VII

I never hesitate to tell a man that I am bullish or bearish. But I do not tell people to buy or sell any particular stock. In a bear market all stocks go down and in a bull market they go up. I don’t mean of course that in a bear market caused by a war, ammunition shares do not go up. I speak in a general sense. But the average man doesn’t wish to be told that it is a bull or a bear market. What he desires is to be told specifically which particular stock to buy or sell. He wants to get something for nothing. He does not wish to work. He doesn’t even wish to have to think. It is too much bother to have to count the money that he picks up from the ground.

Well, I wasn’t that lazy, but I found it easier to think of individual stocks than of the general market and therefore of individual fluctuations rather than of general movements. I had to change and I did.

People don’t seem to grasp easily the fundamentals of stock trading. I have often said that to buy on a rising market is the most comfortable way of buying stocks. Now, the point is not so much to buy as cheap as possible or go short at top prices, but to buy or sell at the right time. When I am bearish and I sell a stock, each sale must be at a lower level than the previous sale. When I am buying, the reverse is true. I must buy on a rising scale. I don’t buy long stock on a scale down, I buy on a scale up.

Let us suppose, for example, that I am buying some stock. I’ll buy two thousand shares at 110. If the stock goes up to 111 after I buy it I am, at least temporarily, right in my operation, because it is a point higher; it shows me a profit. Well, because I am right I go in and buy another two thousand shares. If the market is still rising I buy a third lot of two thousand shares. Say the price goes to 114. I think it is enough for the time being. I now have a trading basis to work from. I am long six thousand shares at an average of 111¾, and the stock is selling at 114. I won’t buy any more just then. I wait and see. I figure that at some stage of the rise there is going to be a reaction. I want to see how the market takes care of itself after that reaction. It will probably react to where I got my third lot. Say that after going higher it falls back to 112¼, and then rallies. Well, just as it goes back to 113¾ I shoot an order to buy four thousand—at the market of course. Well, if I get that four thousand at 113¾ I know something is wrong and I’ll give a testing order—that is, I’ll sell one thousand shares to see how the market takes it. But suppose that of the order to buy the four thousand shares that I put in when the price was 113¾ I get two thousand at 114 and five hundred at 114½ and the rest on the way up so that for the last five hundred I pay 115½. Then I know I am right. It is the way I get the four thousand shares that tells me whether I am right in buying that particular stock at that particular time—for of course I am working on the assumption that I have checked up general conditions pretty well and they are bullish. I never want to buy stocks too cheap or too easily.

7.2 “Deacon” White was one of the more honorable and upstanding of the Wall Street operators of this era. He was a director for Western Union and the Lackawanna railroad. Henry Clews calls him a “bold, dashing operator in stocks, and in wall Street has met with considerable success. Clews goes on to say: “He is a ready and forcible speaker, full of vim and fire.”

1 Stephen Van Cullen White was born in North Carolina in 1831. His family maintained a small farm, and in the winter months the boy turned to trapping, selling the skins of the animals he captured. He endeavored to become a lawyer and enrolled in the prep school of Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois.

White practiced law until 1865, when he moved to New York, joined the New York Stock Exchange, and worked as a banker and broker. He went bankrupt over a $1 million loss in 1891 but was released from his obligations to trade again with $200,000 after promising to repay his debts in full. In less than a year, he did just that and was readmitted to the NYSE in 1892. He would go on to fail a few more times but always repaid his creditors.

2,

3 In 1886, he was elected to Congress from Brooklyn.

4Although White was a member of Plymouth Church in Brooklyn for many years, this was not the source of his nickname. According to a Munsey’s Magazine profile in January 1894, White said the sobriquet came from a newspaper reporter in a case of mistaken identity.

White was also a poet, renowned Latin translator, classical scholar, and astronomer. He was sympathetic to antislavery advocates and helped build a house for African Americans near his home in Illinois.

5 Despite his many good works, S. V. White was not above making trouble. His most famous exploit was the Lackawanna corner in 1883, called “the only really successful corner in Wall Street since Commodore Vanderbilt’s time.”

6 The operation netted the lawyer $2 million in profits. White also tried to corner corn in 1891 but failed after accumulating 10 million bushels at 48cents. The price went up but dropped before the Deacon could unload his position.

7 In total, though, he was held up as one of the few operators of the time with an ethical backbone.

White crossed paths with a young E. H. Harriman in 1874 while attempting to corner the so-called anthracite stocks. These were railroads responsible for hauling coal. Harriman, a commission broker at the time, noted the rise in these stocks and, according to his biographer, “felt sure someone was trying to monopolize them for speculative purposes. He did not believe that the shares were intrinsically worth the prices that were being offered for them, and when the rise seemed to have reached its culmination, he sold them short.”

8 White was not able to get enough shares to secure the corner, and in the resulting sell-off, Harriman cleared $150,000.

Edwin Lefevre also wrote of White, who died in 1913, in a Saturday Evening Post series warning against stock speculation in 1915. He said:

Of the older men of the generation that preceded [Bet-a-Million] Gates the most picturesque that I have known personally was Stephen Van Cullen White. He tried to beat the game. He made millions—and lost them. He was three times a millionaire and he died poor.…He had a remarkable mind; he distinguished between what was impossible as few other men; he had courage without rashness; patience and genius for striking at the right moment. Over and above all this he had character in the highest degree. Yet he died poor, because the game he tried to beat, beat him.

9

I remember a story I heard about Deacon S. V. White

when he was one of the big operators of the Street. He was a very fine old man, clever as they make them, and brave. He did some wonderful things in his day, from all I’ve heard.

It was in the old days when Sugar was one of the most continuous purveyors of fireworks in the market. H. O. Havemeyer, president of the company, was in the heyday of his power.

I gather from talks with the old-timers that H. O. and his following had all the resources of cash and clever ness necessary to put through successfully any deal in their own stock. They tell me that Havemeyer trimmed more small professional traders in that stock than any other insider in any other stock. As a rule, the floor traders are more likely to thwart the insiders’ game than help it.

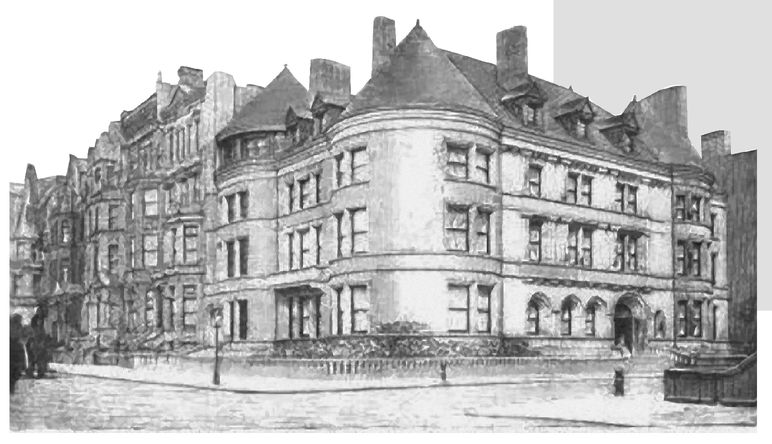

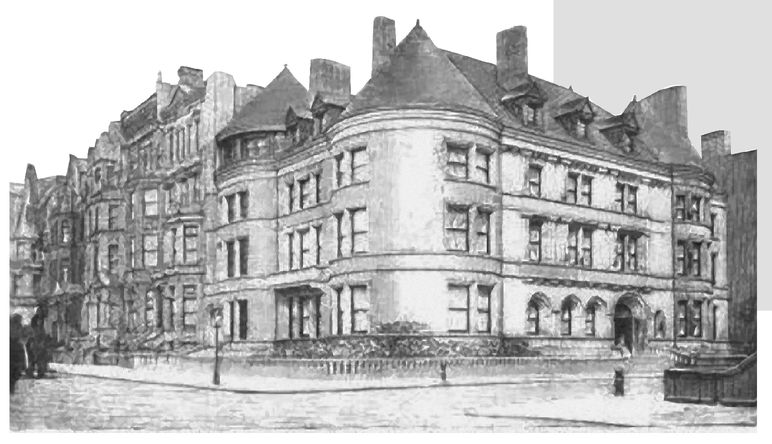

7.2 Henry Osborne Havemeyer founded the American Sugar Refi n-ing Co. in 1891 after inheriting a small refinery business. In the mold of the Standard Oil Trust, a string of consolidations allowed American Sugar to dominate its industry. A profi t margin of 1.1 cents per pound held in all seasons. The stock produced big annual dividend yields: 9% 1892, 22% in 1893, 12% in 1894 through 1899. According to Matthew Josephson in 1934, “H.O. Havemeyer would quietly raise the price of the American breakfast: ‘Who cares for a quarter of a cent a pound?’ he would say blandly.”

10,

11 At left is his Manhattan mansion, where he and his wife amassed a legendary collection of European art.

7.3 The American Sugar Refining Co. was the crown jewel in the network of companies known as the Sugar Trust, all controlled by the Havemeyers. The company operated four refineries in Boston, Jersey City, Brooklyn, and New Orleans. Combined, these four facilities maintained about 70% of the nation’s total capacity.

12 There were only six other refineries, and one of these, in San Francisco, was effectively controlled by the Sugar Trust. By the mid-1890s, the company controlled all but one of these competing facilities and increased its share of the market to 98%. In the years that followed, budding competitors tried to grab some of the profits the Sugar Trust enjoyed as it expanded the margin between raw and refined sugar. Many, such as the United States Sugar Refining Company, never even got a chance to get started. The company was incorporated for the purpose of building a refinery in Camden, New Jersey. Before the plant was ready to open, American Sugar purchased all of its stock; as a result, the plant was never finished.

137.4 This refers to the debate within Congress over free trade with Cuba in 1902 and the reduction or elimination of an import tariff. It was important to the sugar industry because of the potential for fierce competition with the island nation’s tropical climate and ideal growing conditions for sugar cane compared to the less desirable sugar beets grown in the northeastern United States.

Beet sugar producers were represented at the time by Henry Oxnard and the American Beet-Sugar Association. Oxnard said at the time:

Stripped of sentimentality and all extraneous considerations, and reducing the Cuban demands for free or freer sugar to its simplest equation, it is this: Shall the United States, through its agriculturists, produce its raw sugar, and in its factories scattered from the Atlantic to the Pacific, refine its products, or shall it permit foreign lands to export to it the raw material and content itself merely with the refining?

14The sugar beet interests attacked the Sugar Trust and accused it of being in league with foreign producers. From American Sugar’s perspective, additional competition for raw sugar would boost the profitability of its large refining operations. The Sugar Trust was also accused of controlling the Cuban sugar crop.

15In the end, the Congress passed the Reciprocity Treaty of 1903, which granted Cuba a 20% discount on full sugar import tariffs. In the years that followed, Cuban producers came to be the major supplier of sugar to the United States: From less than 15% in 1900, Cuba’s share of the U.S. sugar market fluctuated between 50% and 70% during the 1920s.

16One day a man who knew Deacon White rushed into the office all excited and said, “Deacon, you told me if I ever got any good information to come to you at once with it and if you used it you’d carry me for a few hundred shares.” He paused for breath and for confirmation.

The deacon looked at him in that meditative way he had and said, “I don’t know whether I ever told you exactly that or not, but I am willing to pay for information that I can use.”

“Well, I’ve got it for you.”

“Now, that’s nice,” said the deacon, so mildly that the man with the info swelled up and said, “Yes, sir, deacon.” Then he came closer so nobody else would hear and said, “H. O. Havemeyer is buying Sugar.”

“Is he?” asked the deacon quite calmly.

It peeved the informant, who said impressively: “Yes, sir. Buying all he can get, deacon.”

“My friend, are you sure?” asked old S. V.

“Deacon, I know it for a positive fact. The old inside gang are buying all they can lay their hands on. It’s got something to do with the tariff

and there’s going to be a killing in the common. It will cross the preferred. And that means a sure thirty points for a starter.”

“D’ you really think so?” And the old man looked at him over the top of the old-fashioned silver-rimmed spectacles that he had put on to look at the tape.

“Do I think so? No, I don’t think so; I know so. Absolutely! Why, deacon, when H. O. Havemeyer and his friends buy Sugar as they’re doing now they’re never satisfied with anything less than forty points net. I shouldn’t be surprised to see the market get away from them any minute and shoot up before they’ve got their full lines. There ain’t as much of it kicking around the brokers’ offices as there was a month ago.”

“He’s buying Sugar, eh?” repeated the deacon absently.

“Buying it? Why, he’s scooping it in as fast as he can without putting up the price on himself.”

“So?” said the deacon. That was all.

But it was enough to nettle the tipster, and he said, “Yes, sir-ree! And I call that very good information. Why, it’s absolutely straight.”

“Is it?”

“Yes; and it ought to be worth a whole lot. Are you going to use it?”

“Oh, yes. I’m going to use it.”

“When?” asked the information bringer suspiciously.

“Right away.” And the deacon called: “Frank!” It was the first name of his shrewdest broker, who was then in the adjoining room.

“Yes, sir,” said Frank.

“I wish you’d go over to the Board and sell ten thousand Sugar.”

“Sell?” yelled the tipster. There was such suffering in his voice that Frank, who had started out at a run, halted in his tracks.

“Why, yes,” said the deacon mildly.

“But I told you H. O. Havemeyer was buying it!”

“I know you did, my friend,” said the deacon calmly; and turning to the broker: “Make haste, Frank!”

The broker rushed out to execute the order and the tipster turned red.

“I came in here,” he said furiously, “with the best information I ever had. I brought it to you because I thought you were my friend, and square. I expected you to act on it——”

“I am acting on it,” interrupted the deacon in a tranquillising voice.

7.5 The notion that sugar could be the basis for an exciting stock that traded with great volatility in large size is hard to grasp today. But the reality is that sugar was one of the most important crops in the development of industry and world trade in the seventeenth through early twentieth centuries, and has a bittersweet history.

While sugar was first grown commercially in India, and then dispersed through Europe and the rest of the world by Muslim refiners and traders, it was not cultivated on a massive scale until the opening of the New World by European merchant farmers. Most of the slave trade in the 1700s and 1800s was focused on transporting Africans to the Caribbean and South America to work sugar cane fields on plantations graced with the tremendous amount of rainfall the crop requires. On the plus side, the industrial base of the Caribbean and Brazil was built to refine sugar and its derivatives.

By the early twentieth century, sugar had already become inexpensive enough to satisfy the sweet tooth of the middle class at the breakfast table, providing the Havemeyer clan with its billions—but new commercial food products and techniques would soon bring sugar to the masses in the form of candy, cookies, and soda pop, ramping demand exponentially.

In 1900, Milton S. Hershey created the fi rst milk chocolate bar, shown here, in his home town of Derry Church, Pennsylvania, which would later be renamed Hershey. In 1902, the National Biscuit Co., later renamed Nabisco, created its iconic circus wagon box for animal crackers, with a string attached so it could be hung on Christmas trees. Caleb Bradham, a North Carolina pharmacist, invented a competitor to Coca-Cola for sale in his drugstore in 1893, fl avored with vanilla and pepsin, but didn’t trademark the name for the commercial distribution of Pepsi-Cola until 1903. In 1904, the ice cream cone was invented at the St. Louis World’s Fair. In 1905, Frank Epperson invented the Popsicle, though it was originally named the Epsicle. Around 1909, Nabisco debuted the Oreo cookie. And by 1910, the government estimated that there were over 80,000 soda fountains in the United States.

Trading in the commodity was tough even for insiders. Pepsi-Cola went bankrupt in 1923 after Bradham gambled on a big increase in the cost of sugar during World War 1. Prices actually fell in value, leaving Pepsi with an overpriced sugar inventory that crippled the fi rm. It was purchased out of bankruptcy and revived in the Depression with branding focused on low cost.

In the background all the while were traders like the White and Livermore providing liquidity for Sugar’s shares.

“But I told you H. O. and his gang were buying!”

“That’s right. I heard you.”

“Buying! Buying! I said buying!” shrieked the tipster.

“Yes, buying! That is what I understood you to say,” the deacon assured him. He was standing by the ticker, looking at the tape.

“But you are selling it.”

“Yes; ten thousand shares.” And the deacon nodded. “Selling it, of course.” 7.5

He stopped talking to concentrate on the tape and the tipster approached to see what the deacon saw, for the old man was very foxy. While he was looking over the deacon’s shoulder a clerk came in with a slip, obviously the report from Frank. The deacon barely glanced at it. He had seen on the tape how his order had been executed.

It made him say to the clerk, “Tell him to sell another ten thousand Sugar.”

“Deacon, I swear to you that they really are buying the stock!”

“Did Mr. Havemeyer tell you?” asked the deacon quietly.

“Of course not! He never tells anybody anything. He would not bat an eyelid to help his best friend make a nickel. But I know this is true.”

“Do not allow yourself to become excited, my friend.” And the deacon held up a hand. He was looking at the tape. The tip-bringer said, bitterly:

“If I had known you were going to do the opposite of what I expected I’d never have wasted your time or mine. But I am not going to feel glad when you cover that stock at an awful loss. I’m sorry for you, deacon. Honest! If you’ll excuse me I’ll go elsewhere and act on my own information.”

“I’m acting on it. I think I know a little about the market; not as much, perhaps, as you and your friend H. O. Havemeyer, but still a little. What I am doing is what my experience tells me is the wise thing to do with the information you brought me. After a man has been in Wall Street as long as I have he is grateful for anybody who feels sorry for him. Remain calm, my friend.”

The man just stared at the deacon, for whose judgment and nerve he had great respect.

Pretty soon the clerk came in again and handed a report to the deacon, who looked at it and said: “Now tell him to buy thirty thousand Sugar. Thirty thousand!”

The clerk hurried away and the tipster just grunted and looked at the old gray fox.

“My friend,” the deacon explained kindly, “I did not doubt that you were telling me the truth as you saw it. But even if I had heard H. O. Havemeyer tell you himself, I still would have acted as I did. For there was only one way to find out if anybody was buying the stock in the way you said H. O. Havemeyer and his friends were buying it, and that was to do what I did. The first ten thousand shares went fairly easily. It was not quite conclusive. But the second ten thousand was absorbed by a market that did not stop rising. The way the twenty thousand shares were taken by somebody proved to me that somebody was in truth willing to take all the stock that was offered. It doesn’t particularly matter at this point who that particular somebody may be. So I have covered my shorts and am long ten thousand shares, and I think that your information was good as far as it went.”

“And how far does it go?” asked the tipster.

“You have five hundred shares in this office at the average price of the ten thousand shares,” said the deacon. “Good day, my friend. Be calm the next time.”

“Say, deacon,” said the tipster, “won’t you please sell mine when you sell yours? I don’t know as much as I thought I did.”

That’s the theory. That is why I never buy stocks cheap. Of course I always try to buy effectively—in such a way as to help my side of the market. When it comes to selling stocks, it is plain that nobody can sell unless somebody wants those stocks.

If you operate on a large scale you will have to bear that in mind all the time. A man studies conditions, plans his operations carefully and proceeds to act. He swings a pretty fair line and he accumulates a big profit—on paper. Well, that man can’t sell at will. You can’t expect the market to absorb fifty thousand shares of one stock as easily as it does one hundred. He will have to wait until he has a market there to take it. There comes the time when he thinks the requisite buying power is there. When that opportunity comes he must seize it. As a rule he will have been waiting for it. He has to sell when he can, not when he wants to. To learn the time, he has to watch and test. It is no trick to tell when the market can take what you give it. But in starting a movement it is unwise to take on your full line unless you are convinced that conditions are exactly right. Remember that stocks are never too high for you to begin buying or too low to begin selling. But after the initial transaction, don’t make a second unless the first shows you a profit. Wait and watch. That is where your tape reading comes in—to enable you to decide as to the proper time for beginning. Much depends upon beginning at exactly the right time. It took me years to realize the importance of this. It also cost me some hundreds of thousands of dollars.

I don’t mean to be understood as advising persistent pyramiding. A man can pyramid and make big money that he couldn’t make if he didn’t pyramid; of course. But what I meant to say was this: Suppose a man’s line is five hundred shares of stock. I say that he ought not to buy it all at once; not if he is speculating. If he is merely gambling the only advice I have to give him is, don’t!

Suppose he buys his first hundred, and that promptly shows him a loss. Why should he go to work and get more stock? He ought to see at once that he is in wrong; at least temporarily.

7.6 Livermore reveals some tradecraft here, explaining with a colorful story that it’s not enough to simply take a bullish tip from a source: It’s important to test the idea against the market. If there’s ample demand for the stock when it’s first sold, or shorted, then there’s probably enough buying power to drive it higher. But to take a recommendation blindly leaves the tip taker in the position of being the lowest level of sucker, or at best a gambler.

He also stresses two other big themes: Stocks are never too high to be bought or too low to be shorted, and a well- trained speculator never purchases the full amount that he wishes to apportion to a new position at the start of his buying.

After much trial and error in the early part of his career, Livermore has discovered that even if a stock like Sugar has already doubled in the past six months it can double again—but you won’t know exactly how it trades, and how much money to put into it, until you own the shares yourself and become more intimately familiar with its volatility. If your first purchase results in a loss, he believes, you’re not early, you’re just wrong—so don’t add more until, by rising, it shows that you are right. If your first purchase results in a gain, he recommends, then add more as it rises and it fulfills your expectations.

ENDNOTES

1 Henry Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street (New York, Irving Publishing Company, 1908), 661-662.

2 The Cyclopædia of American Biography, vol. 5 (1897), 478.

3 John W. Leonard, “Albert Nelson Marquis,”

Who’s Who in America (1901- 1902), 1225.

4 Edward G. Riggs, Charles J. Rosebault, and C. J. Fitzgerald, “Wall Street,”

Munsey’s Magazine (January, 1894): 360.

7 “Banking and Financial News,”

Banker’s Magazine 65 (July-December 1902): 1030.

8 George Kennan,

E. H. Harriman (1922), 17.

9 Edwin Lefevre, “The Unbeatable Game of Stock Speculation,”

Saturday Evening Post, September 4, 1915, 29.

10 Matthew Josephson,

The Robber Barons (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1934), 381.

12 Eliot Jones,

The Trust Problem in the United States (1921), 93.

14 “The Cuban Tariff Hearings,”

Public Opinion, January 30, 1902, 4.

15 Public Opinion, May 1, 1902, 1.

16 Alan Dye,

Cuban Sugar in the Age of Mass Production (1998), 53.

when he was one of the big operators of the Street. He was a very fine old man, clever as they make them, and brave. He did some wonderful things in his day, from all I’ve heard.

when he was one of the big operators of the Street. He was a very fine old man, clever as they make them, and brave. He did some wonderful things in his day, from all I’ve heard. I gather from talks with the old-timers that H. O. and his following had all the resources of cash and clever ness necessary to put through successfully any deal in their own stock. They tell me that Havemeyer trimmed more small professional traders in that stock than any other insider in any other stock. As a rule, the floor traders are more likely to thwart the insiders’ game than help it.

I gather from talks with the old-timers that H. O. and his following had all the resources of cash and clever ness necessary to put through successfully any deal in their own stock. They tell me that Havemeyer trimmed more small professional traders in that stock than any other insider in any other stock. As a rule, the floor traders are more likely to thwart the insiders’ game than help it.

and there’s going to be a killing in the common. It will cross the preferred. And that means a sure thirty points for a starter.”

and there’s going to be a killing in the common. It will cross the preferred. And that means a sure thirty points for a starter.”