V

The average ticker hound—or, as they used to call him, tape worm—goes wrong, I suspect, as much from overspecialization as from anything else. It means a highly expensive inelasticity. After all, the game of speculation isn’t all mathematics or set rules, however rigid the main laws may be. Even in my tape reading something enters that is more than mere arithmetic. There is what I call the behavior of a stock, actions that enable you to judge whether or not it is going to proceed in accordance with the precedents that your observation has noted. If a stock doesn’t act right don’t touch it; because, being unable to tell precisely what is wrong, you cannot tell which way it is going. No diagnosis, no prognosis. No prognosis, no profit.

It is a very old thing, this of noting the behavior of a stock and studying its past performances. When I first came to New York there was a broker’s office where a Frenchman used to talk about his chart. At first I thought he was a sort of pet freak kept by the firm because they were good-natured. Then I learned that he was a persuasive and most impressive talker. He said that the only thing that didn’t lie because it simply couldn’t was mathematics. By means of his curves he could forecast market movements. Also he could analyse them, and tell, for instance, why Keene did the right thing in his famous Atchison preferred bull manipulation, and later why he went wrong in his Southern Pacific pool.

At various times one or another of the professional traders tried the Frenchman’s system—and then went back to their old unscientific methods of making a living. Their hit-or-miss system was cheaper, they said. I heard that the Frenchman said Keene admitted that the chart was 100 per cent right but claimed that the method was too slow for practical use in an active market.

5.1 Legendary stock operator James R. Keene and market manipulations are two of Lefevre’s favorite topics. The author frequently wrote about both in his regular articles for the Saturday Evening Post and other publications. Lefevre said he believed that Keene, known as the Silver Fox of Wall Street, was “probably the greatest manipulator of stocks in our time” and knew the man well—frequently dropping by his office to chat about the news and the market.

1 Lefevre was not alone in praising Keene. Another op erator, S. V. “Deacon” White, who we will meet later, said that of all the big operators on the exchange, “there never was one the equal of Keene, either for magnitude of operations or for brilliancy of execution.”

2 Keene, for his part, blamed Lefevre for popularizing “that hateful word” of manipulation and labeling him as one of the masters of the dark art. Keene’s issue was the public’s belief that the manipulator was an arch-robber, “a picker of pockets by the thousand,” was misinformed. Like the hedge fund managers and other market insiders of today, manipulators in Livermore’s time were the frequent targets of public ire when amateur traders were duped out of their money.

3

Manipulation, according to Lefevre, “consists in leading the stock market horse—otherwise known as the public—to water, and making him drink; or, as the case might be, in making the public believe the securities it holds are worthless and about to sell on that basis.”

4 Most of the time, manipulation was used to advertise a certain stock by creating an illusion of deep trading interest through action on the ticker machine. Such action piqued the interest of the gambling, bucket-shop types who shunned statistics and earnings trends for the latest hot tip. It allowed insiders to distribute their holdings. Lefevre elaborates in a 1909 article:

A newspaper advertisement, with illuminating statistics, sinks perhaps a thirty-second of an inch into the mind of the “discriminating investor.” But advertising by means of the ticker is another thing. When a man sees a stock going up, up! UP! something goes to the very soul of the greed-stricken man, who visioning to himself a dazzling money-happiness, reaches out quivering fingers, clutches eagerly in the air for the fortune within his grasp. … Men do not read the papers with their very soul; and that is the only way they reach the ticker. The mirage is so real! They buy and later, they curse the “manipulator” who deceived them.

5Manipulation also could be used to accumulate holdings. Two examples are tied to the events that precipitated the May 9, 1901, panic in Northern Pacific Railroad. James J. Hill and J. P. Morgan, after an initial disagreement, decided to pursue the St. Paul railroad and add it to their Great Northern and Northern Pacific empire. Hill stealthily started acquiring shares in the open market to keep the price down. When they had a healthy stake, Hill and Morgan approached the St. Paul insiders—with whom they would own a controlling stake—but were rejected. Then the men turned their attention to the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy line.

This time, Hill loudly proclaimed his interest but revealed his intentions to the railroad’s insiders. In the midst of a stock boom, the action in the Burlington was seen as another run on false rumors that was bound to reverse. Short sellers descended. At one point the price fell 10 points in a day. This increase in selling pressure helped Hill secure as many stock certificates as possible under $200 a share—the price that the Burlington management was demanding from potential acquirers.

6The Southern Pacific pool involved an attempt by Keene in 1901 to convince E. H. Harriman—who controlled the line—to join with him to boost the stock price.

7 Harriman declined. During this time, he preferred to keep dividends low and reinvest earnings to improve and expand his railroads—much to the chagrin of speculators looking for a quick rise.

Keene did not give up as his pool continued to accumulate shares. In 1902, after Harriman reiterated his position, Keene countered by leaking stories to the press and threatening to remove the Southern Pacific’s management unless a 4% dividend was declared.

8 Harriman was irritated, just as today’s executives are by activist investors, and “went gunning for Keene,” according to Lefevre.

9 The battle was settled by a court ruling in 1903, resulting in heavy losses for Keene and his associates.

10Lefevre accounted for Keene’s defeat this way: “Harriman was many things besides a stock operator, while Keene was only the greatest stock speculator that ever lived in the United States. Therefore, the man who was more than a stock speculator won.”

11 In the end, as we will see in Chapter 6, the dividend was raised.

5.2 It is not clear exactly who the “Frenchman” is, but a number of different chart styles were beginning to appear in financial publications around this time. This illustration is an early chart of the Dow Jones Transportation Average.

Then there was one office where a chart of the daily movement of prices was kept. It showed at a glance just what each stock had done for months. By comparing individual curves with the general market curve and keeping in mind certain rules the customers could tell whether the stock on which they got an unscientific tip to buy was fairly entitled to a rise. They used the chart as a sort of complementary tipster. To-day there are scores of commission houses where you find trading charts. They come ready-made from the offices of statistical experts and include not only stocks but commodities.

I should say that a chart helps those who can read it or rather who can assimilate what they read. The average chart reader, however, is apt to become obsessed with the notion that the dips and peaks and primary and secondary movements are all there is to stock speculation. If he pushes his confidence to its logical limit he is bound to go broke. There is an extremely able man, a former partner of a well-known Stock Exchange house, who is really a trained mathematician. He is a graduate of a famous technical school. He devised charts based upon a very careful and minute study of the behaviour of prices in many markets—stocks, bonds, grain, cotton, money, and so on. He went back years and years and traced the correlations and seasonal movements—oh, everything. He used his charts in his stock trading for years. What he really did was to take advantage of some highly intelligent averaging. They tell me he won regularly—until the World War knocked all precedents into a cocked hat. I heard that he and his large following lost millions before they desisted. But not even a world war can keep the stock market from being a bull market when conditions are bullish, or a bear market when conditions are bearish. And all a man needs to know to make money is to appraise conditions.

5.3 Russell Sage was a stock operator who was a close associate of Jay Gould and also worked with James Keene for a time. He was also known as a miser in the company of big spenders, worrying about the cost of his suspenders, and he had a meagerly furnished office.

12 Sage, “who would always go about clad in the plainest of clothes, slightly bent and leaning on his rude cane—in appearance like a retired farmer,” according to a biographer, died leaving a fortune in excess of $70 million.

13Born in 1816 in upstate New York, Sage got his start as an errand boy at a grocery store owned by his brother. By age 20, he became part owner and expanded into the wholesale business. He served in Congress as a member of the Whig party between 1853 and 1857. He made his fi rst appearance in Wall Street in 1861. By 1874, he had his own seat on the New York Stock Exchange.

14Sage was an early innovator in options contracts, actively buying and selling puts and calls on stocks—called “privileges” at the time. This got him into trouble in May 1884, when the market broke badly following the Grant & Ward failure. Sage had written a large number of puts, and his loss was estimated to be roughly $7 million. As early as 8 A.M., the stairway to Sage’s offi ce at 71 Broadway, overlooking the Trinity churchyard, was jammed

with creditors looking to collect on their paper profi ts. Journalist Will Payne describes the scene:

When the door opened there was a bargain-day rush for the cashier’s wicket. Payments were made for a time, with exceeding deliberation; then they stopped. The door was shut in the face of the crowd. One excited creditor undertook to kick it down. A sergeant of police and four patrolmen were required to convince the applicant that money could not be extorted from Mr. Sage by physical violence.

15Helped and advised by Gould, his old friend, Sage found the money needed to redeem his obligations. Having paid dearly for cheap stocks in the midst of panic and losing around $6.5 million, Sage eventually recovered as the market healed.

I didn’t mean to get off the track like that, but I can’t help it when I think of my first few years in Wall Street. I know now what I did not know then, and I think of the mistakes of my ignorance because those are the very mistakes that the average stock speculator makes year in and year out.

After I got back to New York to try for the third time to beat the market in a Stock Exchange house I traded quite actively. I didn’t expect to do as well as I did in the bucket shops, but I thought that after a while I would do much better because I would be able to swing a much heavier line. Yet, I can see now that my main trouble was my failure to grasp the vital difference between stock gambling and stock speculation. Still, by reason of my seven years’ experience in reading the tape and a certain natural aptitude for the game, my stake was earning not indeed a fortune but a very high rate of interest. I won and lost as before, but I was winning on balance. The more I made the more I spent. This is the usual experience with most men. No, not necessarily with easy-money pickers, but with every human being who is not a slave of the hoarding instinct. Some men, like old Russell Sage, have the money-making and the money-hoarding instinct equally well developed, and of course they die disgustingly rich.

Sage—“quiet and simple in his habits,” according to Henry Clews—was a famous accumulator of capital. “He is known as, in one sense, the largest capitalist on Wall Street, inasmuch as he keeps the largest cash balance,” said Clews.

16 In 1903, it was said that only two or three of the greatest banks in New York City had more money “out on call” than Sage had.

17Some interesting trivia from the annals of history, which hearken to eccentric, voluble, media-friendly fund managers of today: Sage would arrive at his office at 9:30 A.M. and leave at 3:30 P.M. An apple and a bowl of crackers with milk constituted his unch.

18 He never drank or smoked. His one apparent luxury was an occasional drive through Central Park. Sage was also quite friendly, freely speaking to reporters. He made a habit, even while talking to someone nearly his own age, of laying a hand on a man’s shoulder and calling him “My son!” half a dozen times in the course of a conversation. He was also a generous provider of lucrative tips on insider information.

19The game of beating the market exclusively interested me from ten to three every day, and after three, the game of living my life. Don’t misunderstand me. I never allowed pleasure to interfere with business. When I lost it was because I was wrong and not because I was suffering from dissipation or excesses. There never were any shattered nerves or rum-shaken limbs to spoil my game. I couldn’t afford anything that kept me from feeling physically and mentally fit. Even now I am usually in bed by ten. As a young man I never kept late hours, because I could not do business properly on insufficient sleep. I was doing better than breaking even and that is why I didn’t think there was any need to deprive myself of the good things of life. The market was always there to supply them. I was acquiring the confidence that comes to a man from a professionally dispassionate attitude toward his own method of providing bread and butter for himself.

The first change I made in my play was in the matter of time. I couldn’t wait for the sure thing to come along and then take a point or two out of it as I could in the bucket shops. I had to start much earlier if I wanted to catch the move in Fullerton’s office. In other words, I had to study what was going to happen; to anticipate stock movements. That sounds asininely commonplace, but you know what

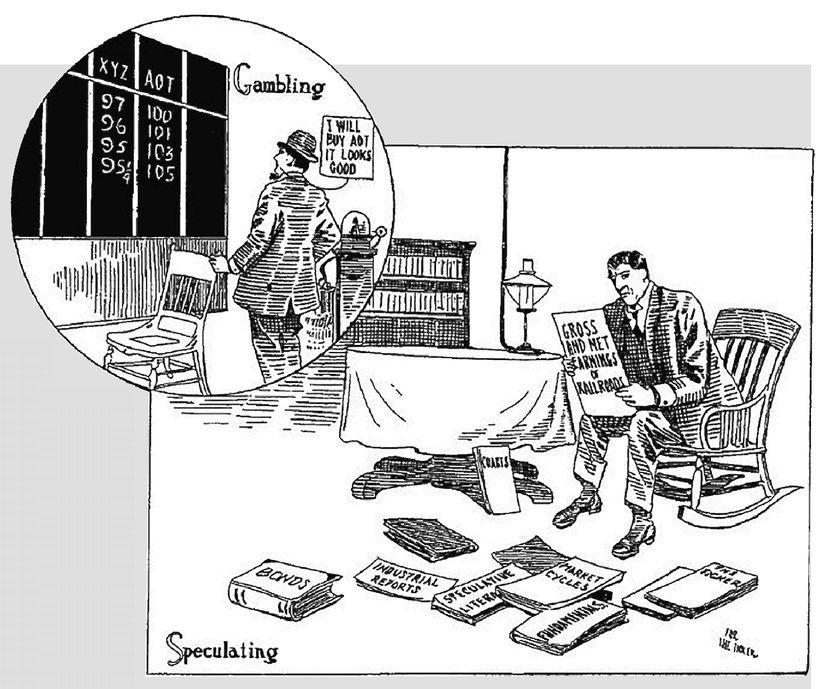

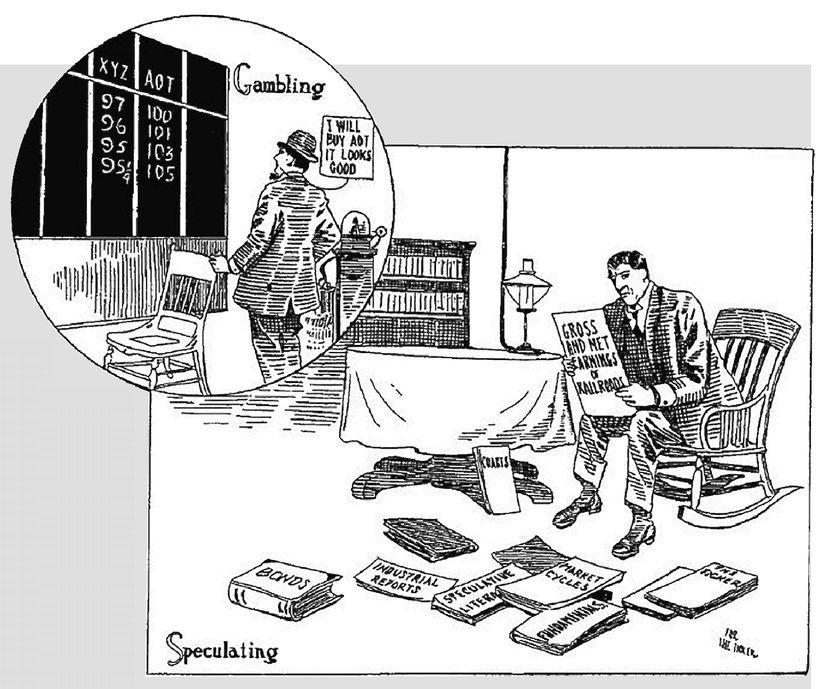

5.4 The distinction between gambling and speculating was an important topic of this period. With the advent of popular participation in the financial markets and the rise of bucket shops, there was a great debate in polite circles about the benefits of these activities. Indeed, the fight against the bucket shops, and the reason they ultimately were shut down, was based on a clear line being drawn between gambling, which offers no larger benefits to society, and speculation, which helps finance business and efficiently sets prices. Lefevre wrote on the subject in 1902:

For every investor in securities there are a hundred speculators; for every man who carefully calculated the value of a stock, and buys and locks his purchase in his strong box, content with the income which his investment yields him, there are a thousand who will buy with the hope of selling soon after at a profit. That is stock-gambling, which is no worse than any other form of gambling, though it is more insidious, since it masquerades as a legitimate business. It gratifies the craving of the gamester; it appears to a man’s reason, to his knowledge of human nature, to his ability to read commercial, agricultural and political conditions; it induces visions of easily acquired wealth.20

For Livermore, it was a graduation of sorts as he climbed the ladder of respectability and potential profits by rounding out his technical trading prowess with fundamental knowledge of economic conditions and earnings trends.

I mean. It was the change in my own attitude toward the game that was of supreme importance to me. It taught me, little by little, the essential difference between betting on fluctuations and anticipating inevitable advances and declines, between gambling and speculating.

I had to go further back than an hour in my studies of the market—which was something I never would have learned to do in the biggest bucket shop in the world. I interested myself in trade reports and railroad earnings and financial and commercial statistics. Of course I loved to trade heavily and they called me the Boy Plunger; but I also liked to study the moves. I never thought that anything was irksome if it helped me to trade more intelligently. Before I can solve a problem I must state it to myself. When I think I have found the solution I must prove I am right. I know of only one way to prove it; and that is, with my own money.

Slow as my progress seems now, I suppose I learned as fast as I possibly could, considering that I was making money on balance. If I had lost oftener perhaps it might have spurred me to more continuous study. I certainly would have had more mistakes to spot. But I am not sure of the exact value of losing, for if I had lost more I would have lacked the money to test out the improvements in my methods of trading.

Studying my winning plays in Fullerton’s office I discovered that although I often was 100 per cent right on the market—that is, in my diagnosis of conditions and general trend—I was not making as much money as my market “rightness” entitled me to. Why wasn’t I?

There was as much to learn from partial victory as from defeat.

For instance, I had been bullish from the very start of a bull market, and I had backed my opinion by buying stocks. An advance followed, as I had clearly foreseen. So far, all very well. But what else did I do? Why, I listened to the elder statesmen and curbed my youthful impetuousness. I made up my mind to be wise and play carefully, conservatively. Everybody knew that the way to do that was to take profits and buy back your stocks on reactions. And that is precisely what I did, or rather what I tried to do; for I often took profits and waited for a reaction that never came. And I saw my stock go kiting up ten points more and I sitting there with my four-point profit safe in my conservative pocket. They say you never grow poor taking profits. No, you don’t. But neither do you grow rich taking a four-point profit in a bull market.

5.5 One of Lefevre’s key motivations for writing Reminis cences was to explain to the public that the stock market was a losing game even for many people who studied, lived, and breathed it. Livermore therefore spends a lot of time providing an ontology of suckerdom. In this passage, he lists various grades of chump: the absolute tyro who bets blindly; the “semisucker” who buys on dips and memorizes a set of rules; the Careful Mike who listens to too many experts and doesn’t develop his own philosophy; and even the semipro who takes profits too quickly in a bull market.

He later explains that the only players who reliably win are ones who first determine if the primary trend is bullish or bearish; buy or short early in the firmly established new trend; sit patiently through any short-term countertrends; and then have a firm philosophy for determining when to exit on a change in the primary trend.

Connecticut-based trader Paul Tudor Jones, who is as close to the Livermore ideal as anyone operating today, recommends using the 200-day average as a guide for the primary trend. Nice and simple. If a stock or market is above the long-term moving average, then stick with it as a long until it falls below. See the chart of defense contrac tor General Dynamics, below, displayed with a 10-month average (dotted line). It started a new bullish trend in April 2003, and exited that trend in mid-2008. Over those five years were several multimonth corrections of 10% or more (shaded), but anyone exiting during those moves would have missed the terrific 150% gain in the stock. This is how Livermore believes you can take full advantage of your best ideas.

Where I should have made twenty thousand dollars I made two thousand. That was what my conservatism did for me. About the time I discovered what a small percentage of what I should have made I was getting I discovered something else, and that is that suckers differ among themselves according to the degree of experience.

The tyro knows nothing, and everybody, including himself, knows it. But the next, or second, grade thinks he knows a great deal and makes others feel that way too. He is the experienced sucker, who has studied—not the market itself but a few remarks about the market made by a still higher grade of suckers. The second-grade sucker knows how to keep from losing his money in some of the ways that get the raw beginner. It is this semisucker rather than the 100 per cent article who is the real all-the-year-round support of the commission houses. He lasts about three and a half years on an average, as compared with a single season of from three to thirty weeks, which is the usual Wall Street life of a first offender. It is naturally the semisucker who is always quoting the famous trading aphorisms and the various rules of the game. He knows all the don’ts that ever fell from the oracular lips of the old stagers—excepting the principal one, which is: Don’t be a sucker!

This semisucker is the type that thinks he has cut his wisdom teeth because he loves to buy on declines. He waits for them. He measures his bargains by the number of points it has sold off from the top. In big bull markets the plain unadulterated sucker, utterly ignorant of rules and precedents, buys blindly because he hopes blindly. He makes most of the money—until one of the healthy reactions takes it away from him at one fell swoop. But the Careful Mike sucker does what I did when I thought I was playing the game intelligently—according to the intelligence of others. I knew I needed to change my bucket-shop methods and I thought I was solving my problem with any change, particularly one that assayed high gold values according to the experienced traders among the customers.

Most—let us call ’em customers—are alike. You find very few who can truthfully say that Wall Street doesn’t owe them money. In Fullerton’s there were the usual crowd. All grades! Well, there was one old chap who was not like the others. To begin with, he was a much older man. Another thing was that he never volunteered advice and never bragged of his winnings. He was a great hand for listening very attentively to the others. He did not seem very keen to get tips—that is, he never asked the talkers what they’d heard or what they knew. But when somebody gave him one he always thanked the tipster very politely. Sometimes he thanked the tipster again—when the tip turned out O.K. But if it went wrong he never whined, so that nobody could tell whether he followed it or let it slide by. It was a legend of the office that the old jigger was rich and could swing quite a line. But he wasn’t donating much to the firm in the way of commissions; at least not that anyone could see. His name was Partridge, but they nicknamed him Turkey behind his back, because he was so thick-chested and had a habit of strutting about the various rooms, with the point of his chin resting on his breast.

5.6 Lefevre comes back to this phrase repeatedly because it was a central theme of Livermore’s trading style. Lefevre believed that there were few techniques more important than trading in sync with the primary trend. In a bull market, he believed, you should trade with the bulls. In a bear market, you should trade with the bears. Later in this chapter he sums it up by stating “The big money was not in the individual fluctuations but in the main movements—that is, not in reading the tape but in sizing up the entire market and its trend.” A little farther along, he adds, “In a bull market your game is to buy and hold until you believe that the bull market is near the end.” The guidance is elegant in its timeless simplicity.

The customers, who were all eager to be shoved and forced into doing things so as to lay the blame for failure on others, used to go to old Partridge and tell him what some friend of a friend of an insider had advised them to do in a certain stock. They would tell him what they had not done with the tip so he would tell them what they ought to do. But whether the tip they had was to buy or to sell, the old chap’s answer was always the same.

The customer would finish the tale of his perplexity and then ask: “What do you think I ought to do?”

Old Turkey would cock his head to one side, contemplate his fellow customer with a fatherly smile, and finally he would say very impressively, “You know, it’s a bull market!”

Time and again I heard him say, “Well, this is a bull market, you know!” as though he were giving to you a priceless talisman wrapped up in a million-dollar accident-insurance policy. And of course I did not get his meaning.

One day a fellow named Elmer Harwood rushed into the office, wrote out an order and gave it to the clerk. Then he rushed over to where Mr. Partridge was listening politely to John Fanning’s story of the time he overheard Keene give an order to one of his brokers and all that John made was a measly three points on a hundred shares and of course the stock had to go up twenty-four points in three days right after John sold out. It was at least the fourth time that John had told him that tale of woe, but old Turkey was smiling as sympathetically as if it was the first time he heard it.

Well, Elmer made for the old man and, without a word of apology to John Fanning, told Turkey, “Mr. Partridge, I have just sold my Climax Motors. My people say the market is entitled to a reaction and that I’ll be able to buy it back cheaper. So you’d better do likewise. That is, if you’ve still got yours.”

Elmer looked suspiciously at the man to whom he had given the original tip to buy. The amateur, or gratuitous, tipster always thinks he owns the receiver of his tip body and soul, even before he knows how the tip is going to turn out.

“Yes, Mr. Harwood, I still have it. Of course!” said Turkey gratefully. It was nice of Elmer to think of the old chap.

“Well, now is the time to take your profit and get in again on the next dip,” said Elmer, as if he had just made out the deposit slip for the old man. Failing to perceive enthusiastic gratitude in the beneficiary’s face Elmer went on: “I have just sold every share I owned!”

From his voice and manner you would have conservatively estimated it at ten thousand shares.

But Mr. Partridge shook his head regretfully and whined, “No! No! I can’t do that!”

“What?” yelled Elmer.

“I simply can’t!” said Mr. Partridge. He was in great trouble.

“Didn’t I give you the tip to buy it?”

“You did, Mr. Harwood, and I am very grateful to you. Indeed, I am, sir. But——”

“Hold on! Let me talk! And didn’t that stock go up seven points in ten days? Didn’t it?”

“It did, and I am much obliged to you, my dear boy. But I couldn’t think of selling that stock.”

“You couldn’t?” asked Elmer, beginning to look doubtful himself. It is a habit with most tip givers to be tip takers.

“No, I couldn’t.”

“Why not?” And Elmer drew nearer.

“Why, this is a bull market!” The old fellow said it as though he had given a long and detailed explanation.

“That’s all right,” said Elmer, looking angry because of his disappointment. “I know this is a bull market as well as you do. But you’d better slip them that stock of yours and buy it back on the reaction. You might as well reduce the cost to yourself.”

“My dear boy,” said old Partridge, in great distress—“my dear boy, if I sold that stock now I’d lose my position; and then where would I be?”

Elmer Harwood threw up his hands, shook his head and walked over to me to get sympathy: “Can you beat it?” he asked me in a stage whisper. “I ask you!”

I didn’t say anything. So he went on: “I give him a tip on Climax Motors. He buys five hundred shares. He’s got seven points’ profit and I advise him to get out and buy ’em back on the reaction that’s overdue even now. And what does he say when I tell him? He says that if he sells he’ll lose his job. What do you know about that?”

“I beg your pardon, Mr. Harwood; I didn’t say I’d lose my job,” cut in old Turkey. “I said I’d lose my position. And when you are as old as I am and you’ve been through as many booms and panics as I have, you’ll know that to lose your position is something nobody can afford; not even John D. Rockefeller. I hope the stock reacts and that you will be able to repurchase your line at a substantial concession, sir. But I myself can only trade in accordance with the experience of many years. I paid a high price for it and I don’t feel like throwing away a second tuition fee. But I am as much obliged to you as if I had the money in the bank. It’s a bull market, you know.” And he strutted away, leaving Elmer dazed.

What old Mr. Partridge said did not mean much to me until I began to think about my own numerous failures to make as much money as I ought to when I was so right on the general market. The more I studied the more I realized how wise that old chap was. He had evidently suffered from the same defect in his young days and knew his own human weaknesses. He would not lay himself open to a temptation that experience had taught him was hard to resist and had always proved expensive to him, as it was to me.

I think it was a long step forward in my trading education when I realized at last that when old Mr. Partridge kept on telling the other customers, “Well, you know this is a bull market!” he really meant to tell them that the big money was not in the individual fluctuations but in the main movements—that is, not in reading the tape but in sizing up the entire market and its trend.

And right here let me say one thing: After spending many years in Wall Street and after making and losing millions of dollars I want to tell you this: It never was my thinking that made the big money for me. It always was my sitting. Got that? My sitting tight! It is no trick at all to be right on the market. You always find lots of early bulls in bull markets and early bears in bear markets. I’ve known many men who were right at exactly the right time, and began buying or selling stocks when prices were at the very level which should show the greatest profit. And their experience invariably matched mine—that is, they made no real money out of it. Men who can both be right and sit tight are uncommon. I found it one of the hardest things to learn. But it is only after a stock operator has firmly grasped this that he can make big money. It is literally true that millions come easier to a trader after he knows how to trade than hundreds did in the days of his ignorance.

The reason is that a man may see straight and clearly and yet become impatient or doubtful when the market takes its time about doing as he figured it must do. That is why so many men in Wall Street, who are not at all in the sucker class, not even in the third grade, nevertheless lose money. The market does not beat them. They beat themselves, because though they have brains they cannot sit tight. Old Turkey was dead right in doing and saying what he did. He had not only the courage of his convictions but the intelligent patience to sit tight.

5.7 Livermore expends a lot of ink trying to drive home the point that it does no good to be right about buying at the start of a bull market, or shorting at the start of a bear market, if you take profits too soon. ”Men who can both be right and sit tight are uncommon,” he says, even for traders who are “not at all in the sucker class.”

The bear market of 2007-2009 served up a prime example. The S&P 500 Index fell below its 10-month average (dotted line) in December 2007, and was ultimately cut in half over the next year and a half. Within that decline were numerous 10%+ countertrend advances that encouraged many shortsellers to cover. But the big money was in sitting tight and letting the entire move play out, covering only on a move back above the 10-month average, which occurred in May 2009.

Livermore laments, in a comment familiar to traders of every era, “Disregarding the big swing and trying to jump in and out was fatal to me. Nobody can catch all the fluctuations.“ His development as a pro reached its apex only once he learned to chill out and not overtrade. “It was never my thinking that made the big money for me,” he says. “It always was my sitting.”

5.8 Despite all of the knowledge that he gained in bucket shops, the stock market and the commodity pits, Livermore blew his entire fortune several times—and ultimately killed himself when he had done it one too many times. Prudent money management was not his strong suit.

The newspaper article shown here was published in the New York Times on February 18, 1915, when he was 38. The article recalls that Livermore’s first big coup came in 1906 when he sold short the Union Pacific and Reading railroads, and made a fortune in the crash of 1907. The following August, it says, he made another “big killing” by shorting cotton in Liverpool, and by 1908 was worth up to $3 million. But it says his luck turned south in August 1908, when he was caught long 60,000 bales of October cotton and the price broke down 67 points, costing him $1 million. This bankruptcy, however, occurred five years later as a result of losses incurred in 1913 and 1914.

Reminiscences was published almost a decade later, so you can see that Livermore was nothing if not resilient, as he accepted every setback as a course in what he calls “a very efficient educational agency.” He survived because he learned to “capitalize” his mistakes, he says, by determining the reason for each loss and adding it to his “schedule of assets.”

Disregarding the big swing and trying to jump in and out was fatal to me. Nobody can catch all the fluctuations. In a bull market your game is to buy and hold until you believe that the bull market is near its end. To do this you must study general conditions and not tips or special factors affecting individual stocks. Then get out of all your stocks; get out for keeps! Wait until you see—or if you prefer, until you think you see—the turn of the market; the beginning of a reversal of general conditions. You have to use your brains and your vision to do this; otherwise my advice would be as idiotic as to tell you to buy cheap and sell dear. One of the most helpful things that anybody can learn is to give up trying to catch the last eighth—or the first. These two are the most expensive eighths in the world. They have cost stock traders, in the aggregate, enough millions of dollars to build a concrete highway across the continent.

Another thing I noticed in studying my plays in Fullerton’s office after I began to trade less unintelligently was that my initial operations seldom showed me a loss. That naturally made me decide to start big. It gave me confidence in my own judgment before I allowed it to be vitiated by the advice of others or even by my own impatience at times. Without faith in his own judgment no man can go very far in this game. That is about all I have learned—to study general conditions, to take a position and stick to it. I can wait without a twinge of impatience. I can see a setback without being shaken, knowing that it is only temporary. I have been short one hundred thousand shares and I have seen a big rally coming. I have figured—and figured correctly—that such a rally as I felt was inevitable, and even wholesome, would make a difference of one million dollars in my paper profits. And I nevertheless have stood pat and seen half my paper profit wiped out, without once considering the advisability of covering my shorts to put them out again on the rally. I knew that if I did I might lose my position and with it the certainty of a big killing. It is the big swing that makes the big money for you.

If I learned all this so slowly it was because I learned by my mistakes, and some time always elapses between making a mistake and realizing it, and more time between realizing it and exactly determining it. But at the same time I was faring pretty comfortably and was very young, so that I made up in other ways. Most of my winnings were still made in part through my tape reading because the kind of markets we were having lent themselves fairly well to my method. I was not losing either as often or as irritatingly as in the beginning of my New York experiences. It wasn’t anything to be proud of, when you think that I had been broke three times in less than two years. And as I told you, being broke is a very efficient educational agency.

I was not increasing my stake very fast because I lived up to the handle all the time. I did not deprive myself of many of the things that a fellow of my age and tastes would want. I had my own automobile and I could not see any sense in skimping on living when I was taking it out of the market. The ticker only stopped Sundays and holidays, which was as it should be. Every time I found the reason for a loss or the why and how of another mistake, I added a brand-new Don’t! to my schedule of assets. And the nicest way to capitalize my increasing assets was by not cutting down on my living expenses. Of course I had some amusing experiences and some that were not so amusing, but if I told them all in detail I’d never finish. As a matter of fact, the only incidents that I remember without special effort are those that taught me something of definite value to me in my trading; something that added to my store of knowledge of the game—and of myself!

ENDNOTES

1 Edwin Lefevre, “Stock Manipulation,”

Saturday Evening Post, March 20, 1909, 33.

2 Edwin Lefevre, “The Unbeatable Game of Stock Speculation.”

Saturday Evening Post, September 4, 1915, 5.

3 Lefevre, “Stock Manipulation.”

4 Edwin Lefevre, “James Robert Keene,”

Cosmopolitan 34 (November 1902- April 1903): 92.

5 Lefevre, “Stock Manipulation,” 35.

7 Maury Klein,

The Life & Legend of E. H. Harriman (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 280-281.

9 Lefevre, “Unbeatable Game of Stock Speculation.”

10 Klein,

Life & Legend of E. H. Harriman,” 281.

11 Lefevre, “Unbeatable Game of Stock Speculation.”

12 William Peter Hamilton,

The Stock Market Barometer (1922), 96.

13 Robert N. Burnett, “Russell Sage,”

Cosmopolitan (1903): 344.

14 Paul Sarnoff,

Russell Sage, the Money King (1965).

15 Will Payne, “The Mere Incident of Failure,”

Everybody’s Magazine 16 (January-June 1907): 24.

16 Henry Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street (New York: Irving Publishing Company, 1908), 671.

17 Burnett, “Russell Sage,” 342.

18 “Little Stories of People and Things,”

Everybody’s Magazine 7 (July- December 1902): 99.

19 Laura Carter Holloway,

Famous American Fortunes and the Men who Have Made Them (1884), 593-596.

20 Lefevre, “James Robert Keene,” 91.

At various times one or another of the professional traders tried the Frenchman’s system—and then went back to their old unscientific methods of making a living. Their hit-or-miss system was cheaper, they said. I heard that the Frenchman said Keene admitted that the chart was 100 per cent right but claimed that the method was too slow for practical use in an active market.

At various times one or another of the professional traders tried the Frenchman’s system—and then went back to their old unscientific methods of making a living. Their hit-or-miss system was cheaper, they said. I heard that the Frenchman said Keene admitted that the chart was 100 per cent right but claimed that the method was too slow for practical use in an active market.