XVII

17.1 Livermore was dragged in front of a Senate committee in late 1923 to discuss market manipulations and the commissions earned by pool operators.

1 One of my most intimate friends is very fond of telling stories about what he calls my hunches. He is forever ascribing to me powers that defy analysis. He declares I merely follow blindly certain mysterious impulses and thereby get out of the stock market at precisely the right time. His pet yarn is about a black cat that told me, at his breakfast-table, to sell a lot of stock I was carrying, and that after I got the pussy’s message I was grouchy and nervous until I sold every share I was long of. I got practically the top prices of the movement, which of course strengthened the hunch theory of my hard-headed friend.

I had gone to Washington 17.1 to endeavor to convince a few Congressmen that there was no wisdom in taxing us to death and I wasn’t paying much attention to the stock market. My decision to sell out my line came suddenly, hence my friend’s yarn.

I admit that I do get irresistible impulses at times to do certain things in the market. It doesn’t matter whether I am long or short of stocks. I must get out. I am uncomfortable until I do. I myself think that what happens is that I see a lot of warning-signals. Perhaps not a single one may be sufficiently clear or powerful to afford me a positive, definite reason for doing what I suddenly feel like doing. Probably that is all there is to what they call “ticker-sense” that old traders say James R. Keene 17.2 had so strongly developed and other operators before him. Usually, I confess, the warning turns out to be not only sound but timed to the minute. But in this particular instance there was no hunch. The black cat had nothing to do with it. What he tells everybody about my getting up so grumpy that morning I suppose can be explained—if I in truth was grouchy—by my disappointment. I knew I was not convincing the Congressman I talked to and the Committee did not view the problem of taxing Wall Street as I did. I wasn’t trying to arrest or evade taxation on stock transactions but to suggest a tax that I as an experienced stock operator felt was neither unfair nor unintelligent. I didn’t want Uncle Sam to kill the goose that could lay so many golden eggs with fair treatment. Possibly my lack of success not only irritated me but made me pessimistic over the future of an unfairly taxed business. But I’ll tell you exactly what happened.

17.2 Lefevre wrote an article about Keene in 1909 that reveals a lot about both the trader’s agility and the author’s view of journalists’ role in the reporting process. The piece captures Keene’s reaction to news that the United States would intervene in an 1895 boundary dispute between British Guiana and Venezuela after the discovery of gold in a remote area between the two countries.

Richard Olney, secretary of state under President Grover Cleveland, sent a strongly worded message to his British counterpart, Lord Salisbury, that invoked the Monroe Doctrine barring intervention in the Western Hemisphere by European powers. After being rebuffed by the British government, which contended that the Monroe Doctrine was not international law, Cleveland turned to Congress for authorization to create a boundary commission to settle the dispute. He proposed that its fi ndings be enforced “by every means,” which was taken to mean military force. The measure was passed and talk of war began to circulate in the press.

Lefevre wrote:

At the time the stock market was bullish. Wall Street read the message and thought nothing of it. A newspaper man, who happened to be calling on James R. Keene, expressed his surprise that the Street took it so calmly. Mr. was long about 50,000 shares in various stocks. He asked why the President’s message should have any effect. The newspaper man looked at the great stock tor in blank amazement and asked: “Have you read it?”

“I’ve read the headlines,” replied Keene impatiently. He had not shaken his mind’s position toward the stock market, which had made him buy 50,000 shares. How was today totally different from yesterday? What new market condition had been created? “Read the message: read the last paragraph. The sting is in the tail!” said the newspaper man. They sent for the message. Keene read it carefully from beginning to end.

“Well?” he said, his mind still clinging to its previous position.

“Well? You mean ‘hell’ don’t you? That’s what will break loose tomorrow when London begins to sell American stocks by the ship-load! You’ll see nothing but WAR!! in the English papers tomorrow. And the same here!”

Still, Keene hesitated. Think of it! A man of his temperament and experience and imagination hesitated! But the more he thought the more he realized that a new market condition had been created. He began selling out of the stocks he held. Freed from the handicap of his market commitments, which so often fetter the minds of operators, he then and only then grasped the situation clearly. And then, and only then, did he begin to sell short. From bull to nothing, from nothing to bear. Even the great Keene had to take these two steps. All that day he sold and sold, up to the close of the market. From being long 50,000 shares in the morning he went home at three o’clock short 73,000 shares. And the next day hell broke loose fi rst in the newspapers, then on the

Stock Exchange. And Keene made a fortune.2

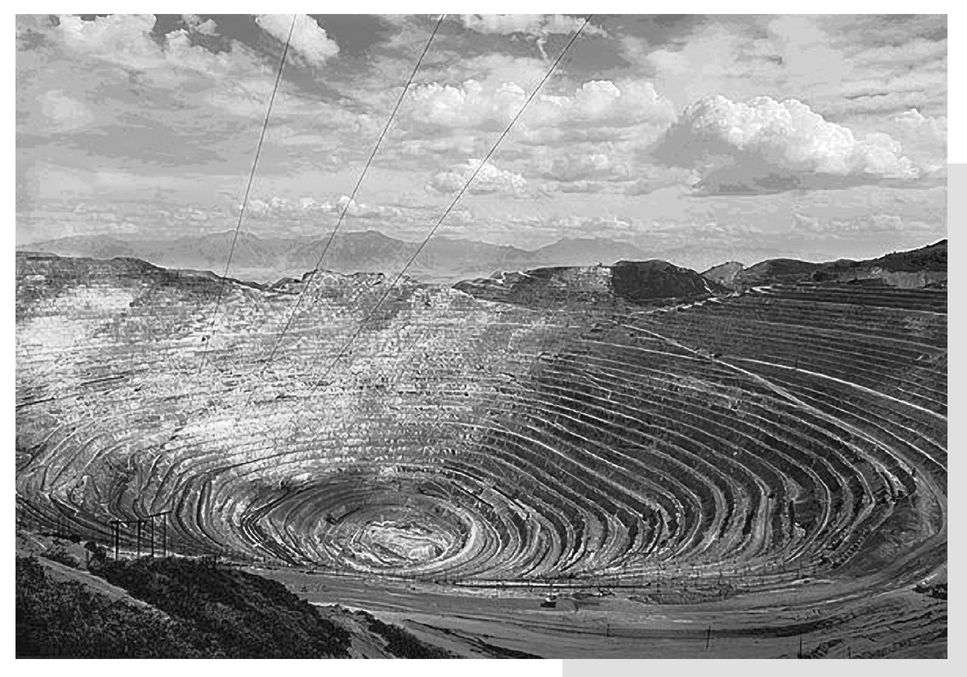

17.3 Utah Copper’s colorful history began when Enos Wall purchased low-grade copper deposits around Bingham Canyon just south of Salt Lake City in 1887. Steam shovels were brought in to work the mountain in 1906, and devel oped it into one of the most productive mines in the world, now almost a mile deep and three miles wide. Kennecott Mines Co. of Alaska bought a 25% stake in the company in 1915, and then purchased the rest in 1936. After World War II, copper prices dropped sharply and the Utah company ’s assets were sold to a succession of oil companies, starting with Standard Oil of Ohio and ending with British Petroleum. A predecessor of Australian mining conglomer ate Rio Tinto bought and reincorporated the company in 1989 and operates the Bingham mine now again as its Kennecott Utah Copper unit.

3

At the beginning of the bull market I thought well of the outlook in both the Steel trade and the copper market and I therefore felt bullish on stocks of both groups. So I started to accumulate some of them. I began by buying 5,000 shares of Utah Copper 17.3 and stopped because it didn’t act right. That is, it did not behave as it should have behaved to make me feel I was wise in buying it. I think the price was around 114. I also started to buy United States Steel at almost the same price. I bought in all 20,000 shares the first day because it did act right. I followed the method I have described before.

17.4 This narrative appears to describe the spring of 1923, when the economy was recovering from a post-World War I recession thanks to interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve. The business expansion kicked off the epic bull market of the “Roaring Twenties,” which peaked in a speculative frenzy in the final summer of the decade and ended with the October 1929 crash.

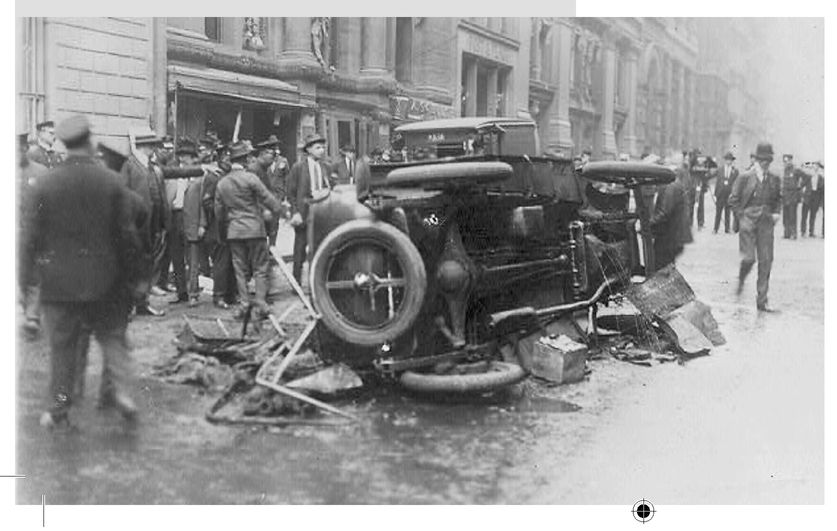

The business contraction that preceded this period was brief but very severe. It’s perhaps no surprise that Lefevre skips the post-World War I era in his narrative. Deflation ravaged asset values as industrial production slowed. Wholesale prices fell 56% from May 1920 to June 1921. The only comparable deflation occurred during the War of 1812 and the Civil War.

4 It was also a period of social strife punctuated with labor strikes and race riots. A horse-drawn wagon bomb that detonated outside the J. P. Morgan building on Wall Street, shown below, killed 38 people and wounded 300 on September 16, 1920.

5 (The case was never solved, though Italian anarchists were suspected.

6 )

The Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 28% in the year after World War I ended in November 1918, but then sank 30% over the next two years. Stocks then gradually worked their way higher until July 1924, when the new boom ensued.

You can see how the favorable conditions Livermore describes would have acted as a power tailwind for stocks as the world struggled to recover from the horrors and destruction of the world war. In 1921, the Federal Reserve slashed U.S. short-term rates to 4.5% from 7%, helping the recovery gain momentum. Historian Robert Sobel writes that inventories had reached such low levels that ”companies were forced to place new orders or go out of business.” The economy briefly tipped back into recession from May 1923 to July 1924, but industry and stocks then shifted into overdrive and never looked back for the next five years as the Dow Jones Industrials soared 270%.

7Steel continued to act right and I therefore continued to accumulate it until I was carrying 72,000 shares of it in all. But my holdings of Utah Copper consisted of my initial purchase. I never got above the 5,000 shares. Its behaviour did not encourage me to do more with it.

Everybody knows what happened. We had a big bull movement. 17.4 I knew the market was going up. General conditions were favourable. Even after stocks had gone up extensively and my paper-profit was not to be sneezed at, the tape kept trumpeting: Not yet! Not yet! When I arrived in Washington the tape was still saying that to me. Of course, I had no intention of increasing my line at that late day, even though I was still bullish. At the same time, the market was plainly going my way and there was no occasion for me to sit in front of a quotation board all day, in hourly expectation of getting a tip to get out. Before the clarion call to retreat came—barring an utterly unexpected catastrophe, of course—the market would hesitate or otherwise prepare me for a reversal of the speculative situation. That was the reason why I went blithely about my business with my Congressmen.

At the same time, prices kept going up and that meant that the end of the bull market was drawing nearer. I did not look for the end on any fixed date. That was something quite beyond my power to determine. But I needn’t tell you that I was on the watch for the tip-off. I always am, anyhow. It has become a matter of business habit with me.

I cannot swear to it but I rather suspect that the day before I sold out, seeing the high prices made me think of the magnitude of my paper-profit as well as of the line I was carrying and, later on, of my vain efforts to induce our legislators to deal fairly and intelligently by Wall Street. That was probably the way and the time the seed was sown within me. The subconscious mind worked on it all night. In the morning I thought of the market and began to wonder how it would act that day. When I went down to the office I saw not so much that prices were still higher and that I had a satisfying profit but that there was a great big market with a tremendous power of absorption. I could sell any amount of stock in that market; and, of course, when a man is carrying his full line of stocks, he must be on the watch for an opportunity to change his paper profit into actual cash. He should try to lose as little of the profit as possible in the swapping. Experience has taught me that a man can always find an opportunity to make his profits real and that this opportunity usually comes at the end of the move. That isn’t tape-reading or a hunch.

Of course, when I found that morning a market in which I could sell out all my stocks without any trouble I did so. When you are selling out it is no wiser or braver to sell fifty shares than fifty thousand; but fifty shares you can sell in the dullest market without breaking the price and fifty thousand shares of a single stock is a different proposition. I had seventy-two thousand shares of U.S. Steel. This may not seem a colossal line, but you can’t always sell that much without losing some of that profit that looks so nice on paper when you figure it out and that hurts as much to lose as if you actually had it safe in bank.

I had a total profit of about $1,500,000 and I grabbed it while the grabbing was good. But that wasn’t the principal reason for thinking that I did the right thing in selling out when I did. The market proved it for me and that was indeed a source of satisfaction to me. It was this way: I succeeded in selling my entire line of seventy-two thousand shares of U.S. Steel at a price which averaged me just one point from the top of the day and of the ovement. 17.5 It proved that I was right, to the minute. But when, on the very same hour of the very same day I came to sell my 5,000 Utah Copper, the price broke five points. Please recall that I began buying both stocks at the same time and that I acted wisely in increasing my line of U.S. Steel from twenty thousand shares to seventy-two thousand, and equally wisely in not increasing my line of Utah from the original 5,000 shares. The reason why I didn’t sell out my Utah Copper before was that I was bullish on the copper trade and it was a bull market in stocks and I didn’t think that Utah would hurt me much even if I didn’t make a killing in it. But as for hunches, there weren’t any.

17.5 On April 20, 1923, Livermore warned that the “technical position of the stock market is weak because of undigested securities.” Immediately there was a backlash as newspapers reported that bankers conspired to “teach him a lesson” and speculated that a “squeeze might shortly be engineered against him if it were found that he were short of stocks” after issuing his dire prediction.

8 By October, Livermore was turning bullish once more, telling the Christian Science Monitor, “I have no intention of staying out of the stock market permanently.”

9The training of a stock trader is like a medical education. The physician has to spend long years learning anatomy, physiology, materia medica and collateral subjects by the dozen. He learns the theory and then proceeds to devote his life to the practice. He observes and classifies all sorts of pathological phenomena. He learns to diagnose. If his diagnosis is correct—and that depends upon the accuracy of his observation—he ought to do pretty well in his prognosis, always keeping in mind, of course, that human fallibility and the utterly unforeseen will keep him from scoring 100 per cent of bull’s-eyes. And then, as he gains in experience, he learns not only to do the right thing but to do it instantly, so that many people will think he does it instinctively. It really isn’t automatism. It is that he has diagnosed the case according to his observations of such cases during a period of many years; and, naturally, after he has diagnosed it, he can only treat it in the way that experience has taught him is the proper treatment. You can transmit knowledge—that is, your particular collection of card-indexed facts—but not your experience. A man may know what to do and lose money—if he doesn’t do it quickly enough.

Observation, experience, memory and mathematics—these are what the successful trader must depend on. He must not only observe accurately but remember at all times what he has observed. He cannot bet on the unreasonable or on the unexpected, however strong his personal convictions may be about man’s unreasonableness or however certain he may feel that the unexpected happens very frequently. He must bet always on probabilities—that is, try to anticipate them. 17.6 Years of practice at the game, of constant study, of always remembering, enable the trader to act on the instant when the unexpected happens as well as when the expected comes to pass.

A man can have great mathematical ability and an unusual power of accurate observation and yet fail in speculation unless he also possesses the experience and the memory. And then, like the physician who keeps up with the advances of science, the wise trader never ceases to study general conditions, to keep track of developments everywhere that are likely to affect or influence the course of the various markets. After years at the game it becomes a habit to keep posted. He acts almost automatically. He acquires the invaluable professional attitude and that enables him to beat the game—at times! This difference between the professional and the amateur or occasional trader cannot be overemphasised. I find, for instance, that memory and mathematics help me very much. Wall Street makes its money on a mathematical basis. I mean, it makes its money by dealing with facts and figures.

When I said that a trader has to keep posted to the minute and that he must take a purely professional attitude toward all markets and all developments, I merely meant to emphasise again that hunches and the mysterious ticker-sense haven’t so very much to do with success. Of course, it often happens that an experienced trader acts so quickly that he hasn’t time to give all his reasons in advance—but nevertheless they are good and sufficient reasons, because they are based on facts collected by him in his years of working and thinking and seeing things from the angle of the professional, to whom everything that comes to his mill is grist. Let me illustrate what I mean by the professional attitude.

17.6 Anticipation was a very important theme for Livermore, one he expressed again and again to reporters who sought out his secrets. Today we would recognize the concept by the phrase “Buy the rumor and sell the news.”

William Hamilton, the fourth editor of the Wall Street Journal, wrote in 1922:

Jesse Livermore was quoted in the columns of Barron’s as saying that “all market movements are based on sound reasoning. Unless a man can anticipate future events his ability to speculate successfully is limited.” And he went on to add: “Speculation is a business. It is neither guesswork nor a gamble. It is hard work and plenty of it.”

10Separately, Livermore described his methods to Richard Wyckoff, who founded the Magazine of Wall Street:

My principal method is to study the effect of present and future conditions on the earning power of the various companies engaged in different lines of industry. Anticipation of coming events is the whole thing. When I have my mind made up about this, I wait for the psychological moment. I do not deal promiscuously; instead, I decide how much I will trade in, and how much money I will risk on that trade, and then I buy or sell the whole quantity at once.

11And finally, there is a testimony Livermore gave to the Federal Trade Commission in 1922 during a hearing on grain exporters:

Every successful player has to anticipate. If he anticipates right, see, there will come a time in the next period of two or three months that his judgment is going to be proved right by the action of the market. You see what I mean? It is going to be so plain then that everyone is going to think at some time in the future what he is thinking today, and when the time comes that everyone gets thinking, it is very plain, and the papers begin to talk and everything else, and the government agencies, and say there is going to be a scarcity of wheat, as they did last spring, and come out with a lot of misinformation and excite the public—the successful man who anticipated the situation three months previous, he would not be successful very long if he did not take advantage and sell out at that time.

12Hedge fund manager Michael Steinhardt succinctly described this process as the need to develop a “variant perception.”

13 In these comments, as well as in Lefevre’s narrative, the speculator’s art is defined less by the purely technical expectation of price movements than by a forecast of future news and market participators’ reaction to it.

17.7 Railway shopmen walked off the job between July and September 1922 to protest against wage reductions. Coal miners went on strike throughout the year in response to mining company efforts to establish separate wage contracts.

I keep track of the commodities markets, always. It is a habit of years. As you know, the Government reports indicated a winter wheat crop about the same as last year and a bigger spring wheat crop than in 1921. The condition was much better and we probably would have an earlier harvest than usual. When I got the figures of condition and I saw what we might expect in the way of yield—mathematics—I also thought at once of the coal miners’ strike and the railroad shopmen’s strike. 17.7 I couldn’t help thinking of them because my mind always thinks of all developments that have a bearing on the markets. It instantly struck me that the strike which had already affected the movement of freight everywhere must affect wheat prices adversely. I figured this way: There was bound to be considerable delay in moving winter wheat to market by reason of the strike-crippled transportation facilities, and by the time those improved the Spring wheat crop would be ready to move. That meant that when the railroads were able to move wheat in quantity they would be bringing in both crops together—the delayed winter and the early spring wheat—and that would mean a vast quantity of wheat pouring into the market at one fell swoop. Such being the facts of the case—the obvious probabilities—the traders, who would know and figure as I did, would not bull wheat for a while. They would not feel like buying it unless the price declined to such figures as made the purchase of wheat a good investment. With no buying power in the market, the price ought to go down. Thinking the way I did I must find whether I was right or not. As old Pat Hearne used to remark, “You can’t tell till you bet.” Between being bearish and selling there is no need to waste time.

Experience has taught me that the way a market behaves is an excellent guide for an operator to follow. It is like taking a patient’s temperature and pulse or noting the colour of the eyeballs and the coating of the tongue.

Now, ordinarily a man ought to be able to buy or sell a million bushels of wheat within a range of ⁄ cent. On this day when I sold the 250,000 bushels to test the market for timeliness, the price went down ¼ cent. Then, since the reaction did not definitely tell me all I wished to know, I sold another quarter of a million bushels. I noticed that it was taken in driblets; that is, the buying was in lots of 10,000 or 15,000 bushels instead of being taken in two or three transactions which would have been the normal way. In addition to the homeopathic buying the price went down 1¼ cents on my selling. Now, I need not waste time pointing out that the way in which the market took my wheat and the disproportionate decline on my selling told me that there was no buying power there. Such being the case, what was the only thing to do? Of course, to sell a lot more. Following the dictates of experience may possibly fool you, now and then. But not following them invariably makes an ass of you. So I sold 2,000,000 bushels and the price went down some more. A few days later the market’s behaviour practically compelled me to sell an additional 2,000,000 bushels and the price declined further still; a few days later wheat started to break badly 17.8 and slumped off 6 cents a bushel. And it didn’t stop there. It has been going down, with short-lived rallies.

Now, I didn’t follow a hunch. Nobody gave me a tip. It was my habitual or professional mental attitude toward the commodities markets that gave me the profit and that attitude came from my years at this business. I study because my business is to trade. The moment the tape told me that I was on the right track my business duty was to increase my line. I did. That is all there is to it.

17.8 The railroad strike created a supply overhang at a time when the U.S. economy was already suffering from price deflation in the wake of the economic distress of World War I. Also complicating matters was a large influx of grain from European nations as reconstruction of their fields and transportation infrastructure started to take hold. World wheat production swelled from nearly 3 million bushels in 1919 to more than 3.7 million.

14 From a high of $1.07 a bushel, wheat fell as low as 96.5 cents per bushel in Chicago.

15

Besides the reasons given here, there was also a rumor floating around Wall Street that Livermore believed wheat would sell at 75 cents a bushel following government hearings on the grain exchanges. As a result, the New York Times reported: “Several millions of bushels of long wheat went overboard, and the break was assisted by selling by houses that usually act for Livermore.”

1617.9 The Crucible Steel Co. of America was founded in 1900 from a combination of 13 smaller companies. It produced 95% of the country’s total supply of crucible steel and was at the time the world’s largest producer.

17 Sales offices were located all around the world, including Seattle, Boston, Berlin, London, Petrograd, and Paris.

18

In 1968, Crucible was bought by Colt Industries. In 1985, the company regained its independence after a group of employees bought it. The years that followed featured labor strikes, modernization initiatives, and increased reliance on the automobile industry. In May 2009, Crucible filed for bankruptcy protection.

19The company took its name from crucible steel, which is a high-quality metal formed under high temperatures within a crucible to increase its carbon content. In the 1830s, the United States imported all of its crucible steel for use in tools and saws from England. After a large clay deposit was discovered in West Virginia, suitable for the construction of crucibles, American manufacturers began experimenting with the process. By the 1860s, Hussey, Wells & Co. of Pittsburgh was the first to find “complete financial as well as mechanical success in this difficult department of American manufacturing enterprise.”

20 Eventually, the firm would become part of Crucible Steel. The method survives today but was largely supplanted in the mid twentieth century by the faster, lower-cost Bessemer process for mass-market steel making.

17.9 Republic Iron and Steel Co. was founded in 1899 and based in Youngstown, Ohio. Republic was combined with a few smaller competitors in 1927 to become the third largest steel producer in the United States behind Bethlehem and U.S. Steel. Eventually, the firm became part of International Steel Group, which in turn was purchased by Luxembourg-based global steelmaker ArcelorMittal.

21I have found that experience is apt to be steady dividend payer in this game and that observation gives you the best tips of all. The behaviour of a certain stock is all you need at times. You observe it. Then experience shows you how to profit by variations from the usual, that is, from the probable. For example, we know that all stocks do not move one way together but that all the stocks of a group will move up in a bull market and down in a bear market. This is a commonplace of speculation. It is the commonest of all self-given tips and the commission houses are well aware of it and pass it on to any customer who has not thought of it himself; I mean, the advice to trade in those stocks which have lagged behind other stocks of the same group. Thus, if U.S. Steel goes up, it is logically assumed that it is only a matter of time when Crucible 17.9 or Republic 17.10 or Bethlehem will follow suit. Trade conditions and prospects should work alike with all stocks of a group and the prosperity should be shared by all. On the theory, corroborated by experience times without number, that every dog has his day in the market, the public will buy A. B. Steel because it has not advanced while C. D. Steel and X. Y. Steel have gone up.

I never buy a stock even in a bull market, if it doesn’t act as it ought to act in that kind of market. I have sometimes bought a stock during an undoubted bull market and found out that other stocks in the same group were not acting bullishly and I have sold out my stock. Why? Experience tells me that it is not wise to buck against what I may call the manifest group-tendency. I cannot expect to play certainties only. I must reckon on probabilities—and anticipate them. An old broker once said to me: “If I am walking along a railroad track and I see a train coming toward me at sixty miles an hour, do I keep on walking on the ties? Friend, I side-step. And I do not even pat myself on the back for being so wise and prudent.”

Last year, after the general bull movement was well under way, I noticed that one stock in a certain group was not going with the rest of the group, though the group with that one exception was going with the rest of the market. I was long a very fair amount of Blackwood Motors. Everybody knew that the company was doing a very big business. The price was rising from one to three points a day and the public was coming in more and more. This naturally centered attention on the group and all the various motor stocks began to go up. One of them, however, persistently held back and that was Chester. It lagged behind the others so that it was not long before it made people talk. The low price of Chester and its apathy was contrasted with the strength and activity in Blackwood and other motor stocks and the public logically enough listened to the touts and tipsters and wiseacres and began to buy Chester on the theory that it must presently move up with the rest of the group.

Instead of going up on this moderate public buying, Chester actually declined. Now, it would have been no job to put it up in that bull market, considering that Blackwood, a stock of the same group, was one of the sensational leaders of the general advance and we were hearing nothing but the wonderful improvement in the demand for automobiles of all kinds and the record output. 17.11

It was thus plain that the inside clique in Chester were not doing any of the things that inside cliques invariably do in a bull market. For this failure to do the usual thing there might be two reasons. Perhaps the insiders did not put it up because they wished to accumulate more stock before advancing the price. But this was an untenable theory if you analysed the volume and character of the trading in Chester. The other reason was that they did not put it up because they were afraid of getting stock if they tried to.

17.11 There is no record of auto companies Blackwood or Chester, but the car industry was rising at this time to a prominence that it would hold for another six decades. Indeed, the distinguishing characteristic of economic expansion of the 1920s was the way it improved the standard of living of the average American.

This was a function of two developments: a rapid expansion of credit and of advertising. Historian Sobel writes: ”The magazines, newspapers, and radio were glutted with appeals to buy, to consume, to ’enhance your status,’ with the statement,‘easy credit arranged’ appended.”

22At the center of the action for Jazz Age urbanites was the automobile. Production increased sharply as the age of the railroad was eclipsed: From 1.5 million units in 1921, the industry churned out 3.6 million units by 1925.

The period was quite similar to the mortgage-fueled consumerism of the 1990s and 2000s. Sobel, speaking of the depression that was to follow, wrote: “All of these purchases took massive amounts of credit, and involved the mortgage of tomorrow for today. The American consumer was willing to make this deal, and he traded a decade of unemployment and hunger for a decade of tinsel, much like the man who sold his soul to the devil.”

23 17.12 Guiana Gold was likely a pseudonym for a stock known as Engineer’s Gold. Shares traded on the Curb Exchange and jumped over $100 a share from $55 in 192 5.

24

17.13 Livermore bought a seat on the New York Curb Market in 1920 for $5,000. It was not until 1922 that he got around to using it, as traditionally he operated out of the backrooms of brokerages or out of his private office. Livermore’s appearance at the market caused quite a stir. He walked over to the Mexico Oil post, which was the fi rst oil stock to be listed at the rival New York Stock Exchange board, and started buying, according to a newspaper account:

“Four and five-sixteenths for 1,000 Mexico,” Livermore cried. He got it. “Same for another 1,000,” he said. “Sold,” said Jimmy Lee, Tammany broker. So the game went for the hour between 11 and 12 o’clock, during which Livermore had bid for 10,000 shares and came off with a new 5,000 shares to his credit.

25When the men who ought to want a stock don’t want it, why should I want it? I figured that no matter how prosperous other automobile companies might be, it was a cinch to sell Chester short. Experiences had taught me to beware of buying a stock that refuses to follow the group-leader.

I easily established the fact that not only there was no inside buying but that there was actually inside selling. There were other symptomatic warnings against buying Chester, though all I required was its inconsistent market behaviour. It was again the tape that tipped me off and that was why I sold Chester short. One day, not very long afterward, the stock broke wide open. Later on we learned—officially, as it were—that insiders had indeed been selling it, knowing full well that the condition of the company was not good. The reason, as usual, was disclosed after the break. But the warning came before the break. I don’t look out for the breaks; I look out for the warnings. I didn’t know what was the trouble with Chester; neither did I follow a hunch. I merely knew that something must be wrong.

Only the other day we had what the newspapers called a sensational movement in Guiana Gold. 17.12 After selling on the Curb 17.13 at 50 or close to it, it was listed on the Stock Exchange. It started there at around 35, began to go down and finally broke 20.

Now, I’d never have called that break sensational because it was fully to be expected. If you had asked you could have learned the history of the company. No end of people knew it. It was told to me as follows: A syndicate was formed consisting of a half dozen extremely well-known capitalists and a prominent banking-house. One of the members was the head of the Belle Isle Exploration Company, which advanced Guiana over $10,000,000 cash and received in return bonds and 250,000 shares out of a total of one million shares of the Guiana Gold Mining Company. The stock went on a dividend basis and it was mighty well advertised. The Belle Isle people thought it well to cash in and they gave a call on their 250,000 shares to the bankers, who arranged to try to market that stock and some of their own holdings as well. They thought of entrusting the market manipulation to a professional whose fee was to be one third of the profits from the sale of the 250,000 shares above 36. I understand that the agreement was drawn up and ready to be signed but at the last moment the bankers decided to undertake the marketing themselves and save the fee. So they organized an inside pool. The bankers had a call on the Belle Isle holdings of 250,000 at 36. They put this in at 41. That is, insiders paid their own banking colleagues a 5-point profit to start with. I don’t know whether they knew it or not.

It is perfectly plain that to the bankers the operation had every semblance of a cinch. We had run into a bull market and the stocks of the group to which Guiana Gold belonged were among the market leaders. The company was making big profits and paying regular dividends. This together with the high character of the sponsors made the public regard Guiana almost as an investment stock. I was told that about 400,000 shares were sold to the public all the way up to 47.

The gold group was very strong. But presently Guiana began to sag. It declined ten points. That was all right if the pool was marketing stock. But pretty soon the Street began to hear that things were not altogether satisfactory and the property was not bearing out the high expectations of the promoters. Then, of course, the reason for the decline became plain. But before the reason was known I had the warning and had taken steps to test the market for Guiana. The stock was acting pretty much as Chester Motors did. I sold Guiana. The price went down. I sold more. The price went still lower. The stock was repeating the performance of Chester and of a dozen other stocks whose clinical history I remembered. The tape plainly told me that there was something wrong—something that kept insiders from buying it—insiders who knew exactly why they should not buy their own stock in a bull market. On the other hand, outsiders, who did not know, were now buying because having sold at 45 and higher the stock looked cheap at 35 and lower. The dividend was still being paid. The stock was a bargain.

Then the news came. It reached me, as important market news often does, before it reached the public. But the confirmation of the reports of striking barren rock instead of rich ore merely gave me the reason for the earlier inside selling. I myself didn’t sell on the news. I had sold long before, on the stock’s behaviour. My concern with it was not philosophical. I am a trader and therefore looked for one sign: Inside buying. There wasn’t any. I didn’t have to know why the insiders did not think enough of their own stock to buy it on the decline. It was enough that their market plans plainly did not include further manipulation for the rise. That made it a cinch to sell the stock short. The public had bought almost a half million shares and the only change in ownership possible was from one set of ignorant outsiders who would sell in the hope of stopping losses to another set of ignorant outsiders who might buy in the hope of making money.

I am not telling you this to moralise on the public’s losses through their buying of Guiana or on my profit through my selling of it, but to emphasise how important the study of group-behaviourism is and how its lessons are disregarded by inadequately equipped traders, big and little. And it is not only in the stock market that the tape warns you. It blows the whistle quite as loudly in commodities.

I had an interesting experience in cotton. I was bearish on stocks and put out a moderate short line. At the same time I sold cotton short; 50,000 bales. My stock deal proved profitable and I neglected my cotton. The first thing I knew I had a loss of $250,000 on my 50,000 bales. As I said, my stock deal was so interesting and I was doing so well in it that I did not wish to take my mind off it. Whenever I thought of cotton I just said to myself: “I’ll wait for a reaction and cover.” The price would react a little but before I could decide to take my loss and cover the price would rally again, and go higher than ever. So I’d decide again to wait a little and I’d go back to my stock deal and confine my attention to that. Finally I closed out my stocks at a very handsome profit and went away to Hot Springs 17.14 for a rest and a holiday.

That really was the first time that I had my mind free to deal with the problem of my losing deal in cotton. The trade had gone against me. There were times when it almost looked as if I might win out. I noticed that whenever anybody sold heavily there was a good reaction. But almost instantly the price would rally and make a new high for the move.

Finally, by the time I had been in Hot Springs a few days, I was a million to the bad and no let up in the rising tendency. I thought over all I had done and had not done and I said to myself: “I must be wrong!” With me to feel that I am wrong and to decide to get out are practically one process. So I covered, at a loss of about one million.

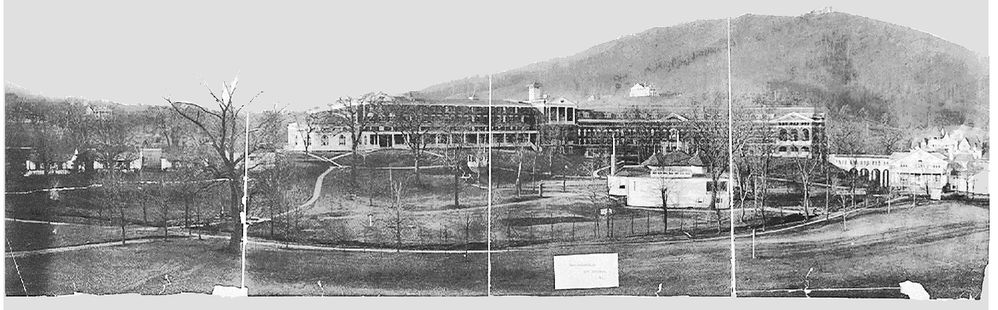

17.14 This is most likely Hot Springs, Virginia, a resort town featuring natural springs and luxury hotels. Livermore probably stayed at the Homestead Hotel, which was visited by President Taft, President Wilson, and President Coolidge during this period.

17.15 In the 1920s, cotton futures were one of the most avidly traded commodities by big Wall Street players, much as oil and copper would be decades later. Newspapers carried detailed daily reports on prices and kept close tabs on the positions held by Livermore, Cutten, and others.

Livermore in this passage shares his view that his success in the cotton market did not come from hunches, but from close observation of the way the market accepted his supply if he was selling, or reacted to his demand if he was buying. If he dumped 10,000 bales on the market and there was no rally, he felt comfortable short-selling more lots because it showed that bulls were scarce.

The fiber, which grows in a puff known as a “boll,˝ requires a lot of water, so cotton traders try to forecast rainfall and flooding prospects by tracking weather trends, as well as the public’s demand for new clothing. Most of the cotton in the United States at the time was produced in the Mississippi delta and north Texas areas, so traders tried to gain an edge on each other by determining if conditions were exceptionally dry or wet, which would impair the size of the crop and lift prices.

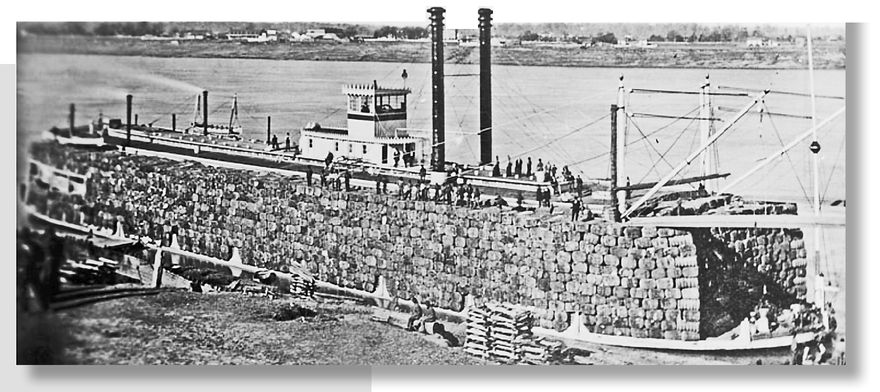

Although cotton was grown and traded in the Middle East, India and Africa in the earliest years of recorded his tory, it did not become part of an important manufactured good until Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin to mechanize cleaning in 1793, and factory-scale looms emerged during the Industrial Revolution in England. The British empire grew strong on textile exports, and while the crown merchants originally imported their cotton from India they later turned to their former American colonies due to the superior plant grown in the South and the low cost of slave labor.

After emancipation during the Civil War and well into Livermore’s era, impecunious sharecroppers and small farm ers from east Georgia to west Texas continued to produce the cotton that provided lavish fortunes to traders on Wall Street by processing, pressing, and baling it at plantations, then shipping it north to textile mills on riverboats. Above is the steamer Chas. P. Chouteau in Natchez, Mississippi, stuffed with 7,818 bales in 1878.

The next morning I was playing golf and not thinking of anything else. I had made my play in cotton. I had been wrong. I had paid for being wrong and the receipted bill was in my pocket. I had no more concern with the cotton market than I have at this moment. When I went back to the hotel for luncheon I stopped at the broker’s office and took a look at the quotations. I saw that cotton had gone off 50 points. That wasn’t anything. But I also noticed that it had not rallied as it had been in the habit of doing for weeks, as soon as the pressure of the particular selling that had depressed it eased up. This had indicated that the line of least resistance was upward and it had cost me a million to shut my eyes to it. 17.15

Now, however, the reason that had made me cover at a big loss was no longer a good reason since there had not been the usual prompt and vigorous rally. So I sold 10,000 bales and waited. Pretty soon the market went off 50 points. I waited a little while longer. There was no rally. I had got pretty hungry by now, so I went into the dining-room and ordered my luncheon. Before the waiter could serve it, I jumped up, went to the broker’s office, I saw that there had been no rally and so I sold 10,000 bales more. I waited a little and had the pleasure of seeing the price decline 40 points more. That showed me I was trading correctly so I returned to the dining-room, ate my luncheon and went back to the broker’s. There was no rally in cotton that day. That very night I left Hot Springs.

It was all very well to play golf but I had been wrong in cotton in selling when I did and in covering when I did. So I simply had to get back on the job and be where I could trade in comfort. The way the market took my first ten thousand bales made me sell the second ten thousand, and the way the market took the second made me certain the turn had come. It was the difference in behaviour.

Well, I reached Washington and went to my brokers’ office there, which was in charge of my old friend Tucker. While I was there the market went down some more. I was more confident of being right now than I had been of being wrong before. So I sold 40,000 bales and the market went off 75 points. It showed that there was no support there. That night the market closed still lower. The old buying power was plainly gone. There was no telling at what level that power would again develop, but I felt confident of the wisdom of my position. The next morning I left Washington for New York by motor. There was no need to hurry.

When we got to Philadelphia I drove to a broker’s office. I saw that there was the very dickens to pay in the cotton market. Prices had broken badly and there was a small-sized panic on. I didn’t wait to get to New York. I called up my brokers on the long distance and I covered my shorts. As soon as I got my reports and found that I had practically made up my previous loss, I motored on to New York without having to stop en route to see any more quotations.

Some friends who were with me in Hot Springs talk to this day of the way I jumped up from the luncheon table to sell that second lot of 10,000 bales. But again that clearly was not a hunch. It was an impulse that came from the conviction that the time to sell cotton had now come, however great my previous mistake had been. I had to take advantage of it. It was my chance. The subconscious mind probably went on working, reaching conclusions for me. The decision to sell in Washington was the result of my observation. My years of experience in trading told me that the line of least resistance had changed from up to down.

I bore the cotton market no grudge for taking a million dollars out of me and I did not hate myself for making a mistake of that calibre any more than I felt proud for covering in Philadelphia and making up my loss. My trading mind concerns itself with trading problems and I think I am justified in asserting that I made up my first loss because I had the experience and the memory.

ENDNOTES

1 “Livermore Before Senate Committee,”

Boston Daily Globe, December 22, 1923, 5.

2 Edwin Lefevre, “Stock Manipulation,”

Saturday Evening Post, March 20, 1909, 32.

3 Charles M. Goodsell,

The Manual of Statistics (1914), 851.

4 Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz,

A Monetary History of the United States 1867

-1960 (1963), 232.

5 Robert Sobel,

The Big Board. (1965), 224.

7 Peter Wyckoff,

Wall Street and the Stock Markets (1972), 63.

8 “Wall Street News,”

Los Angeles Times, April 24, 1923, I12.

9 “Livermore Is to Re-Enter Market,”

Christian Science Monitor, October 10, 1923, 12.

10 W. P. Hamilton,

The Stock Market Barometer (1922), 63-65.

11 Richard Wyckoff,

Wall Street Ventures and Adventures through Forty Years (1930), 254.

12 Federal Trade Commission, “Report of the Federal Trade Comission on Methods and Operations of Grain Exporters, Volume 1,” May 16, 1922, 14.

13 Michael Steinhardt,

No Bull: My Life in and out of Markets (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2001).

14 Alexander D. Noyes,

The War Period of American Finance (1926), 435.

16 “Wheat Liquidation Causes Heavy Drop,”

New York Times, June 21, 1923, 29.

17 Mira Wilkins,

The History of Foreign Investment in the United States to 1914 (1989), 255.

18 American Iron and Steel Institute,

Directory of the Iron and Steel Works of the United States and Canada (1916), 111-112.

19 Charley Hannagan, “Will Bankruptcy Give Crucible Materials Corp. Enough Breathing Room?”

The Post-Standard, May 7, 2009.

20 Kevin Hillstrom and Laurie Collier Hillstrom,

Industrial Revolution in America, vol. 1 (2005), 73-75.

21 “Business & Finance: Catalyst in Steel,”

Time, December 30, 1929.

22 Robert Sobel,

The Big Board. (1965), 231.

24 “Excited Trading in Gold Mine Stock,”

New York Times, July 9, 1925, 32.

25 “Livermore Makes Curb Market Gasp,”

Boston Daily Globe, April 7, 1922, 19.