III

It takes a man a long time to learn all the lessons of all his mistakes. They say there are two sides to everything. But there is only one side to the stock market; and it is not the bull side or the bear side, but the right side. It took me longer to get that general principle fixed firmly in my mind than it did most of the more technical phases of the game of stock speculation.

I have heard of people who amuse themselves conducting imaginary operations in the stock market to prove with imaginary dollars how right they are. Sometimes these ghost gamblers make millions. It is very easy to be a plunger that way. It is like the old story of the man who was going to fight a duel the next day.

His second asked him, “Are you a good shot?”

“Well,” said the duelist, “I can snap the stem of a wineglass at twenty paces,” and he looked modest.

“That’s all very well,” said the unimpressed second. “But can you snap the stem of the wineglass while the wineglass is pointing a loaded pistol straight at your heart?”

With me I must back my opinions with my money. My losses have taught me that I must not begin to advance until I am sure I shall not have to retreat. But if I cannot advance I do not move at all. I do not mean by this that a man should not limit his losses when he is wrong. He should. But that should not breed indecision. All my life I have made mistakes, but in losing money I have gained experience and accumulated a lot of valuable don’ts. I have been flat broke several times, but my loss has never been a total loss. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be here now. I always knew I would have another chance and that I would not make the same mistake a second time. I believed in myself.

A man must believe in himself and his judgment if he expects to make a living at this game. That is why I don’t believe in tips. If I buy stocks on Smith’s tip I must sell those same stocks on Smith’s tip. I am depending on him. Suppose Smith is away on a holiday when the selling time comes around? No, sir, nobody can make big money on what someone else tells him to do. I know from experience that nobody can give me a tip or a series of tips that will make more money for me than my own judgment. It took me five years to learn to play the game intelligently enough to make big money when I was right.

I didn’t have as many interesting experiences as you might imagine. I mean, the process of learning how to speculate does not seem very dramatic at this distance. I went broke several times, and that is never pleasant, but the way I lost money is the way everybody loses money who loses money in Wall Street. Speculation is a hard and trying business, and a speculator must be on the job all the time or he’ll soon have no job to be on.

My task, as I should have known after my early reverses at Fullerton’s, was very simple: To look at speculation from another angle. But I didn’t know that there was much more to the game than I could possibly learn in the bucket shops. There I thought I was beating the game when in reality I was only beating the shop. At the same time the tape-reading ability that trading in bucket shops developed in me and the training of my memory have been extremely valuable. Both of these things came easy to me. I owe my early success as a trader to them and not to brains or knowledge, because my mind was untrained and my ignorance was colossal. The game taught me the game. And it didn’t spare the rod while teaching.

I remember my very first day in New York. I told you how the bucket shops, by refusing to take my business, drove me to seek a reputable commission house. One of the boys in the office where I got my first job was working for Harding Brothers, members of the New York Stock Exchange. I arrived in this city in the morning, and before one o’clock that same day I had opened an account with the firm and was ready to trade.

I didn’t explain to you how natural it was for me to trade there exactly as I had done in the bucket shops, where all I did was to bet on fluctuations and catch small but sure changes in prices. Nobody offered to point out the essential differences or set me right. If somebody had told me my method would not work I nevertheless would have tried it out to make sure for myself, for when I am wrong only one thing convinces me of it, and that is, to lose money. And I am only right when I make money. That is speculating.

They were having some pretty lively times those days and the market was very active. That always cheers up a fellow. I felt at home right away. There was the old familiar quotation board in front of me, talking a language that I had learned before I was fifteen years old. There was a boy doing exactly the same thing I used to do in the first office I ever worked in. There were the customers—same old bunch—looking at the board or standing by the ticker calling out the prices and talking about the market. The machinery was to all appearances the same machinery that I was used to. The atmosphere was the atmosphere I had breathed since I had made my first stock-market money—$3.12 in Burlington. The same kind of ticker and the same kind of traders, therefore the same kind of game. And remember, I was only twenty-two. I suppose I thought I knew the game from A to Z. Why shouldn’t I?

I watched the board and saw something that looked good to me. It was behaving right. I bought a hundred at 84. I got out at 85 in less than a half hour. Then I saw something else I liked, and I did the same thing; took three-quarters of a point net within a very short time. I began well, didn’t I?

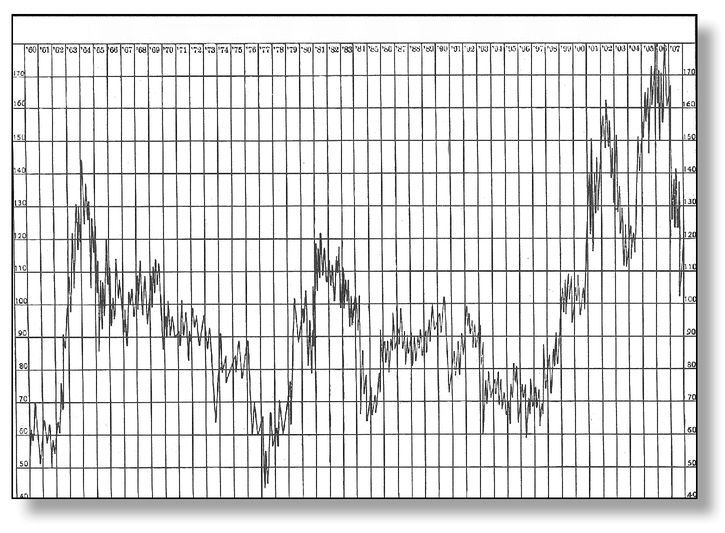

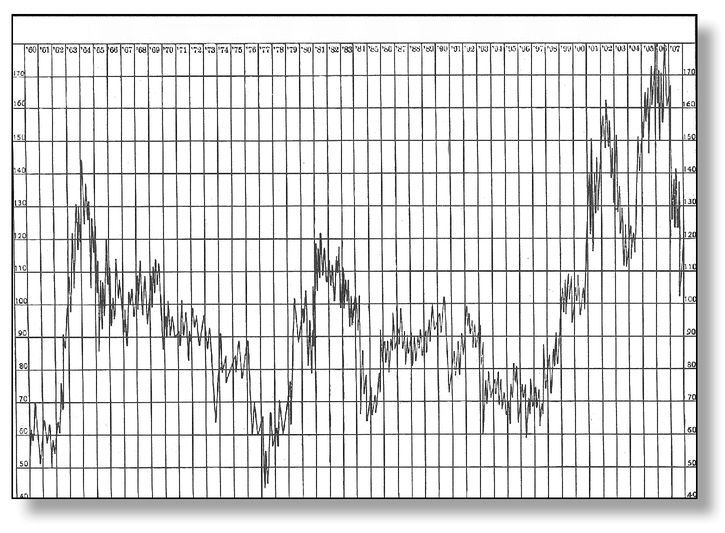

AVERAGE PRICE ACTION OF TEN LEADING STOCKS (1860 to 1907)

Now mark this: On that, my first day as a customer of a reputable Stock Exchange house, and only two hours of it at that, I traded in eleven hundred shares of stock, jumping in and out. And the net result of the day’s operations was that I lost exactly eleven hundred dollars. That is to say, on my first attempt, nearly one-half of my stake went up the flue. And remember, some of the trades showed me a profit. But I quit eleven hundred dollars minus for the day.

It didn’t worry me, because I couldn’t see where there was anything wrong with me. My moves, also, were right enough, and if I had been trading in the old Cosmopolitan shop I’d have broken better than even. That the machine wasn’t as it ought to be, my eleven hundred vanished dollars plainly told me. But as long as the machinist was all right there was no need to stew. Ignorance at twenty-two isn’t a structural defect.

After a few days I said to myself, “I can’t trade this way here. The ticker doesn’t help as it should!” But I let it go at that without getting down to bed rock. I kept it up, having good days and bad days, until I was cleaned out. I went to old Fullerton and got him to stake me to five hundred dollars. And I came back from St. Louis, as I told you, with money I took out of the bucket shops there—a game I could always beat.

I played more carefully and did better for a while. As soon as I was in easy circumstances I began to live pretty well. I made friends and had a good time. I was not quite twenty-three, remember; all alone in New York with easy money in my pockets and the belief in my heart that I was beginning to understand the new machine.

I was making allowances for the actual execution of my orders on the floor of the Exchange, and mov ing more cautiously. But I was still sticking to the tape—that is, I was still ignoring general principles; and as long as I did that I could not spot the exact trouble with my game.

3.1 Although Livermore describes himself as a boy, he was about 24 years old. It had been 10 years since he arrived in Boston and first began studying the rhythm of prices. With some well-honed skills at his disposal, he was well positioned for the big bull market that lay ahead.

The 1901 market boom was fueled by the widespread economic prosperity the United States enjoyed at the beginning of the twentieth century. Factors included a succession of plentiful harvests, increased global gold production, an expanding trade surplus, and victory in the war against Spain. The situation was remarkable considering the nation’s crippled financial state a short time earlier in 1894, when key industries were declining, big companies drifting toward bankruptcy, and the government was forced to borrow at high interest rates from Europe to maintain the public credit.

1The chart on page 37 shows the price action of the 10 leading stocks from 1860 to 1907. European crop failures increased demand for American wheat, boosting U.S. gold reserves from $44.5 million in 1896 to $254 million in 1898. This gold cache enabled legislation to be passed in March 1900 that officially put the United States back on the gold standard, ending the experiments with nonconvertible bills called greenbacks during the Civil War, and bimetallism—convertibility into both gold and silver—in the years that followed.

Companies and investors alike benefited from sounder monetary policy. But during the summer, as Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan crisscrossed the country during the 1900 presidential campaign, business activity slowed as the country was gripped in an 1896-style “free-silver” scare. On August 22, only 86,000 shares traded on the New York Stock Exchange. On September 24, the Dow Jones Industrial Average set the year’s closing low at 52.96. Following President McKinley’s reelection in November, stocks surged as gold poured into the United States from Europe once foreign investors were reassured of U.S. monetary stability. The Dow Jones Industrials leapt 34% from the summer low to close at 71.04 on December 27. The boom continued into 1901, and on January 7, the NYSE had its fi rst 2-million-share day.

Veteran banker Henry Clews, who had helped finance the Civil War by cleverly marketing U.S. federal bonds to Europeans, captures the mood in his memoir:

Wall Street changed with almost magical suddenness from depression and apprehension to confidence and buoyancy with the defeat of Bryan and his silver heresy. … Large capitalists all over the country began to buy stocks and bonds on so heavy a scale that prices shot up rapidly… and very soon orders poured into the Stock Exchange

from people of smaller means everywhere, and a tremendous bull market for stocks resulted, with too many men staking, or ready to stake, their bottomdollar on the rise.23.2 As the United States attracted gold from around the world, New York Times financial editor Alexander Dana Noyes said the “reservoir of American capital seemed inexhaustible; it filled up on one side faster than it could be drained into these various enterprises on the other. It was then that the scheme of recapitalizing American industry was conceived.”

3This was an era in which companies consolidated their power by obtaining controlling interests in rivals. Clews said observers “witnessed an unexampled rush to form combinations of industrial and railroad interests, or trusts, and generally to capitalize the concerns taken in for many times the amount of their previous capital or real value.” Between 1895 and 1904, there were 319 mergers with a total capitalization of more than $6 billion, a massive number at the time.

4This behavior is similar to the 1980s and mid-2000s booms in leveraged buyouts and private equity acquisitions. In both eras, vast amounts of money were borrowed from gullible lenders to magnify returns. In the first decade of the twentieth century, consolidators would float new shares of equity, bid up the price through active price manipulation, and sell them to the new class of small investors being drawn from bucket shops into legitimate brokerage houses. As shares of new industrial combination were absorbed, public naïveté encouraged bankers to create new ones.

Wall Street enjoyed the greatest boom it had yet seen. Lefevre notes that “old timers perforce stopped bragging about the boom of ‘79 and ‘80.”

5 He was referring to the booms of 1879 and 1880 brought about by passage of the Resumption Act, which allowed conversion of dollars into gold.

Although the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 had outlawed monopolies, this era did not end until passage of the Clayton Antitrust Act in 1914. The law allowed regulators to prevent acquisitions if they were intended to lessen competition or lay the groundwork to create a monopoly.

We ran into the big boom of 1901 and I made a great deal of money—that is, for a boy.

You remember those times? The prosperity of the country was unprecedented. We not only ran into an era of industrial consolidations and combinations of capital that beat anything we had had up to that time, but the public went stock mad.

In previous flush times, I have heard, Wall Street used to brag of two-hundred-and-fifty-thousand-share days, when securities of a par value of twenty-five million dollars changed hands. But in 1901 we had a three-million-share day. Everybody was making money. The steel crowd came to town, a horde of millionaires with no more regard for money than drunken sailors. The only game that satisfied them was the stock market. We had some of the biggest high rollers the Street ever saw: John W. Gates, of ‘Bet-you-a-million’ fame, and his friends, like John A. Drake, Loyal Smith, and the rest; the Reid-Leeds-Moore crowd, who sold part of their Steel holdings and with the proceeds bought in the open market the actual majority of the stock of the great Rock Island system; and Schwab and Frick and Phipps and the Pittsburgh coterie; to say nothing of scores of men who were lost in the shuffle but would have been called great plungers at any other time.

A fellow could buy and sell all the stock there was. Keene made a market for the U. S. Steel shares.

A broker sold one hundred thousand shares in a few minutes. A wonderful time! And there were some wonderful winnings. And no taxes to pay on stock sales! And no day of reckoning in sight.

Of course, after a while, I heard a lot of calamity howling and the old stagers said everybody—except themselves—had gone crazy. But everybody except themselves was making money. I knew, of course, there must be a limit to the advances and an end to the crazy buying of A. O. T.—Any Old Thing—and I got bearish. But every time I sold I lost money, and if it hadn’t been that I ran darn quick I’d have lost a heap more. I looked for a break, but I was playing safe—making money when I bought and chipping it out when I sold short—so that I wasn’t profiting by the boom as much as you’d think when you consider how heavily I used to trade, even as a boy.

3.3 Livermore lists some of the biggest players of the day to show who he was up against in the market.

John A. Drake, the son of a former Iowa governor, was a banker and a member of the Chicago Board of Trade. He was also a well-known betting partner and business associate of John Gates. Drake was a pallbearer at Gates’ funeral service, which was held at the Plaza Hotel in New York City in 1911. Drake afterward remained close to Gates’ son, Charles, and at racetracks the two became known as the largest speculators of the time on the American turf.

6,

7 He was equally keen on trading commodities. It was reported that once while his father was long wheat, Drake “resisted all invitations to come in at $60 and $70, but came in strong at $80, on the short side, to his own great advantage and papa’s surprise.”

8

Loyal Smith was a successful real estate investor who made millions by buying properties in the toniest sections of Manhattan. The New York Times reported that Smith got his start as a “daring, determined, energetic, and shrewd young Yankee.” Early in his career, he relocated to Chicago and fell in with Gates and Drake. He helped the group organize the American Steel & Wire Co., which landed Smith his first fortune of $1.6 million. Among the Chicago crowd, according to Lefevre, Smith was “one of the heaviest players of the bunch, bigger than John W. Gates himself.” At the time of his death in 1908, at age 54, Smith was originally estimated to be worth$5 million. But losses incurred while speculating on stocks and coffee had in fact reduced his estate to around $1 million.

9

The Reid-Leeds-Moore crowd were four men that dominated the tin-plating industry in this era, a business that was important both for its use in rust-proofing steel and for making cans and containers. They each had nicknames: “Tin Plate” William B. Leeds; “promoter extraordinary” Judge William H. Moore and his brother James H. Moore; and “Czar” Daniel Gray Reid. The group made a fortune when they sold their American Tin Plate holdings to U.S. Steel.

10,

11,

12

The Rock Island system was formally known as the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railway Company. It reached from Chicago to Denver, and was sold for $20 million in 1901. It is impossible to say what the actual profits were for the group. The Kernel of Finance and Politics, a monthly journal, wrote in 1914 that details of Rock Island’s reorganization were still lacking and that bankers “of the highest talent are applying themselves to the work with full faith in eventual success.”

13 When Reid was questioned on the matter, he claimed that he had “burned his books at the end of the month.”

14

3.4 James R. Keene was one of th e “b ol dest and ab lest operators that ever lived,” according to Lefevre, who wrote about the trader many times in magazines. Keene specialized in manipulating stocks to attract investment interest from the masses. Lefevre compares the practice to labeling and advertising stocks to “coax and cajole outsiders to come into the market.” In reality, it was a matter of supporting the market at critical moments to give the illusion of deep, sustained buying power. Once convinced, Lefevre said, the outside investors and speculators create a “dizzying upward whirl of security values” that would allow insiders to sell their substantial stakes profitably.

Keene’s skills were instrumental in creating excitement in the initial sale of U.S. Steel shares, which will be explained in detail later.

153.5Northern Pacific was a railroad controlled by James J. Hill. Backed by J.P. Morgan, the tycoon also controlled the Great Northern railroad. Together the lines dominated transportation through Wisconsin, Minnesota, the Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming, Oregon and Washington. Hill also controlled the Illinois Central line, which paralleled the Mississippi River out of Louisiana before connecting to the major eastern railroads in Chicago. Hill’s intention in cobbling together his system was to transport American cotton from the South to Japan by way of Seattle. “Little Nipper” was traders’ nickname for Northern Pacific common stock due to its NP symbol. Its preferred shares were called “Big Nipper.”

There was one stock that I wasn’t short of, and that was Northern Pacific. My tape reading came in handy. I thought most stocks had been a bought to a standstill, but Little Nipper behaved as if it were going still higher.

We know now that both the common and the preferred were being steadily absorbed by the Kuhn-Loeb-Har riman combination.

Well, I was long a thousand shares of Northern Pacific common, and held it against the advice of everybody in the office. When it got to about 110 I had thirty points profit, and I grabbed it. It made my balance at my brokers’ nearly fifty thousand dollars, the greatest amount of money I had been able to accumulate up to that time. It wasn’t so bad for a chap who had lost every cent trading in that selfsame office a few months before.

3.6 The accumulation of Northern Pacific shares by Edward Henry Harriman and his bankers Kuhn, Loeb was a single strand in the most epic business battle of the new century. The fight resulted first in an explosive move higher for the market in which Livermore benefited, and then a panic that cost him a fortune. It will take a while to explain.

Harriman was a speculator, a railroad consolidator, and one of the dominant figures of the early twentieth century. Although his family was pedigreed, Harriman was born into poverty in 1848. His father, Orlando Harriman, struggled as the pastor of a church in Staten Island until an inheritance secured his family’s finances.

Harriman’s early education mirrors Livermore’s: As a teen, he worked as a clerk in a Wall Street office. Success came quickly as he learned to speculate during the volatile years during and after the Civil War—a period marred not just by the battle between the states but also by President Lincoln’s assassination, currency fluctuations, disputes over ownership of railroads, and attempts to corner the gold market.

By 1870, at age 22, Harriman had made enough to buy a seat on the New York Stock Exchange at a time when there were only 70 actively traded issues.

16 Through the aid of the richer branches of the Harriman family he soon formed the brokerage firm Harriman & Co. Lefevre, in a 1901 American Magazine article, wrote at length about Harriman’s formative stage:

He learned the routine of a broker’s life; the ups and downs of stocks, panics and gain

ing a knowledge of technical market conditions surpassed by few other operators big or little. The game of the Street he knew, and knows it still, from the sub-cellar to the gilt ball at the end of the flag

pole, for he began at the bottom and has since climbed as high as any human being can climb in Wall Street.

17Harriman earned a reputation, which he would keep throughout his life, of being cold and detached. He had a great appetite for knowledge, dismissing the theory that the ticker’s verdicts were determined by chance. The more he knew, the less he felt he needed to talk.

In 1883, through the influence of a friend and associate, Harriman was elected a director of the Illinois Central railroad. By 1887, he was vice president of the line. Focusing on exacting profit from all available angles, Harriman labored intensely—“literally burned the midnight oil mastering details,” according to Lefevre.

18 He was cognizant of even the price of rail spikes so that contractors could not gain an advantage when submitting bids.

From 1890 to 1896, Harriman accumulated wealth through speculations and acquisitions, building his reputation for deal-making acumen among the rich men he would later need as allies. The economic downturn that followed the Panic of 1893 bankrupted many railroads, leaving a rich field of opportunity for ambitious men. Lefevre calls the deals that followed the “rungfinders and ladder-builders for Harriman” as he worked through his apprenticeship in the railways.

Harriman eventually took control of the Union Pacifi c, which he helped take out of bankruptcy in 1898. The railroad expanded rapidly through a string of acquisitions. First there was a pair of lines in Oregon, then the purchase of the large Southern Pacific system in February 1901. Soon Harriman’s road dominated the territory west from Omaha, across the original Transcontinental Railroad through Wyoming and Utah before splitting south to San Francisco in California and north to Oregon and Washington.

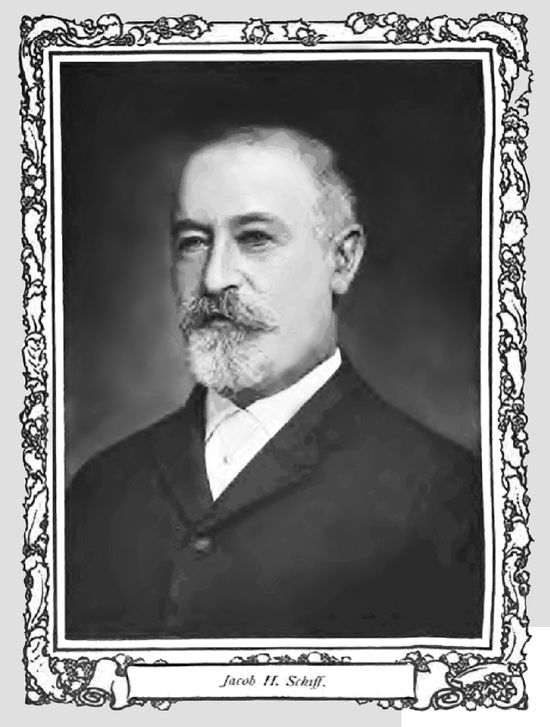

Kuhn, Loeb & Co., led by Jacob Schiff (see photo on next page), became Harriman’s banker. Together they formed a syndicate with capital backing from the Rockefellers of Standard Oil, the Vanderbilts, and the Goulds.

19A battle between Harriman and rival tycoon J.P. Morgan, who controlled Northern Pacific, and their proxies brewed for years as their competing rail networks wrestled for supremacy in the states west of the Mississippi River.

The first key rail fight that led to the Panic of 1901 was over the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, which provided an entrance into Chicago and access to a feeder network of railways throughout the fertile Mississippi plain. If one wanted to control the shipment of American crops across the Pacific and the transshipment of Asian goods into America’s heartland, the Burlington was a critical asset. Its president, Charles Perkins, had made the line the most efficient of the Midwestern railroads and was nearing retirement. Everyone knew the Burlington had to be sold.

Harriman moved first. In August 1899, at a luncheon he organized in Chicago, Harriman pulled aside a representative of the Burlington and wasted no words: He believed the Union Pacific and the Burlington should combine and wondered if Perkins would be interested. Perkins told Harriman that the Burlington was not for sale, but if it were, the price would be $200 a share.

This was too rich for Harriman’s taste, but he appreciated the challenge. In response, in mid-March, he made a dual counteroffer: $150 a share in cash or $200 a share in Union Pacific bonds. Perkins was unimpressed and firmly maintained that the price was $200 a share in cash.

Soon Harriman was distracted with the purchase of the Southern Pacific, which was labeled a “railway revolution” by the press (see table on the next page for a glimpse of the rising railroad stocks).

20 He did, however, form a pool to buy Burlington stock in the open market. If Perkins wanted to play tough, Harriman might as well strengthen his hand.

21Next, it was Morgan’s turn. His ally, James Hill, was dispatched in February 1901 to propose a merger between the Great Northern and the Burlington through a stock swap. Perkins again maintained that the price was $200 a share in cash. At the same time, Hill’s associates had been accumulating Burlington stock. In a meeting on February 24, Perkins and his top advisors decided that Morgan’s Northern Pacifi c “would be a stronger and safer place for us to land.”

22Unaware of Perkins’s preference, and with rising suspicion as Burlington’s stock soared, Harriman and Schiff paid a visit to Hill in late March to ask if he was trying to gain control of the Burlington. Schiff and Hill were old friends, both serving as directors on the board of Great Northern, so when Hill coldly replied that he was not buying and had no interest, Schiff believed him. Harriman made no mention of his intentions.

Having bought himself some time, Hill quickly set off for Boston to meet with Perkins to set terms for the sale of the Burlington to Northern Pacific. After reporters spotted the two meeting on March 30 and the news went public, Harriman fumed. Schiff quickly arranged an audience with Hill on neutral ground. The air charged with tension, Hill apologized to Schiff but said it was necessary because of the banker’s association with Harriman and Union Pacific. Harriman thought Hill had “paid a damned fool price for the Burlington,” according to accounts of the meeting relayed to Lefevre, but nonetheless urged him to consider the interests of the Union Pacific and not close the deal until an agreement could be reached.

jack II Schall

When Hill refused to do so, Harriman spewed forth with fury: “Then you will have to take the conse quences.”

23Schiff, who had started his career in the service of Morgan, went to the great banker’s office in an attempt to avoid all-out war. He was quickly rebuffed as Morgan was preparing for his annual trip to Europe to restore his health after expending great energy in the U.S. Steel merger. Turning to Morgan’s partner, Robert Bacon, Schiff proposed that the Union Pacific take a one-third interest in the Burlington. “It’s too late,” Bacon replied. “Nothing can be done.” The Burlington was divided between the Great Northern and the Northern Pacific, with its shareholders tendering shares in exchange for $200 a share in bonds from the two Morgan-Hill roads. Hill and Morgan, who had been buying the Burlington from $100 up to $175 in large blocks, profited greatly.

24Harriman, with his “Napoleonic plans” for the railways, according to Lefevre, prepared to counter this direct challenge on his burgeoning empire.

25THE ECONOMIST. [May 4, 1901.

If you remember, the Harriman crowd notified Morgan and Hill of their intention to be represented in the Burlington-Great Northern-Northern Pacific combination, and then the Morgan people at first instructed Keene to buy fifty thousand shares of N. P. to keep the control in their possession. I have heard that Keene told Robert Bacon to make the order one hundred and fifty thousand shares and the bankers did. At all events, Keene sent one of his brokers, Eddie Norton, into the N. P. crowd and he bought one hundred thousand shares of the stock. This was followed by another order, I think, of fifty thousand shares additional, and the famous corner followed. After the market closed on May 8, 1901, the whole world knew that a battle of financial giants was on. No two such combinations of capital had ever opposed each other in this country. Harriman against Morgan; an irresistible force meeting an immovable object.

There I was on the morning of May ninth with nearly fifty thousand dollars in cash and no stocks. As I told you, I had been very bearish for some days, and here was my chance at last. I knew what would happen—an awful break and then some wonderful bargains. There would be a quick recovery and big profits—for those who had picked up the bargains. It didn’t take a Sherlock Holmes to figure this out. We were going to have an opportunity to catch them coming and going, not only for big money but for sure money.

3.7 The grand battle consumed the market in May 1901. It is important to understand the mood of the time. Ordinary investors had recently been worked into a frenzy as U.S. Steel shares were promoted and railroad stocks were rising fast on various rumors of insider accumulations and mergers. Lefevre recounts a “raging public speculation in stocks” while Clews talks of a “restless sea of reckless stock speculation that swept the American people into its vortex, with all its razzle-dazzle extravagance.”

In this hyped-up environment, Harriman’s attempt to retaliate against Morgan for grabbing the Burlington acted like a spark igniting a pool of gasoline. The resulting jump in prices, then panic, caused “intense excitement, demoralization, and confusion” that “convulsed the stock market in a way that alarmed money lenders, destroyed confidence, and caused a general rush to sell stocks which brought them down with a crash, involving many thousands in ruinous losses,” according to Clews’s account.

26

With Burlington locked into the Great Northern and the Northern Pacific network, Harriman attacked Morgan with a daring raid: He bought Northern Pacific shares on the open market. The Northern Pacific was loosely controlled, with $80 million in common and $75 million in preferred shares outstanding. Of this, James Hill and Morgan controlled only $35 million on the belief that no one was crazy enough to take down a $155 million railroad in the open market. But Harriman had the nerve, and the reserves, to “buy the mare to get the filly.”

27The plan was bold. If he were to succeed, Harriman’s Union Pacific would control two-thirds of the nation’s railways and would relegate the Morgan-Hill system to a thin strip of land just under the Canadian border.

The market boiled as Harriman and his allies accumulated $42 million of Northern Pacific preferred (a majority) and $37 million of the common shares (which was 40,000 shares or so short of being a majority) by the end of April 1901. Large price rises in other railroads threw the market off the trail and set the rumor mill abuzz.

Meanwhile, Hill watched the ticker in his Seattle office with great unease as shares in his Northern Pacific steadily climbed. Something was amiss. With Morgan steaming for Europe, Hill felt it best to return to New York. He arrived on the afternoon of May 3 after riding a special express on the Great Northern line to St. Paul “with unlimited right of way over everything”—making it the fastest run to the Mississippi yet seen.

28As Hill went to see Jacob Schiff, traders were sending Union Pacific, Northern Pacific, and the rest of the list down on heavy profit taking. The New York Times wrote that since the boom that had started in November 1900, “nothing of this sort had intervened, though conservative advisors have been pointing out for weeks past that dangers were lurking in the market, that over-confidence and over-enthusiasm were inducing over-trading and inviting smashes.”

29A dramatic scene played out in the Kuhn, Loeb & Co. offices after Schiff admitted his firm was buying Northern Pacific on Harriman’s orders. “But you can’t get control!” Hill cried in outrage. “That may be,” Schiff replied, “but we’ve got a lot of it.” After storming out, a shaken Hill immediately ordered Morgan’s office to telegraph him in France for the authority to purchase at least $15 million worth of Northern Pacific stock to fight off Harriman.

Harriman’s position was actually weaker than Schiff made it out to be. Although he maintained a majority of the preferred stock, he was still without a clear majority of the common. This was a problem since Northern Pacific’s board had the authority to retire the preferred stock at any time after January 1, 1902. While he could elect his own board at the annual shareholders’ meeting in October, Harriman feared that Morgan would somehow postpone the meeting until after the New Year.

Despite the assurances of legal counsel that a majority of the total stock was sufficient, Harriman wanted to leave nothing to chance. Bedridden with a cold, he decided that the final 40,000 shares should be purchased during the shortened Saturday trading session on May 4 to eliminate any weakness in the plan and ease his worries. Destiny foiled Harriman when he telephoned Kuhn, Loeb looking for Schiff, who was worshipping at a synagogue. A junior partner received the order, but the order was never filled. After much delay, Schiff was informed of Harriman’s request, but he thought it unnecessary and ignored it.

Across the Atlantic, Morgan was enjoying a respite from trading when he received Hill’s cable. Quickly dictating a reply, Morgan authorized his men to buy at any price all the Northern Pacific common stock needed to maintain control. But his message did not arrive in New York until the night of Sunday, May 5—too late if Harriman’s order had been filled by Kuhn, Loeb.

Everything happened as I had foreseen. I was dead right and—I lost every cent I had! I was wiped out by something that was unusual. If the unusual never happened there would be no difference in people and then there wouldn’t be any fun in life. The game would become merely a matter of addition and subtraction. It would make of us a race of bookkeepers with plodding minds. It’s the guessing that develops a man’s brain power. Just consider what you have to do to guess right.

On Monday, Northern Pacific stock “came strong from London, and opened with a burst of activity”

30 as the Hill-Morgan brokers, led by James Keene, fanned across the exchange floor bidding for all the NP common shares to be had as the price rose from $110 to $133. Newspapers spoke of “wild scenes on the floor” as the day’s action was “in some respects the most remarkable of any that Wall Street has yet seen.” A total of 361,000 shares of Northern Pacific were traded, of which Keene’s broker, Eddie Norton, bought 200,000—a new single-day record and slightly more than Livermore mentions.

31During the tumult, Harriman had phoned Kuhn, Loeb to ask why he received no confirmation on his 40,000-share order two days before. All he heard in reply was a lengthy, maddening silence before he was told of Schiff’s decision to ignore the order. Schiff never explained why he made this decision but did maintain that the fault was his alone. Realizing that “the whole object of our work might be lost,” Harriman pulled himself out of bed and down to Schiff’s office to plan strategy.

32On Tuesday, Morgan’s men ran Northern Pacific shares up to nearly $150 as they continued to buy heavily. Other stocks fell away as short sellers, who were questioning the legitimacy of the rise in the Northern Pacific, dunped other holdings to cover mounting losses. By the close of trading, Morgan and Hill had the shares they needed to maintain control.

The beginning of the end started Wednesday afternoon as stocks broke by 20 points; Northern Pacific zoomed from $143 to $200 and squeezed short sellers. That night, brokers crowded into the Waldorf hotel and filled the air with tobacco smoke and rumor. James Keene made an appearance but disclosed nothing despite the desperate pleas of traders.

33 Broker Bernard Baruch observed the scene: “One look inside the Waldorf that night was enough to bring home the truth of how little we differ from animals after all. From a palace the Waldorf had been transformed into the den of frightened men at bay.”

34On Thursday, it became apparent that a corner was on, as more Northern Pacifi c had been sold short and contracted for delivery than could be bought or borrowed. Panic ensued when the price of Northern Pacifi c rose to $1,000 amid frantic attempts to cover shorts. The two big holders, Harriman and Morgan, were not interested in selling. Other stocks plummeted as the interest rate on short-term call loans went to 60%. For a few hours, based on the day’s lows,“ a good part of Wall Street was technically insolvent.”

35 Again, Baruch observes the chaos:

When one broker walked into the crowd, other traders, thinking he might have some Northern Pacific stock, charged him, banging him against the railing. “Let me go, will you?” he roared. “I haven’t a share of the damned stock. Do you think I carry it in my clothes?”

Then, through the desperate crowd strode Al Stern, of Hertzfield & Stern, a young and vigorous broker. He had come as an emissary of Kuhn, Loeb & Company, which was handling Harriman’s purchases of Northern Pacific. Stern blithely inquired: “Who wants to borrow Northern Pacific? I have a block to lend.”

The market fairly boiled, as I had expected. The transactions were enormous and the fluctuations unprecedented in extent. I put in a lot of selling orders at the market. When I saw the opening prices I had a fit, the breaks were so awful. My brokers were on the job. They were as competent and conscientious as any; but by the time they executed my orders the stocks had broken twenty points more. The tape was way behind the market and reports were slow in coming in by reason of the awful rush of business. When I found out that the stocks I had ordered sold when the tape said the price was, say, 100 and they got mine off at 80, making a total decline of thirty or forty points from the previous night’s close, it seemed to me that I was putting out shorts at a level that made the stocks I sold the very bargains I had planned to buy. The market was not going to drop right through to China. So I decided instantly to cover my shorts and go long.

The first response was a deafening shout. There was an infinitesimal pause and then the desperate brokers rushed at Stern. Struggling to get near enough to him to shout their bids, they kicked over stock tickers. Strong brokers thrust aside the weak ones. Hands were waving and trembling in the air.

Almost doubled over on a chair, his face close to a pad, Stern began to note his transactions. He would mumble to one man, “All right, you get it,” and then complain to another, “For heaven’s sake, don’t stick your finger in my eye.”

One broker leaned over and snatched Stern’s hat, with which he beat a tattoo on Stern’s head to gain attention. “Put back my hat!” shrieked Stern. “Don’t make such a confounded excitement and maybe I can do better by you.”

But the traders continue to push and fight and nearly climbed over one another’s backs to get to Stern. They were like thirst-crazed men battling for water, with the biggest, strongest, and loudest faring best. Soon Stern had loaned the last of his stock. His face white, and his clothes disheveled, he managed to break away.

36Realizing the gravity of the situation, Harriman and Morgan joined forces to prevent catastrophe. Morgan, still in Europe, rushed to the Paris office of Morgan, Harjes & Co. as news of the panic reached him. Reporters swarmed as he frantically issued orders to New York. Cursing the newsmen as “idiots” and “rascals,” and even threatening one with murder, Morgan famously stated when asked if some statement were not due the public: “I owe the public nothing.”

37My brokers bought; not at the level that had made me turn, but at the prices prevailing in the Stock Exchange when their floor man got my orders. They paid an average of fifteen points more than I had figured on. A loss of thirty-five points in one day was more than anybody could stand.

The ticker beat me by lagging so far behind the market. I was accustomed to regarding the tape as the best little friend I had because I bet according to what it told me. But this time the tape double-crossed me. The divergence between the printed and the actual prices undid me. It was the sublimation of my previous unsuccess, the selfsame thing that had beaten me before. It seems so obvious now that tape reading is not enough, irrespective of the brokers’ execution, that I wonder why I didn’t then see both my trouble and the remedy for it.

Stern returned to the floor a few minutes before the 2:15 P.M. deadline for short sellers to deliver stock certificates (see photo, which is believed to depict Stern before a crowd during the May 9 panic). Mounting a chair and shouting to be heard, he announced his firm would not demand delivery of Northern Pacific shares sold short. Stern was followed by Eddie Norton, representing the Morgan forces, who also announced that his firm would not force delivery. Immediately, Northern Pacific sold off and closed at $325. The crisis was over.

38For Livermore, the May 1901 panic reinforced his earlier lessons about the difficulty of adapting his bucket shop trading strategy, which depended on instant fulfillment (since no actual stock transaction needs to occur), to actual purchases and sales on the New York Stock Exchange. Prices fell upward of 20 points between sales as the ticker lagged the action on the floor by 10 minutes. Livermore tried to compensate by placing limit orders but found that his orders simply went unfilled. As a result of this experience, Livermore learned the importance of capturing the big, secular movements in the stock market instead of the short-term undulations he had profited from in the past.

39 The stock table above shows the $840 swing in Little Nipper from a low of $160 to a high of $1000, and then the close at $325.

I did worse than not see it; I kept on trading, in and out, regardless of the execution. You see, I never could trade with a limit. I must take my chances with the market. That is what I am trying to beat—the market, not the particular price. When I think I should sell, I sell. When I think stocks will go up, I buy. My adherence to that general principle of speculation saved me. To have traded at limited prices simply would have been my old bucket-shop method inefficiently adapted for use in a reputable commission broker’s office. I would never have learned to know what stock speculation is, but would have kept on betting on what a limited experience told me was a sure thing.

Whenever I did try to limit the prices in order to minimize the disadvantages of trading at the market when the ticker lagged, I simply found that the market got away from me. This happened so often that I stopped trying. I can’t tell you how it came to take me so many years to learn that instead of placing piking bets on what the next few quotations were going to be, my game was to anticipate what was going to happen in a big way.

After my May ninth mishap I plugged along, using a modified but still defective method. If I hadn’t made money some of the time I might have acquired market wisdom quicker. But I was making enough to enable me to live well. I liked friends and a good time. I was living down the Jersey Coast that summer, like hundreds of prosperous Wall Street men. My winnings were not quite enough to offset both my losses and my living expenses.

I didn’t keep on trading the way I did through stubbornness. I simply wasn’t able to state my own problem to myself, and, of course, it was utterly hopeless to try to solve it. I harp on this topic so much to show what I had to go through before I got to where I could really make money. My old shotgun and BB shot could not do the work of a high-power repeating rifle against big game.

Early that fall I not only was cleaned out again but I was so sick of the game I could no longer beat that I decided to leave New York and try something else some other place. I had been trading since my fourteenth year. I had made my first thousand dollars when I was a kid of fifteen, and my first ten thousand before I was twenty-one. I had made and lost a ten-thousand-dollar stake more than once. In New York I had made thousands and lost them. I got up to fifty thousand dollars and two days later that went. I had no other business and knew no other game. After several years I was back where I began. No—worse, for I had acquired habits and a style of living that required money; though that part didn’t bother me as much as being wrong so consistently.

ENDNOTES

1 Alexander Dana Noyes,

Forty Years of American Finance (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909), 257.

2 Henry Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street (New York: Irving Publishing Company, 1908), 156.

3 Noyes,

Forty Years of American Finance, 286.

4 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 756.

5 Edwin Lefevre, “Boom Days in Wall Street,”

Munsey’s Magazine (1901): 42.

6 New York Times, August 23, 1911, 7.

7 New York Times, January 3, 1917, 12.

8 E. M. Kingsbury, “John W. Gates: The Forgetful Man,”

Everybody’s Magazine 10 (1904): 86.

9 New York Times, December 13, 1917. 22.

12 Kernel of Finance and Politics for Everybody, April 1914.

14 Railroad Age Gazette, August 20, 1915.

15 Edwin Lefevre, “Boom Days in Wall Street,” 40.

16 Peter Wyckoff,

Wall Street and the Stock Markets (Philadelphia: Chilton Book Company, 1972), 18.

17 Edwin Lefevre, “Harriman,”

American Magazine (1907), 117-118.

20 “Vanderbilts’ Great Deal,”

New York Times, October 26, 1900, 1.

21 Maury Klein,

Life and Legend of E. H. Harriman. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 216.

24 New York Times, April 26, 1901, 2.

25 Lefevre, Harriman, 123.

26 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 759

27 Matthew Josephson,

Robber Barons, (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1934), 436.

29 New York Times, May 4, 1901, 3.

30 Josephson,

Robber Barons, 439.

31 New York Times, May 8, 1901. 3.

32 Klein,

Life and Legend of E. H. Harriman, 234.

33 “Night of Excitement in the Waldorf,”

New York Times, May 9, 1901, 1.

35 Noyes,

Forty Years of American Finance, 307.

36 Bernard Baruch, “

Baruch: My Own Story (Cutchogue, New York: Buccaneer Books, 1957), 143-144.

37 Josephson,

Robber Barons, 441.

38 Leonard Louis Levinson,

Wall Street: A Pictorial History (New York: Ziff-David Publishing, 1961), 202.

39 “Disaster and Ruin in Falling Market,”

New York Times, May 10, 1901, 1.

You remember those times? The prosperity of the country was unprecedented. We not only ran into an era of industrial consolidations and combinations of capital that beat anything we had had up to that time, but the public went stock mad.

You remember those times? The prosperity of the country was unprecedented. We not only ran into an era of industrial consolidations and combinations of capital that beat anything we had had up to that time, but the public went stock mad. In previous flush times, I have heard, Wall Street used to brag of two-hundred-and-fifty-thousand-share days, when securities of a par value of twenty-five million dollars changed hands. But in 1901 we had a three-million-share day. Everybody was making money. The steel crowd came to town, a horde of millionaires with no more regard for money than drunken sailors. The only game that satisfied them was the stock market. We had some of the biggest high rollers the Street ever saw: John W. Gates, of ‘Bet-you-a-million’ fame, and his friends, like John A. Drake, Loyal Smith, and the rest; the Reid-Leeds-Moore crowd, who sold part of their Steel holdings and with the proceeds bought in the open market the actual majority of the stock of the great Rock Island system; and Schwab and Frick and Phipps and the Pittsburgh coterie; to say nothing of scores of men who were lost in the shuffle but would have been called great plungers at any other time.

In previous flush times, I have heard, Wall Street used to brag of two-hundred-and-fifty-thousand-share days, when securities of a par value of twenty-five million dollars changed hands. But in 1901 we had a three-million-share day. Everybody was making money. The steel crowd came to town, a horde of millionaires with no more regard for money than drunken sailors. The only game that satisfied them was the stock market. We had some of the biggest high rollers the Street ever saw: John W. Gates, of ‘Bet-you-a-million’ fame, and his friends, like John A. Drake, Loyal Smith, and the rest; the Reid-Leeds-Moore crowd, who sold part of their Steel holdings and with the proceeds bought in the open market the actual majority of the stock of the great Rock Island system; and Schwab and Frick and Phipps and the Pittsburgh coterie; to say nothing of scores of men who were lost in the shuffle but would have been called great plungers at any other time. A fellow could buy and sell all the stock there was. Keene made a market for the U. S. Steel shares.

A fellow could buy and sell all the stock there was. Keene made a market for the U. S. Steel shares. A broker sold one hundred thousand shares in a few minutes. A wonderful time! And there were some wonderful winnings. And no taxes to pay on stock sales! And no day of reckoning in sight.

A broker sold one hundred thousand shares in a few minutes. A wonderful time! And there were some wonderful winnings. And no taxes to pay on stock sales! And no day of reckoning in sight. We know now that both the common and the preferred were being steadily absorbed by the Kuhn-Loeb-Har riman combination.

We know now that both the common and the preferred were being steadily absorbed by the Kuhn-Loeb-Har riman combination. Well, I was long a thousand shares of Northern Pacific common, and held it against the advice of everybody in the office. When it got to about 110 I had thirty points profit, and I grabbed it. It made my balance at my brokers’ nearly fifty thousand dollars, the greatest amount of money I had been able to accumulate up to that time. It wasn’t so bad for a chap who had lost every cent trading in that selfsame office a few months before.

Well, I was long a thousand shares of Northern Pacific common, and held it against the advice of everybody in the office. When it got to about 110 I had thirty points profit, and I grabbed it. It made my balance at my brokers’ nearly fifty thousand dollars, the greatest amount of money I had been able to accumulate up to that time. It wasn’t so bad for a chap who had lost every cent trading in that selfsame office a few months before.