XXIII

Speculation in stocks will never disappear. It isn’t desirable that it should. It cannot be checked by warnings as to its dangers. You cannot prevent people from guessing wrong no matter how able or how experienced they may be. Carefully laid plans will miscarry because the unexpected and even the unexpectable will happen. Disaster may come from a convulsion of nature or from the weather, from your own greed or from some man’s vanity; from fear or from uncontrolled hope. But apart from what one might call his natural foes, a speculator in stocks has to contend with certain practices or abuses that are indefensible morally as well as commercially.

As I look back and consider what were the common practices twenty-five years ago when I first came to Wall Street, I have to admit that there have been many changes for the better. The old-fashioned bucket shops are gone, though bucketeering “brokerage” houses still prosper at the expense of men and women who persist in playing the game of getting rich quick. The Stock Exchange is doing excellent work not only in getting after these out-and-out swindlers but in insisting upon strict adherence to its rules by its own members. Many wholesome regulations and restrictions are now strictly enforced but there is still room for improvement. The ingrained conservatism of Wall Street rather than ethical callousness is to blame for the persistence of certain abuses.

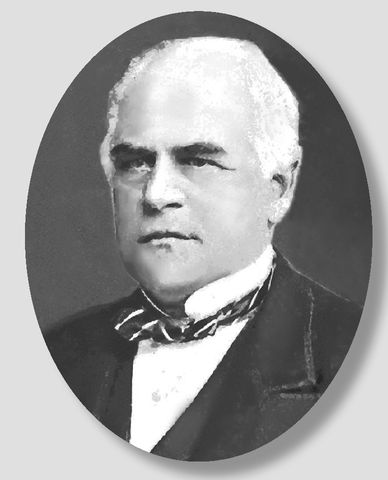

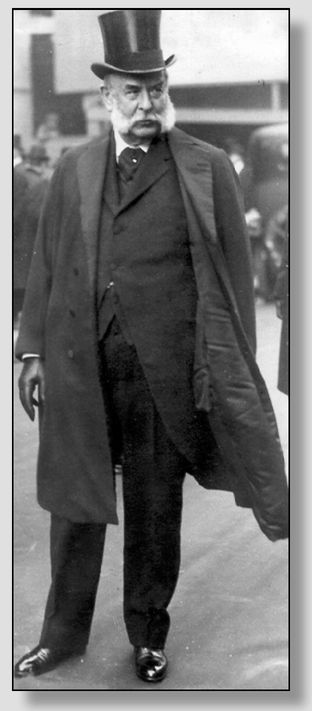

John Pierpont Morgan

Junius Spencer Morgan

23.1So much can be said of John Pierpont Morgan, who is mentioned repeatedly in Reminiscences as a model of speculation, empire building and public service. He was Warren Buffett, George Soros, and Jamie Dimon rolled up into one larger-than-life figure. He was a banker, a railroad builder, and a manager of great enterprises. From his early days battling with Jay Gould to his skirmishes with E. H. Harriman, and of course to his crowning achievement of saving the American financial system from calamity in the Panic of 1907, J. P. Morgan dominated the Gilded Age period between the Civil War and World War I. The Times of London captured his role beautifully:

The life of Mr. Morgan furnished perhaps the most conspicuous example the modern world has seen of the power which the mere possession of wealth may place in the hands of an individual without assistance from offi cial position, title, or the inherited prestige of an historic name. It may also fairly be said to have furnished a not unadmirable example of the intelligent use of that wealth and power.

Mr. Morgan had to bear his full share of abuse, often virulent and scurrilous, but it was the impersonal abuse of those who saw in him only the monstrous outgrowth of what they considered an iniquitous social system, and it is no small tribute to his character that with so great a willingness to discover a cause of grievance against him so little was found to be said in criticism of his integrity or of any individual act of his career. No one, indeed, who had an intimate knowledge of him would hesitate to say that the greatest factor of his success was the confidence which the financial world learned to have in his trustworthiness and singleness of purpose. The game which he played, for such large stakes, he played strictly according to the rules, and if the result was non-moral or injurious to the community, the fault lay not in the play but in the game.

1Morgan had distinguished lineage for his future role as an entrepreneur. His father’s family descended from Captain Miles Morgan, who sailed from Bristol, England, in 1636 and was one of the founders of Springfi eld, Massachusetts. His grandfather, Joseph Morgan, began life as a farmer but leveraged a small inheritance into two taverns, a stagecoach line, a hotel in Hartford, Connecticut, a founding stake in the Aetna Fire Insurance Co., and investments in banks, canals, railroads and steamships. Joseph left his one son, Junius Spencer Morgan, a $3 million inheritance. Junius used it to start a bank, then left to become a partner in a large dry-goods business. He later headed to London to become a partner in a bank that would be renamed J. S. Morgan & Co. When he died, Junius in turn left his one son, John Pierpont Morgan, a $10 million inheritance.

Difficult as profitable stock speculation always has been it is becoming even more difficult every day. It was not so long ago when a real trader could have a good working knowledge of practically every stock on the list. In 1901, when

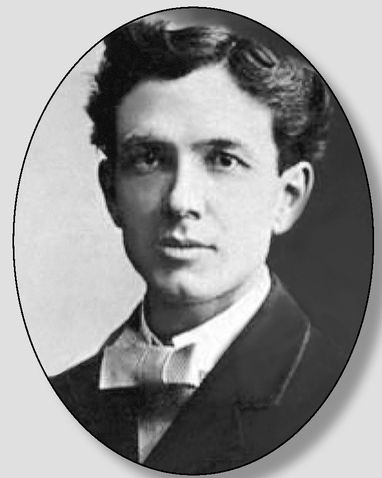

John Pierpont Morgan Jr.

J. P. was born in 1837 in Hartford. He attended a Boston high school before moving to Germany to study mathematics, history, and political economy at the University of Göttingen. In 1860, upon returning to the United States, he was made the American agent for his father’s business. In 1871, Morgan joined with Anthony Drexel and formed the fi rm Drexel, Morgan & Co. Upon his father’s death in 1890, Morgan inherited the London business and its global connections. And with Drexel’s death in 1893, Morgan became the patriarch of a vast fi nancial empire. In 1895, the fi rm was renamed J. P. Morgan & Co.

The firm was the first global American bank. In 1899, it extended a loan to the Mexican government to restructure its national debt. Later it helped the British fund the Boer War in South Africa, and helped Thomas Edison form General Electric. By 1901, J. P. Morgan & Co. was worth some $1.1 billion, or $28 billion in today’s dollars.

2Morgan diversified. He won control of various railroads, including the New York Central and the New York, New Haven & Hartford. He was a director of Western Union, Aetna Insurance, and General Electric companies. Morgan would typically gain control of entities by reorganizing them once they fell into bankruptcy—a process that became known as re-Morganizing. Banker Henry Clews, who said Morgan had “the driving power of a locomotive,” described the process: “They have been financial physicians, healing sick corporate bodies; monetary surgeons, amputating needless expenditures and reckless methods; or, in perhaps more happy figure, skilful pruners of the vine, that the ultimate vintage might be more abundant.”

3Morgan also assumed the mantle of responsibility of ensuring the stability of the financial system that was later given to the Federal Reserve after its creation in 1913. Of course, there was also a profit to be had for Morgan’s interests, for altruism was not one of his main personality traits. He took advantage of the Panic of 1907 to secure control of Tennessee Iron & Coal, a competitor to his U.S. Steel conglomerate, for instance, and also turned a buck in helping the U.S. Treasury rebuild its gold reserves in 1895-1896.

Good examples of his breathless confi dence occurred during his formative years. In 1859 while in New Orleans, on a whim he bought an entire boatload of Brazilian coffee that had arrived in port without a buyer. He later resold it for a profi t. Later, he helped fi nance a man’s endeavor to buy old, surplus smoothbore rifl es from the U.S. Army, have the barrels fixed for better range and accuracy, and sell them back to the government at six times the price.

4 And he was not above using extraordinary means to achieve his purposes. In his fight against the Gould forces over control of the Albany & Susquehanna railroad, Morgan allegedly “hurled chubby Jim Fisk down a fl ight of stairs,” according to a biographer. In his private life, Morgan enjoyed collecting rare books and works of art for his library. He died in 1913 while traveling in Rome. The New York Stock Exchange remained closed the morning of his funeral out of respect. When trading resumed, volume was very light.

6 Carrying on the family tradition, J. P. left his fortune and business to his only son, John Pierpont Morgan Jr.

5Morgan’s name lives on. After the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 forced banks to separate investment banking activities from commercial banking, some of the partners of J. P. Morgan & Co. left to form Morgan Stanley. The two banks maintained a close relationship with each other and with their London cousin, Morgan, Grenfell & Co. Regulatory changes and mergers pulled the old House of Morgan apart. Morgan, Grenfell was acquired by Deutsche Bank in 1990, and later J. P. Morgan & Co. merged with Chase Manhattan Bank to form one of the top three banks in the United States.

J. P. Morgan

brought out the United States Steel Corporation, which was merely a consolidation of lesser consolidations most of which were less than two years old, the Stock Exchange had 275 stocks on its list and about 100 in its “unlisted

23.2Traditionally, securities that were unable to meet the listing requirements of the New York Stock Exchange were traded in alternative exchanges or “on the curb.” In March 1885, the NYSE formed a special department to handle unlisted securities. This came just weeks after the Consolidated Exchange opened and presented a new competitive threat. One of the main distinctions was that the unlisted securities were not granted an official quotation from the exchange.

7

Shares of industrial companies dominated the unlisted department in its early years (steelmakers and railroads dominated the main exchange). In 1895, some 435 industrial companies traded in the unlisted category, though just three of those—American Sugar Refining, National Lead, and U.S. Leather—comprised 94% of the group’s $13.6 million trade volume.

8The unlisted department was not around for long. In 1910, the NYSE abolished it and adopted new rules requiring that stocks traded on the exchange meet strict listing requirements, including publication of financial reports.

923.2 Guaranteed stocks were a class of equity similar to bonds that had higher standing than preferred shares. They had a set dividend that was guaranteed by a lease issued to a second company and would be paid regardless of the earnings of the issuing company. In the event of default, guaranteed stockholders were secondary to bond-holders but ahead of the common stockholders.

10 Guaranteed stocks were not subject to state and local taxes.

Railroad companies were the primary issuers of guaranteed stocks, as larger lines would lease track rights from smaller lines. For example, the Albany & Susquehanna railroad would issue guaranteed stock backed by a lease paid by the larger Delaware & Hudson line.

There were considerable risks in the securities due to illiquidity, as Livermore mentions. According to a contemporary account: “There are…some serious disadvantages to even the best of such stocks, the foremost being the limited market and extreme inactivity of the stock, which makes it more or less difficult to dispose of immediately should such a contingency arise.”

11

epartment”;23.2 and this included a lot that a chap didn’t have to know anything about because they were small issues, or inactive by reason of being minority or guaranteed stocks

and therefore lacking in speculative attractions. In fact, an overwhelming majority were stocks in which there had not been a sale in years. Today there are about 900 stocks on the regular list and in our recent active markets about 600 separate issues were traded in.

23.4 Moreover, the old groups or classes of stocks were easier to keep track of. They not only were fewer but the capitalization was smaller and the news a trader had to be on the lookout for did not cover so wide a field. But today, a man is trading in everything; almost every industry in the world is represented. It requires more time and more work to keep posted and to that extent stock speculation has become much more difficult for those who operate intelligently.

There are many thousands of people who buy and sell stocks speculatively but the number of those who speculate profitably is small. As the public always is “in” the market to some extent, it follows that there are losses by the public all the time. The speculator’s deadly enemies are: Ignorance, greed, fear and hope. All the statute books in the world and all the rules of all the Exchanges on earth cannot eliminate these from the human animal. Accidents which knock carefully conceived plans skyhigh also are beyond regulation by bodies of cold-blooded economists or warm-hearted philanthropists. There remains another source of loss and that is, deliberate misinformation as distinguished from straight tips. And because it is apt to come to a stock trader variously disguised and camouflaged, it is the more insidious and dangerous.

The average outsider, of course, trades either on tips or on rumours, spoken or printed, direct or implied. Against ordinary tips you cannot guard. For instance, a lifelong friend sincerely desires to make you rich by telling you what he has done, that is, to buy or sell some stock. His intent is good. If the tip goes wrong what can you do? Also against the professional or crooked tipster the public is protected to about the same extent that he is against gold-bricks or wood-alcohol.

But against the typical Wall Street rumours, the speculating public has neither protection nor redress. Wholesale dealers in securities, manipulators, pools and individuals resort to various devices to aid them in disposing of their surplus holdings at the best possible prices. The circulation of bullish items by the newspapers and the tickers is the most pernicious of all.

Get the slips of the financial news-agencies any day and it will surprise you to see how many statements of an implied semi-official nature they print. The authority is some “leading insider” or “a prominent director” or “a high official” or someone “in authority” who presumably knows what he is talking about. Here are today’s slips. I pick an item at random. Listen to this: “A leading banker says it is too early yet to expect a declining market.”

Did a leading banker really say that and if he said it why did he say it? Why does he not allow his name to be printed? Is he afraid that people will believe him if he does?

Here is another one about a company the stock of which has been active this week. This

23.4 Livermore’s lament about the complexity of tracking the industry trends and business developments between 1901 and the 1920s surely pales in comparison to how he would feel about today’s marketplace: In mid-2009, the

NYSE Euronext listed over 4,000 tradable issues. The NYSE Amex, the successor to the Curb Market of Livermore’s time, listed another 676 equity securities, and the NASDAQ listed 2,820 issues.

23.5 The terms “gold-bricks” and “wood-alcohol” are more slang for a fraud or swindle. “Gold-brick” was a term used to describe con men who would sell bricks of “gold” that were in reality lead or some other weighty material coated with gold. John Hill wrote Gold Bricks of Speculation, a resource for the average investor, in the hope it would “make the difference between legitimate and illegitimate methods so clear that the reader will not be duped into buying any of the ‘Gold Bricks of Speculation.’”

12Wood-alcohol, or methyl alcohol, was a cheap but poisonous substitute for ethyl or drinking alcohol used during Prohibition. Bootleggers would try to cook the methyl alcohol out of industrial alcohol through boiling, but their customers risked blindness or even death.

13 While methyl alcohol is a distillate of wood, ethyl alcohol comes from the fermentation of fruits or grains.

23.6 Livermore rails against the media’s practice of allowing insiders to provide self-serving comments without furnishing their names. He would have been aghast at the current situation in which anyone with a computer connection can hold themselves out to be an expert in stocks on a blog, and create the mysterious aura required to influence public opinion.

He would also have been appalled at the ease by which canny short sellers could manipulate public opinion in minutes by spreading false rumors virally through social-media web sites. A famous New Yorker cartoon of the early online era showed a mutt typing into a computer while remarking to another mutt at his side, “On the Internet, no one knows you’re a dog.”

14 The anonymity that Livermore found so harmful in the 1920s has thus been magnified today, for on Twitter and in chat rooms, no one knows whether a bearish commenter on a stock is a short seller, a disgruntled employee with an ax to grind, or a rival company exec.

In August, 2000, the Securities and Exchange Commission tried to rein in some of the most abusive practices of insiders through a new rule, Regulation FD. It banned the selective disclosure of information by issuers to an inner circle of stock analysts or major shareholders, and instead demanded that any material new data be made available to both pros and the public at the same time. The unfortunate result was a dramatic decrease in the dissemination of any information.

time the man who makes the statement is a “prominent director.” Now which—if any—of the company’s dozen directors is doing the talking? It is plain that by remaining anonymous nobody can be blamed for any damage that may be done by the statement.

Quite apart from the intelligent study of speculation everywhere the trader in stocks must consider certain facts in connection with the game in Wall Street. In addition to trying to determine how to make money one must also try to keep from losing money. It is almost as important to know what not to do as to know what should be done. It is therefore well to remember that manipulation of some sort enters into practically all advances in individual stocks and that such advances are engineered by insiders with one object in view and one only and that is to sell at the best profit possible. However, the average broker’s customer believes himself to be a business man from Missouri if he insists upon being told why a certain stock goes up. Naturally, the manipulators “explain” the advance in a way calculated to facilitate distribution. I am firmly convinced that the public’s losses would be greatly reduced if no anonymous statements of a bullish nature were allowed to be printed. I mean statements calculated to make the public buy or hold stocks.

The overwhelming majority of the bullish articles printed on the authority of unnamed directors or insiders convey unreliable and misleading impressions to the public. The public loses many millions of dollars every year by accepting such statements as semi-official and therefore trustworthy.

Say for example that a company has gone through a period of depression in its particular line of business. The stock is inactive. The quotation represents the general and presumably accurate belief of its actual value. If the stock were too cheap at that level somebody would know it and buy it and it would advance. If too dear somebody would know enough to sell it and the price would decline. As nothing happens one way or another nobody talks about it or does anything.

The turn comes in the line of business the company is engaged in. Who are the first to know it, the insiders or the public? You can bet it isn’t the public. What happens next? Why, if the improvement continues the earnings will increase and the company will be in position to resume dividends on the stock; or, if dividends were not discontinued, to pay a higher rate. That is, the value of the stock will increase.

Say that the improvement keeps up. Does the management make public that glad fact? Does the president tell the stockholders? Does a philanthropic director come out with a signed statement for the benefit of that part of the public that reads the financial page in the newspapers and the slips of the news agencies? Does some modest insider pursuing his usual policy of anonymity come out with an unsigned statement to the effect that the company’s future is most promising? Not this time. Not a word is said by anyone and no statement whatever is printed by newspapers or tickers.

The value-making information is carefully kept from the public while the now taciturn “prominent insiders” go into the market and buy all the cheap stock they can lay their hands on. As this well-informed but unostentatious buying keeps on, the stock rises. The financial reporters, knowing that the insiders ought to know the reason for the rise, ask questions. The unanimously anonymous insiders unanimously declare that they have no news to give out. They do not know that there is any warrant for the rise. Sometimes they even state that they are not particularly concerned with the vagaries of the stock market or the actions of stock speculators.

The rise continues and there comes a happy day when those who know have all the stock they want or can carry. The Street at once begins to hear all kinds of bullish rumours. The tickers tell the traders “on good authority” that the company has definitely turned the corner. The same modest director who did not wish his name used when he said he knew no warrant for the rise in the stock is now quoted—of course not by name—as saying that the stockholders have every reason to feel greatly encouraged over the outlook.

Urged by the deluge of bullish news items the public begins to buy the stock. These purchases help to put the price still higher. In due course the predictions of the uniformly unnamed directors come true and the company resumes dividend payments; or increases the rate, as the case may be. With that the bullish items multiply. They not only are more numerous than ever but much more enthusiastic. A “leading director,” asked point blank for a statement of conditions, informs the world that the improvement is more than keeping up. A “prominent insider,” after much coaxing, is finally induced by a news-agency to confess that the earnings are nothing short of phenomenal. A “well-known banker,” who is affiliated in a business way with the company, is made to say that the expansion in the volume of sales is simply unprecedented in the history of the trade. If not another order came in the company would run night and day for heaven knows how many months. A “member of the finance committee,” in a double-leaded manifesto, expresses his astonishment at the public’s astonishment over the stock’s rise. The only astonishing thing is the stock’s moderation in the climbing line. Anybody who will analyse the forthcoming annual report can easily figure how much more than the market-price the book-value of the stock is. But in no instance is the name of the communicative philanthropist given.

23.7While Lefevre paints a portrait here of omnipotent directors who used their industry knowledge to cheat the public, the truth is that even in the 1920s being an insider no instant path to riches. There were plenty of corporate titans who blew their fortunes in the market.

One of the most sensational rises and failures was experienced by William Crapo Durant, the eccentric founder of General Motors. The grandson of a Michigan governor who was born in Boston in 1861, Durant started his career as a cigar salesman but showed an early entrepreneurial streak by parlaying a $2,000 investment in a horse-drawn carriage business in Flint, Michigan, into a $2 million business with worldwide sales in the mid-1890s.

He was among the few in the buggy-whip set to transition to autos, and created General Motors in 1908 by consolidating 13 small car makers and 10 parts makers, including Cadillac, Buick, and Oldsmobile. Big investors in the new firm ousted him in 1911 over complaints about his risk taking, but he then started a new economy-car firm with famed racer Louis Chevrolet, and later managed to win back GM through a clever series of stock transactions: Leading the bull pool himself, he acquired shares in the company cheaply during a weak spot in the economy, and then manipulated the stock from $82 in January 1916 to $558 in December that year. “The visionary gambler was on the loose,” said historian Kenneth Fisher.

15

During his second term at the helm of GM, he brought in the managers who would ultimately create the midcentury glory of the firm—organizational genius Alfred Sloan an Charles Kettering—but World War I was harsh on the company’s sales, and ultimately Durant was wiped out of stock he had bought on 10% margin. Shares rose in the 1919 expansion, but then plunged again in the 1920 recession, wiping Durant out a third time. Chemicals tycoon Pierre DuPont, who was a major GM shareholder, brought in J. P. Morgan & Co. to reorganize GM and issue new stock, and although Durant worked tirelessly in bull syndicates to bolster the price, he ended up $90 million in debt and was booted again from his fi rm.

16In the mid-1920s bull market, the ultimate car salesman was back on his feet again and became a major player on the Street right alongside Livermore, launching a new firm, Durant Motors, and running bull pools in a variety of stocks in conjunction with other dilettantes from the fast-growing auto industry, including the Fisher brothers, who had made a fortune in carriage and auto frames.

But being an insider didn’t help Durant avoid the devastating first leg of the 1929 crash, or the hubris of borrowing to buy more stocks in 1930 just ahead of the second leg of the crash. By 1932, he had lost his fortune once and for all. He declared bankruptcy in 1936, and ended his years living on a small GM pension and managing a bowling alley in Flint. He died in 1947 at age 86.

As long as the earnings continue good and the insiders do not discern any sign of a let up in the company’s prosperity they sit on the stock they bought at the low prices. There is nothing to put the price down, so why should they sell? But the moment there is a turn for the worse in the company’s business, what happens? Do they come out with statements or warnings or the faintest of hints? Not much. The trend is now downward. Just as they bought without any flourish of trumpets when the company’s business turned for the better, they now silently sell. On this inside selling the stock naturally declines. Then the public begins to get the familiar “explanations.” A “leading insider” asserts that everything is O.K. and the decline is merely the result of selling by bears who are trying to affect the general market. If on one fine day, after the stock has been declining for some time, there should be a sharp break, the demand for “reasons” or “explanations” becomes clamorous. Unless somebody says something the public will fear the worst. So the news-tickers now print something like this: “When we asked a prominent director of the company to explain the weakness in the stock, he replied that the only conclusion he could arrive at was that the decline today was caused by a bear drive. Underlying conditions are unchanged. The business of the company was never better than at present and the probabilities are that unless something entirely unforeseen happens in the meanwhile, there will be an increase in the rate at the next dividend meeting. The bear party in the market has become aggressive and the weakness in the stock was clearly a raid intended to dislodge weakly held stock.” The news-tickers, wishing to give good measure, as likely as not will go on to state that they are “reliably informed” that most of the stock bought on the day’s decline was taken by inside interests and that the bears will find that they have sold themselves into a trap. There will be a day of reckoning.

In addition to the losses sustained by the public through believing bullish statements and buying stocks, there are the losses that come through being dissuaded from selling out. The next best thing to having people buy the stock the “prominent insider” wishes to sell is to prevent people from selling the same stock when he does not wish to support or accumulate it. What is the public to believe after reading the statement of the “prominent director”? What can the average outsider think? Of course, that the stock should never have gone down; that it was forced down by bear-selling and that as soon as the bears stop the insiders will engineer a punitive advance during which the shorts will be driven to cover at high prices. The public properly believes this because it is exactly what would happen if the decline had in truth been caused by a bear raid.

The stock in question, notwithstanding all the threats or promises of a tremendous squeeze of the over-extended short interest, does not rally. It keeps on going down. It can’t help it. There has been too much stock fed to the market from the inside to be digested.

And this inside stock that has been sold by the “prominent directors” and “leading insiders” becomes a football among the professional traders. It keeps on going down. There seems to be no bottom for it. The insiders knowing that trade conditions will adversely affect the company’s future earnings do not dare to support that stock until the next turn for the better in the company’s business. Then there will be inside buying and inside silence.

I have done my share of trading and have kept fairly well posted on the stock market for many years and I can say that I do not recall an instance when a bear raid caused a stock to decline extensively. What was called bear raiding was nothing but selling based on accurate knowledge of real conditions. But it would not do to say that the stock declined on inside selling or on inside non-buying. Everybody would hasten to sell and when everybody sells and nobody buys there is the dickens to pay.

The public ought to grasp firmly this one point: That the real reason for a protracted decline is never bear raiding. When a stock keeps on going down you can bet there is something wrong with it, either with the market for it or with the company. If the decline were unjustified the stock would soon sell below its real value and that would bring in buying that would check the decline. As a matter of fact, the only time a bear can make big money selling a stock is when that stock is too high. And you can gamble your last cent on the certainty that insiders will not proclaim that fact to the world.

23.8 In a typical corporate strategy at the time, even in the face of recent antitrust regulation, Charles Mellen set about reducing the competitive threat faced by the New Haven. Mellen was eager to make a name for himself in the Morgan empire after playing a small role at the Northern Pacific, boxed in by members of the James Hill family. Morgan, according to historian Ron Chernow, wanted “to take over every form of transportation in New England and wantonly usurped steamship lines, interurban electric trolleys, rapid transit systems—anything that threatened their monopoly.”

17

Burton Hendrick, writing in McClure’s Magazine, expands on the events:

Mellen first proceeded to put an end to the “intolerable” trolley situation. In seizing nearly all of the trolley lines in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and western Massachusetts, he paid little attention to expense. Wherever he saw a trolley line he proceeded to lay hand upon it. The prices demanded by the speculative adventurers who had “reorganized” to properties did not frighten Mellen for the movement.…In Mellen’s view-point, however, the proceeding justified itself; it took the whole trolley business of two states out of the hands of possible competitors, and anchored it, for all time, in the possession of the New Haven road.

18In the end, New Haven was not able to sustain the massive debt load it assumed during its acquisition frenzy. A scandal followed as it was revealed that Mellen handed out millions of dollars in bribes to keep politicians and regulators out of his way. He even paid a Harvard professor to deliver lectures favoring lenient regulation of railways.

It soon became apparent that something was wrong. New Haven, which had earned a reputation for thriftiness and conservatism in the years before Mellen and Morgan, was forced to cut expenses to stay solvent. Staff cuts and mechanical neglect resulted in 11 deadly train wrecks in 1911 and 1912. As the public grew outraged, and the government’s Interstate Commerce Commission recommended that the New Haven be separated from its steamship and trolley holdings, J. P. Morgan’s son, Jack Morgan, fired Mellen.

19Of course, the classic example is the New Haven. Everybody knows today what only a few knew at the time. The stock sold at 255 in 1902 and was the premier railroad investment of New England. A man in that part of the country measured his respectability and standing in the community by his holdings of it. If somebody had said that the company was on the road to insolvency he would not have been sent to jail for saying it. They would have clapped him in an insane asylum with other lunatics. But when a new and aggressive president was placed in charge by Mr. Morgan and the débâcle began, it was not clear from the first that the new policies would land the road where it did. But as property after property began to be saddled in the Consolidated Road at inflated prices, a few clear sighted observers began to doubt the wisdom of the Mellen policies. A trolley system

was bought for two million and sold to the New Han 23.9 for $10,000,000; whereupon a reckless man or two committed lèse majeste by saying that the management was acting recklessly. Hinting that not even the New Haven could stand such extravagance was like impugning the strength of Gibraltar.

Of course, the first to see breakers ahead were the insiders. They became aware of the real condition of the company and they reduced their holdings of the stock. On their selling as well as on their non-support, the price of New England’s gilt-edged railroad stock began to yield. Questions were asked, and explanations were demanded as usual; and the usual explanations were promptly forthcoming. “Prominent insiders” declared that there was nothing wrong that they knew of and that the decline was due to reckless bear selling. So the “investors” of New England kept their holdings of New York, New Haven & Hartford stock. Why shouldn’t they? Didn’t insiders say there was nothing wrong and cry bear selling? Didn’t dividends continue to be declared and paid?

In the meantime the promised squeeze of the bears did not come but new low records did. The insider selling became more urgent and less disguised. Nevertheless public spirited men in Boston were denounced as stock-jobbers and demagogues for demanding a genuine explanation for the stock’s deplorable decline that meant appalling losses to everybody in New England who had wanted a safe investment and a steady dividend payer.

That historic break from $255 to $12 a share never was and never could have been a bear drive. It was not started and it was not kept up by bear operations. The insiders sold right along and always at higher prices than they could have done if they had told the truth or allowed the truth to be told. It did not matter whether the price was 250 or 200 or 150 or 100 or 50 or 25, it still was too high for that stock, and the insiders knew it and the public did not. The public might profitably consider the disadvantages under which it labours when it tries to make money buying and selling the stock of a company concerning whose affairs only a few men are in position to know the whole truth.

The stocks which have had the worst breaks in the past 20 years did not decline on bear raiding. But the easy acceptance of that form of explanation has been responsible for losses by the public amounting to millions upon millions of dollars. It has kept people from selling who did not like the way his stock was acting and would have liqui

23.9The New York & New Haven Railroad was incorporated in Connecticut in 1844, and the original 63-mile line was completed four years later. Passenger volumes grew rapidly as the road lay along the important overland route between New York and Boston. Tragedy struck in 1853 when an early-morning express steamed through an open drawbridge, killing 42 people and resulting in a $500 million lawsuit. The following year, company president Robert Schuyler, a nephew of the first secretary of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton, fled to Italy after illegally issuing $2 million in stock. A magazine writer at the time noted:

The discovery of the…fraud created a universal panic that for a while threatened to break up the railroad system throughout the country. Stocks precipitately declined, and were unsalable even at a mere nominal price; while those who had borrowed money upon railroad stocks or bonds…were required to make

immediate payment.

20A second road, the Hartford & New Haven, was chartered in 1833 and finished a few years later. The two roads were merged in 1872. By 1885, the New Haven, as the road was commonly called, was 265 miles long and had annual revenues of roughly $4 million. By 1900, the road stretched for 2,000 miles throughout Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island and revenues totaled $40 million.

21J. P. Morgan took control of the New Haven shortly thereafter and selected Charles S. Mellen, the former president of the Northern Pacific, to take the reins. Mellen was later censured by the government for monopolistic practices and neglecting maintenance. He resigned in 1913, the same year J. P. Morgan died. The road struggled despite its favorable location before going bankrupt in 1935. Eventually, the New Haven’s properties were absorbed into the Penn Central amalgamation of 1969 before becoming part of Amtrak in the 1970s. Amtrak’s high-speed Acela Express runs on old New Haven track.

23.10 Charles F. Woerishoffer was one of the most famous bear operators of the mid-1800s. Born in Gelnhausen, Germany, in 1843, he came to the United States as a boy in search of his fortune. He appeared in Wall Street in 1865 first as a clerk and later as a cashier for Rutten & Bonn, a banking and brokerage operation.

22 By 1870, Woerishoffer had his own seat on the NYSE.

Woerishoffer & Co. soon followed, and it was prosperous from the start.

23 A colleague remarked on his daring: “He could have marched upon a cannon’s mouth with a jest on his lips.”

24 And he won notoriety in 1879 by taking on Jay Gould and Russell Sage in a fight over control of a majority of the bonds of the Kansas Pacific Railroad, which was eventually merged into the Union Pacific.

Later, German investors would help Woerishoffer build the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad. Other exploits included the pricking of the Northern Pacific bubble blown by Henry Villard in 1883. Woerishoffer had examined the line and found that the underlying earnings did not justify the road’s fanciful stock price. He went against the established powers of the time, which included Drexel, Morgan & Co., and won millions “for his allegiance to the fact that stocks cannot be bulled with much satisfaction for any length of time with net earnings out of the question” according to the Times.

25He was not beholden to the bear side but, like Livermore, would seek out opportunities as they arose. The trader understood the importance of good sources of information: In one example, he went short after learning the railroads were not saving enough of their net earnings. Pneumonia killed him in 1886 at the age of 43 just as he was preparing for a trip back to Germany.

Henry Clews compared Woerishoffer favorably to Bismarck, Napoleon, and Ulysses S. Grant, saying, “The results of his life work show what can be accomplished by any man who sets himself at work upon an idea, and who devotes himself steadily and persistently to a course of action for the development and perfection of the principle which actuates his life.”

26 His natural bearishness can be traced to a disappointment in the failures of men and a lack of confidence in their corporations. He believed history had shown that most companies were destined to failure as the ravages of capitalism wore down their competitive advantages. Said Clews: “It does not matter how successful the development of the business industries of this country may be hereafter, there will always be found men who will speculate upon their ruination.

27

dated if they had not expected the price to go right back after the bears stopped their raiding. I used to hear Keene blamed in the old days. Before him they used to accuse Charley Woerishoffer 23.10 or Addison Cammack. Later on I became the stock excuse.

I recall the case of Intervale Oil. There was a pool in it that put the stock up and found some buyers on the advance. The manipulators ran the price to 50. There the pool sold and there was a quick break. The usual demand for explanations followed. Why was Intervale so weak? Enough people asked this question to make the answer important news. One of the financial news tickers called up the brokers who knew the most about Intervale Oil’s advance and ought to be equally well posted as to the decline. What did these brokers, members of the bull pool, say when the news agency asked them for a reason that could be printed and sent broadcast over the country? Why, that Larry Livingston was raiding the market! And that wasn’t enough. They added that they were going to “get” him. But of course, the Intervale pool continued to sell. The stock only stood then about $12 a share and they could sell it down to 10 or lower and their average selling price would still be above cost.

It was wise and proper for insiders to sell on the decline. But for outsiders who had paid 35 or 40, it was a different matter. Reading what the tickers printed there outsiders held on and waited for Larry Livingston to get what was coming to him at the hands of the indignant inside pool.

In a bull market and particularly in booms the public at first makes money which it later loses simply by overstaying the bull market. This talk of “bear raids” helps them to overstay. The public should beware of explanations that explain only what unnamed insiders wish the public to believe.

23.11 After spending decades in the business as a bull, a bear, a trader, an investor, a syndicator, and a manipulator, Livermore knew every trick in the book and made up more as he went along. Yet despite many successes, massive losses haunted his career. A decade after Reminiscences was published, he would declare bankruptcy for the fourth time in March, 1934.

28 He had made millions by being short stocks during the great crash of 1929, but suffered a series of setbacks following a very sharp, multimonth rally that began in mid-1932.

The New York Times‘ account of that bankruptcy shed light on all of Livermore’s setbacks, since they were each variations of the same theme. The Times said the plunger’s assets amounted to only $184,900, which included a life insurance policy worth $150,000; seats on the Chicago Board of Trade and Commodity Exchange valued at $10,500; and $20,000 worth of jewelry pledged as collateral for loans. His liabilities included $561,000 for unpaid federal and state income taxes; $9,000 promised to a dancer for keeping him “cheered and mused”

29 while getting his second divorce; $250,000 promised to a Russian woman in his office; $125,000 owed to his second wife; $100,000 to his current wife; and $142,525 to disgraced banker Joseph W. Harriman of the failed Harriman National Bank.

Here’s how Time magazine described his fall from grace that week: When the Coolidge market broke, there were angry stories that Jesse L. Livermore had smashed it. As the public began to get out of Wall Street, his fame receded. For the first time in 25 years he did not seem to prosper in a falling market. He gave up the big office overlooking the park. His second wife divorced him in 1932 and promptly married a onetime Federal Prohibition agent. For his third wife he took a brewer’s daughter. The great Livermore estate at Great Neck, where the shrubbery alone was worth $150,000, netted $168,000 at auction. Last December Jesse Livermore was a 27-hour news headliner when he walked out of his Park Avenue apartment one afternoon, lost his bearings, spent the night at a hotel, and returned home the next day.

Perhaps Jesse L. Livermore will come back as he has done three times before. That was what his lawyers had in mind last week when they declared: ‘Mr. Livermore has made three very large fortunes. ... He has failed three times, on each occasion has paid 100 cents on the dollar with interest, and hopes to do so

again.

30 Yet his luck had run out. Livermore’s name would surface again with reverence whenever the subject of great traders and manipulations arose, but new regulations in 1933 and 1934 essentially brought his era to an end.

ENDNOTES

1 “Mr. Pierpont Morgan,”

New York Times, April 1, 1913, 6.

2 “John Pierpont Morgan,”

National Cyclopaedia of American Biography (1910), 66.

3 Henry Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street (New York: Irving Publishing Company, 1908), 681.

4 Ron Chernow,

The House of Morgan (1990), 21-22.

6 “Financial Markets,”

New York Times, April 15, 1913, 14.

7 Robert Sobel,

The Curbstone Brokers (2000), 57.

8 Lance E. David and Robert J. Cull,

International Capital Markets and American Economic Growth, 1820-1914 (2002), 45.

9 S. N. D. North, ed.,

The American Year Book (1911), 387.

10 David Francis Jordan,

Jordan on Investments (1920), 113.

11 Thomas Conway and Albert William Atwood.

Investment and Speculation (1911), 132.

12 John Hill Jr.,

Gold Bricks of Speculation (1904), 19.

13 “The Trust about Poison Liquor,”

Popular Science (April 1927): 17.

14 The New Yorker. July 5, 1993, 61.

15 Kenneth L. Fisher.

100 Minds That Made the Market (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2007).

17 Chernow,

The House of Morgan, 175.

18 Burton J. Hendrick, “Bottling Up New England,”

McClure’s Magazine (1912): 552.

19 Chernow,

The House of Morgan, 177.

20 “Commercial Chronicle and Review,”

Hunt’s Merchants’ Magazine and Commercial Review (1854): 207.

21 John F. Stover,

Historical Atlas of the American Railroads (1999), pp. 104-105

22 “August Rutten,”

New York Times, August 23, 1895, 2.

23 “C. F. Woerishoffer Dead,”

New York Times, May 11, 1886, 1.

24 Maury Klein,

The Life and Legend of Jay Gould (1986), 320.

26 Clews,

Fifty Years in Wall Street, 425.

28 “Livermore, Plunger, Bankrupt Fourth Time,”

New York Times, March 6, 1934, 1.

29 “Fourth Down,”

Time, March 19, 1934.

brought out the United States Steel Corporation, which was merely a consolidation of lesser consolidations most of which were less than two years old, the Stock Exchange had 275 stocks on its list and about 100 in its “unlisted

brought out the United States Steel Corporation, which was merely a consolidation of lesser consolidations most of which were less than two years old, the Stock Exchange had 275 stocks on its list and about 100 in its “unlisted

and therefore lacking in speculative attractions. In fact, an overwhelming majority were stocks in which there had not been a sale in years. Today there are about 900 stocks on the regular list and in our recent active markets about 600 separate issues were traded in.

and therefore lacking in speculative attractions. In fact, an overwhelming majority were stocks in which there had not been a sale in years. Today there are about 900 stocks on the regular list and in our recent active markets about 600 separate issues were traded in. But against the typical Wall Street rumours, the speculating public has neither protection nor redress. Wholesale dealers in securities, manipulators, pools and individuals resort to various devices to aid them in disposing of their surplus holdings at the best possible prices. The circulation of bullish items by the newspapers and the tickers is the most pernicious of all.

But against the typical Wall Street rumours, the speculating public has neither protection nor redress. Wholesale dealers in securities, manipulators, pools and individuals resort to various devices to aid them in disposing of their surplus holdings at the best possible prices. The circulation of bullish items by the newspapers and the tickers is the most pernicious of all.

was bought for two million and sold to the New Han 23.9 for $10,000,000; whereupon a reckless man or two committed lèse majeste by saying that the management was acting recklessly. Hinting that not even the New Haven could stand such extravagance was like impugning the strength of Gibraltar.

was bought for two million and sold to the New Han 23.9 for $10,000,000; whereupon a reckless man or two committed lèse majeste by saying that the management was acting recklessly. Hinting that not even the New Haven could stand such extravagance was like impugning the strength of Gibraltar.