XI

And now I’ll get back to October, 1907. I bought a yacht and made all preparations to leave New York for a cruise in Southern waters. I am really daffy about fishing and this was the time when I was going to fish to my heart’s content from my own yacht, going wherever I wished whenever I felt like it. Everything was ready. I had made a killing in stocks, but at the last moment corn held me back.

I must explain that before the money panic which gave me my first million I had been trading in grain at Chicago.

I was short ten million bushels of wheat and ten million bushels of corn. I had studied the grain markets for a long time and was as bearish on corn and wheat as I had been on stocks.

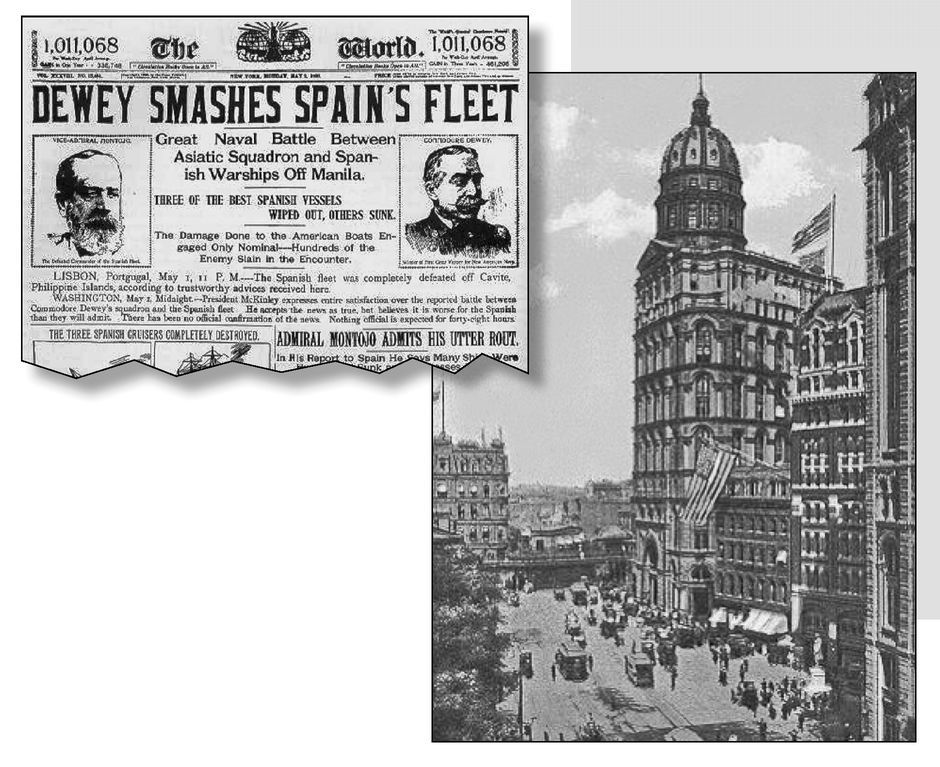

11.1 Livermore quickly became something of a celebrity after his exploits from the Panic of 1907 netted him more than $3 million over six weeks. The Chicago Daily Tribune wrote that this “beardless fortune hunter of 28” had “waited five years to make money in this bewildering way.”

1The Boston Daily Globe said that “young Livermore read the signs of the big slump in stocks” and “hit market right.” Livermore gave one of the fi rst in a long line of interviews to newspapermen. “I prefer not to discuss my personal affairs,” he said. “Few men in Wall St. know me, and I prefer not to be known. When a man has been successful down there, Wall St. is looking for him. There are those who have won fortunes in the markets and heralded their success. I prefer to enjoy my gains as quietly as I won them.”

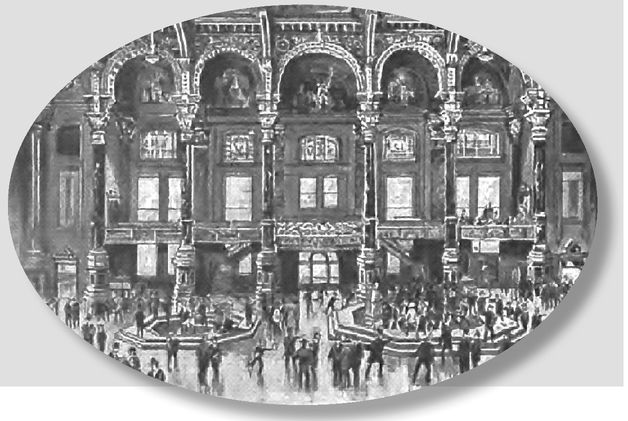

211.2 Livermore is referring to the Chicago Board of Trade, which was founded in 1848 and is the world’s oldest futures exchange. Although he could have traded in grains in New York through the Produce Exchange, trading volume in Chicago soon eclipsed that of New York due to its proximity to the Midwestern growing region and its importance as a railroad hub. Also key: the ability to ship product for export south to New Orleans via the Mississippi River or north out of the Great Lakes through the St. Lawrence River, avoiding the Erie Canal or the overland route to the port of New York.

Throughout 1907, there was great excitement in Chicago as commodity prices rose. Starting in February, unfavorable crop reports from Argentina helped push up wheat, corn, and oats contracts. The rise accelerated as shorts were forced to cover on reports that Russia was conserving its grain to fight famine within its borders. Then over the spring came word of insect ravages and idled farm acreage, resulting in more short covering. As prices continued to advance, arket was “one of the wildest, largest and most excited and well sustained the Board of Trade has ever known,” accordi to Charles Taylor’s memoirs from 1917.

3It was at this time that Livermore saw his opportunity to go short. According to Taylor, most of the excited buying was coming from the public—not professional traders. By May, the “market was almost in a state of hysteria, there was wild cheering when September wheat passed the coveted $1 mark, women in the gallery wept and shouted without knowing exactly why and traders were overwhelmed .... It seemed that the whole world was in the market buying wheat.”

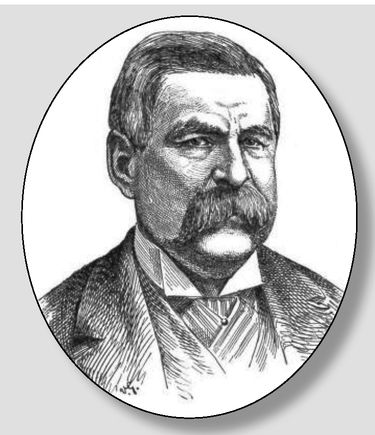

411.3 “Stratton” appears to be a pseudonym for

James A. Patten, a notorious Chi cago speculator. Patten was born in a farming community in 1852, and got his start as a clerk in a country store before receiving an appointment as a clerk in the office of the State Grain Inspector’s office in Chicago. Later he started, along with his brother, the brokerage firm of Patten Brothers, which attracted international attention.

5In one high-profile spat in 1909, Patten exchanged jibes through the newspaper with the U.S. secretary of agriculture, James Wilson. At issue was Patten’s manipulation of wheat prices during a corner earlier that year, which Wilson claimed artificially raised prices despite plentiful supply. Patten was soon blamed for inciting bread riots, and bomb threats forced him to hire two bodyguards. Preachers called him “the God of Get.”

6 Later, in 1911, he tried cornering cotton and was mobbed in Liverpool at the height of a panic.

7Just before embarking on his corn corner, Patten went west in July 1907 to study crop conditions firsthand.

8Well, they both started down, but while wheat kept on declining the biggest of all the Chicago operators—I’ll call him Stratton—took it into his head to run a corner in corn.

After I cleaned up in stocks and was ready to go South on my yacht I found that wheat showed me a handsome profit, but in corn Stratton had run up the price and I had quite a loss.

I knew there was much more corn in the country than the price indicated. The law of demand and supply worked as always. But the demand came chiefly from Stratton and the supply was not coming at all, because there was an acute congestion in the movement of corn. I remember that I used to pray for a cold spell that would freeze the impassable roads and enable the farmers to bring their corn into the market. But no such luck.

There I was, waiting to go on my joyously planned fishing trip and that loss in corn holding me back. I couldn’t go away with the market as it was. Of course Stratton kept pretty close tabs on the short interest. He knew he had me, and I knew it quite as well as he did. But, as I said, I was hoping I might convince the weather that it ought to get busy and help me. Perceiving that neither the weather nor any other kindly wonder-worker was paying any attention to my needs I studied how I might work out of my difficulty by my own efforts.

I closed out my line of wheat at a good profit. But the problem in corn was infinitely more difficult. If I could have covered my ten million bushels at the prevailing prices I instantly and gladly would have done so, large though the loss would have been. But, of course, the moment I started to buy in my corn Stratton would be on the job as squeezer in chief, and I no more relished running up the price on myself by reason of my own purchases than cutting my own throat with my own knife.

Strong though corn was, my desire to go fishing was even stronger, so it was up to me to find a way out at once. I must conduct a strategic retreat. I must buy back the ten million bushels I was short of and in so doing keep down my loss as much as I possibly could.

It so happened that Stratton at that time was also running a deal in oats and had the market pretty well sewed up. I had kept track of all the grain markets in the way of crop news and pit gossip, and I heard that the powerful Armour interests were not friendly, marketwise, to Stratton.

Of course I knew that Stratton would not let me have the corn I needed except at his own price, but the moment I heard the rumors about Armour being against Stratton it occurred to me that I might look to the Chicago traders for aid. The only way in which they could possibly help me was for them to sell me the corn that Stratton wouldn’t. The rest was easy.

11.4While Patten was running a corner in corn,

Jonathan Ogden Armour—better known as J. Ogden—was running a parallel corner in wheat.

9 The Armour family operated the large Armour & Co. meatpacking business that was the inspiration for Upton Sinclair’s exposé of the industry, The Jungle. The company was criticized for furnishing rotten meat to soldiers during the Spanish-American War. J. Ogden’s father, Philip D. Armour, started the company in the mid-1800s after driving cattle, mining gold, and shorting pork just as the Civil War was coming to an end—netting $2 million from all his endeavors with which to expand his meatpacking empire.

10

From this early adventure in speculation, the Armours developed something of a family tradition. The senior Armour went on to corner pork three separate times. To explain the practice, banker and historian Henry Clews wrote: “A campaign against the bears in pork or meats he calls protecting his cellars.”

11 Philip Armour made millions in grain speculation, and dabbled in railroads after purchasing the St. Paul railroad on the open market for $4 million.

After the deaths of his father and brother, J. Ogden took the reins of Armour & Co. in 1901 and expanded its business greatly. The company collapsed in the economic downturn that followed World War I. As a result, along with losses on his other investments, J. Ogden lost his family’s fortune, which was estimated at the time to be the world’s second largest. He bravely declared: “I do not mind the loss, for I have regained my health.” But fate was cruel. Within a few months, he lost that too, dying of heart failure.

12

11.5 The record shows unusually active speculation in commodities in Chicago throughout October. There were “fierce battles in the corn pit, both corn and wheat being upheld by the heavy buying by Patten,” according to a historian.

13 For delivery in December, wheat contracts fell from $107¾ to $94 5/8 while corn fell from $64 7/8 to $55 and oats collapsed from $56 to $44. However, the drop “stimulated an active export demand for grain” as overseas crops were ravaged by bad weather, causing prices to recover.

14Until the corners were complete the following May, Patten and Armour were locked in a running battle: Armour caught Patten short in wheat; Patten similarly caught Armour, who was one of the largest shorts in the corn market.

15 The two corners ended on May 29 upon the expiration of May futures contracts without a crash or panic. Both reaped large profits by the two deals, with Patten’s winnings estimated at $2 million.

16

11.6

Addison Cammack, was a great Wall Street bear of the Civil War era. On occasion, he would team with Jay Gould and James Keene. He was close to William Travers, with whom he shared an office on 23rd Street in Manhattan.

17Cammack was born in 1826 in Kentucky in what was then America’s western frontier. His father was of Scottish descent and had grown tobacco in Virginia before becoming a gentleman farmer. At the age of 16, Cammack went to New Orleans to become an office boy. By 1861, he had become a senior partner in the firm, which changed its name to Cammack & Converse. During the Civil War, the firm relocated its headquarters to Havana and controlled a fleet of blockade runners that penetrated the Union navy’s

First, I put in orders to buy five hundred thousand bushels of corn every eighth of a cent down. After these orders were in I gave to each of four houses an order to sell simultaneously fifty thousand bushels of oats at the market. That, I figured, ought to make a quick break in oats. Knowing how the traders’ minds worked, it was a cinch that they would instantly think that Armour was gunning for Stratton. Seeing the attack opened in oats they would logically conclude that the next break would be in corn and they would start to sell it. If that corner in corn was busted, the pickings would be fabulous.

My dope on the psychology of the Chicago traders was absolutely correct. When they saw oats breaking on the scattered selling they promptly jumped on corn and sold it with great enthusiasm. I was able to buy six million bushels of corn in the next ten minutes. The moment I found that their selling of corn ceased I simply bought in the other four million bushels at the market. Of course that made the price go up again, but the net result of my manœuvre was that I covered the entire line of ten million bushels within one-half cent of the price prevailing at the time I started to cover on the traders’ selling. The two hundred thousand bushels of oats that I sold short to start the traders’ selling of corn I covered at a loss of only three thousand dollars. That was pretty cheap bear bait. The profits I had made in wheat offset so much of my deficit in corn that my total loss on all my grain trades that time was only twenty-five thousand dollars. Afterwards corn went up twenty-five cents a bushel. Stratton undoubtedly had me at his mercy. If I had set about buying my ten million bushels of corn without bothering to think of the price there is no telling what I would have had to pay.

A man can’t spend years at one thing and not acquire a habitual attitude towards it quite unlike that of the average beginner. The difference distinguishes the professional from the amateur. It is the way a man looks at things that makes or loses money for him in the speculative markets. The public has the dilettante’s point of view toward his own effort. The ego obtrudes itself unduly and the thinking therefore is not deep or exhaustive. The professional concerns himself with doing the right thing rather than with making money, knowing that the profit takes care of itself if the other things are attended to. A trader gets to play the game as the professional billiard player does—that is, he looks far ahead instead of considering the particular shot before him. It gets to be an instinct to play for position.

I remember hearing a story about Addison Cammack that illustrates very nicely what I wish to point out.

From all I have heard, I am inclined to think that Cammack was one of the ablest stock traders the Street ever saw. He was not a chronic bear as many believe, but he felt the greater appeal of trading on the bear side, of utilising in his behalf the two great human factors of hope and fear. He is credited with coining the warning: “Don’t sell stocks when the sap is running up the trees!” and the old-timers tell me that his biggest winnings were made on the bull side, so that it is plain he did not play prejudices but conditions. At all events, he was a consummate trader. It seems that once—this was way back at the tag end of a bull market—Cammack was bearish, and J. Arthur Joseph, the financial writer and raconteur, knew it. The market, however, was not only strong but still rising, in response to prodding by the bull leaders and optimistic reports by the newspapers. Knowing what use a trader like Cammack could make of bearish information, Joseph rushed to Cammack’s office one day with glad tidings.

“Mr. Cammack, I have a very good friend who is a transfer clerk in the St. Paul office and he has just told me something which I think you ought to know.”

“What is it?” asked Cammack listlessly.

defenses with varying degrees of success in an attempt to smuggle war provisions.

After the war, Cammack moved to New York City to run a whisky distribution business before leaving for Europe in 1867 for three years. Upon his return, he formed and ran the brokerage Osborne & Cammack for a short time, of which Jay Gould was a special partner, before it was dissolved in 1873. After studying the art of stock brokering, Cammack was ready to take on Wall Street as an operator.

He joined the NYSE in 1875 and quickly earned the Latin nickname “Ursa Major,” or great bear. According to the New York Times, Cammack’s successes in the 1880s came from his methodical research and careful planning: “Few Wall Street men have had his thorough knowledge of railroad matters. He often had the figures of railroad earnings before they reached the offices of the companies.”

18Cammack sold his exchange seat in 1897 and retired to the embrace of his family. His fortune was estimated to be $1.2 million at the time. He died in 1901 from kidney problems.

19 When asked for the keys to his success, Cammack would answer: “Luck, sir; chiefly luck. Perhaps caution, too. I never overtrade and don’t like big losses. I don’t think I ever took a big loss in my life. Then again I don’t spend much. My habits are very quiet and inexpensive. That is about all, sir.”

20Lefevre, writing in the Saturday Evening Post in 1915, used Cammack as an example of his view that the speculation game was unwinnable:

The late Addison Cammack, the great bear operator in Wall Street, after many years of battling and after some spectacular successes and unadvertised failures, did not leave an estate that consisted of the winnings on the bear side. One of his intimate friends told me that if it had not been for fortunate investments Cammack would not have died rich.

21That was pretty uncharitable. The New York Times reported in 1909 that S. V. White said Cammack had left his widow a rather sizable annual income of $50,000 from a fortune earned on both the long and the short sides of the market.

2211.7 W. B. Wheeler was one of the most active brokerages on Wall Street in the 1880s and early 1890s. Its founder, William B. Wheeler, was called a “bold and successful” operator in his own right, and Addison Cammack thought enough of his “pluck and judgment,” according to the New York Times, that he traded a joint account with him.

Wheeler, said to have a “genial disposition,” preferred trading on his own to dealing on behalf of customers, primarily on the short side of the market. He got in trouble in 1895 when he shorted a declining market heavily and then saw stocks rebound rapidly before he could cover. His resources “became practically exhausted,” according to the Times, so he had to borrow money from another dealer and a relative. When he couldn’t pay a margin call, the fragility of his position was exposed to his clients—and they shunned his firm. He was forced to close the broker age in April 1896.

Wheeler was one of the early corporate backers of the New York Giants, the baseball team that later moved to San Francisco. The Times reported that “it was his habit to take his office force and enough others to make a good party to every game at the Polo Grounds.”

“You’ve turned, haven’t you? You are bearish now?” asked Joseph, to make sure. If Cammack wasn’t interested he wasn’t going to waste precious ammunition.

“Yes. What’s the wonderful information?”

“I went around to the St. Paul office to-day, as I do in my news-gathering rounds two or three times a week, and my friend there said to me: ‘The Old Man is selling stock.’ He meant William Rockefeller. ‘Is he really, Jimmy?’ I said to him, and he answered, ‘Yes; he is selling fifteen hundred shares every three-eighths of a point up. I’ve been transferring the stock for two or three days now.’ I didn’t lose any time, but came right over to tell you.”

Cammack was not easily excited, and, moreover, was so accustomed to having all manner of people rush madly into his office with all manner of news, gossip, rumors, tips and lies that he had grown distrustful of them all. He merely said now, “Are you sure you heard right, Joseph?”

“Am I sure? Certainly I am sure! Do you think I am deaf?” said Joseph.

“Are you sure of your man?”

“Absolutely!” declared Joseph. “I’ve known him for years. He has never lied to me. He wouldn’t! No object! I know he is absolutely reliable and I’d stake my life on what he tells me. I know him as well as I know anybody in this world—a great deal better than you seem to know me, after all these years.”

“Sure of him, eh?” And Cammack again looked at Joseph. Then he said, “Well, you ought to know.” He called his broker, W. B. Wheeler.

Joseph expected to hear him give an order to sell at least fifty thousand shares of St. Paul. William Rockefeller was disposing of his holdings in St. Paul, taking advantage of the strength of the market. Whether it was investment stock or speculative holdings was irrelevant. The one important fact was that the best stock trader of the Standard Oil crowd was getting out of St. Paul. What would the average man have done if he had received the news from a trustworthy source? No need to ask.

But Cammack, the ablest bear operator of his day, who was bearish on the market just then, said to his broker, “Billy, go over to the board and buy fifteen hundred St. Paul every three-eighths up.” The stock was then in the nineties.

“Don’t you mean sell?” interjected Joseph hastily. He was no novice in Wall Street, but he was thinking of the market from the point of view of the newspaper man and, incidentally, of the general public. The price certainly ought to go down on the news of inside selling. And there was no better inside selling than Mr. William Rockefeller’s. The Standard Oil getting out and Cammack buying! It couldn’t be!

“No,” said Cammack; “I mean buy!”

“Don’t you believe me?”

“Yes!”

“Don’t you believe my information?”

“Yes.”

“Aren’t you bearish?”

“Yes.”

“Well, then?”

“That’s why I’m buying. Listen to me now: You keep in touch with that reliable friend of yours and the moment the scaled selling stops, let me know. Instantly! Do you understand?”

“Yes,” said Joseph, and went away, not quite sure he could fathom Cammack’s motives in buying William Rockefeller’s stock. It was the knowledge that Cammack was bearish on the entire market that made his manœuvre so difficult to explain. However, Joseph saw his friend the transfer clerk and told him he wanted to be tipped off when the Old Man got through selling. Regularly twice a day Joseph called on his friend to inquire.

One day the transfer clerk told him, “There isn’t any more stock coming from the Old Man.” Joseph thanked him and ran to Cammack’s office with the information.

11.8 Grangers were railroads whose principal business was carrying farmers’ produce to market. Examples include the Milwaukee & St. Paul, the Burlington & Quincey, and the Chicago & Alton.

Cammack listened attentively, turned to Wheeler and asked, “Billy, how much St. Paul have we got in the office?” Wheeler looked it up and reported that they had accumulated about sixty thousand shares.

Cammack, being bearish, had been putting out short lines in the other Grangers as well as in various other stocks, even before he began to buy St. Paul. 11.8 He was now heavily short of the market. He promptly ordered Wheeler to sell the sixty thousand shares of St. Paul that they were long of, and more besides. He used his long holdings of St. Paul as a lever to depress the general list and greatly benefit his operations for a decline.

St. Paul didn’t stop on that move until it reached forty-four and Cammack made a killing in it. He played his cards with consummate skill and profited accordingly. The point I would make is his habitual attitude toward trading. He didn’t have to reflect. He saw instantly what was far more important to him than his profit on that one stock. He saw that he had providentially been offered an opportunity to begin his big bear operations not only at the proper time but with a proper initial push. The St. Paul tip made him buy instead of sell because he saw at once that it gave him a vast supply of the best ammunition for his bear campaign.

To get back to myself. After I closed my trade in wheat and corn I went South in my yacht. I cruised about in Florida waters, having a grand old time. The fishing was great. Everything was lovely. I didn’t have a care in the world and I wasn’t looking for any.

One day I went ashore at Palm Beach. I met a lot of Wall Street friends and others. They were all talking about the most picturesque cotton speculator of the day. A report from New York had it that Percy Thomas had lost every cent. It wasn’t a commercial bankruptcy; merely the rumor of the world-famous operator’s second Waterloo in the cotton market.

I had always felt a great admiration for him. The first I ever heard of him was through the newspapers at the time of the failure of the Stock Exchange house of Sheldon & Thomas, when Thomas tried to corner cotton. Sheldon, who did not have the vision or the courage of his partner, got cold feet on the very verge of success. At least, so the Street said at the time. At all events, instead of making a killing they made one of the most sensational failures in years. I forget how many millions. The firm was wound up and Thomas went to work alone. He devoted himself exclusively to cotton and it was not long before he was on his feet again. He paid off his creditors in full with interest—debts he was not legally obliged to discharge—and withal had a million dollars left for himself. His comeback in the cotton market was in its way as remarkable as Deacon S. V. White’s famous stock-market exploit of paying off one million dollars in one year. Thomas’ pluck and brains made me admire him immensely.

Everybody in Palm Beach was talking about the collapse of Thomas’ deal in March cotton. You know how the talk goes—and grows; the amount of misinformation and exaggeration and improvements that you hear. Why, I’ve seen a rumor about myself grow so that the fellow who started it did not recognise it when it came back to him in less than twenty-four hours, swollen with new and picturesque details.

The news of Percy Thomas’ latest misadventure turned my mind from the fishing to the cotton market. I got files of the trade papers and read them to get a line on conditions. When I got back to New York I gave myself up to studying the market. Everybody was bearish and everybody was selling July cotton. You know how people are. I suppose it is the contagion of example that makes a man do something because everybody around him is doing the same thing. Perhaps it is some phase or variety of the herd instinct. In any case it was, in the opinion of hundreds of traders, the wise and proper thing to sell July cotton—and so safe too! You couldn’t call that general selling reckless; the word is too conservative. The traders simply saw one side to the market and a great big profit. They certainly expected a collapse in prices.

11.9 The cotton crop was plentiful in 1908. Some 13.5 million bales of 500 pounds each were harvested in the United States. At an average price of 9.2 cents a pound, the entire crop was worth more than $625 million.

23

I saw all this, of course, and it struck me that the chaps who were short didn’t have a terrible lot of time to cover in. The more I studied the situation the clearer I saw this, until I finally decided to buy July cotton. I went to work and quickly bought one hundred thousand bales. I experienced no trouble in getting it because it came from so many sellers. It seemed to me that I could have offered a reward of one million dollars for the capture, dead or alive, of a single trader who was not selling July cotton and nobody would have claimed it.

I should say this was in the latter part of May. I kept buying more and they kept on selling it to me until I had picked up all the floating contracts and I had one hundred and twenty thousand bales. A couple of days after I had bought the last of it it began to go up. Once it started the market was kind enough to keep on doing very well indeed—that is, it went up from forty to fifty points a day.

One Saturday—this was about ten days after I began operations—the price began to creep up. I did not know whether there was any more July cotton for sale. It was up to me to find out, so I waited until the last ten minutes. At that time, I knew, it was usual for those fellows to be short and if the market closed up for the day they would be safely hooked. So I sent in four different orders to buy five thousand bales each, at the market, at the same time. That ran the price up thirty points and the shorts were doing their best to wriggle away. The market closed at the top. All I did, remember, was to buy that last twenty thousand bales.

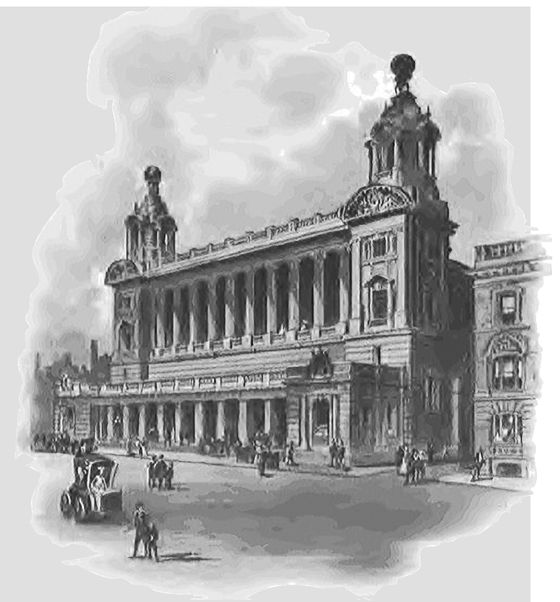

11.10 The advent of organized exchanges made it unnecessary for mills, which were concentrated in New England and Europe, to deal directly with cotton growers in America’s southern states. This was important in the years following the Civil War, when prices fluctuated dramatically and the transportation networks were undeveloped.

There were a number of smaller exchanges in Houston, Texas, and Mobile, Alabama, but a majority of the trading volume was relegated to the cotton exchanges in New Orleans and in New York City. Global trade was concentrated at the Liverpool Cotton Exchange, shown at right, which handled nearly all foreign trade in the fiber.

24 Liverpool was a key transaction point for American exports headed to textile mills in nearby Manchester in the northern reaches of England.

Because of the large quantities of cotton dealt with in Liverpool, and the fact that the market absorbed surplus production, global cotton prices tended to gravitate toward the price in Liverpool. Said one observer: “If…every producing country has a large crop, Liverpool does not have to pay much to attract wheat. If, on the other hand, all producers have small crops, Liverpool must pay exorbitantly.”

25 Like Chicago, Liverpool was an active center for the exchange of all types of commodities.

The Liverpool Cotton Exchange was formed after the so-called cotton famine of the 1860s, when exports from America were curtailed because of the Civil War and the Union navy’s blockade of southern ports. According to a cotton industry historian, the origin of the organization can be traced to a Sir George Drinkwater who, in September 1766, “sold a quantity of damaged cotton saved of the Molly, from Granada, which vessel was accidentally set on fire in the river, owing to the carelessness of the Excise officers, who had gone into the hold to rummage with a lighted candle.”

26LIVERPOOL COTTON ASSOCIATION, LIMITED.

The next day was Sunday. But on Monday, Liverpool was due to open up twenty points to be on a parity with the advance in New York. 11.10 Instead, it came fifty points higher. That meant that Liverpool had exceeded our advance by 100 per cent. I had nothing to do with the rise in that market. This showed me that my deductions had been sound and that I was trading along the line of least resistance. At the same time I was not losing sight of the fact that I had a whopping big line to dispose of. A market may advance sharply or rise gradually and yet not possess the power to absorb more than a certain amount of selling.

11.11 With this move, which cleared him some $2 million, Livermore added to his notoriety.

27Just as Livermore describes, July cotton was very weak in the spring of 1908. The New York Times wrote on April 8 that cotton was “active on continued weakness —closes 12 to 21 points down” on poor trade reports, good weather in the South, and rumors of an increase in planted acreage.

28 By mid-May, the situation reversed as Livermore put out his line. A “big rise in July cotton” was reported.

29 Traders at the New York Cotton Exchange no doubt scratched their heads in wonderment as the July contracts “kept climbing…and eventually the entire list felt its strength.”

30The move continued. On May 14, newspapers wrote of a $2.50-per-bale advance in July cotton—bringing the total rise from the recent low to $9.90. The market started to get suspicious, according to a reporter: “The advance was called a ‘corner,’ made possible by the strength of the Southern market.”

31 The next day, Livermore was fingered as possibly being responsible for the rise. The market in Liverpool became active as spinners, who had let their raw cotton stocks dwindle to dangerously low levels, were forced to make bids on fears “spot and nearby delivery had been cornered.”

32 It is at this point that Livermore is said to have started unloading his position.

By the end of June, after Livermore had gone back to cash, July cotton collapsed. Prices moved down to $6.40 per bale as a bull clique in New Orleans was rumored to have been routed: “Selling by the coterie of brokers who have been credit with creating practically a corner in July cotton in this market, was explained by a picturesque story that the sudden illness of one of the operators had thrown his associates into a panic and started them selling out on one another.”

33 We will never know if there is some truth to this, or if Livermore was just throwing the bears off his scent.

Of course the Liverpool cables made our own market wild. But I noticed the higher it went the scarcer July cotton seemed to be. I wasn’t letting go any of mine. Altogether that Monday was an exciting and not very cheerful day for the bears; but for all that, I could detect no signs of an impending bear panic; no beginnings of a blind stampede to cover. And I had one hundred and forty thousand bales for which I must find a market.

On Tuesday morning as I was walking to my office I met a friend at the entrance of the building.

“That was quite a story in the World this morning,” he said with a smile.

“What story?” I asked.

“What? Do you mean to tell me you haven’t seen it?”

“I never see the World,” I said. “What is the story?”

“Why, it’s all about you. It says you’ve got July cotton cornered.” 11.11

“I haven’t seen it,” I told him and left him. I don’t know whether he believed me or not. He probably thought it was highly inconsiderate of me not to tell him whether it was true or not.

When I got to the office I sent out for a copy of the paper. Sure enough, there it was, on the front page, in big headlines:

JULY COTTON CORNERED BY LARRY LIVINGSTON

Of course I knew at once that the article would play the dickens with the market. If I had deliberately studied ways and means of disposing of my one hundred and forty thousand bales to the best advantage I couldn’t have hit upon a better plan. It would not have been possible to find one. That article at that very moment was being read all over the country either in the World or in other papers quoting it. It had been cabled to Europe. That was plain from the Liverpool prices. That market was simply wild. No wonder, with such news.

Of course I knew what New York would do, and what I ought to do. The market here opened at ten o’clock. At ten minutes after ten I did not own any cotton. I let them have every one of my one hundred and forty thousand bales. For most of my line I received what proved to be the top prices of the day. The traders made the market for me. All I really did was to see a heaven-sent opportunity to get rid of my cotton. I grasped it because I couldn’t help it. What else could I do?

The problem that I knew would take a great deal of hard thinking to solve was thus solved for me by an accident. If the World had not published that article I never would have been able to dispose of my line without sacrificing the greater portion of my paper profits. Selling one hundred and forty thousand bales of July cotton without sending the price down was a trick beyond my powers. But the World story turned it for me very nicely.

Why the World published it I cannot tell you. I never knew. I suppose the writer was tipped off by some friend in the cotton market and he thought he was printing a scoop. I didn’t see him or anybody from the World. I didn’t know it was printed that morning until after nine o’clock; and if it had not been for my friend calling my attention to it I would not have known it then.

Without it I wouldn’t have had a market big enough to unload in. That is one trouble about trading on a large scale. You cannot sneak out as you can when you pike along. You cannot always sell out when you wish or when you think it wise. You have to get out when you can; when you have a market that will absorb your entire line. Failure to grasp the opportunity to get out may cost you millions. You cannot hesitate. If you do you are lost. Neither can you try stunts like running up the price on the bears by means of competitive buying, for you may thereby reduce the absorbing capacity. And I want to tell you that perceiving your opportunity is not as easy as it sounds. A man must be on the lookout so alertly that when his chance sticks in its head at his door he must grab it.

Of course not everybody knew about my fortunate accident. In Wall Street, and, for that matter, everywhere else, any accident that makes big money for a man is regarded with suspicion. When the accident is unprofitable it is never considered an accident but the logical outcome of your hoggishness or of the swelled head. But when there is a profit they call it loot and talk about how well unscrupulousness fares, and how ill conservatism and decency.

It was not only the evil-minded shorts smarting under punishment brought about by their own recklessness who accused me of having deliberately planned the coup. Other people thought the same thing.

One of the biggest men in cotton in the entire world met me a day or two later and said, “That was certainly the slickest deal you ever put over, Livingston. I was wondering how much you were going to lose when you came to market that line of yours. You knew this market was not big enough to take more than fifty or sixty thousand bales without selling off, and how you were going to work off the rest and not lose all your paper profits was beginning to interest me. I didn’t think of your scheme. It certainly was slick.”

“I had nothing to do with it,” I assured him as earnestly as I could.

But all he did was to repeat: “Mighty slick, my boy. Mighty slick! Don’t be so modest!”

It was after that deal that some of the papers referred to me as the Cotton King. But, as I said, I really was not entitled to that crown. It is not necessary to tell you that there is not enough money in the United States to buy the columns of the New York

World

or enough personal pull to secure the publication of a story like that. It gave me an utterly unearned reputation that time.

But I have not told this story to moralize on the crowns that are sometimes pressed down upon the brows of undeserving traders or to emphasize the need of seizing the opportunity, no matter when or how it comes. My object merely was to account for the vast amount of newspaper notoriety that came to me as the result of my deal in July cotton. If it hadn’t been for the newspapers I never would have met that remarkable man, Percy Thomas.

11.12 The New York World was one of the most popular newspapers of the era. Founded in 1860, it was purchased by Joseph Pulitzer in 1883 and became an innovator of many of the forms of journalism practiced today. One of its most famous journalists at the time was Nellie Bly, who was one of the first investigative reporters in the late 1880s. The paper’s headquarters, the New York World Building, shown below, was the tallest office tower in the world when completed in 1890. It was torn down in 1955 to build a new ramp to the Brooklyn Bridge.

The World became one of the first papers to run color in 1896, and its Yellow Kid cartoon lent its name to the term “yellow journalism,” which means sensationalism. The paper earned that sobriquet amid a series of fierce circulation battles with its archrival, the New York Journal American, owned by William Randolph Hearst. Pulitzer was best known for running stories that encouraged the thriving new immigrant community to read his paper, and many had great social impact, particularly its campaign against unsafe tenements. It actively covered the exploits of flashy traders like Livermore, alternately making them out to be folk heroes or villains, depending on editors’ reading of the public mood.

ENDNOTES

1 “Wins $3,000,000 in Six Weeks,”

Chicago Daily Tribune, November 12, 1907, 5.

2 “Hit Market Right,”

Boston Daily Globe, November 12, 1907, 7.

3 Charles Henry Taylor,

History of the Board of Trade of the City of Chicago (1917), 1118.

5 John William Leonard, ed.,

Who’s Who in Finance, Banking, and Insurance (1911), 154.

6 David Greising and Laurie Morse,

Brokers, Bagmen, and Moles (1991), 54.

7 “Who’s Who in Finance,”

Moody’s Magazine (March 1913): 197.

8 Taylor,

History of the Board of Trade of the City of Chicago, 1123.

9 “Grain Corners End,”

New York Times, May 29, 1908, 1.

10 Henry Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street (New York: Irving Publishing Company, 1908), 664.

12 “Death of Armour,”

Time, August 29, 1927.

13 Taylor,

History of the Board of Trade of the City of Chicago, 1125.

14 William B. Dana Company,

The Financial Review (1908), 28-30.

15 “Corn Soars to 79 in the Chicago Pit,”

New York Times, May 20, 1908, 9.

17 Edmund Clarence Stedman,ed.,

The New York Stock Exchange (1908), 308.

18 “Mr. Cammack’s Retirement,”

New York Times, February 7, 1897, 4.

19 “Addison Cammack Dead,”

New York Times, February 6, 1901, 9.

20 Edward G.Riggs, “Wall Street,”

Munsey’s Magazine (1894): 368-370.

21 Edwin Lefevre, “The Unbeatable Game of Stock Speculation,”

Saturday Evening Post, September 4, 1915, 3.

22 “Deacon White Gives It Up,”

New York Times, April 9, 1909, 6.

23 Edwin Griswold Nourse,

Brokerage (1910), 154.

25 Albert William Atwood,

The Exchanges and Speculation (1917), 208.

26 Thomas Ellison,

The Cotton Trade of Great Britain (1886), 166.

27 “Young Broker Raids Cotton,”

Los Angeles Times, August 6, 1908, 11.

28 “The Cotton Market,”

New York Times, April 8, 1908, 8.

29 “Grain Market,”

Boston Daily Globe, May 12, 1908, 7.

31 “Big Jump in July Cotton,”

New York Times, May 14, 1908, 16.

32 “Cotton Up and Down,”

New York Times, May 15, 1908, 16.

33 “Cotton Corner Collapses,”

New York Times, June 24, 1908, 12.

I was short ten million bushels of wheat and ten million bushels of corn. I had studied the grain markets for a long time and was as bearish on corn and wheat as I had been on stocks.

I was short ten million bushels of wheat and ten million bushels of corn. I had studied the grain markets for a long time and was as bearish on corn and wheat as I had been on stocks.

After I cleaned up in stocks and was ready to go South on my yacht I found that wheat showed me a handsome profit, but in corn Stratton had run up the price and I had quite a loss.

After I cleaned up in stocks and was ready to go South on my yacht I found that wheat showed me a handsome profit, but in corn Stratton had run up the price and I had quite a loss. Of course I knew that Stratton would not let me have the corn I needed except at his own price, but the moment I heard the rumors about Armour being against Stratton it occurred to me that I might look to the Chicago traders for aid. The only way in which they could possibly help me was for them to sell me the corn that Stratton wouldn’t. The rest was easy.

Of course I knew that Stratton would not let me have the corn I needed except at his own price, but the moment I heard the rumors about Armour being against Stratton it occurred to me that I might look to the Chicago traders for aid. The only way in which they could possibly help me was for them to sell me the corn that Stratton wouldn’t. The rest was easy.

From all I have heard, I am inclined to think that Cammack was one of the ablest stock traders the Street ever saw. He was not a chronic bear as many believe, but he felt the greater appeal of trading on the bear side, of utilising in his behalf the two great human factors of hope and fear. He is credited with coining the warning: “Don’t sell stocks when the sap is running up the trees!” and the old-timers tell me that his biggest winnings were made on the bull side, so that it is plain he did not play prejudices but conditions. At all events, he was a consummate trader. It seems that once—this was way back at the tag end of a bull market—Cammack was bearish, and J. Arthur Joseph, the financial writer and raconteur, knew it. The market, however, was not only strong but still rising, in response to prodding by the bull leaders and optimistic reports by the newspapers. Knowing what use a trader like Cammack could make of bearish information, Joseph rushed to Cammack’s office one day with glad tidings.

From all I have heard, I am inclined to think that Cammack was one of the ablest stock traders the Street ever saw. He was not a chronic bear as many believe, but he felt the greater appeal of trading on the bear side, of utilising in his behalf the two great human factors of hope and fear. He is credited with coining the warning: “Don’t sell stocks when the sap is running up the trees!” and the old-timers tell me that his biggest winnings were made on the bull side, so that it is plain he did not play prejudices but conditions. At all events, he was a consummate trader. It seems that once—this was way back at the tag end of a bull market—Cammack was bearish, and J. Arthur Joseph, the financial writer and raconteur, knew it. The market, however, was not only strong but still rising, in response to prodding by the bull leaders and optimistic reports by the newspapers. Knowing what use a trader like Cammack could make of bearish information, Joseph rushed to Cammack’s office one day with glad tidings. Joseph expected to hear him give an order to sell at least fifty thousand shares of St. Paul. William Rockefeller was disposing of his holdings in St. Paul, taking advantage of the strength of the market. Whether it was investment stock or speculative holdings was irrelevant. The one important fact was that the best stock trader of the Standard Oil crowd was getting out of St. Paul. What would the average man have done if he had received the news from a trustworthy source? No need to ask.

Joseph expected to hear him give an order to sell at least fifty thousand shares of St. Paul. William Rockefeller was disposing of his holdings in St. Paul, taking advantage of the strength of the market. Whether it was investment stock or speculative holdings was irrelevant. The one important fact was that the best stock trader of the Standard Oil crowd was getting out of St. Paul. What would the average man have done if he had received the news from a trustworthy source? No need to ask.

or enough personal pull to secure the publication of a story like that. It gave me an utterly unearned reputation that time.

or enough personal pull to secure the publication of a story like that. It gave me an utterly unearned reputation that time.