In the preceding chapter, we studied kinematics, which is the description of motion in terms of an object’s position, velocity, and acceleration. In this chapter, we’ll begin our study of dynamics, which is the explanation of motion in terms of the forces that act on an object.

Simply put, a force is a push or pull exerted by one object on another. If you pull on a rope attached to a crate, you create a tension in the rope that pulls the crate. When a sky diver is falling through the air, the Earth exerts a downward pull called the gravitational force, and the air exerts an upward force called air resistance. When you stand on the floor, the floor provides an upward, supporting force called the normal force. If you slide a book across a table, the table exerts a frictional force against the book, so the book slows down and eventually stops. Static cling provides a simple example of the electrostatic force. (In fact, all of the forces mentioned above, with the exception of gravity, are due ultimately to the electromagnetic force.)

Newton’s First Law

An object’s state of motion—its velocity—will not change unless a net force acts on the object.

That is, if no net force acts on an object, then:

if the object is at rest, it will remain at rest;

and

if the object is moving, then it will continue to move with constant velocity

(constant speed in a straight line).

Or, more simply: no net force = no acceleration.

How forces affect motion is described by three physical laws, known as Newton’s laws. They form the foundation of mechanics, and you should memorize them.

The first law says that objects naturally resist changing their velocity. In other words, objects at rest don’t just suddenly start moving all on their own. Some external source must exert a force to make them move. Also, an object that’s already moving doesn’t change its velocity. It doesn’t go faster, or slower, or change direction all by itself; something must exert some force on it to make any of these changes happen. This property of objects, their natural resistance to change in their state of motion, is called inertia. In fact, the first law is often referred to as the law of inertia.

It’s important to note that the first law applies when there is no net force on an object. This could mean there are no forces at all, though that couldn’t happen in our universe; more commonly, it means the forces on an object balance out, in other words, the total of all the forces, in each dimension, is zero. We’ll work examples of computing net force when we get to Newton’s second law.

The mass of an object is the quantitative measure of its inertia; intuitively, mass measures how much matter is contained in an object. Mass is measured in kilograms, abbreviated kg. (Note: An object whose mass is 1 kg weighs a little more than 2 pounds on Earth, but be careful not to confuse mass with weight; they’re different things.) Compared to an object whose mass is just 1 kg, an object whose mass is 100 kg has 100 times the inertia. Intuitively, we’d find it 100 times more difficult to cause the same change in its motion than we would with the 1 kg object. This point will be clearer after we state the second of Newton’s laws.

Newton’s Second Law

If Fnet is the net—or total—force acting on an object of mass m, then the resulting acceleration of the object, a, satisfies this simple equation:

Fnet = ma

Notice that the first law is really just a special case of the second law: the case in which Fnet = 0.

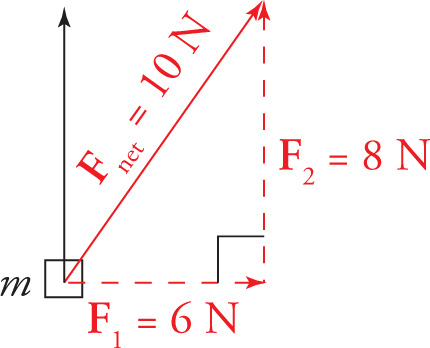

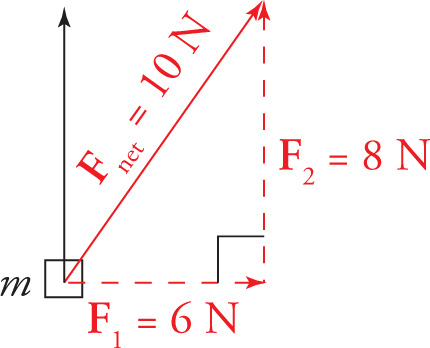

Forces are represented by vectors, because a force has a magnitude and a direction. If two different forces (let’s call them F1 and F2) act on an object, then the total—or net—force on the object is the sum of these individual forces: Fnet = F1 + F2. Since forces are vectors, they must be added as vectors; that is, their directions must be taken into account. The following figures show some examples of obtaining Fnet from the individual forces that act on an object:

Note the following facts about the equation Fnet = ma:

1. Fnet is the sum of all the forces that act on the object; namely, the object whose mass, m, is on the other side of the equation. Any force exerted by the object is not included in Fnet.

2. Because m is a positive number, the direction of a is always the same as the direction of Fnet. Therefore, an object will accelerate in the direction of the net force it feels. This does not mean that an object will always move in the direction of Fnet. Be sure that this distinction makes sense, because it can be a source of confusion, and therefore a potential MCAT trap. Newton’s second law tells us about the direction of an object’s acceleration but does not define the direction of an object’s velocity.

3. What if Fnet = 0? Then a = 0. What does a = 0 mean? It means that the object’s velocity does not change, which is also what Newton’s first law says. But how about this question: Does Fnet = 0 mean that v = 0? Not necessarily! Fnet = 0 means that an object won’t accelerate, not that it won’t move. This is a key point and another potential MCAT trap. If the object is already moving at, say, 100 m/s toward the north, then it will continue to move at 100 m/s toward the north as long as the net force on the object remains zero.

4. Because Fnet = ma is a vector equation, it automatically means that the components of both sides must be the same. In other words, Fnet could be written as the sum of a force in the horizontal direction, (Fnet, x) plus a force in the vertical direction (Fnet, y); these would be the horizontal and vertical components of Fnet. The equation Fnet = ma would then tell us that Fnet, x = ma x and Fnet, y = ma y. So, dividing the horizontal component of the net force by m gives us the horizontal component of the object’s acceleration, and dividing the vertical component of the net force by m gives us the vertical component of the object’s acceleration.

5. The unit of force is equal to the unit of mass times the unit of acceleration:

[F] = [m][a] = kg · m/s2

A force of 1 kg·m/s2 is called 1 newton (abbreviated N). A force of 1 N is about equal to a quarter of a pound, or about the weight of a medium-sized apple (on Earth).

Newton’s Third Law

If Object 1 exerts a force, F1-on-2, on Object 2, then Object 2 exerts a force, F2-on-1, on Object 1. These forces, F1-on-2 and F2-on-1, have the same magnitude but act in opposite directions, so

F1-on-2 = –F2-on-1

and they act on different objects. These two forces are said to form an action–reaction pair.

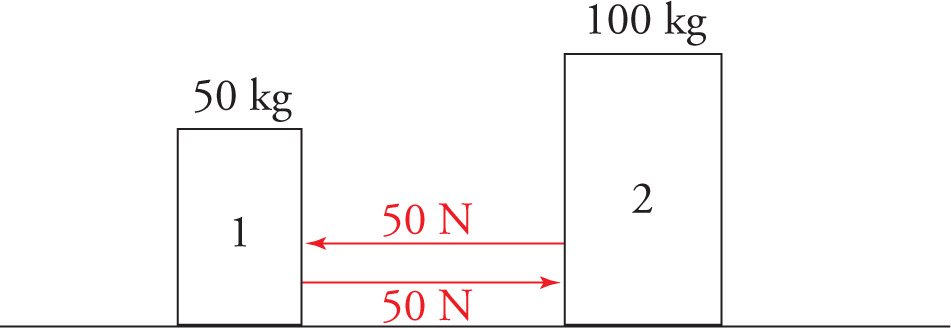

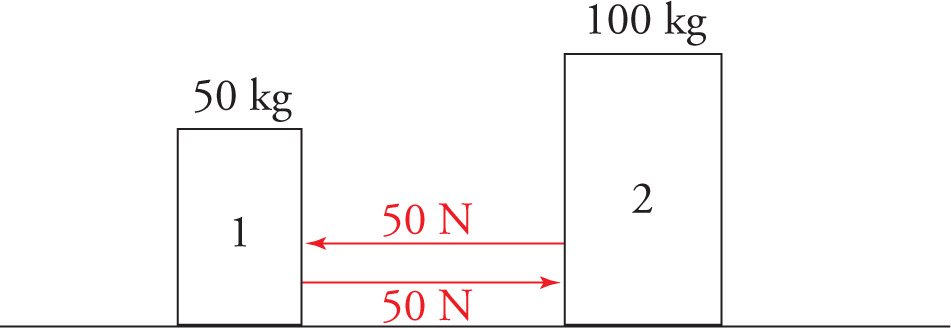

This is the law commonly stated as, “For every action, there is an equal but opposite reaction.” Unfortunately, this popular version of Newton’s third law can lead to confusion. Essentially, Newton’s third law says that the forces in an action–reaction pair have the same magnitude and act in opposite directions (and on “opposite” objects). It does not say that the effects of these forces will be the same. For example, suppose that two skaters are next to and facing each other on a skating rink. Let’s say that Skater 1 has a mass of 50 kg and Skater 2 has a mass of 100 kg. Now, what if Skater 1 pushes on Skater 2 with a force of 50 N? Then F1-on-2 = 50 N and F2-on-1 = –50 N, by Newton’s third law.

But will the effects of these equal-strength forces be the same? No, because the masses of the objects are different. The accelerations of the skaters will be

and

So, Skater 2 will move away with an acceleration of 0.5 m/s2, while Skater 1 moves away, in the opposite direction, with an acceleration of twice that magnitude, 1 m/s2.

Therefore, while the forces are the same (in magnitude), the effects of these forces —that is, the resulting accelerations (and velocities)—are not the same, because the masses of the objects are different. Newton’s third law says nothing about mass; it only tells us that the action and reaction forces will have the same magnitude. So, the point is not to interpret “equal but opposite reaction” as meaning “equal but opposite effect,” because if the masses of the interacting objects are not the same, then the resulting accelerations (and velocities) of the objects will not be the same.

The key to distinguishing Newton’s first law from Newton’s third law is to focus on the description of the forces. In Newton’s first law, all of the forces must be acting on a single object; thus, the net force on a single object is calculated by adding those vectors. However, in Newton’s third law, each force must be acting on a different object in an action-reaction pair.

There are two aspects of Newton’s third law that frequently give students trouble. First, just because two forces are equal and opposite does not mean they form an action-reaction pair; the forces also have to be from two objects acting on each other, not two objects acting on a third object. Second, the third law applies even when the objects are accelerating; even if one object is accelerating, the second object pushes or pulls just as hard on the first as the first pushes or pulls on the second.

Example 4-1: An object of mass 50 kg moves with a constant velocity of magnitude 1000 m/s. What is the net force on this object?

Solution: If the object moves with constant velocity, then the net force it feels must be zero, regardless of the object’s mass or speed.

Example 4-2: The net force on an object of mass 10 kg is zero. What can you say about the speed of this object?

Solution: If the net force on an object is zero, all we can say is that it will not accelerate; its velocity may be zero, or it may not. Without more information, we cannot determine the object’s speed; all we know is that whatever the speed is, it will remain constant.

Example 4-3: For 6 seconds, you push a 120 kg crate along a frictionless horizontal surface with a constant force of 60 N parallel to the surface. If the crate was initially at rest, what will its velocity be at the end of this 6-second time interval?

Solution: Using Newton’s second law, we find that the acceleration of the crate is a = F/m = (60 N)/(120 kg) = 0.5 m/s2. Using Big Five #2, we now find that v = v0 + at = 0 + (0.5 m/s2)(6 s) = 3 m/s.

Example 4-4: For 6 seconds, you pull a 120 kg crate along a frictionless horizontal surface with a constant force of 60 N directed at an angle of 60° to the surface. If the crate was initially at rest, what will its horizontal velocity be at the end of this 6-second time interval?

Solution: To find the horizontal velocity, we need the horizontal acceleration.

Using Newton’s second law, we find that the horizontal acceleration of the crate is ax = Fx/m = (F cos θ)/m = (60 N)(cos 60°)/(120 kg) = (30 N)/(120 kg) = 0.25 m/s2. Using Big Five #2, we now find that vx = v0x + axt = 0 + (0.25 m/s2)(6 s) = 1.5 m/s.

Example 4-5: Two crates are moving along a frictionless horizontal surface. The first crate, of mass M = 100 kg, is being pushed by a force of 300 N. The first crate is in contact with a second crate, of mass m = 50 kg.

a) What’s the acceleration of the crates?

b) What’s the force exerted by the larger crate on the smaller one?

c) What’s the force exerted by the smaller crate on the larger one?

Solution:

a) The force F is pushing on a combined mass of 100 kg + 50 kg = 150 kg, so by Newton’s second law, the acceleration of both crates will be a = (300 N)/(150 kg) = 2 m/s2.

b) Because M and m are in direct contact, each is pushing on the other with a certain force. Let F2 be the force that M exerts on m. Then we must have F2 = ma, so F2 = (50 kg)(2 m/s2) = 100 N.

c) By Newton’s third law, if the force that M exerts on m is F2, then the force that m exerts on M must be –F2. So, if we call “to the right” our positive direction, then the force that m exerts on M is –100 N. We can check that this is correct by looking at all the forces acting on M. We have F pushing to the right and –F2 pushing to the left. The net force on M is therefore Fnet on M = F + (–F2) = (300 N) + (–100 N) = 200 N. If this is correct, then Fnet on M should equal Ma. Since M = 100 kg and a = 2 m/s2, we get Ma = 200 N, which does match what we found for Fnet on M. (In effect, what’s happening here is that M is using 200 N of the 300 N force from F for its own motion and passing the remaining 100 N along to m, so that both move together with the same acceleration.)

Example 4-6: Two forces act on an object of mass m = 5 kg. One of the forces has a magnitude of 6 N, and the other force, perpendicular to the first, has a magnitude of 8 N. What’s the acceleration of the object?

Solution: Forces are vectors, and when we find the net force on this object, we see that it’s the hypotenuse of a 6-8-10 right triangle.

Since Fnet = 10 N, the acceleration of the object will be a = Fnet/m = (10 N)/(5 kg) = 2 m/s2.

Example 4-7: The figure below shows all the forces acting on a 5 kg object. The magnitude of F1 is 50 N. If the acceleration of the object is 8 m/s2, what’s the magnitude of F2?

Solution: The net force on the block is just the sum of F1 and F2, so Fnet = F1 + F2 = (+50 N) + F2, if we call “to the right” our positive direction. The net force must be ma = (5 kg)(8 m/s2) = 40 N. Since (+50 N) + F2 must be 40 N, we know that F2 = –10 N; that is, F2 has magnitude 10 N (and points to the left).

Example 4-8: According to Newton’s third law, every force is “accompanied by” an equal but opposite force. If this is true, shouldn’t these forces cancel out to zero? How could we ever accelerate an object?

Solution: The answer does not involve the masses of the objects; Newton’s third law says nothing about mass. The key is to remember what Fnet means; it’s the sum of all the forces that act on an object, not by the object. Let’s say we have a pair of objects, 1 and 2, and an action–reaction pair of forces between them, and we wanted to find the acceleration of Object 2. We’d find all the forces that act on Object 2. One of these forces is F1-on-2. The reaction force, F2-on-1, is not included in Fnet-on-2 because it doesn’t act on Object 2; it’s a force by Object 2. So, the reason why the two forces in an action–reaction pair don’t cancel each other is that we’d never add them in the first place because they don’t act on the same object.

The mass of an object is a measure of its inertia, its resistance to acceleration. We’ll now look at the related concept of an object’s weight.

Although in everyday language the terms mass and weight are sometimes used interchangeably, in physics they have very different technical meanings. The weight of an object is the gravitational force exerted on it by the earth (or by whatever planet it happens to be on or near). Mass is an intrinsic property of an object and does not change with location. Put a baseball in a rocket and send it to the moon. The baseball’s weight on the moon is less than its weight here on Earth, but you’d have as much “baseball stuff” there as you would here; that is, the baseball’s mass would not change.

Since weight is a force, we can use F = ma to compute it. What acceleration would the gravitational force (which is what weight means) impose on an object? The gravitational acceleration, of course! Therefore, setting a = g, the equation F = ma becomes

w = mg

This is the equation for the weight, w, of an object of mass m. (Weight is often symbolized by Fgrav, rather than w; we’ll use both notations.) Note that mass and weight are proportional but not identical. Furthermore, mass is measured in kilograms, while weight is measured in newtons.

Example 4-9:

a) Find the weight of an object whose mass is 50 kg.

b) Find the mass of an object whose weight is 50 N.

Solution:

a) To find an object’s weight, we multiply its mass by g. Using g = 10 m/s2 (or, equivalently, g = 10 N/kg), we find that w = mg = (50 kg)(10 N/kg) = 500 N.

b) To find an object’s mass, we divide its weight by g. With g = 10 N/kg, we find that m = w/g = (50 N)/(10 N/kg) = 5 kg.

Most of the time, we’ll use the formula w = mg to find the weight of an object whose mass is m. However, the value of g can change, and if we’re not near the surface of Earth (where we know that g is approximately 10 m/s2), we may not know the value of g. In that case, we’ll invoke another law discovered by Newton:

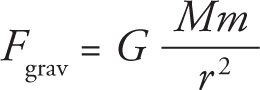

Every object in the universe exerts a gravitational pull on every other object. The magnitude of this gravitational force is proportional to the product of the objects’ masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. The constant of proportionality is denoted by G and known as Newton’s universal gravitational constant.

The value of G is roughly 6.7 × 10–11 N·m2/kg2, but don’t bother memorizing this constant. If you actually need the value on the MCAT (which is unlikely), it will be provided. Unfortunately, sometimes it will be provided even when you don’t need it.

One of the most important features of Newton’s law of gravitation is that it’s an inverse-square law. This means that the magnitude of the gravitational force is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the centers of the objects. (Another important physical law, Coulomb’s law [for the electrostatic force between two charges], which we’ll see later, is also an inverse-square law.)

Also notice that the forces illustrated in the box above form an action–reaction pair. Even if M and m are different, the gravitational force that M exerts on m has the same magnitude as the gravitational force that m exerts on M. (If the directions of the force vectors in the box above seem backward, remember that gravity is always a pulling force; therefore, in the figure above, FM-on-m pulls to the left, toward M, while Fm-on-M pulls to the right, toward m.) Of course, the accelerations of the objects will have different magnitudes if the masses are different, as we discussed earlier when we studied Newton’s third law.

Example 4-10: What will happen to the gravitational force between two objects if the distance between them is doubled? What if the distance is cut in half?

Solution: Since the gravitational force obeys an inverse-square law, if r increases by a factor of 2, then Fgrav will decrease by a factor of 22 = 4. On the other hand, if r decreases by a factor of 2, then Fgrav will increase by a factor of 22 = 4.

Notice that the two formulas given in this section, w = mg and Fgrav = GMm/r2, are really formulas for the same thing. After all, weight is gravitational force. Therefore, we could set these expressions equal to each other:

mg = G

![]()

Then, dividing both sides by m, we get

g = G

![]()

This formula tells us how to find the value of the gravitational acceleration, g. On Earth, we know that g ≈ 10 m/s2. If we were to go to the top of a mountain, then the distance r to the center of the earth would increase, but compared to the radius of the earth, the increase would be very small. As a result, while the value of g is less at the top of a mountain than at the earth’s surface, the difference is small enough that it can usually be neglected. However, at the position of a satellite orbiting the earth, for example, the distance to the center of the earth has now increased dramatically (for example, many satellites have an orbit radius that’s over 6.5 times the radius of the earth), and the resulting decrease in g would definitely need to be taken into account.

This formula for g also shows us why g changes from planet (or moon) to planet. For example, on Earth’s moon, the value of g is only about 1.6 m/s2 (about a sixth of what it is on Earth) because the mass of the moon is so much smaller than the mass of the earth. It’s true that the radius of the moon is smaller than the radius of the earth, which would, by itself, make g bigger, but M is much smaller, and this is why the value of g on the surface of the moon is smaller than its value on the surface of the earth. So, while big G is a universal gravitational constant, the value of little g depends on where you are.

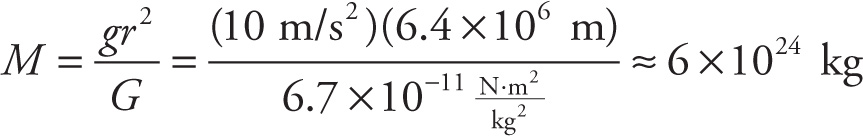

Example 4-11: The radius of Earth is approximately 6.4 × 106 m. What’s the mass of Earth?

Solution: We can use the formula g = GM/r2 to solve for M:

Example 4-12: The mass of Mars is about 1/10 the mass of Earth, and the radius of Mars is about half that of Earth. Is the value of g on the surface of Mars less than, greater than, or equal to the value of g on Earth?

Solution: We’ll use the formula g = GM/r2 to compare the two values of g:

Therefore, the value of g on Mars is only about 40% of its value here.

Example 4-13: A long, flat, frictionless table is set up on the surface of the moon (where g = 1.6 m/s2). An object whose mass on Earth is 4 kg is also transported there.

a) What is the object’s mass on the moon?

b) What is the object’s weight on the moon?

c) If we drop this object from a height of h = 20 m, with what speed will it strike the lunar surface?

d) If we wish to push this object across the table to give it an acceleration of 3 m/s2, how much force must we exert? Would this force be different if the table and object were back on Earth?

Solution:

a) The mass is the same, 4 kg.

b) The weight of the object on the moon is w = m·gmoon = (4 kg)(1.6 m/s2) = 6.4 N. Notice that the object’s weight on the moon is different from its weight on Earth.

c) Calling down the positive direction and using Big Five #5 with v0= 0 and a = gmoon = 1.6 m/s2, we find that

d) Using F = ma, we get F = (4 kg)(3 m/s2) = 12 N. Since Newton’s second law depends only on mass (not on weight, because there’s no g in Newton’s second law), we’d need this same force even if the object and table were back on Earth.

Example 4-14: A satellite is orbiting Earth at an altitude equal to 3 times Earth’s radius. If the satellite weighs 144,000 N on the surface of Earth, what is the gravitational force on the satellite while it’s in orbit?

Solution: Let R be the radius of Earth. If the satellite’s altitude, h, is 3R, then its distance from the center of Earth is R + h = R + 3R = 4R. Therefore, the distance from Earth’s center has increased by a factor of 4, not 3. Since Newton’s law of gravitation is an inverse-square law, the fact that r has increased by a factor of 4 means that Fgrav has decreased by a factor of 42 = 16. The gravitational force on the satellite while it’s in orbit is therefore

![]() (144,000N) = 9,000N.

(144,000N) = 9,000N.

Some of the examples in the preceding sections described a frictionless surface. Of course, there’s no such thing as a truly frictionless surface, but when a problem uses a term like frictionless, it simply means that friction is so weak that it can be neglected. Having frictionless surfaces also made those examples easier, so we could become comfortable with Newton’s laws while first learning to apply them. However, there are cases in which friction cannot be ignored, so we need to learn how to handle such situations.

When two materials are in contact, there’s an electrical attraction between the atoms of one surface with those of the other; this attraction will make it difficult to slide one object relative to the other. In addition, if the surfaces aren’t perfectly smooth, the roughness will also increase the force required to slide the objects against each other. Friction is the term we use for the combination of these effects. Fortunately, the forces due to all those intermolecular forces and to the interactions of surface irregularities can be expressed by a single equation.

The MCAT will expect you to know about two big categories of friction; they’re called static friction and kinetic (or sliding) friction.1 When there’s no relative motion between the surfaces that are in contact (that is, when there’s no sliding) we have static friction; when there is relative motion between the surfaces (that is, when there is sliding) we have kinetic friction.

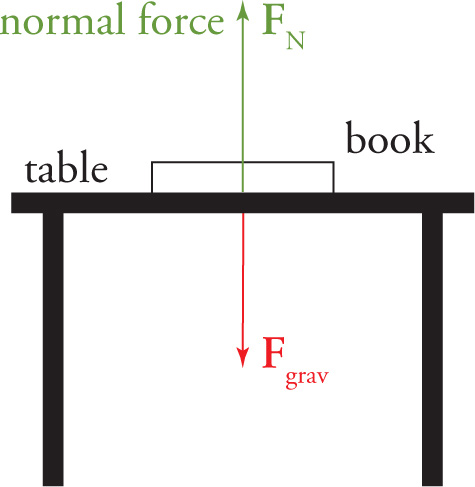

Now, in order to state the equations we’ll use to figure out these frictional forces, we first need to discuss another contact force, the one known as the normal force.

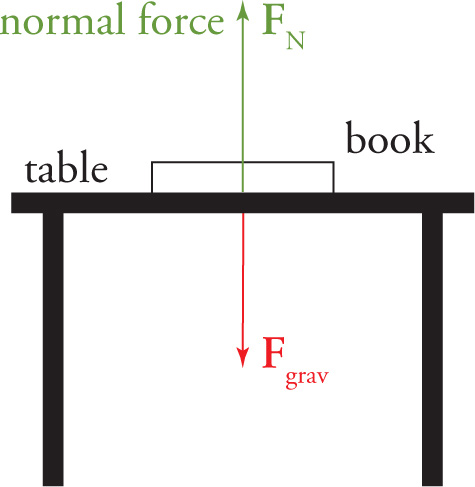

Place a book on a flat table. Assuming that the book isn’t too heavy and the tabletop isn’t made of, say, tissue paper, the book will remain supported by the table. One force acting on the book is the downward gravitational force. If this were the only force acting on the book, then the book would fall through the table. Hence, there must be an upward force acting on the book that cancels out the book’s weight. This supporting force, which acts perpendicular to the tabletop, is called the normal force. It’s called the normal force because it is, by definition, perpendicular to the surface that exerts it. The word normal means perpendicular. We’ll denote the normal force by N or by FN. [Don’t confuse N (or its magnitude, N) with the abbreviation for the newton, N.] In the case of an object simply lying on a flat surface, the magnitude of the normal force is just equal to the object’s weight. As a result, the book feels a downward force of magnitude w = mg and an upward force of magnitude N = mg, so the net force on the book is 0.

Example 4-15: Do the normal force and the gravitational force described in the preceding paragraph form an action–reaction pair?

Solution: No. While these forces are equal but opposite, they do not form an action–reaction pair, because they act on the same object (namely, the book). The forces in an action–reaction pair always act on different objects. So, while it’s true that the forces in an action–reaction pair are always equal but opposite, it is not true that any pair of equal but opposite forces must always form an action–reaction pair. The reaction force to Ftable-on-book, which is the normal force, is Fbook-on-table. The reaction force to FEarth-on-book, which is the weight of the book, is Fbook-on-Earth. The force Ftable-on-book is not the reaction to FEarth-on-book.

For an object on a horizontal surface that feels no other downward forces, the normal force will be equal to the weight of the object. However, there are many cases in which the normal force isn’t equal to the weight of the object. For example, suppose we place a book against a vertical wall and push on the book with a horizontal force F. Then the magnitude of the normal force exerted by the wall will be equal to F, which may certainly be different from the weight of the book. Here’s another example (which we’ll look at in more detail in the next section): If we place a book on an inclined plane (e.g., a ramp), then the normal force exerted by the ramp on the book will not be equal to the weight of the book. What we can say is the general definition of the normal force: The normal force is the perpendicular component of the contact force exerted by a surface on an object.

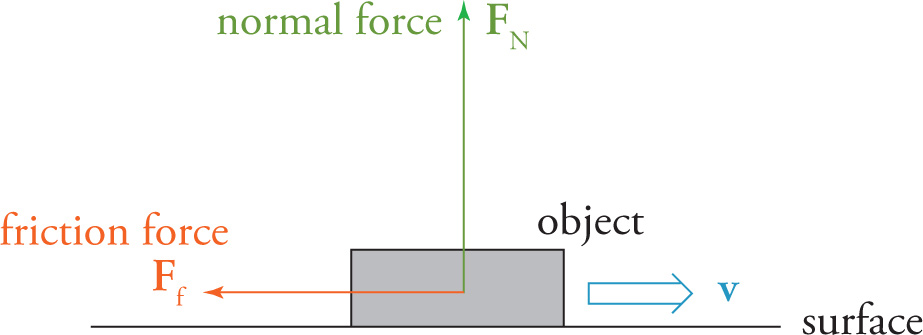

We had to discuss the normal force here, because the force of friction exerted by a surface on an object in contact with is related to the normal force. In the case of sliding (kinetic) friction, the magnitude of the force of friction is directly proportional to the magnitude of the normal force. The constant of proportionality depends on what the surface is made of and what the object is made of; this constant is called the coefficient of kinetic friction, denoted by µk (the Greek letter mu, with subscript k), where the k denotes kinetic friction. For every pair of surfaces, the coefficient µk is an experimentally determined positive number with no units, and the greater its value, the greater the force of kinetic friction. For example, the value of µk for rubber-soled shoes on ice is only about 0.1, while for rubber-soled shoes on wood, the value of µk is much higher; it’s about 0.7 for your sneakers, but could be greater than 1 if you walk around in rock-climbing shoes.

Notice carefully that this is not a vector equation. It is only an equation giving the magnitude of Ff in terms of the magnitude of FN.

Force of Kinetic Friction

Ff = µk FN

The magnitude of the force of kinetic friction is given by the equation Ff = µkFN. The direction of the force of kinetic friction is always parallel to the surface and in the opposite direction to the object’s velocity (relative to the surface).

Example 4-16: A book of mass m = 2 kg slides across a flat tabletop. If the coefficient of kinetic friction between the book and table is 0.4, what’s the magnitude of the force of kinetic friction on the book?

Solution: Because the magnitude of the normal force is FN = mg = (2 kg)(10 m/s2) = 20 N, the magnitude of the force of kinetic friction is Ff = µkFN = (0.4)(20 N) = 8 N.

The formula for static friction is similar to the one for kinetic friction, but there are two important differences. First, given a pair of surfaces, there’s a maximum coefficient of static friction between them, µs (the subscript s now denotes static friction), and on the MCAT, it’s always greater than the coefficient of kinetic friction. This is equivalent to saying that, in general, static friction is capable of being stronger than kinetic friction. To illustrate this, imagine there’s a heavy crate sitting on the floor and you want to push the crate across the room. You walk up to the crate and push on it, harder and harder until, finally, it “gives” and starts sliding. Once the crate is sliding, it’s easier to keep it sliding than it was to get it started in the first place. The friction that resisted your initial push to get the crate moving was static friction. Because it was easier to keep it sliding than it was to get it started sliding, kinetic friction must be weaker than the maximum static friction force.

The second difference between the formula for kinetic friction and the one for static friction is that there’s actually no general formula for the force of static friction. All we have is a formula for the maximum force of static friction. It’s important that you understand this distinction. Let’s go back to that heavy crate sitting on the floor. Let’s say you know by previous experience that it’ll take 400 N of force on your part to get that crate sliding. So, what if you push with a force of 100 N? Well, obviously, the crate won’t move. Therefore, there must be another 100 N acting on the crate, opposite to your push, to make the net force on the crate zero. Okay, what if you now push on the crate with a force of 200 N? The crate still won’t move, so there must now be another 200 N acting on the crate, opposite to your push, to make the net force on the crate zero. Whatever force you exert on the crate, as long as it’s less than 400 N, will cause the force of static friction to cancel you out. Static friction is capable of supplying any necessary force, but only up to a certain maximum. That’s why we can’t write down a general formula for the force of static friction, only a formula for the maximum force of static friction. The formula looks just like the one above, except we replace µk by µs, and add the word “max” to denote that all this formula gives is the maximum force of static friction.

Maximum Force of Static Friction

Ff, max = µs FN

The maximum magnitude of the force of static friction is given by the equation Ff, max = µsFN. The direction of the force of static friction (maximum or not) is always parallel to the surface and in the opposite direction to the object’s intended velocity. The magnitude of the force of static friction is whatever value, up to the maximum given by the equation, it takes exactly to cancel out the force(s) that are trying to make the object slide.

Example 4-17: A crate that weighs 1000 N rests on a horizontal floor. The coefficient of static friction between the crate and the floor is 0.4. If you push on the crate with a force of 250 N, what is the magnitude of the force of static friction?

Solution: The answer is not 400 N. The maximum force of static friction that the floor could exert on the crate is Ff, max = µsFN = (0.4)(1000 N) = 400 N. However, if you exert a force of only 250 N on the crate, then static friction will only be 250 N. (Just imagine what would happen to the crate if you pushed on it with a force of 250 N and the floor pushed it back toward you with a force of 400 N!)

Example 4-18: You push a 50 kg block of wood across a flat concrete driveway, exerting a constant force of 300 N. If the coefficient of kinetic friction between the wood and concrete is 0.5, what will be the acceleration of the block?

Solution: The normal force acting on the block has a magnitude of FN = mg = (50 kg)(10 m/s2) = 500 N. Therefore, the force of kinetic friction acting on the sliding block has a magnitude of Ff = µkFN = (0.5)(500 N) = 250 N. This means that the net force acting on the block (and parallel to the driveway) is equal to F – Ff = (300 N) – (250 N) = 50 N. If Fnet = 50 N and m = 50 kg, then a = Fnet/m = (50 N)/(50 kg) = 1 m/s2.

Example 4-19: Instead of pushing the block by a force that’s parallel to the driveway, you wrap a rope around the block, sling the rope over your shoulder, and walk it across the driveway. If the rope makes an angle of 30° to the horizontal, and the tension in the rope is 300 N (the same force you exerted on the block in the last example), what will the block’s acceleration be now?

Solution: This is a tough question, but it uses a lot of the material we’ve covered so far. First, we’ll need the normal force to find the friction force. The net vertical force on the block is 0 (because we’re not lifting the block off the ground or watching it fall through the concrete). Therefore, FN + Fy = Fgrav, so FN = Fgrav – Fy. (Here’s another example of the normal force not equaling the weight of the object.) Since Fy = F sin θ = F sin 30° = (300 N)(0.5) = 150 N, we have FN = (500 N) – (150 N) = 350 N. (Intuitively, the normal force is less than the weight of the block because the vertical component of the tension in the rope is “taking some of the pressure” off the surface.) Therefore, Ff = µkFN = (0.5)(350 N) = 175 N. Now, the horizontal force that you provide is Fx = F cos θ = F cos 30° ≈ (300 N)(0.85) = 255 N. Therefore, the net force acting on the block, parallel to the driveway, is equal to Fx – Ff = (255 N) – (175 N) = 80 N. If Fnet = 80 N and m = 50 kg, then a = Fnet/m = (80 N)/(50 kg) = 1.6 m/s2. (Notice that you get the block moving faster—even exerting the same force—by doing it this way!)

So far, we’ve had practice problems where the object is moving along a flat, horizontal surface. However, the MCAT will also expect you to handle questions in which the object is on a ramp, or, in fancier language, an inclined plane.

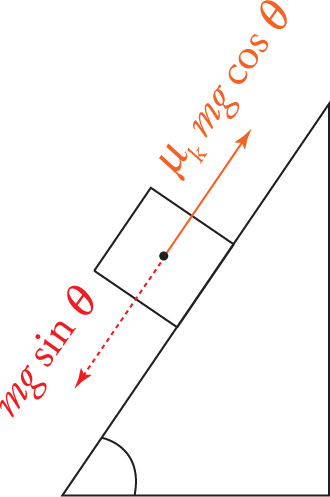

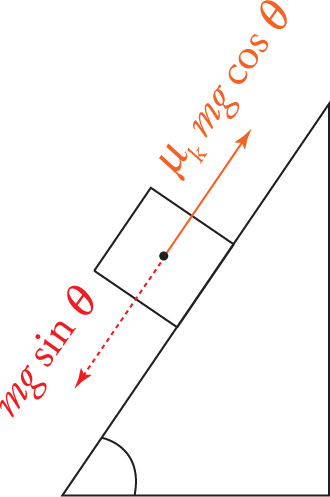

The figure below shows an object of mass m on an inclined plane; the angle the plane makes with the horizontal (the incline angle) is labeled θ. If we draw the vector representing the weight of the object, we notice that it can be written in terms of two components: one parallel to the ramp and one perpendicular to it. The diagram on the left shows that the magnitudes of the components of the object’s weight, w = mg, are mg sin θ (parallel to the ramp) and mg cos θ (perpendicular to the ramp).

Therefore, as illustrated in the diagram on the right,

the force due to gravity acting parallel to the inclined plane = mg sin θ

where θ is measured between the incline and horizontal. You should memorize both of these facts.

Incidentally, any time we see an angle in an MCAT problem we’ll probably be breaking a vector (say a force, a velocity, or an acceleration) into components. When we looked at projectile motion we broke the projectile’s initial velocity into horizontal and vertical components; here, we’re breaking the force of gravity into a component parallel to and one perpendicular to the surface of the incline. Why the difference? In general, the components you’ll use will be vertical and horizontal, unless the object can only move along one possible line; in that case, the components to use will be the direction of (possible) travel (in this case, parallel to the incline) and, the direction perpendicular to that.

Example 4-20: A block of mass m = 4 kg is placed at the top of a frictionless ramp of incline angle 30° and length 10 m.

a) What is the block’s acceleration down the ramp?

b) How long will it take for the block to slide to the bottom?

Solution:

a) Because the force due to gravity acting parallel to the ramp is F = mg sin θ, the acceleration of the block down the ramp will be

b) Using Big Five #3 with d = 10 m, v0 = 0, and a = 5 m/s2, we find that

Notice that the block’s mass was irrelevant to both of these questions. That’s because all of the forces were directly proportional to mass, but so was the object’s inertia; in effect, mass cancelled out of both sides of F = ma. This is common in problems in which the forces on an object are all functions of gravity.

Example 4-21: A block of mass m slides down a ramp of incline angle 60°. If the coefficient of kinetic friction between the block and the surface of the ramp is 0.2, what’s the block’s acceleration down the ramp?

Solution: There are now two forces acting parallel to the ramp: mg sin θ (directed downward along the ramp) and Ff, the force of kinetic friction (directed upward along the ramp). Therefore, the net force down the ramp is Fnet = mg sin θ – Ff. To find Ff, we multiply FN by µk. Since FN = mg cos θ, we have

Fnet = mg sin θ − µk mg cos θ

Dividing Fnet by m gives us a:

Putting in the numbers, we get

a = (10 m/s2)(sin 60° − 0.2 cos 60°) ≈ (10 m/s2)(0.85−0.2·

![]() ) = 7.5 m/s2

) = 7.5 m/s2

Example 4-22: A block of mass m is placed on a ramp of incline angle θ. If the block doesn’t slide down, find the relationship between µs (the coefficient of static friction) and θ.

Solution: If the block doesn’t slide, then static friction is strong enough to withstand the pull of gravity acting downward parallel to the ramp. This means that the maximum force of static friction must be greater than or equal to mg sin θ. Since Ff (static), max = µsFN, and FN=mg cos θ, we have Ff (static), max = µsmg cos θ. Therefore,

Ff (static) max ≥ mg sin θ

µs mg cos θ ≥ mg sin θ

µs g cos θ ≥ g sin θ

µs ≥

![]()

∴ µs ≥ tan θ

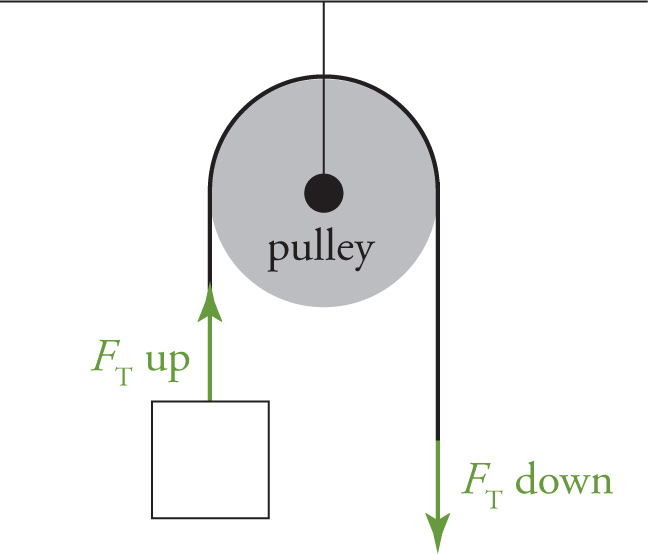

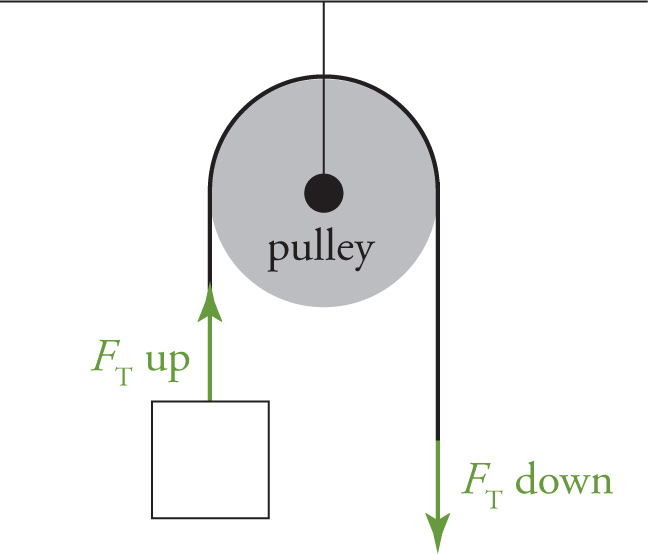

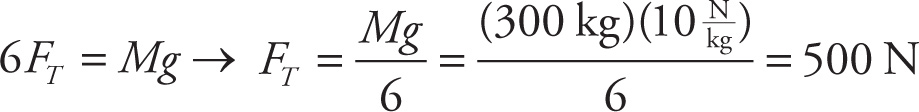

A pulley is a device that changes the direction of the tension (the force exerted by a stretched string, cord, or rope) that pulls on the object that the string is attached to. (We’ll use FT or T to denote a tension force.) For example, in the picture below, if we pull down on the string on the right with a force of magnitude FT, then the tension force on the left side of the pulley will pull up on the block with the same magnitude of force, FT.

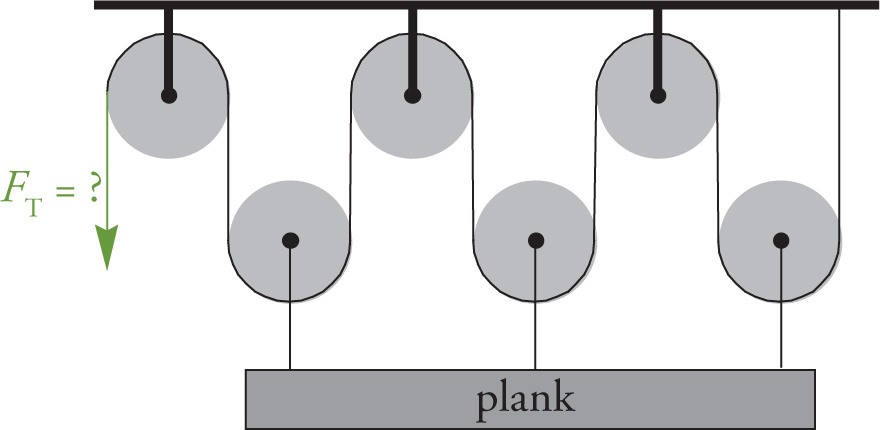

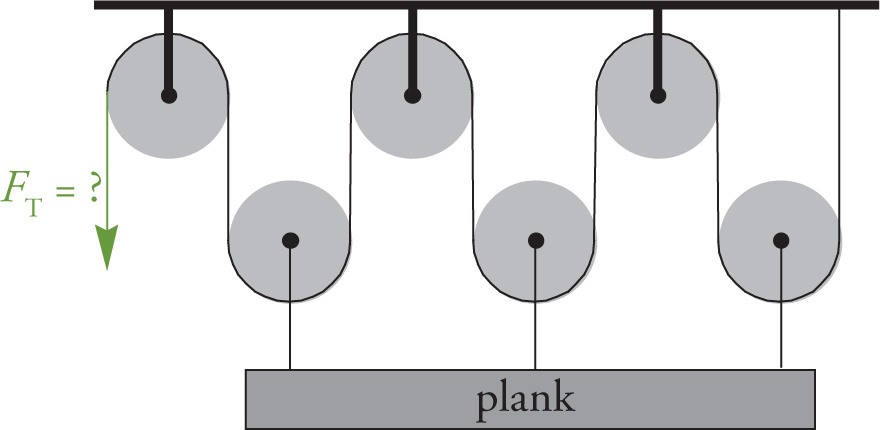

Pulleys can also be used to decrease the force necessary to lift an object. For example, consider the pulley system illustrated on the left below. If we pull down on the string on the right with a force of magnitude FT, then we’ll create a tension force of magnitude FT throughout the entire string. As a result, there will be two tension forces, each of magnitude FT, pulling up to lift the block (and the bottom pulley, too, but we assume that the pulleys are massless; that is, the mass of any pulley is small enough that it can be ignored). Therefore, we only need to exert half as much force to lift the block! This simple observation, that a pulley system (with massless, frictionless pulleys) causes a constant tension to exist through the entire string, which can lead to multiple tension forces pulling on an object, is the key to many MCAT problems on pulleys.

Pulley systems like this multiply our force by however many strings are pulling on the object.

Notice carefully that the tension force is applied wherever a string (or rope, or cable, or whatever) comes in contact with a pulley, which means that there will often be two tension forces on a single pulley, one on each side. You can see this in the right-hand diagram above.

Example 4-23: In the figure below, how much force would we need to exert on the free end of the cord in order to lift the plank (mass M = 300 kg) with constant velocity? (Ignore the masses of the pulleys.)

Solution: As a result of our pulling downward, there will be 6 tension forces pulling up on the plank:

In order to lift with constant velocity (acceleration = zero), we require the net force on the plank to be zero. Therefore, the total of all the tension forces pulling up, 6FT, must balance the weight of the plank downward, Mg. This gives us

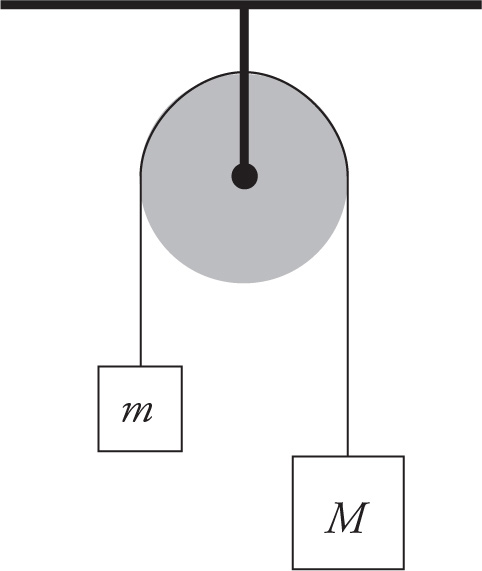

Example 4-24: Two blocks are connected by a cord that hangs over a pulley. One block has a mass, M, of 10 kg, and the other block has a mass, m, of 5 kg. What will be the magnitude of the acceleration of the system of blocks once they are released from rest?

Solution: We’ll solve this by a step-by-step approach using a force diagram. To apply Newton’s second law, Fnet = ma, to any problem, we follow these steps:

Step 1: Draw all the forces that act on the object. (That is, draw the force diagram.)

Step 2: Choose a direction to call positive (simply take the direction of the object’s motion to be positive; it’s almost always the easiest, most natural decision).

Step 3: Find Fnet and set it equal to ma.

We have effectively done these steps in the solutions to the examples we have seen already, but now that we have a situation involving two accelerating objects, it is even more important to make sure that we have a systematic plan of attack. When you have more than one object to worry about, just make sure that the Step-2 decision you make for one object is compatible with the Step-2 decision you make for the other one(s). On the left below are the force diagrams for the blocks on the pulley. Notice that we call up the positive direction for m (because that’s where it’s going), and we call down the positive direction for M (because that’s where it’s going); these decisions are compatible, because when m moves in its positive direction, so does M.

Because up is the positive direction for little m, the force FT on m is positive and the force mg is negative; therefore, for little m, we have Fnet = FT + (–mg) = FT – mg. Since down is the positive direction for big M, the force Mg on M is positive and the force FT is negative; therefore, for big M, we have Fnet = Mg + (–FT) = Mg – FT. On the right above, we’ve written down Fnet = mass × acceleration for each block. There are two equations, but we have two unknowns (FT and a), so we need two equations. To solve the equations, the trick is simply to add the equations. Notice that this makes the FT’s drop out, so all we’re left with is one unknown, a, which we can solve for immediately. The calculation shown above gives a = g/3, so we get a = 3.3 m/s2.

If the question had asked for the tension in the cord, we could now use the value we found for a and plug it back into either of our two equations (we’d get the same answer no matter which one we used). Using FT – mg = ma, we’d find that

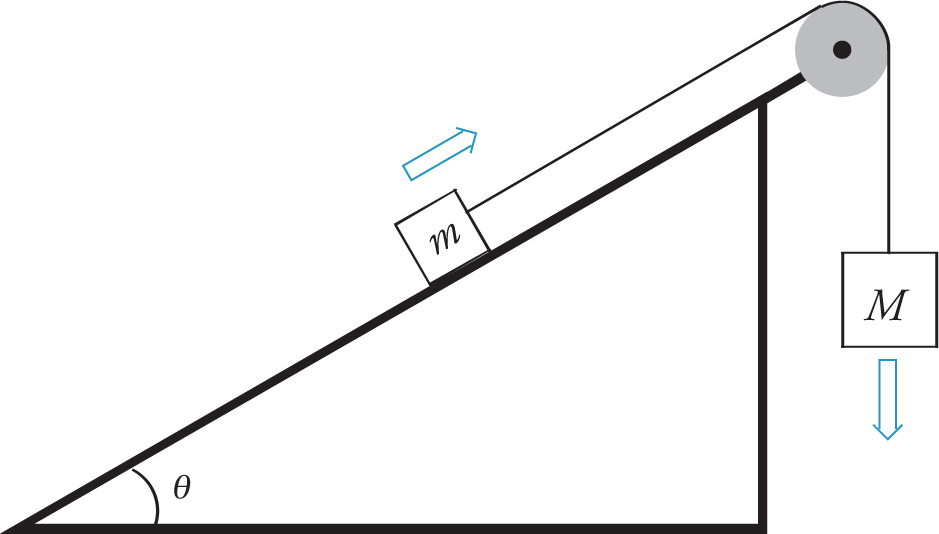

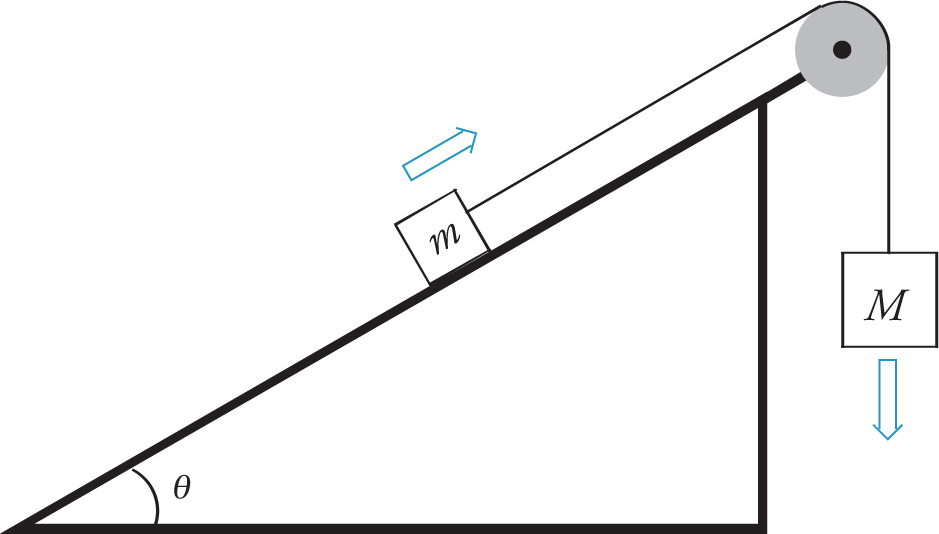

Example 4-25: In the figure below, the block of mass m slides up a frictionless inclined plane, pulled by another block of mass M that is falling. If θ = 30°, m = 20 kg, and M = 40 kg, what’s the acceleration of the block on the ramp?

Solution: On the left below are the force diagrams for the blocks. Notice that we call up the ramp the positive direction for m (because that’s where it’s going), and we call down the positive direction for M (because that’s where it’s going); these decisions are compatible, because when m moves in its positive direction, so does M.

Because up the ramp is the positive direction for little m, the force FT on m is positive and the force due to gravity along the ramp, mg sin θ, is negative; therefore, for little m, we have Fnet = FT + (–mg sin θ) = FT – mg sin θ. Since down is the positive direction for big M, the force Mg on M is positive and the force FT is negative; therefore, for big M, we have Fnet = Mg + (–FT) = Mg – FT. On the right above, we’ve written down Fnet = mass × acceleration for each block. As in the preceding example, there are two equations, (and two unknowns, FT and a). Again using the trick of adding the equations, the FT’s drop out, and all we’re left with is one unknown, a, to solve for. The calculation shown above gives a = g/2, so we get a = 5 m/s2.

NEWTON’S LAWS:

First law: Fnet = 0 ⇔ v = constant

Second law: Fnet = ma

Third law: F1-on-2 = F2-on-1

Weight: w = mg

Gravitational force: Fgrav = G

![]() given that w = Fgrav, we get g = G

given that w = Fgrav, we get g = G

![]() .

.

Kinetic friction: Ff = µkFN

Static friction: Ff,max = µsFN

µs > µk

Direction of friction is opposite to the direction of motion (or intended direction of motion).

Force due to gravity acting parallel to inclined plane: mg sin θ

Force due to gravity acting perpendicular to inclined plane: mg cos θ, where θ is measured between the incline and horizontal.

1. The gravitational force the Sun exerts on Earth is F. Mars is 1.5 times further from the Sun than Earth and its mass is

![]() of Earth’s mass. What is the gravitational force that the Sun exerts on Mars?

of Earth’s mass. What is the gravitational force that the Sun exerts on Mars?

A)

![]() F

F

B)

![]() F

F

C) 9 F

D)

![]() F

F

2. You have four frictionless, massless pulleys, arranged as shown below. If you have enough force to lift a 40 kg object without any pulleys, what is the maximum mass of the couch that can be raised with the pulley system?

A) 80 kg

B) 120 kg

C) 160 kg

D) 240 kg

3. When an object falls from a very large height, it accelerates towards Earth because of the force of gravity. Air resistance also acts on the object as it falls, and the air resistance increases as the speed of the object increases. Eventually, the force due to air resistance equals that of gravity and the object reaches terminal velocity. What best describes this situation?

A) The acceleration of the object at terminal velocity is the largest it will ever be.

B) The speed of the object increases until it hits the ground.

C) The speed of the object at terminal velocity is zero.

D) The acceleration of the object at terminal velocity is zero.

4. A box of mass m is sitting on an incline of 45° and it requires an applied force F up the incline to get the box to begin to move. What is the maximum coefficient of static friction?

A)

−1

−1

B)

C)

+1

+1

D)

![]() −1

−1

5. A 100 g block is sitting at rest on a horizontal table. According to Newton’s third law, which of the following indicates the correct action-reaction pair of the two forces?

A) The gravitational force exerted by the table on the block and the normal force exerted by the block on the table

B) The gravitational force exerted by the block on Earth and the normal force exerted by the table on the block

C) The weight of the block and the normal force exerted by the table on the block

D) The weight of the block and the gravitational force exerted by the block on Earth

6. A person is pulling a block of mass m with a force equal to its weight directed 30° above the horizontal plane across a rough surface, generating a friction f on the block. If the person is now pushing downward on the block with the same force 30° above the horizontal plane across the same rough surface, what is the friction on the block? (muk is the coefficient of kinetic friction across the surface.)

A) f

B) 1.5f

C) 2f

D) 3f

7. A 2 kg ball is rolling east (without slipping) down a hill that makes an angle of 30° with the horizontal. A child kicks the ball north with a force of 10 N. What is the net acceleration of the kicked ball?

A)

![]() /2 m/s2

/2 m/s2

B)

![]() m/s2

m/s2

C)

![]() m/s2

m/s2

D)

![]() m/s2

m/s2

When an object is falling through air, it experiences a drag force due to the frictional effects of the air. The drag force is always directed opposite the direction of motion of the object. For a spherical object, the drag force can be calculated using Stokes’ law:

FD = 6πηrν

Equation 1

where FD is the drag force, η is the coefficient of viscosity of the air, r is the radius of the sphere, and ν is the velocity of the sphere.

Since the drag force is related to the velocity of the sphere, as the sphere’s velocity increases, so does the drag force. After a certain time, the drag force will be large enough that the net force acting on the sphere is zero. At this point, the sphere falls with a constant velocity, known as the terminal velocity, νT.

A student experiments with different spherical objects falling on Earth in order to test Stokes’ law. The experiment involves dropping a variety of spheres from the balcony of a building. The relative mass and radius for each sphere are listed in Table 1.

| Object | Mass | Radius |

| Beach ball | m | 20r |

| Bowling ball | 20m | 10r |

| Golf ball | m | r |

| Ping pong ball | 0.25m | r |

Table 1 Mass and radius of spheres

1. Ignoring air resistance, which ball will hit the ground first?

A) The beach ball, since it has the largest radius.

B) The bowling ball, since it has the largest mass.

C) The golf ball, since it has the smallest radius and more mass than the ping pong ball.

D) All the balls will hit at the same time.

2. Considering air resistance, which ball will take the longest time to reach the ground when dropped, assuming none of the balls reaches its terminal velocity?

A) Beach ball

B) Bowling ball

C) Golf ball

D) Ping pong ball

3. For the experiment conducted, let v1 be the velocity of the golf ball after 10 seconds when dropped from height, h. Let v2 be the velocity of the ping pong ball after 10 seconds when dropped from the same height, h. How do v1 and v2 compare?

A) v1 < v2

B) v1 = v2

C) v1 > v2

D) It cannot be determined without information on the drag force.

4. How does the drag force on the beach ball compare to the drag force on the bowling ball when the velocities of the two balls are the same?

A) The drag force on the beach ball is 20 times the drag force on the bowling ball.

B) The drag force on the beach ball is 2 times the drag force on the bowling ball.

C) The drag force on the beach ball is

![]() the drag force on the bowling ball.

the drag force on the bowling ball.

D) The drag force on the beach ball is

![]() the drag force on the bowling ball.

the drag force on the bowling ball.

5. Which of the following gives an equation for the terminal velocity for the balls?

A) vT = mg − 6πηr

B) vT = mg + 6πηr

C) vT =

![]()

D) vT =

![]()

6. Which ball has the greatest terminal velocity?

A) Beach ball

B) Bowling ball

C) Golf ball

D) Ping pong ball

7. Which of the following changes would result in the greatest time difference between the time the first ball hits the ground and the time the last ball hits the ground?

I. Increasing the coefficient of viscosity, thus increasing the drag force.

II. Increasing the radius by a factor of 2, thus increasing the drag force.

III. Increasing the height from which the balls are dropped so that each ball reaches its terminal velocity before hitting the ground.

A) I and II

B) II and III

C) III only

D) None of the options will result in a time difference.

1. A Given that the gravitational force of the Sun on the Earth is F = GMm/r2, the force exerted on Mars is:

2. C With four pulleys you have four times the tension force acting upwards, allowing you to lift four times the weight. Since the maximum tension force is (40 kg)(10 m/s2) = 400 N, the maximum force that can be applied to the couch is 4 × 400 N = 1600 N. This corresponds to a mass of 160 kg.

3. D The net force on the object is the difference between the force due to gravity and the force due to air resistance. Therefore, as the force due to air resistance grows larger, the net force decreases, as does the acceleration, eliminating choice A. When the force due to air resistance equals that of gravity, the net force is zero, as is the acceleration (according to Newton’s second law), which makes choice D correct. When there is zero acceleration, velocity is constant, eliminating choice B and the object does not stop moving once it reaches terminal velocity, eliminating choice C.

4. A The force of static friction and the force of gravity are acting down the incline in this situation. When the box just begins to move upwards the forces in both directions are equal and the force of static friction is at its maximum. Therefore, you have the equation F = µs mg cos(45°) + mg sin(45°). Solving for µs we find the correct answer to be choice A.

5. D Since the answers could be confusing, a good strategy would be to identify all the correct action–reaction pairs, and match them to the answer choices. Here are the correct action–reaction pairs in question:

a. The weight of the block and the gravitational force exerted by the block on Earth

b. The normal force exerted by the block on the table and the normal force exerted by the table on the block

c. The gravitational force exerted by the table on the block and the gravitational force exerted by the block on the table

Of all the answer choices, only choice D matches the pairs described above.

6. D The friction f on the block is represented by the formula f = µkN, where N is the normal force acting on the block. When the force is applied 30° above the horizontal, N = mg – mg sin 30°. Since sin 30° is 0.5, N = mg – 0.5mg = 0.5mg. Substituting N into the formula for friction, it becomes f1 = 0.5µkmg. When the force is applied 30° below the horizontal, N = mg + mg sin 30° = mg + 0.5mg = 1.5mg. Substituting N into the formula for friction, it becomes f2 = 1.5µkmg = 3f1.

Therefore, the correct answer is choice D.

7. B The force of gravity that is parallel to the surface of the hill FG-parallel is the initial force acting on the ball (there is no kinetic friction force acting on the ball since the ball is rolling without slipping). Since the FG acts on the center of mass of the ball, then this force will only contribute to the ball’s translational acceleration (the torque from this force is zero, so the rotational acceleration from this force is zero), and the fact that the ball is rolling does not need to be considered in this problem. The FG that is parallel to the surface of the hill can be calculated using mg sin θ = (2 kg)(10 m/s2)sin 30° = 20(

![]() ) = 10 N. This 10 N force is acting in the east direction. The child kicks the ball with a 10 N force in the north direction. These two forces are vectors and can be added tip-to-tail to find the resulting force vector. The three force vectors make an isosceles right triangle, so the hypotenuse must be equal to a leg of the triangle multiplied by

) = 10 N. This 10 N force is acting in the east direction. The child kicks the ball with a 10 N force in the north direction. These two forces are vectors and can be added tip-to-tail to find the resulting force vector. The three force vectors make an isosceles right triangle, so the hypotenuse must be equal to a leg of the triangle multiplied by

![]() , or in this case, 10

, or in this case, 10

![]() N. (Another way to find the hypotenuse, c, is to use the Pythagorean theorem so c2 = 102 + 102 = 200 and c = 10

N. (Another way to find the hypotenuse, c, is to use the Pythagorean theorem so c2 = 102 + 102 = 200 and c = 10

![]() .)

.)

The question is asking for the acceleration of the ball, and a = F/m = (10

![]() N)/(2 kg) = 5

N)/(2 kg) = 5

![]() m/s2. The correct answer is choice B.

m/s2. The correct answer is choice B.

1. D For ideal conditions with no friction, the drag force will not exist (it is a frictional force). The acceleration of each ball can be calculated from Fnet = ma. The only force acting on the ball is its weight, so mg = ma and a = g so the acceleration on each ball will be the acceleration from gravity, g. Since all balls are dropped from the same height and have the same acceleration, they will hit the ground at the same time.

2. A The acceleration of each ball can be calculated from Fnet = ma. Since the net displacement of the balls is down, FG is in the positive direction and FG − FD = ma so mg − 6πηrv = ma and a = g − 6πηrv/m. The only values in the equation that change for the different balls are the mass and radius. The larger the ratio of r/m, the larger amount that is subtracted from g, and the slower the ball’s acceleration. The question asks for the longest time, which is the slowest acceleration. The beach ball has the largest radius/mass ratio (20r/m) and so the slowest acceleration and the longest time.

3. C The acceleration of each ball can be calculated from Fnet = ma. Since the net displacement of the balls is down, FG is in the positive direction and FG − FD = ma so mg – 6πηrv = ma and a = g − 6πηrv/m. The only value in the equation that changes for the different balls is the mass. The larger the mass, the smaller the amount that is subtracted from g, and the larger the ball’s acceleration, so the larger the ball’s velocity. Since the golf ball has the larger mass, it will have the larger velocity, v1.

4. B Using Equation 1, the drag force on the beach ball is FD, beach ball = 6πη(20r)v. The drag force on the bowling ball is FD, bowling ball = 6πη(10r)v. Thus, the drag force on the beach ball is twice the drag force on the bowling ball.

5. C The passage states that terminal velocity is reached when the net force on the sphere is zero, so Fnet = 0. The only two forces acting on the sphere are the force of gravity and the drag force, so these forces must be equal when the terminal velocity is reached. Starting with the equation FG = FD and plugging in Equation 1 yields mg = 6πηrv. Solving this equation for the velocity, which in this case is the terminal velocity, yields v = (mg)/(6πηr). Notice the equations in choices A and B include the sum and difference with the weight of the ball, which is not a velocity, so these two choices can be eliminated, leaving choice C as the correct answer.

6. B The passage states that terminal velocity is reached when the net force on the sphere is zero, so Fnet = 0. The only two forces acting on the sphere are the force of gravity and the drag force, so these forces must be equal when the terminal velocity is reached. Starting with the equation FG = FD and plugging in Equation 1 yields mg = 6πηrv. Solving this equation for the velocity, which in this case is the terminal velocity, yields v = (mg)/(6πηr). The sphere with the largest terminal velocity will have the largest ratio of mass/radius. The bowling ball has the largest mass/radius ratio (2m/r) and so will have the largest terminal velocity.

7. C To achieve the largest time difference, each ball needs to achieve the greatest difference in acceleration, which means each should achieve its maximum drag force. Since drag force depends on velocity and velocity increases until it reaches terminal velocity, then the drag force is maximized when the velocity reaches the terminal velocity. Each object needs to reach its terminal velocity, so each object needs a long enough fall to achieve terminal velocity (Item III is true and choices A and D can be eliminated). Note that neither of the remaining choices includes Item I, so Item I must be false: increasing the coefficient of viscosity will increase the drag force, but it will do so for all the balls, and not significantly impact the difference in time between the balls. Regarding Item II, increasing the radius by a factor of 2 will also increase the drag force, but it will also do so for all the balls, and not significantly impact the difference in time between the balls. Item II is false, eliminating choice B and leaving choice C as the correct answer.

1 Occasionally the MCAT may refer to rolling resistance. Rolling resistance is not technically friction; it is the force that resists an object’s rolling motion. Do not confuse rolling resistance with kinetic friction; an object can roll without sliding (or skidding), and any friction at the contact point between the object and the surface will then be static, not kinetic.