XII

Not long after I closed my July cotton deal more successfully than I had expected I received by mail a request for an interview. The letter was

signed by Percy Thomas. 12.1 Of course I immediately answered that I’d be glad to see him at my office at any time he cared to call. The next day he came.

I had long admired him. His name was a household word wherever men took an interest in growing or buying or selling cotton. In Europe as well as all over this countrypeople quoted Percy Thomas’ opinions to me. I remember once at a Swiss resort talking to a Cairo banker who was interested in cotton growing in Egypt in association with the late Sir Ernest Cassel. 12.2When he heard I was from New York he immediately asked me about Percy Thomas, whose market reports he received and read with unfailing regularity.

12.1 Percy Thomas appears to be a pseudonym for Theodore Hazeltine Price, a southern cotton expert and fi nancier with deep-rooted American lineage. Born in 1861, he was a descendant of John Price, who traveled from Bristol, England, to Virginia in 1720. His grandfather fought in the Revolutionary War, and his father was an early member of the New York Cotton Exchange.

Price got his start in the cotton business in 1882. His skill as a speculator and insights into market conditions were lauded by many: “To a remarkable knowledge of the great staple, he added brilliancy, daring, and an extraordinary grasp of affairs. He wrote well, and his letters to the trade were real contributions to cotton literature,”

1 wrote one admirer. An example was his presentation, at the 1904 convention of the New England Cotton Manufacturers’ Association, on the state the industry. He discussed both America’s rising appetite for cotton and the progress of cotton production and manufacturing in China and India.

2Price was a member of the cotton fi rm Eure, Farrar & Price of Norfolk, Virginia. Later he was head of Price, Reid & Co. in New York City, which eventually merged with a competitor to become Price, McCormick & Company. In 1899 and 1900, Price attempted the largest cotton corner to date, but it failed and bankrupted his fi rm, leaving more than $13 million in liabilities.

3 This is likely the failure Livermore mentions.

Price had good reason to engage in that corner attempt. According to contemporary reports, he was the first man to recognize the crop failure of 1899.

4 In August of that year, prices were low, at around 6 cents per pound. Despite some resistance from the Liverpool market and contrary predictions from London trading houses, Price pushed prices up to 7.5 cents per pound.

Satisfied with his accomplishment, Price started selling the market short early the next year. Prices wavered for a day or two, but soon the crop deficiency became apparent and a journalist reported “the price moved irresistibly upward.”

5 Price quickly switched back to the bull side, but his profits were already lost and he was unable to secure the corner. In following years, cotton prices remained very volatile, allowing Price to conduct profitable trading operations. In the end, he was able to personally repay every dollar his firm’s creditors owed in the bankruptcy.

In his later years, Price focused more heavily on his writing, becoming a commentator on economic and financial matters. He was also editor and owner of the Commerce and Finance, a widely read financial newspaper, where he penned columns on topics including foreign trade with Europe, the effects of World War I, speculation, and credit conditions.

Thomas, I always thought, went about his business scientifically. He was a true speculator, a thinker with the vision of a dreamer and the courage of a fighting man—an unusually well-informed man, who knew both the theory and the practice of trading in cotton. He loved to hear and to express ideas and theories and abstractions, and at the same time there was mighty little about the practical side of the cotton market or the psychology of cotton traders that he did not know, for he had been trading for years and had made and lost vast sums.

12.2

Sir Ernest Cassel was a financier and philanthropist who advised King Edward VII. The New York Times reported in his obituary that the “banker loaned money to nations and had vast enterprises on every continent.”

6 He was born in 1852 in Cologne, Germany, where his father, Jacob, was a banker.

Cassel followed his father’s example. He went to England at 16 to complete his education before working as a clerk for a group of grain

dealers in Liverpool. By 1871, he joined the London banking house of Bischoffsheim & Goldsmid, where he was said to have “displayed his financial genius in straightening out the tangled affairs of one of the largest firms in the city.”

7 At the time, Bischoffsheim was actively involved in the building of British railroads, a business in which lawsuits were often unavoidable.

8 Cassel’s tough negotiating—“even lawyers feared him,”

9 said a royal biographer—secured favorable settlements and kept his firm out of court.

Eventually, Cassel founded his own firm and focused on extending his reach to distant corners of the globe. Upon his retirement at the age of 58, he had accumulated one of the largest fortunes in England. One of his first achievements in international finance was to come to the aid of Argentina in 1890 when its finances collapsed.

This was followed by transactions in Mexico, Sweden, Egypt, and the United States. He helped direct a loan to China after its first war with Japan. His knighthood, bestowed by Queen Victoria, was in response to his work in financing the Aswan Dam in Egypt. Over the opposition of France and Turkey, Cassel secured an agreement from the Egyptian government to allow British firms to dam the Nile River. He also assisted in the creation of the National Bank of Egypt and the Agricultural Bank of Egypt.

10Contemporary accounts describe Cassel as reserved and cool. He rarely shared his feelings with others. But he certainly had a deep concern for his fellow man, as according to a biographer, “London institutions received more than a million pounds from his bounty, cancer research, hospitals, and education coming in for his especial benevolence.”

11After the failure of his old Stock Exchange firm of Sheldon & Thomas he went it alone. Inside of two years he came back, almost spectacularly. I remember reading in the Sun that the first thing he did when he got on his feet financially was to pay off his old creditors in full, and the next was to hire an expert to study and determine for him how he had best invest a million dollars. This expert examined the properties and analysed the reports of several companies and then recommended the purchase of Delaware & Hudson stock. 12.3

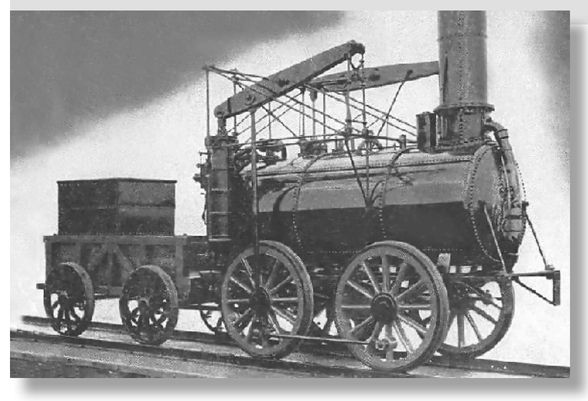

12.3 The Delaware & Hudson was originally chartered in 1823 to build canals between New York City and the coal fields of eastern Pennsylvania. The company was one of the earliest adopters of rail technology in the United States. When it was decided that a particular 16-mile section was too mountainous for a canal, Delaware & Hudson built a railway instead. On it the Stourbridge Lion, the first steam locomotive to operate in North America, was tested.

12 (The locomotive, named for the town in England where it was built, never actually ran commercially on the D&H track because the rails were built for machines weighing four tons or less, and it weighed in at 7.5 tons. A replica of the Lion is shown below.) During Livermore’s time, the company had expanded to become an important bridge railroad that provided other railroad systems with a connection between New York and Montreal, Canada.

Well, after having failed for millions and having come back with more millions, Thomas was cleaned out as the result of his deal in March cotton. There wasn’t much time wasted after he came to see me. He proposed that we form a working alliance. Whatever information he got he would immediately turn over to me before passing it on to the public. My part would be to do the actual trading, for which he said I had a special genius and he hadn’t.

That did not appeal to me for a number of reasons. I told him frankly that I did not think I could run in double harness and wasn’t keen about trying to learn. But he insisted that it would be an ideal combination until I said flatly that I did not want to have anything to do with influencing other people to trade.

“If I fool myself,” I told him, “I alone suffer and I pay the bill at once. There are no drawn-out payments or unexpected annoyances. I play a lone hand by choice and also because it is the wisest and cheapest way to trade. I get my pleasure out of matching my brains against the brains of other traders—men whom I have never seen and never talked to and never advised to buy or sell and never expect to meet or know. When I make money I make it backing my own opinions. I don’t sell them or capitalise them. If I made money in any other way I would imagine I had not earned it. Your proposition does not interest me because I am interested in the game only as I play it for myself and in my own way.”

He said he was sorry I felt the way I did, and tried to convince me that I was wrong in rejecting his plan. But I stuck to my views. The rest was a pleasant talk. I told him I knew he would “come back” and that I would consider it a privilege if he would allow me to be of financial assistance to him. But he said he could not accept any loans from me. Then he asked me about my July deal and I told him all about it; how I had gone into it and how much cotton I bought and the price and other details. We chatted a little more and then he went away.

When I said to you some time ago that a speculator has a host of enemies, many of whom successfully bore from within, I had in mind my many mistakes. I have learned that a man may possess an original mind and a lifelong habit of independent thinking and withal be vulnerable to attacks by a persuasive personality. I am fairly immune from the commoner speculative ailments, such as greed and fear and hope. But being an ordinary man I find I can err with great ease.

I ought to have been on my guard at this particular time because not long before that I had had an experience that proved how easily a man may be talked into doing something against his judgment and even against his wishes. It happened in Harding’s office. I had a sort of private office—a room that they let me occupy by myself—and nobody was supposed to get to me during market hours without my consent. I didn’t wish to be bothered and, as I was trading on a very large scale and my account was fairly profitable, I was pretty well guarded.

One day just after the market closed I heard somebody say, “Good afternoon, Mr. Livingston.”

I turned and saw an utter stranger—a chap of about thirty or thirty-five. I could not understand how he’d got in, but there he was. I concluded his business with me had passed him. But I didn’t say anything. I just looked at him and pretty soon he said, “I came to see you about that Walter Scott,” and he was off. 12.4

12.4 Sir Walter Scott was a Scottish novelist and poet who lived from 1771 to 1832. His works include Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, and the Waverley novels. The latter was a series of books that were very popular in Europe throughout the 1800s. Scott’s works were heavily influenced by Enlightenment thinking. Tolerance and classlessness were featured prominently. Scott famously penned the line “Oh! What a tangled web we weave, When first we practise to deceive!” as part of the poem Marmion.

He was a book agent. Now, he was not particularly pleasing of manner or skillful of speech. Neither was he especially attractive to look at. But he certainly had personality. He talked and I thought I listened. But I do not know what he said. I don’t think I ever knew, not even at the time. When he finished his monologue he handed me first his fountain pen and then a blank form, which I signed. It was a contract to take a set of Scott’s works for five hundred dollars.

The moment I signed I came to. But he had the contract safe in his pocket. I did not want the books. I had no place for them. They weren’t of any use whatever to me. I had nobody to give them to. Yet I had agreed to buy them for five hundred dollars.

I am so accustomed to losing money that I never think first of that phase of my mistakes. It is always the play itself, the reason why. In the first place I wish to know my own limitations and habits of thought. Another reason is that I do not wish to make the same mistake a second time. A man can excuse his mistakes only by capitalising them to his subsequent profit.

Well, having made a five-hundred dollar mistake but not yet having localised the trouble, I just looked at the fellow to size him up as a first step. I’ll be hanged if he didn’t actually smile at me—an understanding little smile! He seemed to read my thoughts. I somehow knew that I did not have to explain anything to him; he knew it without my telling him. So I skipped the explanations and the preliminaries and asked him, “How much commission will you get on that five hundred dollar order?”

He promptly shook his head and said, “I can’t do it! Sorry!”

“How much do you get?” I persisted.

“A third. But I can’t do it!” he said.

“A third of five hundred dollars is one hundred and sixty-six dollars and sixty-six cents. I’ll give you two hundred dollars cash if you give me back that signed contract.” And to prove it I took the money out of my pocket.

“I told you I couldn’t do it,” he said.

“Do all your customers make the same offer to you?” I asked.

“No,” he answered.

“Then why were you so sure that I was going to make it?”

“It is what your type of sport would do. You are a first-class loser and that makes you a first-class business man. I am much obliged to you, but I can’t do it.”

“Now tell me why you do not wish to make more than your commission?”

“It isn’t that, exactly,” he said. “I am not working just for the commission.”

“What are you working for then?”

“For the commission and the record,” he answered.

“What record?”

“Mine.”

“What are you driving at?”

“Do you work for money alone?” he asked me.

“Yes,” I said.

“No.” And he shook his head. “No, you don’t. You wouldn’t get enough fun out of it. You certainly do not work merely to add a few more dollars to your bank account and you are not in Wall Street because you like easy money. You get your fun some other way. Well, same here.”

12.5 Although it may seem strange that a traveling salesman would show up in a brokerage office to hawk a set of Sir Walter Scott books, this was not an unfamiliar phenomenon at the time.

Itinerant peddlers were common in the United States as early as the pre-Revolutionary War era, but the concept of salesmen working on commission for a large company really only developed in the post-Civil War era. Called “canvassers” or “drummers,” traveling salesmen depended on their wits and shrewd insights into human nature at first. But by the 1860s, companies were marking out sales territories, setting commission rates, and developing scripts to help their men wrestle their wares past the objections of lonely, fretful, and poor farmers and shopkeepers.

Traveling sellers of book subscriptions, sets or volumes, who were called “agents,” received elaborate instruction kits on how to talk to prospects that soon leveraged a canon of rules and tips that would be recognizable today for its emphasis on persuasion rather than content.

13 Religious, self-help and history books were common, as customers worried about their souls and status.

The fi rst important book sold by agents was Birds of America, written and illustrated by John James Audubon in the 1820s. Fifty years later, Mark Twain used subscriptions exclusively to sell his fi rst books, including Innocents Abroad in 1869 and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer in 1876, and got heavily involved in the marketing campaigns—right down to writing out proposed patter.

14 And in the 1880s, Twain persuaded Ulysses S. Grant to let his sales force take on the task of hawking the dying ex-president’s memoirs door to door around the country. A pamphlet titled, “How to Introduce the Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant” outlined sales arguments. Grant’s fortune had been nearly wiped out in a Wall Street swindle in 1884, so salesmen used sympathy for his impoverishment as a tactic to persuade veterans to buy the book. The Twain campaign was ultimately a tremendous success, netting Grant’s family at least $450,000—around $8 million today.

15Many titans of twentieth-century sales got their starts as door-to-door book agents, including David Hall McConnell, who went on to start the California Perfume Co., and later transformed that into Avon Products, the industry standard.

16 Other early-century entrepreneurs and inventors who also went door to door to sell their ideas were future chewing gum magnate William Wrigley Jr., cereal titan C. W. Post, adding machine pioneer William S. Burroughs, and ketchup king Henry Heinz.

17So the insightful salesman of Scott books with whom Livermore tangled was part of a rich tradition in the era before marketers could use radio and television to market on a much broader scale. (Ad seeking traveling book salesmen, at left, appeared in Publishers Weekly in 1910.)

I did not argue but asked him, “And how do you get your fun?”

“Well,” he confessed, “we’ve all got a weak spot.”

“And what’s yours?”

“Vanity,” he said.

“Well,” I told him, “you succeeded in getting me to sign on. Now I want to sign off, and I am paying you two hundred dollars for ten minutes’ work. Isn’t that enough for your pride?”

“No,” he answered. “You see, all the rest of the bunch have been working Wall Street for months and failed to make expenses. They said it was the fault of the goods and the territory. So the office sent for me to prove that the fault was with their salesmanship and not with the books or the place. They were working on a 25 per cent commission. I was in Cleveland, where I sold eighty-two sets in two weeks. I am here to sell a certain number of sets not only to people who did not buy from the other agents but to people they couldn’t even

get to see. That’s why they give me 331/3 per cent.”

“I can’t quite figure out how you sold me that set.”

“Why,” he said consolingly, “I sold J. P. Morgan a set.”

“No, you didn’t,” I said.

He wasn’t angry. He simply said, “Honest, I did!”

“A set of Walter Scott to J. P. Morgan, who not only has some fine editions but probably the original manuscripts of some of the novels as well?”

“Well, here’s his John Hancock.” And he promptly flashed on me a contract signed by J. P. Morgan himself. It might not have been Mr. Morgan’s signature, but it did not occur to me to doubt it at the time. Didn’t he have mine in his pocket? All I felt was curiosity. So I asked him, “How did you get past the librarian?”

“I didn’t see any librarian. I saw the Old Man himself. In his office.”

“That’s too much!” I said. Everybody knew that it was much harder to get into Mr. Morgan’s private office empty handed than into the White House with a parcel that ticked like an alarm clock.

But he declared, “I did.”

“But how did you get into his office?”

“How did I get into yours?” he retorted.

“I don’t know. You tell me,” I said.

“Well, the way I got into Morgan’s office and the way I got into yours are the same. I just talked to the fellow at the door whose business it was not to let me in. And the way I got Morgan to sign was the same way I got you to sign. You weren’t signing a contract for a set of books. You just took the fountain pen I gave you and did what I asked you to do with it. No difference. Same as you.”

“And is that really Morgan’s signature?” I asked him, about three minutes late with my skepticism.

“Sure! He learned how to write his name when he was a boy.”

“And that’s all there’s to it?”

“That’s all,” he answered. “I know exactly what I am doing. That’s all the secret there is. I am much obliged to you. Good day, Mr. Livingston.” And he started to go out.

“Hold on,” I said. “I’m bound to have you make an even two hundred dollars out of me.” And I handed him thirty-five dollars.

He shook his head. Then: “No,” he said. “I can’t do that. But I can do this!” And he took the contract from his pocket, tore it in two and gave me the pieces.

I counted two hundred dollars and held the money before him, but he again shook his head.

“Isn’t that what you meant?” I said.

“No.”

“Then, why did you tear up the contract?”

“Because you did not whine, but took it as I would have taken it myself had I been in your place.”

“But I offered you the two hundred dollars of my own accord,” I said.

“I know; but money isn’t everything.”

Something in his voice made me say, “You’re right; it isn’t. And now what do you really want me to do for you?”

“You’re quick, aren’t you?” he said. “Do you really want to do something for me?”

“Yes,” I told him, “I do. But whether I will or not depends what it is you have in mind.”

“Take me with you into Mr. Ed Harding’s office and tell him to let me talk to him three minutes by the clock. Then leave me alone with him.”

I shook my head and said, “He is a good friend of mine.”

“He’s fifty years old and a stock broker,” said the book agent.

That was perfectly true, so I took him into Ed’s office. I did not hear anything more from or about that book agent. But one evening some weeks later when I was going uptown I ran across him in a Sixth Avenue L train. He raised his hat very politely and I nodded back. He came over and asked me, “How do you do, Mr. Livingston? And how is Mr. Harding?”

“He’s well. Why do you ask?” I felt he was holding back a story.

“I sold him two thousand dollars’ worth of books that day you took me in to see him.”

“He never said a word to me about it,” I said.

“No; that kind doesn’t talk about it.”

“What kind doesn’t talk?”

“The kind that never makes mistakes on account of its being bad business to make them. That kind always knows what he wants and nobody can tell him different. That is the kind that’s educating my children and keeps my wife in good humor. You did me a good turn, Mr. Livingston. I expected it when I gave up the two hundred dollars you were so anxious to present to me.”

“And if Mr. Harding hadn’t given you an order?”

“Oh, but I knew he would. I had found out what kind of man he was. He was a cinch.”

“Yes. But if he hadn’t bought any books?” I persisted.

“I’d have come back to you and sold you something. Good day, Mr. Livingston. I am going to see the mayor.” And he got up as we pulled up at Park Place.

“I hope you sell him ten sets,” I said. His Honor was a Tammany man. 12.6

“I’m a Republican, too,” he said, and went out, not hastily, but leisurely, confident that the train would wait. And it did.

I have told you this story in such detail because it concerned a remarkable man who made me buy what I did not wish to buy. He was the first man who did that to me. There never should have been a second, but there was. You can never bank on there being but one remarkable salesman in the world or on complete immunization from the influence of personality.

12.6 Tammany Hall was a Democratic Party political machine that played a role in New York City politics from the late 1700s through the 1960s. Founded in 1789 as the Tammany Society, originally envisaged as a fraternal organization, the group became increasingly politicized under Aaron Burr.

18 In Livermore’s time, the organization was synonymous with the corruption of New York politics under William “Boss” Tweed in the mid-1800s. Tweed was in league with speculators Jim Fisk and Jay Gould and helped arrange favorable legislation for them.

At the time Livermore’s story likely takes place, in 1907 or 1908, the mayor of New York was George Brinton McClellan Jr. Although McClellan was a Democrat affiliated with Tammany Hall, he actually battled the organization upon reelection in 1905 after promising an independent administration during the campaign.

19When Percy Thomas left my office, after I had pleasantly but definitely declined to enter into a working alliance with him, I would have sworn that our business paths would never cross. I was not sure I’d ever even see him again. But on the very next day he wrote me a letter thanking me for my offers of help and inviting me to come and see him. I answered that I would. He wrote again. I called.

I got to see a great deal of him. It was always a pleasure for me to listen to him, he knew so much and he expressed his knowledge so interestingly. I think he is the most magnetic man I ever met.

We talked of many things, for he is a widely read man with an amazing grasp of many subjects and a remarkable gift for interesting generalization. The wisdom of his speech is impressive; and as for plausibility, he hasn’t an equal. I have heard many people accuse Percy Thomas of many things, including insincerity, but I sometimes wonder if his remarkable plausibility does not come from the fact that he first convinces himself so thoroughly as to acquire thereby a greatly increased power to convince others.

Of course we talked about market matters at great length. I was not bullish on cotton, but he was. I could not see the bull side at all, but he did. He brought up so many facts and figures that I ought to have been overwhelmed, but I wasn’t. I couldn’t disprove them because I could not deny their authenticity, but they did not shake my belief in what I read for myself. But he kept at it until I no longer felt sure of my own information as gathered from the trade papers and the dailies. That meant I couldn’t see the market with my own eyes. A man cannot be convinced against his own convictions, but he can be talked into a state of uncertainty and indecision, which is even worse, for that means that he cannot trade with confidence and comfort.

I cannot say that I got all mixed up, exactly, but I lost my poise; or rather, I ceased to do my own thinking. I cannot give you in detail the various steps by which I reached the state of mind that was to prove so costly to me. I think it was his assurances of the accuracy of his figures, which were exclusively his, and the undependability of mine, which were not exclusively mine, but public property. He harped on the utter reliability, as proved time and again, of all his ten thousand correspondents throughout the South. In the end I came to read conditions as he himself read them—because we were both reading from the same page of the same book, held by him before my eyes. He has a logical mind. Once I accepted his facts it was a cinch that my own conclusions, derived from his facts, would agree with his own.

When he began his talks with me about the cotton situation I not only was bearish but I was short of the market. Gradually, as I began to accept his facts and figures, I began to fear I had been basing my previous position on misinformation. Of course I could not feel that way and not cover. And once I had covered because Thomas made me think I was wrong, I simply had to go long. It is the way my mind works. You know, I have done nothing in my life but trade in stocks and commodities. I naturally think that if it is wrong to be bearish it must be right to be a bull. And if it is right to be a bull it is imperative to buy. As my old Palm Beach friend said Pat Hearne used to say, “You can’t tell till you bet!” I must prove whether I am right on the market or not; and the proofs are to be read only in my brokers’ statements at the end of the month.

I started in to buy cotton and in a jiffy I had my usual line, about sixty thousand bales. It was the most asinine play of my career. Instead of standing or falling by my own observation and deductions I was merely playing another man’s game. It was eminently fitting that my silly plays should not end with that. I not only bought when I had no business to be bullish but I didn’t accumulate my line in accordance with the promptings of experience. I wasn’t trading right. Having listened, I was lost.

12.7 Given Livermore’s preference for staying close to Wall Street when he has a large position out, his likely destination was the Raritan Bayshore region of New Jersey. The shoreline of Sandy Hook, which is the barrier spit that separates Lower New York Bay from the Atlantic Ocean, would have been a good spot for him to walk by the water and collect his thoughts.

12.8 Initially, it appeared as if Livermore was about to strike gold again. On August 6, the Los Angeles Times reported: “The entire supply of cotton stored in New York City and vicinity…has been cornered by J.L. Livermore, the young broker, who last May made more than $2,000,000 in a corner on the July options.”

20 The price had advanced by $3.50 a bale over the previous two weeks as the short sellers became more concerned about the tenability of their positions. Said the Times: “An enormous quantity of October contracts have been sold short in New York because of the general belief…that an enormous croup will be gathered.”

21The Chicago Daily Tribune also covered the story through its local bureau:

A fair haired, beardless man of 31, younger looking by ten years than his age, who sits in a back room of a brokerage house and issues orders to a score of busy clerks in a gently modulated voice, has possessed himself of every bale of cotton not under contract in the warehouses of Greater New York, and is smilingly watching the painful contortions of a group of grizzled bears on the New York cotton exchange.

22Soon it was apparent something went terribly wrong for the Boy Plunger. On August 13, the New York Times reported that the “bull interests in the cotton market, who have had to fi ght to maintain their position in the market within the last few days, were forced to meet a still heavier onset of the bears yesterday,” which knocked prices down $4.25 a bale below the highs reached the previous week.

23 Ominously, most of the selling was done by an “operator, who has been supposed to be in harmony with the bull leader.”

24On August 20, the market broke badly, sending cotton down $5 per bale compared to the previous week as members of the bull pool were credited with selling some 75,000 bales just within the fi rst hour of trading. The day before, Theodore Price sent out a market letter that seemed to confi rm the rumor that he was an active member of the bull party. A reporter asked Livermore about the heavy losses being credited to him. “I keep my own books,” he said in response. “I am not publishing them to the Street.”

25The market was not going my way. I am never afraid or impatient when I am sure of my position. But the market didn’t act the way it should have acted had Thomas been right. Having taken the first wrong step I took the second and the third, and of course it muddled me all up. I allowed myself to be persuaded not only into not taking my loss but into holding up the market. That is a style of play foreign to my nature and contrary to my trading principles and theories. Even as a boy in the bucket shops I had known better. But I was not myself. I was another man—a Thomasized person.

I not only was long of cotton but I was carrying a heavy line of wheat. That was doing famously and showed me a handsome profit. My fool efforts to bolster up cotton had increased my line to about one hundred and fifty thousand bales. I may tell you that about this time I was not feeling very well. I don’t say this to furnish an excuse for my blunders, but merely to state a pertinent fact. I remember I went to Bayshore for a rest.

While there I did some thinking. It seemed to me that my speculative commitments were over-large. I am not timid as a rule, but I got to feeling nervous and that made me decide to lighten my load. To do this I must clean up either the cotton or the wheat.

It seems incredible that knowing the game as well as I did and with an experience of twelve or fourteen years of speculating in stocks and commodities I did precisely the wrong thing. The cotton showed me a loss and I kept it. The wheat showed me a profit and I sold it out. It was an utterly foolish play, but all I can say in extenuation is that it wasn’t really my deal, but Thomas’. Of all speculative blunders there are few greater than trying to average a losing game. My cotton deal proved it to the hilt a little later. Always sell what shows you a loss and keep what shows you a profit. That was so obviously the wise thing to do and was so well known to me that even now I marvel at myself for doing the reverse.

And so I sold my wheat, deliberately cut short my profit in it. After I got out of it the price went up twenty cents a bushel without stopping. If I had kept it I might have taken a profit of about eight million dollars. And having decided to keep on with the losing proposition I bought more cotton!

I remember very clearly how every day I would buy cotton, more cotton. And why do you think I bought it? To keep the price from going down! If that isn’t a supersucker play, what is? I simply kept on putting up more and more money—more money to lose eventually. My brokers and my intimate friends could not understand it; and they don’t to this day. Of course if the deal had turned out differently I would have been a wonder. More than once I was warned against placing too much reliance on Percy Thomas’ brilliant analyses. To this I paid no heed, but kept on buying cotton to keep it from going down. I was even buying it in Liverpool. I accumulated four hundred and forty thousand bales before I realised what I was doing. And then it was too late. So I sold out my line.

I lost nearly all that I had made out of all my other deals in stocks and commodities. I was not completely cleaned out, but I had left fewer hundreds of thousands than I had millions before I met my brilliant friend Percy Thomas.

For me of all men to violate all the laws that experience had taught me to observe in order to prosper was more than asinine.

Price had double-crossed Livermore by participating in the rise before switching to the short side and trapping the trader as he was forced to close his large position. A Boston newspaper reported: “It is known that Theodore H. Price, who was in the original deal with Mr. Livermore, has been bearish for more than a week. Mr. Price is supposed to have been short of the market on the slump, and to have made a handsome profi t on the decline. Mr. Price is reputed to have sold out all of his long cotton in the recent rise.”

26Livermore had overreached. He was betting on a pledge from the cotton farmers’ union to not sell cotton for less than 10 cents a pound. But when push came to shove as an abundant crop threatened their livelihood, the union ignored the price floor and quickly took the best available offer. Livermore, said the paper, had been “opposed by a score of old operators on the exchange, who have had much longer experience. … They knew the temperament of the southern planter better than their young adversary.”

27Livermore quickly bounced back. By October, he reportedly cleared $500,000 as a result of increases in his equity positions in Union Pacific, Southern Pacific, and Reading and St. Paul railroads. It was said at the time that his operations in the stock and cotton markets were reportedly “heavier than those of any other speculator.”

2812.9 A woodbine is a climbing vine much like a honey-suckle, with yellow flowers. “Twineth” is an old-fashioned version of the verb “twine,” meaning to become twisted or entangled.

According to a biography of James Fisk Jr., this strange locution has its origins in the congressional investigation of the Black Friday panic. When asked later what he meant by this phrase, which had become a part of the financier’s legend, he explained that he had used it as a euphemism: “You see I was before that learned and dignified body, the Committee on Banking and Currency, and when Garfield asked me where the money got by Corbin went to, I could not make a vulgar reply, and say ‘up a spout,’ but observing, while peddling through New England, that every spout of house or cottage had a woodbine twining about it, I said, naturally enough, ‘where the woodbine twineth.’”

His biographer then added: “His famous reply when asked where the money had gone—‘Gone where the woodbine twineth’—will be remembered as long as the memorable panic itself will.”

29So why was “up the spout” considered vulgar? The New York Times in 1871 wasn’t quite sure, so on September 3 it published a 1,115 word essay on what editors called “that remarkable sentence.”

30 The paper concluded that Fisk didn’t realize the term came from England and meant an item had been pawned, apparently because of the spout-like device pawnbrokers used to send new items into storage.

But there was another definition that the prim Times editors may not have known about. Dictionaries of 19th Century slang report that it was used to describe the condition of a young, unmarried woman who had become pregnant, and thus “ruined.”

31 This may well have been the meaning the bawdy trader had in mind.

12.10 Livermore needed to raise this cash to defend his brother-in-law, vaudeville performer Chester S. Jordan, after he was accused of murdering his wife.

32 Jordan was eventually sentenced to death for his crime despite an appeal to the United States Supreme Court on the grounds that one of his jurors went insane as a result of the trial.

33To learn that a man can make foolish plays for no reason whatever was a valuable lesson. It cost me millions to learn that another dangerous enemy to a trader is his susceptibility to the urgings of a magnetic personality when plausibly expressed by a brilliant mind. It has always seemed to me, however, that I might have learned my lesson quite as well if the cost had been only one million. But Fate does not always let you fix the tuition fee. She delivers the educational wallop and presents her own bill, knowing you have to pay it, no matter what the amount may be. Having learned what folly I was capable of I closed that particular incident. Percy Thomas went out of my life.

There I was, with more than nine-tenths of my stake, as Jim Fisk used to say, gone where the woodbine twineth—up the spout. 2.9 I had been a millionaire rather less than a year. My millions I had made by using brains, helped by luck. I had lost them by reversing the process. I sold my two yachts and was decidedly less extravagant in my manner of living.

But that one blow wasn’t enough. Luck was against me. I ran up first against illness and then against the urgent need of two hundred thousand dollars in cash. 2.10 A few months before that sum would have been nothing at all; but now it meant almost the entire remnant of my fleet-winged fortune. I had to supply the money and the question was: Where could I get it? I didn’t want to take it out of the balance I kept at my brokers’ because if I did I wouldn’t have much of a margin left for my own trading; and I needed trading facilities more than ever if I was to win back my millions quickly. There was only one alternative that I could see, and that was to take it out of the stock market!

Just think of it! If you know much about the average customer of the average commission house you will agree with me that the hope of making the stock market pay your bill is one of the most prolific sources of loss in Wall Street. You will chip out all you have if you adhere to your determination.

Why, in Harding’s office one winter a little bunch of high flyers spent thirty or forty thousand dollars for an overcoat—and not one of them lived to wear it. It so happened that a prominent floor trader—who since has become world-famous as one of the dollar-a-year men—came down to the Exchange wearing a fur overcoat lined with sea otter.

In those days, before furs went up sky high, that coat was valued at only ten thousand dollars. Well, one of the chaps in Harding’s office, Bob Keown, decided to get a coat lined with Russian sable. He priced one uptown. The cost was about the same, ten thousand dollars.

“That’s the devil of a lot of money,” objected one of the fellows.

“Oh, fair! Fair!” admitted Bob Keown amiably. “About a week’s wages—unless you guys promise to present it to me as a slight but sincere token of the esteem in which you hold the nicest man in the office. Do I hear the presentation speech? No? Very well. I shall let the stock market buy it for me!”

“Why do you want a sable coat?” asked Ed Harding.

“It would look particularly well on a man of my inches,” replied Bob, drawing himself up.

“And how did you say you were going to pay for it?” asked Jim Murphy, who was the star tip-chaser of the office.

“By a judicious investment of a temporary character, James. That’s how,” answered Bob, who knew that Murphy merely wanted a tip.

Sure enough, Jimmy asked, “What stock are you going to buy?”

“Wrong as usual, friend. This is no time to buy anything. I propose to sell five thousand Steel. It ought to go down ten points at the least. I’ll just take two and a half points net. That is conservative, isn’t it?”

2.11 Dollar-a-year men were business executives who were inspired by the moral righteousness of America’s role in World War I to enter government service in their areas of expertise. Because U.S. law forbade the government from accepting free services, they accepted $1 a year for their work, plus expenses.

The term was later used again in World War II, and was used to distinguish high-level businessmen who came to work for the government in difficult jobs like materiel procurement from middle managers who needed a real wage while serving as reservists in disciplines like logistics. Dollar-a-year men were often accused of favoring their old business loyalties when private and public interests came into conflict, such as when ordering a new blast furnace to make steel for arms might take resources away from commercial interests.

“What do you hear about it?” asked Murphy eagerly. He was a tall thin man with black hair and a hungry look, due to his never going out to lunch for fear of missing something on the tape.

“I hear that coat’s the most becoming I ever planned to get.” He turned to Harding and said, “Ed, sell five thousand U.S. Steel common at the market. To-day, darling!”

He was a plunger, Bob was, and liked to indulge in humorous talk. It was his way of letting the world know that he had an iron nerve. He sold five thousand Steel, and the stock promptly went up. Not being half as big an ass as he seemed when he talked, Bob stopped his loss at one and a half points and confided to the office that the New York climate was too benign for fur coats. They were unhealthy and ostentatious. The rest of the fellows jeered. But it was not long before one of them bought some Union Pacific to pay for the coat. He lost eighteen hundred dollars and said sables were all right for the outside of a woman’s wrap, but not for the inside of a garment intended to be worn by a modest and intelligent man.

After that, one after another of the fellows tried to coax the market to pay for that coat. One day I said I would buy it to keep the office from going broke. But they all said that it wasn’t a sporting thing to do; that if I wanted the coat for myself I ought to let the market give it to me. But Ed Harding strongly approved of my intention and that same afternoon I went to the furrier’s to buy it. I found out that a man from Chicago had bought it the week before.

That was only one case. There isn’t a man in Wall Street who has not lost money trying to make the market pay for an automobile or a bracelet or a motor boat or a painting. I could build a huge hospital with the birthday presents that the tight-fisted stock market has refused to pay for. In fact, of all oodoos in Wall Street 2.12 I think the resolve to induce the stock market to act as a fairy godmother is the busiest and most persistent.

Like all well-authenticated hoodoos this has its reason for being. What does a man do when he sets out to make the stock market pay for a sudden need? Why, he merely hopes. He gambles. He therefore runs much greater risks than he would if he were speculating intelligently, in accordance with opinions or beliefs logically arrived at after a dispassionate study of underlying conditions. To begin with, he is after an immediate profit. He cannot afford to wait. The market must be nice to him at once if at all. He flatters himself that he is not asking more than to place an even-money bet. Because he is prepared to run quick—say, stop his loss at two points when all he hopes to make is two points—he hugs the fallacy that he is merely taking a fifty-fifty chance. Why, I’ve known men to lose thousands of dollars on such trades, particularly on purchases made at the height of a bull market just before a moderate reaction. It certainly is no way to trade.

Well, that crowning folly of my career as a stock operator was the last straw. It beat me. I lost what little my cotton deal had left me. It did even more harm, for I kept on trading—and losing. I persisted in thinking that the stock market must perforce make money for me in the end. But the only end in sight was the end of my resources. I went into debt, not only to my principal brokers but to other houses that accepted business from me without my putting up an adequate margin. I not only got in debt but I stayed in debt from then on.

2.12 Hoodoo is a form of folk magic that developed in the southern United States in the 1800s as a blend of African, Native American, and Christian cultures. It was originally used to described a magic spell, but also was used to describe a conjurer or witch, or objects that hoodoo practitioners created to cast a spell. The term could also refer to itinerant healers who traveled the countryside in the 1800s dispensing folk remedies, charms, and herbal potions aimed at helping people enlist supernatural forces for help with luck, money or love.

34

Hoodoos used anything at hand to create their spells, including, according to one account, chicken feathers, earthworms, red peppers, coffee grounds, nails, beef tongues, oils, powders and graveyard dirt.

35 A hoodoo named Julia Jackson was said to have devised this formula to kill someone: “Catch a rattlesnake, kill it, hang it in the sun to dry. Write the person’s name on a piece of paper and put it in the snake’s mouth. Just like that snake dry up the person gonna dry up too. If you keep that snake in the sun long enough the person’s gonna die.”

36Traders have long used the term sardonically to mean paranormal beings or enchantments that prevent them from enjoying success. Livermore had a lot of personal superstitions, and one of the most closely held was that traders should not expect the market to deliver the money to pay for a specific expensive item, like a car or a fur coat. He believed that the notion cursed traders’ thought processes, making them short-term oriented and wishful when they should be analytical.

ENDNOTES

1 Isaac F. Marcosson, “The Perilous Game of Cornering a Crop,”

Munsey’s Magazine (November 1910): 239.

2 “Cotton Manufacturers’ Conventions,”

Dun’s Review (March 1904): 48.

3 The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography (1910), 281.

4 Marcosson, “Perilous Game of Cornering a Crop.”

6 “Sir Ernest Cassel Dead in London,”

New York Times, September 23, 1921, 12.

8 Sidney Lee,

King Edward VII: A Biography Part II (1927), 60.

10 “Foreign Banking and Finance,”

Banker’s Magazine (1911): 392.

12 John H. White,

A History of the American Locomotive (1979), 239.

13 Birth of a Salesman: The transformation of selling in America. Walter A. Friedman. Harvard University Press. 2004. 36.

18 Gustavus Myers,

The History of Tammany Hall (1917), 13.

20 “Young Broker Raids Cotton,”

Los Angeles Times, August 6, 1908, 11.

22 “Corner in Cotton by a Lamb of 31,”

Chicago Daily Tribune, August 10, 1908, 9.

23 “Bears Raid Cotton and Smash Prices,”

New York Times, August 13, 1908, 8.

25 “Bull Pool in Cotton Smashed by Bears,”

New York Times, August 21, 1908, 14.

26 “Cotton Bulls in Big Panic,”

Boston Daily Globe, August 21, 1908, 11.

28 “$500,000 to the Good,”

Boston Daily Globe, October 31, 1908, 9.

29 Edward L. Stokes,

The Life of Col. James Fisk Jr. (H.S. Goodspeed & Co., 1872), 69.

30 “Up the Spout,”

New York Times, p. 5, September 3, 1871.

31 The Routledge Dictionary of Historical Slang. Eric Partridge and Jacqueline Simpson. 1973. 894

32 “Wife Slayer Aided by Cotton Plunger,”

New York Times, September 5, 1908, 2.

33 “Question Murder Juror’s Sanity,”

New York Times, February 1, 1911, 7.

34 Herbal Magick: A Witch’s Guide to Herbal Folklore and Enhantments. Gerina Dunwich. Career Press. 2002.

35 Joseph E. Holloway, Africanisms in American Culture. (Indiana University Press), 144.

signed by Percy Thomas. 12.1 Of course I immediately answered that I’d be glad to see him at my office at any time he cared to call. The next day he came.

signed by Percy Thomas. 12.1 Of course I immediately answered that I’d be glad to see him at my office at any time he cared to call. The next day he came. signed by Percy Thomas. 12.1 Of course I immediately answered that I’d be glad to see him at my office at any time he cared to call. The next day he came.

signed by Percy Thomas. 12.1 Of course I immediately answered that I’d be glad to see him at my office at any time he cared to call. The next day he came.

For me of all men to violate all the laws that experience had taught me to observe in order to prosper was more than asinine.

For me of all men to violate all the laws that experience had taught me to observe in order to prosper was more than asinine. In those days, before furs went up sky high, that coat was valued at only ten thousand dollars. Well, one of the chaps in Harding’s office, Bob Keown, decided to get a coat lined with Russian sable. He priced one uptown. The cost was about the same, ten thousand dollars.

In those days, before furs went up sky high, that coat was valued at only ten thousand dollars. Well, one of the chaps in Harding’s office, Bob Keown, decided to get a coat lined with Russian sable. He priced one uptown. The cost was about the same, ten thousand dollars.