II

Between the discovery that the Cosmopolitan Stock Brokerage Company was ready to beat me by foul means if the killing handicap of a three-point margin and a point-and-a-half premium didn’t do it, and hints that they didn’t want my business anyhow, I soon made up my mind to go to New York, where I could trade in the office of some member of the New York Stock Exchange. 2.1 I didn’t want any Boston branch, where the quotations had to be telegraphed. I wanted to be close to the original source. I came to New York at the age of 21, bringing with me all I had, twenty-five hundred dollars.

I told you I had ten thousand dollars when I was twenty, and my margin on that Sugar deal was over ten thousand. But I didn’t always win. My plan of trading was sound enough and won oftener than it lost. If I had stuck to it I’d have been right perhaps as often as seven out of ten times. In fact, I always made money when I was sure I was right before I began. What beat me was not having brains enough to stick to my own game—that is, to play the market only when I was satisfied that precedents favored my play. There is a time for all things, but I didn’t know it. And that is precisely what beats so many men in Wall Street who are very far from being in the main sucker class. There is the plain fool, who does the wrong thing at all times everywhere, but there is the Wall Street fool, who thinks he must trade all the time. No man can always have adequate reasons for buying or selling stocks daily—or sufficient knowledge to make his play an intelligent play.

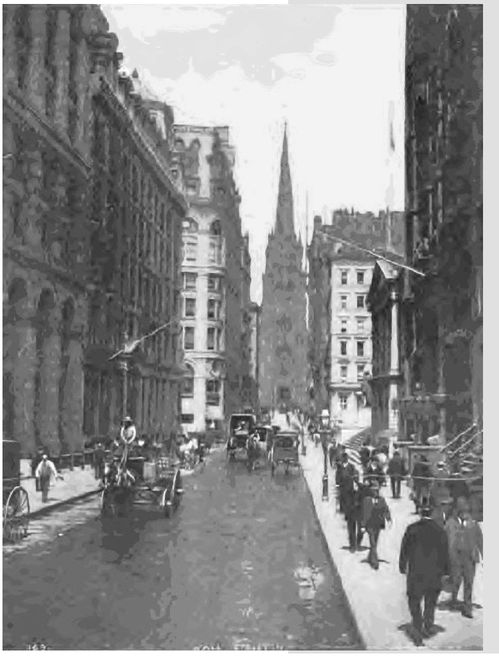

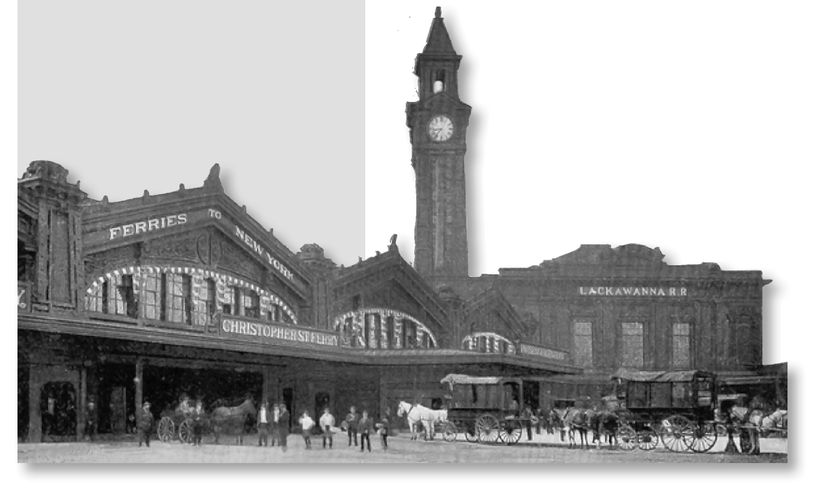

2.1 By the late 1890s, the New York Stock Exchange was already a 100-year-old institution that had survived wars, depressions, fires, and panics. Begun in 1792 by 24 securities brokers who agreed on a minimum commission of 0.25% when trading between each other, it moved progressively from beneath a buttonwood tree on Wall Street, to the Tontine Coffeehouse near Water Street, to the back room of the defunct Courier & Enquirer newspaper, and finally to the grand structure at 12 Broad Street, where Livermore and colleagues would view it with a mixture of respect, awe, distrust, and hopefulness. Although Livermore was not a member of the NYSE and therefore could not trade from the floor, he would have been familiar with the sights, sounds, and smells of the exchange building, which was torn down and rebuilt in its current form in 1903.

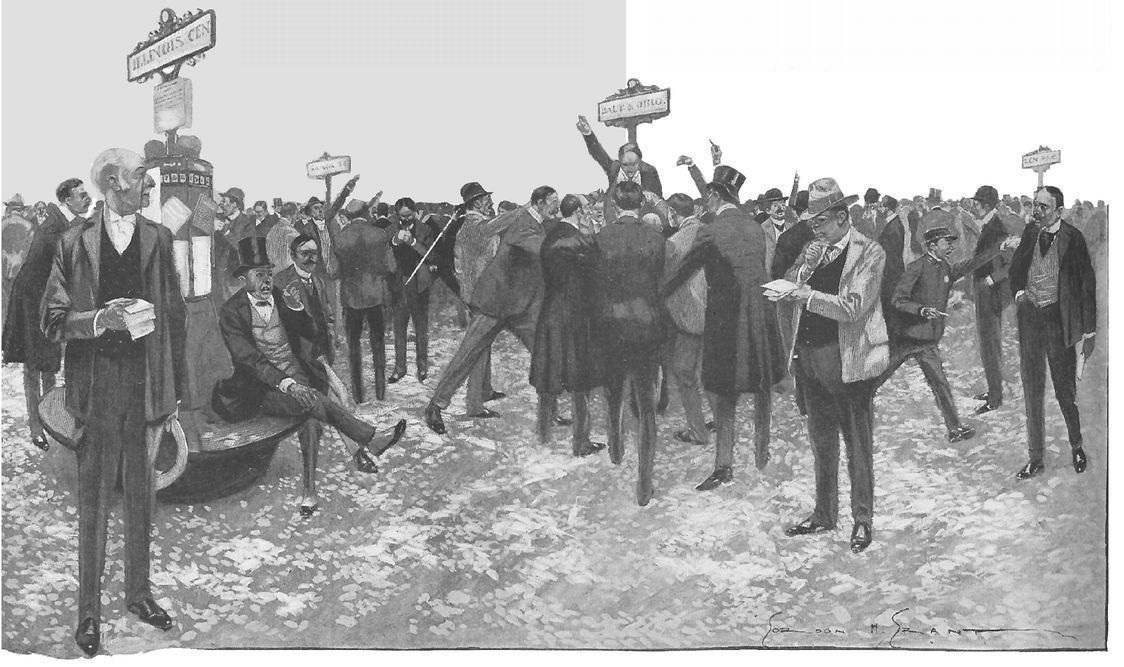

If he entered from Wall Street, the Board Room, with its frenzied crowds, was on the right and the Long Room, filled with telegraphic instruments and telephone equipment, was on the left. Moving into the Board Room, stepping over the littered paper of executed orders, he would see traders grouped around the various stock trading posts. There was a post for the Illinois Central railroad, for instance, and on a board was the price of the previous day’s sales and trading volume. On the far side of the room was a rail that kept the public at bay; clerks and messengers passed messages across it to the floor traders.

Up above, three ornate chandeliers carried 198 electric lamps. An advanced ventilation system provided not only heating and cooling as needed but also perfumed air. Upon arrival in the morning, brokers would ask the superintendent what the day’s bouquet was. At 9:50 A.M., the floor traders were allowed to enter the Board Room. At 10 A.M., the gavel would fall and immediately “a dozen blending thunderstorms break loose,” according to one account. Traders would fill the air with explosive cries, yells, and gesturing hands in a scene that would be familiar to NYSE floor traders today.

12.2 This is one of the pillars of wisdom that Lefevre conveys repeatedly through his depiction of the evolution of Livermore’s development as a trader. Because the market is open six and a half hours a day, five days a week except for holidays, and some stocks are always rising and falling with the news to great fanfare, most new traders think they should have positions open at all times. But Livermore learns to avoid being dragged into the fray by all the commotion and to trade only when he has “sufficient knowledge to make his play an intelligent play.”

2.3 Another of Livermore’s important messages is that traders should never trade to get even or in an effort to buy something in particular, such as a car, because the market tends to punish anger, desperation, and naked greed. Throughout the book, we witness Livermore learning that mastery of the market demands mastery of his own emotions and biases.

I proved it. Whenever I read the tape by the light of experience I made money, but when I made a plain fool play I had to lose. I was no exception, was I? There was the huge quotation board staring me in the face, and the ticker going on, and people trading and watching their tickets turn into cash or into waste paper. Of course I let the craving for excitement get the better of my judgment.

In a bucket shop where your margin is a shoestring you don’t play for long pulls. You are wiped too easily and quickly. The desire for constant action irrespective of underlying conditions is responsible for many losses in Wall Street even among the professionals, who feel that they must take home some money every day, as though they were working for regular wages. I was only a kid, remember. I did not know then what I learned later, what made me fifteen years later, wait two long weeks and see a stock on which I was very bullish go up thirty points before I felt that it was safe to buy it. I was broke and was trying to get back, and I couldn’t afford to play recklessly. I had to be right, and so I waited. That was in 1915. It’s a long story. I’ll tell it later in its proper place. Now let’s go on from where after years of practice at beating them I let the bucket shops take away most of my winnings.

And with my eyes wide open, to boot! And it wasn’t the only period of my life when I did it, either. A stock operator has to fight a lot of expensive enemies within himself.

Anyhow, I came to New York with twenty-five hundred dollars. There were no bucket shops here that a fellow could trust. The Stock Exchange and the police between them had succeeded in closing them up pretty tight.

Besides, I wanted to find a place where the only limit to my trading would be the size of my stake. I didn’t have much of one, but I didn’t expect it to stay little forever. The main thing at the start was to find a place where I wouldn’t have to worry about getting a square deal. So I went to a New York Stock Exchange house that had a branch at home where I knew some of the clerks. They have long since gone out of business. I wasn’t there long, didn’t like one of the partners, and then I went to A. R. Fullerton & Co. Somebody must have told them about my early experiences, because it was not long before they all got to calling me the Boy Trader. I’ve always looked young. It was a handicap in some ways but it compelled me to fight for my own because so many tried to take advantage of my youth. The chaps at the bucket shops seeing what a kid I was, always thought I was a fool for luck and that that was the only reason why I beat them so often.

2.4 Stock exchanges viewed bucket shops as competitors and, during the 1880s and 1890s, tried to run them out of business by blocking their access to price quotes. In the summer of 1887, for instance, Abner Wright, president of the Chicago Board of Trade, threw the equipment of the Postal Telegraph and the Baltimore & Ohio Telegraph companies out of his building for supplying quotes to bucket shops. A few months later, Wright took an ax to some mysterious wires in the basement of the exchange building—inadvertently severing cables to the police and fi re departments.

In response, bucket shops secured legal injunctions to prevent Western Union and the exchanges from removing their ticker equipment. Judges were sympathetic: They saw little difference between brokerages and bucket shops, and wanted to preserve the competition. Many federal and state court rulings between 1883 and 1903 upheld bucket shops’ rights.

To mount a more effective legal fi ght, exchanges decided to try to draw a distinction between stock speculation and stock gambling. Their argument: Trades through brokerages, routed to exchanges and resulting in delivery of equity shares or commodities, produced value by contributing to an orderly market. Whether the trade was made for long-term investment or short-term speculation, the result was a constant stream of quotations on the ticker tape that enhanced liquidity. In comparison, they argued that bucket shop operators were parasites that fed off the trading volume of legitimate brokers while contributing nothing of value.

In 1905, the U.S. Supreme Court finally ruled in favor of the Chicago Board of Trade in a case that determined that exchanges had property rights to data they generated. Exchanges finally were able to cut off the information flow that was bucket shops’ lifeblood. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes supported the exchanges’ separation of speculation and gambling, stating that the former amounted to “serious business contracts for a legitimate and useful purpose” while the latter were “mere wagers.”

Besides the legal challenges, bucket shops were increasingly vilifi ed in the media. A four-part exposé by Merrill Teague in Everybody’s Magazine in 1906 was enough of a threat that infamous bucket shop king C. C. Christie (who was once a legitimate broker and said in 1887 that “the bucket shop is a thief”) defended his operations in the same magazine.

2 Noting that 99% of all trades on the Chicago Board of Trade were settled for cash based on price differences—and not in delivery of grain—Christie charged that the CBOT was the “biggest bucket shop on earth.”

3Teague replied that the primary difference was that “bucket-shoppers always bet against their clients, whereas regular brokers actually buy or sell; that they strive to turn the market against clients so that those who are not losing may be MADE to lose.”

4 All of these accusations are vividly brought to life as we see Livermore evolve as a trader and find the skills necessary to operate effectively on the legitimate exchanges just as the bucket shops fade into history.

Well, it wasn’t six months before I was broke. I was a pretty active trader and had a sort of reputation as a winner. I guess my commissions amounted to something. I ran up my account quite a little, but, of course, in the end I lost. I played carefully; but I had to lose. I’ll tell you the reason: it was my remarkable success in the bucket shops!

I could beat the game my way only in a bucket shop; where I was betting on fluctuations. My tape reading had to do with that exclusively. When I bought the price was there on the quotation board, right in front of me. Even before I bought I knew exactly the price I’d have to pay for my stock. And I always could sell on the instant. I could scalp successfully, because I could move like lightning. I could follow up my luck or cut my loss in a second. Sometimes, for instance, I was certain a stock would move at least a point. Well, I didn’t have to hog it, I could put up a point margin and double my money in a jiffy; or I’d take half a point. On one or two hundred shares a day, that wouldn’t be bad at the end of the month, what?

The practical trouble with that arrangement, of course, was that even if the bucket shop had the resources to stand a big steady loss, they wouldn’t do it. They wouldn’t have a customer around the place who had the bad taste to win all the time.

At all events, what was a perfect system for trading in bucket shops didn’t work in Fullerton’s office. There I was actually buying and selling stocks. The price of Sugar on the tape might be 105 and I could see a three-point drop coming. As a matter of fact, at the very moment the ticker was printing 105 on the tape the real price on the floor of the Exchange might be 104 or 103. By the time my order to sell a thousand shares got to Fullerton’s floor man to execute, the price might be still lower. I couldn’t tell at what price I had put out my thousand shares until I got a report from the clerk. When I surely would have made three thousand on the same transaction in a bucket shop I might not make a cent in a Stock Exchange house. Of course, I have taken an extreme case, but the fact remains that in A. R. Fullerton’s office the tape always talked ancient history to me, as far as my system of trading went, and I didn’t realise it.

And then, too, if my order was fairly big my own sale would tend further to depress the price. In the bucket shop I didn’t have to figure on the effect of my own trading. I lost in New York because the game was altogether different. It was not that I now was playing it legitimately that made me lose, but that I was playing it ignorantly. I have been told that I am a good reader of the tape. But reading the tape like an expert did not save me. I might have made out a great deal better if I had been on the floor myself, a room trader. In a particular crowd perhaps I might have adapted my system to the conditions immediately before me. But, of course, if I had got to operating on such a scale as I do now, for instance, the system would have equally failed me, on account of the effect of my own trading on prices.

In short, I did not know the game of stock speculation. I knew a part of it, a rather important part, which has been very valuable to me at all times. But if with all I had I still lost, what chance does the green outsider have of winning, or, rather, of cashing in?

It didn’t take me long to realise that there was something wrong with my play, but I couldn’t spot the exact trouble. There were times when my system worked beautifully, and then, all of a sudden, nothing but one swat after another. I was only twenty-two, remember; not that I was so stuck on myself that I didn’t want to know just where I was at fault, but that at that age nobody knows much of anything.

The people in the office were very nice to me. I couldn’t plunge as I wanted to because of their margin requirements, but old A. R. Fullerton and the rest of the firm were so kind to me that after six months of active trading I not only lost all I had brought and all that I had made there but I even owed the firm a few hundreds.

2.5 This type of self-examination and inward scolding followed by an epiphany is what has endeared Reminiscences to traders over the decades. In his early years, Livermore regularly finds himself losing money in new ways. Instead of complaining about his bad luck, he studies his personal habits, thought processes, and procedures and determines how he can improve to adjust to new circumstances. His constant effort to mold his methods to fit fresh observations of the economic or structural environment sets him apart from more ordinary traders who rationalize their losses as stemming from changes beyond their control. Lefevre wants the reader to learn that in order to succeed on Wall Street, it is more valuable to be adaptable than to be merely smart or rich.

2.6 The brokerage house of A. R. Fullerton, where Livermore bases his operations early in his career on Wall Street, was in reality the offices of E. F. Hutton & Co. and its predecessor, Harris, Hutton & Company. And “old man” Fullerton, who lent Livermore $500 to take on the bucket shops in St. Louis, was actually Edward Francis Hutton himself. See more about him in Chapter 4.

There I was, a mere kid, who had never before been away from home, flat broke; but I knew there wasn’t anything wrong with me; only with my play. I don’t know whether I make myself plain, but I never lose my temper over the stock market. I never argue with the tape. Getting sore at the market doesn’t get you anywhere.

I was so anxious to resume trading that I didn’t lose a minute, but went to old man Fullerton and said to him, “Say, A. R., lend me five hundred dollars.”

“What for?” says he.

“I’ve got to have some money.”

“What for?” he says again.

“For margin, of course,” I said.

“Five hundred dollars?” he said, and frowned. “You know they’d expect you to keep up a 10 per cent margin, and that means one thousand dollars on one hundred shares. Much better to give you a credit——”

“No,” I said, “I don’t want a credit here. I already owe the firm something. What I want is for you to lend me five hundred dollars so I can go out and get a roll and come back.”

“How are you going to do it?” asked old A. R.

“I’ll go and trade in a bucket shop,” I told him.

“Trade here,” he said.

“No,” I said. “I’m not sure yet I can beat the game in this office, but I am sure I can take money out of the bucket shops. I know that game. I have a notion that I know just where I went wrong here.”

He let me have it, and I went out of that office where the Boy Terror of the Bucket Shops, as they called him, had lost his pile. I couldn’t go back home because the shops there would not take my business. New York was out of the question; there weren’t any doing business at that time. They tell me that in the 90’s Broad Street and New Street were full of them. But there weren’t any when I needed them in my business. So after some thinking I decided to go to St. Louis.

I had heard of two concerns there that did an enormous business all through the Middle West. Their profits must have been huge. They had branch offices in dozens of towns. In fact I had been told that there were no concerns in the East to compare with them for volume of business. They ran openly and the best people traded there without any qualms. A fellow even told me that the owner of one of the concerns was a vice-president of the Chamber of Commerce but that couldn’t have been in St. Louis. At any rate, that is where I went with my five hundred dollars to bring back a stake to use as margin in the office of A. R. Fullerton & Co., members of the New York Stock Exchange.

When I got to St. Louis I went to the hotel, washed up and went out to find the bucket shops. One was the J. G. Dolan Company, and the other was H. S. Teller & Co.

I knew I could beat them. I was going to play dead safe—carefully and conservatively. My one fear was that somebody might recognise me and give me away, because the bucket shops all over the country had heard of the Boy Trader. They are like gambling houses and get all the gossip of the profesh.

Dolan was nearer than Teller, and I went there first. I was hoping I might be allowed to do business a few days before they told me to take my trade somewhere else. I walked in. It was a whopping big place and there must have been at least a couple of hundred people there staring at the quotations. I was glad, because in such a crowd I stood a better chance of being unnoticed. I stood and watched the board and looked them over carefully until I picked out the stock for my initial play.

I looked around and saw the order-clerk at the window where you put down your money and get your ticket. He was looking at me so I walked up to him and asked, “Is this where you trade in cotton and wheat?”

2.7 Bucket shops first appeared in the Midwest in the late 1870s. Initially they were considered only as an incidental evil and had gained no strong foothold.

5 Soon they were booming as bountiful crops in 1879 enriched the region and speculation spread after a return to the gold standard further revived business confidence.

Naive small towns, far from the financial centers of New York and Boston, made easy targets for bucket shops, where “fraud, cheat and swindle are so transparent,” according to an observer at the time. The ticker’s promise of fortune was so strong that it was the subject of a lengthy 1879 editorial in the Chicago Tribune decrying the character of the customers who patronize them:

Boys of larger growth and men, clerks, salesmen, bookkeepers, men in business, hackmen, teamsters, men on salaries, and men employed at day’s work, stone cutters, blacksmiths and workmen of all wages and occupations; students and professors of colleges, reverend divines, dealers in theology, members of Christian Associations, members of societies for the prevention of cruelty to animals, and for the suppression of vice, gentlemen who war on saloons which permit minors to play pool, and teachers of Sunday schools, hard drinkers and temperate men, old men and young men—all, in person or by agent, purchase their 500 or 1,000 or 5,000 or 10,000 bushels, depositing their margins, and confidently hope to have their money back with 100, or even 500 per cent profit.

6These customers were the easy marks for the Midwest bucket shops. So imagine the shop owners’ dismay when a shark of Livermore’s ability entered their parlor. It was like a formidable Las Vegas poker champ sitting down at a card table in the outskirts of Reno. The odds had suddenly turned against them, and Livermore in this chapter bemoans their rude reaction.

2.8 Both of these companies, along with the Cosmopolitan Stock Brokerage Company mentioned earlier, appear to be fictitious stand-ins for real bucket shop operators. The two in St. Louis were most likely C. C. Christie and the Cella Commission Co., both of which had large operations focused on the Midwest.

72.9 Livermore repeatedly refers to the bucket shops with the language of casinos. He complains here that bucket shop managers were on the lookout for him just like dealers in the gambling “profesh,” or profession, make an effort to watch for notorious card counters at the blackjack tables.

2.10 The Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis and Omaha Railway, better known simply as the Omaha, was a popular stock at the time. The company was incorporated in 1880 and operated in Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, Ne braska, and South Dakota. In 1882, control of the Omaha was turned over to the Chicago and North Western rail road. Eventually, in the 1990s, the Omaha was absorbed into the Union Pacific, which survives to this day.

8,

9,

10“Yes, sonny,” says he.

“Can I buy stocks too?”

“You can if you have the cash,” he said.

“Oh, I got that all right, all right,” I said like a boasting boy.

“You have, have you?” he says with a smile.

“How much stock can I buy for one hundred dollars?” I asked, peeved-like.

“One hundred; if you got the hundred.”

“I got the hundred. Yes; and two hundred too!” I told him.

“Oh, my!” he said.

“Just you buy me two hundred shares,” I said sharply.

“Two hundred what?” he asked, serious now. It was business.

I looked at the board again as if to guess wisely and told him, “Two hundred Omaha.”

“All right!” he said. He took my money, counted it and wrote out the ticket.

“What’s your name?” he asked me, and I answered, “Horace Kent.”

He gave me the ticket and I went away and sat down among the customers to wait for the roll to grow. I got quick action and I traded several times that day. On the next day too. In two days I made twenty-eight hundred dollars, and I was hoping they’d let me finish the week out. At the rate I was going, that wouldn’t be so bad. Then I’d tackle the other shop, and if I had similar luck there I’d go back to New York with a wad I could do something with.

On the morning of the third day, when I went to the window, bashful-like, to buy five hundred B. R. T. the clerk said to me, “Say, Mr. Kent, the boss wants to see you.”

I knew the game was up. But I asked him, “What does he want to see me about?”

2.11 The Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT), originally called the Brooklyn Union Elevated Railroad, was formed with $20 million in January 1896, to build and run railroads in the Brooklyn borough of New York. A month later, it took control of the bankrupt Long Island Traction Co. By 1900, it controlled nearly all of the streetcar lines east of Manhattan. Shares traded on the NYSE under the symbol B.

BRT shares were the focus of intense speculative attention during this period, which, based on Livermore’s age of 22, is sometime in 1899. The stock rose rapidly from $35 in early 1898 to above $70 later that year, thanks to buying by ex-governor Roswell Flower (whom we will meet later) and a speculative fever set off by the U.S. war victory over Spain. In March 1899, BRT was the center of a major bull cycle on Wall Street as shares passed $136.

“I don’t know.”

“Where is he?”

“In his private office. Go in that way.” And he pointed to a door.

I went in. Dolan was sitting at his desk. He swung around and said, “Sit down, Livingston.”

He pointed to a chair. My last hope vanished. I don’t know how he discovered who I was; perhaps from the hotel register.

“What do you want to see me about?” I asked him.

“Listen, kid. I ain’t got nothin’ agin yeh, see? Nothin’ at all. See?”

“No, I don’t see,” I said.

He got up from his swivel chair. He was a whopping big guy. He said to me, “Just come over here, Livingston, will yeh?” and he walked to the door. He opened it and then he pointed to the customers in the big room.

“D’ yeh see them?” he asked.

“See what?”

“Them guys. Take a look at ’em, kid. There’s three hundred of ’em! Three hundred suckers! They feed me and my family. See? Three hundred suckers! Then yeh come in, and in two days yeh cop more than I get out of the three hundred in two weeks. That ain’t business, kid—not for me! I ain’t got nothin’ agin yeh. Yer welcome to what ye’ve got. But yeh don’t get any more. There ain’t any here for yeh!”

“Why, I——”

2.12 “Piece of cheese” is another slice of slang from card gambling. It refers to an unwanted card in poker that is destined for the ”muck,” or discard pile. By extension, it was used to refer to an undesirable person.

2.13 Teller was likely the Cella Commission Co., a real bucket shop that Livermore singles out for vengeance. The outfit was run by Louis and Angelo Cella, both of whom were actively involved in horse racing. Cella was based in St. Louis, had recently expanded to the eastern states, and was famous for closing out customer accounts “when they ‘get right’ with the market; that is, when they get on the winning side.” In 1901, when cotton advanced, many of the customers of Cella’s southern branches made a killing at its expense. The trades were closed and the offices abandoned.

11,

12,

132.14 Shares topped out at $137 in April before plunging upon Flower’s death in May. The company ultimately declared bankruptcy in 1919. Its rise and fall was very much like the Internet stocks of the late 1990s, which offered great promise and sold at astronomical multiples of sales when emotions ran high yet ultimately collapsed for lack of consistent earnings.

“That’s all. I seen yeh come in day before yesterday, and I didn’t like yer looks. On the level, I didn’t. I spotted yeh for a ringer. I called in that jackass there”—he pointed to the guilty clerk—“and asked what you’d done; and when he told me I said to him: ‘I don’t like that guy’s looks. He’s a ringer!’ And that piece of cheese says:

‘Ringer my eye, boss! His name is Horace Kent, and he’s a rah-rah boy playing at being used to long pants. He’s all right!’ Well, I let him have his way. That blankety-blank cost me twenty-eight hundred dollars. I don’t grudge it yeh, my boy. But the safe is locked for yeh.”

“Look here—” I began.

“You look here, Livingston,” he said. “I’ve heard all about yeh. I make my money coppering suckers’ bets, and yeh don’t belong here. I aim to be a sport and yer welcome to what yeh pried off ’n us. But more of that would make me a sucker, now that I know who yeh are. So toddle along, sonny!”

I left Dolan’s place with my twenty-eight hundred dollars’ profit. Teller’s place was in the same block. I had found out that Teller was a very rich man who also ran up a lot of pool rooms.

I decided to go to his bucket shop. I wondered whether it would be wise to start moderately and work up to a thousand shares or to begin with a plunge, on the theory that I might not be able to trade more than one day. They get wise mighty quick when they’re losing and I did want to buy one thousand B. R. T.

I was sure I could take four or five points out of it. But if they got suspicious or if too many customers were long of that stock they might not let me trade at all. I thought perhaps I’d better scatter my trades at first and begin small.

It wasn’t as big a place as Dolan’s, but the fixtures were nicer and evidently the crowd was of a better class. This suited me down to the ground and I decided to buy my one thousand B. R. T. So I stepped up to the proper window and said to the clerk, “I’d like to buy some B. R. T. What’s the limit?”

“There’s no limit,” said the clerk. “You can buy all you please—if you’ve got the money.”

“Buy fifteen hundred shares,” I says, and took my roll from my pocket while the clerk starts to write the ticket.

Then I saw a red-headed man just shove that clerk away from the counter. He leaned across and said to me, “Say, Livingston, you go back to Dolan’s. We don’t want your business.”

“Wait until I get my ticket,” I said. “I just bought a little B. R. T.”

“You get no ticket here,” he said. By this time other clerks had got behind him and were looking at me. “Don’t ever come here to trade. We don’t take your business. Understand?”

There was no sense in getting mad or trying to argue, so I went back to the hotel, paid my bill and took the first train back to New York. It was tough. I wanted to take back some real money and that Teller wouldn’t let me make even one trade.

I got back to New York, paid Fullerton his five hundred, and started trading again with the St. Louis money. I had good and bad spells, but I was doing better than breaking even. After all, I didn’t have much to unlearn; only to grasp the one fact that there was more to the game of stock speculation than I had considered before I went to Fullerton’s office to trade. I was like one of those puzzle fans, doing the crossword puzzles in the Sunday supplement.

He isn’t satisfied until he gets it. Well, I certainly wanted to find the solution to my puzzle. I thought I was done with trading in bucket shops. But I was mistaken.

About a couple of months after I got back to New York an old jigger came into Fullerton’s office. He knew A. R. Somebody said they’d once owned a string of race horses together. It was plain he’d seen better days. I was introduced to old McDevitt. He was telling the crowd about a bunch of Western racetrack crooks who had just pulled off some skin game out in St. Louis. The head devil, he said, was a pool-room owner by the name of Teller.

“What Teller?” I asked him.

“Hi Teller; H. S. Teller.”

2.15 The action in this chapter takes place around 1900, but historians say the fi rst crossword puzzle did not appear in a newspaper until December 1913. It was created by journalist Arthur Wynne of Liverpool, England, and it appeared on a Sunday in the New York World. Crosswords became a regular weekly feature in the World, and later the practice was picked up by the Boston Globe in 1917. Early crosswords were diamond shaped and had no internal black squares. Other newspapers began to run crosswords as they became a craze in the early 1920s, and that is when they took on their familiar rectangular shape and the use of black squares began.

Livermore refers positively to the time and effort it took to solve a crossword, but puzzles had many detractors, who considered them a silly fad. In an editorial titled “A Familiar Form of Madness,” the New York Times complained of the “sinful waste in the utterly futile finding of words the letters of which will fit into a prearranged pattern, more or less complex. This is not a game at all, and it hardly can be called a sport; it merely is a new utilization of leisure by those for whom it otherwise would be empty and tedious. They get nothing out of it except a primitive form of mental exercise, and success or failure in any given attempt is equally irrelevant to mental development.

14 By 1942, the Times had finally determined crosswords were not a major threat to Western culture after all, and launched its own puzzle, which has become the pastime’s benchmark.

WEEKLY BANK STATEMENT-NEW YORK CITY.

2.16 The cost and availability of credit have always been important to general market conditions because of the way they impact the capacity for corporate expansion and margin borrowing. Just as investors today watch the Federal Reserve’s statements for insight into the movement of interest rates, in Livermore’s era, prior to the establishment of the Federal Reserve System, traders would examine the weekly bank statement (see illustration) from the New York Clearinghouse. The NYCH was a member-owned association responsible for clearing checks between banks and brokers that offered assistance during financial panics; it also performed banking examinations as a sort of industry-run regulatory body.

Since the United States was on the gold standard at this time, credit conditions were regional in nature as gold bullion would need to be physically transported between banks. Thus, credit conditions for the NYSE were largely determined by the level of gold reserves within the New York area.

The statement Livermore is referring to was issued by the NYCH once a week, on Saturday at noon. If Saturday was a holiday, it was issued at 3 P.M. on Friday. The statement gave the conditions of all member banks; provided the weekly average amounts of loans, gold reserves, currency notes, and deposits; and listed gains and losses in each item compared to the previous week. Similar bank statements were made in other large cities, but the New York statement was taken as a proxy for the credit conditions of the country due to the city’s importance as a financial center. The Bank of England issued a similar statement on Thursdays, which was also closely watched.

“I know that bird,” I said.

“He’s no good,” said McDevitt.

“He’s worse than that,” I said, “and I have a little matter to settle with him.”

“Meaning how?”

“The only way I can hit any of these short sports is through their pocketbook. I can’t touch him in St. Louis just now, but some day I will.” And I told McDevitt my grievance.

“Well,” says old Mac, “he tried to connect here in New York and couldn’t make it, so he’s opened a place in Hoboken. The word’s gone out that there is no limit to the play and that the house roll has got the Rock of Gibraltar faded to the shadow of a bantam flea.”

“What sort of a place?” I thought he meant pool room.

“Bucket shop,” said McDevitt.

“Are you sure it’s open?”

“Yes; I’ve seen several fellows who’ve told me about it.”

“That’s only hearsay,” I said. “Can you find out positively if it’s running, and also how heavy they’ll really let a man trade?”

“Sure, sonny,” said McDevitt. “I’ll go myself tomorrow morning, and come back here and tell you.”

He did. It seems Teller was already doing a big business and would take all he could get. This was on a Friday. The market had been going up all that week—this was twenty years ago, remember—and it was a cinch the bank statement on Saturday would show a big decrease in the surplus reserve.

That would give the conventional excuse to the big room traders to jump on the market and try to shake out some of the weak commission-house accounts. There would be the usual reactions in the last half hour of the trading, particularly in stocks in which the public had been the most active. Those, of course, also would be the very stocks that Teller’s customers would be most heavily long of, and the shop might be glad to see some short selling in them. There is nothing so nice as catching the suckers both ways; and nothing so easy—with one-point margins.

Livermore would have likely seen the initial results of the statement stream over the ticker. Not all the details would have been available, but he would have been able to see the total weekly changes in the various categories. The full statement was later copied by newspapers and financial magazines.

15,

16That Saturday morning I chased over to Hoboken to the Teller place. They had fitted up a big customers’ room with a dandy quotation board and a full force of clerks and a special policeman in gray. There were about twenty-five customers.

I got talking to the manager. He asked me what he could do for me and I told him nothing; that a fellow could make much more money at the track on account of the odds and the freedom to bet your whole roll and stand to win thousands in minutes instead of piking for chicken feed in stocks and having to wait days, perhaps. He began to tell me how much safer the stock-market game was, and how much some of their customers made—you’d have sworn it was a regular broker who actually bought and sold your stocks on the Exchange—and how if a man only traded heavy he could make enough to satisfy anybody. He must have thought I was headed for some pool room and he wanted a whack at my roll before the ponies nibbled it away, for he said I ought to hurry up as the market closed at twelve o’clock on Saturdays. That would leave me free to devote the entire afternoon to other pursuits. I might have a bigger roll to carry to the track with me—if I picked the right stocks.

2.17 Hoboken, New Jersey, was a thriving port city in the late 1890s and early 1900s, situated directly across the Hudson River from Manhattan, with major facilities for transatlantic shipping lines, such as Holland America and North American Lloyd. Most American troops shipping out to serve in World War I embarked for Europe there, giving rise to the hopeful phrase credited to General Pershing, “Heaven, Hell or Hoboken by Christmas.” Leading financiers, such as John Jacob Astor, William Vanderbilt, and Jay Gould, entertained clients at Duke’s House restaurant at the Hoboken ferry dock before it burned down in 1905.

I looked as if I didn’t believe him, and he kept on buzzing me. I was watching the clock. At 11:15 I said, “All right,” and I began to give him selling orders in various stocks. I put up two thousand dollars in cash, and he was very glad to get it. He told me he thought I’d make a lot of money and hoped I’d come in often.

It happened just as I figured. The traders hammered the stocks in which they figured they would uncover the most stops, and, sure enough, prices slid off. I closed out my trades just before the rally of the last five minutes on the usual traders’ covering.

There was fifty-one hundred dollars coming to me. I went to cash in.

“I am glad I dropped in,” I said to the manager, and gave him my tickets.

“Say,” he says to me, “I can’t give you all of it. I wasn’t looking for such a run. I’ll have it here for you Monday morning, sure as blazes.”

“All right. But first I’ll take all you have in the house,” I said.

“You’ve got to let me pay off the little fellows,” he said. “I’ll give you back what you put up, and anything that’s left. Wait till I cash the other tickets.” So I waited while he paid off the other winners. Oh, So I waited while he paid off the other winners. Oh, I knew my money was safe. Teller wouldn’t welsh with the office doing such a good business. And if he did, what else could I do better than to take all he had then and there? I got my own two thousand dollars and about eight hundred dollars besides, which was all he had in the office. I told him I’d be there Monday morning. He swore the money would be waiting for me.

I got to Hoboken a little before twelve on onday.

I saw a fellow talking to the manager that I had seen in the St. Louis office the day Teller told me to go back to Dolan. I knew at once that the manager had telegraphed to the home office and they’d sent up one of their men to investigate the story. Crooks don’t trust anybody.

“I came for the balance of my money,” I said to the manager.

“Is this the man?” asked the St. Louis chap.

“Yes,” said the manager, and took a bunch of yellow backs from his pocket.

“Hold on!” said the St. Louis fellow to him and then turns to me, “Say, Livingston, didn’t we tell you we didn’t want your business?”

“Give me my money first,” I said to the manager, and he forked over two thousands, four five-hundreds and three hundreds.

“What did you say?” I said to St. Louis.

“We told you we didn’t want you to trade in our place.”

“Yes,” I said; “that’s why I came.”

“Well, don’t come any more. Keep away!” he snarled at me. The private policeman in gray came over, casual-like. St. Louis shook his fist at the manager and yelled: “You ought to’ve known better, you poor boob, than to let this guy get into you. He’s Livingston. You had your orders.”

2.18 Gold notes or gold certificates were a paper currency redeemable for gold coin and issued until the early 1930s. Known as “yellow backs,” they contrasted with greenbacks or United States notes, which were a fiat currency not transferable into precious metal on demand.

2.19 Exchanges’ efforts to destroy the bucket shops culminated in a landmark 1909 federal law banning them in the District of Columbia. This photo shows a crowd gathering outside the Mallers Building in Chicago during a police raid of a bucket shop in 1905. Sights like these would become increasingly common throughout the country in the years that followed. Justice Department special agent Bruce Bielaski used this new authority, along with evidence collected during the exchanges’ three-decade campaign, to launch the final, fatal indictment of bucket shops. Over 10 weeks in early 1910, Bielaski sent investigators out to seven cities to examine operations of bucket shops with offices in Washington, D.C. The Justice Department noted that “substantially every bucket shop in the country has been put out of business as a result of this crusade.” By the end of 1915, William Van Antwerp of the New York Stock Exchange declared the bucket shop dead.

17With the bucket shops closed, new business poured into the exchanges. In April 1916, the New York Times wrote of a “remarkable increase in the odd lot business” as thousands of old bucket shop customers, “practically all of whom were small speculators, have opened accounts with branches of Stock Exchange houses.”

18

“Listen, you,” I said to the St. Louis man. “This isn’t St. Louis. You can’t pull off any trick here, like your boss did with Belfast Boy.”

“You keep away from this office! You can’t trade here!” he yells.

“If I can’t trade here nobody else is going to,” I told him. “You can’t get away with that sort of stuff here.”

Well, St. Louis changed his tune at once.

“Look here, old boy,” he said, all fussed up, “do us a favor. Be reasonable! You know we can’t stand this every day. The old man’s going to hit the ceiling when he hears who it was. Have a heart, Livingston!”

“I’ll go easy,” I promised.

“Listen to reason, won’t you? For the love of Pete, keep away! Give us a chance to get a good start. We’re new here. Will you?”

“I don’t want any of this high-and-mighty business the next time I come,” I said, and left him talking to the manager at the rate of a million a minute. I’d got some money out of them for the way they treated me in St. Louis. There wasn’t any sense in my getting hot or trying to close them up. I went back to Fullerton’s office and told McDevitt what had happened. Then I told him that if it was agreeable to him I’d like to have him go to Teller’s place and begin trading in twenty or thirty share lots, to get them used to him. Then, the moment I saw a good chance to clean up big, I’d telephone him and he could plunge.

I gave McDevitt a thousand dollars and he went to Hoboken and did as I told him. He got to be one of the regulars. Then one day when I thought I saw a break impending I slipped Mac the word and he sold all they’d let him. I cleared twenty-eight hundred dollars that day, after giving Mac his rake-off and paying expenses, and I suspect Mac put down a little bet of his own besides. Less than a month after that, Teller closed his Hoboken branch. The police got busy. And, anyhow, it didn’t pay, though I only traded there twice. We ran into a crazy bull market when stocks didn’t react enough to wipe out even the one-point margins, and, of course, all the customers were bulls and winning and pyramiding. No end of bucket shops busted all over the ountry.

Their game has changed. Trading in the old-fashioned bucket shop had some decided advantages over speculating in a reputable broker’s office. For one thing, the automatic closing out of your trade when the margin reached the exhaustion point was the best kind of stop-loss order. You couldn’t get stung for more than you had put up, and there was no danger of rotten execution of orders, and so on. In New York the shops never were as liberal with their patrons as I’ve heard they were in the West. Here they used to limit the possible profit on certain stocks of the football order to two points. Sug ar and Tennessee Coal and Iron were among these.

No matter if they moved ten points in ten minutes you could only make two on one ticket. They figured that otherwise the customer was getting too big odds; he stood to lose one dollar and to make ten. And then there were times when all the shops, including the biggest, refused to take orders on certain stocks. In 1900, on the day before Election Day, when it was a foregone conclusion that McKinley would win, not a shop in the land let its customers buy stocks. The election odds were 3 to 1 on McKinley. By buying stocks on Monday you stood to make from three to six points or more. A man could bet on Bryan and buy stocks and make sure money.

The bucket shops refused orders that day.

If it hadn’t been for their refusing to take my business I never would have stopped trading in them. And then I never would have learned that there was much more to the game of stock speculation than to play for fluctuations of a few points.

Better known as TCI, the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Co. was a major U.S. steel manufacturer with assets in coal and iron ore mining as well as railways. The company was one of 12 that comprised the first Dow Jones Industrial Average index in 1896. It was a direct competitor to J. P. Morgan’s massive United States Steel Corporation until he was able to secure control during the turmoil surrounding the Panic of 1907. At the time, TCI owned an estimated 800 million tons of iron ore and 2 billion tons of coal.

19

William Jennings Bryan ran again unsuccessfully as a Democrat in the 1900 presidential election. Much of the same dynamic that played out in the 1896 contest between Bryan and William McKinley recurred. The economy was vibrant heading into the election. And America had won the brief Spanish-American War of 1898.

Bryan again ran on a “free silver” platform, but the message was not as popular as in 1896 due to the discovery of new gold deposits. Between 1900 and 1908, worldwide annual gold production surged from 425 tons to 736 tons, easing global monetary conditions by allowing more currency into circulation.

20 Gold proponents, who favored a “sound money” policy, cast Bryan’s populist rhetoric as encouraging repudiation against the wealthy classes at best and full anarchy at worst.

Although Bryan’s dream to restore the dollar to the pre-Civil War standard of convertibility into gold or silver never came to fruition, his desire to free the dollar from the constraints of gold was realized upon President Richard Nixon’s order in 1971. Meanwhile, inflation raged: A dollar from 1900 would be worth $25.19 in 2009.

Livermore is referring in this passage to the belief that a McKinley win would be good for business conditions and great for stocks; a Bryan election would be good only for those wagering on his long-shot odds of victory. Bucket shops did best in volatile but trendless markets and worst in one-way markets, so they closed when the odds lined up against them.

Because most bucket shop operators refused to do business with Livermore and at any rate were fading from the scene, he next determines he must quit day-trading at them for short-term gain and learn how to use his intelligence, intuition, cunning, and agility to make larger, longer-lasting, more lucrative trades at legitimate brokerages.

ENDNOTES

1 Richard Wheatley, “The New York Stock Exchange,”

Harper’s Magazine (November 1885).

2 Merrill A. Teague, “Bucket-Shop Sharks: Part II,”

Everybody’s Magazine (July 1906): 38.

3 C. C. Christie, “Bucket-Shop vs. Board of Trade,”

Everybody’s Magazine (November 1906): 707-713.

5 Charles H. Taylor,

History of the Board of Trade of the City of Chicago (1917), 565, 585.

7 Teague, “Bucket-Shop Sharks: Part II,” 43.

8 William H. Stennett,

A History of the Origin of the Place Names (1908), 202.

9 “The Omaha Railroad; A Reorganization Under a Board of New Directors,”

New York Times, December 17, 1882, 14.

10 “Union Pacific,”

New York Times, April 26, 1995, D4.

11 “Arrest Cella for Perjury,”

New York Times, July 15, 1910, 16.

12 “Federal Raids on Bucket Shops,” April 3, 1910.

13 Teague, “Bucket-Shop Sharks: Part II,” 43.

14 “Topics of the Times,”

New York Times, November 17, 1924, 18.

15 John Thom Holdsworth,

Money and Banking (1917), 274-275.

16 Edwin Griswold Nourse,

Brokerage (1918), 225-227.

17 David Hochfelder, “ ‘Where the Common People Could Speculate:’ The Ticker, Bucket Shops, and the Origins of Popular Participation in Financial Markets, 1880-1920,”

Journal of American History (September 2006).

18 “Trading in Odd Lots New Market Force,”

New York Times, April 30, 1916, 21.

19 Robert F. Bruner and Sean D. Carr,

The Panic of 1907 (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), 118.

20 James Anderson Barnes, “Myths of the Bryan Campaign,”

Mississippi Valley Historical Review 34 (1947): 367-404.

In a bucket shop where your margin is a shoestring you don’t play for long pulls. You are wiped too easily and quickly. The desire for constant action irrespective of underlying conditions is responsible for many losses in Wall Street even among the professionals, who feel that they must take home some money every day, as though they were working for regular wages. I was only a kid, remember. I did not know then what I learned later, what made me fifteen years later, wait two long weeks and see a stock on which I was very bullish go up thirty points before I felt that it was safe to buy it. I was broke and was trying to get back, and I couldn’t afford to play recklessly. I had to be right, and so I waited. That was in 1915. It’s a long story. I’ll tell it later in its proper place. Now let’s go on from where after years of practice at beating them I let the bucket shops take away most of my winnings.

In a bucket shop where your margin is a shoestring you don’t play for long pulls. You are wiped too easily and quickly. The desire for constant action irrespective of underlying conditions is responsible for many losses in Wall Street even among the professionals, who feel that they must take home some money every day, as though they were working for regular wages. I was only a kid, remember. I did not know then what I learned later, what made me fifteen years later, wait two long weeks and see a stock on which I was very bullish go up thirty points before I felt that it was safe to buy it. I was broke and was trying to get back, and I couldn’t afford to play recklessly. I had to be right, and so I waited. That was in 1915. It’s a long story. I’ll tell it later in its proper place. Now let’s go on from where after years of practice at beating them I let the bucket shops take away most of my winnings. Anyhow, I came to New York with twenty-five hundred dollars. There were no bucket shops here that a fellow could trust. The Stock Exchange and the police between them had succeeded in closing them up pretty tight.

Anyhow, I came to New York with twenty-five hundred dollars. There were no bucket shops here that a fellow could trust. The Stock Exchange and the police between them had succeeded in closing them up pretty tight. Besides, I wanted to find a place where the only limit to my trading would be the size of my stake. I didn’t have much of one, but I didn’t expect it to stay little forever. The main thing at the start was to find a place where I wouldn’t have to worry about getting a square deal. So I went to a New York Stock Exchange house that had a branch at home where I knew some of the clerks. They have long since gone out of business. I wasn’t there long, didn’t like one of the partners, and then I went to A. R. Fullerton & Co. Somebody must have told them about my early experiences, because it was not long before they all got to calling me the Boy Trader. I’ve always looked young. It was a handicap in some ways but it compelled me to fight for my own because so many tried to take advantage of my youth. The chaps at the bucket shops seeing what a kid I was, always thought I was a fool for luck and that that was the only reason why I beat them so often.

Besides, I wanted to find a place where the only limit to my trading would be the size of my stake. I didn’t have much of one, but I didn’t expect it to stay little forever. The main thing at the start was to find a place where I wouldn’t have to worry about getting a square deal. So I went to a New York Stock Exchange house that had a branch at home where I knew some of the clerks. They have long since gone out of business. I wasn’t there long, didn’t like one of the partners, and then I went to A. R. Fullerton & Co. Somebody must have told them about my early experiences, because it was not long before they all got to calling me the Boy Trader. I’ve always looked young. It was a handicap in some ways but it compelled me to fight for my own because so many tried to take advantage of my youth. The chaps at the bucket shops seeing what a kid I was, always thought I was a fool for luck and that that was the only reason why I beat them so often.

I had heard of two concerns there that did an enormous business all through the Middle West. Their profits must have been huge. They had branch offices in dozens of towns. In fact I had been told that there were no concerns in the East to compare with them for volume of business. They ran openly and the best people traded there without any qualms. A fellow even told me that the owner of one of the concerns was a vice-president of the Chamber of Commerce but that couldn’t have been in St. Louis. At any rate, that is where I went with my five hundred dollars to bring back a stake to use as margin in the office of A. R. Fullerton & Co., members of the New York Stock Exchange.

I had heard of two concerns there that did an enormous business all through the Middle West. Their profits must have been huge. They had branch offices in dozens of towns. In fact I had been told that there were no concerns in the East to compare with them for volume of business. They ran openly and the best people traded there without any qualms. A fellow even told me that the owner of one of the concerns was a vice-president of the Chamber of Commerce but that couldn’t have been in St. Louis. At any rate, that is where I went with my five hundred dollars to bring back a stake to use as margin in the office of A. R. Fullerton & Co., members of the New York Stock Exchange. I knew I could beat them. I was going to play dead safe—carefully and conservatively. My one fear was that somebody might recognise me and give me away, because the bucket shops all over the country had heard of the Boy Trader. They are like gambling houses and get all the gossip of the profesh.

I knew I could beat them. I was going to play dead safe—carefully and conservatively. My one fear was that somebody might recognise me and give me away, because the bucket shops all over the country had heard of the Boy Trader. They are like gambling houses and get all the gossip of the profesh.

‘Ringer my eye, boss! His name is Horace Kent, and he’s a rah-rah boy playing at being used to long pants. He’s all right!’ Well, I let him have his way. That blankety-blank cost me twenty-eight hundred dollars. I don’t grudge it yeh, my boy. But the safe is locked for yeh.”

‘Ringer my eye, boss! His name is Horace Kent, and he’s a rah-rah boy playing at being used to long pants. He’s all right!’ Well, I let him have his way. That blankety-blank cost me twenty-eight hundred dollars. I don’t grudge it yeh, my boy. But the safe is locked for yeh.” I decided to go to his bucket shop. I wondered whether it would be wise to start moderately and work up to a thousand shares or to begin with a plunge, on the theory that I might not be able to trade more than one day. They get wise mighty quick when they’re losing and I did want to buy one thousand B. R. T.

I decided to go to his bucket shop. I wondered whether it would be wise to start moderately and work up to a thousand shares or to begin with a plunge, on the theory that I might not be able to trade more than one day. They get wise mighty quick when they’re losing and I did want to buy one thousand B. R. T. I was sure I could take four or five points out of it. But if they got suspicious or if too many customers were long of that stock they might not let me trade at all. I thought perhaps I’d better scatter my trades at first and begin small.

I was sure I could take four or five points out of it. But if they got suspicious or if too many customers were long of that stock they might not let me trade at all. I thought perhaps I’d better scatter my trades at first and begin small. He isn’t satisfied until he gets it. Well, I certainly wanted to find the solution to my puzzle. I thought I was done with trading in bucket shops. But I was mistaken.

He isn’t satisfied until he gets it. Well, I certainly wanted to find the solution to my puzzle. I thought I was done with trading in bucket shops. But I was mistaken.

That would give the conventional excuse to the big room traders to jump on the market and try to shake out some of the weak commission-house accounts. There would be the usual reactions in the last half hour of the trading, particularly in stocks in which the public had been the most active. Those, of course, also would be the very stocks that Teller’s customers would be most heavily long of, and the shop might be glad to see some short selling in them. There is nothing so nice as catching the suckers both ways; and nothing so easy—with one-point margins.

That would give the conventional excuse to the big room traders to jump on the market and try to shake out some of the weak commission-house accounts. There would be the usual reactions in the last half hour of the trading, particularly in stocks in which the public had been the most active. Those, of course, also would be the very stocks that Teller’s customers would be most heavily long of, and the shop might be glad to see some short selling in them. There is nothing so nice as catching the suckers both ways; and nothing so easy—with one-point margins.

I saw a fellow talking to the manager that I had seen in the St. Louis office the day Teller told me to go back to Dolan. I knew at once that the manager had telegraphed to the home office and they’d sent up one of their men to investigate the story. Crooks don’t trust anybody.

I saw a fellow talking to the manager that I had seen in the St. Louis office the day Teller told me to go back to Dolan. I knew at once that the manager had telegraphed to the home office and they’d sent up one of their men to investigate the story. Crooks don’t trust anybody.

No matter if they moved ten points in ten minutes you could only make two on one ticket. They figured that otherwise the customer was getting too big odds; he stood to lose one dollar and to make ten. And then there were times when all the shops, including the biggest, refused to take orders on certain stocks. In 1900, on the day before Election Day, when it was a foregone conclusion that McKinley would win, not a shop in the land let its customers buy stocks. The election odds were 3 to 1 on McKinley. By buying stocks on Monday you stood to make from three to six points or more. A man could bet on Bryan and buy stocks and make sure money.

No matter if they moved ten points in ten minutes you could only make two on one ticket. They figured that otherwise the customer was getting too big odds; he stood to lose one dollar and to make ten. And then there were times when all the shops, including the biggest, refused to take orders on certain stocks. In 1900, on the day before Election Day, when it was a foregone conclusion that McKinley would win, not a shop in the land let its customers buy stocks. The election odds were 3 to 1 on McKinley. By buying stocks on Monday you stood to make from three to six points or more. A man could bet on Bryan and buy stocks and make sure money. The bucket shops refused orders that day.

The bucket shops refused orders that day. Better known as TCI, the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Co. was a major U.S. steel manufacturer with assets in coal and iron ore mining as well as railways. The company was one of 12 that comprised the first Dow Jones Industrial Average index in 1896. It was a direct competitor to J. P. Morgan’s massive United States Steel Corporation until he was able to secure control during the turmoil surrounding the Panic of 1907. At the time, TCI owned an estimated 800 million tons of iron ore and 2 billion tons of coal.19

Better known as TCI, the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Co. was a major U.S. steel manufacturer with assets in coal and iron ore mining as well as railways. The company was one of 12 that comprised the first Dow Jones Industrial Average index in 1896. It was a direct competitor to J. P. Morgan’s massive United States Steel Corporation until he was able to secure control during the turmoil surrounding the Panic of 1907. At the time, TCI owned an estimated 800 million tons of iron ore and 2 billion tons of coal.19 William Jennings Bryan ran again unsuccessfully as a Democrat in the 1900 presidential election. Much of the same dynamic that played out in the 1896 contest between Bryan and William McKinley recurred. The economy was vibrant heading into the election. And America had won the brief Spanish-American War of 1898.

William Jennings Bryan ran again unsuccessfully as a Democrat in the 1900 presidential election. Much of the same dynamic that played out in the 1896 contest between Bryan and William McKinley recurred. The economy was vibrant heading into the election. And America had won the brief Spanish-American War of 1898.