Samuel Kleinschmidt was a most remarkable man. He lived at a time and place which ideally suited him to carry on the earlier Greenlandic language work of Poul Egede and Otto Fabricius. Moreover, he was a writer, printer, cartographer, scientist, sociologist and missionary, as well as being a linguistic genius.

So wrote Kenn Harper (2010) in his biography of Kleinschmidt in Nunatsiaq Online. All of this is true, and the last description, if anything, is an understatement. Here I would like to demonstrate the incredible insight and originality of Kleischmidt’s pioneering linguistic work on the Inuit language by taking just one, admittedly rather central, example of his analyses of Inuit morphosyntax. I will scrutinize in great detail his ideas about the basic structure of West Greenlandic clauses and noun phrases and show that these ideas prefigure in one way or another every modern treatment of Inuit languages and presage notions that have only very recently been recognized in general linguistics. As far as I am concerned, the several existing attempts to “improve” upon Kleinschmidt’s system are uniformly steps backward from the incisive and elegant view of the grammatical structure of the language of the Kalaallit, the people of West Greenland. The language is Kalaallit oqaasii, “the Greenlanders language,” and they say they speak Kalaallisut, “like a Greenlander.” In this paper I refer to the language using the traditional term West Greenlandic, or just Greenlandic, to save space.

Before delving into the theory of Greenlandic that Samuel Kleinschmidt worked out 160 years ago, I provide a very brief biography of this great man based on the much more detailed biographies by Rosing (1949) and Rosing and Preston (1951).

Samuel Petrus Kleinschmidt (Sâmuale to the Greenlanders) was born on February 27, 1814, in the small Moravian missionary village of Alluitsoq/Lichtenau in South Greenland to a Danish mother and a German father. Thus, as conjectured by Rosing (1949) and Rosing and Preston (1951), he must have grown up being trilingual, knowing the local dialect of Greenlandic, as well as Danish and German as mother tongues. As they surmise, this undoubtedly sharpened his natural linguistic acumen. At the age of nine he was sent to Europe for an education, spending time first in Saxony, then in Holland, and finally in Denmark, before returning to Greenland in 1840. During his time in Europe, Kleinschmidt picked up Greek, Latin, French, English, and Dutch, bringing to eight the number of languages he knew by the age of 26 (Rosing, 1949; Rosing and Preston, 1951). His picture (Figure 3.1) toward the end of his life is the only known photograph of him, taken in 1885 by J. A. D. Jensen.

Figure 3.1 Samuel Kleinschmidt, 1814–1886, the originator of Greenlandic Inuit grammar. This is the only known picture of Kleinschmidt (possibly taken around 1884–1885). Original photograph by J. A. D. Jensen. Photograph courtesy of Lisbeth Valgreen, Danish Arctic Institute.

Within six years of his return to Alluitsoq/Lichtenau, Kleinschmidt completed the manuscript of his extraordinary German-language grammar of West Greenlandic, although it would be five more years before it was published as Grammatik der grönländischen Sprache (Kleinschmidt, 1851). Twenty years later, his second grand linguistic oeuvre appeared, his 1871 Greenlandic to Danish dictionary, Den Grønlandske Ordbog. By this time he had moved to the Moravian mission at Neu Herrenhut, in modern-day Nuuk. From there he defected to the Danish Lutheran mission, where he was allowed to devote more time to the people of Greenland and their language. He passed away in 1886 in Neu Herrenhut (Nuuk), having spent 54 years of his long life teaching, preaching, writing, and doing linguistic research in Greenland. It is to Kleinschmidt’s first masterwork, his stunning grammar of the Greenlandic language, that I will devote my attention.

My purpose here is to explain in as nontechnical a manner as possible the grammatical truths that Samuel Kleinschmidt discovered. My hope is that people interested in the history of Yupik-Inuit-Aleut linguistic studies, regardless of their areas of expertise, will be able to understand the giant strides in grammatical thinking that this humble missionary was able to make. I will not make any new points or teach any new lessons to sophisticated grammaticians, but instead, I will try to make Kleinschmidt’s accomplishments clear to whoever reads this.

This paper is by no means the first, nor by any means the most thorough, treatise on Samuel Kleinschmidt’s linguistic work and impact. The reader’s attention is particularly directed to the much deeper and more scholarly works by Elke Nowak (1987a, 1987b, 1998). Anthony Woodbury’s master’s essay of 1975 is the earliest example I know of that clearly explains how Greenlandic grammar includes both ergative and accusative processes of the sort to be discussed below.

In the middle of the nineteenth century ordinary grammatical description of languages was based upon meaning, using the categories of Latin grammar. All of Kleinschmidt’s predecessors employed that style of analysis. Kleinschmidt himself discounts an unpublished earlier Greenlandic grammar by Christopher Königseer (1723–1786) produced around 1780 (Pilling, 1887:54; Nowak, 1992:162) as “based entirely upon European (or Latin) model.” Kleinschmidt complemented Otto Fabricius (1791, 1801), another pioneer in studies of Greenlandic language, as having freed himself in many respects from the Latin model, the model that was generally accepted as the universal pattern for language.1 But, as I will briefly show, Fabricius hewed much more closely to the Latin model than Kleinschmidt did in his incredibly original view of things.

Kleinschmidt’s description of Inuit grammar is still accepted today in all its fundamental respects. Just as Newton’s laws of motion continue to hold for macroscopic bodies, Kleinschmidt’s laws of Greenlandic grammar continue to hold at the macrodescriptive level. The laws of classical mechanics are now seen as special cases of deeper truths of quantum theory and relativity. Similarly, a great deal of speculation based on modern theoretical constructs and data from a variety of languages has been expended in an effort to account for, rather than simply assume, the rules that Kleinschmidt revealed for Inuit languages. So far, however, no consensus has been achieved.2

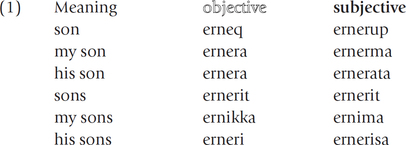

Greenlandic nouns have two synonymous forms whose occurrence is determined by their role in sentences, which Kleinschmidt called the subjective form and the objective form. The noun meaning “son,” for example, is ernerup in the subjective form and erneq in the objective form. Nouns can also indicate their possessors, and those more complex inflections also occur in both the subjective and the objective, as shown in the following very partial paradigm. For graphic contrast I will write objective in an outline font and subjective in bold.

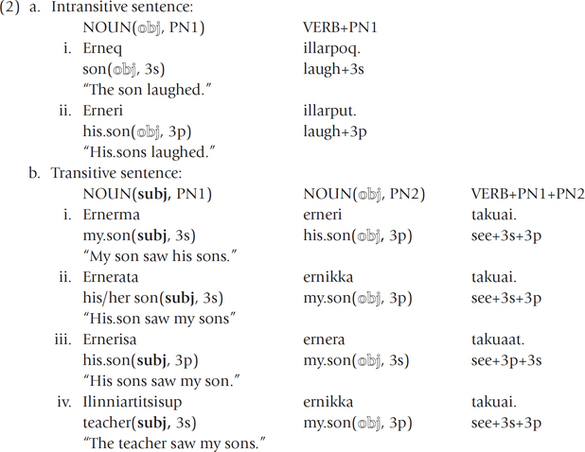

Within sentences, these two forms are distributed as follows, where PN1 is a person and number inflection that agrees with the objective form and PN2 is in agreement with the person and number of the subjective noun. Intransitive sentences include only an objective noun, whereas transitive clauses have both an objective noun and a subjective noun. These properties are illustrated with the examples below templates (2a) and (2b).3

To complete the picture, it needs to be noted that the subjective form of a noun is also used as the possessor of another noun, as in (3), where the possessor’s person and number are reflected on the possessed noun, which also shows its own number.

Finally, note that transitive sentences like (3) can be turned into intransitive sentences in two different ways: (4a) is a passive sentence in which what corresponds to the subjective noun in the transitive is realized as an oblique-case noun called the ablative; (4b) is a sentence in which what would have been the objective-case noun appears in an oblique case called the instrumental. Nowadays the latter kind of sentence is usually called an antipassive, but I will label it semitransitive following Kleinschmidt’s German term halbtransitiv. In both the passive and the semitransitive the noun that remains after either the subjective or the objective is demoted to oblique status and appears in the objective since it is the main noun of an intransitive sentence:

The earliest published grammars of Greenlandic—the first of any Eskimo/Inuit language—by Poul Egede (1760) and Otto Fabricius (1791, 1801) analyzed the language to a greater or lesser extent on the model of Latin grammars. That grammatical treatment was largely based on meaning, treating the various categories as expressing one or more meanings and various meanings as being represented by one or more forms. Their treatment of Greenlandic in these early works does that but also assumes the same set of cases of nouns as Latin has. To see this, take a close look at part of a chart that Fabricius (1801:79) presents that shows how the various forms of Greenlandic can be shoehorned into the case system of Latin.4 The chart presents various forms of the noun nuna (“land”) in the right-hand column, and the left-hand column presents exactly the Latin cases in the traditional order in which they appear in Latin grammars.5

Notice that Fabricius’s system assigns two forms to three of these Latin-like cases. Furthermore, the form núna instantiates three different cases, and núnab is one of the forms of two different cases. It is clear that something is deeply wrong with Egede’s and Fabricius’s conceptions of the structure of Kalaallisut. Despite the clumsy description, the language is not factually misrepresented. Fabricius’s grammar was a notable achievement, and its failings could be blamed on the flawed idea that languages could all be comfortable in the grammatical bed constructed in Rome a long time ago. All the more remarkable, then, that another European, Samuel Kleinschmidt, schooled in the same grammatical tradition as Egede and Fabricius, was able to completely abandon the ideas that led other early grammarians so far astray and come up with a brand-new, much superior scheme based on the actual categories found in this non-European language.

Kleinschmidt’s analysis of basic Greenlandic morphosyntax is contained in two brief passages in his grammar:

(6) All nouns and all the suffixes that appear on nouns—the latter in the singular, dual, and plural, the nouns themselves, however only in the singular, have two otherwise synonymous forms: subjective and objective, whose use is correlated with the use of suffixes. That is to say, when two entities are connected by a suffix as subject and object, either as agent and patient or possessor and possessed, then the word that designates the subject—the agent or possessor—has the subjective form and the one that designates the object—the patient or the possessed—[has] the objective form.6 (Kleinschmidt, 1851:14)

(7) Since one usually understands under the designation “subject” in general that entity that is talked about in the sentence—[in answer] to the question: who? [wer]—regardless of whether it has an object or not, here it must be observed once and for all that in Greenlandic a subject without an object is unthinkable. For that reason … everywhere in what follows the word “project” is used when what is meant is the entity that is spoken of in general (standing [in answer] to the question: who? [wer]) without consideration of whether any object is intended. It follows from this, among other things, that the project of such verbs that do not have a suffix have the objective form.7 (Kleinschmidt, 1851:15)

One term that plays a prominent role in both passages is suffix. What Kleinschmidt meant by that term is something very specific to the analysis of Greenlandic and in this sense its usage goes all the way back to Egede (1760). A suffix, in this context, refers to the extra set of person and number features that is found with transitive verbs and possessed nouns. For example, the inflection in illarpoq, “he/she laughs,” and in erneq, “son” (example 2a.i), indicates only one set of person and number features—third-person singular in both cases, referring to the entity doing the laughing in the case of the verb and referring to the son in the case of the noun. These forms do not have a suffix. In example 2b.iv both the verb takuai, “he sees them,” and the noun ernikka, “my sons,” indicate reference to two entities. In the verb the one doing the seeing is third-person singular, and the ones seen are third-person plural. In the noun, the “possessor” (the speaker) is first-person singular and the “possessed” (the speaker’s sons) is third-person plural.

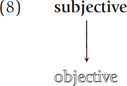

Taken as wholes, I think that (6) and (7) are not particularly transparent, even to experts in grammar. What I propose to do, then, is to take the two passages apart and explain piece by piece the implications of Kleinschmidt’s pronouncements. Let’s begin with the important observation in (7) “that in Greenlandic a subject without an object is unthinkable.” Since according to (6) the subject is in the subjective form and the object in the objective form, we can represent this idea graphically as (8):

Now we also know from (6) that the use of subjective and objective “is correlated with the use of suffixes.” That is to say, where there is a subjective (and therefore, according to (8), also an objective), there is a suffix on the transitive verb or the possessed noun:

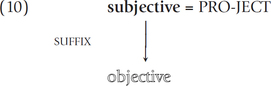

Kleinschmidt defines a second term of art in (7), the project. (I will present the word in this usage in an uppercase font with a hyphen, as PRO-JECT, in order to distinguish it from the ordinary English word project.) According to Kleinschmidt, a PRO-JECT is “the entity that is spoken of in general (standing [in answer] to the question: who? [wer]) without consideration of whether any object is intended.” In Greenlandic, the answer to a transitive question corresponding to a German wer question such as “Wer hat die Kinder geküßt?” (“Who kissed the children?”) would have a subjective nominal in place of wer, as in (4a), Ataatap meeqqat kunippai, “Father kissed the children.” Kleinschmidt’s complete description of transitive sentences—those with a subject, an object, and a suffix—can therefore be represented as (10).

To complete that picture, we need to see what Kleinschmidt says about intransitive sentences, those whose verbs lack a suffix. Without a suffix, there can be no subject and hence no subjective form. But something is talked about in intransitive sentences too, so they must also have a PRO-JECT. Samuel Kleinschmidt summed it up this way: “It follows from this, among other things, that the project of such verbs that do not have a suffix have the objective form.” There can be no subjective without an objective, but there can be an objective without a subjective. The sole entity with which the verb agrees in an intransitive is its PRO-JECT, and it therefore must appear in the objective form! (This little theorem is one of the neatest pieces of grammatical logic I know of, a far tighter argument than most modern examples, whose reasoning depends on a vastly greater number of interlocking and often questionable assumptions.)

The complete picture of basic Greenlandic grammar that Samuel Kleinschmidt gave us is, then, (11):

Kleinschmidt’s idea provides two distinct groupings of the nominal elements of transitive and intransitive clauses depending on whether the sole nominal element of the intransitive clause is treated in the same way as the subjective element of the transitive clause or whether it is treated in the same way as the objective element of the transitive clause. His groundbreaking insight is that both of these alignments operate simultaneously in the grammatical organization of Greenlandic and related Inuit languages.

First, there is the idea that the PRO-JECT identifies the subjective of the transitive sentence with the only nominal in the intransitive, an objective form, as Kleinschmidt argued it must be. Both are PRO-JECTS. The objective of the transitive sentence, on the other hand, is not a PRO-JECT. This identification is represented in (12a).

At the same time, the single nominal in an intransitive clause is identified with the objective of the transitive clause since both are in the objective case, whereas the subjective of the transitive clause is not objective, which we see in (12b).

The association illustrated in (12a) is called a nominative-accusative pattern after the way the nominative and accusative cases of Latin, German, and many other languages of Europe are distributed. The pattern in (12b), although quite commonly expressed in languages of the world other than Greenlandic, is much less familiar to nonlinguists. It is usually called an ergative-absolutive pattern, where the ergative case is merely a different name for Samuel Kleinschmidt’s subjective form, and the absolutive case is the same thing as his objective form.

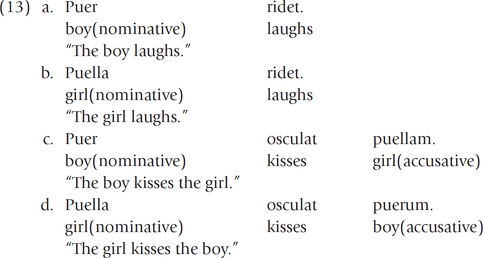

The more familiar nominative-accusative alignment can be illustrated with examples from Latin, although many other European languages could have been used as well.8

In (13) we see two similar intransitive sentences and two similar transitive sentences.

The nominative forms of the nouns puer and puella are used for the only nominal of the intransitives (13a) and (13b) and the agent of the transitive sentences (13c) and (13d). The accusative forms, puerum and puellam, are reserved for objects of transitive sentences. In other words, the Latin nominative is applied to “the entity that is spoken of,” that is, the PRO-JECT of a sentence.

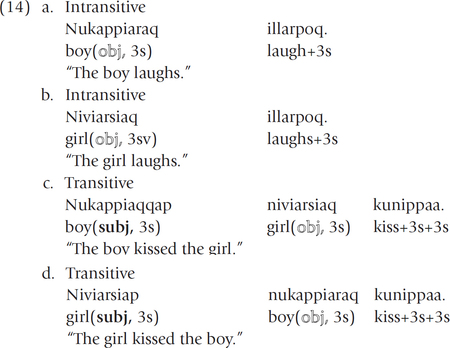

The examples in (14) are semantically parallel to the Latin examples above:

Instead of the nominative-accusative correspondence between the forms of the one nominal in an intransitive clause and one of the two nominals in a transitive clause that we found in Latin, in Greenlandic we have an ergative-absolutive correspondence: both the transitive and intransitive clauses include an objective case nominal, but that nominal is the notional object of the transitive, and there is a special form, the subjective, that marks the kisser, the agent in the transitive event. Writing more than a 160 years ago, Kleinschmidt recognized ergative-absolutive patterning just as clearly, and in much the same way, as do linguists today. Credit for this discovery is usually given to Hugo Schuchardt (1895), but Kleinschmidt got there first: Samuel Petrus Kleinschmidt was the discoverer of ergativity. Furthermore, as I am about to show, Kleinschmidt’s view of ergativity was better than Schuchardt’s.

The nominative-accusative grammatical regime seemed entirely natural to most nineteenth-century scholars, so much so that the grammarians who preceded Kleinschmidt in Greenland used the Latin paradigm of cases of the noun to describe Greenlandic, as we have seen. Hugo Schuchardt, writing more than 40 years after Kleinschmidt, did not understand the ergative-absolutive pattern on its own terms as an alternative formal identification among parts of transitive and intransitive sentences on par with but different from the nominative-accusative identification that we find in Latin, German, and so on. Rather, Schuchardt saw the ergative-absolutive system as a distortion of the nominative-accusative system. Specifically, he claimed that in ergatively oriented grammars, the transitive has a “passive character” and argued for it by pointing out that if you take a language like Latin, or, for that matter, English, and recast all of its transitive sentences as passives, you get what looks like an ergative-absolutive alignment. In (15a) and (15b) the agent of the transitive appears as he and she, the same form that the only nominal of intransitive sentences take in (15c) and (15d). He and she are accordingly nominatives.

(15) a. He kissed her.

b. She kissed him.

c. He laughed.

d. She laughed.

However, if we replace the transitive sentences in (15) with passive sentences, the notional object of the transitive actions—the person that is kissed—appears as he and she with the same form as the subject of the intransitive sentences, making them absolutives. A contrasting form (by him, by her) is distributed in an ergative fashion, marking only the semantic agent of a transitive clause.

(16) a. He kissed her. She was kissed by him.

b. She kissed him. He was kissed by her.

c. He laughed.

d. She laughed.

But these are intransitive passive sentences in which the agent is backgrounded. They are quite unlike the active, transitive sentences of Greenlandic. I surmise that if Schuchardt had been a speaker of an ergative language, like Samuel Kleinschmidt was, he might not have entertained the idea that transitive sentences in a language like Greenlandic are somehow passive. There is, in fact, a passive sentence in Greenlandic—Nukappiaraq niviarsiamit kuninneqarpoq, “The boy was kissed by the girl”—in which the agent is demoted in something like the same way it is in the English passive. If Schuchardt were right about the “passive character” of the transitive sentences of ergatively marked sentences in Greenlandic, then there should not be an actual passive in the language. Kleinschmidt did not discover the “passive character of the transitive” in certain languages; he discovered the phenomenon of ergativity.

Kleinschmidt’s observations concerning the form of nominals place the object of transitives and the subject of intransitives in the formal category objective, producing an ergative-absolutive alignment. At the same time, Kleinschmidt aligned the subjective of the transitive and the only required nominal of the intransitive—the objective—through his recognition of the category PRO-JECT, “the entity that is spoken of … standing [in answer] to the question: who? [wer].”9

Kleinschmidt’s definition of the PRO-JECT makes use of the nominative German pronoun wer. So did Greenland’s genius succumb to the same ethnocentric force that seduced Schuchardt? Did he find a way of insinuating nominativity into a deeply ergative language? Of course not! With his usual grammatical acuity, Kleinschmidt described several ways in which nominative-accusative organization characterizes certain phenomena in the grammar of Greenlandic, whereas others, as we have seen, follow the ergative-absolutive plan. Before considering a few of these, let me come to the point: Kleinschmidt recognized that a single language could simultaneously present both ergative and accusative alignments without contradiction. This is the idea of split ergativity, which did not become commonplace in linguistics until Michael Silverstein’s (1976) seminal paper “Hierarchy of Features and Ergativity” appeared some 125 years after Kleinschmidt’s Grammatik der grönländischen Sprache was published.

So let us return to Kleinschmidt’s text to see how he showed that the PRO-JECT sometimes is manifested in the form of nominal expressions in Greenlandic. Kleinschmidt had a term for such forms, namely, nominative. He accurately described a few special nominals that have nominative PRO-JECTs as agents of transitive and subjects of intransitive sentences and a contrasting form, which Kleinschmidt accurately labeled accusative, that is used for the non-agent of transitive sentences.

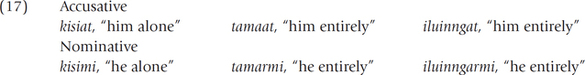

One sort of category that Kleinschmidt mentioned is composed of the stems kisi- (“only”), tamaq- (“all”), and iluinngaq- (“entire”), a group that I have labeled “exhaustives” (Sadock, 2003).10 Kleinschmidt provides a paradigm of these stems, the relevant first two lines of which are as follows:

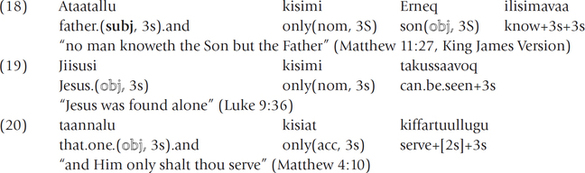

He goes on to explain (Kleinschmidt, 1851:43–44) that “for the third person the a-suffixes form an accusative, and the e-suffixes a nominative.” I will explain his distinction between a-suffixes and e-suffixes presently; for now it is sufficient know that -at is an a-suffix and -mi is an e-suffix. The following quotations from Biibili (Det Danske Bibelselskab, 1999), the Bible translated by the Danish Bible Society and published on the web, will illustrate the use of nominative kisimi and accusative kisiat.

In (18) kisimi modifies a subjective form agent of a transitive sentence, but in (19) the same word modifies an objective subject of an intransitive clause. An objective form is also modified in (20), but there it is the object of a transitive verb, and the modifier is kisiat, an accusative. Examples (18) and (19) taken together and examples (19) and (20) taken together are especially important because they prove the independence of the ergative-absolutive case system and the nominative-accusative case system. Regardless of the whether a noun is subjective (i.e., ergative) or objective, it can be modified by a nominative, as long as it is a PRO-JECT.

In several other places in his grammar, Kleinschmidt identifies very central aspects of Greenlandic syntax and semantics that are controlled exactly by the PRO-JECT, even when there is no item in the sentence that is nominative in form. The phenomena mainly regard the way certain kinds of coreference are determined, in particular, what Kleinschmidt calls the a-suffixes and e-suffixes that were mentioned in the discussion above. There are two sets of person and number inflections in the third person that, among other functions, indicate the reference of the possessor of nouns. The general principle that Kleinschmidt discovered is that a third-person e-suffix (“ES” in glosses) is a sort of reflexive category that refers to the PRO-JECT to which it is immediately subordinate. (See Sadock, 1994, for a formal account.) The simplest example to understand is the reference of the possessor of an oblique-case noun. Kleinschmidt put it this way:

(21) If a noun-word is to have a suffix [a possessor ending] and an apposition [an oblique case marker] such a word acquires an e-suffix when what it names is the possession of the project of the verb that it is subordinate to, otherwise [it gets] an a-suffix.11 (Kleinschmidt, 1851:72)

If the possessive suffix is an e-suffix, it will refer to the governing PRO-JECT, which will be the subjective element of a transitive clause or the objective element of an intransitive clause. Thus, the e-suffixes pick out what would be a nominative in a language that was aligned as Latin is. An a-suffix (“AS” in glosses) would be used to refer to anything else.

As an example, consider the locative case (in, at, on) and allative case (to, toward) of the noun nuna (“land,” “country”) with a-suffixes and e-suffixes:

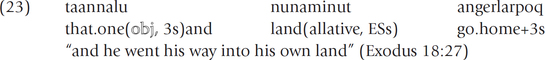

The following are additional biblical examples that illustrate Kleinschmidt’s principle. In these examples, the notations ESs and ASs indicate e-suffix singular and a-suffix singular, respectively.

The question is, whose own land? According to Kleinschmidt’s rule, it is the land of the PRO-JECT of the clause, which in this case is taanna (“that one”) since it is the objective element of an intransitive clause.

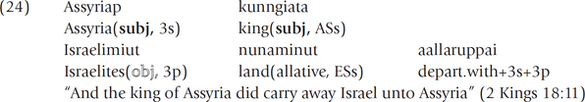

The next example is a transitive clause:

The word nunaminut means “to third person’s land.” There are two third persons it could potentially refer to, the king of Assyria or the Israelites.12 But nunaminut has an e-suffix, so it refers to the PRO-JECT of this transitive clause, which is the subjective phrase Assyriap kunngiata. Thus nunaminut refers to the Assyrian King’s land, i.e., Assyria.

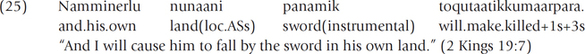

To fill out the paradigm, consider the reference of nunaani in the next example:

The I in the passage (referring to God) is the subjective PRO-JECT in the clause whose verb is toqutaatikkumaarpara, “I will cause him to be killed.” The possessor of the land is someone other than the PRO-JECT, and therefore, reference to him must be in terms of an a-suffix, which it is in nunaani.

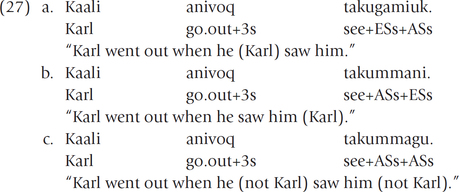

The PRO-JECT also figures in the determination of the reference of person and number inflection of subordinate moods. Example (26) shows forms of the verb taku- (“to see”) in various possible combinations of third-person participants for both intransitive—(26a) and (26b)—and transitive—(26c), (26d), and (26e)—uses. The form also indicates that the verb is in a subordinate mood that means “when in the past S” or “because S.”

In all these cases, an e-suffix refers to the PRO-JECT of the main clause. With a main clause like Kaalip naveerpaa, “Karl scolded him/her,” or Kaali anivoq, “Karl went out,” the e-suffix will refer to Karl, and the a-suffix will refer to someone other than Karl.

Samuel Petrus Kleinschmidt, then, was the discoverer of the commonplace fact of ergative alignments and nominative alignments in the same language, a phenomenon known today as split ergativity. This he did a century and a quarter before it was made a standard notion of linguistic description in Silverstein (1976).14

It is fair to say that Samuel Kleinschmidt’s effect on Inuit language studies has been profound. In one way or another, every modern study of an Inuit language demonstrates his influence. Here I would like to end by saying something about Kleinschmidt’s influence on my own research and thinking.

The year 1951 marked the centennial of the publication of Kleinschmidt’s Grammatik der grönländischen Sprache (1851). This year was commemorated in the pages of the prestigious International Journal of American Linguistics, every issue of which included one or two “Kleinschmidt Centennial” papers by noted linguists.15 Twenty years later, in 1970, nearly a hundred years after the publication of Kleinschmidt’s Den Grønlandske Ordbog (1871), a conference on Eskimo and Aleut linguistics was convened at the University of Chicago, where I was a freshman faculty member. The papers from this symposium were subsequently published (Hamp, 1976). In 1969–1970, Professor Eric P. Hamp, who hosted the conference, sponsored a young Greenlander, Carl Christian Olsen (Puju), then a graduate student at the University of Copenhagen, to come to Chicago, where he would be able to learn some up-to-date linguistic theory, for the academic year.16

Puju and I hit it off and remain great friends to this day. We worked up a short article that was later published in the conference proceedings volume (Sadock and Olsen, 1976). That conference and my friendship with Puju changed my life. That summer I spent five weeks in Sisimiut, Greenland, Puju’s hometown, and I have been back to Greenland so many times I’ve lost track. Much of my academic life has been spent working with Greenlandic consultants, thinking about and striving to speak Kalaallisut (“like a Greenlander”), a pleasant task that has rewarded me both personally and professionally. In the latter respect, I owe a great deal to Samuel Kleinschmidt, whose grammar I pored over with Puju’s help. That book awakened in me an appreciation for the beauty of Inuit grammar and a still-unfulfilled desire to be able to speak Greenlandic well.

According to Kleinschmidt, three competing forces conspire to produce the elaborate patterns that have been described here. First, there is the syntactic requirement that every sentence contains, at least implicitly, an objective case noun. Next, there is a semantic association of the subjective case with the agent of a transitive action. Finally, there is the information-structural idea that every clause contains a PROJECT, an entity that is talked about, and that it is the subjective nominal of a transitive clause and the objective of an intransitive clause.

My work on Greenlandic grammar led me to the conclude that some apparently complex features of this impressive language look much less puzzling if they are seen as arising from necessary discrepancies between simple alternative representations of linguistic expressions. I thought this idea, which was announced in Sadock (1985), was highly original, but Kleinschmidt’s theory of split ergativity contains more or less the same insight. I am sure that at least in a subliminal way, my idea of the competing nature of morphology, syntax, and semantics was directly inspired by the way Kleinschmidt described West Greenlandic.

Kleinschmidt anticipated Schuchardt by 44 years, Silverstein by 125 years, and me by 134 years. He was indeed, as Kenn Harper wrote, “a linguistic genius.”

The present paper has benefited greatly from Willem de Reuse’s meticulous review and Igor Krupnik’s editorial suggestions. Portions of this paper are based upon work supported by National Science Foundation grant number BCS105649. I am grateful to Lisbeth Valgreen and the Danish Arctic Institute for a copy of Kleinschmidt’s photograph and for the permission to reproduce it in this book.

1. Kleinschmidt (1851:v) wrote, “Von den beide spätern steht die Königseer’sche noch ganz auf europäischem resp. lateinischem standpunkt, wogegen Fabricius sich in manchen stücken in einem für seine zeit allerdings bemerkenwerthen grade von der damals noch fast unbestrittenen autorität des lateinischen als alleinigen sprachmusters frei gemacht hat.” In my translation, “Of the two later ones, Königseer’s is based entirely on a European, in particular a Latin point of view, whereas Fabricius freed himself in many ways to a degree that was genuinely remarkable for his time from what was then the unchallenged authority of Latin as the sole pattern for language.”

2. Linguistically sophisticated readers are undoubtedly familiar with the impressive literature on case marking and agreement. Those who are not might consult collections such as Boeckx (2006) and Johns et al. (2006).

3. The notation is common in the linguistic literature. There are three persons, speaker = 1, hearer = 2, and other = 3, and two numbers, singular = sg, and plural = pl. So 1s is the speaker and no one else (English I or me) and 3p is more than one person or thing, not including either the speaker or the hearer. The linguistically trained reader will immediately recognize (2a) and (2b) as an ergative pattern, where Kleischmidt’s objective is the absolutive case, and his subjective is the ergative. This concept is quite familiar to modern grammarians, but Kleinschmidt recognized it and described it accurately before anyone else.

4. Fabricius’s full chart includes duals and plurals, but it also lists a vocative case, which brings in yet another error of analysis.

5. Fabricius writes the word with an unnecessary acute accent. Among other things, Kleinschmidt reformed the spelling of Greenlandic, making it possible to pronounce any word correctly from its written form and thus eliminating the superfluous accent. Such an accent remains in Kleinschmidt’s orthography, but it has a genuine meaning: It marks a short vowel followed by a geminate consonant.

6. The translation is mine. In Kleinschmidt’s original German, “Dann haben alle nennörter, und alle an nennwörter vorkommenden suffixe - und zwar letztere in der einh., zweih. u. mehrheit, die nennwörter selbst aber nur in der einhheit—zweierlei übrigens gleichbedeutende formen: subjective und objective, deren gebrauch mit dem suffixe zusammenhängt. Nämlich wenn zwei gegenstände als subject und object, d. h. entweder als thäter und thatziel, oder als besitzer und besitz durch ein suffix mit einander verbunden sind (gleichviel ob beide genannt sind oder nicht), so hat das wort, was das subject - den thäter oder bestzer - benennt, subjective form, und das, was das object—das thatziel oder den besitz—benennt, objective form.”

7. This English version is mine. In Kleinschmidt (1851) it reads, “Da man unter der benennung “subject” gewöhnlich im allgemeinen denjenigen gegenstand versteht, von welchem—auf die frage: wer?—im satz die rede ist, gleichviel ob derselbe ein object hat oder nicht, so ist hier ein—für allemal zu bemerken, dass im gröl. ein subject ohne object undenkbar ist. Darum, und weil die benennung “subject” hiser ausserdem auch für den besitzer in anspruch genomnmen ist, so ist im folgenden überall, wo der (auf die frage: wer? stehende) gegenstand der rede im allgemeinen und ohne rücksicht auf ein etwaniges object gemeint ist, dafür die benennung “project” angewendet. Daraus, dass subjective form und suffix unzertrennlish zusammengehören, folgt unter andern, dass das project solcher redewörter, die keinen suffix haben, objective form, hat.”

8. Basque is a clear exception since it displays ergative organization in a very thorough way.

9. This is a semantico-functional, rather than a formal, notion: there are two different forms (subjective and objective) but one encoded meaning function—the entity that is talked about. Insofar as Kleinschmidt traces the apparent conflict between ergative and accusative alignments to their existence on orthogonal organizational planes, he makes use of the same technique I have advocated for 30 years in my work on autonomous modular grammar (e.g., Sadock, 2012). I am therefore strongly inclined to accept Kleinschmidt’s functional theory of the PRO-JECT, but unfortunately, I cannot decide whether Kleinschmidt is right about it. For the immediate purposes of this paper, it does not matter. The demonstration of his comprehension of a tension between ergative and accusative due to competing forces does not depend upon one of those forces being functional. Silverstein (1976) shows that competing semantic hierarchies facilitate or inhibit the ergative alignment or the accusative alignment.

10. Iluinngaq- is usually iluunngaq- in the modern language, where, in fact, it is little used.

11. In Kleinschmidt’s text, “Wenn das besitzverhältniss mit dem casus obliquus … zusammentrifft, d.h. wenn ein nennwort ein suffix und eine apposition haben soll, so richtet sich der gebrauch der a- und e-suffixe der 3ten pers. nach dem selben regel, nämlich ein e-suff. erhält ein solches wort, wenn das dadurch benannte besitz des projects desjenigenredeworts ist, dem es untergeordnet ist, sonst ein a-suffix”; the translation is mine.

12. I have told a little white lie here. The form nunaminut is not potentially ambiguous in this context because it has singular-singular agreement, “his/her own land,” so under no circumstances would it have the plural Israelimiut as an antecedent. If we substitute a singular, say israelimioq (“the Israelite”), for the plural, then the form could conceivably have it as a reference, but the substitution in (24) would not change the reference. Furthermore, if we substituted nunaminnut (“their own land”) for nunaminut, the form would be ungrammatical because the PRO-JECT is singular.

13. There is no e-suffix with the e-suffix combination in this table because such a combination would have to be a reflexive clause, both subject and object referring to the PRO-JECT of the main clause. But all reflexive clauses in Greenlandic are intransitive, so the e-suffix and e-suffix combination are excluded.

14. Woodbury (1975) reveals the remarkable fact that a single category of inflection, Kleinschmidt’s infinitive, is simultaneously ergative-absolutive and nominative-accusative in its properties. Although Kleinschmidt’s description of the infinitive implies the split nature of this construction, as Woodbury observes, Kleinschmidt did not state that observation directly in his treatment.

15. The papers from the Kleinschmidt Centennial (Bergsland, 1951; Hammerich, 1951a, 1951b; Marsh and Swadesh, 1951; Rosing and Preston, 1951; Swadesh, 1951) are included in the reference section thanks to Igor Krupnik.

16. Carl Christian Olsen has had a distinguished career and is well known throughout the North. He has done an enormous amount of important work promoting the Inuit language in and outside of Greenland. He has secured for Kalaallisut a bright future and continual development. In Greenland he has served in many important capacities having to do with language matters. He has also played prominent roles in the transnational Inuit Circumpolar Conference. I am proud to know him.

Bergsland, Knud. 1951. Kleinschmidt Centennial IV: Aleut Demonstratives and the Aleut-Eskimo Relationship. International Journal of American Linguistics, 17(3):167–179.

Boeckx, Cedric, ed. 2006. Agreement Systems. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Det Danske Bibelselskab. 1999. Biibili. Online Bible produced by TEXTware A-S. http://old.bibelselskabet.dk/grobib/web/bibelen.htm (accessed July 31, 2015).

Egede, Poul. 1760. Grammatica Grönlandica. Copenhagen: Gottmann Kisel.

Fabricius, Otto. 1791. Forsøg til en forbedret grønlandsk grammatica. Copenhagen: C. F. Schubart.

———. 1801. Forsøg til en forbedret grønlandsk grammatica: Andet Oplag [2nd ed.]. Copenhagen: C. F. Schubart.

Hammerich, Louis L. 1951a. Kleinschmidt Centennial I: The Case of Eskimo. International Journal of American Linguistics, 17(1):18–22.

Hammerich, Louis L. 1951b. Kleinschmidt Centennial VI: Can Eskimo Be Related to Indo-European? International Journal of American Linguistics, 17(4): 217–223.

Hamp, Eric P., ed. 1976. Papers on Eskimo and Aleut Linguistics. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Harper, Kenn. 2010. “Samuel Kleinschmidt, Greenlandic Language Pioneer.” Taissumani: Around the Arctic. Nunatsiaq Online, February 26. http://www.nunatsiaqonline.ca/stories/article/taissumani_feb._26 (accessed July 29, 2015).

Johns, Alana, Diane Massam, and Juvenal Ndayiragije, eds. 2006. Ergativity: Emerging Issues. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, Vol. 65. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Kleinschmidt, Samuel. 1851. Grammatik der grönländischen Sprache: mit teilweisem Einschluß des Labradordialekts. Berlin: G. Reimer. [Photographic reprint, Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1968.]

———. 1871. Den Groenlandske Ordbog. Copenhagen: Louis Kleins Bogtrykkeri.

Marsh, Gordon, and Morris Swadesh. 1951. Kleinschmidt Centennial V: Eskimo-Aleut Correspondences. International Journal of American Linguistics, 17(4):209–216.

Nowak, Elke. 1987a. Samuel Kleinschmidt’s “Grammatik der grönländischen Sprache.” Hildesheim, Germany: Olms.

———. 1987b. “Towards a Greenlandic Point of View: A Re-discovery of Kleinschmidt’s Grammatik der grönländischen Sprache.” In The Nordic Languages and Modern Linguistics 6, pp. 289–299. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press.

———. 1992. “How to ‘Improve’ a Language: The Case of Eighteenth Century Description of Greenlandic.” In Diversions of Galway, ed. A. Ahlqvist, pp. 157–168. Studies in the History of the Language Sciences 68. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

———. 1998. “Samuel Kleinschmidt.” In Biographical Dictionary of Western Linguistics, ed. J. Joseph and P. Swiggers. London: Routledge.

Pilling, James C. 1887. Bibliography of the Eskimo Languages. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 1. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

Rosing, Otto. 1949. Samuel Petrus Kleinschmidt: inûneranik univkâK. Nuuk, Greenland: Kujatâne landskassip naKitertitai. Rosing, Otto, and W. D. Preston. 1951. Kleinschmidt Centennial II: Samuel Petrus Kleinschmidt. International Journal of American Linguistics, 17(2):63–65.

Sadock, Jerrold M. 1985. Autolexical Syntax: A Theory of Noun Incorporation and Similar Phenomena. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 3:379–441.

———. 1994. “Reflexive Reference in West Greenlandic.” In Contemporary Linguistics, vol. 1, ed.

J. A. Goldsmith, S. Mufwene, B. Need, and D. Testen, pp. 137–160. Chicago: Department of Linguistics, University of Chicago.

———. 2003. A Grammar of Kalaallisut (West Greenlandic Inuttut). Munich: Lincom-Europa.

———. 2012. The Modular Architecture of Grammar. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics 132. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sadock, Jerrold M., and Carl Christian Olsen. 1976. “Phonological Processes across Word-Boundary in West Greenlandic.” In Papers on Eskimo and Aleut Linguistics, ed. E. P. Hamp, pp. 221–225. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Schuchardt, Hugo. 1895. Über den passiven Charakter des Transitivs in den kaukasischen Sprachen: Sitzungsberichte der kais. Akademie der Wissenschaften, phil.-hist. Klasse 133. Vienna: Akademie der Wissenschaften. [Facsimile edition, Munich: Lincom-Europa, 2012.]

Silverstein, Michael. 1976. “Hierarchy of Features and Ergativity.” In Grammatical Categories in Australian Languages, ed. R. M. W. Dixon, pp. 112–171. AIAS Linguistic Series 22. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Swadesh, Morris. 1951. Kleinschmidt Centennial III: Unaaliq and Proto-Eskimo. International Journal of American Linguistics, 17(2):66–70.

Woodbury, Anthony C. 1975. Ergativity of Grammatical Processes: A Study of Greenlandic Eskimo. Master’s thesis, University of Chicago.