XIV

It has always rankled in my mind that after I left Williamson & Brown’s office the cream was off the market. We ran smack into a long moneyless period; four mighty lean years. There was not a penny to be made. As Billy Henriquez once said, “It was the kind of market in which not even a skunk could make a scent.”

It looked to me as though I was in Dutch with destiny. It might have been the plan of Providence to chasten me, but really I had not been filled with such pride as called for a fall. I had not committed any of those speculative sins which a trader must expiate on the debtor side of the account. I was not guilty of a typical sucker play. What I had done, or, rather, what I had left undone, was something for which I would have received praise and not blame—north of Forty-second Street. In Wall Street it was absurd and costly. But by far the worst thing about it was the tendency it had to make a man a little less inclined to permit himself human feelings in the ticker district.

I left Williamson’s and tried other brokers’ offices. In every one of them I lost money. It served me right, because I was trying to force the market into giving me what it didn’t have to give—to wit, opportunities for making money. I did not find any trouble in getting credit, because those who knew me had faith in me. You can get an idea of how strong their confidence was when I tell you that when I finally stopped trading on credit I owed well over one million dollars.

The trouble was not that I had lost my grip but that during those four wretched years the opportunities for making money simply didn’t exist. Still I plugged along, trying to make a stake and succeeding only in increasing my indebtedness. After I ceased trading on my own hook because I wouldn’t owe my friends any more money I made a living handling accounts for people who believed I knew the game well enough to beat it even in a dull market. For my services I received a percentage of the profits—when there were any. That is how I lived. Well, say that is how I sustained life.

Of course, I didn’t always lose, but I never made enough to allow me materially to reduce what I owed. Finally, as things got worse, I felt the beginnings of discouragement for the first time in my life.

Everything seemed to have gone wrong with me. I did not go about bewailing the descent from millions and yachts to debts and the simple life. 14.1 I didn’t enjoy the situation, but I did not fill up with self-pity. I did not propose to wait patiently for time and Providence to bring about the cessation of my discomforts. I therefore studied my problem. It was plain that the only way out of my troubles was by making money. To make money I needed merely to trade successfully. I had so traded before and I must do so once more. More than once in the past I had run up a shoe string into hundreds of thousands. Sooner or later the market would offer me an opportunity.

I convinced myself that whatever was wrong was wrong with me and not with the market. Now what could be the trouble with me? I asked myself that question in the same spirit in which I always study the various phases of my trading problems. I thought about it calmly and came to the conclusion that my main trouble came from worrying over the money I owed. I was never free from the mental discomfort of it. I must explain to you that it was not the mere consciousness of my indebtedness. Any business man contracts debts in the course of his regular business. Most of my debts were really nothing but business debts, due to what were unfavourable business conditions for me, and no worse than a merchant suffers from, for instance, when there is an unusually prolonged spell of unseasonable weather. 14.2

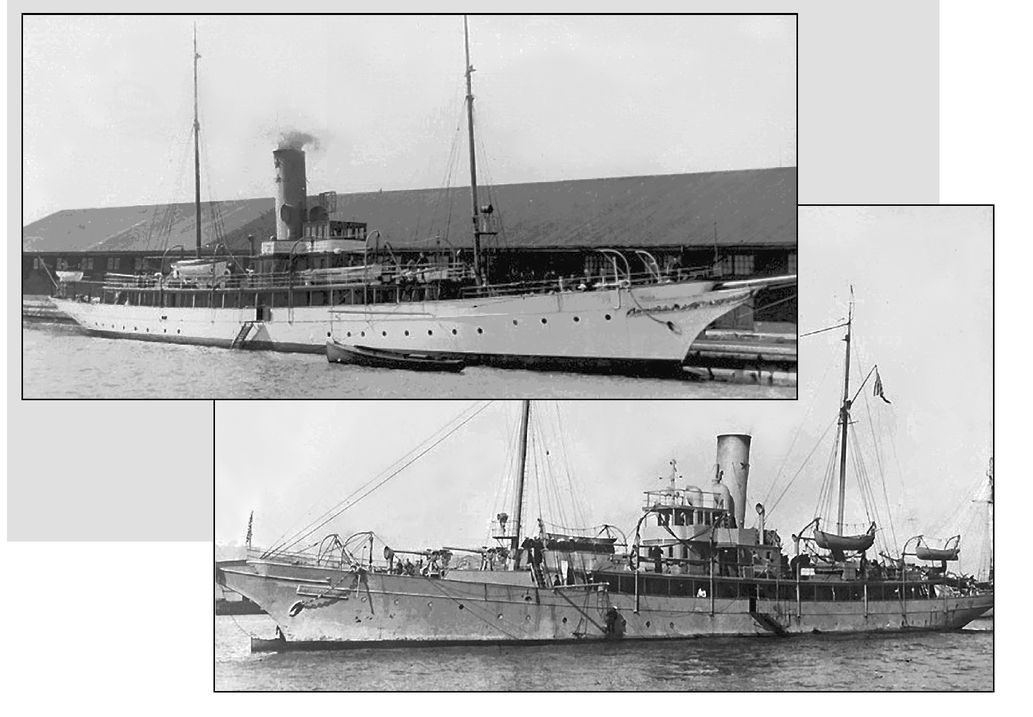

4.1Livermore actually owned two steam yachts during this period, the Venetia and he

Anita.

1 The Venetia was originally purchased in 1908 from Morton F. Plant, a yachtsman, railroad man, and financier. Plant’s father had established the Plant System of railroads that were eventually absorbed into the Atlantic Coast Line, an early predecessor of CSX Transportation.

2,

3

The Venetia displaced 580 tons and stretched 310 feet long with a beam of 51 feet. Its crew consisted of “eight sailors, three engineers, one ice plant man, two oilers, two firemen, two coal passers and one electrician,”

4 according to one account. The ship had eight staterooms, four bathrooms, a smoking room, a dining room, and a pantry and galley.

5The Venetia had witnessed a number of adventures by the time Livermore acquired it. In 1905, it sailed through the Strait of Gibraltar and cruised the Mediterranean Sea before returning home via the Bermuda Islands.

6 During that trip, the Venetia came to the rescue of the French schooner St. Antonie de Padua in the Gulf of Bougie on the north coast of Africa. Although the Venetia suffered some damage, it saved the other ship from certain loss.

7The Anita was previously owned by John H. Flagler, founder of the National Tube Co. (which was eventually merged into J. P. Morgan’s U.S. Steel).

8 The yacht was 202 feet long.

Although Livermore loved both of his yachts, he would not own them for long. Because of the losses he suffered in cotton speculation with Theodore Price, Livermore turned over the Anita to cover a $50,000 brokerage account.

9 By 1910, the Venetia had passed to John D. Spreckels of San Francisco, whose fortune originated in the Hawaiian sugar business.

10 The Venetia was commandeered by the U.S. Navy in 1917 and, after being armed with three-inch guns and depth charges, served with distinction in World War I against German submarines.

11 Photos show the Venetia when owned by Livermore, top, and when outfi tted for World War I subchasing, below.

The strain on Livermore at this time was severe, but his family tried to cover for him. In July 1909, reporters tracked down Livermore’s wife at her father’s house in the Washington, D.C., area. In her words, “The stories emanating from New York that, because Mr. Livermore is absent from his offices there, he is financially embarrassed, are all bosh.”

12 She went on to claim that he was out west on mining business.

14.2 Livermore was not the only one to compare stock speculators with merchants. Chicago commodity trader Arthur W. Cutten, one of the most successful and notorious grain pool operators and individual investors of the era, had a few words to say about it:

The chief temperamental distinction I think between a merchant and a speculator is that when a merchant has a small profit, his fingers itch to take it. All his training inspires him to keep turning over his capital. Sometimes as I have observed merchants engaged in speculation, they have seemed to be most daring

when they thought they were being cautious.

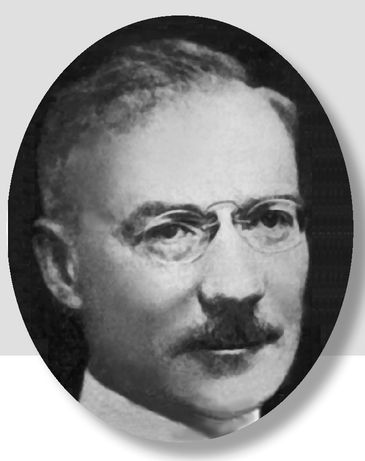

13A fragile, uptight, childless speculator partial to wearing pince-nez glasses, stiff collars and going to bed early, Cutten was one of Livermore’s most bitter nemeses during the 1920s.

14,

15 Born in a farming community in eastern Ontario, he had a natural affinity for trading agricultural products, and became wealthy trading wheat and other grains by 1906. He built a large fortune during the boom years of the 1920s before losing $50 million in the 1929 crash.

16 But ever nimble, he turned bearish in 1930 and restored his fortune.

17Cutten was vilified in the 1930s by the media, which had turned against speculators not long after it had been lionizing them, and was hounded by regulators and prosecutors over accusations of market manipulation and tax evasion.

18 He was exonerated of the manipulation charges in a landmark Supreme Court decision and died with a net worth of $50 million to $100 million.

19Of course as time went on and I could not pay I began to feel less philosophical about my debts. I’ll explain: I owed over a million dollars—all of it stock-market losses, remember. Most of my creditors were very nice and didn’t bother me; but there were two who did bedevil me. They used to follow me around. Every time I made a winning each of them was Johnny-on-the-spot, wanting to know all about it and insisting on getting theirs right off. One of them, to whom I owed eight hundred dollars, threatened to sue me, seize my furniture, and so forth. I can’t conceive why he thought I was concealing assets, unless it was that I didn’t quite look like a stage hobo about to die of destitution.

As I studied the problem I saw that it wasn’t a case that called for reading the tape but for reading my own self. I quite cold-bloodedly reached the conclusion that I would never be able to accomplish anything useful so long as I was worried, and it was equally plain that I should be worried so long as I owed money. I mean, as long as any creditor had the power to vex me or to interfere with my coming back by insisting upon being paid before I could get a decent stake together. This was all so obviously true that I said to myself, “I must go through bankruptcy.” What else could relieve my mind?

It sounds both easy and sensible, doesn’t it? But it was more than unpleasant, I can tell you. I hated to do it. I hated to put myself in a position to be misunderstood or misjudged. I myself never cared much for money. I never thought enough of it to consider it worth while lying for. But I knew that everybody didn’t feel that way. Of course I also knew that if I got on my feet again I’d pay everybody off, for the obligation remained. But unless I was able to trade in the old way I’d never be able to pay back that million.

I nerved myself and went to see my creditors. It was a mighty difficult thing for me to do, for all that most of them were personal friends or old acquaintances.

I explained the situation quite frankly to them. I said: “I am not going to take this step because I don’t wish to pay you but because, in justice to both myself and you, I must put myself in a position to make money. I have been thinking of this solution off and on for over two years, but I simply didn’t have the nerve to come out and say so frankly to you. It would have been infinitely better for all of us if I had. It all simmers down to this: I positively cannot be my old self while I am harassed or upset by these debts. I have decided to do now what I should have done a year ago. I have no other reason than the one I have just given you.”

What the first man said was to all intents and purposes what all of them said. He spoke for his firm.

“Livingston,” he said, “we understand. We realise your position perfectly. I’ll tell you what we’ll do: we’ll just give you a release. Have your lawyer prepare any kind of paper you wish, and we’ll sign it.”

That was in substance what all my big creditors said. That is one side of Wall Street for you. It wasn’t merely careless good nature or sportsmanship. It was also a mighty intelligent decision, for it was clearly good business. I appreciated both the good will and the business gumption.

These creditors gave me a release on debts amounting to over a million dollars. But there were the two minor creditors who wouldn’t sign off. One of them was the eight-hundred-dollar man I told you about. I also owed sixty thousand dollars to a brokerage firm which had gone into bankruptcy, and the receivers, who didn’t know me from Adam, were on my neck early and late. Even if they had been disposed to follow the example set by my largest creditors I don’t suppose the court would have let them sign off. At all events my schedule of bankruptcy amounted to only about one hundred thousand dollars; though, as I said, I owed well over a million.

4.3In February 1915, a New York Times headline blared, “Cotton ‘King’ a Bankrupt.”

20 The article explained that as a result of stock-transaction losses from 1913 to 1914, Livermore was voluntarily filing for bankruptcy with debts of $102,474. His main creditor was the brokerage firm Mitchell & Co. Livermore’s assets included 5,600 shares of the West Tonopah Consolidated Mining Co., 15 shares of Long Island Motor Parkway preferred, and 7 shares of the common.

By June, Livermore’s debts had been discharged. It was said that his creditors “did not press him for payment of his debts, because in most instances he had previously paid many times the sums concerned in commissions.”

21 None of his creditors contested his discharge from bankruptcy.

4.4 Still reeling from the aftermath of the Panic of 1907 and a serious recession in 1913, the financial markets suffered through the short but painful Panic of 1914, spurred by the outbreak of war in Europe. Foreign investors rapidly sold American securities and repatriated the profits, resulting in gold exports and a tightening of money. Complicating matters was the recent formation of the Federal Reserve System. New Federal Reserve notes were not ready to be placed in circulation.

New York Times financial editor and historian Alexander Dana Noyes believed the United States avoided catastrophe by closing the New York Stock Exchange between July and December 1914:

Therefore the question of how great the decline of prices would have been with the market open, the whole world in a panic, Stock Exchange prices crumbling and the banks calling loans and throwing the collateral on the market, is a matter of pure conjecture. If New York had continued to provide an open stock market during financial Europe’s bewilderment…it is not impossible that foreign selling would have driven down…the already very low prices of securities. That might very possibly have forced… widespread insolvency of private bankers or of the

banks themselves.

22There were problems in the real economy too. Concerns that Europe would be unable to accept the U.S. crop resulted in plummeting commodity prices. The U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve reacted by securing a cotton loan fund of $100 million from commercial banks to assist farmers pinched by price declines. Moreover, to help ease worries over German submarines and the effect on shipping volumes, the Treasury created a war-risk insurance plan.

Meanwhile, steel ingot production dropped from 2.5 million tons in March 1914 to just 1.6 million tons in No- vember. Employment at U.S. Steel dropped from 228,000 to 179,000. Economist Charles Gilbert wrote:

So suddenly did the impact of war make itself felt that export trade was, in August 1914, completely demoralized. Trade with our principal European customers, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, was completely cut off by both the collapse of the foreign exchange market and credits, and the lack of ocean transportation. The situation was extremely serious.

234.5Livermore had called in more than a few favors from the brokers he frequented. It was not just the $500 loan from E. F. Hutton. The New York Sun wrote in 1910 that “Jesse Livermore…got help from his brokers more than once when he had sustained reverses.”

24 This was not an unusual occurrence; the newspaper added, “Brokers with whom big operators have done business often interpose to save these operators from complete loss when the market goes against them.”

25 This was done, of course, to protect a valuable source of commission revenue.

It was extremely disagreeable to see the story in the newspapers. 4.3 I had always paid my debts in full and this new experience was most mortifying to me. I knew I’d pay off everybody some day if I lived, but everybody who read the article wouldn’t know it. I was ashamed to go out after I saw the report in the newspapers. But it all wore off presently and I cannot tell you how intense was my feeling of relief to know that I wasn’t going to be harried any more by people who didn’t understand how a man must give his entire mind to his business—if he wishes to succeed in stock speculation.

My mind now being free to take up trading with some prospect of success, unvexed by debts, the next step was to get another stake. The Stock Exchange had been closed from July thirty-first to the middle of December, 1914, and Wall Street was in the dumps. 4.4 There hadn’t been any business whatever in a long time. I owed all my friends. I couldn’t very well ask them to help me again just because they had been so pleasant and friendly to me, when I knew that nobody was in a position to do much for anybody.

It was a mighty difficult task, getting a decent stake, for with the closing of the Stock Exchange there was nothing that I could ask any broker to do for me. 4.5 tried in a couple of places. No use.

Finally I went to see Dan Williamson. This was in February, 1915. I told him that I had rid myself of the mental incubus of debt and I was ready to trade as of old. You will recall that when he needed me he offered me the use of twenty-five thousand dollars without my asking him.

Now that I needed him he said, “When you see something that looks good to you and you want to buy five hundred shares go ahead and it will be all right.”

I thanked him and went away. He had kept me from making a great deal of money and the office had made a lot in commissions from me. I admit I was a little sore to think that Williamson & Brown didn’t give me a decent stake. I intended to trade conservatively at first. It would make my financial recovery easier and quicker if I could begin with a line a little better than five hundred shares. But, anyhow, I realised that, such as it was, there was my chance to come back.

I left Dan Williamson’s office and studied the situation in general and my own problem in particular. It was a bull market. That was as plain to me as it was to thousands of traders. But my stake consisted merely of an offer to carry five hundred shares for me. That is, I had no leeway, limited as I was. I couldn’t afford even a slight setback at the beginning. I must build up my stake with my very first play. That initial purchase of mine of five hundred shares must be profitable. I had to make real money. I knew that unless I had sufficient trading capital I would not be able to use good judgment. Without adequate margins it would be impossible to take the cold-blooded, dispassionate attitude toward the game that comes from the ability to afford a few minor losses such as I often incurred in testing the market before putting down the big bet.

I think now that I found myself then at the most critical period of my career as a speculator. If I failed this time there was no telling where or when, if ever, I might get another stake for another try. It was very clear that I simply must wait for the exact psychological moment.

I didn’t go near Williamson & Brown’s. I mean, I purposely kept away from them for six long weeks of steady tape reading. I was afraid that if I went to the office, knowing that I could buy five hundred shares, I might be tempted into trading at the wrong time or in the wrong stock. A trader, in addition to studying basic conditions, remembering market precedents and keeping in mind the psychology of the outside public as well as the limitations of his brokers, must also know himself and provide against his own weaknesses. There is no need to feel anger over being human. I have come to feel that it is as necessary to know how to read myself as to know how to read the tape. I have studied and reckoned on my own reactions to given impulses or to the inevitable temptations of an active market, quite in the same mood and spirit as I have considered crop conditions or analysed reports of earnings.

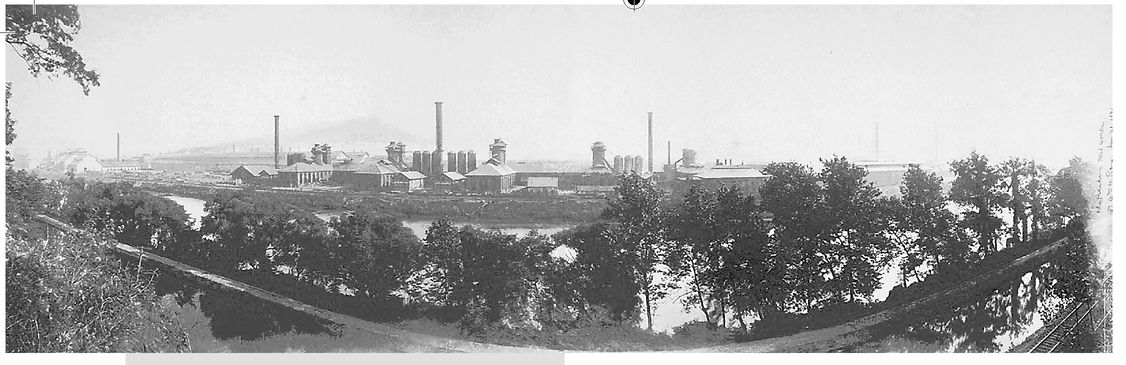

4.6 As World War I raged, it became increasingly clear that a prolonged conflict would dramatically increase the demand for steel. Gun barrels had to be forged. Battleships had to be built. In this context, the steel stocks were due for an advance. Bethlehem Steel, based in eastern Pennsylvania, would be one of them.

The company’s history dated to 1857. But the company of Livermore’s era was really born when former U.S. Steel president Charles Schwab bought majority ownership in 1901 and started to revitalize the company. According to Schwab biographer Robert Hessen: “Bethlehem Steel had been a small, specialty producer; within a decade after Schwab took control he had made it into the second largest and most diversified steel company in America.”

26Bethlehem began a close relationship with the U.S. Navy in 1887 when the company was awarded a large contract for expensive heavy forgings to be used for naval guns and armor. In fact, in 1896, it completely dismantled its rail production machinery to focus exclusively on forgings. (Photo above shows Bethlehem Steel plant in 1896.) In 1904, Schwab took his first official tour of Bethlehem’s properties. He told a reporter: “I shall make the Bethlehem plant the greatest armor plate and gun factory in the world.”

27In addition to its steel works, Bethlehem owned a number of shipyards, the most important one being the Union Iron Works in San Francisco. Clearly, the outbreak of a world war would be very profitable for Bethlehem’s operations. But building American warships was not what made the company famous.

Structural steel, better known as the modern I-beam, was the company’s claim to fame. It was invented by Henry Grey in 1897, first put into production in 1902 in Luxembourg, and embraced by Bethlehem in 1906.

28 Bethlehem Steel would go on to provide the steel for much of America’s iconic structures, including the Golden Gate Bridge, the George Washington Bridge, the Hoover Dam, and the Chrysler Building. The company went bankrupt during the 2001 recession. Its assets were sold to International Steel Group, owned by conglomerateur Wilbur Ross, which went on to merge with Mittal Steel of India in 2005; that business then went on to merge with Arcelor of Luxembourg to become the world’s largest steelmaker in 2006.

So day after day, broke and anxious to resume trading, I sat in front of a quotation-board in another broker’s office where I couldn’t buy or sell as much as one share of stock, studying the market, not missing a single transaction on the tape, watching for the psychological moment to ring the full-speed-ahead bell.

By reason of conditions known to the whole world the stock I was most bullish on in those critical days of early 1915 was Bethlehem Steel. 14.6 I was morally certain it was going way up, but in order to make sure that I would win on my very first play, as I must, I decided to wait until it crossed par.

I think I have told you it has been my experience that whenever a stock crosses 100 or 200 or 300 for the first time, it nearly always keeps going up for 30 to 50 points—and after 300 faster than after 100 or 200. One of my first big coups was in Anaconda, which I bought when it crossed 200 and sold a day later at 260. My practice of buying a stock just after it crossed par dated back to my early bucket-shop days. It is an old trading principle.

You can imagine how keen I was to get back to trading on my old scale. I was so eager to begin that I could not think of anything else; but I held myself in leash. I saw Bethlehem Steel climb, every day, higher and higher, as I was sure it would, and yet there I was checking my impulse to run over to Williamson & Brown’s office and buy five hundred shares. I knew I simply had to make my initial operation as nearly a cinch as was humanly possible.

Every point that stock went up meant five hundred dollars I had not made. The first ten points’ advance meant that I would have been able to pyramid, and instead of five hundred shares I might now be carrying one thousand shares that would be earning for me one thousand dollars a point. But I sat tight and instead of listening to my loud-mouthed hopes or to my clamorous beliefs I heeded only the level voice of my experience and the counsel of common sense. Once I got a decent stake together I could afford to take chances. But without a stake, taking chances, even slight chances, was a luxury utterly beyond my reach. Six weeks of patience—but, in the end, a victory for common sense over greed and hope!

I really began to waver and sweat blood when the stock got up to 90. Think of what I had not made by not buying, when I was so bullish. Well, when it got to 98 I said to myself, “Bethlehem is going through 100, and when it does the roof is going to blow clean off!” The tape said the same thing more than plainly. In fact, it used a megaphone. I tell you, I saw 100 on the tape when the ticker was only printing 98. And I knew that wasn’t the voice of my hope or the sight of my desire, but the assertion of my tape-reading instinct. So I said to myself, “I can’t

14.7The sinking of the Lusitania on May 7, 1915, sent waves of concern through the trading floors. The New York Times wrote: “Panic conditions reigned in the stock market…following receipt of dispatches confirming earlier reports that the Lusitania had been sunk. Stocks of all classes were thrown overboard.”

29 Panic conditions lasted only half an hour before a strong rally reversed some of the losses. Bethlehem Steel fell from a high of $159 to a low of $130 before recovering to close at $145. The day’s trading resulted in the largest percentage losses for the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the Dow Jones Transportation Average for all of 1915 at -- 4.5% and --1.9% respectively.

30

Although we do not know the circumstances of Livermore’s misfortunes during this episode, he surely was not alone. The New York Times reported: wait until it gets through 100. I have to get it now. It is as good as gone through par.”

The news came out of a clear sky when many stocks were close to the top of a sudden rise, and the downward movement of some of the specialties not only ignored fractions but skipped whole points. It was small wonder that seasoned office managers and floor members lost their heads and made mistakes, especially as the ticker was so far behind the market that quotations were a poor measure of what was happening at the time on the

Exchange.31I rushed to Williamson & Brown’s office and put in an order to buy five hundred shares of Bethlehem Steel. The market was then 98. I got five hundred shares at 98 to 99. After that she shot right up, and closed that night, I think, at 114 or 115. I bought five hundred shares more.

The next day Bethlehem Steel was 145 and I had my stake. But I earned it. Those six weeks of waiting for the right moment were the most strenuous and wearing six weeks I ever put in. But it paid me, for I now had enough capital to trade in fair-sized lots. I never would have got anywhere just on five hundred shares of stock.

There is a great deal in starting right, whatever the enterprise may be, and I did very well after my Bethlehem deal—so well, indeed, that you would not have believed it was the selfsame man trading. As a matter of fact I wasn’t the same man, for where I had been harassed and wrong I was now at ease and right. There were no creditors to annoy and no lack of funds to interfere with my thinking or with my listening to the truthful voice of experience, and so I was winning right along.

All of a sudden, as I was on my way to a sure fortune, we had the Lusitania break. 14.7Every once in a while a man gets a crack like that in the solar plexus, probably that he may be reminded of the sad fact that no human being can be so uniformly right on the market as to be beyond the reach of unprofitable accidents. I have heard people say that no professional speculator need have been hit very hard by the news of the torpedoing of the Lusitania, and they go on to tell how they had it long before the Street did. I was not clever enough to escape by means of advance information, and all I can tell you is that on account of what I lost through the Lusitania break and one or two other reverses that I wasn’t wise enough to foresee, I found myself at the end of 1915 with a balance at my brokers’ of about one hundred and forty thousand dollars. That was all I actually made, though I was consistently right on the market throughout the greater part of the year.

I did much better during the following year. I was very lucky. I was rampantly bullish in a wild bull market. Things were certainly coming my way so that there wasn’t anything to do but to make money. It made me remember a saying of the late H. H. Rogers, of the Standard Oil Company, to the effect that there were times when a man could no more help making money than he could help getting wet if he went out in a rainstorm without an umbrella. It was the most clearly defined bull market we ever had. It was plain to everybody that the Allied purchases of all kinds of supplies here made the United States the most prosperous nation in the world. We had all the things that no one else had for sale, and we were fast getting all the cash in the world. I mean that the wide world’s gold was pouring into this country in torrents. 14.8Inflation was inevitable, and, of course, that meant rising prices for everything.

All this was so evident from the first that little or no manipulation for the rise was needed. That was the reason why the preliminary work was so much less than in other bull markets. And not only was the war-bride boom more naturally developed than all others but it proved unprecedentedly profitable for the general public. That is, the stock-market winnings during 1915 were more widely distributed than in any other boom in the history of Wall Street. 14.9That the public did not turn all their paper profits into good hard cash or that they did not long keep what profits they actually took was merely history repeating itself. Nowhere does history indulge in repetitions so often or so uniformly as in Wall Street. When you read contemporary accounts of booms or panics the one thing that strikes you most forcibly is how little either stock speculation or stock speculators to-day differ from yesterday. The game does not change and neither does human nature.

14.8In 1915 and 1916, the United States received some $950 million in gold as demand for exports swelled. The yellow metal came from a number of sources. The Russian Imperial Bank sent $340 million of its gold reserves. The British diverted the total production of its South African mines in these two years—totaling some $500 million—to America. The Bank of England and the Bank of France were responsible for the remainder.

32

By April 1917, when the United States entered the war, the allied powers had purchased $7 billion worth of American food and war materiel. By the end of the war in 1918, U.S. exports had nearly tripled while imports merely doubled. The difference, net exports, was directly responsible for the rapid economic growth of this period. The Federal Reserve Board’s Index of Industrial Production, which reached a low of 39 in November 1914, reached 54 in May 1915 and jumped to 75 the following year.

33 Financial historian Margaret Myers wrote:

Employment rapidly increased, unemployment was almost eliminated, and new workers were added to the workforce. The increased buying power of the workers, and the smaller volume of consumer goods in the market, as production was shifted from consumer goods to war goods, were significant factors in the price increases which soon

appeared.3414.9The stock market enjoyed an incredible year in 1915. After a long streak of bad luck, Livermore had caught a break. The Dow Jones Industrial Average gained 82% to close at 99.15. The Dow Transports added 22% to end the year at 108.05.

35

14.10 The Dow Industrials ran to a high of 110.15 on November 21, 1916, before sliding to close the year at 95. The Dow Transports hit a high of 108.28 on October 4 before falling to 105.15.

36 I went along with the rise in 1916. 14.10I was as bullish as the next man, but of course I kept my eyes open. I knew, as everybody did, that there must be an end, and I was on the watch for warning signals. I wasn’t particularly interested in guessing from which quarter the tip would come and so I didn’t stare at just one spot. I was not, and I never have felt that I was, wedded indissolubly to one or the other side of the market. That a bull market has added to my bank account or a bear market has been particularly generous I do not consider sufficient reason for sticking to the bull or the bear side after I receive the get-out warning. A man does not swear eternal allegiance to either the bull or the bear side. His concern lies with being right.

And there is another thing to remember, and that is that a market does not culminate in one grand blaze of glory. Neither does it end with a sudden reversal of form. A market can and does often cease to be a bull market long before prices generally begin to break. My long expected warning came to me when I noticed that, one after another, those stocks which had been the leaders of the market reacted several points from the top and—for the first time in many months—did not come back. Their race evidently was run, and that clearly necessitated a change in my trading tactics.

It was simple enough. In a bull market the trend of prices, of course, is decidedly and definitely upward. Therefore whenever a stock goes against the general trend you are justified in assuming that there is something wrong with that particular stock. It is enough for the experienced trader to perceive that something is wrong. He must not expect the tape to become a lecturer. His job is to listen for it to say “Get out!” and not wait for it to submit a legal brief for approval.

As I said before, I noticed that stocks which had been the leaders of the wonderful advance had ceased to advance. They dropped six or seven points and stayed there. At the same time the rest of the market kept on advancing under new standard bearers. Since nothing wrong had developed with the companies themselves, the reason had to be sought elsewhere. Those stocks had gone with the current for months. When they ceased to do so, though the bull tide was still running strong, it meant that for those particular stocks the bull market was over. For the rest of the list the tendency was still decidedly upward.

There was no need to be perplexed into inactivity, for there were really no cross currents. I did not turn bearish on the market then, because the tape didn’t tell me to do so. The end of the bull market had not come, though it was within hailing distance. Pending its arrival there was still bull money to be made. Such being the case, I merely turned bearish on the stocks which had stopped advancing and as the rest of the market had rising power behind it I both bought and sold.

The leaders that had ceased to lead I sold. I put out a short line of five thousand shares in each of them; and then I went long of the new leaders. The stocks I was short of didn’t do much, but my long stocks kept on rising. When finally these in turn ceased to advance I sold them out and went short—five thousand shares of each. By this time I was more bearish than bullish, because obviously the next big money was going to be made on the down side. While I felt certain that the bear market had really begun before the bull market had really ended, I knew the time for being a rampant bear was not yet. There was no sense in being more royalist than the king; especially in being so too soon. The tape merely said that patrolling parties from the main bear army had dashed by. Time to get ready.

I kept on both buying and selling until after about a month’s trading I had out a short line of sixty thousand shares—five thousand shares each in a dozen different stocks which earlier in the year had been the public’s favourites because they had been the leaders of the great bull market. It was not a very heavy line; but don’t forget that neither was the market definitely bearish.

14.11Rumors plagued the stock exchange throughout 1916. There was not a fear of war but a fear of peace and the consequences for the booming economy. This was a curious development compared to the reactions to previous conflicts, such as the Russo-Japanese War of 1904, the Boer War, and the Civil War. In all those cases, the concern was that the wars would continue to interfere with normal trade flows and consume productive capital. Peace used to be the bulls’ weapon.

What changed all this was the unique position of the United States to profit from the hostilities by attracting new gold inflows. Because of the appreciation of security and commodity prices, as well as the intense capital investments made by American businesses, peace would bring about a damaging bout of deflation. As a result, when peace rumors floated around Wall Street in March and again in October, violent declines of up to 20% resulted.

In December, President Wilson asked the warring nations to state their purposes so that “some common ground” could be found to “get together and arrange the settlement,” according to a State Department note sent to all the involved parties.

37 As a result, Noyes said, “something like a panic occurred in speculative markets—not only on the Stock Exchange, where the decline in prices was the most violent of the whole war period, but in the grain market also.”

38 But these peace overtures were short-lived.

The December break was when Livermore really came back big. There were, however, questions surrounding the leaking of information about Wilson’s letter to Wall Street. Livermore’s old broker, E. F. Hutton, was forced to testify before Congress concerning a wire he received from his correspondent in Washington. According to a Wall Street Journal report of the hearing, Hutton received a telegram to the effect that “a highly important message had been issued from Washington to belligerents and neutrals.”

39 Eventually, the proceedings ended with no charges filed.

As part of the investigation, Livermore’s profits were exposed through the statements of his broker Oliver Harriman, of Harriman & Co., who was an uncle of E. H. Harriman. He said that at the time of the break, his customer was short some $7 million worth of shares. The resulting profits were estimated to be between $800,000 and $1 million. The New York Times wrote:

Mr. Harriman said he had rather not give the name of the operator, but from the signature “

J.L.L.” to telegrams sent over the Harriman wire to Washington on the peace situation it was surmised that he was Jesse

L. Livermore, who is known to have been recently a “short” trader. Mr. Harriman said his customer was

in the south. Mr. Livermore is at Palm Beach, Fla.40Then one day the entire market became quite weak and prices of all stocks began to fall. When I had a profit of at least four points in each and every one of the twelve stocks that I was short of, I knew that I was right. The tape told me it was now safe to be bearish, so I promptly doubled up.

I had my position. I was short of stocks in a market that now was plainly a bear market. There wasn’t any need for me to push things along. The market was bound to go my way, and, knowing that, I could afford to wait. After I doubled up I didn’t make another trade for a long time. About seven weeks after I put out my full line, we had the famous “leak,” and stocks broke badly. It was said that somebody had advance news from Washington that President Wilson was going to issue a message that would bring back the dove of peace to Europe in a hurry. Of course the war-bride boom was started and kept up by the World War, and peace was a bear item. When one of the cleverest traders on the floor was accused of profiting by advance information he simply said he had sold stocks not on any news but because he considered that the bull market was overripe. I myself had doubled my line of shorts seven weeks before.

On the news the market broke badly and I naturally covered. 14.11It was the only play possible. When something happens on which you did not count when you made your plans it behooves you to utilise the opportunity that a kindly fate offers you. For one thing, on a bad break like that you have a big market, one that you can turn around in, and that is the time to turn your paper profits into real money. Even in a bear market a man cannot always cover one hundred and twenty thousand shares of stock without putting up the price on himself. He must wait for the market that will allow him to buy that much at no damage to his profit as it stands him on paper.

I should like to point out that I was not counting on that particular break at that particular time for that particular reason. But, as I have told you before, my experience of thirty years as a trader is that such accidents are usually along the line of least resistance on which I base my position in the market. Another thing to bear in mind is this: Never try to sell at the top. It isn’t wise. Sell after a reaction if there is no rally.

I cleared about three million dollars in 1916 by being bullish as long as the bull market lasted and then by being bearish when the bear market started. As I said before, a man does not have to marry one side of the market till death do them part.

That winter I went South, to Palm Beach, as I usually do for a vacation, because I am very fond of salt-water fishing. I was short of stocks and wheat, and both lines showed me a handsome profit. There wasn’t anything to annoy me and I was having a good time. Of course unless I go to Europe I cannot really be out of touch with the stock or commodities markets. For instance, in the Adirondacks I have a direct wire from my broker’s office to my house. 14.12

In Palm Beach I used to go to my broker’s branch office regularly. I noticed that cotton, in which I had no interest, was strong and rising. About that time—this was in 1917—I heard a great deal about the efforts that President Wilson was making to bring about peace. The reports came from Washington, both in the shape of press dispatches and private advices to friends in Palm Beach. That is the reason why one day I got the notion that the course of the various markets reflected confidence in Mr. Wilson’s success. With peace supposedly close at hand, stocks and wheat ought to go down and cotton up. I was all set as far as stocks and wheat went, but I had not done anything in cotton in some time.

14.12 Livermore bought a house on Lake Placid, in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York, around this time. In August 1925, the New York Times reported that Livermore had begun ”conducting his operations” in stocks from his lodge in Lake Placid after having been out of the market for a year following heavy losses the summer before.

41 He had been short stocks in anticipation of the election of Calvin Coolidge, but the market soared 30% that year. The Times said he took a 50,000-share position in U.S. Steel at his Lake Placid retreat, and an ”important position” in White Motors.

42

14.13By December, after Wilson had narrowly won reelection, the Allied Powers jointly rebuffed Germany’s compromise proposal and stated terms that Germany in turn rejected two weeks later. Finally, in January 1917, German diplomats warned the United States that it would adopt a policy of “forcibly preventing … in a zone around Great Britain, France, Italy and in the Eastern Mediterranean, all navigation, that of neutrals included,” adding that “all ships met within the zone will be sunk.”

43

In early February the market broke badly on word that relations with Germany were souring quickly and the United States might be forced to enter the war. As a result of its unrestricted submarine policy, American ships were hunted in the open sea. Further complicating American neutrality were Berlin’s overtures to the Mexican government, encouraging it join with the Central Powers and attack the United States to reclaim its lost territory. By April, Congress had voted to declare war on Germany.

At 2:20 that afternoon I did not own a single bale, but at 2:25 my belief that peace was impending made me buy fifteen thousand bales as a starter. I proposed to follow my old system of trading—that is, of buying my full line—which I have already described to you.

That very afternoon, after the market closed, we got the Unrestricted Warfare note. There wasn’t anything to do except to wait for the market to open the next day. I recall that at Gridley’s that night one of the greatest captains of industry in the country was offering to sell any amount of United States Steel at five points below the closing price that afternoon. There were several Pittsburgh millionaires within hearing. Nobody took the big man’s offer. They knew there was bound to be a whopping big break at the opening.

Sure enough, the next morning the stock and commodity markets were in an uproar, as you can imagine. Some stocks opened eight points below the previous night’s close. 14.13To me that meant a heaven-sent opportunity to cover all my shorts profitably. As I said before, in a bear market it is always wise to cover if complete demoralisation suddenly develops. That is the only way, if you swing a good-sized line, of turning a big paper profit into real money both quickly and without regrettable reductions. For instance, I was short fifty thousand shares of United States Steel alone. Of course I was short of other stocks, and when I saw I had the market to cover in, I did. My profits amounted to about one and a half million dollars. It was not a chance to disregard.

Cotton, of which I was long fifteen thousand bales, bought in the last half hour of the trading the previous afternoon, opened down five hundred points. Some break! It meant an overnight loss of three hundred and seventy-five thousand dollars. While it was perfectly clear that the only wise play in stocks and wheat was to cover on the break I was not so clear as to what I ought to do in cotton. There were various things to consider, and while I always take my loss the moment I am convinced I am wrong, I did not like to take that loss that morning. Then I reflected that I had gone South to have a good time fishing instead of perplexing myself over the course of the cotton market. And, moreover, I had taken such big profits in my wheat and in stocks that I decided to take my loss in cotton. I would figure that my profit had been a little more than one million instead of over a million and a half. It was all a matter of bookkeeping, as promoters are apt to tell you when you ask too many questions.

If I hadn’t bought that cotton just before the market closed the day before, I would have saved that four hundred thousand dollars. It shows you how quickly a man may lose big money on a moderate line. My main position was absolutely correct and I benefited by an accident of a nature diametrically opposite to the considerations that led me to take the position I did in stocks and wheat. Observe, please, that the speculative line of least resistance again demonstrated its value to a trader. Prices went as I expected, notwithstanding the unexpected market factor introduced by the German note. If things had turned out as I had figured I would have been 100 per cent right in all three of my lines, for with peace stocks and wheat would have gone down and cotton would have gone kiting up. I would have cleaned up in all three. Irrespective of peace or war, I was right in my position on the stock market and in wheat and that is why the unlooked-for event helped. In cotton I based my play on something that might happen outside of the market—that is, I bet on Mr. Wilson’s success in his peace negotiations. It was the German military leaders who made me lose the cotton bet.

When I returned to New York early in 1917 I paid back all the money I owed, which was over a million dollars. 14.14It was a great pleasure to me to pay my debts. I might have paid it back a few months earlier, but I didn’t for a very simple reason. I was trading actively and successfully and I needed all the capital I had. I owed it to myself as well as to the men I considered my creditors to take every advantage of the wonderful markets we had in 1915 and 1916. I knew that I would make a great deal of money and I wasn’t worrying because I was letting them wait a few months longer for money many of them never expected to get back. I did not wish to pay off my obligations in driblets or to one man at a time, but in full to all at once. So as long as the market was doing all it could for me I just kept on trading on as big a scale as my resources permitted.

14.14 In January, Livermore was proudly telling reporters how he “came back” and that he was no longer a gambler but a “business speculator.”

44 Although he did not confirm or deny a rumor that he had cleared $3.5 million recently, he explained how he earned his new stake and offered some advice:

I must have made a very large amount, for I have paid in full for my mistakes of the past, and they cost me $2,000,000. I did not make this new fortune as I made my former one. It was not a case of gambling all on one turn. I made this fortune on several issues—cotton, grain and “war brides.” This Wall Street game is a psychological one.

The first requisite to success is confidence in one’s self. I never lost my nerve. Usually a man buys and then, when the stock goes up a few points, he is fearful that it will go down again and he will lose the little he had made. That is the wrong time to fear.

He should know that the very fact that the stock has gone up proves he is right, and he should hold on. But he sells through fear. Don’t try to scalp the market. It does not pay. Buy one issue. Don’t pyramid, for by doing that you wipe out your profit percentage. Apply just the same principles to the market that you

would to a business. Go on your own judgment.45Livermore immediately returned to his spendthrift ways. In February, he bought his wife a $120,000 emerald ring and a fast speedboat that he called the “submarine catcher.”

46 He also hired a train from Jacksonville to Palm Beach after the scheduled train had no berths on its lower level. He did not want to climb into the upper berth .

47 I wished to pay interest, but all those creditors who had signed releases positively refused to accept it. The man I paid off the last of all was the chap I owed the eight hundred dollars to, who had made my life a burden and had upset me until I couldn’t trade. I let him wait until he heard that I had paid off all the others. Then he got his money. I wanted to teach him to be considerate the next time somebody owed him a few hundreds.

And that is how I came back.

After I paid off my debts in full I put a pretty fair amount into annuities. I made up my mind I wasn’t going to be strapped and uncomfortable and minus a stake ever again. Of course, after I married I put some money in trust for my wife. And after the boy came I put some in trust for him. 14.15

The reason I did this was not alone the fear that the stock market might take it away from me, but because I knew that a man will spend anything he can lay his hands on. By doing what I did my wife and child are safe from me.

More than one man I know has done the same thing, but has coaxed his wife to sign off when he needed the money, and he has lost it. But I have fixed it up so that no matter what I want or what my wife wants, that trust holds. It is absolutely safe from all attacks by either of us; safe from my market needs; safe even from a devoted wife’s love. I’m taking no chances!

14.15 This was actually Livermore’s second marriage. His first wife was Nettie Jordan, a girl from Indianapolis that he met during his time in St. Louis.

48 Livermore and Jordan were wed in Boston in 1900.

49 He liked say it was Nettie that first made him famous: “The first time I ever got in print was when my wife came back from Europe in 1901 with $12,000 in jewels in her handbag. I had to pay $7,200 duty, and the customs took the jewels and held them overnight.”

50

Later, Livermore spent a large sum trying to help Nettie’s brother, Chester Jordan, a vaudeville performer, avoid the electric chair for the brutal murder and dismemberment of his wife. After the happy days in 1908, cruising about the Venetia after winning big in July cotton, Livermore’s relationship with Nettie quickly soured. He neglected her as he struggled to recover from the disastrous operation with Theodore Price, being suckered by the protectors of Charles E. Pugh’s estate, and the flat market in the years preceding World War I. A separation was long in coming. Nettie told the Lake Placid News in the fall of 1917 that despite Livermore’s absence, she wanted to fight to make it work:

As for me, I will never divorce him. He may harass me and hurt me, but I shall never stoop to divorce….If Mr. Livermore has some other woman in mind whom he should like to marry, he will find that idea hard to carry out. It will be quite impossible for I shall never release him. He may torment me

and humiliate me, but I shall stick by him.51Eventually, Nettie realized that Livermore’s heart had moved on. In November 1918, she filed for divorce in Reno, Nevada.

52 A month later, he married showgirl and cabaret singer Dorothy Fox Wendt of Brooklyn.

53 He had spent considerable time with the young girl “of rare beauty” during the previous summer at Lake Placid in the Adirondacks.

54 At the time of their marriage, Livermore was 41 years old. His new wife was just 23. After the ceremony at the St. Regis Hotel in New York City, the two honeymooned in Atlantic City. Inside her wedding band read a vow: “Dotsie, for ever and ever, J.L.”

55 On September 19, 1919, Jesse Livermore Jr. was born.

56 Paul Livermore followed in 1921.

ENDNOTES

1 “Yachts at Port Jefferson,”

New York Sun, January 10, 1909, 13.

2 “Morton F. Plant Dies,”

New York Times, November 5, 1918, 13.

3 “Henry B. Plant Dead,”

New York Times, June 24, 1899, 1.

4 “Quartermaster of Plant’s Yacht,”

Pensacola Journal, March 31, 1906, 3.

5 “Elkins Yacht Sold,”

New York Times, September 30, 1910, 9.

6 “America Has 3,389 Yachts,” New York Times, June 4, 1905, 21.

7 “Saved by Mr. Plant’s Yacht,”

New York Times, February 1905, 1.

8 “John H. Flagler, Capitalist, Dies,”

New York Times, September 9, 1922, 9.

9 “His Boat, His Security,”

Boston Daily Globe, August 8, 1909, 9.

10 “Elkins Yacht Sold,”

New York Times, September 30, 1910, 9.

11 “War Raider Venetia Sold,”

New York Times, November 8, 1939, 4.

12 “Mrs. Livermore Says Husband Is in the West on Mining Business,”

Washington Times, July 22, 1909.

13 Richard Wycoff,

Stock Market Technique: Number Two, (1989), 38.

14 John Brooks,

Once in Goldonda: A True Drama of Wall Street 1920-1938, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1969), 78.

15 Kenneth L. Fisher, 100 Minds

That Made the Market, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1993), 330.

16 Edwin C. Sims,

Capitalism in Spite of It All, (Gordon & Breach Science Publishers, 1969).

17 Kenneth L. Fisher,

100 Minds That Made the Market, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1993), 332.

18 “Cutten Is Indicted Over $414,525 Tax.”

New York Times. March 11, 1936, 6.

19 Kenneth L. Fisher,

100 Minds That Made the Market, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1993), 330.

20 “Cotton ‘King’ a Bankrupt,”

New York Times, February 18, 1915, 5.

21 “Livermore’s Slate Clean,”

New York Times, June 8, 1915, 9.

22 Alexander D. Noyes,

The War Period of American Finance: 1908-1925 (1926), 59-60.

23 Charles Gilbert,

American Financing of World War I (1970), 23.

24 “Gossip of Wall Street,”

New York Sun, February 9, 1910, 11.

26 Robert Hessen,

Steel Titan: The Life of Charles M. Schwab (1975), 163.

29 “Stocks Collapse on Lusitania News,”

New York Times, May 8, 1915, 3.

30 Peter Wyckoff,

Wall Street and the Stock Markets (1972), 193.

31 “Topics in Wall Street,”

New York Times, May 8, 1915, 3.

32 William J. Shultz and M. R. Caine,

Financial Development of the United States (1937), 506-507.

33 Gilbert,

American Financing of World War I, 34.

34 Margaret G. Myers,

A Financial History of the United States (1970), 272.

35 Wyckoff,

Wall Street and the Stock Markets, 176.

37 Noyes,

War Period of American Finance.

39 “Advance News on Message Sent from Washington,”

Wall Street Journal, February 1, 1917, 2.

40 “ ‘Leak’ Hunt Closed; Bolling Quits Firm,”

New York Times, February 16, 1917, 5.

41 “Livermore Trading Again.”

New York Times, August 26, 1925, Business Section, 24.

43 Noyes,

The War Period of American Finance.

44 “Jesse L. Livermore in the Swim Again,”

Boston Daily Globe, January 11, 1917, 16.

46 “Livermore Buys Emerald,”

New York Times, February 24, 1917, 3.

47 “Livermore Hires a Train,”

New York Times, February 16, 1917, 11.

48 Maury Klein,

Rainbow’s End: The Crash of 1929 (2001), 65.

49 “Says She Will Not Sue for Divorce,”

Lake Placid News, September 14, 1917, 2.

50 “Jesse Livermore Ends Life in Hotel,”

New York Times, November 29, 1940, 1.

51 “Says She Will Not Sue for Divorce.”

52 “Jesse Livermore Weds,”

Lake Placid News, December 6, 1918, 1.

53 “Report Jesse Livermore Has Married Actress,”

Boston Daily Globe, December 4, 1918, 7.

54 “Jesse Livermore Weds.”

55 Richard Smitten, Jesse Livermore:

World’s Greatest Stock Trader (2001 ), 126.

56 “The Cradle,”

Lake Placid News, September 19, 1919, 6.