XV

Among the hazards of speculation the happening of the unexpected—I might even say of the unexpectable—ranks high. There are certain chances that the most prudent man is justified in taking—chances that he must take if he wishes to be more than a mercantile mollusk. Normal business hazards are no worse than the risks a man runs when he goes out of his house into the street or sets out on a railroad journey. When I lose money by reason of some development which nobody could foresee I think no more vindictively of it than I do of an inconveniently timed storm. Life itself from the cradle to the grave is a gamble and what happens to me because I do not possess the gift of second sight I can bear undisturbed. But there have been times in my career as a speculator when I have both been right and played square and nevertheless I have been cheated out of my earnings by the sordid unfairness of unsportsmanlike opponents.

Against misdeeds by crooks, cowards and crowds a quick-thinking or far-sighted business man can protect himself. I have never gone up against downright dishonesty except in a bucket shop or two because even there honesty was the best policy; the big money was in being square and not in welshing. I have never thought it good business to play any game in any place where it was necessary to keep an eye on the dealer because he was likely to cheat if unwatched. But against the whining welsher the decent man is powerless. Fair play is fair play. I could tell you a dozen instances where I have been the victim of my own belief in the sacredness of the pledged word or of the inviolability of a gentlemen’s agreement. I shall not do so because no useful purpose can be served thereby.

15.1Lefevre has a virtually inexhaustible supply of synonyms for swindle. “Boodle” was primarily slang for bribes or illicit payments. According to A New Dictionary of Americanisms, published in 1902, it was a Dutch-derived word that was also popular in the thieving community for counterfeit money.

1 An 1875 book about the U.S. Secret Service refers to passers of fake U.S. money as “boodle carriers” and to a “boodle game” as a “cheating process.”

2

Market manipulation and unfair trading practices were a key focus of Lefevre as a journalist, but he shows Livermore as a righteous actor who played fair and rarely blamed losses on fraud.

15.2The move toward basing market views on observed facts rather than tips or gut instinct was an important step in Livermore’s development. This statement most likely also reflected a hot debate in the 1910s over the mutability of truth. The new pragmatist approach of popular philosopher William James—which held that the value of any truth was dependent on its use to the person who held it—was gaining acceptance and discussed avidly in the media.

The battle between philosophies of truth—objective, intrinsic, deductive, relative, or religious—came to a boil a decade later during the Scopes trial in Tennessee. Former presidential candidate and congressman William Jennings Bryan, in testimony for the prosecution, challenged the scientific process by calling evolution “millions of guesses strung together.”

The debate over what constitutes reliable information for investors continues to rage today. Proponents of the efficient market hypothesis—the consensus paradigm of stock behavior of the 1970s and 1980s—believe that prices on traded assets reflect all known knowledge and quickly change to reflect new data. In other words, they believe that price always tells the truth. A new school of thought, called behavioral economics, upended that view in the 1990s by asserting that investors regularly hold false beliefs due to cognitive biases such as overconfidence, overreaction, and improper use of linear reasoning.

It is likely that Livermore would have leaned toward the latter camp, as he believed his role as a thinking speculator was to find people who held false beliefs about price and trade against them.

Fiction writers, clergymen and women are fond of alluding to the floor of the Stock Exchange as a boodlers’ battlefield and to Wall Street’s daily business as a fight. 15.1

It is quite dramatic but utterly misleading. I do not think that my business is strife and contest. I never fight either individuals or speculative cliques. I merely differ in opinion—that is, in my reading of basic conditions. What playwrights call battles of business are not fights between human beings. They are merely tests of business vision. I try to stick to facts and facts only, and govern my actions accordingly. 15.2That is Bernard M. Baruch’s recipe for success in wealth-winning. 15.3Sometimes I do not see the facts—all the facts—clearly enough or early enough; or else I do not reason logically. Whenever any of these things happen I lose. I am wrong. And it always costs me money to be wrong.

No reasonable man objects to paying for his mistakes. There are no preferred creditors in mistake-making and no exceptions or exemptions. But I object to losing money when I am right. I do not mean, either, those deals that have cost me money because of sudden changes in the rules of some particular exchange. I have in mind certain hazards of speculation that from time to time remind a man that no profit should be counted safe until it is deposited in your bank to your credit.

After the Great War broke out in Europe there began the rise in the prices of commodities that was to be expected. It was as easy to foresee that as to foresee war inflation. Of course the general advance continued as the war prolonged itself. As you may remember, I was busy “coming back” in 1915. The boom in stocks was there and it was my duty to utilise it. My safest, easiest and quickest big play was in the stock market, and I was lucky, as you know.

By July, 1917, I not only had been able to pay off all my debts but was quite a little to the good besides.

Bernard Mannes Baruch is probably known today for his role as a trusted advisor to President Franklin Roosevelt. But in the first two decades of the twentieth century, he was admired both as a cunning speculator who made a fortune before age 30 and as a war advisor to President Woodrow Wilson.

Baruch was born in Camden, South Carolina, in 1870. His father was a Prussia-born Jew who immigrated to the United States to escape military service, found work as a bookkeeper in a rural South Carolina general store, went to medical school under the sponsorship of his boss, Mannes Baum, and served as a Confederte Army surgeon during the Civil War. Baruch’s other, Belle, was the daughter of a Jewish plantation owner, Sailin g Wolfe, who lost a fortune when his estate was burned to the ground and his slaves were freed by General Sherman of the Union Army.

3Dr. Baruch’s medical practice was slow to grow in war-ravaged Camden, but the family was still among the most prosperous in town. The area was too backwoods for his wife, though, so after the dueling death of a close friend, the family moved to the lightly populated Upper East Side of New York in 1880. Dr. Baruch soon developed a successful new medical practice from scratch and became a leading advocate for clean water.

4 By the late 1890s, the family was successful enough to afford servants, although they were not considered truly rich.

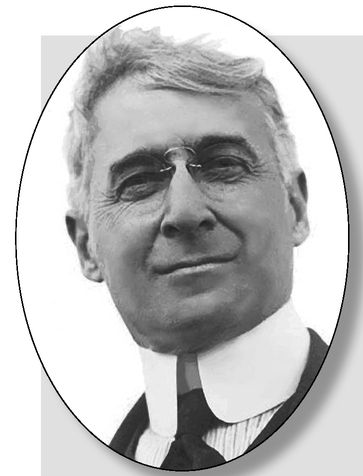

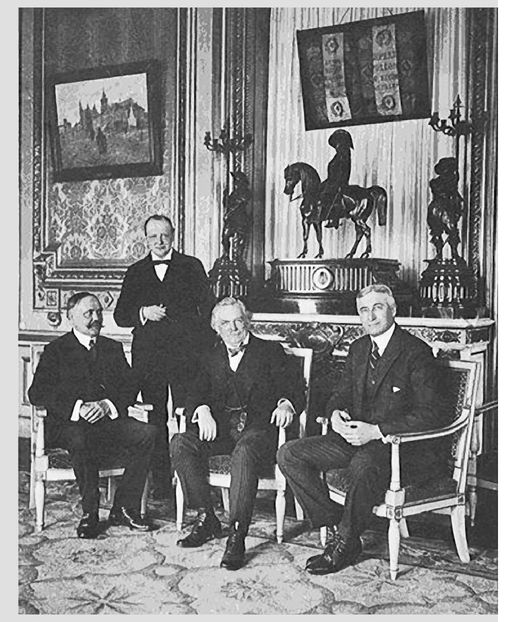

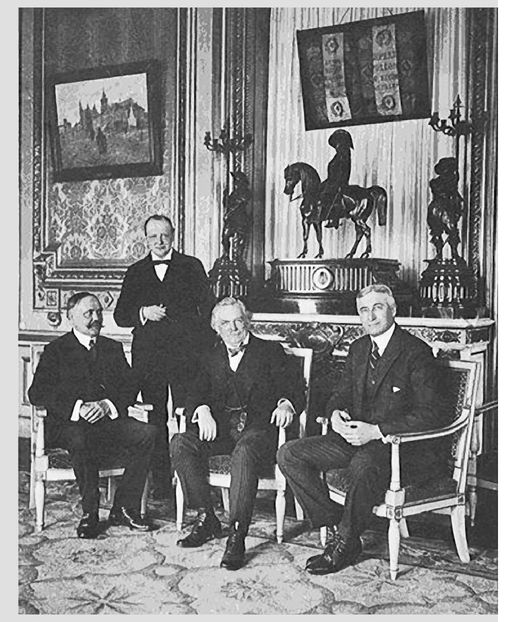

5At left, Bernard Baruch in 1919. Above, seated at far right during the Versailles Peace Conference, he served as an advisor to President Wilson. To his left are Louis Loucheur, Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George.

Baruch had his heart set on attending Yale University but his mother wanted him close to home, so he started at City College of New York at age 14. After his graduation in 1889, his mother helped him get a job with a friend who had a seat on the stock exchange. He started as an unpaid apprentice and was soon learning about speculation, arbitrage, and foreign exchange; it was not long before he became useful enough to earn the princely sum of $3 a week.

6 A year later, he took off for Colorado to try to strike it rich in the new gold and silver mines, completing the last leg of the trip by stagecoach. He gambled and boxed in his spare time and later liked to quote British ring champion Bob Fitzsimmons, who watched him beat a taller opponent after several tough early rounds. The quip was appropriate for his later career as a speculator. “A fight is never over until one man is out,” said Fitzsimmons. “As long as you ain’t that man you have a chance. To be a champion you have to learn to take it or you can’t give it.”

7Baruch, who never lost his southern accent, ultimately returned home to work on Wall Street again and became an analyst and gofer for legendary tycoon James Keene. Speculating on his own, using margin because of his small capital base, he made and lost hundreds of thousands of dollars as he learned his craft. He became a broker and partner at A. A. Housman & Co., and started a brokerage after gaining a reputation as “the Lone Wolf on Wall Street” because of his preference, like Livermore later, to play his own hand.

After becoming a millionaire speculating in sugar and stocks and emerging as a role model for younger traders like Livermore, Baruch would serve President Wilson during World War I as a national defense consultant and later as an advisor at the Versailles Peace Conference. He prospered during the 1920s, did not lose his fortune in the 1929 crash, and played a key role as an advisor to President Roosevelt during the New Deal and World War II. He later became an expert on nuclear disarmament in the Truman administration and died at age 94 in 1965. With a life experience spanning from the Civil War to the Cold War, he certainly did merit Livermore’s early admiration.

15.4Livermore’s yearlong adventure with coffee in 1917 amply illustrates four of his main themes: the benefi ts of anticipation and patience; the unfairness of manipulation; the fact that government interference in commodity prices never lasts; and the need to expect the “unexpectable.” He says, “I object to losing money when I am right” not as sour grapes but as just one more lesson learned. He added later that postmortems in speculation are a waste of time but observed that this episode—in which he was correct to think that U.S. coffee prices would soar during World War I but never made a dime because importers lobbied the government to set price limits—at least had educational value.

This meant that I now had the time, the money and the inclination to consider trading in commodities as well as in stocks. For many years I have made it my practice to study all the markets. The advance in commodity prices over the pre-war level ranged from 100 to 400 per cent. There was only one exception, and that was coffee. Of course there was a reason for this. The breaking out of the war meant the closing up of European markets and huge cargoes were sent to this country, which was the one big market. That led in time to an enormous surplus of raw coffee here, and that, in turn, kept the price low. Why, when I first began to consider its speculative possibilities coffee was actually selling below pre-war prices. If the reasons for this anomaly were plain, no less plain was it that the active and increasingly efficient operation by the German and Austrian submarines must mean an appalling reduction in the number of ships available for commercial purposes. This eventually in turn must lead to dwindling imports of coffee. With reduced receipts and an unchanged consumption the surplus stocks must be absorbed, and when that happened the price of coffee must do what the prices of all other commodities had done, which was, go way up. 15.4

It didn’t require a Sherlock Holmes to size up the situation. Why everybody did not buy coffee I cannot tell you. When I decided to buy it I did not consider it a speculation. It was much more of an investment. I knew it would take time to cash in, but I knew also that it was bound to yield a good profit. That made it a conservative investment operation—a banker’s act rather than a gambler’s play.

I started my buying operations in the winter of 1917. I took quite a lot of coffee. The market, however, did nothing to speak of. It continued inactive and as for the price, it did not go up as I had expected. The outcome of it all was that I simply carried my line to no purpose for nine long months. My contracts expired then and I sold out all my options. I took a whopping big loss on that deal and yet I was sure my views were sound. I had been clearly wrong in the matter of time, but I was confident that coffee must advance as all commodities had done, so that no sooner had I sold out my line than I started in to buy again. I bought three times as much coffee as I had so unprofitably carried during those nine disappointing months. Of course I bought deferred options—for as long a time as I could get.

I was not so wrong now. As soon as I had taken on my trebled line the market began to go up. People everywhere seemed to realise all of a sudden what was bound to happen in the coffee market. It began to look as if my investment was going to return me a mighty good rate of interest.

The sellers of the contracts I held were roasters, mostly of German names and affiliations, who had bought the coffee in Brazil confidently expecting to bring it to this country. But there were no ships to bring it, and presently they found themselves in the uncomfortable position of having no end of coffee down there and being heavily short of it to me up here.

Please bear in mind that I first became bullish on coffee while the price was practically at a pre-war level, and don’t forget that after I bought it I carried it the greater part of a year and then took a big loss on it. The punishment for being wrong is to lose money. The reward for being right is to make money. Being clearly right and carrying a big line, I was justified in expecting to make a killing. It would not take much of an advance to make my profit satisfactory to me, for I was carrying several hundred thousand bags. I don’t like to talk about my operations in figures because sometimes they sound rather formidable and people might think I was boasting. As a matter of fact I trade in accordance to my means and always leave myself an ample margin of safety. In this instance I was conservative enough.

15.5Lefevre’s distaste for coffee industry insiders who demanded price controls on their product when they were short the commodity is evident in this highly sarcastic remark. Of course he means they were neither philanthropic nor patriotic but rather out for their own interests when they appealed to the government for a limit on prices.

President Wilson set up the War Industries Board in July 1917, four months after the country’s late entrance into World War I, to unify the federal government’s relationship with strategic industries and ensure the availability of key raw materials at reasonable prices. This was a first for the country, and his advisors squabbled among themselves and with Congress about how to mobilize.

Congress gave the president power to control food and fuel supplies and fix a minimum price for wheat and other commodities, even though most U.S. production was already committed to the French and British, who had been at war with Germany for three years. Prices were set for sales to the government—not at retail—for everything ranging from aluminum, iron, and cement to jam and beer. The program initially suffered from a lack of cooperation from manufacturers, though, so Wilson appointed Bernard Baruch to whip it into shape.

The Price Fixing Committee was added in March 1918, but because it lacked compulsory power, originally its effectiveness was limited. Baruch tried to gain industrial chiefs’ voluntary cooperation through patriotic appeals at first, but they were disdainful of the effort and not fond of being told what to do by an ex-banker. Baruch gained their help only after threatening to bring down the force of the federal government on them.

8 In the end, the committee did keep inflation low in the last year of the war, and the board ensured that the War Department got the materials it needed on time. Just as Livermore says, coffee had the smallest price increase of all food commodities during the war by a wide margin.

9A decade and a half later, President Roosevelt used the War Industries Board as a model for adjusting the forces of industrial supply and demand during the Great Depression and then re-created the board during World War II.

10 The concept that the government should command the economy during wartime was one of Baruch’s chief intellectual contributions to Roosevelt’s approach.

The reason I bought options so freely was because I couldn’t see how I could lose. Conditions were in my favour. I had been made to wait a year, but now I was going to be paid both for my waiting and for being right. I could see the profit coming—fast. There wasn’t any cleverness about it. It was simply that I wasn’t blind.

Coming sure and fast, that profit of millions! But it never reached me. No; it wasn’t side-tracked by a sudden change in conditions. The market did not experience an abrupt reversal of form. Coffee did not pour into the country. What happened? The unexpectable! What had never happened in anybody’s experience; what I therefore had no reason to guard against. I added a new one to the long list of hazards of speculation that I must always keep before me. It was simply that the fellows who had sold me the coffee, the shorts, knew what was in store for them, and in their efforts to squirm out of the position into which they had sold themselves, devised a new way of welshing. They rushed to Washington for help, and got it.

Perhaps you remember that the Government had evolved various plans for preventing further profiteering in necessities. You know how most of them worked. Well, the philanthropic coffee shorts appeared before the Price Fixing Committee of the War Industries Board—I think that was the official designation—and made a patriotic appeal to that body to protect the American breakfaster. 15.5 They asserted that a professional speculator, one Lawrence Livingston, had cornered, or was about to corner, coffee. If his speculative plans were not brought to naught he would take advantage of the conditions created by the war and the American people would be forced to pay exorbitant prices for their daily coffee. It was unthinkable to the patriots who had sold me cargoes of coffee they couldn’t find ships for, that one hundred millions of Americans, more or less, should pay tribute to conscienceless speculators. They represented the coffee trade, not the coffee gamblers, and they were willing to help the Government curb profiteering actual or prospective.

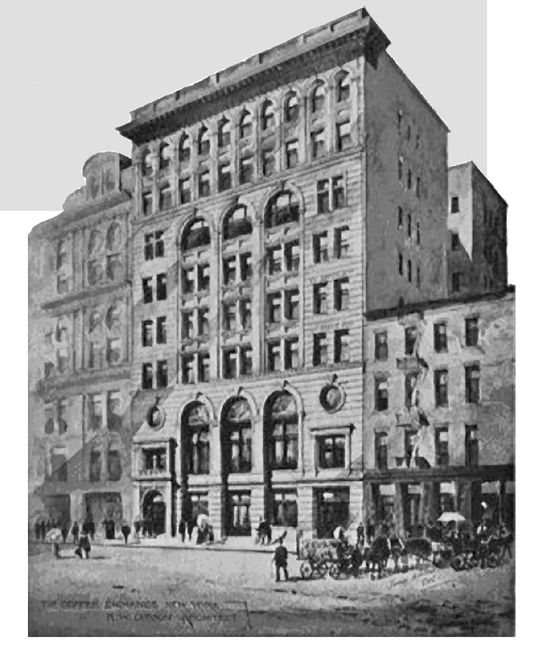

15.6 The New York Coffee Exchange was founded to trade coffee futures in 1882. It sat opposite the Cotton Exchange at the corner of William and Beaver streets in Manhattan and became the world’s first coffee trading organization of national proportions. Up to that time, coffee was traded primarily in port cities in an uncoordinated manner. Soon after, national coffee exchanges opened in Germany, the Netherlands, Great Britain, Italy, and Brazil.

11

Coffee was a big turn-of-the-century business: In 1900, 99 companies imported green coffee from Brazil and Central America to New York, and there were 6 more importers in Philadelphia, 28 in San Francisco, and 12 in New Orleans

. By 1920, there were 216 in New York, 31 in San Francisco, and 15 in New Orleans.

12 Moreover, the 1919 census counted 769 coffee shops across the country. Outside New York, the states with the most coffee shops were Pennsylvania, California, Missouri, Illinois, and Texas.

13 The exchange added sugar futures in 1914, then merged with the New York Cocoa Exchange in 1979. In 1998, that group merged with the New York Cotton Exchange and became units of the New York Board of Trade, which itself merged with the Intercontinental Exchange in 2006.

Now I have a horror of whiners and I do not mean to intimate that the Price Fixing Committee was not doing its honest best to curb profiteering and wastefulness. But that need not stop me from expressing the opinion that the committee could not have gone very deeply into the particular problem of the coffee market. They fixed on a maximum price for raw coffee and also fixed a time limit for closing out all existing contracts. This decision meant, of course, that the Coffee Exchange would have to go out of business. 15.6 There was only one thing for me to do and I did it, and that was to sell out all my contracts. Those profits of millions that I had deemed as certain to come my way as any I ever made failed completely to materialise. I was and am as keen as anybody against the profiteer in the necessaries of life, but at the time the Price Fixing Committee made their ruling on coffee, all other commodities were selling at from 250 to 400 per cent above pre-war prices while raw coffee was actually below the average prevailing for some years before the war. I can’t see that it made any real difference who held the coffee. The price was bound to advance; and the reason for that was not the operations of conscienceless speculators, but the dwindling surplus for which the diminishing importations were responsible, and they in turn were affected exclusively by the appalling destruction of the world’s ships by the German submarines. The committee did not wait for coffee to start; they clamped on the brakes.

As a matter of policy and of expediency it was a mistake to force the Coffee Exchange to close just then. If the committee had let coffee alone the price undoubtedly would have risen for the reasons I have already stated, which had nothing to do with any alleged corner. But the high price—which need not have been exorbitant—would have been an incentive to attract supplies to this market. I have heard Mr. Bernard M. Baruch say that the War Industries Board took into consideration this factor—the insuring of a supply—in fixing prices, and for that reason some of the complaints about the high limit on certain commodities were unjust. When the Coffee Exchange resumed business, later on, coffee sold at twenty-three cents. The American people paid that price because of the small supply, and the supply was small because the price had been fixed too low, at the suggestion of philanthropic shorts, to make it possible to pay the high ocean freights and thus insure continued importations.

I have always thought that my coffee deal was the most legitimate of all my trades in commodities. I considered it more of an investment than a speculation. I was in it over a year. If there was any gambling it was done by the patriotic roasters with German names and ancestry. 15.7 They had coffee in Brazil and they sold it to me in New York. The Price Fixing Committee fixed the price of the only commodity that had not advanced. They protected the public against profiteering before it started, but not against the inevitable higher prices that followed. Not only that, but even when green coffee hung around nine cents a pound, roasted coffee went up with everything else. It was only the roasters who benefited. If the price of green coffee had gone up two or three cents a pound it would have meant several millions for me. And it wouldn’t have cost the public as much as the later advance did.

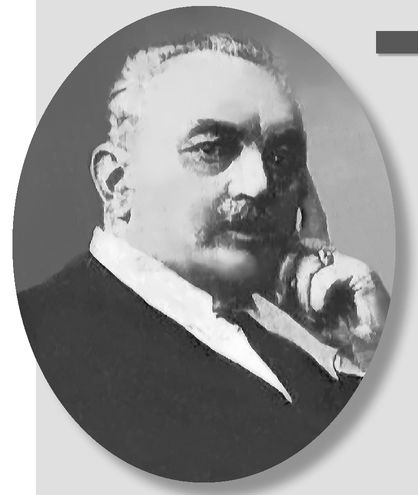

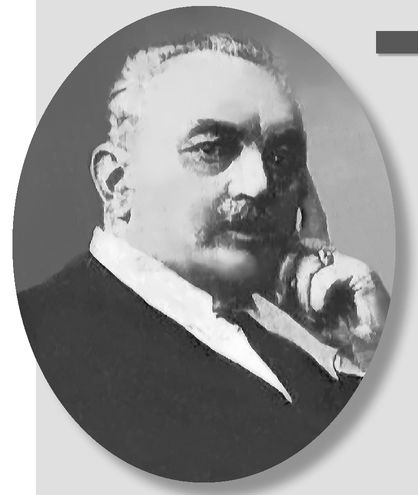

15.7Hermann Sielcken, a German who claimed American citizenship, was known as the Coffee King in the 1890s and 1910s. A biographer said he ruled the coffee markets of the world as an absolute dictator with a commanding presence. Born in Hamburg to a family in the bakery business in 1847, Sielcken shipped out to Costa Rica to work for a German firm at 21, moved on to work as a shipping clerk and then a wool buyer in San Francisco in the late 1860s, was almost killed in a stagecoach wreck in Oregon, and moved to New York to recuperate, landing a job as a clerk for a glassware importer.

14 Sielcken next found work with a merchandiser specializing in South American imports, leveraging his facility with languages. After prowling around Brazil, he drummed up enough business to earn a partnership at the fi rm W. H. Crossman & Bro., which later changed its name to Crossman & Sielcken. At that point, according to his biographer, Sielcken became a “human dynamo” of self-education and deal making in Brazil, the United States, and Germany who pushed the trading fi rm into world prominence in the coffee trade. Newspapers claimed he made the bulk of his fortune in a 1907 coffee futures corner,

15 although he always denied creating cornes to advance his own positions. hen coffee trading grew tedious, Sielcken branched out into the trading of steel and railroads stocks, where he crossed horns with John W. Gates, E. H. Harriman, and railroad magnate George J. Gould, son of the notorious speculator Jay Gould. After his first wife died, he married the daughter of Paul Isenberg, a wealthy sugar planter in the Hawaiian Islands, and the couple divided their time between a suite at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York and a lavish 200-acre estate near Baden-Baden, Germany, that was renowned for its 168 varieties of roses and its pine trees imported from Oregon.

16 He was said to love regaling guests with tales of his adventures on stagecoaches in the Wild West and in shipwrecks in South America.

Sielcken died in 1917, the year of Livermore’s coffee exploits, but his partners carried on. Livermore’s account reveals that he disliked the German-born coffee importers intensely and deplored their ability to persuade the U.S. government to limit prices. A biographer says Sielcken’s policy in coffee “was one of blood and iron,” he was “silent and uncommunicative,” exploded in rage under stress, was ruthless in dealing with men and governments, but avoided the limelight. You can just imagine the duel of wits as the crafty import house battled with the cunning speculator. Sielcken’s firm won in the end, although after the war, prices did explode higher, as Livermore had forecast.

Post-mortems in speculation are a waste of time. They get you nowhere. But this particular deal has a certain educational value. It was as pretty as any I ever went into. The rise was so sure, so logical, that I figured that I simply couldn’t help making several millions of dollars. But I didn’t.

15.8Livermore was regularly amused to fi nd himself the subject of newspaper stories during big market movements, but he understood that reporters needed to provide readers with explanations for mysterious events. He dismisses the idea that “some plunger’s operations” were responsible for big moves, observing instead that the larger forces at work were supply and demand imbalances. He believed that stories about speculators’ raids were essentially ghost stories that brokers told clients to keep them in the dark about their losses from what he considered “blind gambling.”

On two other occasions I have suffered from the action of exchange committees making rulings that changed trading rules without warning. But in those cases my own position, while technically right, was not quite so sound commercially as in my coffee trade. You cannot be dead sure of anything in a speculative operation. It was the experience I have just told you that made me add the unexpectable to the unexpected in my list of hazards.

After the coffee episode I was so successful in other commodities and on the short side of the stock market, that I began to suffer from silly gossip. The professionals in Wall Street and the newspaper writers got the habit of blaming me and my alleged raids for the inevitable breaks in prices. 15.8 At times my selling was called unpatriotic—whether I was really selling or not. The reason for exaggerating the magnitude and the effect of my operations, I suppose, was the need to satisfy the public’s insatiable demand for reasons for each and every price movement.

As I have said a thousand times, no manipulation can put stocks down and keep them down. There is nothing mysterious about this. The reason is plain to everybody who will take the trouble to think about it half a minute. Suppose an operator raided a stock—that is, put the price down to a level below its real value—what would inevitably happen? Why, the raider would at once be up against the best kind of inside buying. The people who know what a stock is worth will always buy it when it is selling at bargain prices. If the insiders are not able to buy, it will be because general conditions are against their free command of their own resources, and such conditions are not bull conditions. When people speak about raids the inference is that the raids are unjustified; almost criminal. But selling a stock down to a price much below what it is worth is mighty dangerous business. It is well to bear in mind that a raided stock that fails to rally is not getting much inside buying and where there is a raid—that is, unjustified short selling—there is usually apt to be inside buying; and when there is that, the price does not stay down. I should say that in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, so-called raids are really legitimate declines, accelerated at times but not primarily caused by the operations of a professional trader, however big a line he may be able to swing.

The theory that most of the sudden declines or particular sharp breaks are the results of some plunger’s operations probably was invented as an easy way of supplying reasons to those speculators who, being nothing but blind gamblers, will believe anything that is told them rather than do a little thinking. The raid excuse for losses that unfortunate speculators so often receive from brokers and financial gossipers is really an inverted tip. The difference lies in this: A bear tip is distinct, positive advice to sell short. But the inverted tip—that is, the explanation that does not explain—serves merely to keep you from wisely selling short. The natural tendency when a stock breaks badly is to sell it. There is a reason—an unknown reason but a good reason; therefore get out. But it is not wise to get out when the break is the result of a raid by an operator, because the moment he stops the price must rebound. Inverted tips! 15.9

15.9 This section provides a great illustration of the symbiotic relationship between Livermore and Lefevre in the creation of Reminiscences. The chapter begins as an opportunity for Livermore to explain his well-reasoned but ill-fated decision to buy coffee futures during World War I. It was a great idea that went awry due to the treachery of German-born roasters and the misguided naïveté of government price regulators. The one-time bucket shop gambler wants to make sure we know that he had ascended to the ranks of sophisticated, long-term investors.

Then he gets a shot in against those who think short sellers like himself can push a stock down that doesn’t deserve it. He points out that if a bear raid smashes the price of a commodity or company well below its intrinsic value, insiders who understand the business will swoop in and push it back up to fair value. In short he says that any stock or commodity that goes down and stays down deserves its fate, and the public’s losses should not be blamed on short sellers.

In the last few paragraphs, though, the discussion swerves over to one of Lefevre’s favorite topics, which is that the public should close their ears to stock tips. The narrator suggests that there are two kinds of bad advice on the short side of the market. A regular “bear tip” is a recommendation to sell short, usually on the theory that some famous plunger and his clique are about to gang up on a stock. An “inverted” bear tip is one that actually comes from the evil plunger himself and could be intended either to get the public to short a stock just before it rebounds so they can be wiped out on a reversal, or as a recommendation to buy just as the plunger intends to short heavily again.

Lefevre’s implicit message is: Just say no to all tips, because they’re usually a poisoned gift. By the same token, he would warn that all fund managers’ remarks in the media today are conflicted, and should be ignored. No doubt he would be appalled by financial cable television.

ENDNOTES

1 Sylva Clapin,

A New Dictionary of Americanisms (1902), 66.

2 George O. Waitt,

Three Years with Counterfeiters, Smugglers and Boodle Carriers (1875), 9.

3 James Grant,

Bernard Baruch: The Adventures of a Wall Street Legend (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997), 2.

7 Bernard Baruch,

Baruch: My Own Story (Cutchoge, NY: Buccaneer Books, 1957), 65.

8 William O’Neill,

A Democracy at War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995).

9 Simon Litman,

Prices and Price Controls in Great Britain and the United States during the World War. (1920), 102.

10 O’Neill,

Democracy at War. 11 William Harrison Ukers,

All About Coffee (New York: Tea & Coffee Trade Journal Co., 1922), 491.

15 “Herman Sielcken Reported to Be Dead,”

New York Times, November 23, 1917.

16 Ukers,

All About Coffee, 521.