XIX

I do not know when or by whom the word “manipulation” was first used in connection with what really are no more than common merchandising processes applied to the sale in bulk of securities on the Stock Exchange. Rigging the market to facilitate cheap purchases of a stock which it is desired to accumulate is also manipulation. But it is different. It may not be necessary to stoop to illegal practices, but it would be difficult to avoid doing what some would think illegitimate. How are you going to buy a big block of a stock in a bull market without putting up the price on yourself? That would be the problem. How can it be solved? It depends upon so many things that you can’t give a general solution unless you say: possibly by means of very adroit manipulation. For instance? Well, it would depend upon conditions. You can’t give any closer answer than that.

I am profoundly interested in all phases of my business, and of course I learn from the experience of others as well as from my own. But it is very difficult to learn how to manipulate stocks to-day from such yarns as are told of an afternoon in the brokers’ offices after the close. Most of the tricks, devices and expedients of bygone days are obsolete and futile; or illegal and impracticable. Stock Exchange rules and conditions have changed,

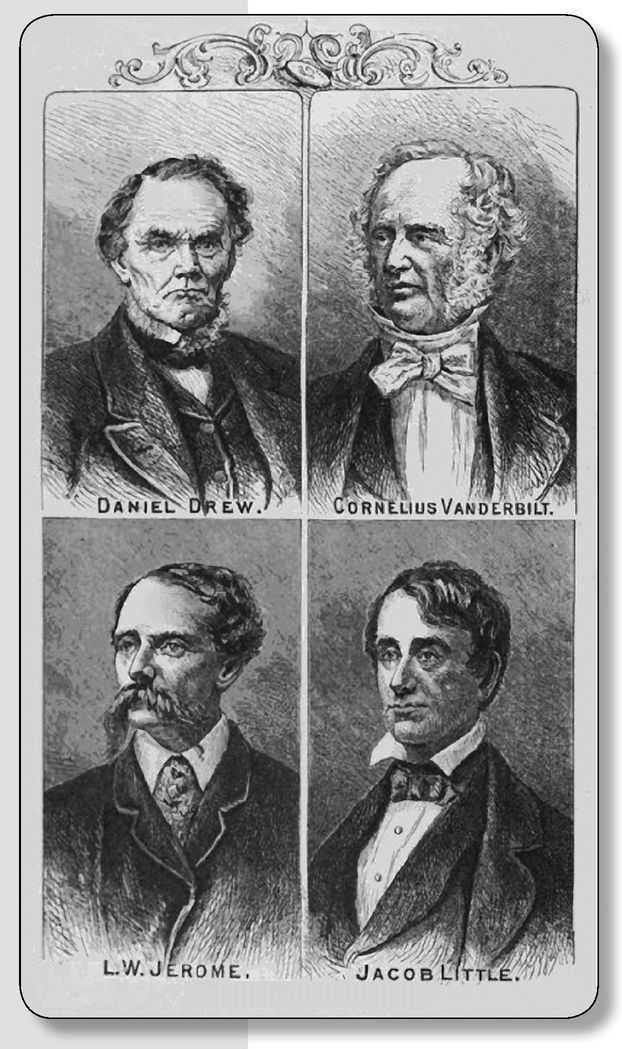

and the story—even the accurately detailed story—of what Daniel Drew or Jacob Little

or Jay Gould could do fifty or seventy-five years ago is scarcely worth listening to. The manipulator to-day has no more need to consider what they did and how they did it than a cadet at West Point need study archery as practiced by the ancients in order to increase his working knowledge of ballistics.

19.1In the 1800s and early 1900s, securities law did not offer investors much security and there was not much law. Most states required railroad securities to be registered starting in the 1850s, but rules were loose and fraud was rampant. By the late 1890s, states began to clamp down on sales of worthless securities in dubious gold mines, oil wells, and elixir makers that were said to promise “blue skies” but had no real assets.

By the mid-1910s, the time frame of this chapter, Midwestern states, led by Kansas and its pioneering banking commissioner, Joseph Norman Dolley, went a step further in barring the sale of securities of companies whose business was unfair, unjust, inequitable, or oppressive, or did not promise a fair return. The new statutes required registration of new securities and securities salespeople. New issues of shares also had to be accompanied by detailed financial statements. Government officials would have final say on which securities could be offered to the public.

1The state laws were challenged on constitutional grounds, as business owners complained that the rules lacked enough definition, usurped federal government authority, and amounted to an unfair hurdle to capital formation. The first major case, Hall v. Geiger-Jones Co., was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1917. The opinion, written by Justice Joseph McKenna, stated in part, “The prevention of deception is within the competency of government.”

2Most of the modern regulatory system as we recognize it today was created in the 1930s and 1940s following the 1929 stock market crash, putting an end to the law of the jungle that prevailed in the earliest years of Livermore’s campaigns.

19.2 The first “Great Bear of Wall Street,”

Jacob Little, had nothing when he first arrived in New York in 1817 at age 20 from his hometown of Newburyport, Massachusetts. The son of a shipbuilder used his guile to win an apprenticeship with Jacob Barker, then the largest banker in New York, from 1817 to 1822. He eventually left banking to trade securities on his own, and became a member of an early form of the New York Stock Exchange. After opening his small office in a Wall Street basement, he became known for hard work and keen business insight. Historian Matthew Hale Smith wrote: “Caution, self-reliance, integrity, and a far-sightedness beyond his years, marked his early career. For 12 years he worked in his little den as few men work. His ambition was to hold the foremost place on Wall Street. Eighteen hours a day he devoted to business—twelve hours to his office.”

3

his peak years, 1838 to 1846. Said one biographer: “He would reign the king of the market, fight a dozen pitched battles, suffer defeat, abdicate, and then once more ascend the throne, all in the space of six months.”

4 Finally, Little failed for good during the Civil War, says his biographer, when he “remained a bear on the rising tide of currency inflation following the outbreak of the war, and was submerged and wiped out.”

5 Little is credited with inventing the “manipulated short sale”—selling short and flloating rumors of the company’s financial woes.

6 He also claimed to be the inventor of the convertible bond, which he used to great effect to break Daniel Drew’s attempt to corner him in Erie stock in 1855. Reported a journalist three decades later:

He had sold large blocks of Erie, seller’s option, at six and twelve months. The “happy family,” composed of the most eminent members of the board, combined against him. The day of settlement came, Erie shares had been run up to a high figure. At 2 p.m. the brokers prophesied that the Napoleon of finance would meet his Waterloo. At 1 p.m. he stepped into the Erie office, presented a mass of convertible bonds that he had quietly purchased in England, and demanded the instantaneous exchange of share equivalents for them. The requisition was met. Little returned to his office, fulfilled his contracts, broke the corner, and was Wellington and Napoleon in one. The convertibles were his Blucher and night.

7A “Blucher” is a bid to win all the tricks in a hand of a British card game called Napoleon, and that was an appropriate reference because Little was described by a biographer as a “master of every kind of game played in stocks, rings, corners, sleight-of-hand, beggar your neighbor, bluff, lock-up and bar-out, straddling two horses going different ways, he had the skill as well as the nerve to play them all, and for the most part came out the winner.”

8The beginning of the end for Little came in the run-up to the Panic of 1857, which resulted from a credit bubble following the discovery of gold in California. Paper money in circulation doubled between 1849 and 1857 on the promise of new gold coin. But a trade deficit with Europe sent the gold away, so bankers withdrew currency, and trade and speculation collapsed. Little was short 100,000 shares of Erie, expecting a crash, but a last advance before the decline overextended him. He lost his position and failed for want of $10 million on December 5, 1856.

9Little died poor on March 28, 1865, leaving a widow but no children.

10 He once said: “I care more for the game than the results, and, winning or losing, I like to be in it!”

11 This energy was on display in his latter years, as described by William Fowler:

Still clinging to the objects of a pursuit which was to him a passion, his face bearing the marks of the fierce struggles of his life, a broken weird looking old man, he haunted the Board Room [in the New York Stock Exchange] like a spectre where he had once reigned as a king, offering small lots of shares of the same stock, the whole capital whereof he had once controlled. Where then were the piled millions which that cunning hand and scheming brain had rolled up? Where the prestige of his victories on ‘change? Gone, scattered, lost. Poor and unnoticed, he passed away from the scene, and left nothing behind him but the shadow of what was once a

great Wall Street reputation.

12On the other hand there is profit in studying the human factors—the ease with which human beings believe what it pleases them to believe; and how they allow themselves—indeed, urge themselves—to be influenced by their cupidity or by the dollar-cost of the average man’s carelessness. Fear and hope remain the same; therefore the study of the psychology of speculators is as valuable as it ever was. Weapons change, but strategy remains strategy, on the New York Stock Exchange as on the battlefield. I think the clearest summing up of the whole thing was expressed by Thomas F. Woodlock

when he declared: “The principles of successful stock speculation are based on the supposition that people will continue in the future to make the mistakes that they have made in the past.”

In booms, which is when the public is in the market in the greatest numbers, there is never any need of subtlety, so there is no sense of wasting time discussing either manipulation or speculation during such times; it would be like trying to find the difference in raindrops that are falling synchronously on the same roof across the street. The sucker has always tried to get something for nothing, and the appeal in all booms is always frankly to the gambling instinct aroused by cupidity and spurred by a pervasive prosperity. People who look for easy money invariably pay for the privilege of proving conclusively that it cannot be found on this sordid earth. At first, when I listened to the accounts of old-time deals and devices I used to think that people were more gullible in the 1860’s and ’70’s than in the 1900’s. But I was sure to read in the newspapers that very day or the next something about the latest Ponzi

or the bust-up of some bucketing broker and about the millions of sucker money gone to join the silent majority of vanished savings.

19.3 Born in Ireland in 1866, Thomas Woodlock was “one of the leading financial writers of this country, and he had held that position for half a century,” according to the New York Times.

13,

14 He was editor of the Wall Street Journal from 1902 to 1905 and a columnist at the paper from 1930 until his death in 1945. At the age of 28, he wrote The Anatomy of a Railroad Report, a book meant to help investors who do not “take the trouble to make themselves acquainted with the actual condition of their property… obtain a clear idea of the state of his investment, for great and important changes in railroad conditions are in progress.”

15

Woodlock worked as a broker in both London and New York. He was a member of the U.S. Interstate Commerce Commission and active in the Catholic Church. His morality, depth of knowledge, and command of history impressed his peers. According to the Times, “He might illustrate a point in economics by quoting some thirteenth-century pope, or some scrap of wisdom from some obscure figure in the eighteenth century.”

1619.4 Charles Ponzi’s scheme in 1919-1920 to defraud gullible Bostonians was so extreme that his name has entered the English lexicon. Ponzi’s promise was to pay investors 50% returns in 45 days through investment in international reply coupons (IRCs).

17 The coupons were created in 1906 to facilitate global shipping by the Universal Postal Union, and were redeemable into country-specific postage. Ponzi claimed that by arbitraging postage rate—buying IRCs cheaply and exchanging them for more expensive stamps in other countries—he could provide unbelievable returns. In reality he was merely paying old investors the proceeds from new deposits. The scam collapsed after being exposed in a Pulitzer Prize-winning series by the Boston Post in August 1920. Ponzi served 10 years in prison before being deported to Italy; he died blind and poor in Brazil in 1949.

A similar scheme ruined ex-President Ulysses S. Grant in the 1880s after he partnered with his son and a speculator named Ferdinand Ward, who was said to have “a born genius for evil.”

18 Ward befriended Grant’s son, and together they persuaded the former Civil War general to lend his credibility to create a brokerage called Grant & Ward in 1883.

19 The brokerage took investors’ money but never actually invested it, paying out new deposits to old customers as dividends. The scheme collapsed on May 9, 1884, after the fi rm overdrew its account at the Marine National Bank, causing both companies to fail. A week later, a second wave of bank failures led to the Panic of 1884. Ward served 6 years in prison.

20 Grant’s fam ily was left destitute until the tarnished hero’s memoirs earned a fortune a few years later.

19.5 These were cons in which bucket shop operators would place legitimate orders on the actual exchanges to move the price of underlying stocks against the positions of their patrons. They were an example of the adversarial relationship between bucket shops and their customers. In contrast, legitimate brokers benefi ted from their customers’ good fortune through larger trades and more commissions. In 1895 and again in 1900, the Chicago Board of Trade launched investigations into its members’ telegraph wire connections. During the crackdown, 6 members were expelled and 13 were suspended. Fearful of further investigations, other brokers soon refused to fi ll orders from bucket shop owners.

21 When I first came to New York there was a great fuss made about wash sales

and matched orders, for all that such practices were forbidden by the Stock Exchange. At times the washing was too crude to deceive anyone. The brokers had no hesitation in saying that “the laundry was active” whenever anybody tried to wash up some stock or other, and, as I have said before, more than once they had what were frankly referred to as “bucket-shop drives,” when a stock was offered down two or three points in a jiffy just to establish the decline on the tape and wipe up the myriad shoe-string traders who were long of the stock in the bucket shops. As for matched orders, they were always used with some misgivings by reason of the difficulty of coördinating and synchronising operations by brokers, all such business being against Stock Exchange rules. A few years ago a famous operator canceled the selling but not the buying part of his matched orders, and the result was that an innocent broker ran up the price twenty-five points or so in a few minutes, only to see it break with equal celerity as soon as his buying ceased. The original intention was to create an appearance of activity. Bad business, playing with such unreliable weapons. You see, you can’t take your best brokers into your confidence—not if you want them to remain members of the New York Stock Exchange. Then also, the taxes have made all practices involving fictitious transactions much more expensive than they used to be in the old times.

The dictionary definition of manipulation includes corners. Now, a corner might be the result of manipulation or it might be the result of competitive buying, as, for instance, the Northern Pacific corner on May 9, 1901, which certainly was not manipulation. The Stutz corner

was expensive to everybody concerned, both in money and in prestige. And it was not a deliberately engineered corner, at that.

Renowned for speedy oppearance as well as performance, this 1915 Stutz Bearcat was one of the most popular sport modeb of its day.

19.6 In 1920, Thomas F. Ryan cornered the stock of the Stutz Motor Car Co.—the last great corner on the New York Stock Exchange, which historian Robert Sobel calls “a forerunner of the Livermore and Cutten operations of a few years later.”

22 Stutz was a maker of legendary sports cars, such as the 1915 Bearcat. Ryan was one of its largest investors.

Thomas’s father, Allan A. Ryan, had turned over his NYSE seat to his son at the age of 25. The young man became known to contemporaries as a “powerful and clever bull operator” with a talent for squeezing short sellers. For the most part, the wind was at his back: There was an explosive bull market in 1919 after the armistice that ended World War I was signed. In response, the Federal Reserve issued a warning about what it called the “speculative tendency of the times.”

23The mood was subdued in 1920, which makes Ryan’s achievement all the more impressive. Prohibition had started. Interest rates were on the rise. Anarchists exploded a deadly bomb outside the offices of J .P. Morgan & Co. By the end of the year, prices on the NYSE were 33% below their April peak.

Stutz was in excellent business shape when its stock started rising from $100 a share in January to more than $134 on February 2. Ryan was told that short sellers, many of whom were leading members of the NYSE, were readying a bear raid. Observer John Brooks describes Ryan’s predicament, since many of the bears were acquaintances:

In the course of making a killing in Stutz they might maim the company and separate Ryan from much of his fortune—or, contrariwise, their maneuver might end up costing them their own shirt—but in either case the antagonists would be supposed to take it all in good part and continue the joking and bantering during the contest and after it. Such was the code.

24Ryan, who was sick in bed with pneumonia, returned to Wall Street with nurse in tow to do battle. His goal was to buy all the stock offered for sale at increasing prices to squeeze the shorts. This, of course, required lots of cash. Ryan turned to banks and friends, putting up his family’s possessions as collateral. In early March, things looked bleak for Ryan as Stutz dropped back to $100. He persevered, at risk of losing his wife’s furs, and by March 24, the price was up to $282. By the end of the week it was at $391. Other shareholders took advantage of the rise to capture profits, but Ryan kept buying.

More short sellers descended. They would borrow shares from Ryan before selling them back to him since, according to a historian, “there was no longer anyone else who had any.”

25 Slowly, as shares became scarce, the bears realized they had been overpowered. They could either pay an exorbitant sum to buy shares back from Ryan to settle their loan of stock certificates, or they could go to jail. The corner was in effect.

Instead, the bears chose a third way. Using their committee positions on the NYSE, they summoned Ryan to explain the gyrations in Stutz. After telling them matter-of-factly that he owned more shares than were in existence, he demanded $750 per share to settle. The NYSE insiders then threatened to throw Ryan out of the exchange. Ryan was defiant: His offer rose to $1,000 per share. The exchange responded by voiding Ryan’s contracts and de-listing Stutz shares. He resigned from his seat and published the names of some of the short sellers in the New York World. Confidence in the integrity of the exchange waned, and there was talk of increased government regulation.

In the end, the NYSE blinked and the shorts were settled at $550 per share. It was a Pyrrhic victory for Ryan. Since the exchange had delisted Stutz, there was no market for Ryan to sell into. To make matters worse, the bears were mad with desire for revenge and started raiding Ryan’s other holdings. And bankers were closing in as well. On July 21, 1922, Ryan filed for bankruptcy, listing debts of over $32 million and assets of $643,533. Stutz Motors stock was sold at public auction for $20 a share. The company eventually failed in 1937. Ryan never recovered and died in 1940.

19.7 Cornelius Vanderbilt was born in 1794 into a Staten Island farming family that sailed its produce to market in Manhattan. After earning a small sum from his mother for fieldwork, Vanderbilt bought himself a two-masted, flat-bottomed sail-boat with which he carried passengers and freight across the bay. Two years later, during the War of 1812, Vanderbilt was awarded a U.S. Army contract to supply posts around New York. Later, with the advent of the steamship, Vanderbilt sold his military supply business interests and became the captain of another man’s steamer.

From this inauspicious start, Vanderbilt built a vast empire of riverboats, steamships, and railroads. He dominated shipping routes up and down the Atlantic seaboard, to Europe, and to California. In fact, it is said that he moved more men to the gold fields of California than anyone else. Sobel describes him:

The Commodore was tall and aristocratic….He had a large nose, piercing eyes, and an expression of utter contempt on his face that frightened friends as well as enemies. When he spoke a stream of colorful, profane language would emerge from imperious lips.… He was not the sort of man that one crossed twice.

Yet that is exactly what Daniel Drew and his associates did on several occasions. In the aftermath of the Erie shenanigans described earlier, Vanderbilt sent the local sheriff to arrest Drew, Fisk, and Gould. The men caught wind of this and, with the Erie’s ledgers and $8 million from its treasury, sailed through the fog to New Jersey, where they barricaded themselves in the lobby of a hotel. Fisk hired gangs of men for protection, ultimately organizing a ramshackle navy of rowboats bristling with rifles. Twelve-pound cannons were mounted on a dock. A sensational display of political corruption ensued as the two sides battled to win over judges and legislators.

Eventually, Vanderbilt wrote to his old foe and occasional ally: “Drew: I’m sick of the whole damned business. Come and see me. Vanderbilt.”

26 Drew was sympathetic. He did not care for New Jersey or for the antics of Gould and Fisk. The two men met and reminisced about their old days on the river. A peace was forged: The Erie treasury would buy the illegitimate shares sold to Vanderbilt.

OF WALL STREET

As a matter of fact very few of the great corners were profitable to the engineers of them. Both Commodore Vanderbilt’s

Harlem corners paid big, but the old chap deserved the millions he made out of a lot of short sports, crooked legislators and aldermen who tried to double-cross him.

On the other hand, Jay Gould lost in his Northwestern corner.

Deacon S. V. White made a million in his Lackawanna corner, but Jim Keene dropped a million

in the Hannibal & St. Joe deal. The financial success of a corner of course depends upon the marketing of the accumulated holdings at higher than cost, and the short interest has to be of some magnitude for that to happen easily.

I used to wonder why corners were so popular among the big operators of a half-century ago. They were men of ability and experience, wide-awake and not prone to childlike trust in the philanthropy of their fellow traders. Yet they used to get stung with an astonishing frequency. A wise old broker told me that all the big operators of the ’60’s and ’70’s had one ambition, and that was to work a corner. In many cases this was the offspring of vanity; in others, of the desire for revenge. At all events, to be pointed out as the man who had successfully cornered this or the other stock was in reality recognition of brains, boldness and boodle. It gave the cornerer the right to be haughty. He accepted the plaudits of his fellows as fully earned. It was more than the prospective money profit that prompted the engineers of corners to do their damnedest. It was the vanity complex asserting itself among cold-blooded operators.

Dog certainly ate dog in those days with relish and ease. I think I told you before that I have managed to escape being squeezed more than once, not because of the possession of a mysterious ticker-sense but because I can generally tell the moment the character of the buying in the stock makes it imprudent for me to be short of it. This I do by common-sense tests, which must have been tried in the old times also. Old Daniel Drew used to squeeze the boys with some frequency and make them pay high prices for the Erie “sheers” 19.11 they had sold short to him. He was himself squeezed by Commodore Vanderbilt in Erie, and when old Drew begged for mercy the Commodore grimly quoted the Great Bear’s own deathless distich:

He that sells what isn’t hisn

Must buy it back or go to prisn.

19.8 The most famous example of this occurred when Vanderbilt returned from a trip to Europe to find that the Nicaragua Transit Co., to which he had turned over his shipping trade in Nicaragua, had “failed to give him what he thought should be a proper accounting.”

27 Vanderbilt wrote one of the few letters he ever sent in his own hand. It was barely legible but the message was clear. It read: “Gentlemen: You have undertaken to cheat me. I won’t sue you, for the law is too slow. I will ruin you. Yours truly, Cornelius Vanderbilt.”

28 Within two years, the company was gone.

19.9In 1872, Gould and two collaborators successfully bid up the shares of Chicago & NorthWestern Railroad from $95 to $230 over a two-day period—yet they were reported to have made nothing from the advance.

29 Henry Clews says the rise went from $80 to $280 before falling back to $80 again, in the process “pretty near crushing” Gould “in spite of his incomparable capacity for wriggling out of a tight place.”

30

19.10 In 1881, just after President Garfield had been shot, a corner attempt was made in Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad shares. The line ran from Hannibal, Missouri, on the Mississippi River to St. Joseph on the Kansas River. After a marked decline in revenue, the company was suffering financial distress. Dividends on common shares amounted to only 1.5%. Like vultures scouting a meal, short sellers began to descend. Meanwhile, the firm’s vice president had left the city and given his broker, William Hutchinson, written instructions to use discretion when managing his large fortune.

Hutchinson started to buy all the stock the bears would sell. On Monday, September 5, the price moved over $97. The following day, the situation became clear as the shorts tried to cover and the price of Hannibal & St. Joe soared to close at $137. On Wednesday, the price reached $200.

Luckily for the bears, Thursday was a holiday: The New York governor had called for a day of prayer to help President Garfield recover from his wounds. (He died a few days later.) A break in the action allowed shorts to plot an exit strategy. On Friday, the company’s president, William Dowd, was accused of conspiracy to corner the stock by an operative of the bear pool. Meanwhile, the price continued to rise and peaked at $350 a week later.

In the end, the accusation was settled out of court. It turned out that Hutchinson was surreptiously making side bets for himself on the short side and was using his position to ensure the price sank as the shorts settled. When that was uncovered, he was expelled from the exchange for what observers called “obvious fraud.”

3119.11 Many of the great business tycoons and speculators of this time lacked a formal education. Drew came from a modest background but possessed what Henry Clews called a steadfast ability to attain “great success by stubbornly following up one idea, and one line of thought and purpose.”

32 Clews said of both Drew and Vanderbilt:

Everybody who knew these two men were of the opinion that with a fair or liberal education they would never have cut a prominent figure as financiers.… Perhaps it might have been impossible for any teacher to make Drew pronounce the word shares otherwise than “sheers.” Or convince Vanderbilt that the part of a locomotive in which steam is generated should not be spelt phonetically, “boylar.”

33CELEBRITIES OF WALL STREET.

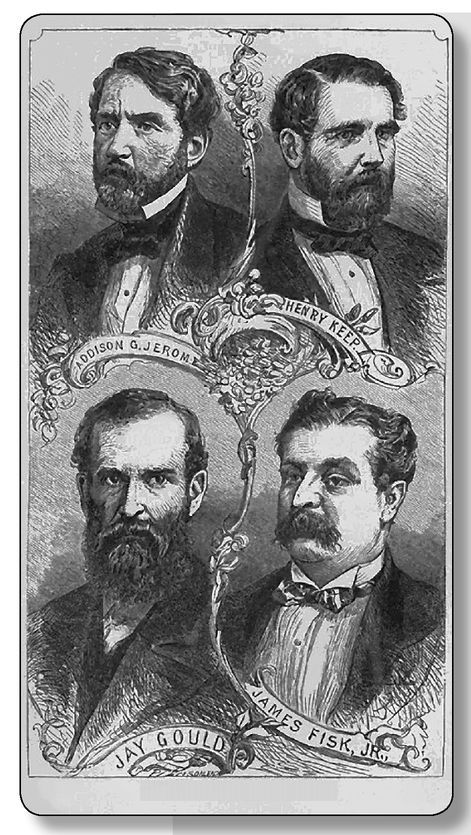

19.12Addison and his eight siblings were collectively known as the Jerome Brothers. Speculation ran in their genes. Leonard Jerome was a partner with William Travers in the brokerage house Travers & Jerome and had previously been appointed consul to the Austrian Empire by President Millard Fillmore. Jerome and Travers were successful on the short side of the market. Another brother, while studying theology at Princeton, “took a flier in the memorable mulberry tree speculation and made $40,000,”

34 according to the New York Times.

Addison got his start in the dry goods business before he amassed a fortune and earned a reputation as “the Napoleon of the Open Board” in 1863 through a series of speculative exploits.

35 He was worth $3 million after successfully cornering four railroad stocks but lost it all in an attempt to manipulate the Old Southern, ending his nine-month reign. At the time, the Open Board was a major competitor to the New York Stock Exchange. The two institutions were merged in 1869 in the wake of the Erie War.

Addison was a “middle-sized, quiet-looking man, with a bluish gray eye, and a slight stoop,” according to William Fowler’s excellent Ten Years in Wall Street. He was a big operator who inspired confidence in observers and was watched closely for clues during the Open Board’s stock auctions. Fowler holds Jerome’s achievements during the spring and summer of 1863 in high regard, labeling him a “bull-leader.” He defines the term at length in a way that could be applied in any era:

Wall Street, considered as an aggregation of human-forces and money-forces, without bull-leaders, would be a flock of sheep without a bell-wether, a mob without a spokesman, an army without a commander. It is the bull-leader who organizes and compacts those forces, brings them under his banner and leads them to victory or—ruin.

36And ruin was where Jerome ended. Clews wrote that Jerome “displayed great ability in the conduct of speculative campaigns, but he went beyond his depth and the end was financial shipwreck.”

37 19.13 Called

“William the Silent” in an homage to rebel sixteenth-century Dutch nobleman William I, Prince of Orange, who earned the nickname for his quiet circumspection, Keep rose to prominence after being born in a poorhouse and running away from his foster parents as a youth. He never returned to them, and instead made a living by gathering Canadian currency for 20 cents in the United States and running it north to collect 25 cents. Eventually, he opened an exchange office in a small town and eloped with the daughter of a townsman who had sworn to shoot him.

38

Keep was the first to master the blind pool, in which several speculators would provide capital to manage a corner and would share in the profits or losses proportionally. Keep was so trusted that participants often accepted unfavorable terms. Said one historian: “So as to prevent any one member from using information gained during the meetings to secretly work against his fellows at the market, no one was to know when the stock would be bought or sold, how the corner would be accomplished, or even which stock was chosen for the manipulation.”

39At the peak of his influence, Keep could raise $1 million in a week. One participant netted over $2 million through a $100,000 investment. At one point, the Michigan Southern & Northern Indiana Railroad, nicknamed “Old Southern,” became his favorite stock. Fowler recalls watching Keep snap up shares:

I remember, in the spring of 1863, seeing him stand behind his broker in the street-crowd and pull his coat-tail, as a signal to buy. His broker after buying one thousand shares of Old Southern stopped, when he felt his coat-tail jerked again, violently, and he commenced buying until after seven successive jerks he had bought eight thousand shares, all for the account of the quiet man in the rear, who thereupon relaxed his grasp, and retired to his office without saying a word. He believed in the proverb, “Speech is silver; silence is golden.”

40Keep eventually ascended to a directorship at Old Southern. When Jerome launched his corner attempt, Keep turned bearish and authorized the issuance of 14,000 shares of stock. He planned to use the high prices to enrich his company’s treasury as well as his own pocket. To ensure success, Keep borrowed shares from the Jerome ring and sold into the market—creating the illusion of a rising and vulnerable short interest. When the U.S. Treasury borrowed $35 million from Wall Street in September 1863, monetary conditions tightened and stocks began to fall. The trap was set. Keep used all 14,000 shares to repay borrowed stock, and Fowler said, “Old Southern came down like an avalanche.”

41Jerome lost his fortune and died of a heart attack in 1864. Keep died wealthy in 1869, leaving his family $4.5 million. He once told a friend:

Would you like to know how I made my money? I did it by cooping the chickens; I did not wait till the whole brood was hatched. I caught the first little chicken that chipped the shell, and put it in the coop. I then went after more. If there were no more chickens, I had one safe at least. I never despised small gains. What I earned, I took care of. I never periled what I had, for the sake of grasping what I had not secured.

42Wall Street remembers very little of an operator who for more than a generation was one of its Titans. His chief claim to immortality seems to be the phrase “watering stock.”

Addison G. Jerome

was the acknowledged king of the Public Board in the spring of 1863. His market tips, they tell me, were considered as good as cash in bank. From all accounts he was a great trader and made millions. He was liberal to the point of extravagance and had a great following in the Street—until Henry Keep,

known as William the Silent, squeezed him out of all his millions in the Old Southern corner. Keep, by the way, was the brother-in-law of Gov. Roswell P. Flower.

19.14 The New York & Harlem Railroad was chartered in 1831 and never grew more than 132 miles long. It possessed one great asset: the right of direct access to the east side of Manhattan. The line constructed its railway from Harlem to lower Manhattan through what would become Park Avenue. At first, passengers in open carriages were pulled by horse teams. Later, as it expanded, the Harlem decided on an inland route to avoid antagonizing the powerful steamboat interests on the Hudson.

Financial difficulties befell the Harlem in the early 1860s. It canceled its dividend payment, and its shares tumbled to just $9. In 1862, Vanderbilt accumulated 55,000 shares with an idea of improving the railroad and reaping a profit. Clews notes that this came 30 years after Vanderbilt originally had been asked to join the railroad, to which he had responded: “I’m a steamboat man, a competitor of these steam contrivances that you tell us will run on dry land. Go ahead. I wish you well, but I never shall have anything to do with ‘em.”

43Vanderbilt pushed for a new streetcar line franchise for Harlem from the Common Council of the City of New York of which Daniel Drew was a member. Harboring resentment from their prior battles, Drew conspired to sell Harlem short, bribe his fellow council members to vote against Vanderbilt, and watch as Harlem’s anticipatory rise was reversed.

On June 25, the council denied the Harlem’s request. Shares fell from $110 to $72. But Vanderbilt and his allies continued to buy. Imagine Drew’s surprise as the Harlem leveled off and began slowly to rise.

44 Prices continued to advance past $150 as the shorts started to sweat. Vanderbilt eventually settled with the shorts at $180 a share—a loss to Drew of $70 a share. Besides the monetary reward and the satisfaction for foiling an old adversary, Vanderbilt had gained control of his first railroad.

Later in 1864, the same thing happened again when the New York state legislature was discussing whether to allow Vanderbilt to merge the Harlem and the Hudson River Railroad. It occurred to some of the legislators that there was money to be made by selling Harlem short and then defeating the measure. Drew had had the same idea.”

45 The politicians mortgaged their houses and properties to get money to sell Harlem short. It was, according to Clews, an example of the old maxim, “Whom the gods devote to destruction, they first make mad.”

46Later, after he defeated the bears in the same manner as before, Vanderbilt remarked that he had “busted the whole legislature, and scores of the honorable members had to go home without paying their board bills.”

47In most of the old corners the manipulation consisted chiefly of not letting the other man know that you were cornering the stock which he was variously invited to sell short. It therefore was aimed chiefly at fellow professionals, for the general public does not take kindly to the short side of the account. The reasons that prompted these wise professionals to put out short lines in such stocks were pretty much the same as prompts them to do the same thing to-day. Apart from the selling by faith-breaking politicians in the Harlem corner

of the Commodore, I gather from the stories I have read that the professional traders sold the stock because it was too high. And the reason they thought it was too high was that it never before had sold so high; and that made it too high to buy; and if it was too high to buy it was just right to sell. That sounds pretty modern, doesn’t it? They were thinking of the price, and the Commodore was thinking of the value! And so, for years afterwards, old-timers tell me that people used to say, “He went short of Harlem!” whenever they wished to describe abject poverty.

Many years ago I happened to be speaking to one of Jay Gould’s

old brokers. He assured me earnestly that Mr. Gould not only was a most unusual man—it was of him that old Daniel Drew shiveringly remarked, “His touch is Death!”—but that he was head and shoulders above all other manipulators past and present. He must have been a financial wizard indeed to have done what he did; there can be no question of that. Even at this distance I can see that he had an amazing knack for adapting himself to new conditions, and that is valuable in a trader. He varied his methods of attack and defense without a pang because he was more concerned with the manipulation of properties than with stock speculation. He manipulated for investment rather than for a market turn. He early saw that the big money was in owning the railroads instead of rigging their securities on the floor of the Stock Exchange. He utilised the stock market of course. But I suspect it was because that was the quickest and easiest way to quick and easy money and he needed many millions, just as old Collis P. Huntington

was always hard up because he always needed twenty or thirty millions more than the bankers were willing to lend him. Vision without money means heartaches; with money, it means achievement; and that means power; and that means money; and that means achievement; and so on, over and over and over.

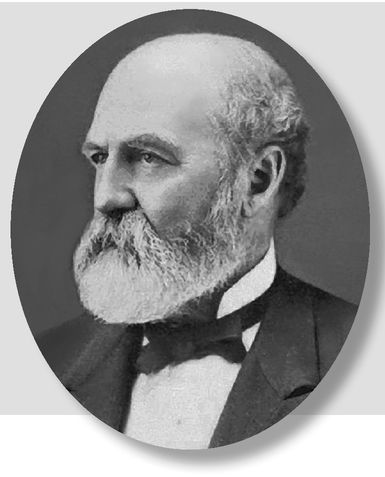

19.15 Of all the men mentioned in these pages, Jay Gould is probably the best example of a wild speculator on Wall Street during the Civil War era. Gould was born in 1836 into a poor dairy-farming family in upstate New York. His given name was Jason, but he liked Jay better. As a boy, Gould tended his father’s 20 cows barefoot, suffering from painful thistles. He saved some money, went to a local seminary school, and wrote an essay entitled “Honesty Is the Best Policy.”

Later, Gould worked in a country store and as a land surveyor. He got his break when he started selling his own maps and went to New York to try to sell a mousetrap he invented. There he befriended a local businessman with interests in tanneries. After the owner shot himself during the Panic of 1857, Gould hired a squad of several hundred men to storm the tannery and push out the other partner. For a while, Gould was strictly a leather merchant. But soon he started dabbling in Wall Street via a little brokerage business.

Naturally, that meant an interest in railroads, which eventually led to an association with Daniel Drew and his broker Jim Fisk. By 1867, both Gould and Fisk joined Drew on the board of the Erie Railroad. All the pieces were in place for Gould to embark on his most famous exploits, which included the Black Friday gold corner attempt and the Erie War against Vanderbilt.

Called the “Wizard of Wall Street,” Gould was a man of great contrasts. On the outside, he was a timid, short, frail, and sickly man who rarely looked anyone in the eye and was rather effeminate. On the inside, he was a ruthless, smart, cold-blooded predator who would extract his profit with indifference from friend or foe. What his physique lacked, his intellect and spirit provided in abundance: He was endowed with a rare “courage, grit, insight, foresight, tireless energy, and indomitable will,”

48 according to a biographer.

Meade Minnigerode writes of Gould’s public persona:

“He played the great game of speculative finance for all it could be made to yield without disguise or apology—a stranger to honesty and good faith; a personality of alarming cunning deprived of all feeling, scornful of any consideration or rectitude. An operator who always played with loaded dice; an administrator whose only interest lay in the accumulation of selfish profits; a genius whose talents were completely devoted to the limited spheres of his own enrichment; a parasite of disaster, an instrument of calamity, a destroyer.”

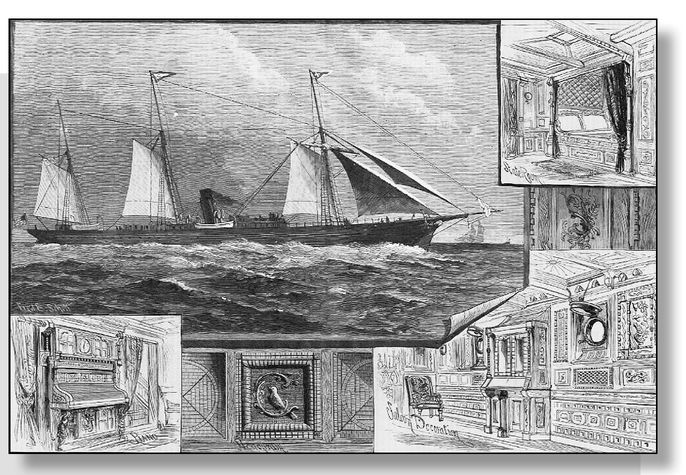

49Yet Gould was also a loving, charitable man to his inner circle. Jim Fisk’s wife wrote that Gould was the only friend who still responded to her after her husband’s death. Gould lived a clean life free of extravagance except for his private, luxuriously appointed railcar and his yacht Atalanta, shown above. He was a lover of flowers and a noted orchid collector. He was also a gifted writer, penning a 426-page history of his home entitled History of Delaware County before he was 20. A work based on Drew’s diary references Gould’s accomplishment:

Jay would do most of the writer-work. “Jay, you’re the ink slinger,” Jimmy [Fisk] would say to him, and would pull him up to the table and slap a pen in his hand. He would do it so rough that Jay, who is a slip of a man, would wince. … As I started to say, Jay has a high and noble way of stringing words together—a knack which I never could get.

50Here is a sample from the opening chapter of his book:

History with the more and more extensive meaning acquired by the advancement of civilization, by the diffusion of education, and by the elevation of the standard of human liberty, has expanded into a grand and beautiful science. It treats of man in all his social relations, whether civil, religious, or literary, in which he has had intercourse with his fellows. The study of history, to a free government like the one in which we live, is an indispensable requisite to the improvement and elevation of the human race. It leads us back through the ages that have succeeded each other in time past; it exhibits the condition of the human race at each respective period, and by following down its pages over the vast empires and mighty cities now engulfed in oblivion, but which the faithful historian presents in a living light before us, we are enabled profitably to compare and form a more correct appreciation of our own relative position.

51In 1874, Gould was sued and eventually forced from the Erie board by British shareholders who did not approve of his buccaneering ways. He agreed to return $6 million in company funds and retire provided all pending suits against him were dropped. His final days were plagued by dyspepsia and insomnia. On December 2, 1892, Gould died, leaving $72 million to his family. Said Minnigerode: “And when it was announced, the stocks of all his corporations rose in a rejoicing market.”

5219.16 Collis P. Huntington was one of the men responsible for building the Central Pacific Railroad, which joined with the Union Pacific at Promontory Summit in Utah to form the First Transcontinental Railroad. Afterward, Huntington would work with a number of other railroads, including the Southern Pacific and the Chesapeake & Ohio. Born in Connecticut in 1821, he sailed for San Francisco in 1849 and operated a general store out of a tent. Later, his business grew to be one of the most prosperous on the Pacific coast.

It was then that Huntington devised the idea for a railroad to the East. He went to Washington to lobby for the passage of the Pacifi c Railroad bill that provided land grants and monetary support to the constructors of the railway. However, during the construction of the fi rst 50 miles of Central Pacifi c track, funds ran dry, forcing Huntington and his associates to use their private wealth to keep 800 workers on the job and ensure the project’s success. Clews says that Huntington was “one of the few men in this country who have shown themselves more than a match for Jay Gould.”

53Of course manipulation was not confined to the great figures of those days. There were scores of minor manipulators. I remember a story an old broker told me about the manners and morals of the early ’60’s. He said:

“The earliest recollection I have of Wall Street is of my first visit to the financial district. My father had some business to attend to there and for some reason or other took me with him. We came down Broadway and I remember turning off at Wall Street. We walked down Wall and just as we came to Broad or, rather, Nassau Street, to the corner

19.17 Shylock is a fictional Jewish character from Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice. Shylock’s character lends money to his Christian rival Antonio and sets the price of the loan at a pound of his flesh. After Antonio goes bankrupt, Shylock demands his pound of flesh in revenge for Antonio’s previous insults against him.

Shylock’s image and name were commonly used to air anti-Semitic feelings during this period. A cartoon from 1840 shows a well-dressed Shylock grabbing a man by his throat and demanding “Pay me what thou owest” while his victim pleads for patience. The cartoon was drawn in protest of a failure by Congress to pass a national bankruptcy law.

where the Bankers’ Trust Company’s building now stands, I saw a crowd following two men. The first was walking eastward, trying to look unconcerned. He was followed by the other, a red-faced man who was wildly waving his hat with one hand and shaking the other fist in the air. He was yelling to beat the band: ‘Shylock! Shylock! What’s the price of money? Shylock! Shylock!’

I could see heads sticking out of windows. They didn’t have sky-scrapers in those days, but I was sure the second-and third-story rubbernecks would tumble out. My father asked what was the matter, and somebody answered something I didn’t hear. I was too busy keeping a death clutch on my father’s hand so that the jostling wouldn’t separate us. The crowd was growing, as street crowds do, and I wasn’t comfortable. Wild-eyed men came running down from Nassau Street and up from Broad as well as east and west on Wall Street. After we finally got out of the jam my father explained to me that the man who was shouting ‘Shylock!’ was So-and-So. I have forgotten the name, but he was the biggest operator in clique stocks in the city and was understood

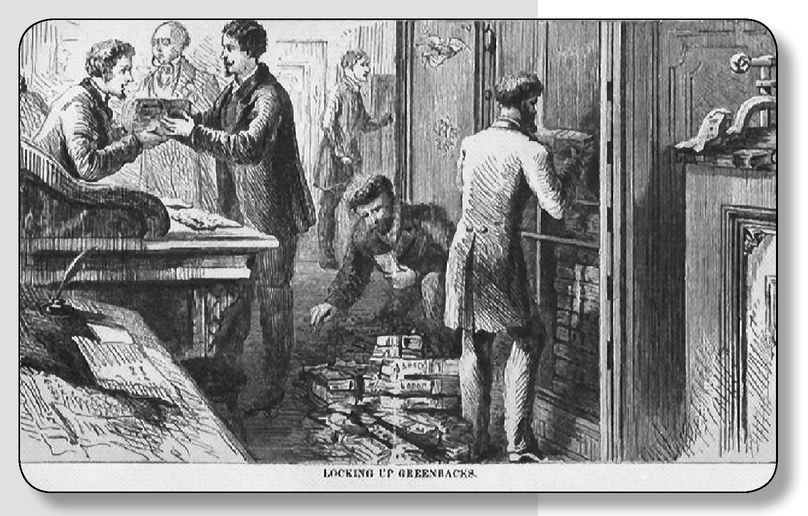

19.18 It is likely that this old broker, if he is indeed a real person, might be referring to the efforts of Daniel Drew, Jim Fisk, and Jay Gould to “constrict the money arteries by locking up greenbacks,”

54 In Fowler’s words. It worked like this: Checks for large amounts were drawn up from various banks by heavy depositors. The banks then certified the checks as good. Then the certified amount would be removed from the banks’ surplus fund reserve, as illustrated to the right.

Here is the kicker: The conspirator would use the checks as collateral for new currency loans, the proceeds of which would then be locked away. As a result, money became scarce, interest rates rose, and stocks fell.

In October 1868, the Erie coterie possessed some $14 million after selling a bogus batch of the railroad’s shares. The group proceeded as outlined with the goal of driving down the stock’s price—which they had sold short with the intention of buying it back at a lower price. The effect of such a sudden withdrawal of funds was dramatic. Minnigerode said loans were called, money “became almost unobtainable, and whoever had borrowed money on stocks was compelled to sell to pay off his loans and trade throughout the country was brought to a perfect standstill. … It required the strong arm of the Treasury to prevent the panic from spreading all over the country.”

55Drew, Fisk, and Gould reaped huge profits and immediately went about making more, according to the historian:

“With the money so obtained they had run up the price of gold and made another large profit; they had then again advanced the price of Erie … and made a larger profit than ever. In the course of these operations they had ruined hundreds … had arrested the whole business of the country … had brought the banks to the verge of suspension and seriously threatened the national credit.

56But all did not end well. Drew became worried about a public backlash. After coming to the assistance of his old friend Henry Keep, who was loaded down with a long position and needed $2 million, Drew distanced himself from the scheme while privately continuing to sell Erie short. Fisk, who had a gift for colorful epithets, called the old man “Turn Tail” and “Danny Cold Feet.”

Drew, who was not warned when Fisk and Gould turned bullish, was caught in the fangs of a short squeeze. Not only did Fisk and Gould start buying Erie, but they unleashed their hoard of greenbacks. Stocks boiled higher. When Drew went to see his compatriots to ask for more time to deliver his shares, he was laughed at and told that “he was the last man who ought to whine over any position in which he has placed himself in regard to Erie.”

57Drew, it seemed, was beyond rescue. However, as Erie’s price soared, a special British issue of stock certificates appeared in New York. With just five minutes to spare, Drew was able to meet his commitments for a loss of roughly $500,000. As a consequence, Gould and Fisk suffered losses of several millions in the broken corner attempt.

to have made—and lost—more money than any other man in Wall Street with the exception of Jacob Little. I remember Jacob Little’s name because I thought it was a funny name for a man to have. The other man, the Shylock, was a notorious locker-up of money. His name has also gone from me. But I remember he was tall and thin and pale. In those days the cliques used to lock up money by borrowing it or, rather, by reducing the amount available to Stock Exchange borrowers. They would borrow it and get a certified check. They wouldn’t actually take the money out and use it. Of course that was rigging. It was a form of manipulation, I think.”

I agree with the old chap. It was a phase of manipulation that we don’t have nowadays.

ENDNOTES

1 Paul Mahoney, “The Origins of the Blue Sky Laws,”

Journal of Law and Economics (April 2003), 229-253.

2 Richard I. Alvarez and Mark J. Astarita, “Introduction to the Blue Sky Laws,”

SECLaw.com, 1.

3 Matthew Hale Smith,

Sunshine and Shadow (1869), 462.

4 William Worthington Fowler,

Ten Years in Wall Street (1870), 92.

5 Henry Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street (New York: Irving Publishing Company, 1908), 728.

6 Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace,

Gotham (2000), 568-569.

7 Richard Wheatley, “The New York Stock Exchange,”

Harper’s Monthly (November 1885): 848.

8 Fowler,

Ten Years in Wall Street, 93.

9 Walter Werner and Steven T. Smith,

Wall Street (1991), 56.

10 “Obituary. Mr. Jacob Little,”

New York Times, March 29, 1865, 4.

11 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 730.

12 Fowler,

Ten Years in Wall Street, 117.

13 “Thomas F. Woodlock,”

New York Times, August 27, 1945, 18.

15 Thomas F. Woodlock,

The Anatomy of a Railroad Report (1895), 3.

16 “Woodlock,”

New York Times. 17 “National Affairs: Take My Money!”

Time, January 31, 1949.

18 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 35.

19 “Ferdinand Ward Married Again,”

New York Times, March 22, 1894, 1.

20 “The Quicksands of Wall Street,”

New York Times, June 25, 1905, magazine section.

21 David Hochfelder, “Where the Common People Could Speculate: The Ticker, Bucket Shops, and the Origins of Popular Participation in Financial Markets, 1880-1920,”

Journal of American History (September 2006), 353.

22 Robert Sobel

, The Big Board (1965), 263.

23 Peter Wyckoff,

Wall Street and the Stock Markets (1972), 59.

24 John Brooks,

Once in Golconda: A True Drama of Wall Street 1920-1938 (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1969), 26.

25 Vanderbilt, Ibid. 134.

26 Richard Barry, “The Vanderbilts,”

Pearson’s Magazine (1911): 715.

28 Fowler,

Ten Years in Wall Street, 333.

29 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 93.

30 Edmund Clarence Stedman, ed.,

The New York Stock Exchange (1905), 297- 298.

31 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 117

34 “Leonard W. Jerome Dead.”

New York Times,March 5, 1891, 8.

35 Sobel,

Panic on Wall Street, 120.

36 Fowler,

Ten Years in Wall Street, 159.

37 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 666.

38 Matthew Hale Smith,

Bulls and Bears of New York (1875), 486.

39 Sobel,

Panic on Wall Street, 120.

40 Fowler,

Ten Years in Wall Street, 259.

42 Smith,

Bulls and Bears of New York, 547.

43 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 110.

44 Kurt C. Schlichting,

Grand Central Terminal (2001), 14.

45 Meade Minnigerode,

Certain Rich Men (1927), 124.

46 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 114.

47 Minnigerode,

Certain Rich Men. 50 Bouck White,

The Book of Daniel Drew (1910), 3-4.

51 Jay Gould,

History of Delaware County (1856), 1.

52 Minnigerode,

Certain Rich Men, 187.

53 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 453.

54 Fowler,

Ten Years in Wall Street, 504.

55 Minnigerode,

Certain Rich Men, 180.

and the story—even the accurately detailed story—of what Daniel Drew or Jacob Little

and the story—even the accurately detailed story—of what Daniel Drew or Jacob Little or Jay Gould could do fifty or seventy-five years ago is scarcely worth listening to. The manipulator to-day has no more need to consider what they did and how they did it than a cadet at West Point need study archery as practiced by the ancients in order to increase his working knowledge of ballistics.

or Jay Gould could do fifty or seventy-five years ago is scarcely worth listening to. The manipulator to-day has no more need to consider what they did and how they did it than a cadet at West Point need study archery as practiced by the ancients in order to increase his working knowledge of ballistics.

when he declared: “The principles of successful stock speculation are based on the supposition that people will continue in the future to make the mistakes that they have made in the past.”

when he declared: “The principles of successful stock speculation are based on the supposition that people will continue in the future to make the mistakes that they have made in the past.” or the bust-up of some bucketing broker and about the millions of sucker money gone to join the silent majority of vanished savings.

or the bust-up of some bucketing broker and about the millions of sucker money gone to join the silent majority of vanished savings. and matched orders, for all that such practices were forbidden by the Stock Exchange. At times the washing was too crude to deceive anyone. The brokers had no hesitation in saying that “the laundry was active” whenever anybody tried to wash up some stock or other, and, as I have said before, more than once they had what were frankly referred to as “bucket-shop drives,” when a stock was offered down two or three points in a jiffy just to establish the decline on the tape and wipe up the myriad shoe-string traders who were long of the stock in the bucket shops. As for matched orders, they were always used with some misgivings by reason of the difficulty of coördinating and synchronising operations by brokers, all such business being against Stock Exchange rules. A few years ago a famous operator canceled the selling but not the buying part of his matched orders, and the result was that an innocent broker ran up the price twenty-five points or so in a few minutes, only to see it break with equal celerity as soon as his buying ceased. The original intention was to create an appearance of activity. Bad business, playing with such unreliable weapons. You see, you can’t take your best brokers into your confidence—not if you want them to remain members of the New York Stock Exchange. Then also, the taxes have made all practices involving fictitious transactions much more expensive than they used to be in the old times.

and matched orders, for all that such practices were forbidden by the Stock Exchange. At times the washing was too crude to deceive anyone. The brokers had no hesitation in saying that “the laundry was active” whenever anybody tried to wash up some stock or other, and, as I have said before, more than once they had what were frankly referred to as “bucket-shop drives,” when a stock was offered down two or three points in a jiffy just to establish the decline on the tape and wipe up the myriad shoe-string traders who were long of the stock in the bucket shops. As for matched orders, they were always used with some misgivings by reason of the difficulty of coördinating and synchronising operations by brokers, all such business being against Stock Exchange rules. A few years ago a famous operator canceled the selling but not the buying part of his matched orders, and the result was that an innocent broker ran up the price twenty-five points or so in a few minutes, only to see it break with equal celerity as soon as his buying ceased. The original intention was to create an appearance of activity. Bad business, playing with such unreliable weapons. You see, you can’t take your best brokers into your confidence—not if you want them to remain members of the New York Stock Exchange. Then also, the taxes have made all practices involving fictitious transactions much more expensive than they used to be in the old times. was expensive to everybody concerned, both in money and in prestige. And it was not a deliberately engineered corner, at that.

was expensive to everybody concerned, both in money and in prestige. And it was not a deliberately engineered corner, at that.

Harlem corners paid big, but the old chap deserved the millions he made out of a lot of short sports, crooked legislators and aldermen who tried to double-cross him.

Harlem corners paid big, but the old chap deserved the millions he made out of a lot of short sports, crooked legislators and aldermen who tried to double-cross him. On the other hand, Jay Gould lost in his Northwestern corner.

On the other hand, Jay Gould lost in his Northwestern corner. Deacon S. V. White made a million in his Lackawanna corner, but Jim Keene dropped a million

Deacon S. V. White made a million in his Lackawanna corner, but Jim Keene dropped a million in the Hannibal & St. Joe deal. The financial success of a corner of course depends upon the marketing of the accumulated holdings at higher than cost, and the short interest has to be of some magnitude for that to happen easily.

in the Hannibal & St. Joe deal. The financial success of a corner of course depends upon the marketing of the accumulated holdings at higher than cost, and the short interest has to be of some magnitude for that to happen easily.

was the acknowledged king of the Public Board in the spring of 1863. His market tips, they tell me, were considered as good as cash in bank. From all accounts he was a great trader and made millions. He was liberal to the point of extravagance and had a great following in the Street—until Henry Keep,

was the acknowledged king of the Public Board in the spring of 1863. His market tips, they tell me, were considered as good as cash in bank. From all accounts he was a great trader and made millions. He was liberal to the point of extravagance and had a great following in the Street—until Henry Keep, known as William the Silent, squeezed him out of all his millions in the Old Southern corner. Keep, by the way, was the brother-in-law of Gov. Roswell P. Flower.

known as William the Silent, squeezed him out of all his millions in the Old Southern corner. Keep, by the way, was the brother-in-law of Gov. Roswell P. Flower. of the Commodore, I gather from the stories I have read that the professional traders sold the stock because it was too high. And the reason they thought it was too high was that it never before had sold so high; and that made it too high to buy; and if it was too high to buy it was just right to sell. That sounds pretty modern, doesn’t it? They were thinking of the price, and the Commodore was thinking of the value! And so, for years afterwards, old-timers tell me that people used to say, “He went short of Harlem!” whenever they wished to describe abject poverty.

of the Commodore, I gather from the stories I have read that the professional traders sold the stock because it was too high. And the reason they thought it was too high was that it never before had sold so high; and that made it too high to buy; and if it was too high to buy it was just right to sell. That sounds pretty modern, doesn’t it? They were thinking of the price, and the Commodore was thinking of the value! And so, for years afterwards, old-timers tell me that people used to say, “He went short of Harlem!” whenever they wished to describe abject poverty. old brokers. He assured me earnestly that Mr. Gould not only was a most unusual man—it was of him that old Daniel Drew shiveringly remarked, “His touch is Death!”—but that he was head and shoulders above all other manipulators past and present. He must have been a financial wizard indeed to have done what he did; there can be no question of that. Even at this distance I can see that he had an amazing knack for adapting himself to new conditions, and that is valuable in a trader. He varied his methods of attack and defense without a pang because he was more concerned with the manipulation of properties than with stock speculation. He manipulated for investment rather than for a market turn. He early saw that the big money was in owning the railroads instead of rigging their securities on the floor of the Stock Exchange. He utilised the stock market of course. But I suspect it was because that was the quickest and easiest way to quick and easy money and he needed many millions, just as old Collis P. Huntington

old brokers. He assured me earnestly that Mr. Gould not only was a most unusual man—it was of him that old Daniel Drew shiveringly remarked, “His touch is Death!”—but that he was head and shoulders above all other manipulators past and present. He must have been a financial wizard indeed to have done what he did; there can be no question of that. Even at this distance I can see that he had an amazing knack for adapting himself to new conditions, and that is valuable in a trader. He varied his methods of attack and defense without a pang because he was more concerned with the manipulation of properties than with stock speculation. He manipulated for investment rather than for a market turn. He early saw that the big money was in owning the railroads instead of rigging their securities on the floor of the Stock Exchange. He utilised the stock market of course. But I suspect it was because that was the quickest and easiest way to quick and easy money and he needed many millions, just as old Collis P. Huntington was always hard up because he always needed twenty or thirty millions more than the bankers were willing to lend him. Vision without money means heartaches; with money, it means achievement; and that means power; and that means money; and that means achievement; and so on, over and over and over.

was always hard up because he always needed twenty or thirty millions more than the bankers were willing to lend him. Vision without money means heartaches; with money, it means achievement; and that means power; and that means money; and that means achievement; and so on, over and over and over.

I could see heads sticking out of windows. They didn’t have sky-scrapers in those days, but I was sure the second-and third-story rubbernecks would tumble out. My father asked what was the matter, and somebody answered something I didn’t hear. I was too busy keeping a death clutch on my father’s hand so that the jostling wouldn’t separate us. The crowd was growing, as street crowds do, and I wasn’t comfortable. Wild-eyed men came running down from Nassau Street and up from Broad as well as east and west on Wall Street. After we finally got out of the jam my father explained to me that the man who was shouting ‘Shylock!’ was So-and-So. I have forgotten the name, but he was the biggest operator in clique stocks in the city and was understood

I could see heads sticking out of windows. They didn’t have sky-scrapers in those days, but I was sure the second-and third-story rubbernecks would tumble out. My father asked what was the matter, and somebody answered something I didn’t hear. I was too busy keeping a death clutch on my father’s hand so that the jostling wouldn’t separate us. The crowd was growing, as street crowds do, and I wasn’t comfortable. Wild-eyed men came running down from Nassau Street and up from Broad as well as east and west on Wall Street. After we finally got out of the jam my father explained to me that the man who was shouting ‘Shylock!’ was So-and-So. I have forgotten the name, but he was the biggest operator in clique stocks in the city and was understood