IX

I cruised off the coast of Florida. The fishing was good. I was out of stocks. My mind was easy. I was having a fine time. One day off Palm Beach some friends came alongside in a motor boat. One of them brought a newspaper with him. I hadn’t looked at one in some days and had not felt any desire to see one. I was not interested in any news it might print. But I glanced over the one my friend brought to the yacht, and I saw that the market had had a big rally; ten points and more.

I told my friends that I would go ashore with them. Moderate rallies from time to time were reasonable. But the bear market was not over; and here was Wall Street or the fool public or desperate bull interests disregarding monetary conditions

and marking up prices beyond reason or letting somebody else do it. It was too much for me. I simply had to take a look at the market. I didn’t know what I might or might not do. But I knew that my pressing need was the sight of the quotation board.

9.1 More than 14 years had passed since the last serious banking panic in 1893. The business community grew more confident after the return to the gold standard quelled the threat of inflation. A flurry of consolidation activity in major industries followed, which helped reduce competition and boost profitability. As a result, a speculative fever of rare magnitude dominated the public consciousness and redirected desperately needed funds from credit markets to the stock exchanges. The titans of banking and industry actively encouraged this in order to unload inside positions and cash out at the top.

But it was an unsustainable situation. Lefevre wrote of these conditions in a magazine article in 1908:

Aside from spasms of speculation in stocks and staples and metals, there has been unprecedented activity and expansion in industries and manufactures, not only in the United States but also in Germany and England and France. In our country, because of the national optimism, the expansion has been extraordinary, the volume of business simply colossal; our industries have grown at such a rate that we have been unable properly to finance that growth….We have had too much prosperity for the money; more than we could promptly pay for.

1This prosperity complicated the tight monetary conditions that prevailed in the wake of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the Boer War, and the war between Russia and Japan. All of these events increased the demand for gold just as its production was starting to wane worldwide. Interest rates rose as governments fought over what liquid capital remained.

2Add to this the advent of the trust company, which collected deposits and resembled a bank but undertook much more speculative investments and operated without regulatory oversights, and the financial system was left in a very vulnerable state. As a result, as Lefevre describes it:

[O]ne

cloudy day somebody asked for a dollar, and, not getting it promptly enough, very promptly squealed. That squeal was the signal for the chorus to join—the chorus of the entire world, which also wanted Money! Money! MONEY! It is sad to want money and not get it. But to ask for your own money and not get it is the civilized man’s hell.

39.2The beautiful resort town of Palm Beach, Florida, got its start after Standard Oil magnate Henry Morrison Flagler built two magnificent hotels in the area: the Royal Poinciana and the Breakers. Flagler also operated the Florida East Coast Railway, which served the town via an impressive overwater viaduct. Livermore’s broker, E. F. Hutton, also had interests in the area.

Hutton and his wife, Marjorie Post—heiress of the Post Cereals fortune—built their huge Mar-a-Lago estate on Palm Beach Island. The grounds were later transformed into the Mar-a-Lago Club, a private resort complex renovated and owned by Donald Trump, a real estate developer who would have been at home in the wheeler-dealer days of the early 1900s.

In Livermore’s time, the resorts were buzzing with the electricity and energy of the nation’s new prosperity. Business tycoons, financers, and royalty could be seen in hotel lobbies, on the white-sand beaches, and in the dining halls of Flagler’s impressive hotels.

My brokers, Harding Brothers, had a branch office in Palm Beach.

When I walked in I found there a lot of chaps I knew. Most of them were talking bullish. They were of the type that trade on the tape and want quick action. Such traders don’t care to look ahead very far because they don’t need to with their style of play. I told you how I’d got to be known in the New York office as the Boy Plunger. Of course people always magnify a fellow’s winnings and the size of the line he swings. The fellows in the office had heard that I had made a killing in New York on the bear side and they now expected that I again would plunge on the short side. They themselves thought the rally would go to a good deal further, but they rather considered it my duty to fight it.

I had come down to Florida on a fishing trip. I had been under a pretty severe strain and I needed my holiday. But the moment I saw how far the re covery in prices had gone I no longer felt the need of a vacation. I had not thought of just what I was going to do when I came ashore. But now I knew I must sell stocks. I was right, and I must prove it in my old and only way—by saying it with money. To sell the general list would be a proper, prudent, profitable and even patriotic action.

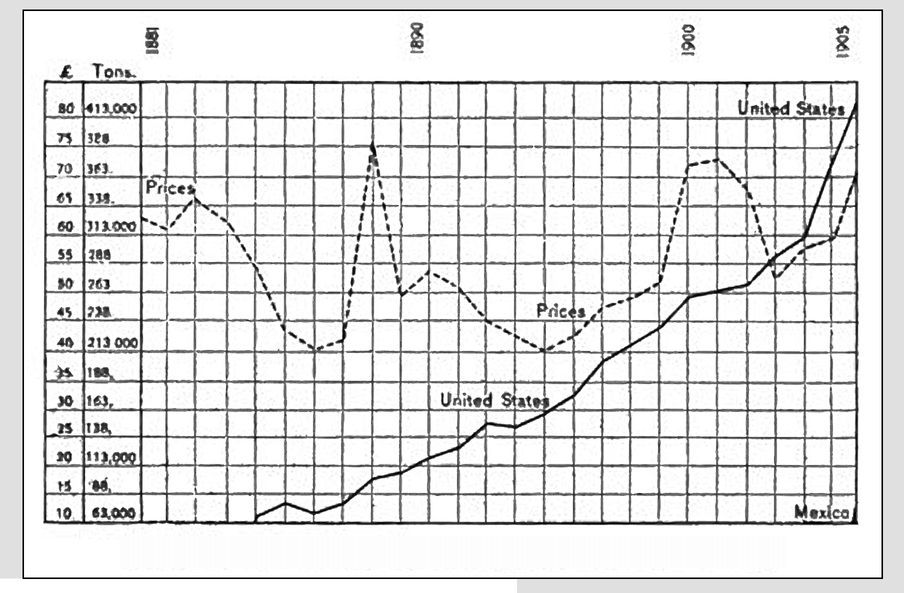

FIG. 5-—UNITED STATES COPPER OUTPUT FROM 1881 TO 1905

9.3 Copper plays an important role in the Panic of 1907, as an attempt to corner the stock of United Copper was the catalyst for numerous bank failures and a stock market crash.

The Anaconda Copper Mining Co. was founded by Marcus Daly in 1881 when he bought a small silver mine near Butte, Montana. After discovering a large deposit of copper, Daly sought outside investment to expand operations. First the Rothschild family got involved, purchasing stock in Anaconda. Then H. H. Rogers and William Rockefeller of Standard Oil formed the Amalgamated Copper Company in 1899 and purchased a majority share of Anaconda, thereby taking control of the company. From an initial stake of 75%, Amalgamated’s share of Anaconda dropped to less than 40% by 1904.

4 The two companies were traded separately on the New York Stock Exchange.

By 1887, Anaconda was the largest, most productive copper mine in the world.

5 Like now, the late 1800s and early 1900s were a time of great industrial progress. The red metal was in high demand since it was used in electrical wiring and plumbing—both of which were important in the construction of everything from passenger railcars and ocean liners to office buildings and residences. Therefore, copper stocks were closely followed by traders and very sensitive to the economic outlook.

The first thing I saw on the quotation board was that Anaconda

was on the point of crossing 300. It had been going up by leaps and bounds and there was apparently an aggressive bull party in it. It was an old trading theory of mine that when a stock crosses 100 or 200 or 300 for the first time the price does not stop at the even figure but goes a good deal higher, so that if you buy it as soon as it crosses the line it is almost certain to show you a profit. Timid people don’t like to buy a stock at a new high record. But I had the history of such movements to guide me.

9.4 The par or face value of a share is an archaic concept that has little relevance to modern stock traders. Originally used to set a minimum price during the initial public offer process, the par value would be printed on the stock certificate. Today, most stocks are “no-par” issues or have a par value set at an extremely low value.

The concept of par value, however, is still used in relation to bond prices to describe the amount that the issuer will pay to the bondholder at maturity. When a bond is issued, it is described as being sold at a discount if the price is below its face value. Conversely, a bond sold for more than its face value is said to be trading at a premium.

In Benjamin Graham’s classic Security Analysis, lowering the par value of the shares, as was the case with Anaconda, was described as being equivalent to a share split or a stock dividend. All of these actions would reduce the market value of the stock to better appeal to retail investors.

6Anaconda was only quarter stock—that is, the par of the shares was only twenty-five dollars. It took four hundred shares of it to equal the usual one hundred shares of other stocks, the par value of which was one hundred dollars. I figured that when it crossed 300 it ought to keep on going and probably touch 340 in a jiffy.

I was bearish, remember, but I was also a tape-reading trader. I knew Anaconda, if it went the way I figured, would move very quickly. Whatever moves fast always appeals to me. I have learned patience and how to sit tight, but my personal preference is for fleet movements, and Anaconda certainly was no sluggard. My buying it because it crossed 300 was prompted by the desire, always strong in me, of confirming my observations.

Just then the tape was saying that the buying was stronger than the selling, and therefore the general rally might easily go a bit further. It would be prudent to wait before going short. Still I might as well pay myself wages for waiting. This would be accomplished by taking a quick thirty points out of Anaconda. Bearish on the entire market and bullish on that one stock! So I bought thirty-two thousand shares of Anaconda—that is, eight thousand full shares. It was a nice little flyer but I was sure of my premises and I figured that the profit would help to swell the margin available for bear operations later on.

On the next day the telegraph wires were down on account of a storm up North or something of the sort. I was in Harding’s office waiting for news. The crowd was chewing the rag and wondering all sorts of things, as stock traders will when they can’t trade. Then we got a quotation—the only one that day: Anaconda, 292.

There was a chap with me, a broker I had met in New York. He knew I was long eight thousand full shares and I suspect that he had some of his own, for when we got that one quotation he certainly had a fit. He couldn’t tell whether the stock at that very moment had gone off another ten points or not. The way Anaconda had gone up it wouldn’t have been anything unusual for it to break twenty points. But I said to him, “Don’t you worry, John. It will be all right to-morrow.” That was really the way I felt. But he looked at me and shook his head. He knew better. He was that kind. So I laughed, and I waited in the office in case some quotation trickled through. But no, sir. That one was all we got: Anaconda, 292. It meant a paper loss to me of nearly one hundred thousand dollars. I had wanted quick action. Well, I was getting it.

The next day the wires were working and we got the quotations as usual. Anaconda opened at 298 and went up to 302¾, but pretty soon it began to fade away. Also, the rest of the market was not acting just right for a further rally. I made up my mind that if Anaconda went back to 301 I must consider the whole thing a fake movement. On a legitimate advance the price should have gone to 310 without stopping. If instead it reacted it meant that precedents had failed me and I was wrong; and the only thing to do when a man is wrong is to be right by ceasing to be wrong. I had bought eight thousand full shares in expectation of a thirty or forty point rise. It would not be my first mistake; nor my last.

Sure enough, Anaconda fell back to 301. The moment it touched that figure I sneaked over to the telegraph operator—they had a direct wire to the New York office—and I said to him, “Sell all my Anaconda, eight thousand full shares.” I said it in a low voice. I didn’t want anybody else to know what I was doing.

He looked up at me almost in horror. But I nodded and said, “All I’ve got!”

“Surely, Mr. Livingston, you don’t meant at the market?” and he looked as if he was going to lose a couple of millions of his own through bum execu tion by a careless broker. But I just told him, “Sell it! Don’t argue about it!”

9.5 Long-distance messages were transmitted in this era by Morse code, a rhythm-based communication system named for Samuel Morse, inventor of telegraphy. An intimate knowledge of Morse code would have allowed Ollie Black—a pseudonym, by the way, for a trader whose identity Livermore wished to hide—to translate Livermore’s order by sound alone.

Black’s eavesdropping technique would soon be obsolete. Manual tap entry was replaced by keyboard entry machines and automatic telegraphy equipment in the years after 1910. Telegram transmission reached a peak in 1919 when some 82 million messages were transmitted.

7 By 1969, it was down to eight million. In 2006, Western Union delivered its last telegram.

The two Black boys, Jim and Ollie, were in the office, out of hearing of the operator and myself. They were big traders who had come originally from Chicago, where they had been famous plungers in wheat, and were now heavy traders on the New York Stock Exchange. They were very wealthy and were high rollers for fair.

As I left the telegraph operator to go back to my seat in front of the quotation board Oliver Black nodded to me and smiled.

“You’ll be sorry, Larry,” he said.

I stopped and asked him, “What do you mean?”

“To-morrow you’ll be buying it back.”

“Buying what back?” I said. I hadn’t told a soul except the telegraph operator.

“Anaconda,” he said. “You’ll be paying 320 for it. That wasn’t a good move of yours, Larry.” And he smiled again.

“What wasn’t?” And I looked innocent.

“Selling your eight thousand Anaconda at the market; in fact, insisting on it,” said Ollie Black.

I knew that he was supposed to be very clever and always traded on inside news. But how he knew my business so accurately was beyond me. I was sure the office hadn’t given me away.

“Ollie, how did you know that?” I asked him.

He laughed and told me: “I got it from Charlie Kratzer.” That was the telegraph operator.

“But he never budged from his place,” I said.

“I couldn’t hear you and him whispering,” he chuckled. “But I heard every word of the message he sent to the New York office for you. I learned telegraphy years ago after I had a big row over a mistake in a message.

Since then when I do what you did just now—give an order by word of mouth to an operator—I want to be sure the operator sends the message as I give it to him. I know what he sends in my name. But you will be sorry you sold that Anaconda. It’s going to 500.”

“Not this trip, Ollie,” I said.

He stared at me and said, “You’re pretty cocky about it.”

“Not I; the tape,” I said. There wasn’t any ticker there so there wasn’t any tape. But he knew what I meant.

“I’ve heard of those birds,” he said, “who look at the tape and instead of seeing prices they see a railroad time-table of the arrival and departure of stocks. But they were in padded cells where they couldn’t hurt themselves.”

I didn’t answer him anything because about that time the boy brought me a memorandum. They had sold five thousand shares at 299¾. I knew our quotations were a little behind the market. The price on the board at Palm Beach when I gave the operator the order to sell was 301. I felt so certain that at that very moment the price at which the stock was actually selling on the Stock Exchange in New York was less, that if anybody had offered to take the stock off my hands at 296 I’d have been tickled to death to accept. What happened shows you that I am right in never trading at limits. Suppose I had limited my selling price to 300? I’d never have got it off. No, sir! When you want to get out, get out.

Now, my stock cost me about 300. They got off five hundred shares—full shares, of course—at 299¾. The next thousand they sold at 299 5/8. Then a hundred at ½; two hundred at 3/8 and two hundred at ¼. The last of my stock went at 298 ¾. It took Harding’s cleverest floor man fifteen minutes to get rid of that last one hundred shares. They didn’t want to crack it wide open.

The moment I got the report of the sale of the last of my long stock I started to do what I had really come ashore to do—that is, to sell stocks. I simply had to. There was the market after its outrageous rally, begging to be sold. Why, people were beginning to talk bullish again. The course of the market, however, told me that the rally had run its course. It was safe to sell them. It did not require reflection.

9.6As seen elsewhere in the book, Lefevre gives an account of stock prices that differs somewhat from the historical record. Anaconda’s shares reached a high of $300 on February 13, 1906, before falling to $223.50 in May and ending the year at $290.

8 The motivation for the big move was reports from Montana that “ore veins of incredible richness” had been discovered in the company’s mines.

9 As a result, Anaconda’s dividend was increased from 14% to 24%.

The New York Times reported that F. Augustus Heinze, who had sold his copper smelting interests in Montana to the Amalgamated Copper Co. for $10.5 million in early 1906, was largely responsible for Anaconda’s advance to $300.

10 No doubt this was done to maximize the purchase price of his assets. Heinze was likely behind the “aggressive bull party” that Livermore mentions.

9.7 In Chapter VIII, Livermore said: The market went off. Then it came back. It shaded off and then it began to advance steadily. My paper profits vanished and my paper losses grew.…I couldn’t stand the gaff. I covered.…If it hadn’t I wouldn’t have had enough left to buy a postal card. I lost most of my fur, but it was better to live to fight another day.

The next day Anaconda opened below 296 9.6 Oliver Black, who was waiting for a further rally, had come down early to be Johnny-on-the-spot when the stock crossed 320. I don’t know how much of it he was long of or whether he was long of it at all. But he didn’t laugh when he saw the opening prices, nor later in the day when the stock broke still more and the report came back to us in Palm Beach that there was no market for it at all.

Of course that was all the confirmation any man needed. My growing paper profit kept reminding me that I was right, hour by hour. Naturally I sold some more stocks. Everything! It was a bear market. They were all going down. The next day was Friday, Washington’s Birthday. I couldn’t stay in Florida and fish because I had put out a very fair short line, for me. I was needed in New York. Who needed me? I did! Palm Beach was too far, too remote. Too much valuable time was lost telegraphing back and forth.

I left Palm Beach for New York. On Monday I had to lie in St. Augustine three hours, waiting for a train. There was a broker’s office there, and naturally I had to see how the market was acting while I was waiting. Anaconda had broken several points since the last trading day. As a matter of fact, it didn’t stop going down until the big break that fall.

I got to New York and traded on the bear side for about four months. The market had frequent rallies as before, and I kept covering and putting them out again. I didn’t, strictly speaking, sit tight. Remember, I had lost every cent

of the three hundred thousand dollars I made out of the San Francisco earthquake break. I had been right, and nevertheless had gone broke. I was now playing safe—because after being down a man enjoys being up, even if he doesn’t quite make the top. The way to make money is to make it. The way to make big money is to be right at exactly the right time. In this business a man has to think of both theory and practice. A speculator must not be merely a student, he must be both a student and a speculator.

I did pretty well, even if I can now see where my campaign was tactically inadequate. When summer came the market got dull. It was a cinch that there would be nothing doing in a big way until well along in the fall. Everybody I knew had gone or was going to Europe. I thought that would be a good move for me. So I cleaned up. When I sailed for Europe I was a trifle more than three-quarters of a million to the good. To me that looked like some balance.

I was in Aix-les-Bains

enjoying myself. I had earned my vacation. It was good to be in a place like that with plenty of money and friends and acquaintances and everybody intent upon having a good time. Not much trouble about having that, in Aix. Wall Street was so far away that I never thought about it, and that is more than I could say of any resort in the United States. I didn’t have to listen to talk about the stock market. I didn’t need to trade. I had enough to last me quite a long time, and besides, when I got back I knew what to do to make much more than I could spend in Europe that summer.

One day I saw in the Paris Herald a dispatch from New York that Smelters had declared an extra dividend. They had run up the price of the stock and the entire market had come back quite strong. Of course that changed everything for me in Aix. The news simply meant that the bull cliques were still fighting desperately against conditions—against common sense and against common honesty, for they knew what was coming and were resorting to such schemes to put up the market in order to unload stocks before the storm struck them. It is possible they really did not believe the danger was as serious or as close at hand as I thought. The big men of the Street are as prone to be wishful thinkers as the politicians or the plain suckers. I myself can’t work that way. In a speculator such an attitude is fatal. Perhaps a manufacturer of securities or a promoter of new enterprises can afford to indulge in hope-jags.

9.8Located in southeastern France, Aix-les-Bains was a popular vacation destination for American financiers and businessmen, including J. P. Morgan. Morgan frequently “took the waters,” as they said at the time, and bathed in the area’s natural hot sulfur springs for his health. It was here, where Morgan was accompanied by “a Frenchwoman of title and quality,” that word of E. H. Harriman’s assault on the Northern Pacific reached the banker in 1901—forcing him to relocate to Paris.

11

9.9Livermore is likely referring to the Smelters Security Corp., which was formed in 1905 by Jacob Schiff of Kuhn, Loeb for the purpose of controlling the American Smelting & Refining Co.

12,

13 The latter was founded in 1899 by Standard Oil tycoons H. H. Rogers and William Rockefeller. In June, after reporting strong results for the end of its fiscal year, American Smelting increased its annual dividend from 7% to 8%.

14

9.10 After much delay, tight credit conditions finally began to be felt. The Bank of England increased its lending rate from 4% to 6% in October to stem the outflow of gold and warned London’s investment houses to curtail the extension of credit to the United States on threat of an increase in rates to 7%. According to historian Alexander Dana Noyes, in both March and August, there occurred stock sales “so enormous, and at such sacrifice of values, as to convince the experienced Wall Street man, despite official denials, that forced liquidation by the largest financiers was under way.”

15

Lefevre wrote of the slump and its aftermath in Everybody’s Magazine: “In Newport, Tuxedo, and Westchester County were heard voices ordering horses to be sold and stablemen to be dismissed; automobile repair-bills were angrily sent back for revision, and itemized accounts were insisted upon and extensions of time asked for.”

16The financial contagion was truly global. Markets in Egypt, then Japan, were thrown into turmoil. Brokerages in Germany succumbed to the pressure of 10% call money. Banks were forced to close in Chile. Holland and Denmark suffered a “formidable convulsion of their credit markets, with numerous banking failures.”

17 New York was next.

At all events, I knew that all bull manipulation was foredoomed to failure in that bear market. The instant I read the dispatch I knew there was only one thing to do to be comfortable, and that was to sell Smelters

short. Why, the insiders as much as begged me on their knees to do it, when they increased the dividend rate on the verge of a money panic. It was as infuriating as the old “dares” of your boyhood. They dared me to sell that particular stock short.

I cabled some selling orders in Smelters and advised my friends in New York to go short of it. When I got my report from the brokers I saw the price they got was six points below the quotations I had seen in the Paris Herald. It shows you what the situation was.

My plans had been to return to Paris at the end of the month and about three weeks later sail for New York, but as soon as I received the cabled reports from my brokers I went back to Paris. The same day I arrived I called at the steamship offices and found there was a fast boat leaving for New York the next day. I took it.

There I was, back in New York, almost a month ahead of my original plans, because it was the most comfortable place to be short of the market in. I had well over half a million in cash available for margins. My return was not due to my being bearish but to my being logical.

I sold more stocks. As money got tighter call-money rates went higher and prices of stocks lower.

I had foreseen it. At first, my foresight broke me. But now I was right and prospering. However, the real joy was in the consciousness that as a trader I was at last on the right track. I still had much to learn but I knew what to do. No more floundering, no more half-right methods. Tape reading was an important part of the game; so was beginning at the right time; so was sticking to your position. But my greatest discovery was that a man must study general conditions, to size them so as to be able to anticipate probabilities. In short, I had learned that I had to work for my money. I was no longer betting blindly or concerned with mastering the technic of the game, but with earning my successes by hard study and clear thinking. I also had found out that nobody was immune from the danger of making sucker plays. And for a sucker play a man gets sucker pay; for the paymaster is on the job and never loses the pay envelope that is coming to you.

Our office made a great deal of money. My own operations were so successful that they began to be talked about and, of course, were greatly exaggerated. I was credited with starting the breaks in various stocks. People I didn’t know by name used to come and congratulate me. They all thought the most wonderful thing was the money I had made. They did not say a word about the time when I first talked bearish to them and they thought I was a crazy bear with a stock-market loser’s vindictive grouch. That I had foreseen the money troubles was nothing. That my brokers’ bookkeeper had used a third of a drop of ink on the credit side of the ledger under my name was a marvellous achievement to them.

Friends used to tell me that in various offices the Boy Plunger in Harding Brothers’ office was quoted as making all sorts of threats against the bull cliques that had tried to mark up prices of various stocks long after it was plain that the market was bound to seek a much lower level. To this day they talk of my raids.

From the latter part of September on, the money market was megaphoning warnings to the entire world. But a belief in miracles kept people from selling what remained of their speculative holdings. Why, a broker told me a story the first week of October that made me feel almost ashamed of my moderation.

9.11 The Panic of 1907 began like so many other financial crises of this era: through an ill-fated exercise in unrestrained greed. At the center was Frederick Augustus Heinze. Born in Brooklyn and educated at Columbia University’s graduate school of business, he made a mess of the Standard Oil crowd and their attempt to gain a foothold in the Montana copper business at the tender age of 36. Heinze bought judges, corrupted politicians, and made himself a populist hero by paying higher wages than his competitors. His main avenue of attack was a provision of federal mining legislation called the apex law—which allowed him to claim that his veins of copper ran beneath Amalgamated Copper’s property.

After being paid millions to leave Montana, Heinze took his fortune to Wall Street, hooked up with “a little barrel-shaped man named Charles W. Morse” who built a monopoly in the ice business, and started buying small to midsize banks and trusts with the eventual goal of cornering copper stocks.

18 By controlling these institutions, Heinze and Morse could “command ready funds with which to play the market, and there wasn’t a finer gambling game in the world,” Lefevre wrote in a magazine article.

19Morse already controlled the Bank of North America. He used the bank’s funds to buy the Mercantile National Bank, which in turn allowed him to buy the Knickerbocker Trust Co. in a process dubbed “chain banking,” which involved the use of ownership shares as loan collateral.

20It was with these funds that Heinze and Morse started accumulating shares and options in the United Copper Co.—a firm Heinze had founded in 1902. Its Butte properties were sold to Amalgamated before Heinze used the company to acquire new mining assets in Nevada and British Columbia. No one really knew what was going on behind closed doors. As late as August, shareholders were worried about where Heinze was getting the money for United’s generous dividend payments.

21 The Standard Oil crowd was watching, waiting for Heinze to overstep so they could exact their revenge.

They got their chance on October 14, 1907, when United Copper went from $37.50 to $60 while all other important mining stocks declined. The next morning, the New York Times reported a “Skyrocket Jump” as the stock blasted higher in the first 15 minutes of trading.

22 Heinze had started his short squeeze believing he controlled enough of the shares to effectively corner it. He did not.

The next morning shares collapsed to $38 as other shareholders—who likely included H. H. Rogers and William Rockefeller—sold into the rise and supplied short sellers with the stock certificates they needed to repay their loans. Also contributing to the slide was a bungled execution of Heinze’s call options, negative stories about United

You remember that money loans used to be made on the floor of the Exchange around the Money Post. Those brokers who had received notice from their banks to pay call loans knew in a general way how much money they would have to borrow afresh. And of course the banks knew their position so far as loanable funds were concerned, and those which had money to loan would send it to the Exchange. This bank money was handled by a few brokers whose principal business was time loans. At about noon the renewal rate for the day was posted. Usually this represented a fair average of the loans made up to that time. Business was as a rule transacted openly by bids and offers, so that everyone knew what was going on. Between noon and about two o’clock there was ordinarily not much business done in money, but after delivery time—namely, 2:15 P.A.—brokers would know exactly what their cash position for the day would be, and they were able either to go to the Money Post and lend the balances that they had over or to borrow what they required. This business also was done openly.

Well, sometime early in October the broker I was telling you about came to me and told me that brokers were getting so they didn’t go to the Money Post when they had money to loan. The reason was that members of a couple of well-known commission houses were on watch there, ready to snap up any offerings of money. Of course no lender who offered money publicly could refuse to lend to these firms. They were solvent and the collateral was good enough. But the trouble was that once these firms borrowed money on call there was no prospect of the lender getting that money back. They simply said they couldn’t pay it back and the lender would willy-nilly have to renew the loan. So any Stock Exchange house that had money to loan to its fellows used to send its men about the floor instead of to the Post, and they would whisper to good friends, “Want a hundred?” meaning, “Do you wish to borrow a hundred thousand dollars?” The money brokers who acted for the banks presently adopted the same plan, and it was a dismal sight to watch the Money Post. Think of it!

Why, he also told me that it was a matter of Stock Exchange etiquette in those October days for the borrower to make his own rate of interest. You see, it fluctuated between 100 and 150 per cent per annum. I suppose by letting the borrower fix the rate the lender in some strange way didn’t feel so much like a usurer. But you bet he got as much as the rest. The lender naturally did not dream of not paying a high rate. He played fair and paid whatever the others did. What he needed was the money and was glad to get it.

Things got worse and worse. Finally there came the awful day of reckoning for the bulls and the optimists and the wishful thinkers and those vast hordes that, dreading the pain of a small loss at the beginning, were now about to suffer total amputation without anæsthetics. A day I shall never forget, October 24, 1907.

Reports from the money crowd early indicated that borrowers would have to pay whatever the lenders saw fit to ask. There wouldn’t be enough to go around. That day the money crowd was much larger than usual. When delivery time came that afternoon there must have been a hundred brokers around the Money Post, each hoping to borrow the money that his firm urgently needed. Without money they must sell what stocks they were carrying on margin—sell at any price they could get in a market where buyers were as scarce as money—and just then there was not a dollar in sight.

in newspapers controlled by the Rockefellers, and the calling of Heinze-Morse loans made by Rockefeller-influenced banks.

23 Heinze and Morse were forced to sell into the declining market to protect their banks’ cash reserves. By October 16, United was selling at $10 a share.

The scheme collapsed, pulling down the brokerage houses of Gross & Kleeburg and Otto Heinze & Company. Bank runs began on the three institutions whose managements and directors were involved with the corner attempt and who were forced to resign: Mercantile National Bank, New Amsterdam Bank, and the Bank of North America. The crisis burgeoned as depositor uncertainty spread. There was a run on the Knickerbocker Trust on Tuesday, October 22, after its president, Charles T. Barney, was found to be involved; other banks stopped clearing its checks. Knickerbocker failed the next day as a line of depositors formed outside the Trust Company of America.

By October 24, the panic reached its zenith. J. P. Morgan had been recalled from a church convention and was busily organizing a response. Old friends and rivals—including James R. Keene, E. H. Harriman, and the Rockefellers—were seen at Morgan’s opulent private library at 33 East 36th Street “as if they were visiting the Vatican,”

24 according to one account. Morgan decided that the line would be drawn at the Trust Company of America after his men examined its books and found it solvent: “Then, this is the place to stop the trouble,”

25 he said. By pooling the resources of the U.S. government as well as stronger financial institutions, Morgan was able to restore confidence in the banking system and end the crisis.

Heinze left Wall Street for the western frontier for a few years before he was sued in 1914 by Edwin Gould, son of Jay Gould, for $1.25 million in damages related to the sale of Mercantile National Bank stock. The jury awarded Gould the money, but he never collected. Heinze died, penniless, that November. Morse left town soon after the trial and was never heard from again. Charles Barney appealed to J. P. Morgan to save him from certain ruin but was rebuffed. Distraught, with his name tarnished, Barney died from a gunshot wound to the abdomen, an apparent suicide.

26,

27 9.12 Prior to 1869, borrowing and lending activity in support of the trading on the exchange floor was done from office to office. Messenger boys would scurry up and down the muddied streets carrying stock certificates to be pledged as collateral. Banks demanded the highest rate and were the last to be asked for loans. In those days, brokers would rather ask their peers for a loan on more favorable terms. The atmosphere was collegial among the members of the New York Stock Exchange.

As transaction volumes grew, the old way of doing business became unwieldy. The “Loan Crowd” was given its own room inside the NYSE. Eventually, starting in 1878, the cohort by then known as the Loan Market was given a post to mark its place on the trading fl oor. The original was made of wood. This was replaced by one made of iron in 1881 that was probably still in use in 1907. But throughout its history, the Money Post always carried the number 10.

28My friend’s partner was as bearish as I was. The firm therefore did not have to borrow, but my friend, the broker I told you about, fresh from seeing the haggard faces around the Money Post, came to me.

He knew I was heavily short of the entire market.

He said, “My God, Larry! I don’t know what’s going to happen. I never saw anything like it. It can’t go on. Something has got to give. It looks to me as if everybody is busted right now. You can’t sell stocks, and there is absolutely no money in there.”

“How do you mean?” I asked.

But what he answered was, “Did you ever hear of the classroom experiment of the mouse in a glass-bell when they begin to pump the air out of the bell? You can see the poor mouse breathe faster and faster, its sides heaving like overworked bellows, trying to get enough oxygen out of the decreasing supply in the bell. You watch it suffocate till its eyes almost pop out of their sockets, gasping, dying. Well, that is what I think of when I see the crowd at the Money Post! No money anywhere, and you can’t liquidate stocks because there is nobody to buy them. The whole Street is broke at this very moment, if you ask me!”

It made me think. I had seen a smash coming, but not, I admit, the worst panic in our history. It might not be profitable to anybody—if it went much further.

Finally it became plain that there was no use in waiting at the Post for money. There wasn’t going to be any. Then hell broke loose.

The president of the Stock Exchange, Mr. R. H. Thomas, so I heard later in the day, knowing that every house in the Street was headed for disaster, went out in search of succour. He called on James Stillman, president of the National City Bank, the richest bank in the United States. Its boast was that it never loaned money at a higher rate than 6 per cent.

Stillman heard what the president of the New York Stock Exchange had to say. Then he said, “Mr. Thomas, we’ll have to go and see Mr. Morgan about this.”

The two men, hoping to stave off the most disastrous panic in our financial history, went together to the office of J. P. Morgan & Co. and saw Mr. Morgan. Mr. Thomas laid the case before him. The moment he got through speaking Mr. Morgan said, “Go back to the Exchange and tell them that there will be money for them.”

“Where?”

“At the banks!”

So strong was the faith of all men in Mr. Morgan in those critical times that Thomas didn’t wait for further details but rushed back to the floor of the Exchange to announce the reprieve to his death-sentenced fellow members.

Then, before half past two in the afternoon, J. P. Morgan sent John T. Atterbury, of Van Emburgh & Atterbury, who was known to have close relations with J. P. Morgan & Co., into the money crowd. My friend said that the old broker walked quickly to the Money Post. He raised his hand like an exhorter at a revival meeting. The crowd, that at first had been calmed down somewhat by President Thomas’ announcement, was beginning to fear that the relief plans had miscarried and the worst was still to come. But when they looked at Mr. Atterbury’s face and saw him raise his hand they promptly petrified themselves.

In the dead silence that followed, Mr. Atterbury said, “I am authorized to lend ten million dollars. Take it easy! There will be enough for everybody!”

Then he began. Instead of giving to each borrower the name of the lender he simply jotted down the name of the borrower and the amount of the loan and told the borrower, “You will be told where your money is.” He meant the name of

9.13 Thomas originally suggested that the stock exchange be closed until a more moderate tone prevailed. J. P. Morgan would not have it, since he believed that would only further damage confidence in the financial system. Immediately following his conversation with Thomas, Morgan had a telephone message sent to the presidents of all the banks in the area. At two o’clock, they all gathered at his office. Morgan’s biographer, Herbert Satterlee, describes what happened next:

When they had gathered in his room he explained the situation, which was that the Stock Exchange houses needed in the aggregate at least $25,000,000, and unless that sum could be raised within the next quarter of an hour he feared that at lease fifty firms would go under. Mr. Stillman was the first to speak up and said that the National City Bank would furnish $5,000,000 to loan on the Exchange before closing time. Mr. Morgan called on each of the other men present to state how much his bank would lend, and in turn they said, “$500,000,” “$1,000,000,” or “One-half million”; and Perkins took down the figures. Some of them kept quiet, and Mr. Morgan had to speak to them pretty plainly before they announced their contributions to the fund. However, in not more than five minutes $27,000,000 was at Mr. Morgan’s command to loan to the Stock Exchange at 10 percent.”

29

the bank from which the borrower would get the money later.

I heard a day or two later that Mr. Morgan simply sent word to the frightened bankers of New York that they must provide the money the Stock Exchange needed.

“But we haven’t got any. We’re loaned up to the hilt,” the banks protested.

“You’ve got your reserves,” snapped J.P

“But we’re already below the legal limit,” they howled

“Use them! That’s what reserves are for!” And the banks obeyed and invaded the reserves to the extent of about twenty million dollars. It saved the stock market. The bank panic didn’t come until the following week. He was a man, J. P. Morgan was. They don’t come much bigger.

That was the day I remember most vividly of all the days of my life as a stock operator. It was the day when my winnings exceeded one million dollars. It marked the successful ending of my first deliberately planned trading campaign. What I had foreseen had come to pass. But more than all these things was this: a wild dream of mine had been realised. I had been king for a day!

I’ll explain, of course. After I had been in New York a couple of years I used to cudgel my brains trying to determine the exact reason why I couldn’t beat in a Stock Exchange house in New York the game that I had beaten as a kid of fifteen in a bucket shop in Boston. I knew that some day I would find out what was wrong and I would stop being wrong. I would then have not alone the will to be right but the knowledge to insure my being right. And that would mean power.

Please do not misunderstand me. It was not a deliberate dream of grandeur or a futile desire born of overweening vanity. It was rather a sort of feeling that the same old stock market that so baffled me in Fullerton’s office and in Harding’s would one day eat out of my hand. I just felt that such a day would come. And it did—October 24, 1907.

The reason why I say it is this: That morning a broker who had done a lot of business for my brokers and knew that I had been plunging on the bear side rode down in the company of one of the partners of the foremost banking house in the Street. My friend told the banker how heavily I had been trading, for I certainly pushed my luck to the limit. What is the use of being right unless you get all the good possible out of it?

Perhaps the broker exaggerated to make his story sound important. Perhaps I had more of a following than I knew. Perhaps the banker knew far better than I how critical the situation was. At all events, my friend said to me: “He listened with great interest to what I told him you said the market was going to do when the real selling began, after another push or two. When I got through he said he might have something for me to do later in the day.”

When the commission houses found out there was not a cent to be had at any price I knew the time had come. I sent brokers into the various crowds. Why, at one time there wasn’t a single bid for Union Pacific. Not at any price! Think of it! And in other stocks the same thing. No money to hold stocks and nobody to buy them.

I had enormous paper profits and the certainty that all that I had to do to smash prices still more was to send in orders to sell ten thousand shares each of Union Pacific and of a half dozen other good dividend-paying stocks and what would follow would be simply hell. It seemed to me that the panic that would be precipitated would be of such an intensity and character that the board of governors would deem it advisable to close the Exchange, as was done in August, 1914, when the World War broke out.

It would mean greatly increased profits on paper. It might also mean an inability to convert those profits into actual cash. But there were other things to consider, and one was that a further break would retard the recovery that I was beginning to figure on, the compensating improvement after all that blood-letting. Such a panic would do much harm to the country generally.

9.14 While Livermore was enjoying himself, rightfully proud of his accomplishments, it was a time of extreme duress for the rest of Wall Street and for the average man. Perhaps empathy, and not just cold-blooded calculation, played into his decision to turn and go long as the panic deepened. In this photo we see a common sight during the panic: Depositors lined up outside the Nineteenth Ward Bank in New York, hoping to secure a share of their savings.

I made up my mind that since it was unwise and unpleasant to continue actively bearish it was illogical for me to stay short. So I turned and began to buy. 9.14

It wasn’t long after my brokers began to buy in for me—and, by the way, I got bottom prices—that the banker sent for my friend.

“I have sent for you,” he said, “because I want you to go instantly to your friend Livingston and say to him that we hope he will not sell any more stocks to-day. The market can’t stand much more pressure. As it is, it will be an immensely difficult task to avert a devastating panic. Appeal to your friend’s patriotism. This is a case where a man has to work for the benefit of all. Let me know at once what he says.”

My friend came right over and told me. He was very tactful. I suppose he thought that having planned to smash the market I would consider his request as equivalent to throwing away the chance to make about ten million dollars. He knew I was sore on some of the big guns for the way they had acted trying to land the public with a lot of stock when they knew as well as I did what was coming.

As a matter of fact, the big men were big sufferers and lots of the stocks I bought at the very bottom were in famous financial names. I didn’t know it at the time, but it did not matter. I had practically covered all my shorts and it seemed to me there was a chance to buy stocks cheap and help the needed recovery in prices at the same time—if nobody hammered the market.

So I told my friend, “Go back and tell Mr. Blank that I agree with them and that I fully realised the gravity of the situation even before he sent for you. I not only will not sell any more stocks to-day, but I am going in and buy as much as I can carry.” And I kept my word. I bought one hundred thousand shares that day, for the long account. I did not sell another stock short for nine months.

That is why I said to friends that my dream had come true and that I had been king for a moment. The stock market at one time that day certainly was at the mercy of anybody who wanted to hammer it. I do not suffer from delusions of grandeur; in fact you know how I feel about being accused of raiding the market and about the way my operations are exaggerated by the gossip of the Street.

I came out of it in fine shape. The newspapers said that Larry Livingston, the Boy Plunger, had made several millions. Well, I was worth over one million after the close of business that day. But my biggest winnings were not in dollars but in the intangibles: I had learned what a man must do in order to make big money; I was permanently out of the gambler class; I had at last learned to trade intelligently in a big way. It was a day of days for me.

ENDNOTES

1 Edwin Lefevre, “The Game Got Them,”

Everybody’s Magazine (January 1908): 7-8.

2 Robert Sobel,

Panic on Wall Street (1968), 301.

3 Lefevre, “Game Got Them,” 9.

4 John Moody, “The Truth About the Trusts,” 1904. 3.

5 Horace J. Stevens and Walter Harvey Weed,

The Copper Handbook (1911), 19.

6 Benjamin Graham, and David Le Fevre Dodd. “

Security Analysis.” 441. 1934.

7 Beauchamp, K.G. “History of Telegraphy,” 2001, 399.

8 “Retrospect,”

Financial Review (1907): 12.

9 “Topics in Wall Street.”

New York Times, October 17, 1906, 13.

11 Matthew Josephson,

The Robber Barons (1934), 436.

12 Debi Unger,

The Guggenheims (2005), 80.

13 “Some Smelted Finance,”

New York Times, May 14, 1905, 15.

14 “Smelting & Refining Co.’s Earnings Show Large Gain,”

Wall Street Journal, June 7, 1907, 5.

15 Alexander Dana Noyes,

Forty Years of American Finance (1909), 358.

16 Lefevre, “The Game Got Them,” 9.

18 Frederick Lewis Allen,

The Lords of Creation (1935), 115-116.

20 Noyes,

Forty Years of American Finance, 365.

21 “Light on Heinze Mining Schemes,”

New York Times, August 1, 1907, 11.

22 “Skyrocket Jump in United Copper,”

New York Times, October 15, 1907, 11.

23 Sobel,

Panic on Wall Street, 308.

24 Robert Sobel,

The Big Board (1965), 193.

26 Sobel,

Panic on Wall Street, 321.

27 Robert F. Bruner and Sean D. Carr,

The Panic of 1907 (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), ix-xiii.

28 Stedman, Edmund Clarence. “The New York Stock Exchange,” 1905, 448.

29 Satterlee, Herbert L. “J. Pierpont Morgan,” 1940, 468-472.

and marking up prices beyond reason or letting somebody else do it. It was too much for me. I simply had to take a look at the market. I didn’t know what I might or might not do. But I knew that my pressing need was the sight of the quotation board.

and marking up prices beyond reason or letting somebody else do it. It was too much for me. I simply had to take a look at the market. I didn’t know what I might or might not do. But I knew that my pressing need was the sight of the quotation board. and marking up prices beyond reason or letting somebody else do it. It was too much for me. I simply had to take a look at the market. I didn’t know what I might or might not do. But I knew that my pressing need was the sight of the quotation board.

and marking up prices beyond reason or letting somebody else do it. It was too much for me. I simply had to take a look at the market. I didn’t know what I might or might not do. But I knew that my pressing need was the sight of the quotation board.

When I walked in I found there a lot of chaps I knew. Most of them were talking bullish. They were of the type that trade on the tape and want quick action. Such traders don’t care to look ahead very far because they don’t need to with their style of play. I told you how I’d got to be known in the New York office as the Boy Plunger. Of course people always magnify a fellow’s winnings and the size of the line he swings. The fellows in the office had heard that I had made a killing in New York on the bear side and they now expected that I again would plunge on the short side. They themselves thought the rally would go to a good deal further, but they rather considered it my duty to fight it.

When I walked in I found there a lot of chaps I knew. Most of them were talking bullish. They were of the type that trade on the tape and want quick action. Such traders don’t care to look ahead very far because they don’t need to with their style of play. I told you how I’d got to be known in the New York office as the Boy Plunger. Of course people always magnify a fellow’s winnings and the size of the line he swings. The fellows in the office had heard that I had made a killing in New York on the bear side and they now expected that I again would plunge on the short side. They themselves thought the rally would go to a good deal further, but they rather considered it my duty to fight it.

was on the point of crossing 300. It had been going up by leaps and bounds and there was apparently an aggressive bull party in it. It was an old trading theory of mine that when a stock crosses 100 or 200 or 300 for the first time the price does not stop at the even figure but goes a good deal higher, so that if you buy it as soon as it crosses the line it is almost certain to show you a profit. Timid people don’t like to buy a stock at a new high record. But I had the history of such movements to guide me.

was on the point of crossing 300. It had been going up by leaps and bounds and there was apparently an aggressive bull party in it. It was an old trading theory of mine that when a stock crosses 100 or 200 or 300 for the first time the price does not stop at the even figure but goes a good deal higher, so that if you buy it as soon as it crosses the line it is almost certain to show you a profit. Timid people don’t like to buy a stock at a new high record. But I had the history of such movements to guide me. Since then when I do what you did just now—give an order by word of mouth to an operator—I want to be sure the operator sends the message as I give it to him. I know what he sends in my name. But you will be sorry you sold that Anaconda. It’s going to 500.”

Since then when I do what you did just now—give an order by word of mouth to an operator—I want to be sure the operator sends the message as I give it to him. I know what he sends in my name. But you will be sorry you sold that Anaconda. It’s going to 500.” of the three hundred thousand dollars I made out of the San Francisco earthquake break. I had been right, and nevertheless had gone broke. I was now playing safe—because after being down a man enjoys being up, even if he doesn’t quite make the top. The way to make money is to make it. The way to make big money is to be right at exactly the right time. In this business a man has to think of both theory and practice. A speculator must not be merely a student, he must be both a student and a speculator.

of the three hundred thousand dollars I made out of the San Francisco earthquake break. I had been right, and nevertheless had gone broke. I was now playing safe—because after being down a man enjoys being up, even if he doesn’t quite make the top. The way to make money is to make it. The way to make big money is to be right at exactly the right time. In this business a man has to think of both theory and practice. A speculator must not be merely a student, he must be both a student and a speculator. enjoying myself. I had earned my vacation. It was good to be in a place like that with plenty of money and friends and acquaintances and everybody intent upon having a good time. Not much trouble about having that, in Aix. Wall Street was so far away that I never thought about it, and that is more than I could say of any resort in the United States. I didn’t have to listen to talk about the stock market. I didn’t need to trade. I had enough to last me quite a long time, and besides, when I got back I knew what to do to make much more than I could spend in Europe that summer.

enjoying myself. I had earned my vacation. It was good to be in a place like that with plenty of money and friends and acquaintances and everybody intent upon having a good time. Not much trouble about having that, in Aix. Wall Street was so far away that I never thought about it, and that is more than I could say of any resort in the United States. I didn’t have to listen to talk about the stock market. I didn’t need to trade. I had enough to last me quite a long time, and besides, when I got back I knew what to do to make much more than I could spend in Europe that summer. short. Why, the insiders as much as begged me on their knees to do it, when they increased the dividend rate on the verge of a money panic. It was as infuriating as the old “dares” of your boyhood. They dared me to sell that particular stock short.

short. Why, the insiders as much as begged me on their knees to do it, when they increased the dividend rate on the verge of a money panic. It was as infuriating as the old “dares” of your boyhood. They dared me to sell that particular stock short. I had foreseen it. At first, my foresight broke me. But now I was right and prospering. However, the real joy was in the consciousness that as a trader I was at last on the right track. I still had much to learn but I knew what to do. No more floundering, no more half-right methods. Tape reading was an important part of the game; so was beginning at the right time; so was sticking to your position. But my greatest discovery was that a man must study general conditions, to size them so as to be able to anticipate probabilities. In short, I had learned that I had to work for my money. I was no longer betting blindly or concerned with mastering the technic of the game, but with earning my successes by hard study and clear thinking. I also had found out that nobody was immune from the danger of making sucker plays. And for a sucker play a man gets sucker pay; for the paymaster is on the job and never loses the pay envelope that is coming to you.

I had foreseen it. At first, my foresight broke me. But now I was right and prospering. However, the real joy was in the consciousness that as a trader I was at last on the right track. I still had much to learn but I knew what to do. No more floundering, no more half-right methods. Tape reading was an important part of the game; so was beginning at the right time; so was sticking to your position. But my greatest discovery was that a man must study general conditions, to size them so as to be able to anticipate probabilities. In short, I had learned that I had to work for my money. I was no longer betting blindly or concerned with mastering the technic of the game, but with earning my successes by hard study and clear thinking. I also had found out that nobody was immune from the danger of making sucker plays. And for a sucker play a man gets sucker pay; for the paymaster is on the job and never loses the pay envelope that is coming to you.

He knew I was heavily short of the entire market.

He knew I was heavily short of the entire market.