7

Even within duality, the tantrika goes straight to the nondual source, because pure subjectivity always resides immersed within his own nature.

—vasugupta, yoga spandakarika

The first time I ever drank the mescaline-containing psychedelic cactus called San Pedro—or huachuma—my maestro (coincidentally also named Daniel) called me up to his mesa. We were in an all-night healing ceremony called a mesada, in which participants imbibe the San Pedro medicine and receive healings (limpias and levantadas) from the curandero. It is usually held within a lodge space or patio and is most often performed (depending on the region in Peru) in complete darkness.

The medicine of the San Pedro was pulsing in full force through my body, so I struggled a little getting up off the floor. It didn’t help me much that the darkness was pitch, but I managed to shuffle my way to the front of maestro’s mesa. He told me then that the medicine was working strong and flowing through my system. Now, it was time to peak the medicine, for the full result of my healing. With the facilitation of his auxillios (assistants) I would be handed a shell, containing a tobacco infusion, that I would then need to imbibe through each nostril. The infusion was called singado.

As the prospect of this filled me with a heart-pounding terror, he began to pray to and call upon the assistance of San Cipriano.

San Cipriano (Saint Cyprian) was once a bishop of Carthage and is now a symbol of balance in curanderismo, the shamanic art of utilizing San Pedro as a healing sacrament. As I was taught in my curandero lineage, San Cipriano began his path as a magician of Antioch, working the dark arts, and had become one of the more powerful sorcerers in his time. He had in his intention to bring down a pious nun from her servitude of Christ. Her name was Santa Justina. However, his magical attacks were futile against her faith. Through this, Cipriano fell in love with Justina but, seeing as she was a bride of the Church, was inspired to know Christ as well as she. He was received into the priesthood and soon became bishop, and she the head of her convent. Cipriano was even more powerful than most servants of the light because he had experienced the darkness and was able to reconcile the balance of two.

Although curanderismo from Peru is rooted in indigenous folk-healing practices, it is also a fusion of Catholic symbolism and iconography. When the Spanish invaded, the local populations were smart to adopt the Catholic cosmology and incorporate it into their own indigenous spiritual framework. After all, many of the saints, as well as the Holy Trinity, fit almost like perfect puzzle pieces into the Incan pantheon of deities. Anthropologists Donald Joralemon and Douglas Sharon have spent the bulk of their lifetimes studying Northern Coastal Peruvian curanderismo. They express that the amalgamation of native and colonial religions has proven to be a benefit to the healing practice: “Integrating two distinct historical and ethnic traditions—Spanish Catholicism and indigenous animatism—the mesa dialectic provides a code for the problem-solving activities entailed in curing.” 58

Even though Peruvian, and especially Andean, archaeological evidence has always supported such a dialectic, it is perhaps due to this historical integration of traditions that curanderismo iconography is rife with a strong sense of duality. To the Peruvian curanderos, San Cipriano represents the arbiter between Christian and pagan beliefs, light and dark, exemplifying two sides of the same coin that is the curing process in ritual shamanism. Dr. Bonnie Glass-Coffin, professor of anthropology at Utah State University, expresses the important nature of opposites, of duality, in shamanic ceremony: “The binary oppositions of celestial/chthonic, straight/tangled, orderly/chaotic, and culture/nature that permeate cosmological beliefs … [are expressed] in mesa symbolism. Additionally, this emphasis on dualism and opposition seems to influence and reflect the healer’s conceptualization of the harm that threatens his patients.” 59

Maestro had me take in the singado, the tobacco infusion, from the left and then right nostrils. It went down hard, like daggers slicing through my nasal cavity and down my throat. My head swelled, my gut wrenched. He told me the infusion on the left side was taken in order to let go of what was no longer needed in my life. The one on the right side was to call in good fortune for myself. The left for dispatching, the right for raising.

Each side of a person, as well as the mesa (which are reflections of one another), represents certain powers and forces of the universe and psyche that are in opposition and need to come into some sort of harmony. Joraleman and Sharon state, “Curing rituals (including … nasal imbibing of tobacco juice …) activate a dialectical process by which the forces of good and evil in both man and nature are brought into meaningful interaction through the mediation of the middle field. The balance of forces or ‘complementarity of opposites’ achieved through ritual is then symbolically transmitted to the patient.” 60

Life is composed of dualities. It is the resistance and opposition of the dualities that cause suffering and disease, in the curandero paradigm. Additionally, the curandero understands that where there is duality, there is always triality. This is why the curandero’s healing practice is always threefold: first to work one side of these polarities, then the other, and then to integrate a balance between the two. The curandero stands at the crescendo of these two forces, bringing them together to clash, to harmonize. This tug-of-war between dualities is reflected in every ritual process in a curandero’s healing ceremony, as well as in the arrangement of the mesa altar space.

The Campos

There are many different types of mesa out in the world. What has been offered in this book, the Pachakuti Mesa Tradition, is just one of dozens (perhaps hundreds) of mesa traditions across the South American landscape. The mesa—as in all shamanic lineages—is not a dogmatic practice, like the Liturgies of the Catholic Church or the Pillars of Islam. Shamanic traditions are more like family lineages passed on from generation to generation, modified over time as the culture evolves.

I often liken shamanic lineages to that of a family Christmas tradition: grandmother carries her traditions to mother, mother carries it to daughter … A tree is still involved, maybe a Christmas meal, the reading of “The Night Before Christmas,” but it gets changed as each generation modifies it to their own needs. Maybe the tree looks different, the meal switches from turkey to ham, or the reading of “The Night Before Christmas” turns into the viewing of the film The Nightmare Before Christmas. The traditions are still there, just adapted to the needs and desires of the current family unit.

Therefore, there are many different mesa traditions in Peru and in all of Latin America. However, despite the differing iterations, the mesa still accomplishes the same mystical goal: reflecting the practitioner’s cosmology. As such, it is an arena of mediation between the opposing forces of the cosmos. Where the practitioner sits is the unification of these forces; the curandero is the cosmic axis.

It is because of this that most mesas in Peru and abroad include a cross or crucifix gracing the central field. The cross is the ultimate symbol of Christ’s sacrifice, as the curandero must sacrifice of himself in order to serve others. As was discussed earlier, it is also a holistic symbol used the world over in almost every culture. The cross represents the axis mundi, the connection between heaven and earth where the four directions meet.

In the Pachakuti mesa altar, we saw earlier what the cross was conjoining in the mysterium coniunctionis: the elemental powers of Malkuth. But this isn’t the only rendition of this harmonization of opposites in mesa shamanism.

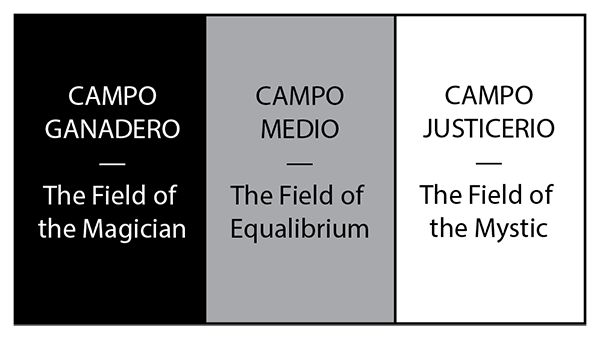

The mesas from the northern coastal Peruvian tradition of huachuma curanderismo work with the elemental powers not from five directional quadrants—as in the Pachakuti mesa—but in three distinct, vertical fields called campos. The campos are divided into the left, middle, and right regions of the mesa. Traditionally, they are set up thus:

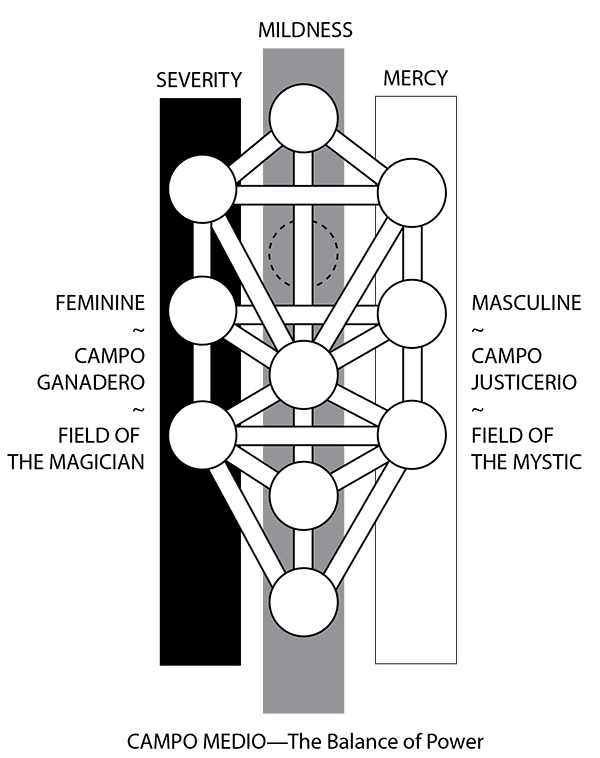

• Campo Ganadero (Left): Known also as the Field of the Sly Dealer or the Field of the Magician, the Campo Ganadero contains artifacts regularly associated with black magic, the underworld, or evil. It is also associated with the past, as well as the feminine. Because this field is associated with darker forces, it is also capable of revealing and thus dispelling them.

• Campo Medio (Middle): Known also as the Middle Field or the Field of Equilibrium, the Campo Medio contains artifacts that stimulate a mediating balance between good and evil, white and dark magic, or masculine and feminine.

• Campo Justicerio (Right): Known also as the Field of the Divine Justice or the Field of the Mystic, the Campo Justicerio contains artifacts normally aligned with white magic and good. This field is also associated with the masculine and bringing forth positive attributes of the future.

The Campo Medio poses an interesting intersection of the dualistic nature of curanderismo, as well as a cosmology paradigm of universal structure. For a curandero, the Campo Medio represents the Middle Road or Middle Way as depicted in North American Indian spirituality. It is ultimate balance, the ability to live and operate the positive and negative faculties of consciousness, to be in two worlds at once. According to curandero don Eduardo CalderÓn,

The Campo Medio is like a judge in this case, or like the needle in a balance, the controlling needle between those two powers, between good and evil. The Campo Medio is where the chiefs, the guardians, those who command, those who govern present themselves, since it is the neutral field—that is, the dividing field between two frontiers where a war can occur over a dispute. That is the place where one has to put all, all, all one’s perseverance so that everything remains well controlled.61

This concept is inherent in the idea that duality is in fact a tripartite operation. There is always the positive, the negative, and then the dialectic between the two. In this case, the Campo Medio is less a field in its own merit than a field of interaction and discourse between the Campo Ganadero and the Campo Justicerio. This interplay actually aligns with the physical processes of curandero healing, which can fit within a three-phase operation of curing:

1. Limpia de Cuy: A ritual cleansing of the body, normally done with artifacts from the Campo Ganadero (left). The goal of the limpia is to extract illness from the individual.

2. Florecimiento: A ritual flowering of the body, normally done with artifacts from the Campo Medio (middle). The goal of the florecimiento is to integrate the holism of the entire curing experience, sending the individual out into the world with good health and well-being.

3. Levantada: A ritual raising of the body, normally done with artifacts from the Campo Justicerio (right). The goal of the levantada is to bring good fortune to the individual in place of the previously extracted illness.

Again, CalderÓn further expresses the need for the integration of these three campos, three fields, within a ritualistic dialectic or discourse to maintain true harmony:

Equilibrium is necessary. If there is no equilibrium between these two forces, between good and evil, the thing changes aspect. It is necessary that equilibrium persist, and be influential.… If evil exists in a fashion that is much more eloquent, stronger, more expressive, more charged with force, good recedes; just as, when there is too much good, evil is separated…. By all means, there has to be this equilibrium, the duality of things so that all is in accord with this road, with the orientation of this equilibrium in the life of man.62

Pillars of Manifestation

The Mysteries have their own architecture. As we see in the cathedrals of Europe, mosques of Arabia, and stupas of Asia, the architecture of a sacred space emulates that which it is trying to invoke and evoke.

Probably the most profound building devoted to worship in the Western esoteric tradition is King Solomon’s Temple from the Old Testament. Many iterations of this temple exist throughout all branches of the Western Mysteries, including (of course) Judaism, Hermeticism, Freemasonry, and even the Egyptian mystery schools. One of the most common depictions mimicked in these variations is the prevailing architectural feature of the two pillars.

The first verifiable account of these pillars, as they are then recounted in all the Mysteries, comes from 1 Kings in the Nevi’im/Old Testament of the Holy Bible. In the passages dedicated to the descriptions of Hiram’s bronze work within the temple, it is depicted: “He set up the columns at the portico of the Great Hall; he set up one column on the right and named it Jachin, and he set up the other column on the left and named it Boaz. Upon the top of the columns there was a lily design. Thus the work of the columns was completed.” 63

The relevance and meaning of the names Jachin and Boaz have created division among Biblical scholars for centuries. Some believe the names are variations of Babylonian or Phoenician deities that were adopted by the Hebrews, while others claim they translate clearly into “To establish in the Lord” and “Strength,” respectively.64 Either way, they communicate to those entering the temple that herein resides the presence of the Almighty.

Western esoteric scholar Manly P. Hall conveys a more naturalistic depiction of the pillars as a representation of polarity within one of the temples of Isis: “The World Virgin is sometimes shown standing between two great pillars—the Jachin and Boaz of Freemasonry—symbolizing the fact that Nature attains productivity by means of polarity. As wisdom personified, Isis stands between the pillars of opposites, demonstrating that understanding is always found at the point of equilibrium and that truth is often crucified between the two thieves of apparent contradiction.” 65

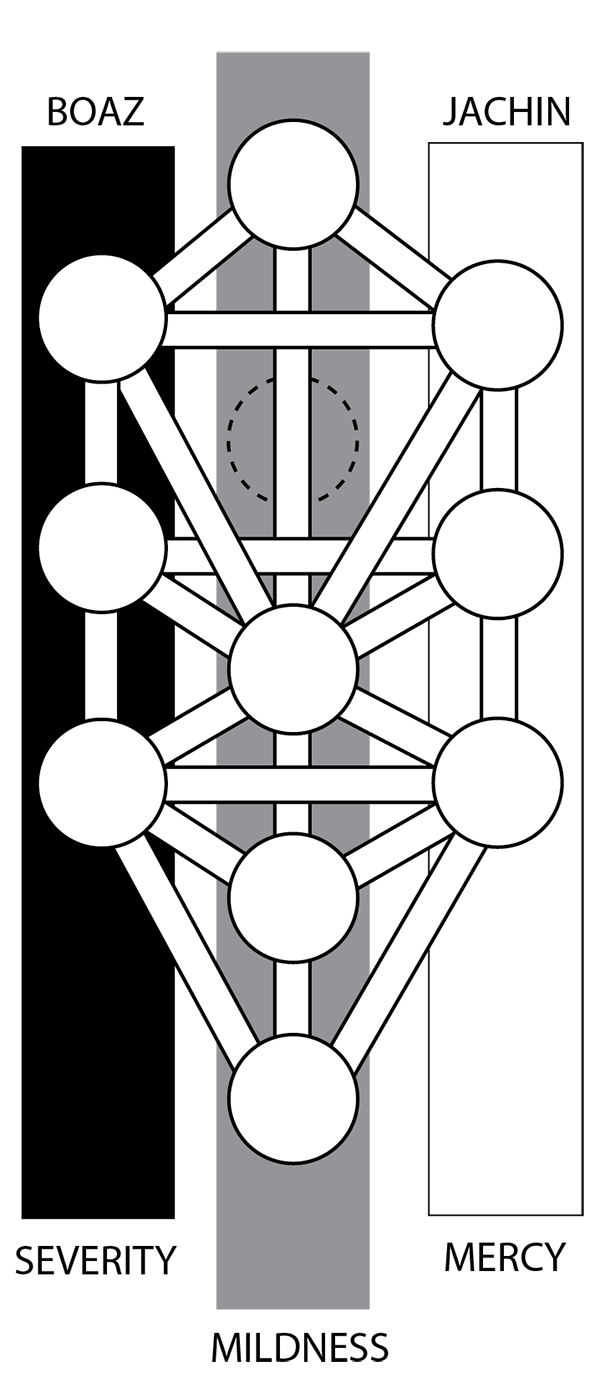

Another way to understand the conscious flow of the Tree of Life, and thus ourselves, is to engage the Sephiroth in terms of what Qabalists call the Pillars of Manifestation. Emulated as a simulation of the pillars in the temples of the Mysteries, the pillars upon the tree provide yet another template for understanding the way the universe works. As Kether came into manifestation, it split into a male aspect (Chokmah) and a female aspect (Binah). Each of these are distributed atop the heads of two columns, generating a vertical alignment of the Sephirah on the Tree of Life. The column on the left is called the Pillar of Severity, and on the right the Pillar of Mercy. In the middle, extending from Kether in the center, is the Pillar of Mildness or Equilibrium. The pillars on the left and right are noted in the Western Mystery Traditions as being representative of the entrance to King Solomon’s Temple, the Pillar of Mildness being the candidate of initiation standing between the two, ready to enter the Mystery.

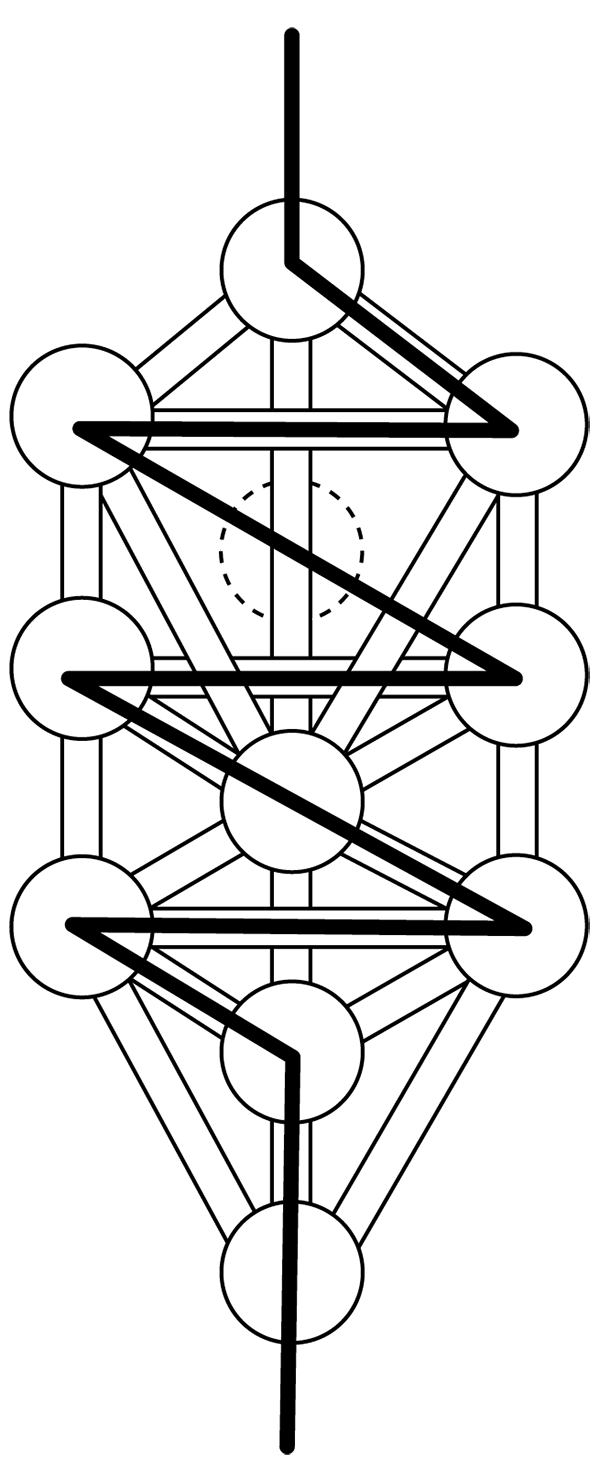

The pillars within the context of the tree represent the paradigm of all creation, that the corporeal world is only manifest through the interaction of opposites. Just as it is shown in the yin-yang symbol from Eastern traditions, the Tree of Life also displays an interaction of the dualistic aspects of the universe in motion. Earlier the Sephiroth were described in their order (1 through 10) upon the tree, which when diagrammed in succession, forms a zig-zag motion across the entirety of the symbol.

This is known as the Lightning Flash, the Descent of Power, or the Flaming Sword in esoteric orders. Following the path of creation, from Kether to Malkuth, from the Unmanifest to the Manifest, we can see that constant interplay between the two poles of duality on the tree. In fact, it is this interplay which creates the mediating presence of the Middle Pillar, which then results in the establishment of corporeality. A further study on the role of these pillars is necessary in order to understand the dialectic of the Pillars of Manifestation.

• Pillar of Severity: Representing the Sephiroth on the left side of the Tree of Life, this pillar signifies the negative pole of universal interaction. It is the feminine side, passive, where the expression of Form is conceptualized into being.

• Pillar of Mercy: Representing the Sephiroth on the right side of the Tree of Life, this pillar signifies the positive pole of universal interaction. It is the masculine side, active, where the expression of Force is conceptualized into being.

• Pillar of Mildness: Representing the Sephiroth in the middle of the Tree of Life, this pillar signifies the equilibrium of the two poles. It is both feminine and masculine and neither at the same time. It is where the expression of consciousness is conceptualized into being.

Force and Form can correlate with the positive and negative poles, respectively. This presents to us a reflection on how interaction with spirit takes place. When descending the tree, all action is first derived in Force before manifesting into Form; therefore, spirit always begins with the idea of something before it becomes something. Conversely, when ascending the tree, all action begins with Form before moving into the thing behind the Form: Force. The universe constantly operates under this paradigm, like a water on seashore ebbing back and forth with the tide, waxing and waning, dancing. This is the cadence of the Sephiroth.

Viewed in this light, it is easy to see the correlations of the curandero mesa in accordance with the three campos. In fact, one could make an exact mapping of the three Pillars of Manifestation with the three campos and would be able to almost flawlessly replicate the operative processes among each triptych.

That these pillars or campos are divided into masculine and feminine attributes should not be taken literally. As clarified before, these are merely symbols to rationalize the positive and negative characteristics of the cosmos. This concept is among one of the toughest for aspiring esotercists to accept, but it also one of the most important to incorporate. Esoteric training is, in theory and practice, the act of making this dual consciousness a single reality. Dion Fortune elucidates that the positive and negative polarities of the Tree exist to create equilibrium:

It is obvious that nothing can be evolved, unfolded, which was not previously involved, infolded. The actual course of evolution follows the track of the Lightning Flash or Flaming Sword, from Kether to Malkuth in the order of development of the Sephiroth previously described; but consciousness descends plane by plane, and only begins to manifest when the polarising Sephiroth are in equilibrium; therefore the modes of consciousness are assigned to the Equilibrating Sephiroth upon the Middle Pillar, but the magical powers are assigned to the opposing Sephiroth, each at the end of the beam of the balance of the pairs of opposites.66

This Middle Way is indeed the modus operandi of shamanic Qabalah and distinguishes the prime differentiation between magic and mysticism. The Great Work can only be completed when the polarizing aspects of consciousness are in equilibrium, harmonized like San Cipriano to highlight the beneficial factors of both the left- and right-hand path.

58. Donald Joraleman and Douglas Sharon, Sorcery and Shamanism: Curanderos and Clients in Northern Peru (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press: 1993), 187.

59. Bonnie Glass-Coffin, The Gift of Life: Female Spirituality and Healing in Northern Peru (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press: 1998), 150.

60. Joraleman and Sharon, Sorcery and Shamanism, 6.

61. Douglas Sharon, Wizard of the Four Winds: A Shaman’s Story, 2nd ed. (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015), 79.

62. Sharon, Wizard of the Four Winds, 175–76.

63. Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1985), 1 Kings 1:31–32.

64. William M. Larson, “Those Mysterious Pillars: Boaz and Jachin,” Pietre-Stones: Review of Freemasonry, accessed April 6, 2018, http://www.freemasons-freemasonry.com/larsonwilliam.html.

65. Manly P. Hall, The Secret Teachings of All Ages: An Encyclopedic Outline of Masonic, Qabbalistic and Rosicrucian Symbolical Philosophy, reader’s ed. (New York: Penguin, 2003), 130.

66. Fortune, Mystical Qabalah, 52.