The student who is not grounded in the elements cannot understand the advanced teaching.

—dion fortune, the training & work of an initiate

In order to begin work upon the Tree of Life we must first know the world around us, the world of the elements. This means we must first begin an intimate relationship with the tenth Sephirah, in which we consciously reside: Malkuth.

One evening, Autumn and I were getting ready for bed. Like she does sometimes, she pulled a statement out of thin air as if we were already in the midst of a conversation.

“That’s why I love shamanism,” she said pointedly.

“Why’s that?” I asked, immediately trying to find the answer to my own question.

“Because it grounds you. No matter what, it always pulls you back here, in this world, to what’s happening right in front of you.”

She could not have been more correct (as always). Autumn was referencing higher states of being—like the Sephiroth—altered states of consciousness, meditation, and so on. Being teachers in a shamanic tradition (and Autumn is a yoga instructor as well), we have more than our fair share of touchpoints with a wide variety of spiritual seekers and practitioners. More often than not, unfortunately, we see a lot of escapism: seekers addicted to seeking, participants whose heads are so far up in the clouds that they have lost touch with the real world. Some even lose all ability to function in reality.

One of our favorite definitions of shamanism comes from anthropologist and psychiatrist Dr. Roger Walsh from the University of California. Dr. Walsh characterizes shamanism as “a family of traditions whose practitioners focus on voluntarily entering altered states of consciousness in which they experience themselves or their spirit(s) interacting with other entities, often by traveling to other realms, in order to serve their community.” 36

This description is comprehensive, and it acknowledges shamanism as a method of practice—or interaction—rather than a specific religion or spiritual path. In fact, almost any religion on the planet stems from, and comprises a branch of, shamanic practice. These are some examples:

• Shaktism, a shamanic subset of Hinduism

• The Bon of Tibetan Buddhism

• A rebbe, often considered a shamanic rabbi in Judaism

• The Muttaqin of Islam

• Curanderismo of Latin America, a synthesis of indigenous shamanism and Catholicism, part of the lineage to which Autumn and I ascribe

The list goes on and on. Essentially, when going back to the origins of any religious or spiritual path around the world, one will find shamanic roots tied to it. It is humankind’s first spiritual tradition, spanning back to the Paleolithic age, and is often considered the first known profession in the world by anthropologists.

Shamanism has evolved over the centuries, becoming an all-inclusive, cross-cultural paradigm for interacting with the unseen realms. However, the shamanic method is not as “otherworldly” as this definition, and common perception, implies.

We cannot be relieved of the burden of everyday life. Seekers are always looking for something “other,” something beyond the pain of living they currently are unable to liberate themselves from. Rabbi Gershon Winkler, who has taken it upon himself to reconnect with the shamanic roots of Judaism, points out, “The shaman in the Judaic tradition does not rush into a spiritual experience like a famished desert traveler arriving at an oasis. Moses [considered the first Qabalist and shaman of Judaism] is not desperate for a vision because he knows that looking for one often gets in the way of seeing one. When we put all of our energies into seeking we risk not finding, we risk rushing past it.” 37

The problem is, the audacious thirst for spiritual experience is a mode of self-deception, and shamanism (or any legitimate mystery school) does not condone this sort of delusion.

Thus, explains Joan Parisi Wilcox, an initiate of the Paqokuna lineage, “By taking the pulse of the metaphysical, the paqo learns to reveal the condition of the physical.” 38 Paqo is the term for the shamanic priests/healers of the Quechua peoples of Peru. The goal of shamanic practice is to have touchpoints with the otherworld but to bring back the information for healing and renewal in this world, the here and now, the kingdom. Any information gained in the metaphysical that is inapplicable to this world is moot and therefore counterproductive.

Shamanic ceremonies are designed to heal conditions of this world, to bring the soul in contact with the earth and physical senses. From soul retrieval to pagos (offerings or payment to spirits), from animal allies to trance drumming, the elements of shamanic ritual are designed to cement the person in their body and in the acceptance of the material life in which they are now living.

This earthly experience, induced by shamanic ritual practices, reminds the body of its place in space and time. We spend so much of our waking day distracting ourselves from life (via television, internet, jobs, phones, traffic, alcohol, etc.) that when it comes to having a spiritual experience, we often cling to spiritual habits that end up doing the exact same thing these other distractions do: take us away from the present moment.

As an initiate, one should recognize this is actually an affront to God. Malkuth is the full realization of Kether. Why would one want anything other than this experience?

This is why shamanism is so important to a Qabalistic practice: a true shamanic experience thrives on the present moment. It supports the fact that right now—with your aching back, your hungry stomach, your kids banging on the walls, your glasses cracked in the left lens, your neighbor’s barking dog, your dirt-covered floor—that is your spiritual experience, that is your experience of God, of spiritual union with the Source of All Being. Gareth Knight reiterates: “The physical world is the world which should be thoroughly grasped by the soul.… The physical world, in that one has to return to it time and time again, must hold the key for spiritual development. And this development is surely not to be gained in regarding all physical nature as a trap and temptation which must be strenuously denied and put away from one.” 39

In this way, a shamanic practice is much like Zen. Both are based upon the philosophy that the pursuit of the good without the recognition and acceptance of the bad is an illusion. To become more than what you are now is folly, for you are already whole just as you are. Even when you are sick, even when you are depressed, even when you are poor, you are already exactly what you need to be in order to have a vital spiritual experience of union with life and death, for they are two sides of the same coin.

It seems oxymoronic that the goal of these rituals, practices, and philosophies of the Mysteries would be to realize that we do not need all these rituals, practices, and philosophies … but that is exactly how it is. Reality is a paradox. We have a bad habit of not realizing we are already out of Plato’s cave; we need to be constantly reminded. Shamanic ritual pulls you out of the distraction, out of the sleepwalking fog, and opens your eyes to what is truly around you.

Engaging in shamanic ritual, as stated by maestro curandero don Oscar Miro-Quesada, assists us out of the mitote and into a balanced state of consciousness: “Through participation in earth-honoring ceremonies we are able to shift from fear to love, from desire to grateful acceptance of ‘what is,’ and from separation to wholeness.” 40

When we seek answers from someone or something else, we separate ourselves from our own inherent wisdom. Initiation is about empowerment. Shamanic Qabalah should connect us to our own intrinsic wholeness, which allows us to see the beauty in everything, to see God in everything, so that one does not have to stick to flights of fancy in order to feel what most mistake to be “unity.”

Shamans do not travel to other worlds for kicks. They do it, as Dr. Walsh wrote, “to serve their community.” So the practice of trance and altered states of consciousness should not become a staple of the everyday experience, but a rarity to remind the everyman that true divinity and harmony reside in the material world, Malkuth. This is the world we must all participate in. We have a lot of problems in Malkuth: racism, sexism, terrorism, mass-consumerism, environmental destruction, war. We can’t solve them in the clouds. We can only solve them here.

The Pachakuti Mesa

Initiation demands a physical experience; we can only go so far meditating upon images. The key to this lies in tapping into the elemental factors governing Malkuth. Israel Regardie states, “The personality must be harmonised. Every element therein demands equilibration in order that illumination ensuing from the magical work may not produce fanaticism and pathology instead of Adeptship and integrity. Balance is required for the accomplishment of the Great Work.… Therefore, the four grades of Earth, Air, Water and Fire plant the seeds of the microcosmic pentagram, and above them is placed … the Crown of the Spirit, the quintessence, added so that the elemental vehemence may be tempered, to the end that all may work together in balanced disposition.” 41

It is the staple template of most indigenous traditions that the elemental powers of Malkuth are recognized, honored, and culled from as a vital component of spiritual practice. From the medicine wheel of the First Nations people of the Americas to the pentagram of the pagan Celts, the Platonic elemental powers of earth, air, fire, and water are represented as an altar set to be used in some way, shape, or form.

The Western Mystery Tradition has an established practice that has been refined over the centuries to include an altar set that replicates the elemental essences to be channeled and utilized in the Great Work. Known as the primary tools of the magician, the implements are symbols, abstract representations of the elemental powers:

• The pentacle or coin represents earth. Essentially, it is a disc made of wood, copper, or tin inscribed with a five-pointed star—or some other representation of the initiate’s spiritual attainment—and acts as the link between the initiate’s godhead and their life on earth.

• The cup or chalice, of course, represents water. Its function is to contain, to form, being the prime feminine implement in a magical toolset. It is in polarity—and used in conjunction—with the wand, the prime masculine tool. Together, they represent the creative act of reproduction as the womb (cup) and phallus (wand).

• The sword represents air. Its purpose is to defend and banish anything corrupt and defiled in the initiate’s path (magically and metaphorically, of course). The sword also acts a reservoir of strength and inspiration, bringing with it a long-standing tradition of chivalry.

• The wand, finally, is fire. The wand is a physical manifestation of the initiate’s Will. When conjuring an image of a wizard from a story, a magical wand or staff will likely be in the picture. It is the magician’s primary implement.

However accurate these are to portraying the elemental faculties of consciousness, I have always found the shamanic implementation closer to source. The WMT methodology works for many, but for some it generates a layer of abstraction. These tools are symbols, not the elements themselves. For instance, a sword is a symbol for air, but there is a layer of abstraction between sword and air, for there is no direct conceptual relationship between them.

Shamanic symbols, on the other hand, get right to the elemental root, tapping into the elemental matrix of Malkuth itself. In the shamanic context, if one were to represent air, a bird or feather would be sufficient, as these are concepts that have a direct relationship with the element of air. There is little to no layer of abstraction. A most pristine example of this is the mesa framework from the Peruvian-based Pachakuti Mesa Tradition, as developed for the Western world by don Oscar Miro-Quesada.

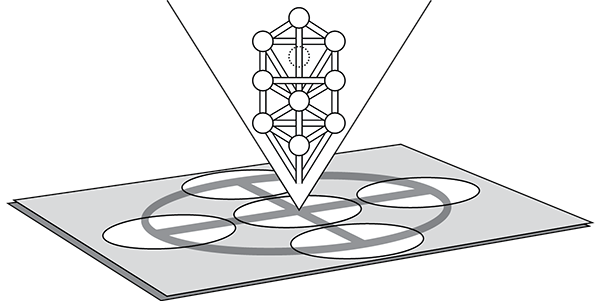

Put simply, a mesa is an altar that is used ritually for healing and connection with the natural (seen and unseen) world. One way to understand the mesa, per author Matthew Magee, is as “a living control panel, co-created by Spirit and the curandero, to become a vehicle for experiencing the ineffable.” 42 The mesa can be understood as a console in order to drive the operations of one’s spiritual work.

The word mesa is a Spanish term meaning “table.” It denotes the typically flat surface area in which a mesa is generally used, sometimes even on top of a table or shelf, but most of the time laid directly upon the ground. The mesa geographically comes from Latin America, most specifically Peru, but can exist in surrounding regions. There are many styles and variations depending on both the region and the individual user. This makes pinpointing a distinct and categorical definition of the mesa challenging to anthropologists. In essence, there is no one way or tradition of the mesa that is the way.

The mesa altar is a created space where religious rites are performed to gain access and connection to whatever source of spiritual awareness one may have (God, Goddess, the Tree of Life, etc.). Anyone can use a mesa; there is no special priest or priestess hierarchy to go through in order to work with it. It is a very personal, individualized tool one uses in their spiritual work.

After many years of being trained under two distinct Peruvian lineages—the Northern Coastal curanderismo and Andean Paqokuna traditions—Miro-Quesada was faced with the task of assimilating these two particular utilizations of the mesa and pondered how to best transcribe its ancient wisdom to the modern world. Through his academic work in psychology, a fascination for the archetypal work of Carl Jung, and his own inner guidance, Miro-Quesada developed the Pachakuti Mesa Tradition as a lucid, well-defined system of shamanic correspondence with the unseen realms. It was designed to articulate a clear transmission of indigenous practice inside a cross-cultural context that could be understood and used in the fast-paced business of the West.

Pachakuti is a Quechua word meaning “world-reversal,” or “turning over the earth.” The ritual schema and practices are specifically fashioned to facilitate an alchemical transformation within the self, and thus the world at large. It draws upon the elemental powers of the universe through ritual objects (called artes) that represent that particular element in its most primal form. So when you are working with the elemental powers, you are working with them kinesthetically, through the primary vehicles of their manifestation in our world.

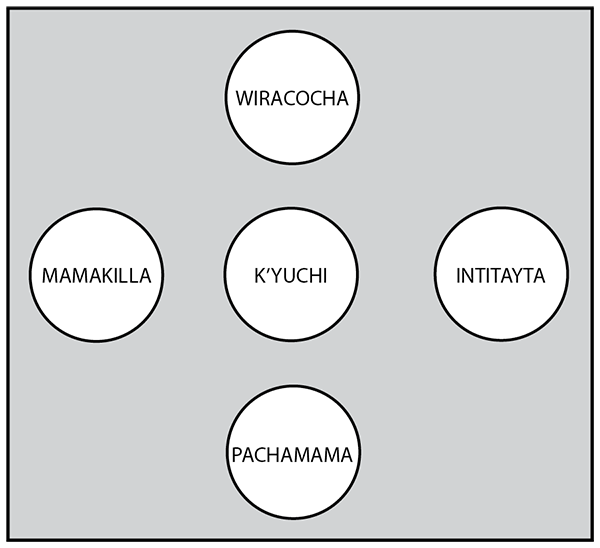

Consider the basic makeup of a Pachakuti mesa and the meaning of its components:

• Pachamama (PAH-cha-MAH-mah): Meaning Mother Earth, Pachamama is the section that resides in the south of the mesa. It represents, of course, the element Earth and material existence. It is where physical healing is called forth and is often connected with the tutelary animal spirit of the boa or anaconda, whose body is always intimate with the earth.

• Mamakilla (MAH-mah-KEE-yah): Meaning “Mother Moon,” Mamakilla resides in the west and epitomizes the emotional realm of being. It evokes the element of water. The tutelary allies are considered the dolphin or whale, as their adept navigation of the ocean personifies what is needed to navigate the deep waters of the emotional psyche.

• Wiracocha (WIHR-ah-KOH-chah): Also known as Great Spirit, Creator, and so on, Wiracocha resides in the north of the mesa and represents the Great Originating Mystery. Embodied by the element of air, it is often exemplified by the tutelary guidance of the eagle or condor, whose flight on the sacred winds personifies the heights we strive for in all spiritual work.

• Inti or Intitayta (IN-tee-TAI-tah): Meaning “Father Sun,” Intitayta resides in the east and characterizes the element of fire. It is the more intellectual realm of being, where the higher mind outmaneuvers our normal brain processes of the day-to-day. The puma and jaguar express these attributes with their clarity of sight and leanness of equilibrium.

• K’yuchi (kooy-EE-chee): K’yuchi is the full spectrum of light we know as the rainbow. It embodies the center of the mesa, the unifying essence of the elemental matrix of Malkuth. Its element is ether, the quintessence material that all things in the material world come from and return to. The llama and alpaca, as animals of service, hold the space of the center as the primary attribute of the self-awakened soul.

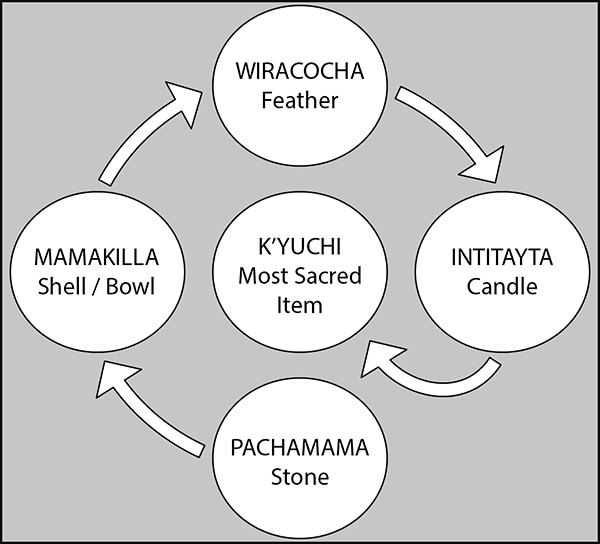

The ritual objects, artes, placed upon the mesa to represent each direction, are archetypal models that manifest the most evocative power that exists within these elemental distinctions:

• Pachamama: Any object that exemplifies the elemental power of allpa (earth element) will do, but most often a stone or crystal is used.

• Mamakilla: Any object that exemplifies the elemental power of unu (water element) will do, but most often a shell or bowl (sometimes filled with water) is used.

• Wiracocha: Any object that exemplifies the elemental power of wayra (air element) will do, but most often a feather is used.

• Intitayta: Any object that exemplifies the elemental power of nina (fire element) will do, but most often a single white candle is used.

• K’yuchi: A person’s most sacred object that exemplifies the harmonious power of t’eqsikallpa (aether element) is used.

The Pachakuti mesa is “awakened” before ritual use by following the logarithmic spiral—found in nature through spiral galaxies, nautilus shells, and so on—throughout the altar space in a clockwise direction, starting from Pachamama in the south and ending at center with K’yuchi.

In activating the altar space by way of this design, the initiate is automatically replicating the act of creation found naturally in Malkuth. The reader is encouraged to initiate this activation through their own intention. However, this is not the only way to understand the elemental matrix as experienced through mesa.

The Cross

In 1970 Princeton University Press published famous psychoanalyst Dr. Carl G. Jung’s final, and most influential, work on alchemy, Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy. In this lengthy tome, Jung unveils that the key to solving the problems plaguing modern man is found in the alchemical process.

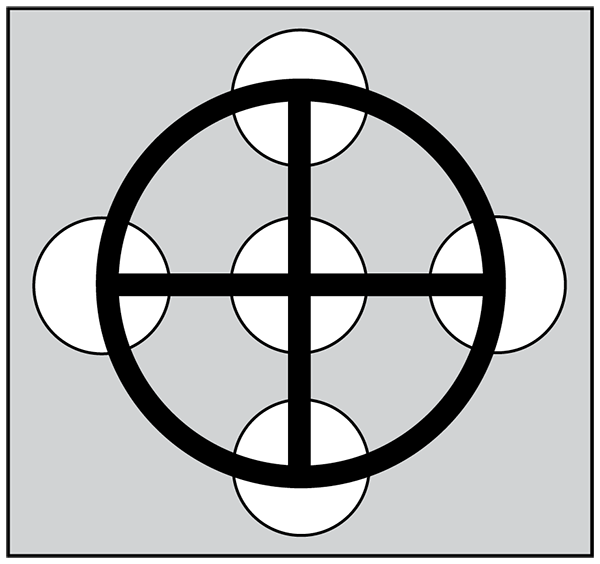

Jung expresses that the primary template of the Great Work can be found in the coniunctio, the unification of opposing elements within Malkuth: “The idea of the cross points beyond the simple antithesis to a double antithesis, i.e., to a quaternio. To the mind of the alchemist this meant primarily the intercrossing elements.… We know that this fastening to a cross denotes a painful state of suspension, or a tearing asunder in the four directions. The alchemists therefore set themselves the task of reconciling the warring elements and reducing them to unity.” 43 So, if we are to experience Jung’s cross of unity on the mesa—the coniunctio—it may look something like this:

Coincidentally, or serendipitously, the elemental placements upon the mesa correspond to the elemental placements on the symbol of the equal-armed cross. This symbol, known sometimes as the “wheel cross” or “Odin’s cross,” is one of the oldest images represented in human history, dating back to the early Bronze Age. According to symbologist Carl Liungman: “In ancient China this sign was associated with thunder, power, energy, head, and respect.… It appears in the earliest systems of writing used by the Egyptians, Hittites, Cretians, Greeks, Etrusians, and Romans. In ancient Greece  signified a sphere or globe. It was also used as a natal chart pattern in ancient astrology. In modern astrology it is the sign for the planet Earth.” 44

signified a sphere or globe. It was also used as a natal chart pattern in ancient astrology. In modern astrology it is the sign for the planet Earth.” 44

This design is also found in Native American medicine wheels, circular stone monuments oriented to the sacred directions. The directions naturally convened in the center as well, creating a sort of equal-armed cross enclosed in a circle similar to the image above.

A spiral represents the circular, more organic or noumenal, way of the natural world; the cross, on the other hand, is indicative of our limited, microcosmic understanding of the world of phenomena. Jung interprets the cross in his alchemical work Mysterium Coniunctionis as a symbol of integration for the human soul:

Man, therefore, who is an image of the great world, and is called the microcosm or little world (as the little world, made after the similitude of its archetype, and compounded of the four elements, is called the great man), has also his heaven and his earth. For the soul and the understanding are his heaven; his body and senses his earth. Therefore, to know the heaven and earth of man, is the same as to have a full and complete knowledge of the whole world and of the things of nature.

The circular arrangement of the elements in the world and in man is symbolized by the mandala and its quaternary [cross] structure.45

Thus, the mesa—or any other sort of similar altar set—is a ritualized reminder that the universe must be experienced through the body. This may seem obvious. But, again, we so often sleepwalk in the mitote fog. To awaken from the slumber and begin the path of initiation into the “higher” realms in the Tree of Life, a full realization and awareness of the senses via the elemental matrix is essential.

It seems we are too often stuck in mystical endeavors; the tendency is to dilute the senses, to move beyond the physical, emotional, and mental states of being to attain the spiritual. But that is not the true mystic approach. Our anosognosia has conditioned us to doubt our own wholeness. Too many of us feel fragmented, incomplete.

By accepting and working with the material aspects of existence in Malkuth, a sort of synthesis is achieved that can allow one to then open a space, or gateway, for which the initiate can begin the Great Work. As the opposites are harmonized, and thus then subsided into union (coniunctio), the pathways of mysticism open into wider vistas and horizons that begin to defy the capacity for language to communicate.

Malkuth depicted in the esoteric traditions is, according to Dion Fortune, “the only Sephirah that is represented as part-coloured instead of a unit, for it is divided into four quarters, which are assigned to the four Elements of Earth, Air, Fire, and Water.” 46 In this differentiation of elements we see the unification of opposites, harmony in duality. These parts, or phases, can also replicate the cycles of our own experience, as also depicted in the calendar year.

Thus, no magical or mystical endeavor bears any fruit if it does not begin and end in Malkuth. If reality is not tangibly affected in some way or another, then spiritual work is useless. This sentiment has been stressed many times by don Oscar Miro-Quesada: “As we begin to engage in this Great Work, living in harmony with the natural order, ceremonially aligning to the pulses, rhythms, and cycles of our sacred earth, our purpose as earthbound souls is revealed.” 47 Therefore, working within the elemental pacha of Malkuth as the foundation of any ritual endeavor ensures a successful process ahead.

36. Roger Walsh, The World of Shamanism: New Vision of an Ancient Tradition (Woodbury, MN: Llewellyn Publications, 2007), 16–17.

37. Winkler, Magic of the Ordinary, 22–23.

38. Joan Parisi Wilcox, Masters of the Living Energy: The Mystical World of the Q’ero in Peru (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2004), 100.

39. Knight, Qabalistic Symbolism, vol. 1, 190.

40. Bonnie Glass-Coffin and don Oscar Miro-Quesada, Lessons in Courage: Peruvian Shamanic Wisdom for Everyday Life (Faber, VA: Rainbow Ridge Books, 2013), 62.

41. Regardie, The Golden Dawn, 29.

42. Magee, Peruvian Shamanism, xvi.

43. Carl G. Jung, Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1989) 421–22.

44. Carl G. Liungman, Dictionary of Symbols (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991), 328.

45. Jung, Mysterium Coniunctionis, 388.

46. Fortune, Mystical Qabalah, 248.

47. Glass-Coffin and Miro-Quesada, Lessons in Courage, 95.