X

The recognition of our own mistakes should not benefit us any more than the study of our successes. But there is a natural tendency in all men to avoid punishment. When you associate certain mistakes with a licking, you do not hanker for a second dose, and, of course, all stock-market mistakes wound you in two tender spots—your pocketbook and your vanity. But I will tell you something curious: A stock speculator sometimes makes mistakes and knows that he is making them. And after he makes them he will ask himself why he made them; and after thinking over it cold-bloodedly a long time after the pain of punishment is over he may learn how he came to make them, and when, and at what particular point of his trade; but not why. And then he simply calls himself names and lets it go at that.

Of course, if a man is both wise and lucky, he will not make the same mistake twice. But he will make any one of the ten thousand brothers or cousins of the original. The Mistake family is so large that there is always one of them around when you want to see what you can do in the fool-play line.

To tell you about the first of my million-dollar mistakes I shall have to go back to this time when I first became a millionaire, right after the big break of October, 1907. As far as my trading went, having a million merely meant more reserves. Money does not give a trader more comfort, because, rich or poor, he can make mistakes and it is never comfortable to be wrong. And when a millionaire is right his money is merely one of his several servants. Losing money is the least of my troubles. A loss never bothers me after I take it. 10.1 I forget it overnight. But being wrong—not taking the loss—that is what does the damage to the pocketbook and to the soul. You remember Dickson G. Watts’ story about the man who was so nervous that a friend asked him what was the matter. 10.2

10.1This is another key tenet of Livermore’s style of trading, which he repeats several times in the book and has become a central theme of modern trading as well: Take losses quickly, and let your winners run.

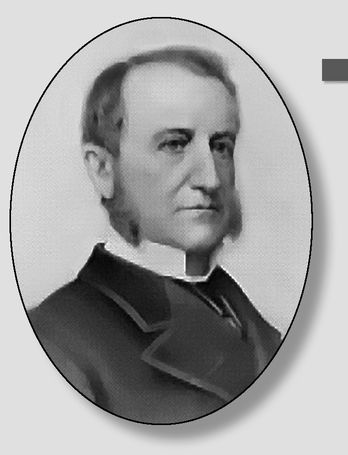

10.2Kentucky native Dickson G. Watts moved to New York at age 35. He joined the New York Cotton Exchange in 1870 and was twice elected president, with his last stint from 1878 to 1880.

1 He was a well-regarded trader of the era, and in fact, Livermore states that Watts “wrote the book on speculating,” and quotes him repeatedly.

Watts’s famed book, Speculation as a Fine Art and Thoughts on Life, is really a small pamphlet of epigrams, and only the first 15 pages focus on the markets. The story relayed here about a cotton trader who cannot sleep because he is worried about a large position is an embellished version of Watts’s fourth “absolute” law. Watts argues that “when the mind is not satisfied with the position taken, or the interest is too large for safety,” a trader should “sell down to a sleeping point.”

2Watts’s other laws show up elsewhere in Reminiscences. Watts argues that, contrary to popular opinion, “It is better to ‘average up’ than to ‘average down,’ “ and explains why with a math exercise. He later argues that one should “never completely and at once reverse a position” from long to short, or vice versa, because it can be psychologically “very hazardous.” The reason: Should the market reverse and go back to its original direction, “complete demoralization ensues.” Instead, he says, change in the original position should be made “cautiously, thus keeping the judgment clear and preserving the balance of mind.”

Elsewhere in his book, Watts declares that traders should not get too hung up on economic numbers because they obscure a comprehensive view of a market situation. He states: “Those who confine themselves too closely to statistics are poor guides” and then quotes British statesman George Canning’s comment: “There is nothing so fallacious as facts, except figures.”

Here are two more Watts’s epigrams that show up in Livermore’s words in Reminiscences: “When in doubt, do nothing. Don’t enter the market on half-convictions.” And: “A man must think for himself and follow his own convictions. A man cannot have another man’s ideas any more than he can another man’s soul or another man’s body.”

3“I can’t sleep,” answered the nervous one.

“Why not?” asked the friend.

“I am carrying so much cotton that I can’t sleep thinking about it. It is wearing me out. What can I do?”

“Sell down to the sleeping point,” answered the friend.

As a rule a man adapts himself to conditions so quickly that he loses the perspective. He does not feel the difference much—that is, he does not vividly remember how it felt not to be a millionaire. He only remembers that there were things he could not do that he can do now. It does not take a reasonably young and normal man very long to lose the habit of being poor. It requires a little longer to forget that he used to be rich. I suppose that is because money creates needs or encourages their multiplication. I mean that after a man makes money in the stock market he very quickly loses the habit of not spending. But after he loses his money it takes him a long time to lose the habit of spending.

After I took in my shorts and went long in October, 1907, I decided to take it easy for a while. I bought a yacht and planned to go off on a cruise in Southern waters.

I am crazy about fishing and I was due to have the time of my life. I looked forward to it and expected to go any day. But I did not. The market wouldn’t let me.

I always have traded in commodities as well as in stocks. I began as a youngster in the bucket shops. I studied those markets for years, though perhaps not so assiduously as the stock market. As a matter of fact, I would rather play commodities than stocks.

There is no question about their greater legitimacy, as it were. It partakes more of the nature of a commercial venture than trading in stocks does. A man can approach it as he might any mercantile problem. It may be possible to use fictitious arguments for or against a certain trend in a commodity market; but success will be only temporary, for in the end the facts are bound to prevail, so that a trader gets dividends on study and observation, as he does in a regular business. He can watch and weigh conditions and he knows as much about it as anyone else. He need not guard against inside cliques. Dividends are not unexpectedly passed or increased overnight in the cotton market or in wheat or corn. In the long run commodity prices are governed but by one law—the economic law of demand and supply. The business of the trader in commodities is simply to get facts about the demand and the supply, present and prospective. He does not indulge in guesses about a dozen things as he does in stocks. It always appealed to me—trading in commodities.

Of course the same things happen in all speculative markets. The message of the tape is the same. That will be perfectly plain to anyone who will take the trouble to think. He will find if he asks himself questions and considers conditions, that the answers will supply themselves directly. But people never take the trouble to ask questions, leave alone seeking answers. The average American is from Missouri everywhere and at all times except when he goes to the brokers’ offices and looks at the tape, whether it is stocks or commodities. The one game of all games that really requires study before making a play is the one he goes into without his usual highly intelligent preliminary and precautionary doubts. He will risk half his fortune in the stock market with less reflection than he devotes to the selection of a medium-priced automobile.

This matter of tape reading is not so complicated as it appears. Of course you need experience. But it is even more important to keep certain funda mentals in mind. To read the tape is not to have your fortune told. The tape does not tell you how much you will surely be worth next Thursday at 1:35 P.M. The object of reading the tape is to ascertain, first, how and, next, when to trade—that is, whether it is wiser to buy than to sell. It works exactly the same for stocks as for cotton or wheat or corn or oats.

10.3The period from 1880 to 1905 is considered to be the golden age of yachting, and all the market luminaries of the time, including the Astors, Vanderbilts, Morgans, Jay Gould, and William Randolph Hearst, tried to outdo each other by spending lavish sums on sail- and steam-powered boats with palatial interiors. Gould’s biggest, the Atlanta, was 233 feet long and run by a crew of 52. William K. Vanderbilt had a 291-foot steamer called Valiant that had 20 staterooms for friends and family.

4

The purchase of smaller yachts was well within the means of successful traders, who used them to go fishing out of marinas in Fort Myers, Miami, and Palm Beach.

10.4Livermore prefers commodities because prices were less prone to manipulation. In arguing that commodities respond mainly to the laws of supply and demand, he further reveals his exasperation with what he calls “inside cliques.”

10.5In this chapter, Livermore provides the most extended explanation of his trading philosophy. It is one that any technical trader today would recognize: “Prices ... move along the line of least resistance.” He energetically explains that speculators should not worry whether a stock looks too cheap or too dear but only if it is more likely to go up or down.

Livermore further observes that stocks should be bought on breakouts and shorted on breakdowns; stocks are never too high to buy or too low to sell; a speculator must keep an open mind on fundamentals and focus primarily on price action; trends appear before news is published; bearish news is ignored in bull cycles, and vice versa; losing trades should never be added to, because “there is no profit in being wrong”; and a speculator’s chief enemies are always the natural impulses of his own human nature. Echoing the words of Dickson Watts in laying down his “laws,” Livermore adds that his views on trading are “incontrovertible statements” regardless of what anybody says to the contrary.

You watch the market—that is, the course of prices as recorded by the tape—with one object: to determine the direction—that is, the price tendency. Prices, we know, will move either up or down according to the resistance they encounter. For purposes of easy explanation we will say that prices, like everything else, move along the line of least reistance.

They will do whatever comes easiest, therefore they will go up if there is less resistance to an advance than to a decline; and vice versa.

Nobody should be puzzled as to whether a market is a bull or a bear market after it fairly starts. The trend is evident to a man who has an open mind and reasonably clear sight, for it is never wise for a speculator to fit his facts to his theories. Such a man will, or ought to, know whether it is a bull or a bear market, and if he knows that he knows whether to buy or to sell. It is therefore at the very inception of the movement that a man needs to know whether to buy or to sell.

Let us say, for example, that the market, as it usually does in those between-swings times, fluctuates within a range of ten points; up to 130 and down to 120. It may look very weak at the bottom; or, on the way up, after a rise of eight or ten points, it may look as strong as anything. A man ought not to be led into trading by tokens. He should wait until the tape tells him that the time is ripe. As a matter of fact, millions upon millions of dollars have been lost by men who bought stocks because they looked cheap or sold them because they looked dear. The speculator is not an investor. His object is not to secure a steady return on his money at a good rate of interest, but to profit by either a rise or a fall in the price of whatever he may be speculating in. Therefore the thing to determine is the speculative line of least resistance at the moment of trading; and what he should wait for is the moment when that line defines itself, because that is his signal to get busy.

Reading the tape merely enables him to see that at 130 the selling had been stronger than the buying and a reaction in the price logically followed. Up to the point where the selling prevailed over the buying, superficial students of the tape may conclude that the price is not going to stop short of 150, and they buy. But after the reaction begins they hold on, or sell out at a small loss, or they go short and talk bearish. But at 120 there is stronger resistance to the decline. The buying prevails over the selling, there is a rally and the shorts cover. The public is so often whipsawed that one marvels at their persistence in not learning their lesson.

Eventually something happens that increases the power of either the upward or the downward force and the point of greatest resistance moves up or down—that is, the buying at 130 will for the first time be stronger than the selling, or the selling at 120 be stronger than the buying. The price will break through the old barrier or movement-limit and go on. As a rule, there is always a crowd of traders who are short at 120 because it looked so weak, or long at 130 because it looked so strong, and, when the market goes against them they are forced, after a while, either to change their minds and turn or to close out. In either event they help to define even more clearly the price line of least resistance. Thus the intelligent trader who has patiently waited to determine this line will enlist the aid of fundamental trade conditions and also of the force of the trading of that part of the community that happened to guess wrong and must now rectify mistakes. Such corrections tend to push prices along the line of least resistance.

And right here I will say that, though I do not give it as a mathematical certainty or as an axiom of speculation, my experience has been that accidents—that is, the unexpected or unforeseen—have always helped me in my market position whenever the latter has been based upon my determination of the line of least resistance. Do you remember that Union Pacific episode at Saratoga that I told you about? Well, I was long because I found out that the line of least resistance was upward. I should have stayed long instead of letting my broker tell me that insiders were selling stocks. It didn’t make any difference what was going on in the directors’ minds. That was something I couldn’t possibly know. But I could and did know that the tape said: “Going up!” And then came the unexpected raising of the dividend rate and the thirty-point rise in the stock. At 164 prices looked mighty high, but as I told you before, stocks are never too high to buy or too low to sell. The price, per se, has nothing to do with establishing my line of least resistance.

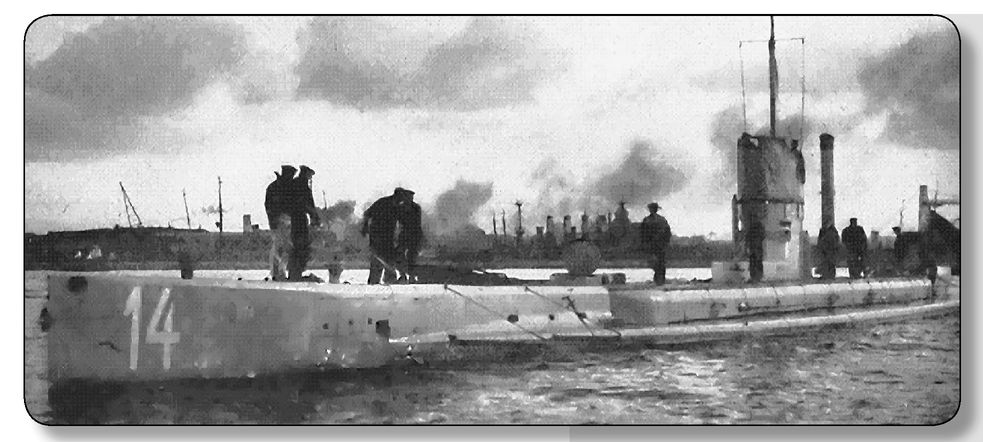

You will find in actual practice that if you trade as I have indicated any important piece of news given out between the closing of one market and the opening of another is usually in harmony with the line of least resistance. The trend has been established before the news is published, and in bull markets bear items are ignored and bull news exaggerated, and vice versa. Before the war broke out the market was in a very weak condition. There came the proclamation of Germany’s submarine policy.

I was short one hundred and fifty thou sand shares of stock, not because I knew the news was coming, but because I was going along the line of least resistance. What happened came out of a clear sky, as far as my play was concerned. Of course I took advantage of the situation and I cov ered my shorts that day.

It sounds very easy to say that all you have to do is to watch the tape, establish your resistance points and be ready to trade along the line of least resistance as soon as you have determined it. But in actual practice a man has to guard against many things, and most of all against himself—that is, against human nature. That is the reason why I say that the man who is right always has two forces working in his favor—basic conditions and the men who are wrong. In a bull market bear factors are ignored. That is human nature, and yet human be ings profess astonishment at it. People will tell you that the wheat crop has gone to pot because there has been bad weather in one or two sections and some farmers have been ruined. When the entire crop is gathered and all the farmers in all the wheat- growing sections begin to take their wheat to the elevators the bulls are surprised at the smallness of the damage. They discover that they merely have helped the bears.

When a man makes his play in a commodity market he must not permit himself set opinions. He must have an open mind and flexibility. It is not wise to disregard the message of the tape, no matter what your opinion of crop conditions or of the probable demand may be. I recall how I missed a big play just by trying to anticipate the starting signal. I felt so sure of conditions that I thought it was not necessary to wait for the line of least resistance to define itself. I even thought I might help it arrive, because it looked as if it merely needed a little assistance.

10.6Germany pioneered the development of submarines and their use in naval warfare, starting with the Brandtaucher in 1850. The Karp class of U-boats, called the U-1s, were the fi rst submarines specifi cally built for the German navy; they were powered with a kerosene engine and armed with one torpedo tube. Diesel engines were added in 1912.

At the start of World War I, Germany had 29 subs in service. They were used to sink British warships that had little defense against underwater attack. At first, the Germans avoided attacking British merchant ships, but by February 1915, fighting escalated and the kaiser proclaimed the area around the British Isles a war zone—ordering his captains to attack civilian commercial ships without warning. This naturally hit the world’s financial markets hard, allowing Livermore to take profits on short sales he had set in motion amid an already weak market.

President Woodrow Wilson then declared that he would hold Germany “to a strict accountability” for the loss of American lives and would take all steps necessary to safeguard American citizens’ rights on the high seas. The kaiser countered by declaring that neutral vessels entering the war zone would themselves bear responsibility for any “unfortunate accidents” that might occur.

5On May 7, 1915, a German U-20 sank the Lusitania with a torpedo, taking 1,198 lives, including the lives of 128 U.S. civilians. The American government severed diplomatic relations with Germany over the incident, and the German navy backed off attacking merchant ships for a while before announcing unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917. On March 17 of that year, U-boats sank three U.S. merchant ships. The United States declared war on Germany in April.

610.7 Livermore devotes much of his 1940 book, How to Trade in Stocks, to what he calls “the pivotal point”—his name for critical support and resistance levels. In addition to referring to the limits of a trading range, he believes a pivotal point can also be whole number milestones such as $50, $100, or $200. As he does frequently in Reminiscences, Livermore makes reference to his experiences with Anaconda to convey this point.

In the age long before computer analytics or online stock charts, Livermore used a complex system of notation written in red ink, black ink, and pencil on custom-printed pages of graph paper. With dates running down the left-hand column, prices would be recorded in one of six columns depending on the nature of the current movement: secondary rally, natural rally, upward trend, downward trend, natural reaction, and secondary reaction.

In the chart from his book, you can see the stock prices of both U.S. Steel and Bethlehem Steel are listed along with a “Key Price” entry. Here, Livermore would combine the movements of individual stocks to generate a trend for the group. This would protect him from false movements in individual stocks that would mask the actual trend. A modern interpretation of Livermore’s system would be to use sector-level indexes or exchange-traded funds to monitor the price behavior of industries.

I was very bullish on cotton. It was hanging around twelve cents, running up and down within a moderate range. It was in one of those in-between places and I could see it. I knew I really ought to wait.

But I got to thinking that if I gave it a little push it would go beyond the upper resistance point.

I bought fifty thousand bales. Sure enough, it moved up. And sure enough, as soon as I stopped buying it stopped going up. Then it began to settle back to where it was when I began buying it. I got out and it stopped going down. I thought I was now much nearer the starting signal, and presently I thought I’d start it myself again. I did. The same thing happened. I bid it up, only to see it go down when I stopped. I did this four or five times until I finally quit in disgust. It cost me about two hundred thousand dollars. I was done with it. It wasn’t very long after that when it began to go up and never stopped till it got to a price that would have meant a killing for me—if I hadn’t been in such a great hurry to start.

This experience has been the experience of so many traders so many times that I can give this rule: In a narrow market, when prices are not getting anywhere to speak of but move within a narrow range, there is no sense in trying to anticipate what the next big movement is going to be—up or down. The thing to do is to watch the market, read the tape to determine the limits of the get-nowhere prices, and make up your mind that you will not take an interest until the price breaks through the limit in either direction. A speculator must concern himself with making money out of the market and not with insisting that the tape must agree with him. Never argue with it or ask it for reasons or explanations. Stock-market post-mortems don’t pay dividends.

Not so long ago I was with a party of friends. They got to talking wheat. Some of them were bullish and others bearish. Finally they asked me what I thought. Well, I had been studying the market for some time. I knew they did not want any statistics or analyses of conditions. So I said: “If you want to make some money out of wheat I can tell you how to do it.”

They all said they did and I told them, “If you are sure you wish to make money in wheat just you watch it. Wait. The moment it crosses $1.20 buy it and you will get a nice quick play in it!”

“Why not buy it now, at $1.14?” one of the party asked.

“Because I don’t know yet that it is going up at all.”

“Then why buy it at $1.20? It seems a mighty high price.”

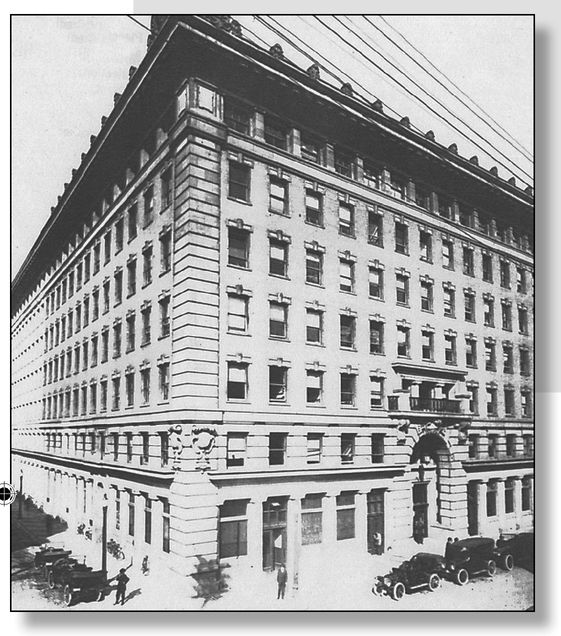

10.8 Manitoba was a major center of wheat production in North America, and the Winnipeg Commodity Exchange, established in 1887 and shown below, was a force in setting world prices in wheat futures after 1904. It is now the only agricultural commodities exchange in Canada.

7“Do you wish to gamble blindly in the hope of getting a great big profit or do you wish to speculate intelligently and get a smaller but much more probable profit?”

They all said they wanted the smaller but surer profit, so I said, “Then do as I tell you. If it crosses $1.20 buy.”

As I told you, I had watched it a long time. For months it sold between $1.10 and $1.20, getting nowhere in particular. Well, sir, one day it closed at above $1.19. I got ready for it. Sure enough the next day it opened at $1.20½, and I bought. It went to $1.21, to $1.22, to $1.23, to $1.25, and I went with it.

Now I couldn’t have told you at the time just what was going on. I didn’t get any explanations about its behaviour during the course of the limited fluctuations. I couldn’t tell whether the breaking through the limit would be up through $1.20 or down through $1.10, though I suspected it would be up because there was not enough wheat in the world for a big break in prices.

As a matter of fact, it seems Europe had been buying quietly and a lot of traders had gone short of it at around $1.19. Owing to the European purchases and other causes, a lot of wheat had been taken out of the market, so that finally the big movement got started. The price went beyond the $1.20 mark. That was all the point I had and it was all I needed. I knew that when it crossed $1.20 it would be because the upward movement at last had gathered force to push it over the limit and something had to happen. In other words, by crossing $1.20 the line of least resistance of wheat prices was established. It was a different story then.

I remember that one day was a holiday with us and all our markets were closed. Well, in Winnipeg wheat opened up six cents a bushel. 10.8 When our market opened on the following day, it also was up six cents a bushel. The price just went along the line of least resistance.

What I have told you gives you the essence of my trading system as based on studying the tape. I merely learn the way prices are most probably going to move. I check up my own trading by additional tests, to determine the psychological moment. I do that by watching the way the price acts after I begin.

It is surprising how many experienced traders there are who look incredulous when I tell them that when I buy stocks for a rise I like to pay top prices and when I sell I must sell low or not at all. It would not be so difficult to make money if a trader always stuck to his speculative guns—that is, waited for the line of least resistance to define itself and began buying only when the tape said up or selling only when it said down. He should accumulate his line on the way up. Let him buy one-fifth of his full line. If that does not show him a profit he must not increase his holdings because he has obviously begun wrong; he is wrong temporarily and there is no profit in being wrong at any time. The same tape that said up did not necessarily lie merely because it is now saying not yet.

In cotton I was very successful in my trading for a long time. I had my theory about it and I absolutely lived up to it. Suppose I had decided that my line would be forty to fifty thousand bales. Well, I would study the tape as I told you, watching for an opportunity either to buy or to sell. Suppose the line of least resistance indicated a bull movement. Well, I would buy ten thousand bales. After I got through buying that, if the market went up ten points over my initial purchase price, I would take on another ten thousand bales. Same thing. Then, if I could get twenty points’ profit, or one dollar a bale, I would buy twenty thousand more. That would give me my line—my basis for my trading. But if after buying the first ten or twenty thousand bales, it showed me a loss, out I’d go. I was wrong. It might be I was only temporarily wrong. But as I have said before it doesn’t pay to start wrong in anything.

10.9 In Lefevre’s view, Livermore traveled in a sea of colorful characters from whom he learned his trade a day at a time. In Reminiscences, Lefevre leans on the literary device of having these characters tell stories to Livermore so he can liven the narrative with new voices. In this section, he introduces a nameless old codger who tells Livermore about Pat Hearne, a “nervy chap” and professional gambler who deployed a system of pyramiding up a winning market bet while keeping a trailing stop in place one point below the price of his last purchase.

Hearne illustrates an important facet of Livermore’s game: He was not after tips for big 20-point advances but just sure money in sufficient quantities to provide him with a good living. He was a speculator who viewed the stock market as a game of chance that would yield to a sound betting method. Hearne would never directly answer tip seekers who asked about the wisdom of a prospective play and would instead relate a horse-racing maxim: “You can’t tell till you bet.” This was a succinct description of Livermore’s own philosophy.

What I accomplished by sticking to my system was that I always had a line of cotton in every real movement. In the course of accumulating my full line I might chip out fifty or sixty thousand dollars in these feeling-out plays of mine. This looks like a very expensive testing, but it wasn’t. After the real movement started, how long would it take me to make up the fifty thousand dollars I had dropped in order to make sure that I began to load up at exactly the right time? No time at all! It always pays a man to be right at the right time.

As I think I also said before, this describes what I may call my system for placing my bets. It is simple arithmetic to prove that it is a wise thing to have the big bet down only when you win, and when you lose to lose only a small exploratory bet, as it were. If a man trades in the way I have described, he will always be in the profitable position of being able to cash in on the big bet.

Professional traders have always had some system or other based upon their experience and governed either by their attitude toward speculation or by their desires. I remember I met an old gentleman in Palm Beach whose name I did not catch or did not at once identify. I knew he had been in the Street for years, way back in Civil War times, and somebody told me that he was a very wise old codger who had gone through so many booms and panics that he was always saying there was nothing new under the sun and least of all in the stock market.

The old fellow asked me a lot of questions. When I got through telling him about my usual practice in trading he nodded and said, “Yes! Yes! You’re right. The way you’re built, the way your mind runs, makes your system a good system for you. It comes easy for you to practice what you preach, because the money you bet is the least of your cares. I recollect Pat Hearne.

Ever hear of him? Well, he was a very well-known sporting man and he had an account with us. Clever chap and nervy. He made money in stocks, and that made people ask him for advice. He would never give any. If they asked him point-blank for his opinion about the wisdom of their commitments he used a favourite race-track maxim of his: ‘You can’t tell till you bet.’ He traded in our office. He would buy one hundred shares of some active stock and when, or if, it went up 1 per cent he would buy another hun dred. On another point’s advance, another hundred shares; and so on. He used to say he wasn’t playing the game to make money for others and therefore he would put in a stop-loss order one point below the price of his last purchase. When the price kept going up he simply moved up his stop with it. On a 1 per cent reaction he was stopped out. He declared he did not see any sense in losing more than one point, whether it came out of his original margin or out of his paper profits.

“You know, a professional gambler is not looking for long shots, but for sure money. Of course long shots are fine when they come in. In the stock market Pat wasn’t after tips or playing to catch twenty-points-a-week advances, but sure money in sufficient quantity to provide him with a good living. Of all the thousands of outsiders that I have run across in Wall Street, Pat Hearne was the only one who saw in stock speculation merely a game of chance like faro or roulette, but, nevertheless, had the sense to stick to a relatively sound betting method.

“After Hearne’s death one of our customers who had always traded with Pat and used his system made over one hundred thousand dollars in Lackawanna. Then he switched over to some other stock and because he had made a big stake he thought he need not stick to Pat’s way. When a reaction came, instead of cutting short his losses he let them run—as though they were profits. Of course every cent went. When he finally quit he owed us several thousand dollars.

10.10 William R. Travers was a very successful speculator and bon vivant in the post-Civil War era who played the market primarily as a short seller. He was also an avid horseman who cofounded the Saratoga Race Course in upstate New York; the track’s Travers Stakes, named for him, is the oldest Thoroughbred race in America. He was also a longtime president of the New York Athletic Club.

In his book, Fifty Years in Wall Street, financier Henry Clews devotes all of Chapter 33 to Travers, lauding his kind nature, inexhaustible supply of sparkling humor, and fondness for sports—personality traits that seemed more fitting a bull than a bear. The chapter is peppered with references to Travers’s stutter and wit. In one, a fellow transplant from Maryland tells the trader that he seems to stutter a great deal more than when he lived in Baltimore. “W-h-y, y-e-s,” replied Mr. Travers, darting a look of surprise at his friend; “of course I do. This is a d-d-damned sight b-b-bigger city.”

8

“He hung around for two or three years. He kept the fever long after the cash had gone; but we did not object as long as he behaved himself. I remember that he used to admit freely that he had been ten thousand kinds of an ass not to stick to Pat Hearne’s style of play. Well, one day he came to me greatly excited and asked me to let him sell some stock short in our office. He was a nice enough chap who had been a good customer in his day and I told him I personally would guarantee his account for one hundred shares.

“He sold short one hundred shares of Lake Shore. That was the time Bill Travers hammered the market, in 875.

My friend Roberts put out that Lake Shore at exactly the right time and kept selling it on the way down as he had been wont to do in the old successful days before he forsook Pat Hearne’s system and instead listened to hope’s whispers.

“Well, sir, in four days of successful pyramiding, Roberts’ account showed him a profit of fifteen thousand dollars. Observing that he had not put in a stop-loss order I spoke to him about it and he told me that the break hadn’t fairly begun and he wasn’t going to be shaken out by any one-point reaction. This was in August. Before the middle of September he borrowed ten dollars from me for a baby carriage—his fourth. He did not stick to his own proved system. That’s the trouble with most of them,” and the old fellow shook his head at me.

And he was right. I sometimes think that speculation must be an unnatural sort of business, because I find that the average speculator has arrayed against him his own nature. The weaknesses that all men are prone to are fatal to success in speculation—usually those very weaknesses that make him likable to his fellows or that he himself particularly guards against in those other ventures of his where they are not nearly so dangerous as when he is trading in stocks or commodities.

The speculator’s chief enemies are always boring from within. It is inseparable from human nature to hope and to fear. In speculation when the market goes against you you hope that every day will be the last day—and you lose more than you should had you not listened to hope—to the same ally that is so potent a success-bringer to empire builders and pioneers, big and little. And when the market goes your way you become fearful that the next day will take away your profit, and you get out—too soon. Fear keeps you from making as much money as you ought to. The successful trader has to fight these two deep-seated instincts. He has to reverse what you might call his natural impulses. Instead of hoping he must fear; instead of fearing he must hope. He must fear that his loss may develop into a much bigger loss, and hope that his profit may become a big profit. It is absolutely wrong to gamble in stocks the way the average man does.

I have been in the speculative game ever since I was fourteen. It is all I have ever done. I think I know what I am talking about. And the conclusion that I have reached after nearly thirty years of constant trading, both on a shoestring and with millions of dollars back of me, is this: A man may beat a stock or a group at a certain time, but no man living can beat the stock market! A man may make money out of individual deals in cotton or grain, but no man can beat the cotton market or the grain market. It’s like the track. A man may beat a horse race, but he cannot beat horse racing.

If I knew how to make these statements stronger or more emphatic I certainly would. It does not make any difference what anybody says to the contrary. I know I am right in saying these are incontrovertible statements.

ENDNOTES

1 “Funeral of Dickson G. Watts,”

New York Times, February 2, 1902.

2 Dickson G. Watts,

Speculation as a Fine Art and Thoughts on Life (Traders Press, 1965), 11.

4 Ed Holm,

Yachting’s Golden Age: 1880-1905 (New York: Knopf).

5 Charles Downer Hazen,

Fifty Years of Europe, 1870-1919 (New York: H. Holt & Co., 1919).

7 Michael Atkin,

Agricultural Commodity Markets: A Guide to Futures Trading (Routledge, 1989).

8 Henry Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, Part 1 (New York: Irving Publishing Company, 1908), 407.

I am crazy about fishing and I was due to have the time of my life. I looked forward to it and expected to go any day. But I did not. The market wouldn’t let me.

I am crazy about fishing and I was due to have the time of my life. I looked forward to it and expected to go any day. But I did not. The market wouldn’t let me. I am crazy about fishing and I was due to have the time of my life. I looked forward to it and expected to go any day. But I did not. The market wouldn’t let me.

I am crazy about fishing and I was due to have the time of my life. I looked forward to it and expected to go any day. But I did not. The market wouldn’t let me. There is no question about their greater legitimacy, as it were. It partakes more of the nature of a commercial venture than trading in stocks does. A man can approach it as he might any mercantile problem. It may be possible to use fictitious arguments for or against a certain trend in a commodity market; but success will be only temporary, for in the end the facts are bound to prevail, so that a trader gets dividends on study and observation, as he does in a regular business. He can watch and weigh conditions and he knows as much about it as anyone else. He need not guard against inside cliques. Dividends are not unexpectedly passed or increased overnight in the cotton market or in wheat or corn. In the long run commodity prices are governed but by one law—the economic law of demand and supply. The business of the trader in commodities is simply to get facts about the demand and the supply, present and prospective. He does not indulge in guesses about a dozen things as he does in stocks. It always appealed to me—trading in commodities.

There is no question about their greater legitimacy, as it were. It partakes more of the nature of a commercial venture than trading in stocks does. A man can approach it as he might any mercantile problem. It may be possible to use fictitious arguments for or against a certain trend in a commodity market; but success will be only temporary, for in the end the facts are bound to prevail, so that a trader gets dividends on study and observation, as he does in a regular business. He can watch and weigh conditions and he knows as much about it as anyone else. He need not guard against inside cliques. Dividends are not unexpectedly passed or increased overnight in the cotton market or in wheat or corn. In the long run commodity prices are governed but by one law—the economic law of demand and supply. The business of the trader in commodities is simply to get facts about the demand and the supply, present and prospective. He does not indulge in guesses about a dozen things as he does in stocks. It always appealed to me—trading in commodities. They will do whatever comes easiest, therefore they will go up if there is less resistance to an advance than to a decline; and vice versa.

They will do whatever comes easiest, therefore they will go up if there is less resistance to an advance than to a decline; and vice versa. I was short one hundred and fifty thou sand shares of stock, not because I knew the news was coming, but because I was going along the line of least resistance. What happened came out of a clear sky, as far as my play was concerned. Of course I took advantage of the situation and I cov ered my shorts that day.

I was short one hundred and fifty thou sand shares of stock, not because I knew the news was coming, but because I was going along the line of least resistance. What happened came out of a clear sky, as far as my play was concerned. Of course I took advantage of the situation and I cov ered my shorts that day.

But I got to thinking that if I gave it a little push it would go beyond the upper resistance point.

But I got to thinking that if I gave it a little push it would go beyond the upper resistance point.

Ever hear of him? Well, he was a very well-known sporting man and he had an account with us. Clever chap and nervy. He made money in stocks, and that made people ask him for advice. He would never give any. If they asked him point-blank for his opinion about the wisdom of their commitments he used a favourite race-track maxim of his: ‘You can’t tell till you bet.’ He traded in our office. He would buy one hundred shares of some active stock and when, or if, it went up 1 per cent he would buy another hun dred. On another point’s advance, another hundred shares; and so on. He used to say he wasn’t playing the game to make money for others and therefore he would put in a stop-loss order one point below the price of his last purchase. When the price kept going up he simply moved up his stop with it. On a 1 per cent reaction he was stopped out. He declared he did not see any sense in losing more than one point, whether it came out of his original margin or out of his paper profits.

Ever hear of him? Well, he was a very well-known sporting man and he had an account with us. Clever chap and nervy. He made money in stocks, and that made people ask him for advice. He would never give any. If they asked him point-blank for his opinion about the wisdom of their commitments he used a favourite race-track maxim of his: ‘You can’t tell till you bet.’ He traded in our office. He would buy one hundred shares of some active stock and when, or if, it went up 1 per cent he would buy another hun dred. On another point’s advance, another hundred shares; and so on. He used to say he wasn’t playing the game to make money for others and therefore he would put in a stop-loss order one point below the price of his last purchase. When the price kept going up he simply moved up his stop with it. On a 1 per cent reaction he was stopped out. He declared he did not see any sense in losing more than one point, whether it came out of his original margin or out of his paper profits.

My friend Roberts put out that Lake Shore at exactly the right time and kept selling it on the way down as he had been wont to do in the old successful days before he forsook Pat Hearne’s system and instead listened to hope’s whispers.

My friend Roberts put out that Lake Shore at exactly the right time and kept selling it on the way down as he had been wont to do in the old successful days before he forsook Pat Hearne’s system and instead listened to hope’s whispers.