2

Go in the narrow door; because the door is wide and the road is broad leading off to destruction, and many people are going that way. Whereas how narrow the door and how constricted the road leading off to Life, and how few people find it!

—yeshua (jesus) to the crowd on the mount, matthew 7:13–14,

as translated from the original greek

The path of the mystic is not a hobby or an amusement. It is a calling.

As a child, I often found myself plagued by insomnia, my gut clenched with the anxiety brought on by the greatest of mysteries: Who—or what—is God? And how can I get to know him, her, or it? What in the hell is this thing called reality?

From the very beginning, I was trying so hard to just figure out life. I wanted to know what this thing was. What the hell is happening?

Since the beginning of human history—indeed, since the beginning of consciousness—we have been trying to figure this one out.

We are at least aware that we exist … philosophy has figured out this much.

Cogito ergo sum, as is often paraphrased from René Descartes’s seminal work Discourse on the Method. “I think, therefore I am.” Another version of the translation is “I am thinking, therefore I exist,” and this has seemed to reign supreme throughout history as Descartes’s own “first principle of philosophy,” as well as the fundamental basics of consciousness studies.9

We each have a brain; therefore, we receive the reality perceived by the brain. For some, this is enough. However, those called to the Work of the Great Mystery need more. Indeed, it is the Mystery which lures us, like Ariadne’s thread leading us out of the labyrinth of the mundane.

One highly regarded scholar of the Mysteries, Charles R. F. Seymour (known as “the Colonel”), speaks of this inner calling to those who cannot settle for simple answers, those who yearn for a deeper connection with the Source of All Creation: “There is a ‘divine discontent’ that urges one on to seek beyond the skyline where strange roads go down. As a rule it is only the restless soul, who, driven by this strange but divine feeling of discontent, seeks for the Ancient Mysteries …” 10

It is those whose souls grapple with the Mystery of God that are often called to the path of initiation, otherwise known as the Great Work, the pursuit of the philosopher’s stone. Throughout history there have been mystery schools of various fraternities, orders, and grades that have sought—outside of the confines of core religious institutions—an authentic path of transcendence. From the earliest pangs of Neolithic shamanism to the Rites of Mithras, from the pyramids of Egypt to the Temple of Apollo, from the Freemasons to the Theosophical Society, the Great Work has manifested in one way or another throughout history as an enigma. Most typically, the Great Work found itself in the tracks of so-called secret societies, the subject matter of most conspiracy theories.

However, there was always good reason for the rites of these organizations to remain in the dark (oftentimes literally). Partially, it was to avoid persecution. Even before persecution had become the customary reaction of the establishment, though, secrecy was vital to maintaining the integrity of the ritual processes. For an example, turn on the television and watch the news for five minutes. It takes no effort on the part of the populace to take a piece of information and distort it based either on ignorance or political gain. Like mathematics and other sciences, the Mysteries take a lot of training to fully understand. Certain pains were taken by the priests and priestesses of these ancient mystical orders to cover up their ceremonies and methods with symbols and abstractions in order to protect the sanctity of the knowledge they were tasked to carry.

Indeed, this is where the word occult comes from. Contrary to popular opinion, it does not in any way relate to anything “satanic” or “evil.” The term was bastardized by religious fanatics intending to demonize any sort of mystical practice that did not match their own. Occult is derived from the Latin occultus, which means “secret” or “hidden.” All occultism really is or has been is the knowledge of the hidden, such as magic, mysticism, and religion, especially in regard to esotericism (which is often used interchangeably with occultism). Occultism became the common moniker used for ideas regarding the Great Work in the eighteenth century as a reaction to the rationalistic epistemology of the European Enlightenment. Gareth Knight elucidates:

Much portentous nonsense has been written about “occult secrecy,” the “Keys to Power” and the like in past years, mainly to cloak ignorance in the writer, or else for cheap self-aggrandisement. The reason why the Mysteries, which are really the Yoga of the West, are called hidden, and for the few, is because they cannot be explained to outsiders. The barrier is purely one of communication. To try to describe a mystical experience is like trying to describe the scent of a flower, one cannot do it. The best one can do is to tell the enquirer how best he can obtain the particular flower so that he can smell it for himself. If he cannot be bothered to follow your directions or flatly refuses to believe that the flower exists there is nothing one can do about it.11

It is the goal of the initiate, through the vistas of occult, esoteric methodologies, to interpenetrate the unseen in order to unveil the Mysteries of God. So, what exactly is happening when an initiate is “unveiling the Mysteries”?

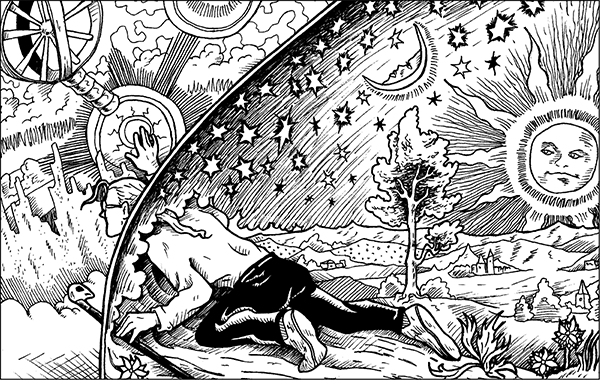

In the year 1888 a very peculiar image made its appearance in French astronomer Camille Flammarion’s L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire. Often referred to generically as the “Flammarion engraving,” it is believed to have been the print of a wood engraving made by either Flammarion himself or an unknown artist. The image shows a man—sometimes noted as a traveler, for he carries a walking cane—kneeling down and stretching his upper body into a breach in the earth and sky horizon, revealing on the other side of this breach another world of cosmic symbols and machinery. In other words, he is moving into the world existing behind—or beyond—the one we currently see with our very eyes.

Flammarion’s caption for this engraving reads, “A missionary of the Middle Ages tells that he has found the point where the sky and the Earth touch …” 12

“Where the sky and Earth touch” would of course be the horizon line. However, there truly is no horizon, is there? You can’t reach it. There is no true point where the sky and earth touch; it is an illusion. But, it is through that illusion, breaching that smokescreen, that the true machinery of the universe reveals itself. This horizon is what is referred to, especially in mystery traditions, as the veil.

The Colonel has discussed at length the process of lifting the veil, or what he calls “the unveiling of the self,” as the prime objective of initiation. The second objective is to raise the veil of the cosmos itself. Paraphrasing G. R. S. Mead, Seymour writes, “To raise it man has to transcend the limits of individuality, to break the bonds of death, and so become conscious of immortality. To raise the veil is to see Nature as she is, and not as she appears to be.” 13 He makes a point to say no mortal human has yet achieved this state of being. However, we see its echoes in the legends and mythologies of our world history, in the Christ of Christianity, White Buffalo Calf Woman of the Lakota, Horus of Egypt, Muhammed of Islam, Elijah of Judaism, Siddhartha of Buddhism, Pachakuteq of the Inca, the avatars of Vishnu in Hinduism, and so on and so forth. There are certain figures in every spiritual tradition across the planet that have some sort of story representing the human’s reach for transcendence, for breaching the veil between earth and sky.

Somewhere engrained in our consciousness, as a collective, we obviously strive for a touchpoint with the unknown. We express this in a variety of ways but most generally through our search for knowledge (science) and our search for beauty (art). However, there are those who dare to push beyond even those limitations, to the fringes of consciousness, that horizon which separates the known from the unknown, the earth from the sky.

This is the mystic path, the strange road that leads beyond the horizon. Lifting the veil is the first task.

Out of the Cave

Plato, the father of Western philosophy, wrote a series of dialogues between himself and his teacher Socrates called Republic. Written sometime around 380 BCE, Republic was centered on defining an ideal society through character, justice, and the education of the soul. In book 7 of the text, Socrates points out that the aim of education is to change the desires of the soul, as outlined in one of the more famous parables in philosophy, popularly called the “Allegory of the Cave.”

Socrates introduces the allegory to show how the lack of education can hinder civilization and then begins to metaphorically describe humanity as beings who live in a deep, underground cave. These beings have been in this underground dwelling since childhood, fixed in one place their whole lives, shackled by the neck and limbs so that they are unable to move and can only face one direction within the cave. They live their entire lives bound, only able to look upon this one wall. And upon this wall, shapes move about, images go to and fro, and they speak to and interact with those images, catalogue those images as they observe them, as those images are the only reality which they know.

But then for some reason, one of those bound beings is able to loosen their shackles and move their head. Imagine this liberated individual is then able to look around the cave—other than that one wall—and see a very disturbing thing: that the images on the wall that they thought were reality were actually just shadows cast by a great fire behind the shackled humans, one they could not see because of their bonds. This whole time what they thought was real was nothing but two-dimensional shadows cast by objects and instruments controlled by a company of puppeteers. Socrates then goes on to say, “Consider, then, what being released from their bonds and cured of their ignorance would naturally be like if something like this came to pass…. [H]e’d be pained and dazzled and unable to see the things whose shadows he’d seen before. What do you think he’d say, if we told him that what he’d seen before was inconsequential, but that now—because he is a bit closer to the things that are and is turned towards things that are more—he sees more correctly?” 14

Imagine the trauma induced by suddenly seeing and knowing the truth! And if that human decided to investigate further, to explore the cave, they would eventually be led up a path which would take them to the surface, where they would be temporarily blinded by the great light of the sun for having lived their entire life in darkness. Imagine the shock of this whole new world about them, seemingly unlimited, strange, beautiful, and terrible.

But why do we start out living in darkness, shackled in the cave? Why are we born shrouded in the veil upon incarnation?

To the ancient Greeks, the river Lethe was the answer to this question. Upon death and journeying to their final resting place in the underworld, a soul was required to drink from one of five rivers, namely the waters of Lethe. Lethe literally means “forgetfulness” or “concealment.” It was believed that a soul must forget their previous life before being reincarnated into a new one.

Whether or not you believe in reincarnation is irrelevant. The myths of old were the compass through which the ancient thinkers could navigate the perplexities of consciousness. It is doubtful they were ever taken literally, but the characters and places within the myths were symbols used to explore the mysteries of phenomena. According to mythologist Joseph Campbell, a myth is “the secret opening through which the inexhaustible energies of the cosmos pour into human cultural manifestation.” 15 Myths are symbols that the psyche produces subconsciously, not through deliberate manufacturing. They keep us in touch with our origins, which are “secret,” concealed.

We can see that the ancient Greeks had this notion of a concealed origin, a connection to the source of being that was disrupted or forgotten. The memory of our origin eludes us. Occasionally, it seems, there is an individual who claims to have refused libation from the River of Forgetfulness, but they are few and far between, and their story can prove quite nebulous at times. For the most part, we all share this commonality, even those who don’t at least share the commonality of the underworld itself, as death waits for us all.

So, we have the great concealer of the past—the river Lethe—and the great concealer of the future—death. What then of the present? Concealed in the past and future, some say the present is the clear point of immediate attention. However, it cannot be entirely that clear, can it? If it were, why would we be so confused? Why would we have so much hate, fear, and bewilderment, which have together cascaded into a societal landslide of near-inevitable extinction for our species?

The Toltec civilization from Mesoamerica proposes another scenario to give some context to our present plight. Don Miguel Ruiz, a Toltec nagual (shaman), discusses the concept called the mitote (mih-TOH-tay), a condition of consciousness that keeps us trapped in a perpetual state of concealment. He likens it to the Hindu concept of maya, an illusion, which is really what reality is.16 The Aboriginal Australians have a similar concept, that life is really a dream. It is a state of being that we are somehow convinced is real, but it really is not. Ruiz writes,

We live in a fog that is not even real. This fog is a dream, your personal dream of life—what you believe, all the concepts you have about what you are, all the agreements you made with others, with yourself, and even with God.

… It is the personality’s notion of “I am.” Everything you believe about yourself and the world, all the concepts and programming you have in your mind, all are the mitote. We cannot see who we truly are; we cannot see that we are not free.

That is why humans resist life. To be alive is the biggest fear humans have.17

We are all sleepwalkers: the vast majority of humanity is moving about, but we are asleep and unable to see each other, constantly bumping into one another, falling down, and walking into walls. How many times have you made the same mistake over and over again? How many times do you make that same New Year’s resolution but are never able to relinquish your old, unhealthy habits? How many times do you keep ending up in the same shitty, destructive relationship?

It is often stated that we are in a collective state of amnesia. I am more apt to say we are in a collective state of anosognosia. Anosognosia is the brain’s inability to be aware of a major deficit or illness with the body, typically due to physiological damage to certain parts of the brain. Maybe the damage we have done to ourselves through the trauma of history has created a physiological state in which we have become unaware of our own deficits. This might be a more updated model of the Christian concept of “original sin” or an explanation of mitote.

Symbols

We are rarely aware of our own collective sickness, our cultural malaise of anosognosia. The initiate on the path of mysticism awakens from this anosognosia, from the cave of our illusions.

After there has been time for acclimation from this awakening, wouldn’t then that human want to return to the cave, to free their other sisters and brothers who are still imprisoned within their old reality? Also, wouldn’t that liberated human also face difficulty in explaining to their shackled fellows the actual world which exists above them? The prisoners would lack the sufficient language and terminology to be able to comprehend these new things the liberator would be describing. They would be confused and confounded, rejecting the absurdities coming from the liberator’s mouth. They would demonize, and maybe even attempt to kill, the liberator for challenging their preconceived notions. As Socrates explained, “In the knowable realm, the form of the good is the last thing to be seen, and it is reached only with difficulty.” 18

It is because of this difficulty to reach the masses—who are shackled to their shadow puppet show—that a liberator will most often resort to symbols and allegories to speak of the actuality of all things. This is the language of the Great Work used by the mystery schools.

A symbol, put simply, is a concept that represents something other than what it is. Examples of symbols are words, ideas, images, and especially numerals. They are abstractions that convey a whole other reality from how they are materially displayed. The word symbol comes from an ancient Greek custom that was used to bind a group of people together. A slate of burned clay was broken to pieces and each piece given to an individual within that group. When the group convened, the individuals would match (symbollein) together the broken pieces, confirming their legitimacy within that group.

Hence, symbols are like pieces of a vast puzzle that, when put together, give us a great understanding of the universal picture. Mathematics is the primary example of this process. However, in esoteric philosophy there is another set of symbols that convey this universal picture in a different way. Unfortunately, there have been dogmatists throughout the ages who have literalized these symbol sets in the spiritual literature and, from that, tyrannized the religious process into a structure of fundamentalism.

Symbols are not meant to be taken at face value. That defies the very nature of a symbol. Gareth Knight states, “The whole aim of symbolism is its own destruction so that one can get to the reality which it represents.” 19 Like the liberator in the cave, symbolism can, with all hope, communicate to those of us shackled to the illusion a bigger reality that exists around us, which the mitote of the Toltecs blinds us to.

Symbols are the language of mysticism, and that language needs to be learned in order to tread these strange paths.

The biggest mistake one can ever make while undertaking the Great Work is to take the imagery of mysticism literally. As Knight stated, the aim of the symbol is its own demise. One has to get past what the symbol seems to represent (its façade) and understand what lies behind it. Symbols are a system of mathematics that initiates use to decipher the secrets of the Mysteries.

Initiation, the Great Work, engages with these symbols in a conscious way—via ritual—to reach the subconscious recesses of the mind. Each symbol (whether it be a Hebrew letter, the image of a tarot card, an astrological glyph, a mythological figure, an angelic being, etc.) represents a key that unlocks a certain dimension existing within the subconscious of the individual. The subconscious can be likened to encrypted data, and the symbols of the Mysteries have been designed over millennia to be the code that unlocks the information already inside us but that we otherwise do not have access to. We may or may not be consciously aware of this unlocking right away. Often, especially as one moves into higher and deeper levels of initiation, it becomes more difficult to consciously discern and put into words the experience.

Each symbol accounts for a factor within the cosmos, within one’s self. When the mind concentrates upon the symbol, and when it is charged through consistent ceremonial processes, it is able to come into contact with the force behind the symbol. There then is the open portal to establish a channel between the aspirant and the World Soul, the realm behind the veil.

Naturally blinded, we are driven by discontent. That much is true. Using symbolic ceremony, the aim of initiation is to lift the Veil of Mystery surrounding us. It is not a singular operation that only happens once in a person’s life; rather, it is a continuous approach to exploring the reality of both the seen and unseen. As the Colonel relays, “… an initiation into the Mysteries by means of ritual is a long-drawn-out process of self-development, that does not take place in a world of time and space. […] In a genuine initiation few can say where or when or at what moment ‘realisation’ came to them. […] Initio means ‘I begin’, and even the most successful initiation merely means a mental and spiritual process in the soul of the candidate. To this process there is no finality.” 20

With no finality, to be a true Initiate then is to align one’s life with the standard that is required for success in the Great Work.

9. René Descartes, “A Discourse on Method,” Descartes: Philosophical Writings, trans. and ed. Elizabeth Anmscombe and Peter Thomas Geach (New York: MacMillian Publishing, 1971), 31.

10. Charles R. F. Seymour, The Forgotten Mage: The Magical Lectures of Colonel C.R.F. Seymour (Loughborough, Leicestershire, UK: Thoth Publications, 1999), 19.

11. Gareth Knight, A Practical Guide to Qabalistic Symbolism, one-volume edition, vol. 1 (Boston, MA: Weiser Books, 2001), 5.

12. Camille Flammarion, L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire (Paris: Hachette, 1888), ١٦٣.

13. Seymour, Forgotten Mage, 126.

14. Plato, Republic, trans. by G. M. A. Grube (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 1992), 187–88.

15. Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973) 3–4.

16. Miguel Ruiz, The Four Agreements: A Practical Guide to Personal Freedom (San Rafael, CA: Amber-Allen Publishing, 1997), 16–17.

17. Ruiz, The Four Agreements, 16–17.

18. Plato, Republic, 189.

19. Knight, Qabalistic Symbolism, vol. 1, 20–21.

20. Seymour, Forgotten Mage, 21.