VI

In the spring of 1906 I was in Atlantic City for a short vacation. I was out of stocks and was thinking only of having a change of air and a nice rest. By the way, I had gone back to my first brokers, Harding Brothers, and my account had got to be pretty active. I could swing three or four thousand shares. That wasn’t much more than I had done in the old Cosmopolitan shop when I was barely twenty years of age. But there was some difference between my one-point margin in the bucket shop and the margin required by brokers who actually bought or sold stocks for my account on the New York Stock Exchange.

You may remember the story I told you about that time when I was short thirty-five hundred Sugar in the Cosmopolitan and I had a hunch something was wrong and I’d better close the trade? Well, I have often had that curious feeling. As a rule, I yield to it. But at times I have pooh-poohed the idea and have told myself that it was simply asinine to follow any of these sudden blind impulses to reverse my position. I have ascribed my hunch to a state of nerves resulting from too many cigars or insufficient sleep or a torpid liver or something of that kind. When I have argued myself into disregarding my impulse and have stood pat I have always had cause to regret it. A dozen instances occur to me when I did not sell as per hunch, and the next day I’d go downtown and the market would be strong, or perhaps even advance, and I’d tell myself how silly it would have been to obey the blind impulse to sell. But on the following day there would be a pretty bad drop. Something had broken loose somewhere and I’d have made money by not being so wise and logical. The reason plainly was not physiological but psychological.

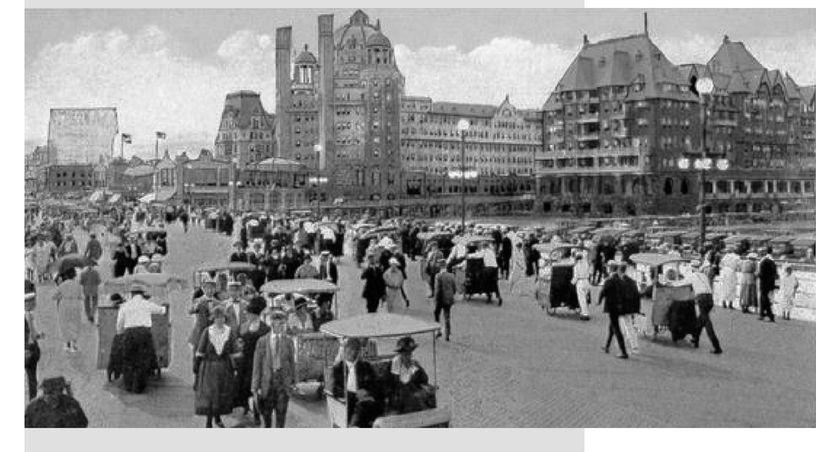

6.1 At the turn of the century, Atlantic City was the seaside resort a short train ride from Manhattan where upper-middle-class urbanites of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania went to relax, enjoy luxury hotels, take in the ocean air, and see a show. In the spring of 1906 when Livermore was visiting, upbeat songs from Broadway musicals like “You’re a Grand Old Flag” by George Cohan were popular, as was piano music like “Frog Legs Rag” by James Scott.

The earliest version of the game “Monopoly” was created around this time, known later to historians as the Progressive Era, by a Quaker woman who used Atlantic City street names to help people understand the evils of property concentration. Streets running parallel to the ocean are named after major bodies of water, such as the Baltic and Pacific, while east-west streets are named after the states. The first decade of the 1900s featured an explosion of luxury hotel construction there, and Livermore would have stayed at one of the grand resorts such as the Marlborough-Blenheim (pictured), the Shelburne, the Traymore, or the Brighton. A wooden boardwalk traversed the front of the oceanfront hotels to prevent guests from tramping sand into lobbies, and there were branches of New York brokerages along the way for those who wished to make a trade while on vacation.

1There is no record of a Harding Brothers brokerage in New York or New Jersey. This name may have been a pseudonym for Lehman Brothers because the firm was active in cotton trading—Livermore’s favorite commodity. In 1906, Lehman was just getting started in underwriting equities, and brought General Cigar (maker of the Ma canudo and Cohiba brands) and Sears, Roebuck & Co. to market that year. In mid-April 1906, the stock market was trading around the same level as at the start of the year, but had risen 115% over the prior two years, giving bulls a lot of confidence.

I want to tell you only about one of them because of what it did for me. It happened when I was having that little vacation in Atlantic City in the spring of 1906.

I had a friend with me who also was a customer of Harding Brothers. I had no interest in the market one way or another and was enjoying my rest. I can always give up trading to play, unless of course it is an exceptionally active market in which my commitments are rather heavy. It was a bull market, as I remember it. The outlook was favorable for general business and the stock market had slowed down but the tone was firm and all indications pointed to higher prices.

One morning after we had breakfasted and had finished reading all the New York morning papers, and had got tired of watching the sea gulls picking up clams and flying up with them twenty feet in the air and dropping them on the hard wet sand to open them for their breakfast, my friend and I started up the Boardwalk. That was the most exciting thing we did in the daytime.

It was not noon yet, and we walked up slowly to kill time and breathe the salt air. Harding Brothers had a branch office on the Boardwalk and we used to drop in every morning and see how they’d opened. It was more force of habit than anything else, for I wasn’t doing anything.

The market, we found, was strong and active. My friend, who was quite bullish, was carrying a moderate line purchased several points lower. He began to tell me what an obviously wise thing it was to hold stocks for much higher prices. I wasn’t paying enough attention to him to take the trouble to agree with him. I was looking over the quotation board, noting the changes—they were mostly advances—until I came to Union Pacific. I got a feeling that I ought to sell it. I can’t tell you more. I just felt like selling it. I asked myself why I should feel like that, and I couldn’t find any reason whatever for going short of UP.

I stared at the last price on the board until I couldn’t see any figures or any board or anything else, for that matter. All I knew was that I wanted to sell Union Pacific and I couldn’t find out why I wanted to.

I must have looked queer, for my friend, who was standing alongside of me, suddenly nudged me and asked, “Hey, what’s the matter?”

“I don’t know,” I answered.

“Going to sleep?” he said.

“No,” I said. “I am not going to sleep. What I am going to do is to sell that stock.” I had always made money following my hunches.

I walked over to a table where there were some blank order pads. My friend followed me. I wrote out an order to sell a thousand Union Pacific at the market and handed it to the manager. He was smiling when I wrote it and when he took it. But when he read the order he stopped smiling and looked at me.

“Is this right?” he asked me. But I just looked at him and he rushed it over to the operator.

“What are you doing?” asked my friend.

“I’m selling it!” I told him.

“Selling what?” he yelled at me. If he was a bull how could I be a bear? Something was wrong.

“A thousand UP,” I said.

“Why?” he asked me in great excitement.

I shook my head, meaning I had no reason. But he must have thought I’d got a tip, because he took me by the arm and led me outside into the hall, where we could be out of sight and hearing of the other customers and rubbering chairwarmers.

“What did you hear?” he asked me.

He was quite excited. UP was one of his pets and he was bullish on it because of its earnings and its prospects. But he was willing to take a bear tip on it at second hand.

“Nothing!” I said.

“You didn’t?” He was skeptical and showed it plainly.

“I didn’t hear a thing.”

“Then why in blazes are you selling?”

“I don’t know,” I told him. I spoke gospel truth.

“Oh, come across, Larry,” he said.

He knew it was my habit to know why I traded. I had sold a thousand shares of Union Pacific. I must have a very good reason to sell that much stock in the face of the strong market.

“I don’t know,” I repeated. “I just feel that something is going to happen.”

“What’s going to happen?”

“I don’t know. I can’t give you any reason. All I know is that I want to sell that stock. And I’m going to let ’em have another thousand.”

I walked back into the office and gave an order to sell a second thousand. If I was right in selling the first thousand I ought to have out a little more.

“What could possibly happen?” persisted my friend, who couldn’t make up his mind to follow my lead. If I’d told him that I had heard UP was going down he’d have sold it without asking me from whom I’d heard it or why. “What could possibly happen?” he asked again.

“A million things could happen. But I can’t promise you that any of them will. I can’t give you any reasons and I can’t tell fortunes,” I told him.

“Then you’re crazy,” he said. “Stark crazy, selling that stock without rime or reason. You don’t know why you want to sell it?”

“I don’t know why I want to sell it. I only know I do want to,” I said. “I want to, like everything.” The urge was so strong that I sold another thousand.

That was too much for my friend. He grabbed me by the arm and said, “Here! Let’s get out of this place before you sell the entire capital stock.”

I had sold as much as I needed to satisfy my feeling, so I followed him without waiting for a report on the last two thousand shares. It was a pretty good jag of stock for me to sell even with the best of reasons. It seemed more than enough to be short of without any reason whatever, particularly when the entire market was so strong and there was nothing in sight to make anybody think of the bear side. But I remembered that on previous occasions when I had the same urge to sell and didn’t do it I always had reasons to regret it.

I have told some of these stories to friends, and some of them tell me it isn’t a hunch but the subconscious mind, which is the creative mind, at work. That is the mind which makes artists do things without their knowing how they came to do them. Perhaps with me it was the cumulative effect of a lot of little things individually insignificant but collectively powerful. Possibly my friend’s unintelligent bullishness aroused a spirit of contradiction and I picked on UP because it had been touted so much. I can’t tell you what the cause or motive for hunches may be. All I know is that I went out of the Atlantic City branch office of Harding Brothers short three thousand Union Pacific in a rising market, and I wasn’t worried a bit.

I wanted to know what price they’d got for my last two thousand shares. So after luncheon we walked up to the office. I had the pleasure of seeing that the general market was strong and Union Pacific higher.

“I see your finish,” said my friend. You could see he was glad he hadn’t sold any.

The next day the general market went up some more and I heard nothing but cheerful remarks from my friend. But I felt sure I had done right to sell UP, and I never get impatient when I feel I am right. What’s the sense? That afternoon Union Pacific stopped climbing, and toward the end of the day it began to go off. Pretty soon it got down to a point below the level of the average of my three thousand shares. I felt more positive than ever that I was on the right side, and since I felt that way I naturally had to sell some more. So, toward the close, I sold an additional two thousand shares.

6.2 By this time in his life, Livermore has come to think of himself as a pro who carefully studied general conditions before making trades, then acted when the odds of success were clearly in his favor. And yet he is fascinated by the notion that he could also act on a hunch, which is a precognitive impulse—a “feeling” rather than a conscious decision evolved from hard data.

Hunches mostly have a bad reputation because they are believed to arise from emotions rather than reason. But that may not be the case. Brett Steenbarger, a Chicago-based clinical psychiatry professor who provides counseling services to traders, has studied the thought processes of thousands of investors in a quest to understand what makes the best ones successful. He believes Livermore’s hunches actually came from his tape-reading experience rather than from his gut.

2After years of looking at stocks’ trading sequences, Livermore had internalized probability outcomes to an extent that did not need to be verbalized. Psychologists call this “implicit learning,” or the ability to know something without knowing you know it. The key is immersion, or repeated concentrated exposure. For someone who doesn’t watch the markets every day, a hunch about a stock would be random and a less-than-50/50 bet. For someone who watches stock movements tick by tick, day after day, as a profession, a hunch about a stock emerges from a deep level of pattern recognition. In this case, then, what Livermore calls following through on a “hunch” was actually a matter of acting intuitively and decisively based on his experience after observing UP quotes at the boardwalk brokerage. It was an important step in his development as a major Wall Street operator.

6.3 In the predawn mist of Wednesday, April 18, 1906, a massive rupture in the San Andreas Fault rocked San Francisco with a 8.3 magnitude earthquake that lasted 42 seconds. The young city withstood the initial tremor remarkably well but was devastated by the fires that followed. The majority of San Francisco’s buildings were made of wood, rather than the brick used in eastern cities at the time, due to its booming lumber trade and proximity to coastal forests.

About 1,000 of the city’s 375,000 residents died as more than four square miles, roughly half the city, burned to the ground. Because the quake damaged water mains, firefighters were stymied.

Property damage estimates ranged from $350 million to $500 million, on which roughly $235 million in insurance policies were held. Losses represented 1.5% of U.S. economic output for the year. Livermore anticipated damage to companies ranging from railroads to banks, and he was right.

Since most buildings had fire insurance but not earthquake insurance, many policyholders set their damaged homes ablaze during the resulting chaos. As you will see later, insurance payouts resulting from this disaster played a huge role in the financial crisis that followed.

3The news spread quickly throughout the United States, eventually affecting the fi nancial markets in London and New York. On April 26, the New York Times reported that the San Francisco disaster resulted in a plunge of 12.5% on the New York Stock Exchange, wiping out $1 billion in market capitalization.

British insurers were particularly hard hit by the disaster, as shares of leading underwriters, such as London & Lancashire, fell as much as 30%. Even before the transcontinental railroad was built in 1869, San Francisco was an international trade hub connecting California’s mining and

There I was, short five thousand shares of UP on a hunch. That was as much as I could sell in Harding’s office with the margin I had up. It was too much stock for me to be short of, on a vacation; so I gave up the vacation and returned to New York that very night. There was no telling what might happen and I thought I’d better be Johnny-on-the-spot. There I could move quickly if I had to.

The next day we got the news of the San Francisco earthquake.

It was an awful disaster. But the market opened down only a couple of points. The bull forces were at work, and the public never is independently responsive to news. You see that all the time. If there is a solid bull foundation, for instance, whether or not what the papers call bull manipulation is going on at the same time, certain news items fail to have the effect they would have if the Street was bearish. It is all in the state of sentiment at the time. In this case the Street did not appraise the extent of the catastrophe because it didn’t wish to. Before the day was over prices came back.

I was short five thousand shares. The blow had fallen, but my stock hadn’t. My hunch was of the first water, but my bank account wasn’t growing; not even on paper.

The friend who had been in Atlantic City with me when I put out my short line in UP. was glad and sad about it.

He told me: “That was some hunch, kid. But, say, when the talent and the money are all on the bull side what’s the use of bucking against them? They are bound to win out.”

“Give them time,” I said. I meant prices. I wouldn’t cover because I knew the damage was enormous and the Union Pacific would be one of the worst sufferers. But it was exasperating to see the blindness of the Street.

“Give ’em time and your skin will be where all the other bear hides are stretched out in the sun, drying,” he assured me.

“What would you do?” I asked him. “Buy UP on the strength of the millions of dollars of damage suffered by the Southern Pacific and other lines? Where are the earnings for dividends going to come from after they pay for all they’ve lost? The best you can say is that the trouble may not be as bad as it is painted. But is that a reason for buying the stocks of the roads chiefly affected? Answer me that.”

agricultural resources to the rest of the world. Most of the exports destined for Europe were financed through the San Francisco offices of British banks. Looking for new sources of revenue, and taking advantage of the pre-1907 California law allowing insurers to underwrite both marine and fire insurance, London’s financial firms decided to diversify at exactly the wrong time. By the turn of the century, nearly half of all fire insurance policies in the city were carried by British firms.

4British banks were caught so off guard because San Francisco’s boom had clouded their judgment. In the days that followed the quake, the New York Times commented, “San Francisco had been so thoroughly free from fire for years” that nearly all the large insurers were very active there. The frequency of earthquakes and the possibility for one natural disaster spurring another were not adequately factored into actuarial tables, a fault that short sellers were able to exploit.

56.4 The slang term “of the first water” was used primarily in this era in a sarcastic sense, as in “he was a swindler of the first water.” But it originated among jewel merchants, who rate the quality and brilliance of diamonds in terms of waters: first water, second water, and so on. First water diamonds are flawless and perfectly clear.

66.5 James Fisk Jr. was a speculator associated with Daniel Drew and Jay Gould. A man of many nicknames, including Prince Erie, Jim Jubilee, and Diamond Jim, Fisk was made famous through his involvement with the Erie War and the gold corner attempt that resulted in the Black Friday panic of 1869. He was also involved with William “Boss” Tweed and the Tammany Hall political machine that corrupted the NewYork politics of the era.

Fisk was one of the most colorful men of the post-Civil War years—an era marked by fantastic economic growth. These were the wild days of capitalism. Regulation was lax. Confidence men, scam artists, prospectors, and speculators mixed with legitimate businessmen, old-money dynasties, and politicians. And yet Fisk stands out above all the other big personalities. Meade Minnigerode brings him to life in a 1927 study:

He was a big, burly, blond creature with “kiss curls” who looked like a butcher, jovial and quick witted, with the manners and gaudy habits of a publican; he was a swindler and a bandit, a destroyer of law and an apostle of fraud; he was a clown in velvet waist-coats and spurious admiral’s uniforms, a fatuous fat man who never grew up, playing with railroads and steamboats, canary birds and ballerinas; his private life was to many a public dismay, his public conduct to some a private scorn; he was, for a while, the most successful, the most conspicuous, the most significant figure in the sinister business world of New York. And to the hundreds of his fellow citizens—thousands, as was shown when his funeral train passed by—he was charitable, light-hearted, open-handed big Jim Fisk; a community which loathed Jay Gould adored him; and when he died they adored him with ballads. The America of the Sixties produced him, and nowhere perhaps, except in the America of 1870, could he have existed.7The son of a country peddler, a common sight before the spread of railroads, Fisk was born in Vermont on April Fool’s Day, 1835. The young man got his start as a hotel waiter before joining the circus as a sweeper, animal keeper, and ticket collector. He returned home to join his father on his peddling trips but soon tired of his conservative style. Fisk wanted more. He wanted gaudy, fl ashy carts pulled by fast horses that could be seen from afar. He wanted to drive through unsuspecting villages at 10 miles an hour, throwing out candy and pennies to the children. Soon Jim was out on his own, according to Minnigerode, as a “jobber in silks, shawls, dress goods, jewelry, silver ware and Yankee notions.”

8 The conspicuous circus man found success with multiple carts covering multiple routes and eventually bought out his father.

9Fisk rose quickly once he turned his attention to big business. Jordan, Marsh & Company, his supplier in Boston, offered him a job in its store. Fisk became a partner as the firm bought and erected several mills to begin manufacturing its own goods. To boost profitability near the start of the Civil War, Fisk illegally broke the southern blockade and started running cotton up through the Confederate lines. At the time, cotton was selling at 12 cents a pound in the South compared to $2 in the North. Fisk became too big, too successful, and was bought out of the partnership. He started his own firm, but it failed.

Finally, in 1864, he went to New York to become a broker. He opened richly festooned offi ces on Broad Street and treated his fellow speculators to the best liquors. But he was new to the Wall Street game; a “lamb fraternizing with wolves,” according to a biographer.

10 He jumped boldly into all the leading stocks but was cut down by a sudden bear raid. He hatched a plan to get another stake: He would

But all my friend said was: “Yes, that listens fine. But I tell you, the market doesn’t agree with you. The tape doesn’t lie, does it?”

“It doesn’t always tell the truth on the instant,” I said.

“Listen. A man was talking to Jim Fisk

a little before Black Friday,

giving ten good reasons why gold ought to go down for keeps. He got so encouraged by his own words that he ended by telling Fisk that he was going to sell a few million. And Jim Fisk just looked at him and said, “Go ahead! Do! Sell it short and invite me to your funeral.’ ”

send a man to London on a fast steamer to short Confederate bonds upon the South’s defeat. With the Atlantic telegraphic cable not yet laid, it took news eight full days to cross the Atlantic on the mail ship. Fisk’s man did it in six and a half and collected a great profit. But in short order, Fisk was ruined again and returned home to Boston.

It was here that he forged a long-lasting friendship with veteran Wall Street operator Daniel Drew. Drew, who was 68 at the time, shared Fisk’s love for the circus since he grew up in Carmel, New York, a common winter camp for traveling acts.

11,12 He became Drew’s broker during the Erie War, which enabled all the events that made Fisk famous.

Fisk would go on to run a railroad, which resulted in an episode of rival trains charging each other on the same disputed piece of track. He paid the debts of the Ninth Regiment of the New York National Guard and was made an honorary colonel. He was admiral of the Narragansett Steamship Company. And he bought Pike’s Opera House, where he would host spectacular shows “in which blondes and brunettes appears on alternate evenings,” according to an ad.

In the end, Fisk met a tragic fate: He was shot dead at age 37 in 1872 by a former business associate and boyfriend of his favored mistress, Helen Mansfield. The New York Times reported his body lay in state with military honors at his opera house before the funeral, and the outpouring of grief outside led to the assembly of one of the largest crowds in the city’s history to date.

13“Yes,” I said; “and if that chap had sold it short, look at the killing he would have made! Sell some UP yourself.”

6.6 Of all the frauds, scams, and other blemishes on America’s financial history, the gold corner attempt of 1869, masterminded by Jay Gould and Jim Fisk, ranks near the top. The plot, which involved political corruption at the highest level of government, initially blew the value of gold sky-high before it crashed, creating such a singular example of misdirected prices that it was still a topic of casual conversation 35 years later.

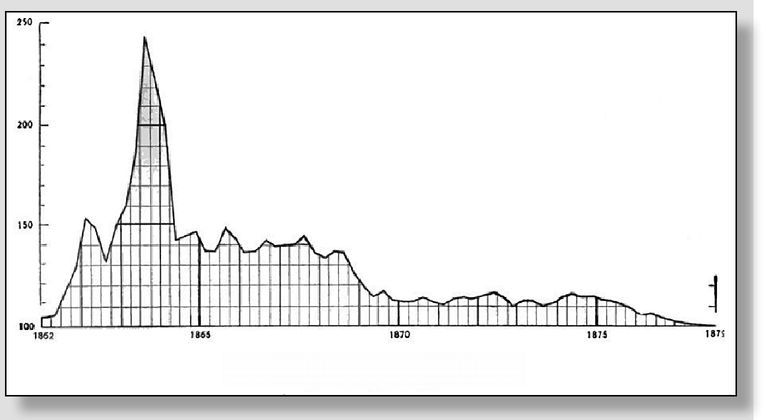

The groundwork for the corner attempt was laid a decade before it occurred in the financing of the Civil War. The government of Abraham Lincoln had issued millions of dollars’ worth of “greenbacks,” or paper money not redeemable into precious metal, to pay its bills. They were backed by bonds sold in Europe. Naturally this new policy of issuing a fiat currency was considered inflationary, so citizens hoarded gold as a store of value. Gold began trading at a premium to the dollar, with the spread fluctuation based on the fortunes of the Union Army. Traders figured that if the North were defeated, greenbacks would become worthless. In contrast, they believed victory by the Union Army would bring the resumption of the gold standard and greenback redemption at face value.

No. VII.—PREMIUM ON GOLD, 1862-1879. (Measured in paper money.)

Volume in the gold market charged higher during the Civil War as traders bet on its outcome, but also for commercial reasons: Foreigners would make payments to U.S. merchants in dollars but demand gold for the settlement of debt. An early exchange was formed in 1862, and soon gold speculators hired agents in both the Union and Confederate camps to alert them of the outcome of battles via private telegraph wires. At one point, Lincoln asked Pennsylvania governor Andrew Curtin: “What do you think of those fellows in Wall Street who are gambling in gold at such a time as this?” Curtin’s terse reply: “For my part, I wish every one of them had his devilish head shot off.”

14The center of the action was the New York Gold Room on New Street, where traders surrounded a fountain in the center of the floor and confronted each other through a water spray. During heated moments, traders reached down to splash water on their faces. Up above was a large mechanical sign displaying the current price of gold. A similar indicator was placed on the building’s facade for the entertainment of those outside. Writing in 1873, William Worthington Fowler described the scene:

The gold room was like a cavern, full of dank and noisome vapors, and the deadly carbonic acid was blended with the fumes of stale smoke and vinous breaths. But the stifling gases engendered in that low-browed cave of evil enchanters, never seemed to depress the energies of the gold-dealers; from “morn to dewy eve” the drooping ceiling and bistre-colored walls reechoed with the sounds of all kinds of voices while an up reared forest of arms was swayed furiously by the storms of a swiftly rising and falling market.

15Gould’s convoluted plan, hatched four years after the Civil War ended, was to boost the price of gold, thereby cheapening the cost of American grain in dollar terms and increasing exports. Not only would Gould profit from his gold holdings as the price rose, but his Wabash Railroad would benefit from higher volumes as more grain was moved to eastern ports for shipment to Europe. The only trouble was that President Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Treasury held some $80 million of gold and could enter the market as a seller if prices rose dramatically. For the scheme to work, Grant had to be convinced that higher gold prices were in the nation’s best interest.

After launching his corner attempt in August 1869, Gould personally appealed to Grant, arguing that elevated gold prices would bring economic prosperity. Figuring that he needed help on the inside, Gould co-opted Abel Corbin, an old speculator who had married Grant’s sister, to lobby the president. But Grant was no simpleton. After listening to the tycoon’s plea and suspecting a con, he told advisors: “It seems to me that there’s a good deal of fiction in all this talk about prosperity. The bubble may as well be pricked one way as another.”

16Gould did not give up, through, and persuaded Corbin and others to try to manipulate the president’s view in new ways. Reported financier Henry Clews in his own account of the affair: “President Grant began to think that the opinion of almost everybody he talked with on this subject was on the same side, and must, therefore, be correct.”

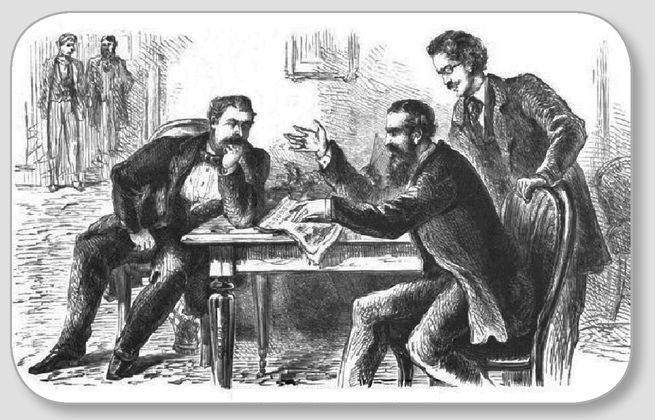

17Gould initially had limited success. He was able to push the price up only two points, to $136.50, between August 31 and September 14 despite his purchases of more than $50 million in gold contracts. Moreover, Gould’s syndicate started to weaken as corrupted brokers broke ranks and began to sell into the advance. Gould needed a big event to scare off the bears, create panic, and send gold higher. He called on celebrated stock operator Jim Fisk for help (see illustration of the meeting).

After being assured everything was in order for the corner, Fisk entered the Gold Room on the morning of September 23 with great flourish, causing the bears to fear for their financial safety and prices to rise to $144.50.

18 Although it seemed as if the plot was proceeding according to plan, a critical error made by Fisk a few days earlier had already doomed the play. He was so eager to make sure Grant didn’t foil their plan that he had Corbin send the president another letter, this time hand-delivered by special messenger, recommending no gold sales. Recounts Clews:

FLOTTING THE GREAT GOLD KING OF

“He read the letter, and had his suspicions at once aroused. He said laconically to the messenger, ‘It is satisfactory; there is no answer.’ Grant then told his sister to instruct her husband to have nothing more to do with the Gould-Fisk gang.”

19Corbin, upon hearing the news, demanded his fee. Gould then realized it was only hours before the New York Treasury would sell gold and break the corner attempt. But to switch to the bear side, he would need to cross Fisk. So while Fisk was buying on Thursday, Gould was secretly selling to him. He said later: “I was a seller of gold that day. … I purchased merely enough to make believe I was a bull.”

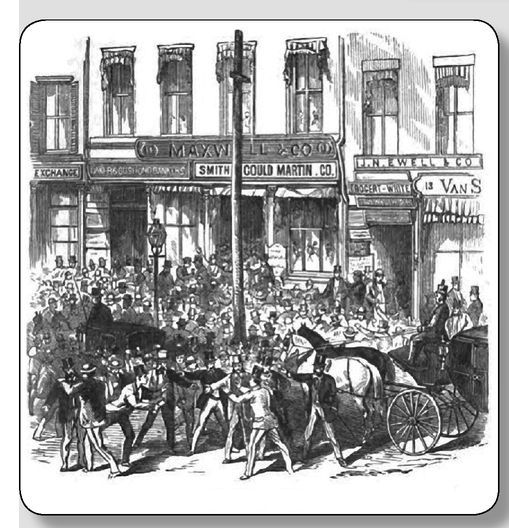

20BLACK FRIDAY.

Pandemonium was unleashed the next day as bears believed that Fisk was buying at any price and predicted gold’s eventual rise to $200 or more. Prices moved to $155 as ambulances carried fainting short sellers to hospitals and crowds started to gather outside Gould’s office (see illustration). In Philadelphia, a clocklike indicator of gold prices could no longer keep pace with the action in New York. Finally, according to one account, “a black flag with a skull and crossbones was thrown over its face.”

21 Prices on the stock exchanges collapsed as speculators sold other securities to help cover their short gold positions. In the final climactic moment around noon, the price reached $160 with no bidders.

Then one of Fisk’s brokers bid $161, an offer that was met with maddening silence. He lifted the bid by fractions, the staccato of each successive bid driving stakes into the hearts of the bears. When he reached $161.375, James Brown, a Scots banker known to represent several European groups, sold $1 million in gold at that price. The Fisk coterie was stunned and lowered the bid to $161. Brown sold again. The corner was over.

The room buzzed that a large bear syndicate organized in Europe was ready to dump tens of millions of dollars in gold on the market as needed to restore order. At around this time, news of Grant’s order to sell the U.S. Treasury’s gold reached inside the trading area courtesy of James Garfield, a future president. In the chaos that ensued, Fisk’s men were still bidding $160 in one corner of the Gold Room while the bid was $135 in another. The afternoon ended with gold at $131.25. Gould had made a fortune, though not exactly the way he intended, and reimbursed Fisk and his men before all went their separate ways.

That session would become known over the years as Black Friday, its facts embellished as the legend grew. A congressional investigation followed, but no one went to jail.

22“Not I! I’m the kind that thrives best on not rowing against wind and tide.”

On the following day, when fuller reports came in, the market began to slide off, but even then not as violently as it should. Knowing that nothing under the sun could stave off a substantial break I doubled up and sold five thousand shares. Oh, by that time it was plain to most people, and my brokers were willing enough. It wasn’t reckless of them or of me, not the way I sized up the market. On the day following, the market began to go for fair. There was the dickens to pay. Of course I pushed my luck for all it was worth. I doubled up again and sold ten thousand shares more. It was the only play possible.

I wasn’t thinking of anything except that I was right—100 per cent right—and that this was a heaven-sent opportunity. It was up to me to take advantage of it. I sold more. Did I think that with such a big line of shorts out, it wouldn’t take much of a rally to wipe out my paper profits and possibly my principal? I don’t know whether I thought of that or not, but if I did it didn’t carry much weight with me. I wasn’t plunging recklessly. I was really playing conservatively. There was nothing that anybody could do to undo the earthquake, was there? They couldn’t restore the crumpled buildings overnight, free, gratis, for nothing, could they? All the money in the world couldn’t help much in the next few hours, could it?

I was not betting blindly. I wasn’t a crazy bear. I wasn’t drunk with success or thinking that because Frisco was pretty well wiped off the map the entire country was headed for the scrap heap. No, indeed! I didn’t look for a panic. Well, the next day I cleaned up. I made two hundred and fifty thousand dollars. It was my biggest winnings up to that time. It was all made in a few days. The Street paid no attention to the earthquake the first day or two. They’ll tell you that it was because the first despatches were not so alarming, but I think it was because it took so long to change the point of view of the public toward the securities markets. Even the professional traders for the most part were slow and shortsighted.

I have no explanation to give you, either scientific or childish. I am telling you what I did, and why, and what came of it. I was much less concerned with the mystery of the hunch than with the fact that I got a quarter of a million out of it. It meant that I could now swing a much bigger line than ever, if or when the time came for it.

That summer I went to Saratoga Springs.

It was supposed to be a vacation for me, but I kept an eye on the market. To begin with, I wasn’t so tired that it bothered me to think about it. And then, everybody I knew up there had or had had an active interest in it. We naturally talked about it. I have noticed that there is quite a difference between talking and trading. Some of these chaps remind you of the bold clerk who talks to his cantankerous employer as to a yellow dog—when he tells you about it.

Harding Brothers had a branch office in Saratoga. Many of their customers were there. But the real reason, I suppose, was the advertising value. Having a branch office in a resort is simply high-class billboard advertising. I used to drop in and sit around with the rest of the crowd. The manager was a very nice chap from the New York office who was there to give the glad hand to friends and strangers and, if possible, to get business. It was a wonderful place for tips—all kinds of tips, horse-race, stock-market, and waiters’. The office knew I didn’t take any, so the manager didn’t come and whisper confidentially in my ear what he’d just got on the q. t. from the New York office. He simply passed over the telegrams, saying, “This is what they’re sending out,” or something of the kind.

Of course I watched the market. With me, to look at the quotation board and to read the signs is one process. My good friend Union Pacific, I no ticed, looked like going up. The price was high, but the stock acted as if it were being accumulated. I watched it a couple of days without trading in it, and the more I watched it the more convinced I became that it was being bought on balance by somebody who was no piker, somebody who not only had a big bank roll but knew what was what. Very clever accumulation, I thought.

6.7 Saratoga Springs in upstate New York, about 45 minutes from Albany, was one of the liveliest resorts in America for high society in the Gilded Age and the first few decades of the 20th century. It was best known for the Saratoga Race Course, which was co-founded in 1863 by Wall Street titan William R. Travers, and continues today as the oldest continuously operated Thoroughbred track in the United States.

23The natural mineral springs, believed to have medicinal powers, were the main draw initially in the 1860s and 1870s, and a Baedeker guidebook published in Europe at the time described the city’s hotels as the largest in the world, with enormous ballrooms and plazas. Vacationers were entertained by street performance artists, traveling circuses, carnival troupes, lecturers, musicians, and tableaux vivants, which were costumed actors posed motionlessly and silently to represent paintings or historical events.

24By the time Livermore would have visited in this passage around 1907, all of these amusements were still plentiful, though it was primarily a place for the Manhattan elite to get away from the heat of the city and bet on the ponies. Of course there were brokerage offices where professional traders like Livermore and Travers rubbed elbows with the dilettante public to gossip and trade ideas without the usual frenetic pace of the stock exchange floor. One of the vacationers’ favorite places to stay was the Grand Union Hotel.

As soon as I was sure of this I naturally began to buy it, at about 160. It kept on acting all hunky, and so I kept on buying it, five hundred shares at a clip. The more I bought the stronger it got, without any spurt, and I was feeling very comfortable. I couldn’t see any reason why that stock shouldn’t go up a great deal more; not with what I read on the tape.

All of a sudden the manager came to me and said they’d got a message from New York—they had a direct wire of course—asking if I was in the office, and when they answered yes, another came saying: “Keep him there. Tell him Mr. Harding wants to speak to him.”

I said I’d wait, and bought five hundred shares more of UP. I couldn’t imagine what Harding could have to say to me. I didn’t think it was anything about business. My margin was more than ample for what I was buying. Pretty soon the manager came and told me that Mr. Ed Harding wanted me on the long-distance telephone.

“Hello, Ed,” I said.

But he said, “What the devil’s the matter with you? Are you crazy?”

“Are you?” I said.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“What do you mean?”

“Buying all that stock.”

“Why, isn’t my margin all right?”

“It isn’t a case of margin, but of being a plain sucker.”

“I don’t get you.”

“Why are you buying all that Union Pacific?”

“It’s going up,” I said.

“Going up, hell! Don’t you know that the insiders are feeding it out to you? You’re just about the easiest mark up there. You’d have more fun losing it on the ponies. Don’t let them kid you.”

“Nobody is kidding me,” I told him. “I haven’t talked to a soul about it.”

But he came back at me: “You can’t expect a miracle to save you every time you plunge in that stock. Get out while you’ve still got a chance,” he said. “It’s a crime to be long of that stock at this level—when these highbinders are shoveling it out by the ton.”

“The tape says they’re buying it,” I insisted.

“Larry, I got heart disease when your orders began to come in. For the love of Mike, don’t be a sucker. Get out! Right away. It’s liable to bust wide open any minute. I’ve done my duty. Good-by!” And he hung up.

Ed Harding was a very clever chap, unusually well-informed and a real friend, disinterested and kind-hearted. And what was even more, I knew he was in position to hear things. All I had to go by, in my purchases of UP., was my years of studying the behaviour of stocks and my perception of certain symptoms which experience had taught me usually accompanied a substantial rise. I don’t know what happened to me, but I suppose I must have concluded that my tape reading told me the stock was being absorbed simply because very clever manipulation by the insiders made the tape tell a story that wasn’t true. Possibly I was impressed by the pains Ed Harding took to stop me from making what he was so sure would be a colossal mistake on my part. Neither his brains nor his motives were to be questioned. Whatever it was that made me decide to follow his advice, I cannot tell you; but follow it, I did.

I sold out all my Union Pacific. Of course if it was unwise to be long of it it was equally unwise not to be short of it. So after I got rid of my long stock I sold four thousand shares short. I put out most of it around 162.

6.8 Upon President McKinley’s assassination in September 1901, Theodore Roosevelt assumed the presidency and began responding to public criticism of the concentration of power and wealth among a small class of capitalists.

25Roosevelt’s first target was the Northern Securities Co. This entity, formed in the aftermath of the May 1901 battle between J. P. Morgan and E. H. Harriman, had the sole purpose of holding shares of the disputed Northern Pacific railroad and the parallel Great Northern system. In February 1902, the government attacked the $400 million corporation as a virtual merger of two competing transcontinental lines, Harriman’s Union Pacific system and Morgan’s Great Northern and Northern Pacific, by which a monopoly of former competitors would be created. In 1904, after an appeal to the Supreme Court, it was found in a 5 to 4 ruling that the mere existence of Northern Securities, and the power it wielded, “constitute a menace to, and a restraint upon, that freedom of commerce which Congress intended to recognize and protect.”

26Harriman, after receiving his share of the Northern Pacific and Great Northern stock, proceeded to sell it to the public at a healthy profit thanks to the booming stock market in 1905 and 1906. By June 30, 1906, Union Pacific held nearly $56 million in cash compared to just $7 million in the previous year. Harriman went east, where his system had no tracks, and bought shares of railways including the New York Central, Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe, and Baltimore & Ohio. Not content with his cash hoard, Harriman had the Union Pacific’s management borrow another $75 million—bringing his total railroad investments between June 1906 and February 1907 to nearly $132 million.

As a result of the dividend income from these investments and increased revenue in its own business, Union Pacific’s net profi t went from $12.6 million in 1900 to nearly $32 million in 1906. Such a dramatic rise in fortune was not ignored by the speculators amassing in brokerage houses across the country: The stock went from a low of $16 1/8 in 1898 to a high of $195 3/8 during 1906. Wall Street was eager for a dividend increase, as Harriman conservatively kept the rate at 4%, despite the jump in earnings, to help fund the expansion of his empire. Eventually, the rate was increased to 5% in 1905 and again to 6% in March 1906.

27Finally, in August, Harriman presented Union Pacific’s board with financial statements showing a surplus of $25 million. Based on this, the dividend was bumped to 10%, and the New York Stock Exchange erupted. On August 18, the New York Times breathlessly reported: “Not since the day for the Northern Pacific ‘corner,’ with its accompanying panic, has the Stock Exchange witnessed so mad a scene as followed the announcement after the market’s opening.” Yet again, shorts were caught in a squeeze and were forced to cover as the “tickers were minutes behind the trading on the floor, quotations of $167½ appearing on the tape in brokerage offices when on the Exchange brokers were fighting to get the stock at $171.”

28Livermore mentions that the directors, namely Harriman, were criticized by the media for initially withholding news of the dividend increase. The decision was made on August 15, but Harriman delayed the release until August 17 to ensure that all directors were briefed and because he wished the announcement be made during New York trading hours. According to Harriman scholar Maury Klein, “More than one observer labeled the episode a throwback to the days of Gould, Fisk, and Drew.”

296.9 One reason that Reminiscences resonates with professional traders is that they have all had the experience of making the mistakes that Livermore makes, both here and elsewhere. In this case, the sin is changing your mind on a position after receiving well-meaning, persuasive but erroneous guidance from a friend or colleague. Being flexible is a valuable trait, but taking advice in the form of a tip without any new underlying data is dangerous. Learning to trust his own instincts and play a lone hand based on his own judgment of fundamental conditions and evidence from trading patterns was a milestone in Livermore’s development—though this was certainly not the last time he would have to take this lesson.

The next day the directors of the Union Pacific Company declared a 10 per cent dividend on the tock.

At first nobody in Wall Street believed it. It was too much like the desperate manœuvre of cornered gamblers. All the newspapers jumped on the directors. But while the Wall Street talent hesitated to act the market boiled over. Union Pacific led, and on huge transactions made a new high-record price. Some of the room traders made fortunes in an hour and I remember later hearing about a rather dull-witted specialist who made a mistake that put three hundred and fifty thousand dollars in his pocket. He sold his seat the following week and became a gentleman farmer the following month.

Of course I realised, the moment I heard the news of the declaration of that unprecedented 10 per cent dividend, that I got what I deserved for disregarding the voice of experience and listening to the voice of a tipster. My own convictions I had set aside for the suspicions of a friend, simply because he was disinterested and as a rule knew what he was doing.

As soon as I saw Union Pacific making new high records I said to myself, “This is no stock for me to be short of.”

All I had in the world was up as margin in Harding’s office. I was neither cheered nor made stubborn by the knowledge of that fact. What was plain was that I had read the tape accurately and that I had been a ninny to let Ed Harding shake my own resolution. There was no sense in recriminations, because I had no time to lose; and besides, what’s done is done. So I gave an order to take in my shorts. The stock was around 165 when I sent in that order to buy in the four thousand UP at the market. I had a three-point loss on it at that figure. Well, my brokers paid 172 and 174 for some of it before they were through. I found when I got my reports that Ed Harding’s kindly intentioned interference cost me forty thousand dollars. A low price for a man to pay for not having the courage of his own convictions! It was a cheap lesson.

I wasn’t worried, because the tape said still higher prices. It was an unusual move and there were no precedents for the action of the directors, but I did this time what I thought I ought to do. As soon as I had given the first order to buy four thousand shares to cover my shorts I decided to profit by what the tape indicated and so I went along. I bought four thousand shares and held that stock until the next morning. Then I got out. I not only made up the forty thousand dollars I had lost but about fifteen thousand besides. If Ed Harding hadn’t tried to save me money I’d have made a killing. But he did me a very great service, for it was the lesson of that episode that, I firmly believe, completed my education as a trader.

It was not that all I needed to learn was not to take tips but follow my own inclination. It was that I gained confidence in myself and I was able finally to shake off the old method of trading. That Saratoga experience was my last haphazard, hit-or-miss operation. From then on I began to think of basic conditions instead of individual stocks. I promoted myself to a higher grade in the hard school of speculation. It was a long and difficult step to take.

ENDNOTES

1 Vicki Gold Levi and Lee Eisenberg,

Atlantic City: 125 Years of Ocean Madness, (Ten Speed Press, 1979).

2 Interview with Brett Steenbarger by Jon Markman, September 25, 2009.

4 The Economist, May 5, 1906, 767.

5 “Enormous Losses of Fire Companies,”

New York Times, April 20, 1906, 4.

6 Betty Kirkpatrick. “Clichés: over 1500 phrases explored and explained.” (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996).

7 Meade Minnigerode,

Certain Rich Men (1927), 192-193.

9 S. A. Swanberg,

Jim Fisk: The Career of an Improbable Rascal (1959), p. 15.

12 Minnigerode,

Certain Rich Men, 201.

13 “The Fisk Murder. Imposing and Elaborate Funeral Services Yesterday”.

New York Times, January 9, 1872.

14 Robert Sobel,

Panic on Wall Street (1968), 136.

15 William Worthington Fowler,

Ten Years in Wall Street (1873), 411-412.

16 Sobel,

Panic on Wall Street, 140.

17 Henry Clews

, Fifty Years in Wall Street (New York: Irving Publishing Company, 1908), 192.

18 Sobel,

Panic on Wall Street, 145.

19 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 196.

20 Kenneth D. Ackerman,

The Gold Ring (1988), 164.

21 Matthew Josephson,

Robber Barons (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1934), 146.

22 Sobel,

Panic on Wall Street, 147-149.

23 “Saratoga Springs: A Historical Portrait.” Timothy A. Holmes and Martha Stonequist. 2000. Arcadia Publishing

24 “First Resorts.” John Sterngrass. 2001. Johns Hopkins University Press.

26 Alexander Dana Noyes,

Forty Years of American Finance (1909), 347.

27 Maury Klein,

Union Pacific: 1894-1969 (2006), 153.

28 “Harriman Dividend Amazes Wall Street,”

New York Times, August 18, 1906, 1.

29 Klein,

Union Pacific, 154.

I had a friend with me who also was a customer of Harding Brothers. I had no interest in the market one way or another and was enjoying my rest. I can always give up trading to play, unless of course it is an exceptionally active market in which my commitments are rather heavy. It was a bull market, as I remember it. The outlook was favorable for general business and the stock market had slowed down but the tone was firm and all indications pointed to higher prices.

I had a friend with me who also was a customer of Harding Brothers. I had no interest in the market one way or another and was enjoying my rest. I can always give up trading to play, unless of course it is an exceptionally active market in which my commitments are rather heavy. It was a bull market, as I remember it. The outlook was favorable for general business and the stock market had slowed down but the tone was firm and all indications pointed to higher prices.

It was an awful disaster. But the market opened down only a couple of points. The bull forces were at work, and the public never is independently responsive to news. You see that all the time. If there is a solid bull foundation, for instance, whether or not what the papers call bull manipulation is going on at the same time, certain news items fail to have the effect they would have if the Street was bearish. It is all in the state of sentiment at the time. In this case the Street did not appraise the extent of the catastrophe because it didn’t wish to. Before the day was over prices came back.

It was an awful disaster. But the market opened down only a couple of points. The bull forces were at work, and the public never is independently responsive to news. You see that all the time. If there is a solid bull foundation, for instance, whether or not what the papers call bull manipulation is going on at the same time, certain news items fail to have the effect they would have if the Street was bearish. It is all in the state of sentiment at the time. In this case the Street did not appraise the extent of the catastrophe because it didn’t wish to. Before the day was over prices came back. The friend who had been in Atlantic City with me when I put out my short line in UP. was glad and sad about it.

The friend who had been in Atlantic City with me when I put out my short line in UP. was glad and sad about it.

a little before Black Friday,

a little before Black Friday, giving ten good reasons why gold ought to go down for keeps. He got so encouraged by his own words that he ended by telling Fisk that he was going to sell a few million. And Jim Fisk just looked at him and said, “Go ahead! Do! Sell it short and invite me to your funeral.’ ”

giving ten good reasons why gold ought to go down for keeps. He got so encouraged by his own words that he ended by telling Fisk that he was going to sell a few million. And Jim Fisk just looked at him and said, “Go ahead! Do! Sell it short and invite me to your funeral.’ ”

It was supposed to be a vacation for me, but I kept an eye on the market. To begin with, I wasn’t so tired that it bothered me to think about it. And then, everybody I knew up there had or had had an active interest in it. We naturally talked about it. I have noticed that there is quite a difference between talking and trading. Some of these chaps remind you of the bold clerk who talks to his cantankerous employer as to a yellow dog—when he tells you about it.

It was supposed to be a vacation for me, but I kept an eye on the market. To begin with, I wasn’t so tired that it bothered me to think about it. And then, everybody I knew up there had or had had an active interest in it. We naturally talked about it. I have noticed that there is quite a difference between talking and trading. Some of these chaps remind you of the bold clerk who talks to his cantankerous employer as to a yellow dog—when he tells you about it. At first nobody in Wall Street believed it. It was too much like the desperate manœuvre of cornered gamblers. All the newspapers jumped on the directors. But while the Wall Street talent hesitated to act the market boiled over. Union Pacific led, and on huge transactions made a new high-record price. Some of the room traders made fortunes in an hour and I remember later hearing about a rather dull-witted specialist who made a mistake that put three hundred and fifty thousand dollars in his pocket. He sold his seat the following week and became a gentleman farmer the following month.

At first nobody in Wall Street believed it. It was too much like the desperate manœuvre of cornered gamblers. All the newspapers jumped on the directors. But while the Wall Street talent hesitated to act the market boiled over. Union Pacific led, and on huge transactions made a new high-record price. Some of the room traders made fortunes in an hour and I remember later hearing about a rather dull-witted specialist who made a mistake that put three hundred and fifty thousand dollars in his pocket. He sold his seat the following week and became a gentleman farmer the following month.