veils, like a newly wedded bride (neogamou numphês dikên)”. The neogamos numphê is the bride, but the bride just married, not the bride-to-be. In addition, the newly wedded bride’s mantle, or veil, figures prominently in representations of the marriage procession, whether by chariot or on foot, in archaic and classical art. On Athenian black-figure vases it is a richly woven affair that she wears drawn over her head and holds out to shield her left cheek, in a distinctive flourish that is in part a display of decorum and in part sheer display. In kind, the “bridal gesture” as it is called, is an exaggeration of the act of veiling oneself, which is performed by all persons possessed of aidôs.42 Thetis holds this pose standing in the chariot, surrounded by the gods,43 but even the protagonist of the Amasis Painter’s modest wedding by mule cart parades her oversize mantle with ostentation.44 The bridal gesture is rare on late archaic and classical Athenian vases, but the mantle is no less in evidence. When the procession is on foot, attention is drawn to it by the fussy gesture of an attendant, the nympheutria, who follows the bride as the pair approach the marriage chamber, adjusting the way the mantle falls on her head, or on her neck and shoulders.45 On a black-figure tripod-pyxis of the early fifth century, for instance, is the picture of the cortege arriving at the newlyweds’ thalamos (“wedding chamber”). This is the wedding of Heracles and Hebe, and behind Hebe the woman arranging the bride’s mantle may be Aphrodite.46 On the skyphos by Makron, it is indeed Aphrodite who arranges Helen’s mantle, as the latter is led away by Paris, as though a bride.47

Evidence of the importance of the bride’s mantle is not limited to vase-paintings. From the sanctuary of Persephone at Locri come series of votive terracotta plaques decorated with subjects related to the marriage of Persephone and Hades. These include one series depicting a cortege bringing the mantle, which lays folded upon a tray, and a deep cup.48 The mantle is at center stage on the metope from the temple of Hera at Selinus, which represents a marriage of divinities, probably Zeus and Hera.49 The god, seated, grasps the bride’s wrist in the traditional gesture of marriage. She stands before him, framed by the great mantle. The display of the mantle characterizes Hera among the gods on the East frieze of the Parthenon, advertising the fact that she is the “lawfully wedded wife” (koundiê alochos) of Zeus. Does this gesture signify the ritual unveiling at the anakaluptêria? Twice in literary imagery the figure indeed marks the moment at which the bride meets the groom. In a fragment of Euphorion, the city of Thebes is said to be the anakaluptêrion (here: “wedding gift”) of Zeus to Persephone, “when she was about to see her husband for the first time, turning aside the cover of her nuptial mantle.”50 Centuries later, Philostratus describes a painting of Pelops and his bride Hippodamia in the chariot, “she arrayed in nuptial attire, uncovering her cheek, now that she has won the right to a husband” (Imagines 1.17.3).

There remains to be considered, however, what is arguably the most important testimony for the ceremony: its foundation legend (aition), which survives in part in a fragment of the sixth-century cosmogony of Pherekydes of Syros. The anakaluptêria, Pherekydes says, has its origin in the marriage of Zas (= Zeus) to Chthonia. This is preceded by the creation of his grand oikos, consisting of houses and possessions. On the third day, Zas weaves the whole world into a great mantle, pharos. There follows a lacuna, after which we find Zas offering this mantle to Chthonia and asking her to unite with him. Accepting the mantle, she makes her reply, but at this point the text breaks off:51

For him they make the houses many and great. And when they had finished providing all this, and also furnishings and men-servants and maid-servants and all else required, when all is ready, they carry out the wedding. On the third day of the wedding, Zas makes a mantle (pharos), large and fair, and in it he weaves Earth and Ogenos and his dwelling […] “For wishing your marriage to take place, I honor you with this. Therefore receive my greeting and be my wife.” This they say was the first anakaluptêria, and hence arose the custom among gods and men. And she answers him, receiving the robe from him […].

It is apparent that the information we have about the anakaluptêria breaks down into categories according to the genres of our sources. In the antiquarian and anecdotal material furnished by the lexicographers, one finds no mention of the mantle in connection with an unveiling, and the bride does not uncover herself, but is uncovered. The visual and literary imagery, on the other hand, focuses suggestively on the figure of the mantle and on the gesture by which the bride uncovers herself. And at the heart of the foundation legend is a very special mantle, which the bride does not take off but receives, at a point at which she is obviously in the presence of her groom. These are not contradictory accounts. Rather, one may think of them as representing different points of view of the same event. Understanding the nature of the ceremony involves, therefore, a kind of triangulation, mapping the relationship of the archetype of all anakaluptêria to come -- its aition -- to ritual actions and to perceptions and folk-explanations of those actions. The symbolic import of the mantle can hardly be overplayed, and that shall be our starting point. The robe appears indirectly in another fragment of Pherekydes, where we learn that “Zas and Khronos existed always, and Chthonia; but Chthonia acquired the name Ge (Earth), since Zas gives the earth to her as a gift of honour (geras)” (frag. 14 Schibli; translation Freeman 1948, modified). As Schibli notes,52

The geras is the embroidered earthrobe, the gift of honour and wedding present for the bride of Zas. … The bestowal of the robe upon Chthonia signifies not only a bridal gift but also an official act of investiture by which she becomes Ge.

In the symbolic function of the mantle in the wedding of Zas and Chthonia, we have an explanation of the role of the nuptial mantle in visual representations of the wedding and the wife. This is the first of a series of correspondences between the foundation legend of the anakaluptêria and its earthly performance. Zas’s bride is Chthonia, “she who is beneath the earth”. Like the word enguê, her name evokes the image of the bride in subterranean confinement, from which she emerges on the day she meets her husband. Chthonia undergoes a transformation. The turning point is her acceptance of the mantle, when the groom addresses her for the first time.53 With the great mantle (pharos), she receives the earth as her domain and becomes Earth herself. The mortal bride’s transformation into fertile ground is stated in the classic marriage formula that casts her in the shape of arable land: “I give you this woman for the sowing of legitimate children.” The explanatory legend for the anakaluptêria thus contains the blueprint of the symbolic structure of the wedding, which should guide our interpretation of the disparate fragments of evidence for the ritual. The “uncovering” that gives the day its name refers primarily, I suggest, to the emergence of the bride into sight, from figurative seclusion in enguê. This is in line with the testimony of Hesychius, who defines anakaluptêrion as the bringing forth of the bride.54 We are not told how the mortal bride acquired her nuptial mantle, nor at which point in the proceedings she put it on.55 It is possible that it came to be understood simply as nuptial attire, but the votive reliefs from Locri, mentioned above, may indicate that this garment was the focus of ritual acts that have left no trace in the literature. It is likely that the bride wore the nuptial mantle as she emerged from her chamber, at once revealed and veiled. Poised in the bridal gesture, she exposed her face to the groom, shielding it, at the same time, from the other men present. Whether or not this act was ritually significant remains to be seen. It certainly came to be perceived as having symbolic import, as the passages of Euphorion and Philostratus cite above demonstrate.

In the donning of the wife’s mantle I would identify the liminal phase of some kind of rite of passage. But does this action also produce a profound change in the bride and mark the beginning of her incorporation or initiation into a new community comparable to that secured by funeral rites for the dead?

The conceit that the death of a maiden ready for marriage (the numphê) is a marriage in Hades or to Hades, is commonplace in funerary epigrams and frequently exploited on the Athenian tragic stage. Significantly and poignantly, the moment of death is often made to coincide with the anakaluptêria, particularly the wedding procession. For example, Erinna’s epitaph for Baucis (Anthologia Palatina 7.712) tells us that Baucis died when the cortege had reached the groom’s house: her father-in-law lights the funeral pyre with the torches that had lit her wedding procession; the wedding songs (humenaia) turned into dirges. A number of studies produced over the past twenty years have analyzed these and many other examples, in which the death of a maiden or a bride is represented as a marriage in Hades or to Hades himself. These analyses have stressed points of resemblance between the rites of ekdosis and funerals. It is now a widely accepted proposition that the correspondences between wedding and funeral are made possible by the fact that the two rituals are structurally alike. Seaford gave an influential formulation of this idea:56

A transition effected by nature (death) is enclosed by the imagination within a similar transition effected by culture (marriage). It is important to observe that this enclosure is facilitated by the presence in the wedding of elements associated with death, to some extent perhaps actual lamentation, but, more importantly ‘equivocal’ elements common to the two rites of passage.

One speaks, accordingly, of an “interpenetration”, or a “conflation of marriages and funerals”, in a way that implies that marriage is as much a death as death is a marriage. Against this interpretation of the “Bride of Death” topos in tragedy, funerary epigrams, and visual imagery stands the fact that, while the bride’s death may be cast as a marriage, a marriage is never cast as a death. “Bride of Hades”, in other words, is a metaphor, in which a very special type of death is projected through the vehicle of the wedding. As any metaphor, it demands that we distinguish between vehicle and tenor, and that we know which parts of the metaphoric image to focus on, and which ones to ignore. In this case, we know that the bride’s journey to her new home is not irreversible and that, far from abandoning her, her kin retains control over her. The metaphor turns suggestively upon the imagery of the anakaluptêria, particularly the procession: the torches, the songs, the chamber. The funeral procession and the marriage cortege, however, are not analogous, but one the reversal of the other, moving, as it were, in opposite directions: the first follows the uncovering, the “bringing out” of the woman, the latter moves toward her burial.

Fundamentally, the conceit of the marriage in Hades relies on a root metaphor, which is frequent in Greek, that of the grave as a thalamos, the place of sleep. This image is employed in the case of the maiden ready for marriage with a particular twist. The particular thalamos to which she is consigned is projected as the one in which the marriage would be consummated: the room with the nuptial bed, the numpheion. The difference between the bland figure of the grave as the final resting place and the grave of the bride is the difference between a death that is perceived as part of the natural order of things and a death that comes unfairly at the wrong time. The dead numphê is aorê, “untimely dead”, and her grave is charged with chthonic potency and makes an excellent conduit to the infernal powers.57 The death of the woman of an age to marry is a violation of both the natural and the social order. It opens up the vision of the world upside down, where the young die and females do not give birth, where things can be truly perceived only by looking at them backwards.58 Wedding songs and dirges, wedding torches and funeral torches, the wedding banquet and the meal that follows the funeral are not analogous to one another, but represented as polar opposites to convey the idea of an inverted ritual. When a maiden ready to marry dies, and particularly when she is murdered, the normal order of things is reversed and the ekdosis is replaced by the enguê, with horrible results.

In Sophocles’ Antigone this conceit is deployed in a sustained manner, making use of the image of the cavern, the stony hollow. Thebes is a city where cultural norms have been turned upside down, where the dead lay unburied, where it is left to a woman to stand up for what is right. Antigone openly defies Creon’s edict, which prohibits the burial of her brother’s corpse. The king of Thebes is as well her present guardian (kurios) and future father-in-law, since she is betrothed to his son Haimon. Creon should deliver Antigone to the groom, but he does the opposite. Instead of “giving her out”, Creon buries her in “a rocky cavern” (774), to which she is led as though to a bridal chamber — “the hollowed rock, death’s stone bridal chamber” (1204–5). The exclamation of Antigone as she enters the cavern is deservedly the most famous expression of the metaphor of the grave as numpheion (891–4): “Tomb, bridal chamber, prison forever dug in rock, it is to you I am going to join my people, that great number that have died, whom in their death Persephone received.” Note that Antigone is not the bride of Hades: let her marry someone in Hades, Creon says (654); Hades leads her alive to the shore of Acheron, but to marry Acheron (808–10); and, in the end, she marries Haimon, in Hades (1240–1).

Antigone’s infernal wedding is emblematic of the world upside down over which Creon rules. Tiresias reveals to him the monstrosity of his policies (1068–71):

You have thrust one that belongs above below the earth, and bitterly dishonored a living soul by lodging her in her grave; while one that belonged indeed to the underworld gods you have kept on this earth without due share of rites of burial, of due funeral offerings, a corpse unhallowed.

This passage unambiguously proposes the death of the bride as a prime instance of normative inversion and the polar opposite of the wedding. For marriage to Hades, or in Hades, is no marriage at all: no humenaia (“wedding hymns”) accompany Antigone to the shore of Acheron (806–14); she will have no bridal bed, no bridal song, no joy of marriage, no portion in the nurture of children (916–20):

And now he takes me by the hand and leads me away, unbedded, without bridal, without share in marriage and in the nurturing of children; as lonely as you see me; without friends; with fate against me I go to the vault of death.

Most importantly for present purposes, death is a state from which a woman will never emerge, and that is not true of marriage. The dead person is

Figure 2.1 Attic red-figure loutrophoros, now lost. Previously in Berlin, Staatliche Museen F2372. After A. Furtwängler, Die Sammlung Sabouroff. I. Berlin: A. Ascher & Co., 1883, pl. 58.

permanently separated from the living and incorporated into the community of the shadows; the boy is initiated into the polis. Neither can ever go back to what he was before. But a woman can cross the threshold of marriage many times over, unaccompanied by ritual on the reverse journey, becoming each time a bride again, to be pledged and given out, to be revealed again for the first time and carried off with torches raised high and the singing of humenaia and hymns, under escort. “Twice given out, twice pledged” (dis ekdotheisa, dis enguêtheisa) says the speaker of one of Isaeus’ speeches of his mother with understandable pride (8.29). The process that makes a maiden into a wife and mother entails, the first time, the loss of parthenia (“maidenhood”) but does not produce any change in her as a social being. One might say of marriage what Lincoln has said of female “initiations” in general: “Status is the concern of the male, and women are excluded from direct participation in the social hierarchy. The only status that is independently theirs, if status it be, is that of woman.”59

The wedding is surely a rite of passage, but not one that left indelible marks on the object of the ritual. Rather than with initiations, it has affinities with what Van Gennep called “rites of appropriation”, “whose purpose it is to remove a person from the common domain in order to incorporate him into a special domain: rites of sacred appropriation of new lands, the transfer of relics, or of statues of gods”. For this reason, perhaps, the transfer of the bride to her husband’s house is the defining moment of the marriage in the imagery of the wedding, as on a Classical loutrophoros (fig 2.1). “The act of carrying”, Van Gennep writes, “is in this context the performance of a transition rite.”60

A fuller version of this chapter appeared in chapter 8 of Ferrari (2002).

1 Van Gennep (1960) ch. 7; Webster (1908); Schurtz (1902).

2 Vernant (1974) 65.

3 [Demosthenes], Against Neaera 122: “For this is to be married, to have children and to introduce the sons into one’s phratry and one’s deme and to give out the daughters to the men as one’s own.”

4 Van Gennep (1960) 67; see also Brelich (1969) 42–3.

5 The striking use of wedding imagery in laments was fully analyzed by Alexiou and Dronke (1971) 819–63. See, further, Jenkins (1983); Seaford (1987); Rehm (1994).

6 Vérilhac and Vial (1998) give the latest exhaustive survey of sources for the ancient Greek marriage.

7 Redfield (1982) 188.

8 Demosthenes 46.18. The procedure is not limited to Athens. Herodotus, 6.57.4, refers to marriage by enguê at Sparta, and, according to Diodorus Siculus, 9.10.4, “by most of the Greeks the marriage contract is called enguê.” On the diffusion of this term see Vatin (1970) 157–63.

9 Vérilhac and Vial (1998) 229–58, argue unconvincingly that enguê and ekdosis are two words for one and the same act of “giving” the bride, which is, in turn, distinct from the gamos.

10 Wolff (1944) remains of fundamental importance. For a recent attempt to recover in Greek marriage practices the structure of a quasi-legal process that might resemble Roman marriage procedures, see Patterson (1991) and Patterson (1998) 107–14.

11 Wolff (1944) 51–3. Vérilhac and Vial (1998) 229–32, review the history of scholarship on the enguê. As a historical example of an enguê that has no effect, one often cites the notorious case of Demostenes’ father, who near death pledged by enguê his wife to Aphobos and his five-year-old daughter to Demophon; Demosthenes 28.15–16; 29.43; Harrison (1968) 6–8.

12 MacDowell (1978) 86.

13 Perikeiromene 1013–14. Occurrences of this formula in ancient authors are collected by Vérilhac and Vial (1998) 232–3.

14 Isaeus 8.29: “For distant events I furnished hearsay vouched for by witnesses; among those who are still alive, I produced those who are familiar with the facts, who knew well that my mother was brought up in his house, that she was regarded as his daughter, that she was twice given out in marriage (ekdotheisan), twice pledged (enguêtheisan).”

15 Wolff (1944) 48–51, the quotation from p. 48.

16 Wolff (1944) 47, 50, 53–65. Gernet (1983) 210: “Au total, la femme est un instrument; et même mariée au dehors, elle n’est jamais ni intégrée au groupe de son mari, ni détachée de son groupe original. Les significations de la dot sont en rapport avec l’institution matrimoniale: le mari ne devient jamais propriétaire de la dot, laquelle est transmise aux enfants s’il y a des enfants — et, s’il n’y en a pas doit toujours être rétrocedée au constituant. Elle est l’accompagnement symbolique de la femme qui, en un sens, n’est jamais que ‘prêtée’.”

17 Just (1989) 95–104, gives a clear and concise exposition of the rules governing epiklêroi at Athens. For a broader, if tendentious, overview, see Patterson (1998), 91–106.

18 Gernet (1983) 207; Cox (1998) 71–72; Thompson (1972). Cohn-Haft’s thesis (1995), that divorce was infrequent has all the weaknesses of arguments from silence.

19 Just (1989) 85–9.

20 Just (1989) 85–9.

21 Chantraine (1968–80) 240.

22 Wolff (1944) 52.

23 Gernet (1917) 249–93, 363–83, particularly pp. 365–73; Harrison (1968) 3–6. Sutton (1989) 334–51 tentatively identified the enguê in the representation of an old king shaking hands with a youthful traveler on the loutrophoros in Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 03.802. There may be an allusion here to the wedding to come, which is represented on the other side of the vase. In and of itself, however, the handshake need be no more that a gesture of greeting.

24 Chantraine (1968–80) 239.

25 Hesychius s.v. “guala.”

26 Callimachus, Hecale frag. 235–36: “For in Troizen he put it [the sword] under a hollow stone together with the boots … whenever the child should be strong enough to lift with his hands the hollow stone.”

27 Anthologia Palatina 7.43: “Hail Euripides, who inhabit the chamber of eternal night in the dark-leafed valleys (en gualoisi) of Pieria! Know that, although you are under the earth, your glory shall be everlasting, equal to the perennial grace of Homer.”

28 Pindar, Nemean 10, 55–6: “Changing in succession, they spend one day with their dear father Zeus, the other in the caves (engualois) of Therapne deep under the earth.”

29 On images as metaphoric expression and their cognitive function see Ferrari (1990); Ferrari (1997); Ferrari (2002) ch. 3.

30 Benveniste (1969) 159–61.

31 Of particular interest here are Gernet’s observations, in his essay on the mythical concept of value, connecting the idea of thesauros as a “vault … dug into rock and covered with a lid” with the thalamos, where a wife or daughter would be kept; see Gernet (1968) 129–30.

32 Oakley (1982) 113; Vérilhac and Vial (1998) 304.

33 The term anakalupsis, commonly used in modern scholarship on the Greek wedding, apparently occurs only once in extant literature, in Plutarch, Moralia 518D1, to mean “disclosure” of some sickness. In formation, anakaluptêria is analogous to, e.g., anthesteria, the festival of flowers, and means “the feast of anakaluptein”; see Chantraine (1933) 62–4. Whatever form it took, the uncovering was only one part of the anakaluptêria, since the festal day identified by that name included as well the banquet, the procession that accompanied the newlyweds to their destination, and the reception of the bride in her new oikos. The word itself might be used, therefore, for other moments of that day. The historian Timaeus (FGrH566F122), for instance, reports that Agathocles of Syracuse abducted his niece, who had been given to another man, “from the anakaluptêria”. The theft is likely to have taken place during the procession, the classic moment for attempts on the bride, who traveled under escort precisely in order to guard against attacks of this kind; see Deubner (1900) 149; Toutain (1940) 345. On the escort guarding the bride and cases of attempted seduction and rape on route, see Oakley and Sinos (1993) 27.

34 Pollux, Onomasticon 3.36; Harpocration, s.v. “anakaluptêria”. See also Suda, Lexicon, s.v. “anakaluptêria”; Deubner (1900) 148–51.

35 See above, n. 34, and Pollux, Onomasticon 2.59.

36 Hesychius, s.v. “anakaluptêrion.”

37 The view that the unveiling preceded the procession is represented by Deubner (1900) 149–50; Patterson (1991) 68n. 40; Oakley (1982) 113–14. For the hypothesis that it took place at the groom’s house, see Toutain (1940); Sissa (1990) 97–8; Rehm (1994) 141–2; Vérilhac and Vial (1998) 304–12. Harpocration (above n. 34) has been accused of confusing the anakaluptêria with the epaulia, which was the day after; Deubner (1900) 148; Oakley (1982) 13 n. 5; Vérilhac and Vial (1998) 304 n. 68. On the epaulia, according to the lexicographer Pausanias, quoted by Eustathius at Iliad 24.29, a procession brought the gifts to the groom’s house, as well as the dowry. To this list the Suda, s.v. “epaulia”, adds khrusia (“jewelry”). Together with the mention of the dowry, this suggests that the epaulia does not involve a second wave of wedding presents, but was the formal delivery of the gifts that had been assembled in the bride’s house on the anakaluptêria; see Zancani Montuoro (1960) 48–9. Harpocration’s statement, therefore, may beinterpreted to say that anakaluptêria is the name of the gifts given on the occasion of the anakaluptêria, and that another name for the same gifts is epaulia, the occasion when they were ceremonially delivered to the groom’s house.

38 Bekker (1814) 200.6–8 (=390.26).

39 Deubner (1900) 149,151, followed by Oakley (1982) 113–14, and Patterson (1991) 68 n. 40.

40 “Salt-cellar”, Bonn, University 994; On this and other vase paintings of the bride with her face covered, see Oakley and Sinos (1993) 31–2, 137 n. 63, figs. 68–70

41 Rehm (1994) 47.

42 On aidôs and veiling see Ferrari (1990). The term aidôs is untranslatable, but in this context “modesty” comes closest.

43 Attic black-figure hydria, Florence, Museo Archeologico 3790; ABV, 260, 30.

44 New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art 56.11.1, Paralipomena, 66; Beazley Addenda, 45.

45 Oakley (1982) 116 n. 16. Many examples are illustrated in Oakley and Sinos (1993); see fig. 85 (loutrophoros in Athens, National Museum 1174); fig. 90 (pyxis Louvre L 55); fig. 94 (loutrophoros in Copenhagen, National Museum 9080); fig. 106 (loutrophoros in Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 03.802);

46 Oakley and Sinos (1993) 35, figs. 100–4. Much attention has focused on a classical loutrophoros in Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 10.223, which offers a representation of the bride and groom seated facing one another, in the presence of a young man, while a woman pours down on them a basketful of small objects. Behind the bride, an attendant lifts the veil or mantle from her forehead. Sutton (1989) 351–9, identified in this picture the katakhusmata, the showering of the newly married woman with dried fruit and nuts upon her arrival at the groom’s house. Following Beazley, ARV2, 1017, 44, and Sutton, 358,I believe that this action should be understood as a veiling, rather than an unveiling. As in the examples just cited, it is a means of emphasizing the mantle or veil, not, as Oakley (1982) 114–8, has argued, its removal.

47 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 13.186; ARV2, 458,1; Oakley and Sinos (1993) 32–3, fig. 86.

48 Zancani Montuoro (1960) 40–50; Prückner (1968) 42–5.

49 Marconi (1994) 142–4, 276–90.

50 Euphorion frag. 111 Van Groningen.

51 Frag. 68 Schibli. Translation Freeman (1948) modified.

52 Translation Freeman 1948, modified. Schibli (1990) 51–2.

53 Schibli (1990) 63–4, maintains the traditional view that the unveiling was central to the anakaluptêria, but notes “The custom at Greek nuptials to which Pherekydes refers was not, however, the unveiling itself, but the giving of gifts by bridegroom (or friends and relatives) to bride; in Pherekydes’ account this is reflected in the presentation of the robe by Zas to Chthonia” (64).

54 Hesychius, above n. 36.

55 Schibli (1990) 65–6, cites mythical parallels for Zas’s gift of a robe to his bride: the peploi given to Harmonia by Cadmus, together with the notorious necklace (Apollodorus 3.4.2) upon their marriage, and the beautiful peplos that Helen gave to Telemachus, destined for his bride (Odyssey 15.123–8).

56 Seaford (1987) 106–7.

57 Faraone (1991) 22 n.6; Johnston (1999) ch 5.

58 Balthasar Gracian, El Criticón, cited by Babcock (1978) 13–36 (the quotation on p. 13). On opposites in Greek thought and “polar expressions”, see Lloyd (1971) Part 1.

59 Lincoln (1991) 102.

60 Van Gennep (1960) 186–7.