VIII

The Union Pacific incident in Saratoga in the summer of 1906 made me more independent than ever of tips and talk—that is, of the opinions and surmises and suspicions of other people, however friendly or however able they might be personally. Events, not vanity, proved for me that I could read the tape more accurately than most of the people about me. I also was better equipped than the average customer of Harding Brothers in that I was utterly free from speculative prejudices. The bear side doesn’t appeal to me any more than the bull side, or vice versa. My one steadfast prejudice is against being wrong.

Even as a lad I always got my own meanings out of such facts as I observed. It is the only way in which the meaning reaches me. I cannot get out of facts what somebody tells me to get. They are my facts, don’t you see? If I believe something you can be sure it is because I simply must. When I am long of stocks it is because my reading of conditions has made me bullish. But you find many people, reputed to be intelligent, who are bullish because they have stocks. I do not allow my possessions—or my prepossessions either—to do any thinking for me. That is why I repeat that I never argue with the tape. To be angry at the market because it unexpectedly or even illogically goes against you is like getting mad at your lungs because you have pneumonia.

I had been gradually approaching the full realization of how much more than tape reading there was to stock speculation. Old man Partridge’s insistence on the vital importance of being continuously bullish in a bull market doubtless made my mind dwell on the need above all other things of determining the kind of market a man is trading in. I began to realize that the big money must necessarily be in the big swing. Whatever might seem to give a big swing its initial impulse, the fact is that its continuance is not the result of manipulation by pools or artifice by financiers, but depends upon basic conditions. And no matter who opposes it, the swing must inevitably run as far and as fast and as long as the impelling forces determine.

After Saratoga I began to see more clearly—perhaps I should say more maturely—that since the entire list moves in accordance with the main current there was not so much need as I had imagined to study individual plays or the behaviour of this or the other stock. Also, by thinking of the swing a man was not limited in his trading. He could buy or sell the entire list. In certain stocks a short line is dangerous after a man sells more than a certain percentage of the capital stock, the amount depending upon how, where and by whom the stock is held. But he could sell a million shares of the general list—if he had the price—without the danger of being squeezed. A great deal of money used to be made periodically by insiders in the old days out of the shorts and their carefully fostered fears of corners and squeezes.

Obviously the thing to do was to be bullish in a bull market and bearish in a bear market. Sounds silly, doesn’t it? But I had to grasp that general principle firmly before I saw that to put it into practice really meant to anticipate probabilities. It took me a long time to learn to trade on those lines. But in justice to myself I must remind you that up to then I had never had a big enough stake to speculate that way. A big swing will mean big money if your line is big, and to be able to swing a big line you need a big balance at your broker’s.

I always had—or felt that I had—to make my daily bread out of the stock market. It interfered with my efforts to increase the stake available for the more profitable but slower and therefore more immediately expensive method of trading on swings.

But now not only did my confidence in myself grow stronger but my brokers ceased to think of me as a sporadically lucky Boy Plunger. They had made a great deal out of me in commissions, but now I was in a fair way to become their star customer and as such to have a value beyond the actual volume of my trading. A customer who makes money is an asset to any broker’s office.

The moment I ceased to be satisfied with merely studying the tape I ceased to concern myself exclusively with the daily fluctuations in specific stocks, and when that happened I simply had to study the game from a different angle. I worked back from the quotation to first principles; from price fluctuations to basic conditions.

Of course I had been reading the daily dope

regularly for a long time. All traders do. But much of it was gos sip, some of it deliberately false, and the rest merely the personal opinion of the writers. The reputable weekly reviews when they touched upon underlying conditions were not entirely satisfactory to me. The point of view of the financial editors was not mine as a rule. It was not a vital matter for them to marshal their facts and draw their conclusions from them, but it was for me. Also there was a vast difference in our appraisal of the element of time. The analysis of the week that had passed was less important to me than the forecast of the weeks that were to come.

8.1 Livermore kept abreast of political and market conditions by being a voracious reader of trade and fi nancial publications. Many of the resources available more than 100 years ago would be familiar to modern investors, including the New York Times, the Economist, and the Wall Street Journal. But many popular publications of this era have passed into history, most prominently the Ticker and Investment Digest, the Magazine of Wall Street, the Kernel of Finance and Politics for Everybody, Dun’s Review, and the excellent Commercial & Financial Chronicle, which failed in the aftermath of the Black Monday crash of 1987.

For years I had been the victim of an unfortunate combination of inexperience, youth and insufficient capital. But now I felt the elation of a discoverer. My new attitude toward the game explained my repeated failures to make big money in New York. But now with adequate resources, experience and confidence, I was in such a hurry to try the new key that I did not notice that there was another lock on the door—a time lock! It was a perfectly natural oversight. I had to pay the usual tuition—a good whack per each step forward.

I studied the situation in 1906 and I thought that the money outlook was particularly serious. 8.2 Much actual wealth the world over had been destroyed. Everybody must sooner or later feel the pinch, and therefore nobody would be in position to help anybody. It would not be the kind of hard times that comes from the swapping of a house worth ten thousand dollars for a carload of race horses worth eight thousand dollars. It was the complete destruction of the house by fire and of most of the horses by a railroad wreck. It was good hard cash that went up in cannon smoke in the Boer War, and the millions spent for feeding nonproducing soldiers in South Africa meant no help from British investors as in the past. Also, the earthquake and the fire in San Francisco and other disasters touched everybody—manufacturers, farmers, merchants, labourers and millionaires. The railroads must suffer greatly. I figured that nothing could stave off one peach of a smash. Such being the case there was but one thing to do—sell stocks!

8.2 Livermore refers here to the flow and quantity of gold specie available to fund economic activity and investment. Between 1870 and 1914, much of the developed world was on the gold standard, in which paper currency was redeemable into measures of gold on demand. Therefore, money supply growth was limited to the success of gold mining operations and the cross-border flow of gold reserves. In short, countries shared a finite supply of money.

Simple economics controlled the supply of gold stocks. As an example, a sudden outflow of gold would cause a tightening of the money supply, a rise in interest rates, and a reduction in the general price level as the economy slowed. The increased competitiveness of cheap exports and more attractive interest rates would cause gold to flow back into the country and restore the previous equilibrium. Central bankers of the period operated according to these rules, expanding and contracting the money supply and raising or lowering interest rates accordingly.

With large policy exposures to the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, foreign insurers, especially British firms, began sending gold to California to pay off claims. Between late April and May 1906 nearly $50 million of gold poured into the United States from Germany, France, the Netherlands, and England (whose contribution alone amounted to $30 million). Of these flows, 80% went directly to San Francisco. The city that staked its existence and prosperity on the mining and export of gold now was receiving huge amounts of gold back with which to replenish ashen wreckage.

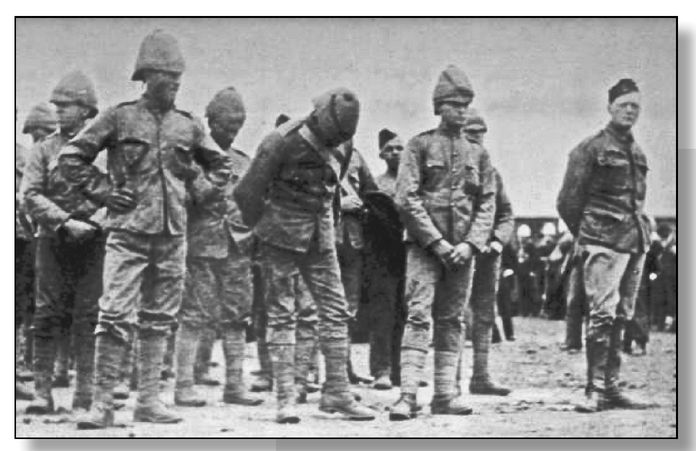

1Other factors contributed to unusual supply constraints on gold during this period, which increased the price of money. The first was the Boer War that Livermore mentions. Officially known as the Second Boer War, and waged between 1899 and 1902, it was a conflict fought between the British Empire and two independent Boer republics in present-day South Africa upon the discovery of massive gold deposits. Not only was money put to nonproductive use buying arms and other war supplies, but full gold production did not resume until 1905—dampening the influx of new capital at a time of feverish speculation and capital investment. (Photo on page 119 shows London Morning Post war correspondent Winston Churchill, far right, after being captured by Boers in 1899 and held in Pretoria. His heroism during an ambush of a British army unit he was covering helped launch his political career.)

Another development was the outbreak of war between Russia and Japan in 1904, following a previous conflict between 1884 and 1885 over competing claims on Manchuria and Korea. To fund the war, both Japan and Russia tapped the credit markets of neutral nations—Russian bonds were floated in Paris while Japanese issues were sold in London and New York. Overall, historian Alexander Dana Noyes estimated that neutral markets spent roughly $1 billion on “pure waste; it does not return to the channels of industry, and it diminishes the world’s reserve of capital.”

Before 1913, the United States lacked a central bank that could temper the economic volatility associated with gold flows. Indeed, historians argue that unusual gold movements were responsible for most financial crises and economic downturns in the pre-Federal Reserve era. Complications in the United States associated with gold flows set the stage for the defining moment of Livermore’s early trading career: the Panic of 1907.

I told you I had already observed that my initial transaction, after I made up my mind which way I was going to trade, was apt to show me a profit. And now when I decided to sell I plunged. Since we undoubtedly were entering upon a genuine bear market I was sure I should make the biggest killing of my career.

The market went off. Then it came back. It shaded off and then it began to advance steadily. My paper profits vanished and my paper losses grew. One day it looked as if not a bear would be left to tell the tale of the strictly genuine bear market. I couldn’t stand the gaff. I covered. It was just as well. If I hadn’t I wouldn’t have had enough left to buy a postal card. I lost most of my fur, but it was better to live to fight another day.

I had made a mistake. But where? I was bearish in a bear market. That was wise. I had sold stocks short. That was proper. I had sold them too soon. That was costly. My position was right but my play was wrong. However, every day brought the market nearer to the inevitable smash. So I waited and when the rally began to falter and pause I let them have as much stock as my sadly diminished margins permitted. I was right this time—for exactly one whole day, for on the next there was another rally. Another big bite out of yours truly! So I read the tape and covered and waited. In due course I sold again—and again they went down promisingly and then they rudely rallied.

8.3As gold specie flowed from London to San Francisco to settle fire insurance claims following the earthquake, a liquidity crisis began. The huge outflow of wealth tightened monetary conditions in England to such an extent that the Bank of England was forced to double its discount rate in an attempt to attract foreign gold. The situation was so dire that the Bank of France was forced to help by forwarding some £3 million worth of gold to “take some share in the international burden,” according to Hartley Withers, financial editor of the Times of London.

2

Eventually, the Bank of England retaliated by instituting a discriminatory policy against capital flows to the United States. This effectively cut off exports of gold, turned England from an exporter to an importer of capital, and pushed the American economy into recession. With gold no longer flowing from London, the New York financial markets were extremely vulnerable as interest rates were raised in an effort to restock depleted gold reserves.

The global economy was also booming. “Everything is in motion,” wrote Noyes; “railways, steamers, factories, harbors, docks; it is evident that so gigantic a development of trade and industry could not fail to have a marked influence upon the positions of the international money market.”

3 Surpassing what was seen in 1901, a flood of speculation further increased demand on bank deposits and gold reserves as stock traders went on margin to profit from rising prices.

This fever was by no means limited to the United States. The cessation of hostilities in Japan in the summer of 1905 was followed by what the government described as a “fever of enterprise” in which “prices of securities rose higher and higher.”

4 The German central bank raised its discount rate from 5% to 6% in late 1905, the highest level reached except during financial panics, in an attempt to curb the speculative mania. In Egypt between 1905 and 1907, stock and land speculation reached a point that the chairman of the Bank of Egypt described as meaning that the “people were apparently mad; I do not know what other word to use; they seemed to think that every company that came out was worth double its value before it had even started business.”

5The pressure on the banking system grew until on November 11, 1905, the reserves of New York banks fell below the 25% ratio to deposits required by the National Bank Act. As a result, the rates for demand loans on Wall Street increased to 25%, but stocks continued to rise. On December 28, the rate reached 125%. A few days later, Jacob Schiff told the New York Chamber of Commerce, “If the currency conditions of this country are not changed materially, I predict that you will have such a panic in this country as will make all previous panics look like child’s play.”

6It looked as if the market were doing its best to make me go back to my old and simple ways of bucket-shop trading. It was the first time I had worked with a definite forward-looking plan embracing the entire market instead of one or two stocks. I figured that I must win if I held out. Of course at that time I had not developed my system of placing my bets or I would have put out my short line on a declining market, as I explained to you the last time. I would not then have lost so much of my margin. I would have been wrong but not hurt. You see, I had observed certain facts but had not learned to co-ordinate them. My incomplete observation not only did not help but actually hindered.

I have always found it profitable to study my mistakes. Thus I eventually discovered that it was all very well not to lose your bear position in a bear market, but that at all times the tape should be read to determine the propitiousness of the time for operating. If you begin right you will not see your profitable position seriously menaced; and then you will find no trouble in sitting tight.

Of course to-day I have greater confidence in the accuracy of my observations—in which neither hopes nor hobbies play any part—and also I have greater facilities for verifying my facts as well as for variously testing the correctness of my views. But in 1906 the succession of rallies dangerously impaired my margins.

I was nearly twenty-seven years old. I had been at the game twelve years. But the first time I traded because of a crisis that was still to come I found that I had been using a telescope. Between my first glimpse of the storm cloud and the time for cashing in on the big break the stretch was evidently so much greater than I had thought that I began to wonder whether I really saw what I thought I saw so clearly. We had had many warnings and sensational ascensions in call-money rates. 8.3 Still some of the great financiers talked hopefully—at least to newspaper reporters—and the ensuing rallies in the stock market gave the lie to the calamity howlers. Was I fundamentally wrong in being bearish or merely temporarily wrong in having begun to sell short too soon?

I decided that I began too soon, but that I really couldn’t help it. Then the market began to sell off. That was my opportunity. I sold all I could, and then stocks rallied again, to quite a high level.

It cleaned me out.

There I was—right and busted!

I tell you it was remarkable. What happened was this: I looked ahead and saw a big pile of dollars. Out of it stuck a sign. It had “Help yourself,” on it, in huge letters. Beside it stood a cart with “Lawrence Livingston Trucking Corporation” painted on its side. I had a brand-new shovel in my hand. There was not another soul in sight, so I had no competition in the gold-shoveling, which is one beauty of seeing the dollar-heap ahead of others. The people who might have seen it if they had stopped to look were just then looking at baseball games instead, or motoring or buying houses to be paid for with the very dollars that I saw.

That was the first time that I had seen big money ahead, and I naturally started toward it on the run. Before I could reach the dollar-pile my wind went back on me and I fell to the ground. The pile of dollars was still there, but I had lost the shovel, and the wagon was gone. So much for sprinting too soon! I was too eager to prove to myself that I had seen real dollars and not a mirage. I saw, and knew that I saw. Thinking about the reward for my excellent sight kept me from considering the distance to the dollar-heap. I should have walked and not sprinted.

That is what happened. I didn’t wait to determine whether or not the time was right for plunging on the bear side. On the one occasion when I should have invoked the aid of my tape-reading I didn’t do it. That is how I came to learn that even when one is properly bearish at the very beginning of a bear market it is well not to begin selling in bulk until there is no danger of the engine back-firing.

8.4Baseball was the nation’s most popular professional sport in the 1890s and early 1900s. In 1906, the Chicago Cubs lost in the World Series to the Chicago White Sox. The Cubs were led by the famed infield combination of Joe Tinker, Johnny Evers, and Frank Chance; their best pitcher was “Three Finger” Mordecai Brown, who went 26-6 with a 1.04 earned run average. New York had two teams: the Highlanders in the American League, which would change its name to the Yankees seven years later, and the Giants in the National League. In 1907, the Chicago Cubs beat the Detroit Tigers in the World Series. Future Hall of Famer Ty Cobb led the Tigers’ attack, and in August that year, he got the first professional hit, a bunt single, off another future Hall of Famer, fire-balling pitcher Walter “Big Train” Johnson.

8.5 With monetary conditions tightening, James Hill wanted to lock up the capital needed to maintain and expand his rail network before it became unavailable. For illustration, look at the situation with the Northern Pacific. From 1898 to 1907, net earnings more than doubled, from $13 million to $33 million, as track mileage went from 4,350 to 5,444. Some $87 million in capital expenditures were made during this period. Wrote University of California at Berkeley business professor Stuart Daggett at the time:

Grades have been reduced, lines straightened, new branches built, real estate acquired, track re-laid and ballasted, bridges strengthened and renewed, equipment rebuilt and increased in amount, and other similar betterments undertaken. It is a work which all the great American systems have carried on.

7Due to the need to continue these efforts, shareholders voted to issue new common stock. The proceeds were aimed at improvements previously made out of cash flow.

8 Clearly, the directors were looking to hoard capital and protect dividend payments as the economic situation deteriorated.

The stock market situation warranted the change. In late 1905 to early 1906, there was a big boom in railroad stocks as years of fierce competition, reorganizations, and consolidations paved the way for increased profitability. In the fall of 1905, the Great Northern raised $25 million in equity capital and, corroborating Livermore’s account of events, “gave to its stockholders the privilege of subscribing to the new issue at par.”

9 Soon afterward, the Northern Pacific was bid up to $232.50 a share while the Great Northern zoomed to $348 compared to par values of $100.

8.6 To fully understand Livermore’s reaction to the share offering on what amounted to an installment plan, one must understand how new the concept was at that time. For instance, the modern automobile loan was not created until 1919 by General Motors. Until then, people would enroll in savings plans, socking away a few dollars a week until they had enough to purchase a car with cash.

10 Thus, a move to an installment payment plan was a clear sign of desperation.

In December 1906, the Great Northern offered $60 million in new stock at par, raising its capital to $210 million with payment extended over 16 months to April 1908. The Northern Pacific railway also offered $93 million in new stock at par, increasing its capital to $250 million with the last payment not required until January 1909.

11 An interest rate of 5% was charged on unpaid balances.

12Prices then broke badly, mainly because of tight money and the large new capital dilutions announced by Great

I had traded in a good many thousands of shares at Harding’s office in all those years, and, moreover, the firm had confidence in me and our relations were of the pleasantest. I think they felt that I was bound to be right again very shortly and they knew that with my habit of pushing my luck all I needed was a start and I’d more than recover what I had lost. They had made a great deal of money out of my trading and they would make more. So there was no trouble about my being able to trade there again as long as my credit stood high.

The succession of spankings I had received made me less aggressively cocksure; perhaps I should say less careless, for of course I knew I was just so much nearer to the smash. All I could do was wait watchfully, as I should have done before plunging. It wasn’t a case of locking the stable after the horse was stolen. I simply had to be sure, the next time I tried. If a man didn’t make mistakes he’d own the world in a month. But if he didn’t profit by his mistakes he wouldn’t own a blessed thing.

Well, sir, one fine morning I came downtown feeling cocksure once more. There wasn’t any doubt this time. I had read an advertisement in the financial pages of all the newspapers that was the high sign I hadn’t had the sense to wait for before plunging. It was the announcement of a new issue of stock by the Northern Pacific and Great Northern roads.

The payments were to be made on the installment plan for the convenience of the stockholders. This consideration was something new in Wall Street. It struck me as more than ominous.

For years the unfailing bull item on Great Northern preferred had been the announcement that another melon was to be cut, said melon consisting of the right of the lucky stockholders to subscribe at par to a new issue of Great Northern stock. These rights were valuable, since the market price was always way above par. But now the money market was such that the most powerful banking houses in the country were none too sure the stockholders would be able to pay cash for the bargain. And Great Northern preferred was selling at about 330!

As soon as I got to the office I told Ed Harding, “The time to sell is right now. This is when I should have begun. Just look at that ad, will you?”

He had seen it. I pointed out what the bankers’ confession amounted to in my opinion, but he couldn’t quite see the big break right on top of us. He thought it better to wait before putting out a very big short line by reason of the market’s habit of having big rallies. If I waited prices might be lower, but the operation would be safer.

“Ed,” I said to him, “the longer the delay in starting the sharper the break will be when it does start. That ad is a signed confession on the part of the bankers. What they fear is what I hope. This is a sign for us to get aboard the bear wagon. It is all we needed. If I had ten million dollars I’d stake every cent of it this minute.”

I had to do some more talking and arguing. He wasn’t content with the only inferences a sane man could draw from that amazing advertisement. It was enough for me, but not for most of the people in the office. I sold a little; too little.

A few days later St. Paul very kindly came out with an announcement of an issue of its own; either stock or notes, I forget which.

But that doesn’t matter. What mattered then was that I noticed the moment I read it that the date of payment was set ahead of the Great Northern and Northern Pacific payments, which had been announced earlier. It was as plain as though they had used a megaphone that grand old St. Paul was trying to beat the two other railroads to what little money there was floating around in Wall Street. The St. Paul’s bankers quite obviously feared that there wasn’t enough for all three and they were not saying, “After you, my dear Alphonse!” 8.9 If money already was that scarce—and you bet the bankers knew—what would it be later? The railroads needed it desperately. It wasn’t there. What was the answer?

Northern, Northern Pacific, and the Milwaukee & St. Paul railroads.

13 Prices also reversed at times and squeezed the short sellers—especially after the New York Central line increased its dividend by a quarter of a point—but the overall movement was down.

8.7 Preferred shares are a slightly different class of equity from common shares. Before dividends can be paid to common shareholders, preferred holders must receive a set dividend. After that, preferred holders are not entitled to additional disbursements of earnings. In this way, preferred stock has features of both debt and common equity.

In the case of Great Northern, the dividend on preferred shares was set at 7%, and James Hill “announced it as his opinion that 7% is a high enough dividend on any railroad stock,”

14 according to a newspaper report. To close the gap with other, higher-yielding railroad issues, Hill and a few other railroad men offered valuable subscription rights on new issuances of stock, which effectively boosted the dividend rate. In 1905, Great Northern preferred holders received rights valued at $33. Spread over a period of six years, this boosted the dividend yield to a whopping 12.5%.

8.8 The Milwaukee & St. Paul offered at par some $100 million to build its Pacific Coast extension through Montana, Idaho, and Washington from its hub on the shores of Lake Michigan. The last installment payment was not due till March 1909. Along with the offering from James Hill’s railroads, the Banker’s Magazine wrote in January: “It is not often that in one month so many large issues of securities are offered to the public or are announced as in contemplation as was the case last month.”

8.9 This phrase arose from a popular comic strip, Alphonse and Gaston, that first appeared in the New York Journal, a newspaper owned by William Randolph Hearst, in September 1901. The strip, by Frederick Burr Opper, followed a pair of klutzy Frenchmen depicted as overly polite. The lines “After you, my dear Alphonse!” and “No, you first, my dear Gaston!” entered into the language as catchphrases that have endured to describe a situation in which an individual is courteous to a fault.

8.10 The Great Northern preferred shares hit a high of $348 on February 9, 1906, before sliding to a low of $178 on December 26.

Sell ’em! Of course! The public, with their eyes fixed on the stock market, saw little—that week. The wise stock operators saw much—that year. That was the difference.

For me, that was the end of doubt and hesitation. I made up my mind for keeps then and there. That same morning I began what really was my first campaign along the lines that I have since followed. I told Harding what I thought and how I stood, and he made no objections to my selling Great Northern preferred at around 330, and other stocks at high prices.

I profited by my earlier and costly mistakes and sold more intelligently.

My reputation and my credit were reestablished in a jiffy. That is the beauty of being right in a broker’s office, whether by accident or not. But this time I was cold-bloodedly right, not because of a hunch or from skilful reading of the tape, but as the result of my analysis of conditions affecting the stock market in general. I wasn’t guessing. I was anticipating the inevitable. It did not call for any courage to sell stocks. I simply could not see anything but lower prices, and I had to act on it, didn’t I? What else could I do?

The whole list was soft as mush. Presently there was a rally and people came to me to warn me that the end of the decline had been reached. The big fellows, knowing the short interest to be enormous, had decided to squeeze the stuffing out of the bears, and so forth. It would set us pessimists back a few millions. It was a cinch that the big fellows would have no mercy. I used to thank these kindly counsellors. I wouldn’t even argue, because then they would have thought that I wasn’t grateful for the warnings.

The friend who had been in Atlantic City with me was in agony. He could understand the hunch that was followed by the earthquake. He couldn’t disbelieve in such agencies, since I had made a quarter of a million by intelligently obeying my blind impulse to sell Union Pacific. He even said it was Providence working in its mysterious way to make me sell stocks when he himself was bullish. And he could understand my second UP trade in Saratoga because he could understand any deal that involved one stock, on which the tip definitely fixed the movement in advance, either up or down. But this thing of predicting that all stocks were bound to go down used to exasperate him. What good did that kind of dope do anybody? How in blazes could a gentleman tell what to do?

I recalled old Partridge’s favourite remark—“Well, this is a bull market, you know”—as though that were tip enough for anybody who was wise enough; as in truth it was. It was very curious how, after suffering tremendous losses from a break of fifteen or twenty points, people who were still hanging on, welcomed a three-point rally and were certain the bottom had been reached and complete recovery begun.

One day my friend came to me and asked me, “Have you covered?”

“Why should I?” I said.

“For the best reason in the world.”

“What reason is that?”

“To make money. They’ve touched bottom and what goes down must come up. Isn’t that so?”

“Yes,” I answered. “First they sink to the bottom. Then they come up; but not right away. They’ve got to be good and dead a couple of days. It isn’t time for these corpses to rise to the surface. They are not quite dead yet.”

An old-timer heard me. He was one of those chaps that are always reminded of something. He said that William R. Travers, who was bearish, once met a friend who was bullish. They exchanged market views and the friend said, “Mr. Travers, how can you be bearish with the market so stiff?” and Travers retorted, “Yes! Th-the s-s-stiffness of d-death!” It was Travers who went to the office of a company and asked to be allowed to see the books. The clerk asked him, “Have you an interest in this company?” and Travers answered, “I sh-should s-say I had! I’m sh-short t-t-twenty thousand sh-shares of the stock!”

8.11 The Philadelphia & Reading Railroad operated throughout Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania and was brought out of bankruptcy by J. P. Morgan in the aftermath of the Panic of 1893. The float on Reading—or the shares available for trade—was relatively small because of the tight control insiders maintained.

15 In December 1906, when Livermore likely was operating in the stock, it fell from $152 to $129 in two weeks. These figures do not match up with those given, but the story behind them remains intact. At right is a Philadelphia & Reading train in 1897.

Well, the rallies grew feebler and feebler. I was pushing my luck for all I was worth. Every time I sold a few thousand shares of Great Northern preferred the price broke several points. I felt out weak spots elsewhere and let ’em have a few. All yielded, with one impressive exception; and that was Reading.

When everything else hit the toboggan slide Reading stood like the Rock of Gibraltar. Everybody said the stock was cornered. It certainly acted like it. They used to tell me it was plain suicide to sell Reading short. There were people in the office who were now as bearish on everything as I was. But when anybody hinted at selling Reading they shrieked for help. I myself had sold some short and was standing pat on it. At the same time I naturally preferred to seek and hit the soft spots instead of attacking the more strongly protected specialties. My tape reading found easier money for me in other stocks.

I heard a great deal about the Reading bull pool. It was a mighty strong pool. To begin with they had a lot of low-priced stock, so that their average was actually below the prevailing level, according to friends who told me. Moreover, the principal members of the pool had close connections of the friendliest character with the banks whose money they were using to carry their huge holdings of Reading. As long as the price stayed up the bankers’ friendship was staunch and steadfast. One pool member’s paper profit was upward of three millions. That allowed for some decline without causing fatalities. No wonder the stock stood up and defied the bears. Every now and then the room traders looked at the price, smacked their lips and proceeded to test it with a thousand shares or two. They could not dislodge a share, so they covered and went looking elsewhere for easier money. Whenever I looked at it I also sold a little more—just enough to convince myself that I was true to my new trading principles and wasn’t playing favourites.

In the old days the strength of Reading might have fooled me. The tape kept on saying, “Leave it alone!” But my reason told me differently. I was anticipating a general break, and there were not going to be any exceptions, pool or no pool.

I have always played a lone hand. I began that way in the bucket shops and have kept it up. It is the way my mind works. I have to do my own seeing and my own thinking. But I can tell you after the market began to go my way I felt for the first time in my life that I had allies—the strongest and truest in the world: underlying conditions. They were helping me with all their might. Perhaps they were a trifle slow at times in bringing up the reserves, but they were dependable, provided I did not get too impatient. I was not pitting my tape-reading knack or my hunches against chance. The inexorable logic of events was making money for me.

The thing was to be right; to know it and to act accordingly. General conditions, my true allies, said “Down!” and Reading disregarded the command. It was an insult to us. It began to annoy me to see Reading holding firmly, as though everything were serene. It ought to be the best short sale in the entire list because it had not gone down and the pool was carrying a lot of stock that it would not be able to carry when the money stringency grew more pronounced. Some day the bankers’ friends would fare no better than the friendless public. The stock must go with the others. If Reading didn’t decline, then my theory was wrong; I was wrong; facts were wrong; logic was wrong.

I figured that the price held because the Street was afraid to sell it. So one day I gave to two brokers each an order to sell four thousand shares, at the same time.

You ought to have seen that cornered stock, that it was sure suicide to go short of, take a headlong dive when those competitive orders struck it. I let ’em have a few thousand more. The price was 111 when I started selling it. Within a few minutes I took in my entire short line at 92.

I had a wonderful time after that, and in February of 1907 I cleaned up.

Great Northern pre ferred had gone down sixty or seventy points, and other stocks in proportion. I had made a good bit, but the reason I cleaned up was that I figured that the decline had discounted the immediate future. I looked for a fair recovery, but I wasn’t bullish enough to play for a turn. I wasn’t going to lose my position entirely. The market would not be right for me to trade in for a while. The first ten thousand dollars I made in the bucket shops I lost because I traded in and out of season, every day, whether or not conditions were right. I wasn’t making that mistake twice. Also, don’t forget that I had gone broke a little while before because I had seen this break too soon and started selling before it was time. Now when I had a big profit I wanted to cash in so that I could feel I had been right. The rallies had broken me before. I wasn’t going to let the next rally wipe me out. Instead of sitting tight I went to Florida. I love fishing and I needed a rest. I could get both down there. And besides, there are direct wires between Wall Street and Palm Beach.

8.12 Market weakness that started in December 1906 continued throughout 1907. The Great Northern preferred shares recovered slightly to $189.75 on January 2 before sliding all the way to $107.50 in October. The Financial Review wrote at the time: “The stock market was very much depressed during January, and there was a large and almost continuous decline in prices, with only fitful rallies except at the very close, when a somewhat more substantial recovery ensured. The disposition was to take a very unfavorable view of things.”

16Railroad stocks continued to recover somewhat into the early part of February. We can imagine that Livermore, having successfully timed the steep decline of December and January thanks to his new approach to the market, cautiously closed out his positions during this reactionary move to protect his profits, with the sting of recent failures in mind.

Although Livermore made a small fortune on his short positions in the rails, they would remain among the most popular and successful stocks for decades. And they were not just owned by the tycoons in the bull pool that Livermore fretted about. In 1908, the New York Times ran a magazine cover story titled “Two Million Partners Own the Corporations,” in which it complained about the “bitter warfare” that President Theodore Roosevelt was waging on large companies.

The Times said: “Who owns the corporations? The man in the street, whose financial education is gained from newspaper headlines and campaign cartoons, is forced to believe that a little coterie of Falstaffian gentlemen carry the ownership of the corporations around in their waistcoat pockets. But the hard, cold facts, as shown on the stock books of the great railroads and industrials of the country, show that there are 2,000,000 partners in American corporate enterprise, and that there are 20,000,000 persons whose savings are invested in these companies.”

17Illustrated with the table below, the article continues, “The misinformed speak of the Sugar Trust and the Havemeyers as though they were interchangeable names for the same thing, but no stock is more widely distributed than Sugar. The Havemeyers have 20,000 partners. Mr. Harriman has 30,000 partners in his Western railway empire, nearly 12,000 of whom have joined him since the Government opened fire on him.”

The article mounts the same defense for the Guggenheims before adding, with evident approval, that the public was defying the government’s anti-trust crusade by putting its money into stocks at a pace “as never before in history.”

17The next decade and a half would not be kind to investors who adhered to a buy-and-hold strategy. The month the article ran, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed at 83. Despite considerable volatility along the way, it would still be trading at the same level in 1922, 14 years later.

THE PUBLIC’S INTERESTS IN PROMINENT STOCKS.

ENDNOTES

1 Kerry A. Odell and Marc D. Weidenmier, “Real Shock, Monetary Aftershock: The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and the Panic of 1907,”

Journal of Economic History (September 2002): 1002-1027.

2 Charles Kindleberger,

Manias, Panics, and Crashes (1978), 189.

3 Alexander Dana Noyes,

Forty Years of American Finance (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909), 324.

7 Stuart Daggett,

Railroad Reorganization (1908), 309.

9 George Kennan,

E. H. Harriman (1922), 395.

11 “Retrospect,”

Financial Review (1907): 26.

12 “The Financial Situation,”

New York Times, December 17, 1906, 12.

14 “Subscription Rights as Extra Dividends,”

New York Times, August 27, 1906, 11.

15 “Topics in Wall Street,”

New York Times, November 4, 1905, 13.

16 “Retrospect.”

Financial Review. (1908) “Two Million Partners of Corporations.”

New York Times Magazine, SM1.

17 “Two Million Partners of Corporations.” Oct. 4, 1908.

New York Times Magazine, SM 1.

regularly for a long time. All traders do. But much of it was gos sip, some of it deliberately false, and the rest merely the personal opinion of the writers. The reputable weekly reviews when they touched upon underlying conditions were not entirely satisfactory to me. The point of view of the financial editors was not mine as a rule. It was not a vital matter for them to marshal their facts and draw their conclusions from them, but it was for me. Also there was a vast difference in our appraisal of the element of time. The analysis of the week that had passed was less important to me than the forecast of the weeks that were to come.

regularly for a long time. All traders do. But much of it was gos sip, some of it deliberately false, and the rest merely the personal opinion of the writers. The reputable weekly reviews when they touched upon underlying conditions were not entirely satisfactory to me. The point of view of the financial editors was not mine as a rule. It was not a vital matter for them to marshal their facts and draw their conclusions from them, but it was for me. Also there was a vast difference in our appraisal of the element of time. The analysis of the week that had passed was less important to me than the forecast of the weeks that were to come.

That was the first time that I had seen big money ahead, and I naturally started toward it on the run. Before I could reach the dollar-pile my wind went back on me and I fell to the ground. The pile of dollars was still there, but I had lost the shovel, and the wagon was gone. So much for sprinting too soon! I was too eager to prove to myself that I had seen real dollars and not a mirage. I saw, and knew that I saw. Thinking about the reward for my excellent sight kept me from considering the distance to the dollar-heap. I should have walked and not sprinted.

That was the first time that I had seen big money ahead, and I naturally started toward it on the run. Before I could reach the dollar-pile my wind went back on me and I fell to the ground. The pile of dollars was still there, but I had lost the shovel, and the wagon was gone. So much for sprinting too soon! I was too eager to prove to myself that I had seen real dollars and not a mirage. I saw, and knew that I saw. Thinking about the reward for my excellent sight kept me from considering the distance to the dollar-heap. I should have walked and not sprinted. The payments were to be made on the installment plan for the convenience of the stockholders. This consideration was something new in Wall Street. It struck me as more than ominous.

The payments were to be made on the installment plan for the convenience of the stockholders. This consideration was something new in Wall Street. It struck me as more than ominous.

But that doesn’t matter. What mattered then was that I noticed the moment I read it that the date of payment was set ahead of the Great Northern and Northern Pacific payments, which had been announced earlier. It was as plain as though they had used a megaphone that grand old St. Paul was trying to beat the two other railroads to what little money there was floating around in Wall Street. The St. Paul’s bankers quite obviously feared that there wasn’t enough for all three and they were not saying, “After you, my dear Alphonse!” 8.9 If money already was that scarce—and you bet the bankers knew—what would it be later? The railroads needed it desperately. It wasn’t there. What was the answer?

But that doesn’t matter. What mattered then was that I noticed the moment I read it that the date of payment was set ahead of the Great Northern and Northern Pacific payments, which had been announced earlier. It was as plain as though they had used a megaphone that grand old St. Paul was trying to beat the two other railroads to what little money there was floating around in Wall Street. The St. Paul’s bankers quite obviously feared that there wasn’t enough for all three and they were not saying, “After you, my dear Alphonse!” 8.9 If money already was that scarce—and you bet the bankers knew—what would it be later? The railroads needed it desperately. It wasn’t there. What was the answer? I profited by my earlier and costly mistakes and sold more intelligently.

I profited by my earlier and costly mistakes and sold more intelligently.

Great Northern pre ferred had gone down sixty or seventy points, and other stocks in proportion. I had made a good bit, but the reason I cleaned up was that I figured that the decline had discounted the immediate future. I looked for a fair recovery, but I wasn’t bullish enough to play for a turn. I wasn’t going to lose my position entirely. The market would not be right for me to trade in for a while. The first ten thousand dollars I made in the bucket shops I lost because I traded in and out of season, every day, whether or not conditions were right. I wasn’t making that mistake twice. Also, don’t forget that I had gone broke a little while before because I had seen this break too soon and started selling before it was time. Now when I had a big profit I wanted to cash in so that I could feel I had been right. The rallies had broken me before. I wasn’t going to let the next rally wipe me out. Instead of sitting tight I went to Florida. I love fishing and I needed a rest. I could get both down there. And besides, there are direct wires between Wall Street and Palm Beach.

Great Northern pre ferred had gone down sixty or seventy points, and other stocks in proportion. I had made a good bit, but the reason I cleaned up was that I figured that the decline had discounted the immediate future. I looked for a fair recovery, but I wasn’t bullish enough to play for a turn. I wasn’t going to lose my position entirely. The market would not be right for me to trade in for a while. The first ten thousand dollars I made in the bucket shops I lost because I traded in and out of season, every day, whether or not conditions were right. I wasn’t making that mistake twice. Also, don’t forget that I had gone broke a little while before because I had seen this break too soon and started selling before it was time. Now when I had a big profit I wanted to cash in so that I could feel I had been right. The rallies had broken me before. I wasn’t going to let the next rally wipe me out. Instead of sitting tight I went to Florida. I love fishing and I needed a rest. I could get both down there. And besides, there are direct wires between Wall Street and Palm Beach.